Abstract

Background:

Prior research suggests that providing women newly diagnosed with breast cancer information during the gap between cancer diagnosis and their first surgeon consultation may support decision making. Our objective was to compare patients’ knowledge after the pre-consultation delivery of standard websites versus a web-based decision aid (DA).

Study Design:

We randomized women with stage 0-III breast cancer within an academic and community breast clinic to be emailed a link to selected standard websites (National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, Breastcancer.org,) versus the Health Dialog DA (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03116035). Patients seeking second opinions, diagnosed by excisional biopsy, or without an email address were ineligible. Pre-consultation knowledge was assessed using the Breast Cancer Surgery Decision Quality Instrument. We compared differences in knowledge using t-test.

Results

Median patient age was 59 years, 99% were white, and 65% a college degree or higher, with no differences in demographics between study arms. Knowledge was higher in patients who received the DA (median 80% vs 66% correct, p=0.01). DA patients were more likely to know that waiting a few weeks to make a treatment decision would not affect survival (72% versus 54%, p<0.01). Patients in both arms found the information helpful (median score 8/10).

Conclusion

Although patients found receipt of any pre-consultation information helpful, the DA resulted in improved knowledge over standard websites and effectively conveyed that there is time to make a breast cancer surgery decision. Decreasing the urgency patients feel may improve the quality of patient-surgeon interactions and lead to more informed decision-making.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Surgery, Decision-making, Knowledge, Decision aid, Internet

Precis

In this randomized trial, receipt of a web-based decision aid prior to the breast cancer surgical consultation resulted in improved knowledge when compared to receipt of selected, high-quality standard websites. Effectively conveying that there is time to make a decision for type of breast cancer surgery may be especially valuable, as this may decrease the urgency patients feel about making a decision.

INTRODUCTION

The majority of the 230,000 women diagnosed annually with early stage breast cancer must face the difficult and highly personal decision between breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy. It is essential that women feel empowered to actively participate in this decision, as playing an active role in decision making leads to less decisional regret, improved post-operative body image, and greater quality of life.1–3 A critical component to preparing patients to participate in decision making is providing them with information about their breast cancer and their surgical treatment options.4

Prior research suggests that information may be most beneficial to patients if they receive it during the informational gap between their cancer diagnosis and the first surgeon consultation.5,6 However, delivering information within this narrow window can be challenging. Online delivery is one way to address this challenge.7 In our multi-disciplinary breast program, we successfully developed an implementation strategy that facilitates the routine delivery of a web-based decision aid directly to patients in the informational gap prior to the first surgical consultation.8 Our pilot project demonstrated that this approach was feasible and highly acceptable to both patient and clinic stakeholders.

However, simply having a feasible strategy to deliver pre-consultation information to patients is insufficient to justify the routine use of this approach in practice. It is also critical to understand how delivering pre-consultation information to patients prior to the surgical consultation may influence outcomes relevant to patient decision making, such as knowledge. Additionally, we wanted to understand what format of web-based information may be most beneficial to patients. One option would be to share links to selected, high-quality websites that are available online, but that women may not find on their own.9 A second option would be a decision aid. Decision aids have proven efficacy at improving knowledge.10–12 However, many decision aids are commercially developed and, therefore, have a cost associated with their use. Understanding the relative benefits of pre-consultation delivery of a web-based decision aid versus other forms of web-based information would be highly beneficial in justifying the additional expense. The objective of this study was to compare patients’ knowledge of their surgical options after pre-consultation delivery of either a web-based decision aid or links to selected standard websites.

STUDY DESIGN

Study Design and Study Sample

This study was a randomized, blinded, prospective trial (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03116035). From 4/2014–6/2016, we randomized women newly diagnosed with stage 0-III breast cancer seen within an academic and community breast clinic to receive via email a link to either a web-based decision aid or selected, standard websites. Patients were eligible if they were female, had stage 0-III breast cancer, were 18 years of age or older, and were considering breast surgery within our breast program. We excluded patients who had recent contact with a breast surgeon, including those coming to our center for a second opinion, diagnosed by excisional biopsy, or with recurrent cancer. This exclusion was to minimize bias based on prior experience with or discussions about breast cancer, both of which could increase knowledge. Additional study specific exclusion criteria included the inability to read or comprehend health information in English (as the web-based materials were only available in English) or patients lacking decision-making capacity (e.g. dementia). Finally, patients had to have a valid email address.

The UW Human Subjects Committee approved the study protocol and all participants provided informed consent.

Intervention

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to receive either a decision aid or selected, standard websites. We used a decision aid developed collaboratively by the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation and Health Dialog (©Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making and Health Dialog).13,14 Originally created as a DVD, it was converted to a web-based platform based on user feedback requesting flexibility in mode of delivery. The web-based decision aid utilizes static, didactic information written for an 8th grade reading level, and video clinical vignettes to promote consideration of personal values and preferences. It includes modules for invasive cancer, non-invasive cancer, and reconstruction; patients had access to all modules. It has been used successfully in academic and community settings to increase knowledge and decrease decisional conflict.15–18

The standard websites were rated as high quality9 and were developed and supported by non-profit organizations. The included sites were: 1) breastcancer.org; 2) American Cancer Society-www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/index; and 3) National Cancer Institute-www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/breast. Each patient received links to all three sites.

Study Procedures and Measures

Usual clinic flow:

In the two clinics participating in this study, most patients undergo the diagnostic work-up which leads to their breast cancer diagnosis without meeting a surgeon. Patients are either called back for additional imaging after an abnormality is identified on their screening mammogram or referred directly to breast imaging by their primary care provider after the identification of a palpable mass. Usual clinic flow is for a nurse or nurse navigator to communicate the breast cancer diagnosis to patients via telephone when the results become available and promptly schedule a surgeon consultation. The median time between telephone call and surgeon consult in our study was 4 days (range 1–13).

Study flow:

Newly diagnosed breast cancer patients were screened for study eligibility by the breast center nurses. Eligible patients were offered the study by the nursing staff or breast cancer navigator via telephone, either at the time of diagnosis or when their appointment in the surgery clinic was made. Oral consent was obtained during this telephone call. The study coordinator then randomized patients using a randomization list generated at the beginning of the study by the study statistician; this was a block randomization with a block size of 6. The study coordinator emailed patients the assigned links and clinical staff was kept blinded to intervention assignment. The introduction email included suggestions of topics to review in both the standard and the decision aid websites (text available upon request).

Participants were administered a questionnaire in the clinic prior to their first surgical consultation upon arrival to the clinic. We selected this time point for measurement as we specifically wanted to assess the impact different types of web-based information had on patient outcomes prior to the surgical consultation, as this would identify the optimal format of information for future clinical and research use and assess the benefit of providing information during the gap between diagnosis and consultation. Our primary outcome for the study was patient knowledge, measured using the Breast Cancer Surgery Decision Quality Instrument.19 This instrument includes five items assessing knowledge on key concepts relevant to decision making for type of breast cancer surgery. The instrument is scored as a percentage of the number of questions answered correctly. Secondary outcomes included patients’ use (time spent reviewing web-based information) and perceived helpfulness of the information (measured by the single question “how helpful did you find the breast cancer websites that were emailed to you?”). Patient reported demographics included education history and baseline internet use. Following the surgeon consultation, a chart review was performed and information pertaining to tumor characteristics, clinical and pathologic disease staging, and surgical treatments received was abstracted. We collected zip code+4 for each participant and linked this to the Area Deprivation Index for a proxy of socioeconomic status; patients were grouped into quartiles using national cut-points.20,21

Analysis

Sample size calculation: In calculating our sample size, we estimated that the difference in knowledge score between the study arms would be 20%. We considered a Pearson Chi-square test for the two proportions, 0.50 and 0.70. Using the POWER procedure in SAS/STAT® software (version 9.3), we estimated the sample size to be n=124 per group based on type I error rate of 0.05 and power of 90%.

Summary descriptive statistics were used to confirm balance of patient characteristics between our randomization arms. Because of skewing of the data, median (rather than mean) values are presented. Patients who completed ≥3 knowledge questions were included in the final cohort for this analysis. The analysis followed an intention to treat approach, meaning patients were included in their study arm regardless of whether they actually reviewed the web-based information or not. The percent correct on the knowledge questions was calculated. Based on the distribution of the data, a t-test was used to compare overall knowledge as a continuous variable between the arms. Fisher’s exact tests (or chi-square where appropriate) were used to compare differences among proportions derived from categorical data, including responses to individual knowledge items. All p-values were 2-sided and considered statistically significant if p<0.05.

RESULTS

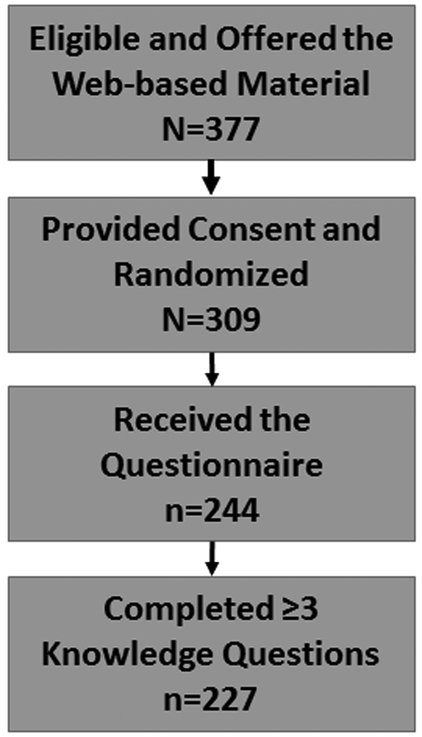

Figure 1 demonstrates the patient flow according to the CONSORT guidelines.22 Of the 377 potentially eligible patients, 309 consented to study participation (82%). Details of those patients declining study participation have been described in detail previously.8 Of the 309 consented patients, 244 received the questionnaire and 227 completed at least three of the knowledge questions; most patients (94%) completed all five knowledge questions. These patients comprise our study cohort.

Figure 1.

Study Flow

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic characteristics of our cohort. No statistical differences in patient characteristics between the study arms were observed at the time of the pre-consultation survey. Consistent with our breast center population, our patients were predominantly white (99%), educated (66% with at least a college degree), and affluent (53% in the highest socioeconomic quartile of the Area Deprivation Index).

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Participants

| Decision Aid N=116 |

Standard Websites N= 111 |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (median, range) | 61 (29-80) | 57 (27-78) | 0.16 | |

| Race | White/Non-Hispanic | 115 (99%) | 109 (98%) | 1.0 |

| Years of Education | High school or less | 9 (8%) | 14 (13%) | 0.29 |

| Some college | 25 (22%) | 31 (28%) | ||

| College degree | 47 (40%) | 39 (35%) | ||

| Graduate degree | 35 (30%) | 27 (24%) | ||

| Area Deprivation Index | Quartile 1 (lowest SES) | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 0.61 |

| Quartile 2 | 4 (4%) | 11 (11%) | ||

| Quartile 3 | 36 (33%) | 27 (26%) | ||

| Quartile 4 (highest SES) | 66 (61%) | 60 (59%) | ||

| Internet Experience | Less than once a week | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 0.38 |

| A couple of times a week | 9 (8%) | 6 (5%) | ||

| About once a day | 23 (20%) | 14 (13%) | ||

| Multiple times a day | 81 (70%) | 88 (79%) | ||

| Stage | Stage 0 | 20 (17%) | 16 (14%) | 0.79 |

| Stage 1 | 64 (55%) | 64 (58%) | ||

| Stage 2 | 30 (26%) | 28 (25%) | ||

| Stage 3 | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | ||

| Clinic Type | Academic | 71 (61%) | 56 (50%) | .10 |

| Community | 45 (39%) | 55 (50%) |

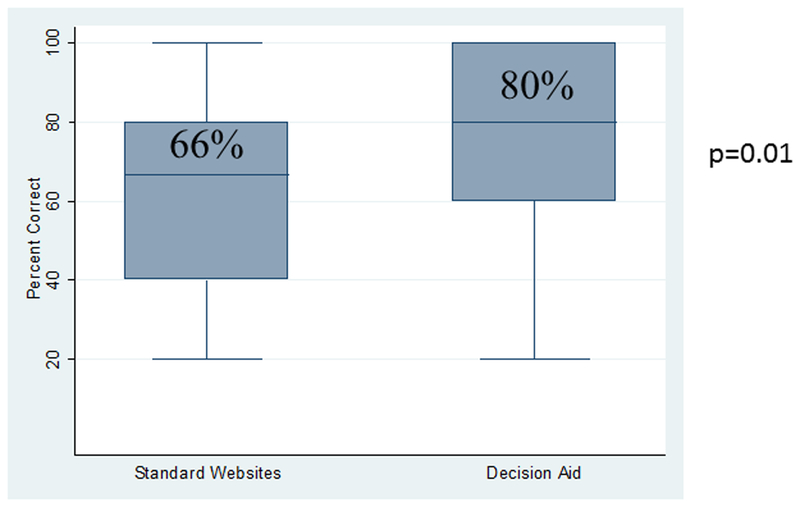

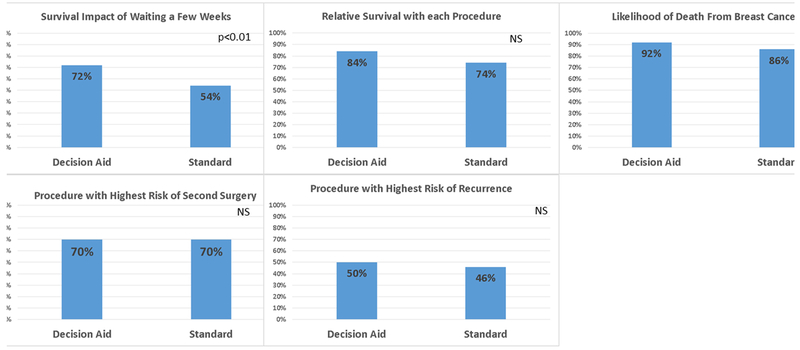

Patients who received the web-based decision aid demonstrated higher overall knowledge compared with patients who received the standard websites (median 80% vs 66%, p=0.01, Figure 2). Significant differences were observed on one of the individual questions comprising the knowledge scale (Figure 3), with patients who received the decision aid more likely to recognize that waiting a few weeks to make a decision for breast cancer surgery would not negatively impact survival (72% vs 54%, p<0.01).

Figure 2.

Overall knowledge score for patients who received the standard websites versus the decision aid. Median score and range are presented.

Figure 3.

Knowledge scores for individual items in Breast Cancer Surgery Decision Quality Instrument, by study arm.

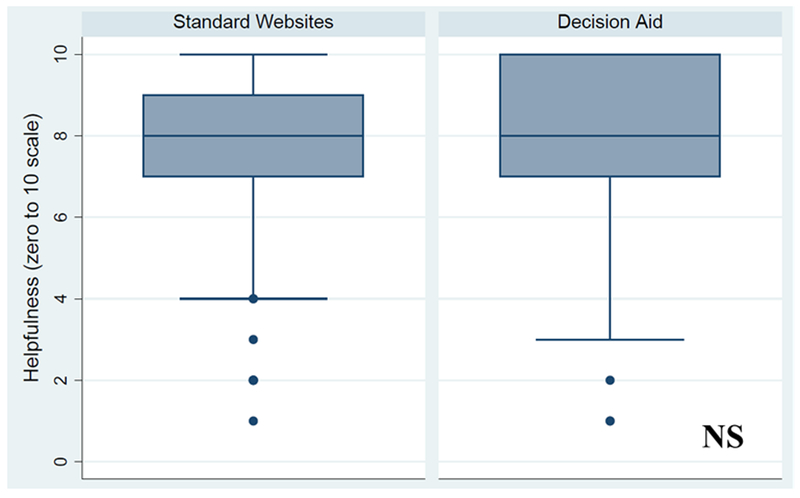

The majority of patients in both study arms spent some time reviewing the web-based material (85% reviewed the standard websites, 90% reviewed the web-based decision aid, p=0.3). Of the patients who reviewed the web-based material, 39% more than 60 minutes and 52% spent between 15–60 minutes; no differences between the study arm was observed (p=0.1). Patients in both study arms found the receipt of pre-consultation information to be very helpful (Figure 4). No patient demographic factors were associated with perceived helpfulness of the information. Overall, 74% of patients who received the standard websites and 72% of patients who received the decision aid underwent breast-conserving surgery (p=0.9). There was no difference in knowledge based on surgery received (p=0.9).

Figure 4.

Perceived helpfulness of web-based information, by study arm.

DISCUSSION

Breast cancer patients found the receipt of any pre-surgical consultation information highly beneficial. However, the pre-consultation delivery of a web-based decision aid resulted in improved knowledge when compared with selected, high-quality standard websites. The individual knowledge concept with the greatest difference between study arms was whether waiting a few weeks to make a decision regarding breast cancer surgery would have an impact on survival. Having an accurate understanding on this concept prior to the surgical consult may decrease some of the urgency patients feel around decision making. This may in-turn increase the quality of the surgeon-patient consultation, as patients may come to the consult more open to hearing the options and better prepared to consider those options within the context of their own personal preferences and values. This may ultimately lead to improved quality of patient decision making.

A second key finding is that there are some key concepts important for decision making for which patients still have limited knowledge, even after receipt of pre-consultation information. The best example is that less than half of women in either study arm correctly answered the question regarding likelihood of needing a second surgery. Although this gap may be addressed by the surgeon during the subsequent consultation, this suggests that there is room to improve the available information, even for a rigorously developed decision aid.

Our work represents a significant advance in the decision aid literature. Although prior randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that breast cancer surgery decision aids effectively support patient decision making,10,11,23,24 only a minority of the more than 200,000 women diagnosed annually ever receives one. 25–27 Barriers to implementation and sustained use of decision aids exist, including difficulties incorporating decision aids into clinic flow and limited clinic resources for administration.1,15–17,28–37 Most prior breast cancer surgery decision aid studies have assessed tools that are administered face-to-face in the clinic setting;11 while both patients and providers have reported these tools to be useful, this has not translated into routine use. Our study represents a significant advance as we tested the impact of a web-based decision aid on patient knowledge using an implementation strategy that could be readily translated into broad clinical practice with low use of clinic resources. Further, by delivering the decision aid directly to patients prior to the surgical consult, we address unmet needs of patients who are seeking accurate, high-quality information during this high-stress time.

Our study cohort represents a possible limitation to our study. The patient population at our breast center is largely white, educated, and fairly affluent. It is possible that findings would have been different had the study been conducted in a more diverse setting. However, prior studies using this decision aid have demonstrated that the greatest gains in knowledge were seen in patients with lower baseline education.18,24 Therefore, it is possible that even larger differences would have been observed had the study been conducted in a setting with greater educational diversity. Additionally, our patients had substantial experience with the internet at the time of diagnosis. Some concern exists that using a web-based approach may selectively exclude at-risk patient populations. However, internet use has increased steadily over the past decade; racial or ethnic minority patients, those with less education, and those with lower incomes have the fastest increases in adoption.38,39 Ongoing work by our research team is studying the use of this approach in minority and unserved populations. Next, patient preference for surgery is a critical outcome for this preference-sensitive decision. Although we collected data on surgical preference within our pre-consultation questionnaire, more than 40% of patients reported they were uncertain about their surgical preference; this makes it very difficult to provide any meaningful interpretation of the data. We have just completed additional data collection which provides more context for interpretation, and will report this within a separate manuscript. Finally, only 73% of patients that consented to the study completed at least three of the knowledge questions. Seventeen of these patients completed some portion of the survey. However, for the most of these patients (n=65), no survey data was available. This loss after randomization can be largely attributed to logistics of conducting this study within a busy breast program. In our study design, the medical assistant provided patients with the survey at the time of rooming, with the goal of survey completion prior to the surgeon entering the room. Although specific reasons for non-completion were not tracked, some patterns were observed: 1) the medical assistant not providing the survey in the context of an exceptionally busy clinic day, 2) the surgeon entering the room prior to the survey being competed, and 3) misplacement of the questionnaire from the clinic room after the consultation. As our loss rate between arms was similar, we think it is unlikely that this rate of loss after randomization would alter our study findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Women newly diagnosed with breast cancer found receipt of any web-based information prior to the surgical consultation to be helpful. Receipt of the decision aid resulted in improved knowledge when compared to receipt of selected, high-quality standard websites. Effectively conveying that there is time to make a decision for type of breast cancer surgery may be especially valuable, as this may decrease the urgency patients feel about making a decision. This may increase the quality of the patient-surgeon interaction and ultimately lead to higher quality, preference-aligned decision making around breast cancer surgery.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding: Research reported in this manuscript was funded in part through the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Scholar Program (NIH K12 HD055894), the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center (NIH/NCI P30 CA014520), and MT-DIRC Fellowship (R25CA171994).

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation: This paper was presented as an oral presentation at the Society of Surgical Oncology in Seattle, WA in March 2017.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mandelblatt J, Kreling B, Figeuriedo M, Feng S. What is the impact of shared decision making on treatment and outcomes for older women with breast cancer? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. October 20 2006;24(30):4908–4913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashraf AA, Colakoglu S, Nguyen JT, et al. Patient involvement in the decision-making process improves satisfaction and quality of life in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. The Journal of surgical research. September 2013;184(1):665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molenaar S, Sprangers MA, Rutgers EJ, et al. Decision support for patients with early-stage breast cancer: effects of an interactive breast cancer CDROM on treatment decision, satisfaction, and quality of life. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. March 15 2001;19(6):1676–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient education and counseling. March 2014;94(3):291–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hack TF, Degner LF, Parker PA. The communication goals and needs of cancer patients: a review. Psycho-oncology. October 2005;14(10):831–845; discussion 846–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belkora JK, Miller MF, Dougherty K, Gayer C, Golant M, Buzaglo JS. The need for decision and communication aids: a survey of breast cancer survivors. The Journal of community and supportive oncology. March 2015;13(3):104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman AS, Volk RJ, Saarimaki A, et al. Delivering patient decision aids on the Internet: definitions, theories, current evidence, and emerging research areas. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruce JG, Tucholka JL, Steffens NM, Mahoney JE, Neuman HB. Feasibility of providing web-based information to breast cancer patients prior to a surgical consult J Cancer Educ. 2017;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce JG, Tucholka JL, Steffens NM, Neuman HB. Quality of online information to support patient decision-making in breast cancer surgery. Journal of surgical oncology. November 2015;112(6):575–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trikalinos TA, Wieland LS, Adam GP, Zgodic A, Ntzani EE. Decision Aids for Cancer Screening and Treatment. Rockville (MD)2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waljee JF, Rogers MA, Alderman AK. Decision aids and breast cancer: do they influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. March 20 2007;25(9):1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ollila DW, Neuman HB, Sartor C, Carey LA, Klauber-Demore N. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy prior to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with large breast cancers. Am J Surg. September 2005;190(3):371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Medical care. August 1993;31(8):732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feibelmann S, Yang TS, Uzogara EE, Sepucha K. What does it take to have sustained use of decision aids? A programme evaluation for the Breast Cancer Initiative. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. March 2011;14 Suppl 1:85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silvia KA, Ozanne EM, Sepucha KR. Implementing breast cancer decision aids in community sites: barriers and resources. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. March 2008;11(1):46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silvia KA, Sepucha KR. Decision aids in routine practice: lessons from the breast cancer initiative. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. September 2006;9(3):255–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belkora JK, Volz S, Teng AE, Moore DH, Loth MK, Sepucha KR. Impact of decision aids in a sustained implementation at a breast care center. Patient education and counseling. February 2012;86(2):195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sepucha KR, Belkora JK, Chang Y, et al. Measuring decision quality: psychometric evaluation of a new instrument for breast cancer surgery. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2012;12:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969–1998. American journal of public health. July 2003;93(7):1137–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Annals of internal medicine. December 2 2014;161(11):765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Annals of internal medicine. June 01 2010;152(11):726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Durand MA, Carpenter L, Dolan H, et al. Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2014;9(4):e94670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, et al. “Many miles to go ...”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinha G Decision aids help patients but still are not widely used. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. July 2014;106(7). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeuner R, Frosch DL, Kuzemchak MD, Politi MC. Physicians’ perceptions of shared decision-making behaviours: a qualitative study demonstrating the continued chasm between aspirations and clinical practice. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. December 2015;18(6):2465–2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connor AM, Graham ID, Visser A. Implementing shared decision making in diverse health care systems: the role of patient decision aids. Patient education and counseling. June 2005;57(3):247–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang EH, Gross CP, Tilburt JC, et al. Shared decision making and use of decision AIDS for localized prostate cancer : perceptions from radiation oncologists and urologists. JAMA internal medicine. May 2015;175(5):792–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brace C, Schmocker S, Huang H, Victor JC, McLeod RS, Kennedy ED. Physicians’ Awareness and Attitudes Toward Decision Aids for Patients With Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. May 1 2010;28(13):2286–2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham ID, Logan J, O’Connor A, et al. A qualitative study of physicians’ perceptions of three decision aids. Patient education and counseling. July 2003;50(3):279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Self-reported use of shared decision-making among breast cancer specialists and perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing this approach. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. December 2004;7(4):338–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Legare F, Ratte S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient education and counseling. December 2008;73(3):526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Connor AM, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Flood AB. Modifying unwarranted variations in health care: shared decision making using patient decision aids. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Variation:VAR63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Donnell S, Cranney A, Jacobsen MJ, Graham ID, O’Connor AM, Tugwell P. Understanding and overcoming the barriers of implementing patient decision aids in clinical practice. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. April 2006;12(2):174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmes-Rovner M, Valade D, Orlowski C, Draus C, Nabozny-Valerio B, Keiser S. Implementing shared decision-making in routine practice: barriers and opportunities. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy. September 2000;3(3):182–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perrin A, Duggan M. “Americans’ Internet Access: 2000–2015.” Pew Research Center 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee CJ, Ramirez AS, Lewis N, Gray SW, Hornik RC. Looking beyond the Internet: examining socioeconomic inequalities in cancer information seeking among cancer patients. Health Commun. 2012;27(8):806–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]