Abstract

This study identifies factors that affect decisions people make regarding whether or not they want to receive life-sustaining treatment. It is an interpretive-descriptive study based on qualitative data from three focus groups (n=23), representing a diverse population in central Pennsylvania. Study sites included a suburban senior center serving a primarily white, middle class population; an urban senior center serving a frail, underserved, African-American population; and a breast cancer support group. The most important factors affecting whether participants wished to receive life-sustaining medical treatment were: prognosis; expected quality of life; burden to others; burden to oneself in terms of the medical condition and treatment; and effect on mental functioning and independence. Our findings contribute to the knowledge of the complex factors that influence how people make decisions about advance care planning and life-sustaining treatments. This understanding is critical if nurses are to translate the patient’s goals, values, and preferences into an actionable medical plan.

INTRODUCTION

Background

Advance care planning is a process of planning for future medical treatment in the event that a person cannot speak for him or herself. This is usually accomplished by completing an advance directive (AD), a document that outlines specific instructions for medical treatment and/or designates a proxy decision-maker. Despite widespread advocacy for their use (Silveira, Kim, & Langa, 2010), AD completion rates remain consistently low (McAuley, Buchanan, Travis, Wang, & Kim, 2006), and significant barriers exist to their implementation (Ditto & Hawkins, 2005). In recent years, questions have been raised about the effectiveness of ADs at achieving their intended outcomes (Fagerlin & Schneider, 2004), including concerns that ADs may not accurately reflect a person’s preferences for healthcare (Danis, Garrett, Harris, & Patrick, 1994; Hawkins, Ditto, Danks, & Smucker, 2005; Jordens, Little, Kerridge, & McPhee, 2005; Straton et al., 2004). Some have suggested that patients’ values are better predictors of preferences for end-of-life medical treatment, and there is some evidence that a values-based advance care planning document may be more acceptable than a standard living will for some people (Winter, 2013).

In prior work, we have shown that a computer-based decision aid is effective at eliciting individuals’ goals and values and translating these into instructional directives that can be implemented by health care providers (Green & Levi, 2009). The key component of the decision aid involves application of multi-attribute utility theory, a technique developed to break down complex decisions into a series of simpler ones to identify and prioritize “attributes” of decisions. The “attributes” can be thought of as the factors that influence a person to decide in a certain way. This present paper looks back at the process by which those attributes were identified and, subsequently, integrated into a systematic approach for clarifying a person’s wishes. These findings may be relevant to others who are interested in developing other advance care planning interventions.

THE STUDY

Aim

In developing the algorithm for our decision aid, it was important for us to understand which factors influence people’s decisions to receive (or not receive) life-sustaining medical treatment. This information was used in developing an interactive activity within the decision aid that has individuals rank and rate the relative importance of various attributes. To identify beliefs and preferences about such factors, we conducted a series of focus group interviews and report those findings here.

Design

This was an interpretive descriptive study based on qualitative data obtained from focus groups.

Participants

Participants for this study were recruited from three separate locations: (1) a suburban senior center serving a primarily white, elderly, middle class population; (2) an urban senior center serving a frail, underserved, primarily African American population; and (3) a support group whose members had undergone treatment for breast cancer. Using conventional focus group methodology (Krueger & Casey, 2009), we kept the groups small enough to allow everyone to speak, but large enough to capture a range of views and experiences. Members of each group were somewhat homogeneous with respect to race, ethnicity, language, literacy level, and income.

Data Collection

Three focus groups were conducted, each lasting 60 to 90 minutes. These were held in private rooms at an academic medical center and at two senior centers. One of the authors, an experienced focus group facilitator (CD), led the semi-structured sessions using prompts developed by our study team. Participants initially were asked whether they had to make a “really big” decision about their own health lately and/or whether they had to make a decision for somebody else. Probing questions included whether they knew the other person’s wishes and whether the decisions made were different from those wishes. Participants were asked if they had thought about advance care planning in relation to themselves, whether they had a living will, and if so, what factors influenced their decisions to receive or not receive medical treatment at the end of life. The prompts triggered memories and encouraged open discussion of their own experiences. The focus group discussions were audio-taped, transcribed, and reviewed for accuracy by the facilitator before field notes were added to the transcripts.

Ethical Considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to starting the focus group. Due to the sensitive nature of the discussion, options for follow-up with primary care providers or members of a crisis intervention team were made available in the event that a participant experienced undue emotional distress. The Institutional Review Board from our institution approved the procedures used in this study.

Data Analysis and Rigor

All discussions were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Typed and taped interviews were then compared and the transcripts cleaned as necessary. The content of the interview transcripts were then analyzed using the following process to identify themes (Kidd & Parshall, 2000). First, two of the research team members (MW and CD) independently conducted a line-by-line review of each transcript, synthesizing codes that related to the study question, “What factors affect an individual’s decision to receive (or not receive) medical treatment?”

Through an iterative process, the reviewers independently coded the complete transcripts from each focus group and then compared identified codes. Differences in coding were reconciled by (1) discussion about the meaning of the code until agreement was reached or (2) creation of a new code that captured the content of the statement.

Codes were then collapsed into thematic categories using the same process. At this point, a research team member who had not seen the codes or thematic categories (BL) reviewed the identified codes and thematic categories as a validity check. Finally, thematic categories were presented to the entire research team, and a conceptual model for advance care planning developed. Within groups and across groups analyses were completed. Because there was no variation between the three groups, aside from linguistic characteristics of the various constituencies, the results are reported across groups.

The credibility of our interpretation of the results was enhanced by the different perspectives and interests of our research team (Patton, 2002), which included physician researchers who were content experts (MG and BL), and experienced qualitative researchers (JS and CD). In our team discussions, we considered alternative explanations and themes, and looked for negative cases that might challenge our assumptions (Patton, 2002).

RESULTS

Twenty-three individuals participated: 9 from the suburban senior center, 7 from the urban senior center, and 7 from the breast cancer support group. All participants were English speaking and lived in central Pennsylvania. Mean age was 74 years (range 54–87), and 15 of 23 (65%) participants were female. Full demographic information is available for only 14 participants: 7 of 14 (50%) were African American; 9 of 14 (64%) were educated through high school or less; and 4/12 (33%) previously completed an advance directive.

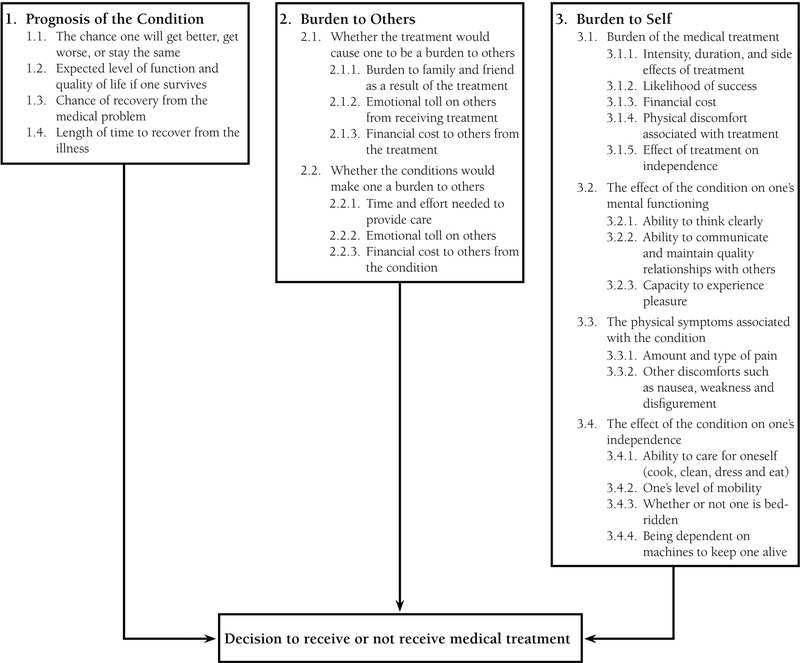

Three conceptual categories were identified that describe participants’ decisions to receive (or not receive) medical treatment: 1) Prognosis; 2) Burden to others; 3) Burden to self. Within these categories, 10 separate themes with additional subthemes were captured (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Categories and Themes

Prognosis.

The prognosis of the medical condition was the first overarching category identified. This included the likelihood that the person would get better, get worse, or stay the same, and encompassed the expected level of function and quality of life if the person survived, length of time to recover, and life expectancy following treatment. Representative comments included:

“If this is temporary, I’m for it. But if I knew I was never going to come out of it, then I don’t want that. I want to know the worst and best-case scenarios.”

“I would definitely want to know what my chances of survival are …, am I going to be a vegetable, am I going to walk again, am I going to be in a wheelchair for the rest of my life?”

Burden to Others.

The second category was whether the treatment or condition would cause the person to become a burden to others, particularly family and friends. This included the emotional toll and financial cost to others resulting from the treatment or condition. Representative comments included:

“I have a tendency to think more of my family members than myself and I will take that into consideration.”

“I’d be more hesitant to do something if it was going to be more of a disadvantage to my family than an advantage to myself.”

“If I thought I was going to remain in a vegetative state there’s no way I would want to be kept laying there for years, even years, even months. I think it’s a terrible hardship on your family. I’d still go into a [nursing] home. I don’t want to burden my child.”

Another felt that being alive but “mentally challenged would be ok” if she remained useful. “If I could still rock babies – as long as I’m doing something useful.” She drew the line if she were to “lose all function, [be] chair-bound, or burden to family.” Participants were in agreement about the burden to family if life is reduced to mere existence.

“Maybe if they could keep me alive and I wouldn’t be a burden to somebody. I wouldn’t want to be a burden.”

Participants expressed concerns about the emotional toll that the family experiences. This included the emotional burden associated with making end-of-life care decisions for a loved one. For one participant, the main reason for advance care planning was, “So that family will not have burden of decision.”

“I do know that it is more painful for the person trying to make these decisions. Sometimes our family members go through more than we do. I do want my husband when he has to make these decisions [to be] in peace when he makes them.”

“I put it in my will so my kids won’t have to make that decision.”

For most participants, “burden to family” was described in terms of a life of dependence on others. One participant, a single mother, provided a contrasting view: staying alive for her children would override the burden and uncertainty of life-sustaining treatment:

“My kids came over to the house together and were talking about this … and the spokesman said, mama you all we got and we’ll do anything it takes to keep you alive and they agreed to it.”

Finances were mentioned repeatedly. A representative comment was:

“I’d like to know, if you can know this, what position I’m putting my family in. What kind of care would be required both in terms of care and finances.”

Burden to Self.

The third category, burden to self, encompasses both the medical condition and its treatment. This includes the effect of the medical condition on a person’s physical and mental functioning, particularly as it affects the ability to think clearly, to communicate, and to maintain quality relationships with others, especially family. The category also includes the duration, intensity, and side effects of the treatment as well as the likelihood of success and its cost. Participants also mentioned the physical discomfort associated with treatment (such as pain) and the effect of treatment on a person’s independence.

“I’ve often remarked that yes it would be nice to live to be 100 as long as I had my wits about me and my health but not if I was just so almost like a vegetable. That’s not my way of wanting to live to be a hundred.”

“If you have any type of handicap, as long as you have your mind you can … there’s wheelchairs, there’s all kinds of help, you can get around, you can read. If I can’t read, I might as well be dead. Not being aware of what’s going on has to be the worse.”

“If you’re mentally incapacitated, life is almost zilch. I mean I’m going to do everything I can to stay healthy and stay alive and be vibrant and useful but if that’s not what God has planned for me then that’s OK too … Once a person has outlived his or her usefulness, then I think it’s time to move on.”

One participant offered a contrasting view:

“Now if I could just … think and still have my faith, that’s something different. I believe every person’s life has value to their last dying breath. I also believe that so in that, there’s a catch-22.”

The physical symptoms associated with a medical condition include the amount and type of pain, nausea, weakness and disfigurement. Of these, pain was mentioned most frequently. One participant stated, “I’d want to know how much pain I would be in. Then, how much medication I would be on in order to take care of that pain which would then put me in what kind of a state.” Also, the effect of the medical condition on a person’s independence was a prime consideration and encompassed the ability to care for oneself and maintain a home, and the overall level of mobility, whether or not bed-ridden or dependent on machines to stay alive.

“I don’t want to be kept alive, I don’t want to be fed artificially. I don’t think that’s good for anybody. I don’t think it’s good for the family, I don’t think it’s good for the person. I just think it’s horrible. We give our animals more respect than that.”

“I could be happy, not as happy, but I could talk myself into being in a wheelchair for the rest of my life if I could still see my friends and go to church and be with my family. There are ways of doing that. I might have to move back to … be with my family. I could certainly still contribute to society from a wheelchair.”

“If somebody were to tell me that I could not ever again get behind the wheel and drive, I would say I don’t want [life-saving medical treatment].”

Self-defined quality of life was overwhelmingly a prime consideration:

“Yes. I wouldn’t want to have to take a medicine just to keep me cognizant. To do what? Just sit there?”

One participant spoke of time and effort care burden as being: “so dilapidated and handicapped that I don’t know what’s going on or I’m such a burden to everybody around me, I can’t participate in life.” Several participants framed their responses in terms of whether the intervention was temporary or not—mechanical ventilation and feeding tubes, for example, were acceptable, but only for a short duration. Others looked to longer-term medical outcomes: “If I’m not going to be functional, then I’m out of here.”

DISCUSSION

Several key points emerged from our study. First, multiple factors affect the decisions people make about whether or not to receive medical treatment at the end of life. While people are motivated by self-interest (avoiding their own pain and suffering), the desire to not burden family members is a key, and perhaps larger, concern. This includes the expense of life sustaining treatment; people do not want to jeopardize the financial health of their family members.

Second, people define “quality of life” in a wide variety of ways. Some people would be content with major debilities while others would not want to live if they were unable participate in independent activities.

A striking observation in our study was that while various treatment decisions were discussed by the participants, the decisions to receive or not receive specific medical treatment were not influenced by the specific intervention as much as by the prognosis and the burden to self and others. The one exception is that participants made strong statements about “breathing machines.” The facilitator asked probing questions about multiple interventions, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, nutrition and hydration (feeding tubes, intravenous fluids), medication (chemotherapy), renal dialysis, and mechanical ventilation, but mechanical ventilation elicited the strongest responses: “I said no to ventilator.” Participants did not make a distinction between decisions to initiate/prohibit clinical interventions versus decisions to discontinue potentially life-sustaining treatments.

Decisions to receive life-sustaining treatment are complex; knowing how to facilitate this process requires that nurses and other clinicians do more than understand a person’s disease. These discussions often occur at the bedside, where nurses play a key role in helping with the decision-making, so it is important for these practitioners to be familiar with the patient’s values and goals.

We discovered that anecdotes and personal experiences powerfully influence people’s desires, perhaps even more so that facts, probabilities, and dispassionate information. This has important implications for how nurses can engage people in advance care planning discussions. Key influencing factors that shaped the focus group participants’ views about specific interventions were predominantly their own prior experiences with family and friends. Knowledge of mechanical ventilation was typically gained through some previous observation: “They said he [a friend] could never get any better and he would always have to be on life support.” Participants also mentioned highly publicized news events.

Advance care planning is difficult in part because advance directives typically focus on the decision (I want or I don’t want xxx), rather than the deliberation (what’s important to me is xxx). ADs have performed poorly in the United States since their introduction (Winter, Parks, & Diamond, 2010) for a number of reasons: preferences may change over time as health status changes (Fried et al., 2006); sicker patients may view life sustaining aggressive treatment more favorably (Winter & Parker, 2007); terminology used in living wills may not be clear (Sahm, Will, & Hommel, 2005); and the various AD forms themselves may influence the results (Nishimura et al., 2007). This needs to change if ADs are to be useful. In fact, Winter (Winter, 2013) recently demonstrated that values are useful guides for understanding end-of-life treatment preferences and identified the following issues as particularly relevant: dignity, pain management, reluctance to burden others, religiosity, desire for longevity, and following family wishes.

Nurses are at the forefront of helping patients and their loved ones carry out end-of-life decision-making, often in an atmosphere of crisis (Scherer, Jezewski, Graves, Wu, & Bu, 2006). For some, this is a difficult and awkward situation, but by becoming informed and making oneself available for discussions, nurses can help make a painful process less so. Inviting patients to discuss their concerns, providing examples of different therapies, and avoiding judgment are all strategies that can promote ACP.

The use of focus groups for understanding aspects of advance care planning is not new. For example, previous researchers have used this methodology to ask patients about their general preferences regarding life-sustaining treatment, and about their specific preferences with respect to hospitalization and medical interventions such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and artificial ventilation under various clinical circumstances (Danis et al., 1991). Others have used focus groups to explore participants’ views on the acceptability and structure of ACP discussions in clinical practice (Barnes, Jones, Tookman, & King, 2007), barriers to their implementation (Schickedanz et al., 2009), and general perspectives of end-of-life care planning and decision-making (Waters, 2001). One recent study (Schaffer, Keenan, Zwirchitz, & Tierschel, 2012) used focus groups to examine the viewpoints of residents of assisted living facilities, their families, and staff members to study the organizational culture and societal attitudes toward death and dying. Another recent study (Ko & Nelson-Becker, 2013) used focus groups to understand the perspectives, needs and concerns of older homeless adults living in a transitional housing facility. Our focus group study adds to this literature by examining the underlying factors that influence individuals’ decisions to accept, or not accept, life sustaining care.

Like all studies, this research has several limitations including a small sample size, lack of geographic variation, and exclusive reliance on focus group methodology for data collection. All these factors may limit generalizability of our findings. Nevertheless, this study offers insights into how people think about end-of-life decisions and their reasoning when considering treatment options.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the findings from our focus group study of a diverse sample of middle-aged and older adults in central Pennsylvania demonstrate that there are many varied reasons that people say they would accept, or not accept life-sustaining medical treatment at the end of life. To the extent that our findings are generalizable, the implication of this is that there will not be a “one size fits all” approach to advance care planning. As we learn more about patterns of decision making, nursing interventions to promote advance care planning will need to be tailored to the values and needs of disparate populations.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study was funded by a grant from the NIH, National Institute of Nursing Research (1R21NR008539). The study sponsor was not involved in this study.

REFERENCES

- Barnes K, Jones L, Tookman A, & King M (2007). Acceptability of an advance care planning interview schedule: a focus group study. Palliative Medicine, 21(1), 23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M, Garrett J, Harris R, & Patrick DL (1994). Stability of choices about life-sustaining treatments. Annals of Internal Medicine, 120(7), 567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M, Southerland LI, Garrett JM, Smith JL, Hielema F, Pickard CG, … Patrick DL (1991). A prospective study of advance directives for life-sustaining care. New England Journal of Medicine, 324(13), 882–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditto PH, & Hawkins NA (2005). Advance directives and cancer decision making near the end of life. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 24(4 Suppl), S63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerlin A, & Schneider CE (2004). Enough. The failure of the living will. The Hastings Center Report, 34(2), 30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, Van Ness PH, Towle VR, O’Leary JR, & Dubin JA (2006). Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Archive of Internal Medicine, 166(8), 890–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, & Levi BH (2009). Development of an interactive computer program for advance care planning. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 12(1), 60–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins NA, Ditto PH, Danks JH, & Smucker WD (2005). Micromanaging death: process preferences, values, and goals in end-of-life medical decision making. The Gerontologist, 45(1), 107–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordens C, Little M, Kerridge I, & McPhee J (2005). From advance directives to advance care planning: current legal status, ethical rationales and a new research agenda. Internal Medicine Journal, 35(9), 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd PS, & Parshall MB (2000). Getting the focus and the group: enhancing analytical rigor in focus group research. Qualitative Health Research, 10(3), 293–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko E, & Nelson-Becker H (2013). Does End-of-Life Decision Making Matter? Perspectives of the Older Homeless Adults. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RA, & Casey MA (2009). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- McAuley WJ, Buchanan RJ, Travis SS, Wang S, & Kim M (2006). Recent trends in advance directives at nursing home admission and one year after admission. The Gerontologist, 46(3), 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura A, Mueller PS, Evenson LK, Downer LL, Bowron CT, Thieke MP, … Crowley ME (2007). Patients who complete advance directives and what they prefer. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic, 82(12), 1480–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods (3rd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sahm S, Will R, & Hommel G (2005). Would they follow what has been laid down? Cancer patients’ and healthy controls’ views on adherence to advance directives compared to medical staff. Medicine, Health Care, and Philosophy, 8(3), 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer MA, Keenan K, Zwirchitz F, & Tierschel L (2012). End-of-Life Discussion in Assisted Living Facilities. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 14(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer Y, Jezewski MA, Graves B, Wu YW, & Bu X (2006). Advance directives and end-of-life decision making: survey of critical care nurses’ knowledge, attitude, and experience. Critical Care Nurse, 26(4), 30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, Knight SJ, Williams BA, & Sudore RL (2009). A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 57(1), 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira MJ, Kim SY, & Langa KM (2010). Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. The New England Journal of Medicine, 362(13), 1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straton JB, Wang NY, Meoni LA, Ford DE, Klag MJ, Casarett D, & Gallo JJ (2004). Physical functioning, depression, and preferences for treatment at the end of life: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 52(4), 577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters CM (2001). Understanding and supporting African Americans’ perspectives of end-of-life care planning and decision making. Qualitative Health Research, 11(3), 385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter L (2013). Patient values and preferences for end-of-life treatments: are values better predictors than a living will? Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16(4), 362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter L, Parks SM, & Diamond JJ (2010). Ask a different question, get a different answer: why living wills are poor guides to care preferences at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 13(5), 567–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]