Abstract

Background

1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) can reveal changes in brain biochemistry in vivo in humans and has been applied to late onset Alzheimer disease (AD). Carriers of mutations for autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease (ADAD) may show changes in levels of metabolites prior to the onset of clinical symptoms.

Methods

Proton MR spectra were acquired at 1.5T for 16 cognitively asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic mutation carriers (CDR < 1) and 11 non-carriers as part of a comprehensive cross-sectional study of preclinical ADAD. Levels of N-acetyl-aspartate+N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate (NAA), glutamate/glutamine (Glx) and creatine/phosphocreate (Cr), choline (Cho), and myo-inositol (mI) in left and right anterior cingulate and midline posterior cingulate and precuneus were compared between mutation carriers (MCs) and non-carriers (NCs) using multivariate analysis of variance with age as a covariate. Among MCs, correlations between metabolite levels and time until expected age of dementia diagnosis were calculated.

Results

MCs had significantly lower levels of NAA and Glx in the left pregenual anterior cingulate cortex, and lower levels of NAA and higher levels of mI and Cho in the precuneus compared to NCs. Increased levels of mI were seen in these regions in association with increased proximity to expected age of dementia onset.

Conclusions

MRS shows effects of ADAD similar to those seen in late onset AD even during the preclinical period including lower levels of NAA and higher levels of mI. These indices of neuronal and glial dysfunction might serve as surrogate outcome measures in prevention studies of putative disease-modifying agents.

Keywords: autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, presymptomatic, biomarker

Introduction

The neurodegenerative processes characteristic of Alzheimer disease (AD) predate the development of clinical dementia by decades (Bateman et al., 2012; Katzman et al., 1988). These changes include neuronal loss and the development of amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and associated gliosis (Scheltens et al., 2016). Persons in this presymptomatic stage provide the opportunity to prevent the symptomatic disease and the development of therapeutics that target this early neurodegeneration requires biomarkers that accurately predict the development and progression of clinical dementia. A number of biomarkers have been proposed to behave in a predictable fashion in AD including beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptide and hyperphosphorylated tau protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a specific pattern of hypometabolism on FDG-PET, identification of amyloid pathology using amyloid PET and hippocampal atrophy on structural MRI (Jack et al., 2010, 2011, 2013). These biomarker changes have also been identified in ADAD (Bateman et al., 2012; Ringman et al., 2008). These biomarkers, however, have limitations including accessibility in clinical practice, standardization, and the definition of cut-off thresholds for reliable identification of AD pathology.

1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) provides a way to study brain biochemical processes in vivo. In patients with dementia due to AD, 1H MRS has consistently shown decreases in N-acetylaspartate (NAA), which is produced in neuronal mitochondria and found predominantly in neurons, as well as increased levels of myoinositol (mI), a glial cell marker (Wang et al., 2015; Zhang, Song, Bartha, Beyea, & Arcy, 2014). Alterations in the levels of these metabolites have been shown to correlate with the neuropathological findings in AD (Kejal Kantarci et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2014) and to also correlate with performance on tests of cognition (Frederick et al., 2004). Changes in NAA/Cr in the occipital cortex (Modrego, Fayed, & Pina, 2005; Modrego, Fayed, & Sarasa, 2011), posteromedial parietal lobe (including the posterior cingulate gyrus and precuneus) (Modrego et al., 2011), and left paratrigonal white matter (Metastasio et al., 2006) as well as mI/Cr in the right parietal lobe (Targosz-gajniak et al., 2013) also appear to predict cognitive decline and conversion to dementia in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Results of 1H MRS studies of other metabolites including Cho (representing phosphatidyl choline and other membrane precursors, a marker of membrane turnover), Cr (representing creatine and phosphocreatine) and Glx (representing glutamate and glutamine) have been less consistent (Zhang et al., 2014). Prior 1H MRS studies in AD have been limited in the preclinical stage of the disease due to the difficulty of identifying appropriate subjects.

Autosomal dominant AD is caused by mutations in the PSEN1, APP, and PSEN2 genes with symptoms typically starting at a relatively young age. This population represents an opportunity to study metabolite levels in preclinical AD since carriers of the mutation develop AD with essentially 100% penetrance. A single study of 7 such ADAD mutation carriers (MCs) previously showed lower ratios of NAA/Cr and NAA/mI compared to non-carriers (NCs) in a single midline voxel containing the posterior cingulate (Godbolt et al., 2006). In the present study we attempted to identify if these changes are seen more broadly and at what stage in ADAD.

Methods

Subjects were participants in a comprehensive study of preclinical and manifest ADAD at a tertiary dementia referral center. The study was approved by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Human Subjects Committee and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All subjects were first-degree relatives of someone known to carry a pathogenic mutation in the PSEN1, APP, or PSEN2 genes, placing them at 50% risk for inheriting such a mutation and therefore developing ADAD. Genetic testing for the relevant mutation was performed as part of this study but subjects were not informed of the results. Revealing clinical genetic testing was offered outside of the research protocol for interested subjects. Extraction of DNA and genotyping of apolipoprotein E (APOE) were performed using standard techniques. APOE SNP genotyping was carried out by real-time PCR on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Real Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using Taqman SNP Genotyping Assays (#C3084793_20 and C904973_10 for rs429358 and rs7412, respectively). The SDS version 2.3 software was used to analyze the raw data and to call the genotype. The presence or absence of the specific mutation each subject was known to be at-risk for were assessed using standard Sanger sequencing, according to published protocols and primers.

The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) was performed with an unrelated informant (Morris, 1997). The CDR is a structured interview with input from both the subject and an informant who knows the subject well. In the CDR, asymptomatic persons are rated 0, and persons with questionable cognitive impairment are rated 0.5. Scores of 1, 2, and 3 represent mild, moderate, and severe stages of dementia, respectively. Subjects with clinical dementia (CDR of 1 or higher) were excluded from the analysis.

Each subject’s age in relation to their estimated age of dementia diagnosis was calculated. As the age of onset of symptoms is fairly consistent within a family and mutation but more variable between families (Ryman et al., 2014), an “adjusted age” can be calculated that estimates how many years from disease manifestation a given subject is (Ryman et al., 2014). In our experience, we have found that the age of clinical diagnosis of dementia is a more reproducible measure and therefore we calculated an adjusted age for each subject as his or her chronological age minus the median age of dementia diagnosis in his or her family.

Whole-brain structural MRI and water-suppressed 1H MRS were acquired at 1.5 T on a Siemens Sonata scanner. MRS was acquired in 2D magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) configuration with a point-resolved spectroscopy sequence (PRESS) with repetition-time (TR) of 1500 ms, echo-time (TE) of 30 ms, and 8 excitations. Two 4×4 MRSI arrays or “slabs” (i.e., PRESS excitation volumes within 16×16 phase-encoding grids) were acquired, each with in-plane voxel resolution of 11×11 mm2. The first slab16 was 9 mm thick and axial-oblique, oriented parallel to the genu-splenium plane. It was positioned dorsoventrally symmetrically about the genu of the corpus callosum and left-right symmetrically astride the longitudinal fissure with the posterior slab edge abutting the genual rostrum. Posterior voxels within the slab sampled left and right pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (LpAC and RpAC, respectively). The second slab (O’Neill, Tobias, Hudkins, & London, 2015) was 12 mm thick and sagitally oriented. It was positioned left-right symmetrically astride the longitudinal fissure. The rear edge of the slab was aligned parallel to the parieto-occipital sulcus; the inferior edge was parallel or tangent to the dorsal margin of the isthmus or splenium of the corpus callosum. Thus, the slab sampled midline posterior cingulate (mPCG; inferior voxels) and midline precuneus (mPC; superior voxels). MR spectra were fit automatically with the LCModel commercial software package (Provencher, 2001) yielding levels of NAA, Glx, Cr, Cho, and mI, referenced to unsuppressed water and expressed in institutional units (IU). Water-reference was preferred to referencing metabolite ratios to Cr due to certain weaknesses of the latter (Alger, 2011). Cr measurement can be limited by overlap with neighboring signals (especially Cho). The Cr signal is a much smaller than the water signal and is thus more sensitive to noise. Also, accumulating evidence that Cr varies across the brain, with age, and with disease has gradually undermined earlier faith in Cr as a constant standard. After segregation of the whole brain MRI into gray matter, white matter, and CSF binary masks (Shattuck, Sandor-Leahy, Schaper, Rottenberg, & Leahy, 2001) the MRSI Voxel Picker (MVP) package (Seese et al., 2011) was used to compute the volume percent of gray matter, white matter, and CSF in each voxel and correct the LCModel-derived levels of each metabolite for voxel CSF content. Spectra not meeting quality control criteria (linewidth ≤ 0.1 ppm and signal-to-noise ratio ≥ 3) were rejected. Additionally, within spectra, individual metabolite peaks were rejected that were not considered reliable by LCModel (standard deviation of metabolite signal > 20%).

Characteristics of the study population were compared using two-sided Fisher exact tests for nominal variables and Student’s t-test for quantitative variables. For comparison between groups and regions of interest, a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) with age as a covariate was performed for each region of interest across five metabolites (NAA, Glx, Cr, Cho, and mI). If the overall MANCOVA for a region showed a significant effect of diagnosis, protected post-hoc ANCOVA testing was performed for individual metabolites.

Within the MC group, we determined whether there was a correlation between metabolite levels and time until expected onset of dementia using a Spearman correlation. To correct for multiple comparisons a Holm-Bonferroni test was applied. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 3.3.1.

Results

The study population was comprised of 16 preclinical (CDR < 1) MCs and 11 NC controls with MRS data acquisition as part of the above study protocol. Data were missing from 3 MCs for the LpAC and RpAC, and 3 different MCs for mPCG and mPC; data were missing from 1 NC for LpAC, 2 NCs for RpAC, and 3 NCs for mPCG and mPC. These subjects were excluded from the analysis of the relevant voxels. Demographic information for the study participants is found in Table 1. The majority of MCs carried a mutation in PSEN1 (n=13) while the remaining 3 had mutations in APP. Among MCs, 11 had CDR of 0 and 5 had CDR of 0.5. Among NCs, 2 subjects were blindly rated as having a CDR score of 0.5 but considering their ages (37 and 39), the etiology was considered unlikely to represent early AD. There was a significant difference in mean age between MCs (33, range 19–43) and NCs (40, range 28–59) (p=0.03). Study participants were predominantly female (81% and 73% in MCs and NCs, respectively; not significant). Most participants were APOE ε3/ε3 or ε2/ε3 genotype, with 2 in each group being ε3/ε4 (13% and 18%, respectively; not significant). The mean time until expected onset of dementia in MCs was 12.3 years.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| MC (n=16) | NC (n=11) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Female gender (%) | 13 (81%) | 8 (73%) |

|

| ||

| Mean age (s.d.) | 32.6 (7.0) | 40.1* (10.0) |

|

| ||

| Mean years until median age of dementia onset in the family (s.d.) | 12.3 (8.7) | 4.64 (13.4) |

|

| ||

| Family mutation (%) | ||

| PSEN1 | 13 (81%, 11 A431E, 2 L235V) | 8 (80%, 7 A431E, 2 L235V) |

| APP | 3 (19%, V717I) | 2 (20%, V717I) |

|

| ||

| APOE genotype (%) | ||

| 3/3 | 11 (69%) | 8 (73%) |

| 3/4 | 2 (13%) | 2 (18%) |

| 2/3 | 3 (19%) | 1 (9%) |

|

| ||

| CDR = 0 | 11 (69%) | 9 (82%) |

| CDR = 0.5 | 5 (31%) | 2 (18%) |

p=0.03

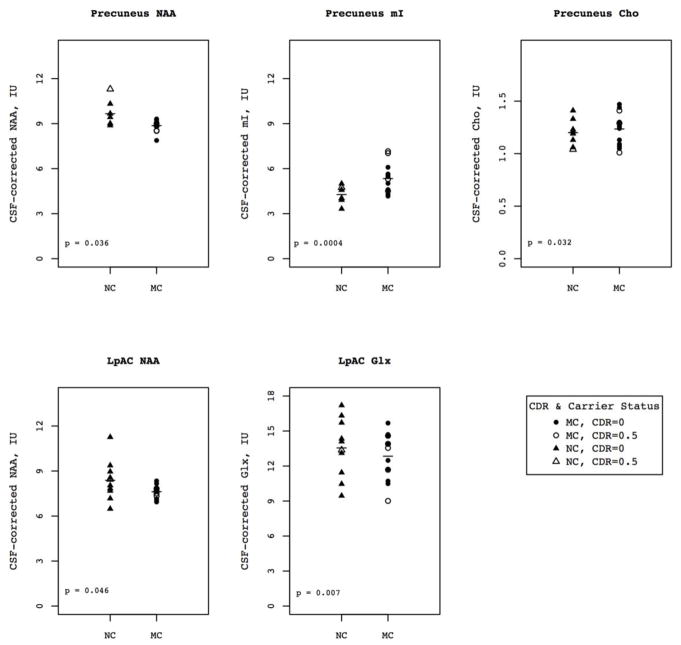

Results of MANCOVA analysis for the five metabolites of interest by voxel with age as a covariate showed a significant effect of mutation status in the LpAC (F=3.067, p = 0.040) and mPC (F=4.400, p=0.013) (Table 3). There was no effect of diagnosis in the RpAC or mPCG. Post-hoc protected ANCOVA with age as a covariate in the LpAC showed that MCs had lower NAA than NCs (7.61 vs 8.38, p=0.04) and lower Glx (12.84 vs 13.55, p=0.007). In the mPC, MCs had higher mI compared to NCs (5.3 vs 4.2, p=0.0004), higher Cho (1.23 vs 1.20, p=0.03) and lower NAA (8.86 vs 9.66, p=0.04).

Table 3.

1H-MRS mean metabolite values by voxel in MCs and NCs.

| MC | MC | NC | NC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel | Metabolite | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p |

| LpAC | Cho | 1.66 | 0.21 | 1.84 | 0.34 | 0.174 |

| Cr | 5.13 | 0.50 | 5.37 | 1.12 | 0.480 | |

| mI | 4.63 | 0.66 | 4.72 | 0.89 | 0.802 | |

| NAA | 7.62 | 0.42 | 8.38 | 1.32 | 0.046* | |

| Glx | 12.84 | 1.99 | 13.55 | 2.53 | 0.007* | |

| RpAC | Cho | 1.66 | 0.34 | 1.75 | 0.20 | 0.833 |

| Cr | 5.71 | 0.91 | 5.59 | 1.28 | 0.632 | |

| mI | 5.04 | 0.81 | 5.04 | 1.04 | 0.846 | |

| NAA | 7.84 | 0.95 | 8.37 | 0.75 | 0.336 | |

| Glx | 14.54 | 2.66 | 13.37 | 1.31 | 0.183 | |

| mPCG | Cho | 1.63 | 0.24 | 1.65 | 0.07 | 0.439 |

| Cr | 6.76 | 1.22 | 6.82 | 0.99 | 0.698 | |

| mI | 5.86 | 1.36 | 5.33 | 0.62 | 0.055 | |

| NAA | 9.48 | 0.77 | 9.83 | 1.06 | 0.366 | |

| Glx | 12.50 | 1.44 | 13.08 | 2.36 | 0.190 | |

| mPC | Cho | 1.24 | 0.15 | 1.20 | 0.13 | 0.032* |

| Cr | 6.09 | 0.45 | 6.30 | 0.75 | 0.757 | |

| mI | 5.34 | 0.97 | 4.27 | 0.55 | 0.0004* | |

| NAA | 8.87 | 0.38 | 9.66 | 0.81 | 0.036* | |

| Glx | 14.10 | 1.09 | 14.12 | 1.58 | 0.867 |

LpAC: left pregenual anterior cingulate gyrus; RpAC: right pregenual anterior cingulate gyrus; mPCG: midline posterior cingulate gyrus; mPC: midline precuneus

significant protected post-hoc ANCOVA

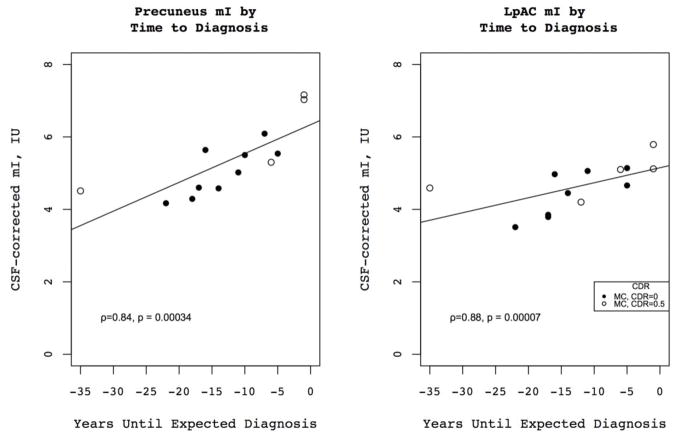

Metabolite levels for MCs and NCs are listed in Table 3; while we did not use Cr-normalized values for this analysis, we do report them for reference in Table 4. Among MCs, the level of mI in the LpAC (ρ=−0.88, p=0.00007) and mPC (ρ=−0.84, p=0.0003) was higher in subjects with age closer to the estimated age of dementia diagnosis. Levels of Cr, Cho and mI all increased in the mPCG as onset of dementia approached, as did levels of Glx in the mPC however these findings did not remain significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. There were no other significant correlations between metabolite levels and time until expected onset of dementia in MCs.

Table 4.

Cr-normalized 1H-MRS mean metabolite values by voxel in MCs and NCs.

| MC | MC | NC | NC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voxel | Metabolite | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| LpAC | Cho/Cr | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.10 |

| mI/Cr | 0.91 | 0.13 | 0.90 | 0.16 | |

| NAA/Cr | 1.51 | 0.13 | 1.60 | 0.28 | |

| Glx/Cr | 2.58 | 0.45 | 2.65 | 0.79 | |

| RpAC | Cho/Cr | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.08 |

| mI/Cr | 0.87 | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.11 | |

| NAA/Cr | 1.41 | 0.23 | 1.55 | 0.24 | |

| Glx/Cr | 2.61 | 0.49 | 2.51 | 0.49 | |

| mPCG | Cho/Cr | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| mI/Cr | 0.88 | 0.16 | 0.79 | 0.05 | |

| NAA/Cr | 1.44 | 0.20 | 1.47 | 0.15 | |

| Glx/Cr | 1.91 | 0.33 | 1.94 | 0.26 | |

| mPC | Cho/Cr | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.03 |

| mI/Cr | 0.88 | 0.14 | 0.67 | 0.05 | |

| NAA/Cr | 1.49 | 0.14 | 1.57 | 0.16 | |

| Glx/Cr | 2.38 | 0.15 | 2.29 | 0.27 |

LpAC: left pregenual anterior cingulate gyrus; RpAC: right pregenual anterior cingulate gyrus; mPCG: midline posterior cingulate gyrus; mPC: midline precuneus

Discussion

In this study we found that preclinical ADAD MCs had higher levels of mI in the mPC than NCs, and that levels of mI in the mPC as well as the LpAC increased in association with progressive neurodegeneration. mI levels have been consistently shown to be above-normal in 1H MRS studies of AD and elevated levels of mI appear to predate the development of dementia or alterations in other metabolites (K. Kantarci et al., 2000). The mean time until expected onset of dementia for MCs in this study was more than 12 years, confirming that mI is highly sensitive to early pathologic changes in AD.

mI is found primarily in glial cells, particularly astrocytes, where it appears to function as a cellular osmolyte and in cell signaling (Fisher, Novak, & Agranoff, 2002). Elevated levels are thought to represent glial proliferation and/or greater cell size(Soares & Law, 2009). In a postmortem study examining pathologic correlates of 1H MRS metabolites in AD, mI/Cr has been shown to correlate with Aβ burden (Murray et al., 2014) rather than gliosis or neurofibrillary tangles. Since early pathologic changes in AD are predominantly related to amyloid deposition, this supports the role of mI as an early marker of AD pathology.

Studies of late-onset AD which have consistently shown diffusely below-normal levels of NAA (K. Kantarci et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2014), and reductions in NAA/Cr levels have been shown to correlate with reduced synaptic integrity and increased hyperphosphorylated tau pathology (Murray et al., 2014). The NAA peak reflects mainly N-acetylaspartate with a smaller contribution from N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG). NAA is synthesized by neuronal mitochondria and is predominantly found in neurons, although it is eventually transported out and degraded on the oligodendrocyte cell membrane; the exact function is unknown although it is thought to possibly represent an osmolyte (Hajek & Dezortova, 2008; Soares & Law, 2009). NAAG is synthesized from NAA and glutamate in neurons and appears to be involved in signaling local energy balance (Baslow, 2016). Depressed levels of NAA are therefore thought to reflect either neuronal loss, impaired neuronal functioning or energy metabolism. We found that levels of NAA in the mPC and LpAC were lower in MCs than in NCs. The Glx peak, which represents glutamate and glutamine, has been shown to be below-normal in the anterior cingulate in AD (Huang et al., 2016); we also found MCs to have lower levels of Glx in the LpAC compared to NCs.

MCs also had elevated mPC Cho compared to NCs. The Cho peak includes phosphocholine and other precursors needed for synthesis of membranes; increased levels are thought to reflect membrane disruption, cellular proliferation or inflammation (Hajek & Dezortova, 2008). Choline is also a precursor of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, the deficit of which is an important part of the pathophysiology of AD. In late-onset AD, the role of Cho has been less clear with some studies supporting elevated levels in AD and others finding no effect (K. Kantarci et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2015); in addition, studies of neuropathological correlates of 1H MRS metabolites in AD have not shown a clear correlation between Cho/Cr and AD pathology (Kejal Kantarci et al., 2008; Murray et al., 2014).

To our knowledge only one prior study has looked at 1H MRS metabolites in ADAD. This single-voxel study examined metabolic changes in the posterior cingulate and found that presymptomatic MCs had depressed NAA/Cr and NAA/mI in the region of interest. In the present study, the mean level of mPCG NAA was lower in MCs but the difference was not statistically significant. This discrepancy may be partially explained by a longer time until expected diagnosis in our subjects (12.3 years vs 9.8); as mentioned above, NAA has been shown to correlate with hyperphosphorylated tau pathology and reduced synaptic integrity, which are thought to occur later in AD than amyloid deposition (Jack et al., 2010); thus it is possible that the difference between MCs and NCs would continue to diverge with time until the difference reached statistical significance. Other factors that may have contributed to our not fully replicating the previous finding include technical factors and choice of voxel placement. We did find that both mI and Cho in this region increased as age of expected diagnosis approached; although this finding was not significant after correction for multiple comparisons, it does suggest that this area is affected relatively early in the disease as is known from studies of late-onset AD.

Our study was limited by the relatively small number of subjects enrolled (n=27). This is a common problem in studies of ADAD due to its relative rarity as a cause of AD. However, despite the small number of subjects we were able to show clear differences between MCs and NCs. MCs were also younger on average than NCs, likely in part because we excluded persons with clinical dementia, and the typical age of onset of clinical dementia in ADAD is frequently in the 5th decade. However since there is a decrease in NAA and increase in mI in normal aging (Minati, Grisoli, & Bruzzone, 2007) the increased age in NC controls would have acted to decrease between group differences, and thus would not impact the validity of our results. Finally, two NCs were blindly rated 0.5 on the CDR; given their young ages (37 and 39), the etiology was considered unlikely to represent early AD and more likely due to heightened anxiety and potentially depression associated with living at-risk for ADAD. CDR rating is dependent on both the report of informants and subjects and anticipation of the onset of symptoms may have led them to emphasize subtle symptoms not related to incipient neurodegenerative disease.

In summary, levels of brain metabolites are altered in MCs for ADAD compared to NCs many years prior to expected onset of clinical dementia. mI is most sensitive as an early marker of AD pathology. For studies of disease-modifying interventions targeting prevention of neuronal death, MRS measures may provide an important surrogate outcome measure.

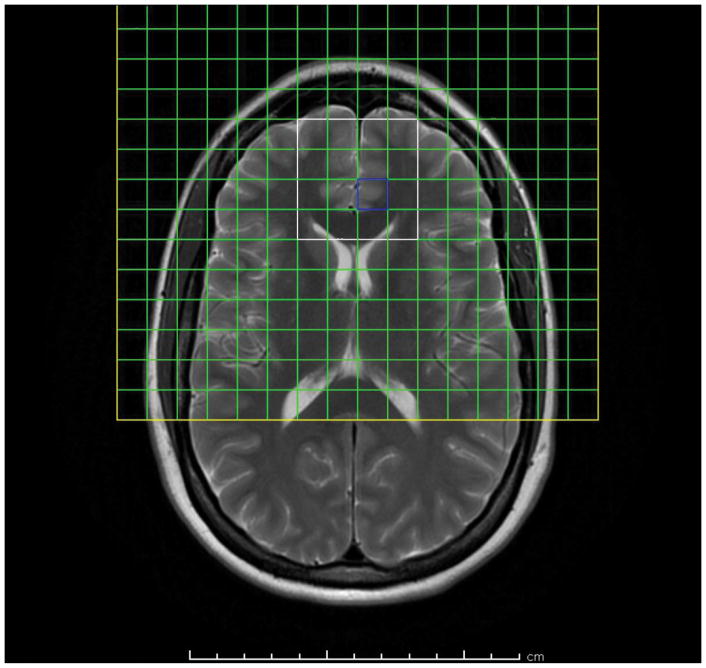

Figure 1.

T2-weighted axial-oblique (parallel to genu-splenium line) MRI of the human brain showing prescription of anterior cingulate 1H MRSI slab (yellow box). Usable spectra are obtained from the voxels (green squares) within the PRESS excitation volume (white box). Posterior mesial voxels within the slab sample left and right pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (LpAC, RpAC), anterior mesial voxels sample mesial superior frontal cortex, lateral voxels sample prefrontal white matter (anterior corona radiata).

Figure 2.

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI of the human brain showing prescription of midline parietal 1H MRSI slab (yellow box). Usable spectra are obtained from the voxels (green squares) within the PRESS excitation volume (white box).

Figure 3.

Metabolite levels by carrier status and CDR for voxels/metabolite combinations for which there was a significant effect by carrier status. Horizontal bars represent mean metabolite values for the entire group (including individuals with both CDR 0 and 0.5).

Figure 4.

Correlation of PC and LpAC mI with years until expected diagnosis for MCs for asymptomatic (CDR=0) and questionably symptomatic (CDR=0.5) individuals.

Table 2.

Results of multivariate analysis of covariance by voxel

| Voxel | F | p |

|---|---|---|

| LpAC | 3.067 | 0.040 |

| RpAC | 0.761 | 0.592 |

| mPCG | 1.461 | 0.264 |

| mPC | 4.400 | 0.013 |

LpAC: left pregenual anterior cingulate gyrus; RpAC: right pregenual anterior cingulate gyrus; mPCG: midline posterior cingulate gyrus; mPC: midline precuneus

Table 5.

Correlation between metabolite levels and expected time to onset of AD

| Spearman ρ, years until expected diagnosis | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LpAC | Cho | −0.29 | 0.344 |

| Cr | −0.37 | 0.212 | |

| Gx | 0.36 | 0.229 | |

| mI | −0.88 | 0.00007* | |

| NAA | −0.50 | 0.079 | |

| RpAC | Cho | −0.17 | 0.578 |

| Cr | −0.48 | 0.097 | |

| Gx | −0.45 | 0.123 | |

| mI | −0.45 | 0.123 | |

| NAA | −0.01 | 0.969 | |

| mPCG | Cho | −0.76 | 0.003 |

| Cr | −0.68 | 0.010 | |

| Gx | −0.26 | 0.388 | |

| mI | −0.76 | 0.003 | |

| NAA | −0.41 | 0.160 | |

| mPC | Cho | −0.52 | 0.072 |

| Cr | −0.46 | 0.117 | |

| Gx | −0.66 | 0.015 | |

| mI | −0.84 | 0.00034* | |

| NAA | 0.04 | 0.890 |

LpAC: left pregenual anterior cingulate gyrus; RpAC: right pregenual anterior cingulate gyrus; mPCG: midline posterior cingulate gyrus; mPC: midline precuneus

significant after Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P50 AG0005142, K08 AG022228, P50 AG016570.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P50 AG0005142, K08 AG022228, P50 AG016570.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards:

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Alger J. Quantitative Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and Spectroscopic Imaging of the Brain: A Didactic Review. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;21(2):115–128. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0b013e31821e568f.Quantitative. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baslow MH. An answer to “The Nagging Question of the Function of N-Acetylaspartylglutamate”. Neuroscience Communications. 2016:2–7. doi: 10.14800/nc.844. [DOI]

- Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC … Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(9):795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SK, Novak JE, Agranoff BW. Inositol and higher inositol phosphates in neural tissues: Homeostasis, metabolism and functional significance. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2002;82(4):736–754. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick BD, Kyoon I, Satlin A, Heup K, Kim MJ, Yurgeluntodd DA, … Renshaw PF. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the temporal lobe in Alzheimer’s disease. 2004;28:1313–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbolt AK, Waldman AD, MacManus DG, Schott JM, Frost C, Cipolotti L, … Rossor MN. MRS shows abnormalities before symptoms in familial Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;66:718–722. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201237.05869.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek M, Dezortova M. Introduction to clinical in vivo MR spectroscopy. European Journal of Radiology. 2008;67(2):185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Liu D, Yin J, Qian T, Shrestha S, Ni H. Glutamate-glutamine and GABA in brain of normal aged and patients with cognitive impairment. European Radiology. 2016:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4669-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, … Trojanowski JQ. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, … Trojanowski JQ. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(1):119–128. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Aisen PS, Trojanowski JQ … Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Evidence for ordering of Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Archives of Neurology. 2011;68(12):1526–35. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K, Jr, Xu CRJ, Campeau YC, O’Brien NG, Smith PC, GE, … Petersen RC., MDP Regional Metabolic Patterns in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’S Disease a 1 H Mrs Study. Neurology. 2000;55(2):210–217. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantarci K, Knopman DS, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, … Jack CR. Alzheimer disease: postmortem neuropathologic correlates of antemortem 1H MR spectroscopy metabolite measurements. Radiology. 2008;248(1):210–20. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R, Terry R, DeTeresa R, Brown T, Davies P, Fuld P, … Peck A. Clinical, pathological, and neurochemical changes in dementia: A subgroup with preserved mental status and numerous neocortical plaques. Annals of Neurology. 1988;23(2):138–144. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metastasio A, Rinaldi P, Tarducci R, Mariani E, Feliziani FT, Cherubini A, … Mecocci P. Conversion of MCI to dementia: Role of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neurobiology of Aging. 2006;27(7):926–932. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minati L, Grisoli M, Bruzzone MG. MR spectroscopy, functional MRI, and diffusion-tensor imaging in the aging brain: a conceptual review. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2007;20(1):3–21. doi: 10.1177/0891988706297089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrego PJ, Fayed N, Pina MA. Conversion from mild cognitive impairment to probable Alzheimer’s disease predicted by brain magnetic resonance spectroscopy. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(4):667–675. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrego PJ, Fayed N, Sarasa M. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the prediction of early conversion from amnestic mild cognitive impairment to dementia: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. Clinical Dementia Rating: A Reliable and Valid Diagnostic and Staging Measure for Dementia of the Alzheimer Type. International Psychogeriatrics. 1997;9(Supplement S1):173–176. doi: 10.1017/S1041610297004870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray ME, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TG, Liesinger AM, Spychalla A, Zhang B, … Kantarci K. Early Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology detected by proton MR spectroscopy. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2014;34(49):16247–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2027-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J, Tobias MC, Hudkins M, London ED. Glutamatergic neurometabolites during early abstinence from chronic methamphetamine abuse. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;18(3):1–9. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyu059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR in Biomedicine. 2001;14(4):260–264. doi: 10.1002/nbm.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringman JM, Younkin SG, Pratico D, Seltzer W, Cole GM, Geschwind DH, … Cummings JL. Biochemical markers in persons with preclinical familial Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;71(2):85–92. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303973.71803.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryman DC, Acosta-Baena N, Aisen PS, Bird T, Danek A, Fox NC, … Bateman RJ. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;83(3):253–260. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MMB, de Strooper B, Frisoni GB, Salloway S, Van der Flier W Maria. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet (London, England) 2016;388(10043):505–517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seese RR, O’Neill J, Hudkins M, Siddarth P, Levitt J, Tseng B, … Caplan R. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and thought disorder in childhood schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;133(1–3):82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck DW, Sandor-Leahy SR, Schaper KA, Rottenberg DA, Leahy RM. Magnetic Resonance Image Tissue Classification Using a Partial Volume Model. NeuroImage. 2001;13(5):856–876. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares DP, Law M. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the brain: review of metabolites and clinical applications. Clinical Radiology. 2009;64(1):12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targosz-gajniak MG, Siuda JS, Wicher MM, Banasik TJ, Bujak MA, Augusciakduma AM, Opala G. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy as a predictor of conversion of mild cognitive impairment to dementia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2013;335(1–2):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Tan L, Wang HF, Liu Y, Yin RH, Wang WY, … Yu JT. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Alzheimer’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46(4):1049–1070. doi: 10.3233/JAD-143225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Song X, Bartha R, Beyea S, Arcy RD. Advances in High-Field Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Alzheimer’s Disease. 2014;(1):367–388. doi: 10.2174/1567205011666140302200312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]