Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

The present study analyzed the postoperative outcomes in patients who underwent hepatectomy or pancreatectomy, with a history of intra-abdominal surgery involving other organs, to elucidate surgical efficacy.

Methods

We examined the perioperative parameters in 28 patients who underwent hepatectomy (n=12) and pancreatectomy (n=16) after receiving prior abdominal organ resection (esophagectomy, n=2; gastrectomy, n=5; resection of small intestine, n=2; appendectomy, n=5; colorectal resection, n=9; hepatectomy, n=1; cholecystectomy, n=3; splenectomy, n=2, pancreatectomy ,right adrenectomy, nephrectomy and myoma uteri, n=1 each).

Results

Age, gender, a history of comorbidities, and primary diseases were not significantly different between the groups. The present operation was predominantly indicated for liver metastases in all patients undergoing hepatectomy. Several diseases were detected in pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) patients. Laboratory data were not significantly different between groups. Although operating time and blood loss during hepatectomy did not differ significantly between the groups, the operating time was significantly longer in patients undergoing PD compared with distal pancreatectomy (p<0.05). Red cell blood transfusion was most frequently used in patients who underwent major hepatectomy and PD (p<0.05). The prevalence of postoperative complications was not significantly different between groups. Hospital death was not observed and the period of hospital stay did not differ between groups.

Conclusions

Carefully scheduled hepatectomy or pancreatectomy is safe even in cases with prior abdominal surgery under the present strategy.

Keywords: Hepatectomy; Pancreatectomy, Previous history; Abdominal surgeries; Operative difficulties

INTRODUCTION

Repeated operations have been undertaken to enhance curative and survival rates following the initial operation, particularly for colorectal or upper gastrointestinal malignancies. Postoperative adhesion in the digestive tract is the biggest challenge. In cases of hepatectomy or pancreatectomy for malignancies, longer operative time and careful dissection around important organs or vessels are required due to severe adhesion.1 In the modern era, the dissection devices, and high-quality diathermy or energy devices have been markedly improved to reduce thermal injuries to the surrounding tissue.2 In particular, the intra-operative blood loss may be correlated with the severity of adhesion.1 Thus, the patient position, operative approaches, and the incision site are often selected to avoid the adherent areas.

The present study examined the perioperative parameters and patient outcomes using surgical records of 28 patients who underwent hepatic resection or pancreatectomy for malignancies, in order to elucidate the operative difficulties associated with a retrospective cohort study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 28 consecutive patients undergoing hepatic or pancreatic resection who had a history of surgeries for other intra-abdominal organs at the Division of Hepatobiliary-pancreatic Surgery of the University Of Miyazaki Faculty Of Medicine between April 2015 and June 2017 were retrieved from the institutional surgical database. Twelve patients undergoing hepatectomy for liver malignancies and 16 undergoing pancreatectomy were reviewed in the present study. Those with combined vascular or other organ resections were excluded as the operative strategies varied. The subjects enrolled in the present analysis comprised 19 males and 9 females, and the median patient age at the time of surgery was 61.8 years (range, 24–77 years) for hepatectomy and 54.4 years (range, 39–81 years) for pancreatectomy. Our protocol for indication of hepatectomy was not influenced by indication for resection of other organs. We examined preoperative clinical parameters, operative procedures, surgical records, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and hospital stay in the present series.

Demographics

Chronic hepatitis was observed in three patients (25%) in the hepatectomy group. While the liver was normal in eight patients chemotherapy-associated chronic liver injury was observed in three cases. The Child-Pugh classification A was observed in all patients and Liver Damage Grade B was observed in three cases (15%). Diseases included hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in two patients, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) in none, and metastatic liver tumor in nine patients. Hepatectomy included hemi-hepatectomy or greater (n=3), sectionectomy (n=1), segmentectomy (n=3), and limited resection (n=4, including laparoscopic resection in 2). Radical hepatectomy was performed to remove the hepatic tumor without leaving any residual tumor. The volume of resectable liver was estimated based on the indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min (ICGR15) using Takasaki's formula. Furthermore, the acceptable hepatic function for hepatectomy was limited to ICGR15 <40%, Child-Pugh classification A or B, and total bilirubin level of <2 mg/dL. The expected liver volume for resection, excluding the tumor, was measured by computed tomography (CT) volumetry.

Pancreatitis accompanying hepatic disease was observed in two patients (13%) in the pancreatectomy group, while the liver was normal in eight patients and chemotherapy-associated chronic liver injury was observed in three cases. Diseases included pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in six patients, intraductal papillary mucin producing neoplasm (IPMN) in three, distal bile duct carcinoma (BDC) in two, ampullar adenocarcinoma in three, and duodenal adenocarcinoma in two cases. Hepatectomy included pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) in nine (including pyrolus-preserving PD in four patients) and distal pancreatectomy (DP) in seven cases. Radical hepatectomy was performed to remove the hepatic tumor without leaving any residual tumor in all. Laparoscopic history was not found in this study. Anesthesia and patient data were retrieved from the institutional database. The institutional ethics committee approved the present study on 2017/10/20 (reference number O-0203) and the study was accomplished by March 2018.

Statistical analysis

All continuous data were expressed as the mean±standard deviation. Data for different groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance and examined by the Student's t-test. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered significant. The linear regression formula was used to correlate the parameters. The PASW Statistics for Windows version 18.0.0 software (SPSS, an IBM Company, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Surgical history

Among the 28 patients included in the present study, hepatic resection was performed in 12 cases (limited resection in 5, segmentectomy or sectionectomy in 4, and major hepatectomy in 3) and pancreatectomy in 16 (PD in 12 and distal pancreatectomy in 4). Prior abdominal surgeries consisted of esophagectomy in 2, gastrectomy in 5, resection of the small intestine in 2, appendectomy in 5, colorectal resection in 9, hepatectomy in 1, cholecystectomy in 3, splenectomy in 2, and pancreatectomy, right adrenectomy, nephrectomy, and removal of uterine myoma in 1 each.

Clinicopathological parameters

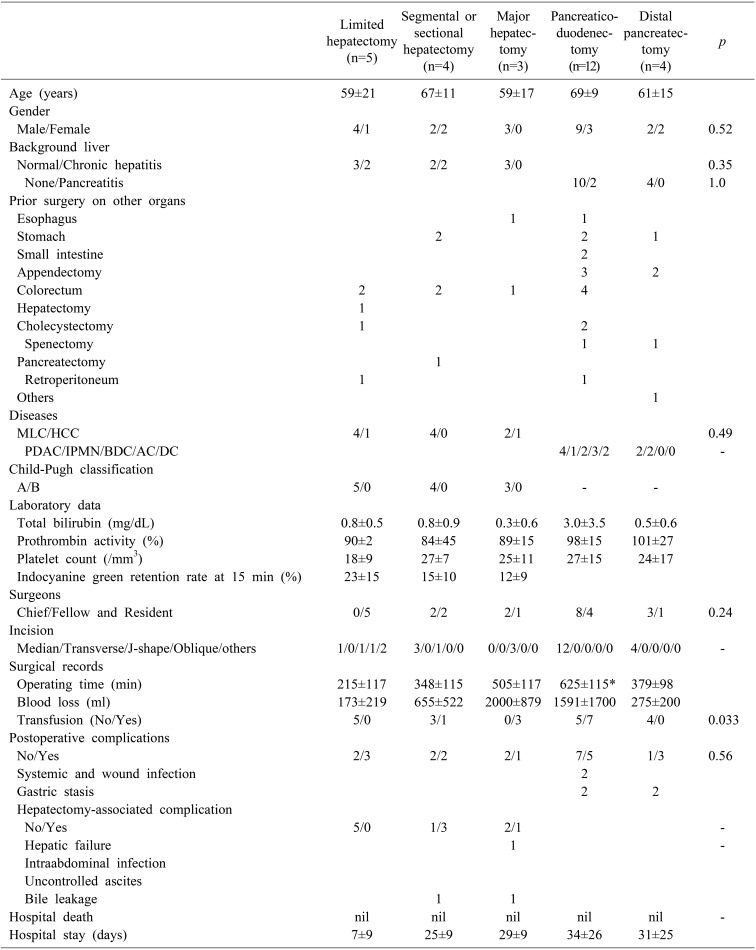

The demographics of patients who underwent hepatectomy or pancreatectomy after prior abdominal surgery are shown in Table 1. Age and gender did not differ significantly between groups. The incidence of chronic hepatic injury was not significantly different between the hepatectomy groups, and that of pancreatitis did not significantly vary between the pancreatectomy groups. Patients who underwent hepatectomy, showed a history of different abdominal surgeries, without any significant trends, and in those who underwent pancreatectomy, colectomy was predominantly performed. The present operation was primarily conducted for metastatic liver disease in all patients undergoing hepatectomy. Several diseases were observed in PD patients, but only pancreatic carcinoma and intraductal papillary neoplasm were observed in distal pancreatectomy patients. Child-Pugh A was the predominant class in all hepatectomy patients. Laboratory data of total bilirubin level, ICGR15, prothrombin activity, and platelet count were not significantly different between the groups. The prevalence of chief operators among surgeons with varying levels of experience did not differ significantly between the groups.

Table 1. Demographics of patients who underwent hepatectomy or pancreatectomy after prior abdominal surgeries.

No significant difference in continuous parameters between groups

*; p<0.05 vs. Distal pancreatectomy, #; p=0.75 vs. Distal pancreatectomy

MLC, metastatic liver carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; IPMN, intraductal papillary mucin-producing neoplasm; BDC, bile duct carcinoma; AC, ampullar carcinoma; DC, duodenal carcinoma

Surgical outcomes

The median incision was predominantly performed for pancreatectomy patients. Although operating time and blood loss did not vary significantly between groups undergoing hepatectomy, the operating time was significantly longer in patients undergoing PD in comparison with distal pancreatectomy (p=0.033). Red blood cell transfusion was most frequently used in patients who underwent major hepatectomy and PD (p<0.05). The prevalence of postoperative complications did not vary significantly between groups, and hepatectomy-associated complications in patients were not significantly different between groups. Hospital death was not observed and the length of hospital stay did not vary significantly between groups.

DISCUSSION

Recent advances in major hepatectomy and pancreatectomy have ensured patient safety via adequate preoperative evaluation of the functional liver reserve and improved postoperative management.1,3 Although patient prognosis has been improved with increased survival,1 further malignancies or other diseases require surgical intervention. Prior abdominal surgeries may influence subsequent abdominal surgeries and patient outcomes. Furthermore, increased surgical stress is anticipated preoperatively and decisions related to resection depend on patient condition or organ function. In particular, hepatic or pancreatic resections are relatively complicated and invasive in comparison with other digestive tract surgeries. Additional adverse complications associated with these operations may lead to systemic damage or lethal conditions. The present series of 28 patients involved those who underwent scheduled hepatic or pancreatic resections. Our aim in this study was to elucidate whether prior abdominal surgeries influenced adversely the subsequent hepatectomy or pancreatectomy.

The number of subgroups was limited, particularly for hepatectomy. The prevalence of sectionectomy or major hepatectomy tended to be lower in our series. After prior abdominal surgery, manipulation of adhesive parts around the major vessels may be difficult; however, such manipulations are usually required for hepatectomy or pancreatectomy, except in partial resections. Preoperatively, surgeons may hesitate and alter the indication for the operation. Although surgery was conducted in all patients in the present series, the indications and surgical decisions were unclear based on patient charts. The second or third operation was performed in elderly patients in previous reports;4 however, the patient age in our study ranged around 60 years, which was not different from other studies involving patients without prior abdominal operations.5,6,7,8 Considering this selective bias, secondary surgeries for elderly patients and high-risk surgical candidates were likely avoided at our institute. Even in younger patients, a greater risk of intraoperative (bowel injury) and postoperative adverse events (surgical site infections) was previously reported.9,10 In our study, the prevalence of background diseases, such as cirrhosis and chronic pancreatitis, was lower, and organ function was well preserved.

Although the prior surgeries varied, gastrectomy and colorectal surgery accounted for 45% of all the surgeries, and were carried out via median incision laparotomy leaving behind possible intra-abdominal adhesions. Kim et al. and Yamamoto et al. reported that these laparotomies exhibited a high degree of adhesion and increased the severity.11,12 Hepatectomy and pancreatectomy usually require laparotomy on the upper median line, and the operative time may be prolonged in order to perform adhesiolysis. Furthermore, following gastrectomy, lymphadenectomy and reconstructed intestines led to adhesions. In cases where severe adhesion was expected, we preferred to perform thoraco-abdominal laparotomy with an oblique incision, which uses a different part of the initial wound, in patients undergoing hepatic resections involving the subphrenic lesion of the right liver.13,14,15,16 The author performed hepatectomy using this incision safely at this stage.16 This incision was selected in one hepatectomy in the present series. Although, fewer hepatectomies and pancreatectomies occurred during this period, reoperation after hepatectomy was common.17

Surgical skills involving dissection of postoperative adhesions are important, and 46% of trainee residents and fellows performed this operation. According to the author's previous study and other similar reports, surgical records and patient outcomes involving hepatectomy or pancreatectomy did not differ between instructors and trainees following adequate instruction supported by experienced surgeons.18,19,20,21 The difference in surgical experience may not have influenced surgical records and outcomes in the present study (data not shown). In the present study, operating time, blood loss, and red cell transfusion increased with the extent of hepatectomy and PD, and this was consistent with previous reports.22,23 Blood loss related to transfusion was minor under limited hepatectomy and distal pancreatectomy, suggesting that intra-abdominal adhesion may not influence such operations. Operating time and blood loss were greatly increased in major hepatectomy and PD, especially in patients without prior operation.23 Therefore, it is necessary to fully consider the indications for major operations based on patient status and prepare adequately for blood transfusions.

Postoperative complications were not severe and only a single patient undergoing major hepatectomy developed transient hepatic failure, without any death in the present series. The hospital stay was not extended. Sepsis and surgical site infection were observed only in two cases (8%); therefore, the selected patients may not have been affected by severe surgical stress due to prior operations and adhesion, as reported previously.7,8

We investigated hepatectomy or pancreatectomy in patients who underwent prior abdominal surgeries. The present study demonstrated good postoperative outcomes following careful pre- and perioperative management based on our usual indications. The current strategy ensures operative safety for hepatectomy or pancreatectomy in patients with prior abdominal surgery.

References

- 1.Mavros MN, Velmahos GC, Lee J, Larentzakis A, Kaafarani HM. Morbidity related to concomitant adhesions in abdominal surgery. J Surg Res. 2014;192:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JH, Min SK, Lee H, Hong G, Lee HK. The safety and risk factors of major hepatobiliary pancreatic surgery in patients older than 80 years. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2016;91:288–294. doi: 10.4174/astr.2016.91.6.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okabayashi K, Ashrafian H, Zacharakis E, Hasegawa H, Kitagawa Y, Athanasiou T, et al. Adhesions after abdominal surgery: a systematic review of the incidence, distribution and severity. Surg Today. 2014;44:405–420. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golfinopoulos V, Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Treatment of colorectal cancer in the elderly: a review of the literature. Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nanashima A, Abo T, Nonaka T, Hidaka S, Takeshita H, Morisaki T, et al. Comparison of postoperative morbidity in elderly patients who underwent pancreatic resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1141–1146. doi: 10.5754/hge10777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nanashima A, Abo T, Nonaka T, Fukuoka H, Hidaka S, Takeshita H, et al. Prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatic resection: are elderly patients suitable for surgery? J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:284–291. doi: 10.1002/jso.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panis Y, Maggiori L, Caranhac G, Bretagnol F, Vicaut E. Mortality after colorectal cancer surgery: a French survey of more than 84,000 patients. Ann Surg. 2011;254:738–743. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823604ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Refaie WB, Parsons HM, Habermann EB, Kwaan M, Spencer MP, Henderson WG, et al. Operative outcomes beyond 30-day mortality: colorectal cancer surgery in oldest old. Ann Surg. 2011;253:947–952. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318216f56e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto S, Watanabe M, Hasegawa H, Baba H, Kitajima M. Short-term surgical outcomes of laparoscopic colonic surgery in octogenarians: a matched case-control study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:95–100. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200304000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masoomi H, Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Mills S, Carmichael JC, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ. Risk factors for conversion of laparoscopic colorectal surgery to open surgery: does conversion worsen outcome? World J Surg. 2015;39:1240–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-2958-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim IY, Kim BR, Kim YW. Impact of prior abdominal surgery on rates of conversion to open surgery and short-term outcomes after laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto M, Okuda J, Tanaka K, Kondo K, Asai K, Kayano H, et al. Effect of previous abdominal surgery on outcomes following laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:336–342. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827ba103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pack GT, Baker HW. Total right hepatic lobectomy; report of a case. Ann Surg. 1953;138:253–258. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195308000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donadon M, Costa G, Gatti A, Torzilli G. Thoracoabdominal approach in liver surgery: how, when, and why. Updates Surg. 2014;66:121–125. doi: 10.1007/s13304-013-0244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubota K. Right hepatic lobectomy with thoracotomy: a description (with video) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:30–37. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0446-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nanashima A, Sumida Y, Tobinaga S, Shindo H, Shibasaki S, Ide N, et al. Advantages of thoracoabdominal approach by oblique incision for right-side hepatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:148–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faber W, Seehofer D, Neuhaus P, Stockmann M, Denecke T, Kalmuk S, et al. Repeated liver resection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1189–1194. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ejaz A, Spolverato G, Kim Y, Wolfgang CL, Hirose K, Weiss M, et al. The impact of resident involvement on surgical outcomes among patients undergoing hepatic and pancreatic resections. Surgery. 2015;158:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cocieru A, Saldinger PF. HPB surgery can be safely performed in a community teaching hospital. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1853–1857. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nanashima A, Sumida Y, Abo T, Tanaka K, Takeshita H, Hidaka S, et al. Principle of perioperative management for hepatic resection and education for young surgeons. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:587–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumida Y, Nanashima A, Abo T, Tobinaga S, Araki M, Kunizaki M, et al. Stepwise education for pancreaticoduodenectomy for young surgeons at a single Japanese institute. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1046–1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen JY, Feng J, Wang XQ, Cai SW, Dong JH, Chen YL. Risk scoring system and predictor for clinically relevant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5926–5933. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nanashima A, Abo T, Hamasaki K, Wakata K, Kunizaki M, Nakao K, et al. Predictive parameters of intraoperative blood loss in patients who underwent pancreatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:1217–1221. doi: 10.5754/hge11376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]