Abstract

Backgrounds/Aims

Several studies report worse prognosis after left-side compared to right-side liver resection in patients with perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. In this study, we compared outcomes of left-side and right-side resections for Bismuth type III hilar cholangiocarcinoma and analyzed factors affecting survival.

Methods

From May 1995 to December 2012, 179 patients underwent surgery at Samsung Medical Center for type III hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Among these patients, 138 received hepatectomies for adenocarcinoma with curative intent: 103 had right-side resections (IIIa group) and 35 had left-side resections (IIIb group). Perioperative demographics, morbidity, mortality, and overall and disease-free survival rates were compared between the groups.

Results

BMI was higher in the IIIa group (24±2.6 kg/m2 versus 22.7±2.8 kg/m2; p=0.012). Preoperative portal vein embolization was done in 23.3% of patients in the IIIa group and none in the IIIb group. R0 rate was 82.5% in the IIIa group and 85.7% in the IIIb group (p=0.796) and 3a complications by Clavien-Dindo classification were significantly different between groups (10.7% for IIIa versus 23.3% for IIIb; p=0.002). The 5-year overall survival rate was 33% in the IIIa group and 35% in the IIIb group (p=0.983). The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 28% in the IIIa group and 29% in the IIIb group (p=0.706). Advanced T-stages 3 and 4 and LN metastasis were independent prognostic factors for survival and recurrence by multivariate analysis.

Conclusions

No significant differences were seen in outcomes by lesion side in patients receiving curative surgery for Bismuth type III hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Keywords: Hilar cholangiocarcinoma, Klatskin tumor, R0 resection, Right hepatectomy, Left hepatectomy

INTRODUCTION

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HC) is a complex, rare disease with a poor prognosis.1,2,3,4,5 It is a malignancy arising from the bifurcation of the common hepatic duct in the hepatic hilum.6,7,8,9 It tends to spread along the bile duct and occasionally extends to the liver parenchyma through the bile duct wall.10

The Bismuth-Corlette classification system provides an anatomic description of the tumor location and longitudinal extension in the biliary tree. Type I lesions involve the common hepatic duct (CHD) immediately below the confluence; type II tumors involve the CHD and extend to the confluence but not beyond; type IIIa masses involve the CHD to the confluence and extend into the main right hepatic duct; type IIIb lesions involve the CHD to the confluence and extend into the main left hepatic duct; and type IV tumors involve the CHD and extend past the confluence involving both the right and left hepatic ducts.11 Assessment of resectability and surgical planning are based on imaging findings with focused evaluation of disease infiltration along the bile ducts and vascular involvement to determine the side and extent of the planned hepatectomy.12

Several studies report better prognosis after right-side compared to left-side liver resection for patients with HC.12,13,14,15,16,17 However, other studies show no significant differences in outcomes following right and left hepatectomy.2,16,18,19,20,21 The debate is not resolved. Therefore, we conducted this study to compare long-term outcomes following left-side and right-side resections for Bismuth type III HC. We also analyzed independent prognostic factors for survival and recurrence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

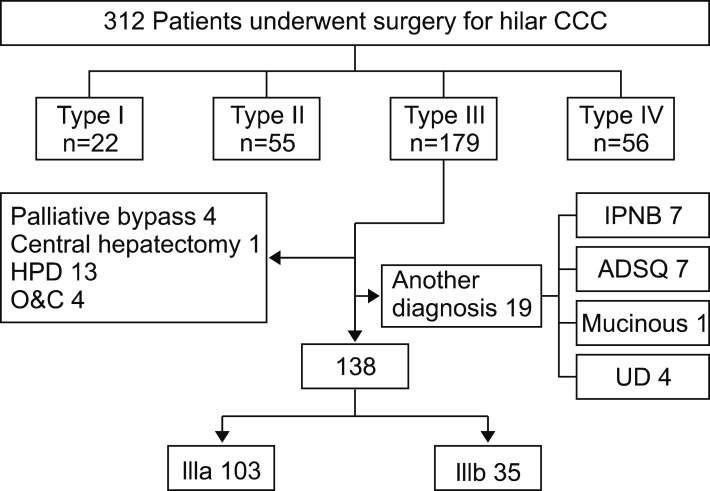

Between May 1995 and December 2012, a total of 312 patients with HC were candidates for surgery at Samsung Medical Center, South Korea. All data were prospectively collected and retrospectively reviewed. Of the patients, 179 had disease classified as type III HC based on the Bismuth-Corlette classification. Of these patients, 19 were excluded for diagnosis other than ductus adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma (n=7), mucinous carcinoma (n=1), undifferentiated carcinoma (n=4) or intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct (n=7). Another 22 patients were excluded because of their type of surgery: hepaticopancreaticoduodenectomy (n=13), central hepatectomy (n=1), palliative bypass surgery (n=4) or laparotomy only (n=4). The remaining 138 patients underwent right-side or left-side major hepatectomy for type IIIa or IIIb HC and were included in analyses: 103 (74.6%) required right hemihepatectomy or right trisectionectomy and 35 (25.4%) required left hepatectomy or left trisectionectomy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of patients.

In patients with borderline resectability due to limited remnant liver, we performed portal vein embolization to induce hypertrophy of the future remnant liver. Patients with HC usually had severe jaundice, indicating a high level of serum bilirubin, which could intoxicate hepatocytes and impair liver regeneration. Therefore, when serum bilirubin levels were elevated, we performed preoperative biliary drainage to relieve the biliary obstruction on the future remnant side of the liver. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) was the usual route for initial decompression. Although PTBD insertion was often started in the past, ERBD (endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage) has been preferred recently for patient convenience.

Patients were screened for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA 19-9 and underwent CT scanning. We implemented CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) routinely and PET was as indicated. When recurrent disease was suspected, MRI or PET was performed.

The seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system was applied and all samples were reviewed by an HBP-specific experienced pathologist. A microscopic positive resection margin (R1) was defined as presence of invasive carcinoma at the resection margin without macroscopic evidence of residual tumor, which was classified as R2. Carcinoma in situ (CIS)/high-grade dysplasia (HGD) at ductal resection margin without invasive component was considered R0.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was analyzed as time from the date of surgery until date of death or last contact. Disease-free survival (DFS) was measured from date of surgery to date of recurrence or last contact. For patients whose follow-up was discontinued, data from Statistics Korea were used.

Data were analyzed with SPSS, version 24 (IBM, New York, USA). Statistical significance was set as p<0.05. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to depict the overall survival and difference in survival between study groups. Factors found to be significant on univariate analysis for both OS and DFS were used for multivariate analysis by Cox proportional hazard model to determine the significant prognostic value of the factors.

RESULTS

Demographics and characteristics

The demographics and characteristics of patients are in Table 1. Three-quarters of patients had type IIIa HC (n=103) and 35 had type IIIb HC. No difference was observed between the two groups in sex, age, ASA class, comorbidities, preoperative lab data or frequency of preoperative biliary drainage. However, patients with type IIIa HC had higher BMI (24±2.6 in the IIIa group and 22.7±2.8 in the IIIb group; p=0.012) and received portal vein embolization more frequently (n=24, 23.3% in the IIIa group and n=0 in the IIIb group; p=0.001).

Table 1. Clinicopathologic characteristics.

Surgical outcome

No difference was observed between the two groups in caudate lobectomy, vascular resection, operating time, EBL, transfusion, postoperative hospital stay, T stage, size of tumor, LN metastasis, differentiation, resection margin, in-hospital mortality, or adjuvant therapy. Postoperative complications were classified according to Clavien-Dindo classification. More 3a complications such as wound dehiscence, intra-abdominal fluid collection, ascites and ileus were seen with type IIIa than type IIIb HC (p=0.002).

Pattern of recurrence

Patterns of recurrence are in Table 2. No difference was seen between the two groups in number of recurrences (65% in the IIIa group vs. 71.4% in the IIIb group; p=0.540) or isolated locoregional recurrence (26.2% in the IIIa group vs. 14.3% in the IIIb group; p=0.171), locoregional recurrence (32% in the IIIa group vs. 20% in the IIIb group; p=0.202), or distant metastasis (39.8% in the IIIa group vs. 51.4% in the IIIb group; p=0.242).

Table 2. Pattern of recurrence of IIIa and IIIb disease.

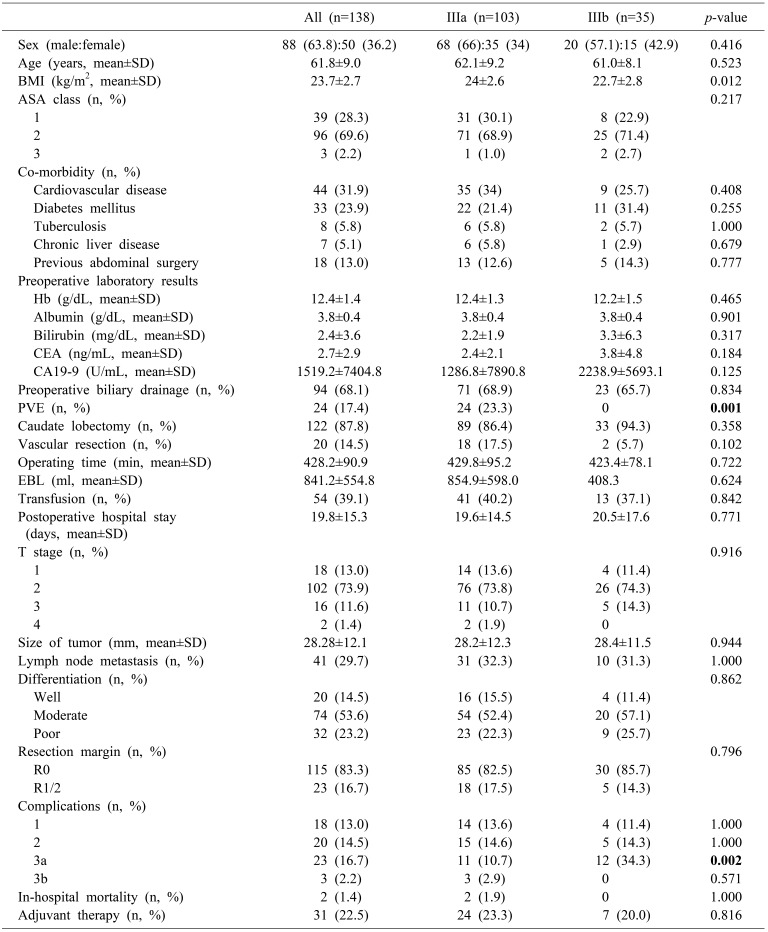

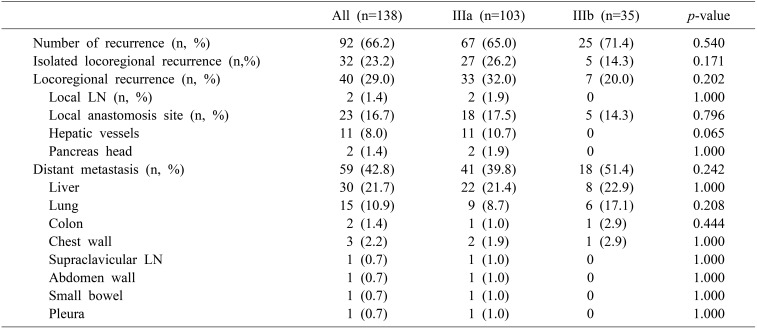

Survival outcomes

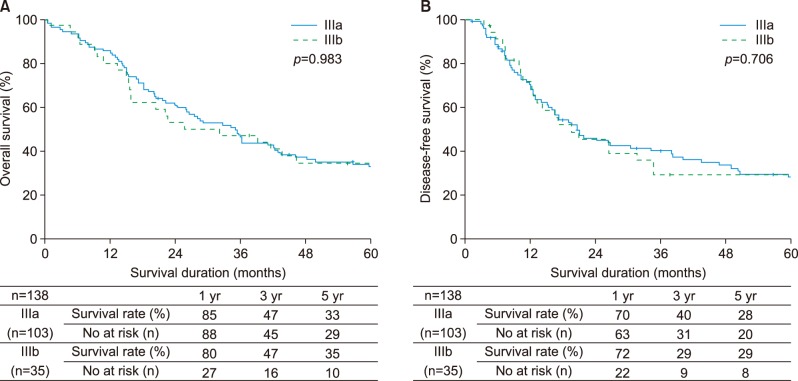

Median survival duration for all patients was 36 months. The 5-year overall survival rate was 33% while the corresponding disease-free survival rate was 28% (Fig. 2A, B). Differences were not significant. The 5-year overall survival rates were 33% for type IIIa HC and 35% for type IIIb HC, (p=0.983). The 5-year disease-free survival rates were 28% for type IIIa HC and 29% for type IIIb HC (p=0.706) (Fig. 3A, B).

Fig. 2. Survival analysis for all patients. (A) Overall survival, (B) Disease-free survival.

Fig. 3. Comparison of outcomes between IIIa and IIIb. (A) Overall survival, (B) Disease-free survival.

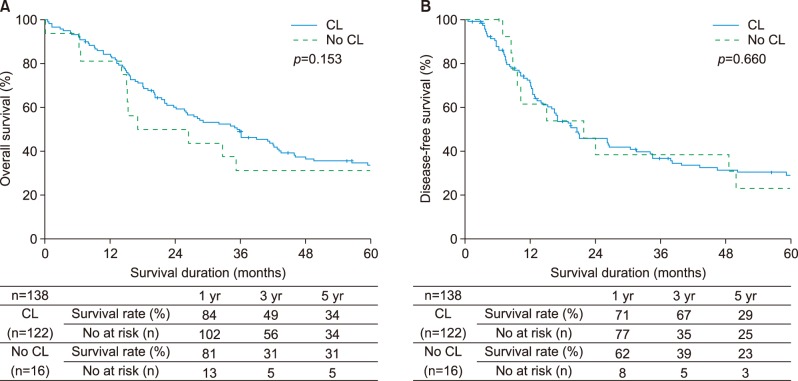

The 5-year overall survival rates for the two groups extended hepatectomy vs. simple hepatectomy were 40% for extended hepatectomy and 25% for simple hepatectomy (p=0.057). Overall survival was better for patients with extended hepatectomy, although this difference was not significant. Disease-free survival rates were 32% for extended hepatectomy and 23% for simple hepatectomy with no significant differences. The 5-year overall survival rates were 34% for the two groups extended hepatectomy with caudate lobectomy (CL) vs. 31% for simple hepatectomy without CL (p=0.153) while the corresponding disease-free survival rates were 29% and 23% (p=0.660). Differences were not significant (Fig. 4A, B).

Fig. 4. Comparison of outcomes between extended hepatectomy with caudate lobectomy and simple hepatectomy without caudate lobectomy. (A) Overall survival, (B) Disease-free survival.

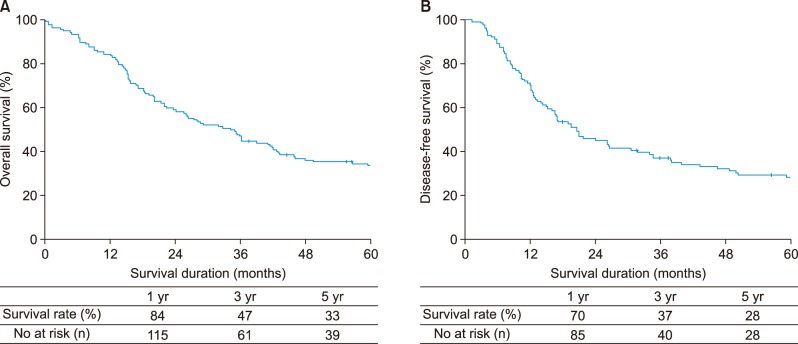

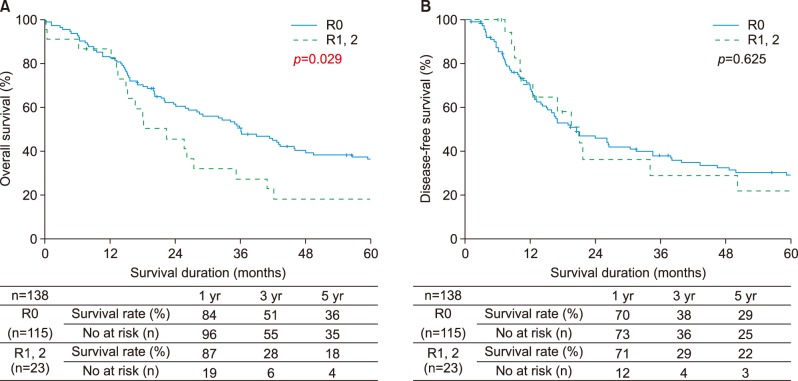

According to the resection margin status, 115 (8.33%) patients had R0 resection. The 5-year overall survival rate was 36% following R0 resection and 18% after R1 or R2 resection (p=0.029). The 5-year disease-free survival rates were 29% for patients who had R0 resection and 22% for patients with positive resection margins (p=0.625) (Fig. 5A, B).

Fig. 5. Comparison of outcomes between R0 resection and R1 or R2 resection. (A) Overall survival, (B) disease-free survival.

DISCUSSION

Advanced HC is a significant therapeutic challenge for biliary surgeons, as negative margin (R0) resection with minimizing postoperative mortality offers the only chance for long-term survival.20,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 Many studies recommend right-side hepatectomy as the resectional procedure for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma13,14,15,16,17,18 because right trisectionectomy is a more common and easier procedure. Another reason for the recommendation is an anatomical consideration because the left hepatic duct is longer than the right hepatic duct.18 It leads to better long-term outcomes in the right group with a lower incidence of local recurrence.12 However, recent studies show no significant difference between right hepatectomy and left hepatectomy. The length of the bile duct resected in right hepatectomies is similar to the length in left hepatectomies and shorter than in left hepatic trisectionectomies.18 Our study showed the same result. As the result of improved surgical skills, R0 resection rate between two groups makes no odds.

Our primary outcome was no significant difference in survival between patients with right and left hemihepatectomy. The long-term results were similar for patients with negative margin resections in a right group (82.5% had R0 resection for 35% 5-year overall survival rate) and a left group (85.7% had R0 resection for 39% 5-year overall survival rate).

For patients undergoing extended and simple hepatectomy, significantly more patients in the extended right hepatectomy group were obese (p=0.005), lost a lot of blood in the operation (p=0.014) and had a transfusion (p=0.008) and caudate lobectomy (p≤0.001) and R0 resection (p=0.038) compared to patients undergoing right hepatectomy. Significantly more patients with extended left hepatectomy had a lot of blood loss in the operation (p=0.038) and had a transfusion and R0 resection (p=0.006) compared to patients with left hepatectomy. The extended hepatectomy group had excellent negative margin resections. Due to gaps in operating skills, operating times >300 (min), EBL >600 ml and transfusion counts were high before 2010.

Significantly more patients had recurrence at the hepatic vessel compared to extended hepatectomy (p=0.009). More patients with simple hepatectomy without caudate lobectomy had recurrence at the hepatic vessel compared to patients with extended hepatectomy with caudate lobectomy (p=0.025).

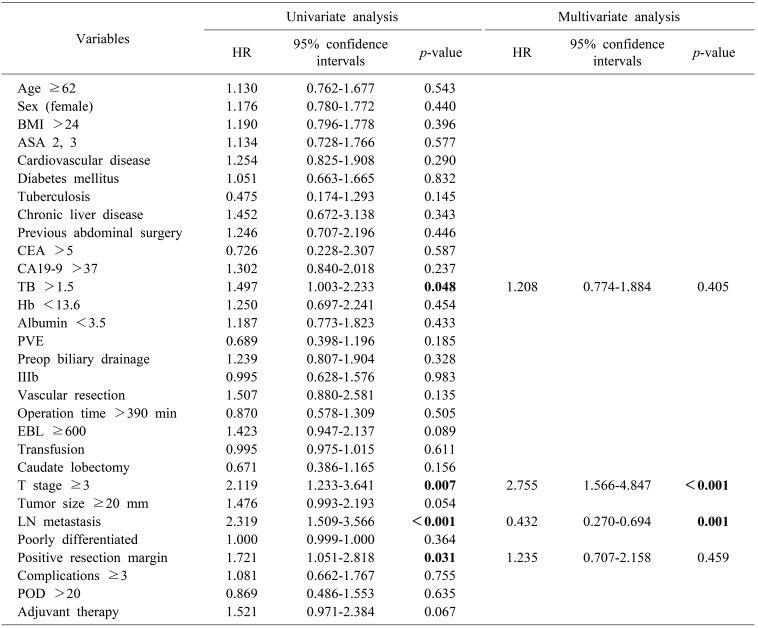

In univariate analysis, total bilirubin >1.5 (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.497, p=0.048), T stage ≥3 (HR: 2.119, p=0.007), LN metastasis (HR: 2.319, p<0.001) and positive resection margin (HR: 1.721, p=0.031) had a significant impact on overall survival. In multivariate analysis, advanced T stage ≥3 (HR: 2.755, CI: 1.566-4.847, p<0.001) and LN metastasis (HR: 0.432; 95% CI: 0.270-0.694; p=0.001) were significant prognostic factors for survival (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors influencing survival.

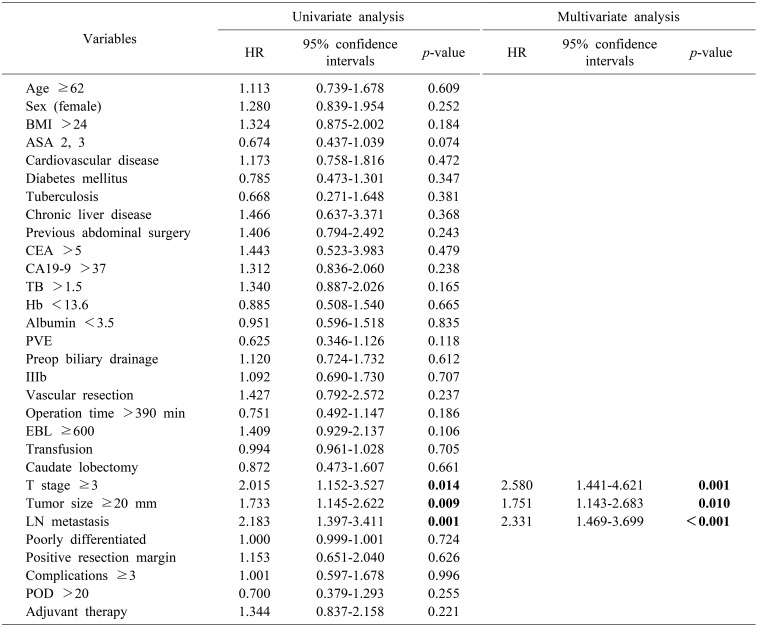

Similarly, advanced T stage ≥3 (HR: 2.015, p=0.014), tumor size ≥20 mm (HR: 1.733, p=0.009) and LN metastasis (HR: 2.183, p=0.001) were independent prognostic factors associated with recurrence on univariate analysis. By multivariate analysis, T stage ≥3 (HR: 2.580, CI: 1.441-4.621, p=0.001), tumor size ≥20 mm (HR: 1.751, CI: 1.143-2.683, p=0.010), and LN metastasis (HR: 2.331, CI: 1.469-3.699), p<0.001) were prognostic factors of recurrence (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors influencing recurrence.

Extended hepatectomy, which includes caudate lobectomy, is regarded as a standard procedure because in most cases, tumors are close to the caudate lobe B1.34,35,36,37,38,39,40 However, our study did not find significant differences in survival outcome or pattern of recurrence. In this study, the R0 rates were not significantly different following extended hepatectomy or simple hepatectomy, which might be the main reason for the results. Therefore, a clear caudate lobectomy is not necessary by preoperative imaging examination, R0 resection may be possible without caudate lobectomy.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study, so we depended on the completeness of medical records for our analysis. Second, all patients were from a single institution, which limits the generalizability of our results.

In conclusion, the results from this study suggested no difference in outcomes following surgery according to involved side. The main reason for the results appeared to be the lack of difference in the R0 rate between the two groups. Therefore, determining an optimal surgical plan through accurate image review is important to improve survival outcomes by raising the R0 resection rate on both sides.

References

- 1.Soares KC, Kamel I, Cosgrove DP, Herman JM, Pawlik TM. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: diagnosis, treatment options, and management. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3:18–34. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2014.02.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klatskin G. Adenocarcinoma of the hepatic duct at its bifurcation within the porta hepatis. An unusual tumor with distinctive clinical and pathological features. Am J Med. 1965;38:241–256. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(65)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:170–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tompkins RK, Thomas D, Wile A, Longmire WP., Jr Prognostic factors in bile duct carcinoma: analysis of 96 cases. Ann Surg. 1981;194:447–457. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198110000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumgart LH, Hadjis NS, Benjamin IS, Beazley R. Surgical approaches to cholangiocarcinoma at confluence of hepatic ducts. Lancet. 1984;1:66–70. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Abrams RA, Piantadosi S, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463–473. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seyama Y, Makuuchi M. Current surgical treatment for bile duct cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1505–1515. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i10.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Angelica MI, Jarnagin WR, Blumgart LH. Resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma: surgical treatment and long-term outcome. Surg Today. 2004;34:885–890. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2832-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aljiffry M, Walsh MJ, Molinari M. Advances in diagnosis, treatment and palliation of cholangiocarcinoma: 1990–2009. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4240–4262. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otto G. Diagnostic and surgical approaches in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valero V, 3rd, Cosgrove D, Herman JM, Pawlik TM. Management of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma in the era of multimodal therapy. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;6:481–495. doi: 10.1586/egh.12.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ratti F, Cipriani F, Piozzi G, Catena M, Paganelli M, Aldrighetti L. Comparative analysis of left- versus right-sided resection in klatskin tumor surgery: can lesion side be considered a prognostic factor? J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1324–1333. doi: 10.1007/s11605-015-2840-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seyama Y, Kubota K, Sano K, Noie T, Takayama T, Kosuge T, et al. Long-term outcome of extended hemihepatectomy for hilar bile duct cancer with no mortality and high survival rate. Ann Surg. 2003;238:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000074960.55004.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawasaki S, Imamura H, Kobayashi A, Noike T, Miwa S, Miyagawa S. Results of surgical resection for patients with hilar bile duct cancer: application of extended hepatectomy after biliary drainage and hemihepatic portal vein embolization. Ann Surg. 2003;238:84–92. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000074984.83031.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeyama T, Nagino M, Oda K, Ebata T, Nishio H, Nimura Y. Surgical approach to bismuth Type I and II hilar cholangiocarcinomas: audit of 54 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1052–1057. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318142d97e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagino M, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Sugawara G, Takahashi Y, et al. Evolution of surgical treatment for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: a single-center 34-year review of 574 consecutive resections. Ann Surg. 2013;258:129–140. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182708b57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konstadoulakis MM, Roayaie S, Gomatos IP, Labow D, Fiel MI, Miller CM, et al. Aggressive surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: is it justified? Audit of a single center's experience. Am J Surg. 2008;196:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirose T, Igami T, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Sugawara G, Mizuno T, et al. Surgical and radiological studies on the length of the hepatic ducts. World J Surg. 2015;39:2983–2989. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Natsume S, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Igami T, Sugawara G, Shimoyama Y, et al. Clinical significance of left trisectionectomy for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: an appraisal and comparison with left hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2012;255:754–762. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824a8d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosokawa I, Shimizu H, Yoshidome H, Ohtsuka M, Kato A, Yoshitomi H, et al. Surgical strategy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma of the left-side predominance: current role of left trisectionectomy. Ann Surg. 2014;259:1178–1185. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu H, Kimura F, Yoshidome H, Ohtsuka M, Kato A, Yoshitomi H, et al. Aggressive surgical resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma of the left-side predominance: radicality and safety of left-sided hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2010;251:281–286. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181be0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Launois B, Campion JP, Brissot P, Gosselin M. Carcinoma of the hepatic hilus. Surgical management and the case for resection. Ann Surg. 1979;190:151–157. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197908000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bengmark S, Ekberg H, Evander A, Klofver-Stahl B, Tranberg KG. Major liver resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1988;207:120–125. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198802000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boerma EJ. Research into the results of resection of hilar bile duct cancer. Surgery. 1990;108:572–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Launois B, Terblanche J, Lakehal M, Catheline JM, Bardaxoglou E, Landen S, et al. Proximal bile duct cancer: high resectability rate and 5-year survival. Ann Surg. 1999;230:266–275. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199908000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugiura Y, Nakamura S, Iida S, Hosoda Y, Ikeuchi S, Mori S, et al. Extensive resection of the bile ducts combined with liver resection for cancer of the main hepatic duct junction: a cooperative study of the Keio Bile Duct Cancer Study Group. Surgery. 1994;115:445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pichlmayr R, Weimann A, Klempnauer J, Oldhafer KJ, Maschek H, Tusch G, et al. Surgical treatment in proximal bile duct cancer. A single-center experience. Ann Surg. 1996;224:628–638. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199611000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, von Wasielewski R, Werner M, Weimann A, Pichlmayr R. Resectional surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:947–954. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagino M, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kanai M, Uesaka K, Hayakawa N, et al. Segmental liver resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuhaus P, Jonas S, Bechstein WO, Lohmann R, Radke C, Kling N, et al. Extended resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1999;230:808–818. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyazaki M, Ito H, Nakagawa K, Ambiru S, Shimizu H, Okaya T, et al. Parenchyma-preserving hepatectomy in the surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:575–583. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosuge T, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Makuuchi M. Improved surgical results for hilar cholangiocarcinoma with procedures including major hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 1999;230:663–671. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199911000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Gonen M, Burke EC, Bodniewicz BS J, et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507–517. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paik KY, Choi DW, Chung JC, Kang KT, Kim SB. Improved survival following right trisectionectomy with caudate lobectomy without operative mortality: surgical treatment for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1268–1274. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0503-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gazzaniga GM, Ciferri E, Bagarolo C, Filauro M, Bondanza G, Fazio S, et al. Primitive hepatic hilum neoplasm. J Surg Oncol Suppl. 1993;3:140–146. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930530537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsao JI, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Hayakawa N, Kondo S, Nagino M, et al. Management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of an American and a Japanese experience. Ann Surg. 2000;232:166–174. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fortner JG, Vitelli CE, Maclean BJ. Proximal extrahepatic bile duct tumors. Analysis of a series of 52 consecutive patients treated over a period of 13 years. Arch Surg. 1989;124:1275–1279. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410110029005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bismuth H, Nakache R, Diamond T. Management strategies in resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1992;215:31–38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199201000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lygidakis NJ, van der, Houthoff HJ. Surgical approaches to the management of primary biliary cholangiocarcinoma of the porta hepatis: the decision-making dilemma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1988;35:261–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee SG, Song GW, Hwang S, Ha TY, Moon DB, Jung DH, et al. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma in the new era: the Asan experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:476–489. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]