Abstract

Although cardiomyocyte terminal differentiation is nearly complete at birth in sheep, as in humans, very limited postnatal expansion of myocyte number may occur. The capacity of newborn cardiomyocytes to respond to growth stimulation by proliferation is poorly understood. Our objective was to test this growth response in newborn lambs with two stimuli shown to be potent inducers of cardiomyocyte growth in fetuses and adults: increased systolic load (Load) and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I). Vascular catheters and an inflatable aortic occluder were implanted in lambs. Hearts were collected for analysis at 18 days of age after a 7-day experiment and compared with control hearts. Load hearts, but not IGF-I hearts, were heavier (P = 0.001) because of increased mass of the left ventricle (LV), septum, and left atrium (40–50%, P = 0.004). Terminal differentiation and cell cycle activity were not different between groups. Myocyte length was 7% greater in Load lamb hearts (P < 0.05), and binucleated myocytes, which comprise ~90% of LV cells, were 25% larger in volume (P = 0.03). Myocyte number per gram of myocardium was decreased in all ventricles of Load lambs (P = 0.01). Cells from the IGF-I group were not different by any comparison. These results suggest that the newborn sheep LV responds to systolic stress with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, not proliferation. Furthermore, IGF-I is ineffective at stimulating cardiomyocyte proliferation at this age (despite effectiveness when administered before birth). Thus, to expand cardiomyocyte number in the newborn heart, therapies other than systolic pressure load and IGF-I treatment need to be developed.

Keywords: cardiac myocyte, congenital heart disease, hypertrophy, hyperplasia, insulin-like growth factor I

INTRODUCTION

Newborns with congenital cardiovascular anomalies face altered hemodynamic and hormonal cues guiding growth and development of their hearts. Immature hearts have different cardiac growth responses compared with mature hearts in response to similar alterations in hemodynamic load. These differences may be beneficial: left ventricular (LV) loading has been shown to have better outcomes when onset occurs in infancy rather than later in life (4, 16, 29). Despite the large number of infants born with congenital heart disease (CHD), there are few experimental studies to help us understand how cardiomyocyte growth is changed and, perhaps more importantly, the mechanisms that might underlie effective therapies.

Proliferation grows the immature heart, but expansion of cardiomyocyte number normally concludes at birth in humans and sheep (8, 9, 24). A small proportion of myocytes may remain capable of proliferating after birth, especially in the right ventricle (RV) (24). Arterial hypertension is a stimulus that before birth stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation, maturation, and cellular enlargement (5, 21, 39, 42). There is some evidence that arterial hypertension also stimulates proliferation after birth: neonatal pulmonary hypertension has been shown in one study to cause myocyte proliferation in the RV (26), and proliferation was found in atrial myocytes of very young infants with CHD (53). However, some evidence suggests that after birth the neonatal heart responds similarly to that of the adult, with hypertrophy instead of proliferation; grossly enlarged ventricular myocytes are found in newborns and infants affected by tetralogy of Fallot, ventricular septal defects, pulmonary stenosis, congenital aortic or mitral valvular disease, and other CHD (31). It is not known whether proliferative growth increases LV myocyte number after birth in infants with congenital left heart hypertension.

Surgical advances have enabled survival of many individuals affected by CHD, but this population continues to face increased rates of death from heart failure in young adulthood (50). Increasing cardiomyocyte number may reduce lifelong risk of heart failure in individuals affected by CHD (48). Insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) causes fetal cardiomyocyte proliferation without increasing maturation (45) and is therefore a candidate for therapeutic manipulation of cardiomyocyte number in the immature heart. To our knowledge, the action of IGF-I on neonatal cardiomyocytes in large mammals has not been studied, although IGF-I is a treatment for retinopathy of prematurity (25).

Fetal sheep are often used to model conditions of abnormal cardiac growth and development (6, 17). We used two well-established modalities of cardiac growth stimulation to test growth and maturation of cardiomyocytes in the newborn (5, 21, 26, 33, 39, 45). We hypothesized that systemic arterial hypertension would stimulate cardiomyocyte proliferation and cellular enlargement in the neonatal heart. To test this hypothesis, we created a model of aortic coarctation in the newborn lamb that increased systemic arterial pressure. We further hypothesized that IGF-I would stimulate cardiomyocyte proliferation in the neonatal heart. To test this hypothesis, we gave newborn lambs an IGF-I analog (LR3 IGF-I) with low IGF binding protein affinity (18).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Neonatal sheep were selected for this study because of the utility of comparing their cardiac growth to that achieved by fetal sheep in previous studies (5, 21, 45).

Surgery.

Twin lambs of normal birth weight (4.5 ± 0.1 kg), born spontaneously to mixed western breed ewes at 147 ± 0 days of gestation, were obtained from a local supplier. Two pregnancies thought to be twins were found to be triplets at birth and were reduced to twins before nursing. Sterile surgery was performed on all lambs at 7 days. Anesthesia was induced with intravenous ketamine (0.08 mg/kg) and diazepam (0.04 mg/kg). Lambs were intubated and mechanically ventilated. Anesthesia was maintained with 1–2% isoflurane in 100% oxygen. Pulse oximetry and rectal temperature were continuously monitored. Through an incision on the neck, polyvinyl catheters were placed in the aorta via the carotid artery (0.86-mm or 1.19-mm internal diameter; Scientific Commodities, Lake Havasu City, AZ) and in the superior vena cava via the jugular vein. A left lateral thoracotomy was performed, and an inflatable occluder (10–12 mm; In Vivo Metric, Healdsburg, CA) was placed around the aorta distal to the ligamentum arteriosum. Incisions were sutured closed in layers, air was evacuated from the chest, and catheters were tunneled under the skin to exit between the scapulae and secured in a pouch under elastic netting. After recovery from anesthesia, the lambs were returned to the ewe in a pen and were monitored until ambulating and nursing. Pain was controlled with subcutaneous meloxicam (0.2 mg/kg) after surgery and at 24 h. Lambs were allowed to recover for 4 days. Weight gain was uninterrupted by surgery and surgical recovery. All groups were the same age (11 days) on the initial day of the experiment (day 0).

Seven lambs were excluded from analysis: one received a pneumothorax and was euthanized in surgery, one died unexpectedly after surgery and was found to have a congenital cardiovascular defect, and five in the aortic occlusion group were euthanized midexperiment with signs of severe pulmonary hypertension. Lambs were pseudorandomized to assist equal distribution of sex ratios (male: female: Control 11:7, Load 10:5, IGF-I 4:4). The total number of lambs included in the study was 41.

Experimental protocol.

Lambs were acclimatized to rest quietly in a sling before study. Daily samples were taken for arterial chemistry. Plasma and serum for hormone assays were separated and frozen. Systemic pressures were measured with reference to a fluid-filled catheter affixed at the level of the right atrium. Heart rate was counted from the arterial waveform. IGF-I treatment consisted of twice-daily intravenous injection of LR3 IGF-I (GroPep, Adelaide, Australia). The dose of 0.15 mg·kg−1·day−1 was comparable to that previously found to increase heart weight by 30% over 1 wk in fetal sheep (45). Control and Load lambs received saline vehicle. Hypertension was induced by progressive daily inflation of the aortic occluder to increase mean aortic pressure by 14.5 ± 1.2 mmHg/day on days 0–4 and 7.2 ± 1.7 mmHg/day thereafter. The inflation of the aortic occluder was maintained constantly through the entire experimental period, but pressure regulatory mechanisms in the lamb led to a decline in mean arterial pressure by the following day, which necessitated occluder adjustments to simply maintain hypertension in the early phase of the experiment. Load tolerance was assessed by respiration, ambulation, and affect at the time of experiment and again after several hours. Occluders were placed but not inflated in the Control and IGF-I lambs.

Postmortem.

At the conclusion of the experiment, lambs were given intravenous heparin and euthanized with a commercial pentobarbital solution, which arrested the hearts in diastole. A midlateral section of the LV was excised and bisected, part frozen in liquid nitrogen and part fixed in zinc-buffered formalin. The ventricular wound edges were sealed with cyanoacrylate, and the hearts (n = 8 per group) were enzymatically digested as previously described (24). Briefly, coronaries were perfused through the aorta with a Tyrode solution to flush the blood out and then with a Tyrode solution containing 160 U/ml Worthington type II collagenase (Worthington Biochemicals, Lakewood, NJ) and 0.78 U/ml protease type XIV (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). A final perfusion with a calcium-free Kraftbrühe buffer rinsed out the enzymes. At the conclusion of the digestion, each ventricular wall was dissected from the heart, and myocytes were gently shaken free in separate vials of Kraftbrühe before fixation with 2% formaldehyde. Sampling and recovery of myocytes were similar between all groups and ventricular walls.

After the initial study, a second set of Control (n = 10) and Load (n = 7) lambs (included in total count above and in tables and figures) were studied to determine free wall weights for the purpose of calculating myocyte number. These lambs were treated exactly the same as the first set, except that at necropsy their hearts were excised and dissected along anatomical landmarks to obtain ventricular free wall weights.

Noncardiac tissues were taken to screen for pathological changes after LR3 IGF-I treatment (control n = 4, IGF-I n = 8). Adrenal, aortic, kidney, liver, lung, pancreatic, skeletal muscle, retinal, and thyroid tissues were fixed in 2% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned for staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Blood smears were dried and Giemsa stained. Slides were reviewed by a clinical pathologist. Pancreatic islets adjacent to the superior mesenteric artery were scored on a 1–3 scale, where 1 represented normal islet number and 3 represented many islets.

Cardiomyocyte measurements.

Cardiomyocyte morphometric measurements were made as previously described on isolated cardiomyocytes (21, 24). Length and width measurements were obtained from random, nonrepeating photomicrographs from at least 100 total cells per ventricular free wall per animal until at least 15 cardiomyocytes of each nucleation category were represented per sample. A shape factor, measured from no fewer than 10 myocytes of each nucleation category per ventricular free wall per animal, was used to calculate myocyte volume from length and width measurements (21, 24). Cardiomyocyte maturation was quantified by proportional representation of nucleation categories, as previously described (21, 24), by counting no fewer than 300 cardiomyocytes per ventricular wall per animal. Cell cycle activity was quantified by immunostaining for the nuclear protein Ki-67 (MIB-1; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) as previously described (21, 24). The presence or absence of staining was quantified in no fewer than 500 cells per ventricular wall per animal.

Cardiac histology.

Fixed sections that had been excised from ventricular walls before cardiomyocyte dissociation were embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections (5 µm) were stained with Masson’s trichrome. Photomicrographs were taken from two randomly sampled locations in each of LV endocardium, midwall, and epicardium. Unbiased point counting was performed to determine relative quantities of cardiomyocytes, blood vessels, collagen, and other connective tissue as previously described (22).

Cardiomyocyte number quantification.

The number of cardiomyocytes in each ventricular wall of each fetus was calculated as previously described (21, 24). The proportional relationship between ventricular wall weight and heart weight was derived from values measured from subgroups in which the hearts were dissected (Control, n = 10; Load, n = 7) and used to calculate ventricular wall weights from total heart weight for each fetus in which cardiomyocytes were enzymatically dissociated. Each ventricular wall weight was multiplied by the proportion of the myocardium that is composed of myocyte, calculated from histological measurements, and divided by the specific gravity of myocardium (1.05 g/ml), to yield the weight of the cardiomyocyte component of each ventricular wall. This was then divided by the average myocyte volume for that ventricular wall of that fetus, taking into account proportional representation of nucleation categories to yield myocyte number per wall.

Plasma and serum assays.

Cortisol was measured from serum, and IGF-I and insulin were measured from plasma, with no extraction. Angiotensin I (ANG I), the immediate precursor of the active hormone angiotensin II (ANG II), was column extracted from serum, lyophilized, and reconstituted before measurement. ANG I, cortisol, IGF-I, and insulin were measured by ELISA according to manufacturer’s protocol (Alpco, Salem, NH). Assay parameters were ANG I sensitivity 4.3 pg/ml, intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) 4.3%, interassay CV 7.4%; cortisol sensitivity 0.4 μg/dl, intra-assay CV 7.3%, interassay CV 7.6%; IGF-I sensitivity 0.091 ng/ml, intra-assay CV 5.1%, interassay CV 3.4%; insulin sensitivity 0.14 ng/ml, intra-assay CV 7.4%, interassay CV 4.9%.

Quantitative PCR.

Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR were carried out as previously described (15). Primers are listed in Table 1. Genes of interest were normalized to the geometric mean of the reference genes GAPDH, B2M, and RPL37A, none of which was altered by Load or IGF-I.

Table 1.

PCR primer sequences

| Gene | Sense | Antisense |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclin D1 (CCND1) | CTTCCTGTCGCTGGAGCCCG | AGCTTCTCGGCCGTCAGGGG |

| Cyclin D2 (CCND2) | TCCTCTCGCCATCAATTACC | GTCTCTTTGAGCTTGGACGC |

| Cyclin D3 (CCND3) | TGTGCAGAGGGAGATCAAGC | ACAGCTTCTCGATGGTCAGG |

| Cyclin B1 (CCNB1) | TGGGTCGTGAAGTCACTGGAAACA | CAGCATCTTCTTGGGCACACAGTT |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) | GAAGAGTTCTCCACAGGGACC | GGAATTCCAAAAGCTCTGGC |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) | CTGCCCATCAGCACCGTTCG | CTGGTGGGGGTGCCTTGTCC |

| Mitotic Arrest Deficient 2 (MAD2) | TCCAAGATGAAATCCGTTCAG | CCGACTCTTCCCATTTCTCA |

| Minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 (MCM6) | ACGTGCAGAAACTGATTCCC | TCTGTTCCTCATCTCGGAGC |

| Separase (ESPL1) | ATCAGGACGTTGTGAGGAGC | AGTCTTCCCCATCAGAACCC |

| Retinoblastoma protein (Rb1) | AAACTGCGCTTTGACATCG | CCCTGTTTGAGGTATCCACG |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21) | CTGCCCAAGCTCTACCTGC | CAAGTGGTCCTCCTGAGACG |

| Matrix metalloprotease 2 (MMP2) | ACCAGAGCACCATTGAGACC | GGTCACATCGCTCCAGACTT |

| Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1) | TTCATCTACACCCCTGCCAT | TCCTCACAACCAGCAGCATA |

| Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP2) | GCTGGACATTGGAGGAAAGA | GGAGGAGATGTAGCATGGGA |

| Hyaluronoglucosaminidase 2 (HYAL2) | AGGCCGCTGCCCTGATGTTG | GCGGCCGTGAGTGGAGGAAG |

| Collagen Type 1 alpha chain 1 (COL1A1) | GCAAGAACGGAGATGATGGT | CTCCATTTTCACCAGGGCTA |

| Collagen Type 3 alpha chain 1 (COL3A1) | TGGAAGAGATGGAAACCCTG | CTCACCAGTTTCGCCTTTGT |

| Collagen Type 4 alpha chain 2 (COL4A2) | CGGGTGTGAAGAAACTGGAC | GGAATCCCGAAACACCTCTT |

| Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) | GCTCCTCCGCCATCACCACG | CTGGGCTGCGTTGACCTCCC |

| Bone natriuretic peptide (BNP) | ACCTGTCGCTGCTAGGATGT | AGTCCCAGGTTTCTTCCAGG |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) | CTGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG | CAGTGGATGCAGGGATGATG |

| Beta-2-microglobulin (B2M) | ATCCAGCGTATTCCAGAG | GGGACAGAAGGTAGAAAG |

| Ribosomal protein L37a (RPL37A) | ACCAAGAAGGTCGGAATCGT | GGCACCACCAGCTACTGTTT |

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism (GraphPad, v6.0a, RRID:SCR_002798). Some values could not be collected from every lamb because of catheter failure, insufficient sample, etc. Sex distribution was tested by χ2-test. Daily physiological parameters were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. If data missing at random impeded repeated-measures analysis, missing values were imputed from the same animal on preceding and succeeding days (<1% of the values in Table 2). If indicated, multiple comparisons were performed with the Holm-Sidak correction, with Control as the reference group. Heart weights, body weights, myocardial histology, and mRNA expression levels were assessed by one-way ANOVA and myocyte parameters by two-way ANOVA. Outliers in PCR data were determined with the ROUT method based on the false discovery rate. Pancreatic pathology scores were compared by the Mann-Whitney test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Values are means ± SE.

Table 2.

Physiological parameters

| n | Day 0 | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 6 | Day 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial pressure, baseline, mmHg | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 84.1 ± 1.9 | 82.3 ± 1.9 | 83.4 ± 1.6 | 81.3 ± 1.2 | 82.4 ± 1.4 | 80.9 ± 1.4 | 80.6 ± 1.8 | 81.0 ± 1.7 |

| Load | 15 | 82.6 ± 1.7 | 86.6 ± 1.7 | 95.9 ± 2.5*† | 105.2 ± 3.2*† | 114.4 ± 4.4*† | 118.5 ± 4.8*† | 112.7 ± 4.9*† | 117.9 ± 4.7*† |

| IGF-I | 8 | 81.6 ± 1.8 | 81.8 ± 1.6 | 78.4 ± 1.8 | 79.6 ± 2.0 | 77.8 ± 1.8 | 78.2 ± 1.7 | 77.0 ± 1.4 | 76.6 ± 1.1 |

| Venous pressure, baseline, mmHg | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 2.6 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 2.6 ± 1.6 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 2.4 ± 1.9 |

| Load | 15 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 3.2 ± 2.0 | 4.5 ± 2.3* | 5.0 ± 1.7* | 4.9 ± 2.1* | 4.5 ± 1.9* | 5.2 ± 3.7* |

| IGF-I | 8 | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.8* | 3.6 ± 1.5 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 4.1 ± 1.0* | 3.3 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 1.4 |

| Heart rate, baseline, beats/min | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 214 ± 29 | 209 ± 24 | 202 ± 24 | 192 ± 23† | 197 ± 27† | 189 ± 21† | 187 ± 22† | 184 ± 28† |

| Load | 15 | 201 ± 26 | 196 ± 33 | 192 ± 28 | 192 ± 18 | 196 ± 18 | 187 ± 11 | 188 ± 26 | 186 ± 20 |

| IGF-I | 8 | 192 ± 21 | 188 ± 23 | 186 ± 27 | 185 ± 29 | 180 ± 30 | 177 ± 38 | 175 ± 31 | 173 ± 33 |

| pH, arterial | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.41 ± 0.00 | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 |

| Load | 14 | 7.39 ± 0.01 | 7.39 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 | 7.35 ± 0.03 | 7.38 ± 0.01 | 7.37 ± 0.02 | 7.38 ± 0.02 | 7.36 ± 0.02 |

| IGF-I | 8 | 7.40 ± 0.02 | 7.40 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 | 7.41 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 |

| , mmHg | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 40 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 |

| Load | 14 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 40 ± 2 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 2 | 41 ± 1 | 42 ± 2 |

| IGF-I | 8 | 40 ± 1 | 40 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 43 ± 1 |

| , mmHg | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 93 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 | 92 ± 2 | 89 ± 2 | 90 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 | 92 ± 3 |

| Load | 14 | 89 ± 1 | 90 ± 2 | 91 ± 2 | 95 ± 2 | 92 ± 1 | 87 ± 4 | 88 ± 2 | 86 ± 4 |

| IGF-I | 8 | 97 ± 4 | 89 ± 2† | 89 ± 4† | 87 ± 4† | 88 ± 4† | 83 ± 4† | 84 ± 5† | 86 ± 4† |

| Hemoglobin, arterial, g/dl | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 8.5 ± 0.3 | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 8.0 ± 0.3† | 7.7 ± 0.3† | 7.5 ± 0.2† | 7.3 ± 0.2† | 7.0 ± 0.2† | 6.8 ± 0.2† |

| Load | 14 | 8.3 ± 0.4 | 8.1 ± 0.4† | 7.8 ± 0.4† | 7.4 ± 0.5† | 7.5 ± 0.5† | 7.3 ± 0.5† | 7.2 ± 0.5† | 7.3 ± 0.5† |

| IGF-I | 8 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 8.2 ± 0.6 | 7.8 ± 0.7† | 7.7 ± 0.7† | 7.4 ± 0.7† | 7.1 ± 0.6† | 7.1 ± 0.7† | 6.9 ± 0.7† |

| Hematocrit, arterial, fraction | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.01† | 0.25 ± 0.01† | 0.24 ± 0.01† | 0.23 ± 0.01† | 0.22 ± 0.01† | 0.22 ± 0.01† | 0.21 ± 0.01† |

| Load | 14 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.01† | 0.24 ± 0.01† | 0.23 ± 0.01† | 0.24 ± 0.01† | 0.23 ± 0.01† | 0.23 ± 0.01† | 0.22 ± 0.02† |

| IGF-I | 8 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02† | 0.24 ± 0.02† | 0.23 ± 0.02† | 0.23 ± 0.02† | 0.21 ± 0.02† | 0.22 ± 0.02† | 0.21 ± 0.02† |

| O2 content, arterial, g/dl | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 11.0 ± 0.4† | 10.5 ± 0.3† | 10.1 ± 0.3† | 9.7 ± 0.4† | 8.8 ± 0.7† | 8.3 ± 0.7† | 8.9 ± 0.3† |

| Load | 14 | 10.9 ± 0.4 | 10.6 ± 0.5† | 10.2 ± 0.5† | 9.9 ± 0.5† | 9.8 ± 0.6† | 9.3 ± 0.7† | 9.3 ± 0.6† | 9.0 ± 0.8† |

| IGF-I | 8 | 11.6 ± 0.9 | 10.8 ± 0.9† | 10.4 ± 0.9† | 10.1 ± 0.9† | 9.7 ± 0.8† | 9.3 ± 0.9† | 9.1 ± 1.0† | 8.9 ± 0.9† |

| Glucose, arterial, mM | |||||||||

| Control | 15 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 6.7 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.3† |

| Load | 14 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 6.3 ± 0.3 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.2† |

| IGF-I | 8 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.3 | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 6.0 ± 0.3† |

Values are means ± SE for n lambs. IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor I; , arterial partial pressure of oxygen; , arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide. Different from

same-day Control and

within-group day 0 by 2-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Physiological parameters.

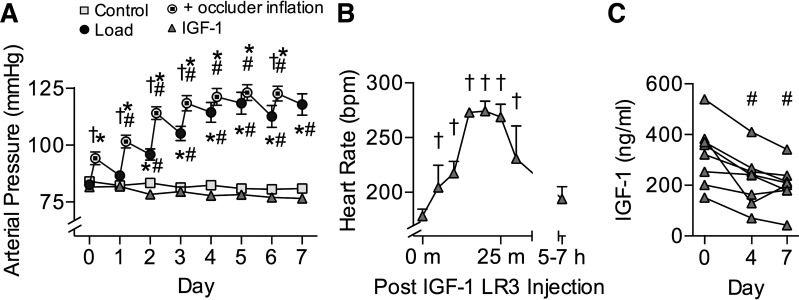

Sex distribution was not different between groups. All physiological parameters were similar between groups on the initial day of study (Table 2). Daily inflation of the aortic occluder increased arterial pressures in the Load group above baseline and above Control group pressures (Fig. 1A; P = 0.03). The interaction term between treatment and experimental day was significant for arterial pressure (P < 0.001); Load increased arterial pressure by day 2 and every day thereafter (P < 0.001) and was different from Control by day 2 (P = 0.002) and every day thereafter (P < 0.001). The interaction term was also significant for venous pressure (P < 0.001). Load increased venous pressure above day 0, and compared with Control, by day 3 and every day thereafter (P < 0.02 all comparisons). IGF-I increased venous pressures over Control on days 1 and 4 (P < 0.05). For heart rate the interaction term was not significant, but there was a main effect of experimental day (P < 0.001); heart rate in Control lambs decreased by day 3 and was lower than baseline every day thereafter (P = 0.03), consistent with an age-related decline after birth. Twice-daily LR3 IGF-I injection in the IGF-I group transiently elevated heart rate by 50% at 20 min after injection (representative data in Fig. 1B). Respiratory rate did not vary by group or day of treatment (54 ± 1 breaths/min).

Fig. 1.

Hemodynamic and hormone effects. A: in Load lambs (n = 15), an occluder encircling the aorta was pressurized each day to increase aortic pressures between 11 and 18 days of age (Control n = 15). Load baseline pressures were measured the next day before occluder adjustment. Arterial pressures were not different in insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) lambs (n = 8). B: there was a transient but profound rise in heart rate after each LR3 IGF-I injection. Shown is the first injection on the first day for a subset of animals (n = 3), representative of the response noted throughout the experiment. C: LR3 IGF-I treatment depressed endogenous IGF-I serum levels. Values are means ± SE or individual data points (C). Different from *same-day Control, #within-group day 0, or †within-group same-day baseline by 2-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Physiological anemia of the newborn decreased hemoglobin and hematocrit by ~20% in all lambs during the experiment period (Table 2). The interaction term between treatment and experimental day was significant for total hemoglobin (P = 0.04) but not hematocrit; total hemoglobin in all treatment groups decreased by day 1 (Load) or 2 (Control and IGF-I; P = 0.03) and remained low thereafter. There was a main effect of experimental day for hematocrit (P < 0.001); it was decreased by day 1 (P = 0.02) and remained low thereafter (P < 0.001). For arterial oxygen pressure (), the interaction term was significant (P = 0.02), and within the IGF-I group it decreased by day 1 and remained low thereafter (P < 0.05). The interaction term was not significant for oxygen content, but there was a main effect of experimental day (P < 0.001); it was decreased by day 1 and every day thereafter (P = 0.03). For arterial blood glucose the interaction term was not significant, but there was a main effect of experimental day (P = 0.0048); on day 7 it was less than on day 0 (P = 0.03). Arterial carbon dioxide pressure () was unaffected by treatment or experimental day.

At day 0, circulating endogenous IGF-I levels taken from indwelling arterial catheters in conscious, calm lambs were similar between groups (Fig. 1C). Treatment with LR3 IGF-I drove down endogenous IGF-I levels such that on days 4 and 7 circulating levels were depressed 50% from day 0 (Fig. 1C; P = 0.006). Nonfasting arterial insulin levels were not different between groups at any day (Table 3). The interaction term for arterial ANG I levels was significant (P = 0.01); levels were elevated more than twofold in conscious, calm lambs in the Load group compared with the Control group at day 7 (Table 3; P = 0.03). The interaction term for arterial cortisol levels was not significant, although cortisol levels were higher on the initial experimental day than on the last day (main effect, P = 0.015), and they had a tendency to be different by treatment group (P = 0.054).

Table 3.

Circulating hormones

|

Day 0 |

Day 7 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Load | IGF-I | Control | Load | IGF-I | |

| IGF-I, ng/ml | 322 ± 33 (7) | 376 ± 40 (8) | 323 ± 43 (8) | 347 ± 40 (7) | 360 ± 31 (8) | 201 ± 29* (8) |

| Insulin, ng/ml | 0.88 ± 0.26 (7) | 0.83 ± 0.19 (8) | 1.43 ± 0.36 (7) | 1.28 ± 0.40 (7) | 0.77 ± 0.28 (8) | 0.79 ± 0.24 (7) |

| Angiotensin I, pg/ml | 822 ± 303 (6) | 870 ± 174 (7) | 820 ± 189 (8) | 397 ± 114 (6) | 1,284 ± 389* (7) | 453 ± 79 (8) |

| Cortisol, ng/ml† | 247 ± 186 (6) | 249 ± 93 (7) | 121 ± 47 (8) | 116 ± 61 (6) | 180 ± 139 (7) | 89 ± 38 (8) |

Values are means ± SE for no. of lambs in parentheses. IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor I. Different from

same-day Control and

within-group day 7 vs. day 0, by 2-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Body and organ weights.

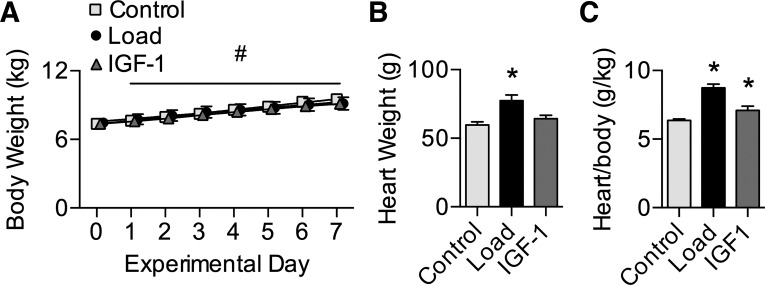

Groups were of similar body weight at study start (7.3 ± 0.2 kg), and all lambs had normal weight gain across the experimental period (3.2% per day; Fig. 2A). Consequently, groups were similar in weight on day 7 (9.2 ± 0.3 kg). Treatment affected heart weight (Fig. 2B; main effect P < 0.001); hearts were 18 g (30%) heavier in Load than Control lambs (P < 0.001). There was also a main effect of treatment on heart weight normalized to body weight (Fig. 2C; P < 0.001), which was 37% greater in Load than Control lambs (P < 0.001) and 11% greater in IGF-I than Control lambs (P = 0.04).

Fig. 2.

Body and heart weights. A: body weights from 11 to 18 days of age in Control (n = 18), Load (n = 15), and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I; n = 8) lambs. Load lambs experienced elevated systolic arterial pressures for 7 days; IGF-I lambs received 7 days of intravenous LR3 IGF-I. B and C: heart weights (B) and heart weights normalized to body weights (C) on the final experimental day (Control n = 18; Load n = 15; IGF-I n = 8). Values are means ± SE. Different from *Control or #within-group day 0 by 1- or 2-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Load increased the weight of the left atrium (51%; P values in Table 4), LV (40%), and septum (48%) compared with Control (Table 4). Consequently, free wall relative weights relative to heart weight were greater in Load than Control animals (left atrium 16%, LV 5%, septum 11%). Right atrium and RV weights were not different in Load vs. Control animals, and consequently relative weights were less than in Control animals (−17% and −12%, respectively).

Table 4.

Ventricular free wall weights

| Control (n = 10) | Load (n = 7) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left atrium, g | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 7.4 ± 0.6* | 0.002 |

| Relative to heart, g/g | 0.081 ± 0.004 | 0.093 ± 0.003* | 0.03 |

| Right atrium, g | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 0.39 |

| Relative to heart, g/g | 0.059 ± 0.002 | 0.049 ± 0.001* | 0.002 |

| Left ventricle, g | 20.5 ± 1.0 | 28.8 ± 2.5* | 0.004 |

| Relative to heart, g/g | 0.342 ± 0.005 | 0.360 ± 0.008* | 0.04 |

| Septum, g | 11.1 ± 0.6 | 16.3 ± 1.5* | 0.002 |

| Relative to heart, g/g | 0.184 ± 0.003 | 0.204 ± 0.004* | 0.002 |

| Right ventricle, g | 11.5 ± 0.7 | 13.4 ± 1.1 | 0.14 |

| Relative to heart, g/g | 0.190 ± 0.003 | 0.168 ± 0.002* | <0.001 |

Values are means ± SE for n lambs.

Different from Control by Student’s t-test (P < 0.05).

The majority (83%) of the LV myocardium comprised cardiomyocytes (Table 5), with the remainder being connective tissue (12%) and blood vessels (5%). There were no differences between groups.

Table 5.

LV histological fractional composition

| Control (n = 8) | Load (n = 8) | IGF-I (n = 8) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiomyocyte | 0.844 ± 0.017 | 0.832 ± 0.018 | 0.823 ± 0.013 |

| Other connective tissue | 0.082 ± 0.011 | 0.098 ± 0.010 | 0.086 ± 0.017 |

| Blood vessel | 0.047 ± 0.009 | 0.043 ± 0.009 | 0.056 ± 0.009 |

| Collagen | 0.027 ± 0.005 | 0.026 ± 0.007 | 0.033 ± 0.004 |

Values are means ± SE for n lambs. IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor; LV, left ventricle. Comparisons by 1-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Liver, kidney, and adrenal weights were similar between groups (data not shown). Liver weights relative to body weight for Control, Load, and IGF-I lambs were not significantly different (P = 0.08): 25 ± 1 g/kg, 25 ± 1 g/kg, and 22 ± 1 g/kg, respectively. Relative kidney weights for Control, Load, and IGF-I lambs were not significantly different (P = 0.09): 5.4 ± 0.2 g/kg, 6.1 ± 0.4 g/kg, and 6.1 ± 0.3 g/kg, respectively. Relative adrenal weights for Control, Load, and IGF-I lambs were not different: 0.12 ± 0.00 g/kg, 0.17 ± 0.02 g/kg, and 0.14 ± 0.01 g/kg, respectively.

Anatomical and histological features appeared normal after LR3 IGF-I treatment compared with Control animals for blood smears and adrenal, aortic, kidney, liver, lung, skeletal muscle, retinal, and thyroid tissues. LR3 IGF-I neonates tended to have more pancreatic islets than control animals (score range 1–3 vs. 1–2, mean = 2.1 ± 0.23 vs. 1.3 ± 0.3, median 2 vs. 1; P = 0.05).

Cardiomyocytes.

The interaction terms between ventricular origin of myocytes and treatment were not significant for any cardiomyocyte parameter (Table 6).

Table 6.

Cardiomyocyte parameter 2-way ANOVA P values

| Main Effects |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction | Treatment | Ventricle | |

| Mononucleated length | 0.884 | 0.017 | 0.245 |

| Mononucleated width | 0.853 | 0.290 | <0.001 |

| Mononucleated volume | 0.882 | 0.068 | 0.002 |

| Binucleated length | 0.784 | 0.017 | 0.987 |

| Binucleated width | 0.928 | 0.225 | <0.001 |

| Binucleated volume | 0.588 | 0.033 | 0.001 |

| Quadrinucleated length | 0.923 | 0.041 | 0.115 |

| Quadrinucleated width | 0.574 | 0.435 | 0.342 |

| Quadrinucleated volume | 0.649 | 0.113 | 0.442 |

| Mononucleation | 0.997 | 0.463 | <0.001 |

| Binucleation | 0.754 | 0.231 | <0.001 |

| Quadrinucleation | 0.547 | 0.855 | <0.001 |

| Cell cycle activity (unnormalized) | 0.932 | 0.002 | 0.594 |

| Cell cycle activity (per mononucleated) | 0.771 | 0.083 | 0.011 |

| Myocyte number | 0.873 | 0.788 | <0.001 |

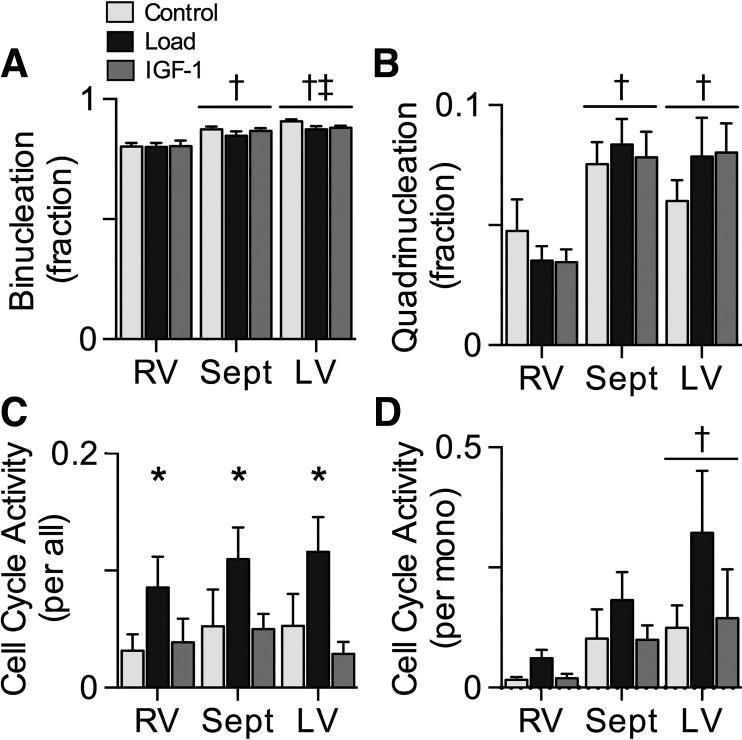

The majority of myocytes in the ventricular walls were terminally differentiated, as assessed by binucleation or quadrinucleation. There was a main effect of ventricle on mononucleation (data not shown); across all treatment groups, mononucleation was 172% higher in the RV than the septum (P < 0.001) and 298% higher in the RV than the LV (P < 0.001). There was a main effect of ventricle on binucleation (Fig. 3A); across all treatment groups, binucleation was 8% higher in the septum than RV (P < 0.001) and 11% higher in the LV than RV (P < 0.001), whereas LV was 3% higher than septum (P < 0.05). Quadrinucleation was also affected by ventricle (Fig. 3B); across all treatment groups, septum was 100% more quadrinucleated than RV (P < 0.001) and LV was 87% more than RV (P < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Cardiomyocyte terminal differentiation and cell cycle activity. A and B: maturation was assessed by the proportion of cardiomyocytes with binucleation (A) or quadrinucleation (B) in Control (n = 8), Load (n = 8), and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I; n = 8) lambs at 18 days of age. Load lambs experienced elevated systolic arterial pressures for 7 days; IGF-I lambs received 7 days of LR3 IGF-I. C: cell cycle activity was determined by Ki-67 immunostaining, expressed as % of all cardiomyocytes. D: cell cycle activity was also normalized to mononucleated myocytes, as those are the cells with proliferative potential. Values are means ± SE. Different from *Control, †RV, ‡septum by 2-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Very few cardiomyocytes were active in the cell cycle (Fig. 3C). Treatment affected cell cycle activity (main effect P = 0.002); across all ventricles, it was 126% higher in Load than Control (P = 0.007). As mononucleated myocytes are those cells that remain capable of proliferating, cell cycle activity was normalized per mononucleated myocyte (Fig. 3D). Normalized cell cycle activity was affected by ventricle; across all treatment groups, it was 515% higher in the LV than the RV (P = 0.008).

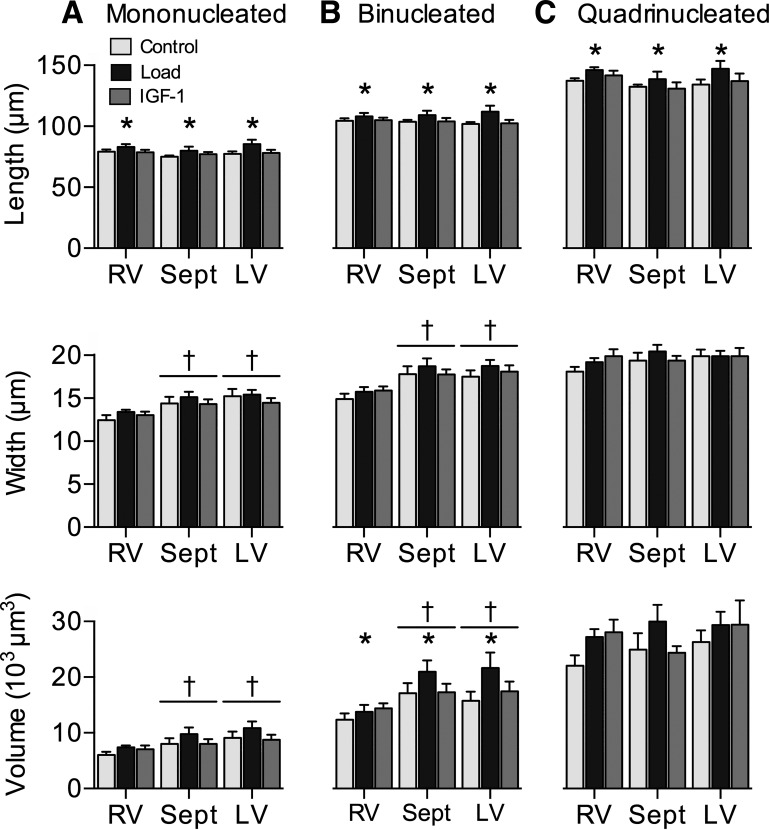

Treatment affected mononucleated length (Fig. 4A; main effect P = 0.02); Load increased it by 7% over Control (P = 0.02). Mononucleated length was not affected by ventricular origin (P = 0.245). Mononucleated width was not affected by treatment (P = 0.29). Mononucleated width was affected by ventricle (main effect P < 0.001); RV mononucleated width was 12% narrower than septum (P = 0.002) and 14% narrower than LV (P < 0.001). Mononucleated volume was not affected by treatment (P = 0.068). Mononucleated volume was affected by ventricle (main effect P = 0.002); RV mononucleated volume was 21% less than septum (P = 0.004) and 29% less than LV (P = 0.001). Treatment affected binucleated length (Fig. 4B; main effect P = 0.02); Load increased binucleated length 6% over Control (P = 0.02). Ventricular origin did not affect binucleated length (P = 0.987). Binucleated width was affected by ventricle (main effect P < 0.001); RV binucleated width was 17% narrower than septum (P < 0.001) and 15% narrower than LV (P < 0.001). Treatment did not affect binucleated width (P = 0.225). Binucleated volume was affected by both treatment and ventricle (main effect P = 0.03 and P < 0.001, respectively); Load increased binucleated volumes 25% over Control (P = 0.03); RV binucleated volumes were 27% less than septum volumes (P = 0.003) and 25% less than LV (P = 0.003). Treatment affected quadrinucleated length (Fig. 4C; main effect P = 0.04); Load increased quadrinucleated length 7% over Control (P = 0.03). Quadrinucleated length was not affected by ventricular origin P = 0.115). Quadrinucleated width was not affected by treatment (P = 0.435) or ventricle (P = 0.342), nor was quadrinucleated volume (P = 0.113 and P = 0.442, respectively). There were no significant differences in myocyte dimensions associated with the IGF-I treatment.

Fig. 4.

Cardiomyocyte size: mononucleated (mono) cardiomyocyte length, width, and volume (A), binucleate (bi) length, width, and volume (B), and quadrinucleate (quad) length, width, and volume (C) in Control (n = 8), Load (n = 8), and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I; n = 8) lambs at 18 days of age. Load lambs experienced elevated systolic arterial pressures for 7 days; IGF-I lambs received 7 days of LR3 IGF-I. Values are means ± SE. Different from *Control or †RV by 2-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

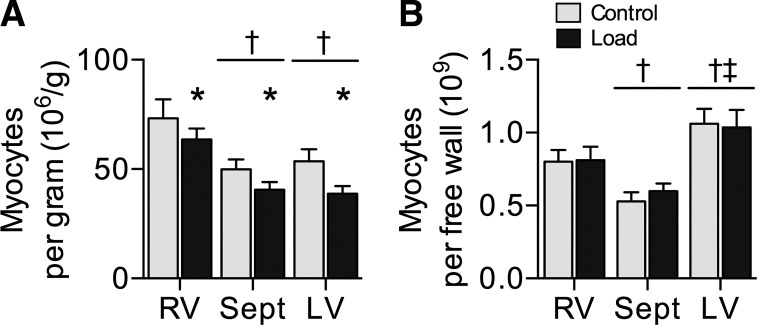

Cardiomyocyte number was calculated per gram of tissue (Fig. 5A) and per ventricular free wall (Fig. 5B) for Control and Load hearts. Cell number per gram was affected by treatment (main effect P = 0.01) and ventricle (P < 0.001). Load decreased cell number per gram 19% below Control (P = 0.01). Myocyte number per gram was 51% more in RV than septum (P < 0.001) and 48% more in RV than LV (P < 0.001). Cardiomyocyte number per ventricular free wall was not affected by group but was affected by ventricle (main effect P < 0.001). Myocyte number per RV wall was 43% more than per septum (P = 0.02) and 24% less than per LV (P = 0.02), whereas myocyte number per septum was 46% less than per LV (P < 0.001).

Fig. 5.

Cardiomyocyte number: cardiomyocyte number per gram of myocardium (A) and myocyte number per ventricular free wall (B) in Control (n = 8) and Load (n = 8) lambs at 18 days of age. Load lambs experienced elevated systolic arterial pressures for 7 days. Values are means ± SE. Different from *Control, †RV, ‡septum by 2-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

mRNA expression levels.

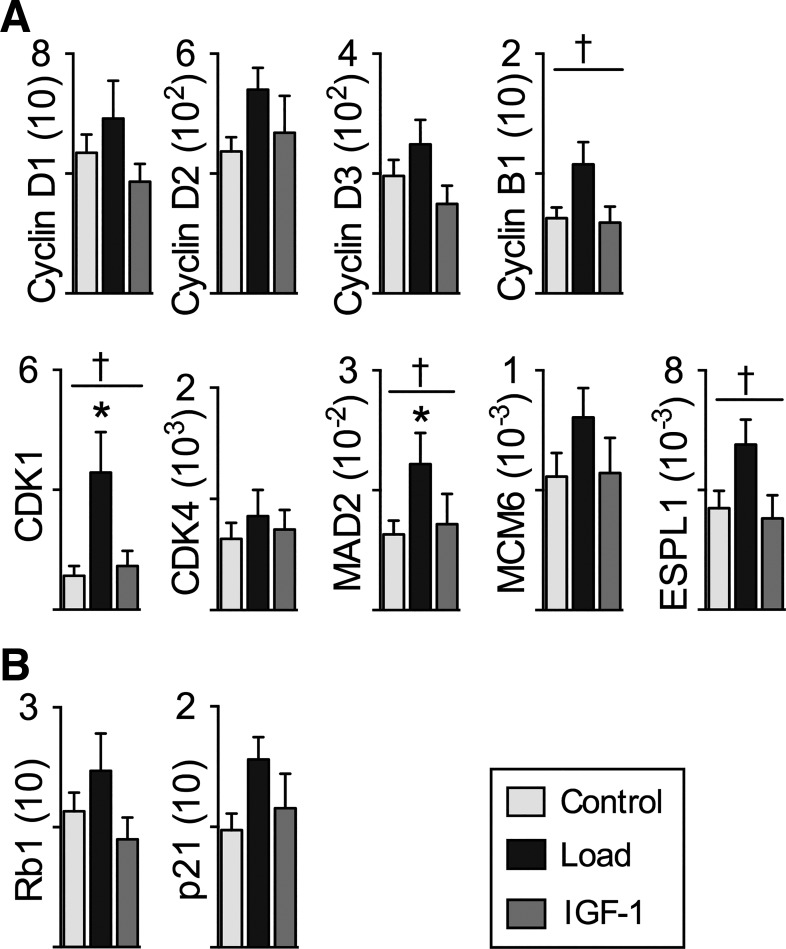

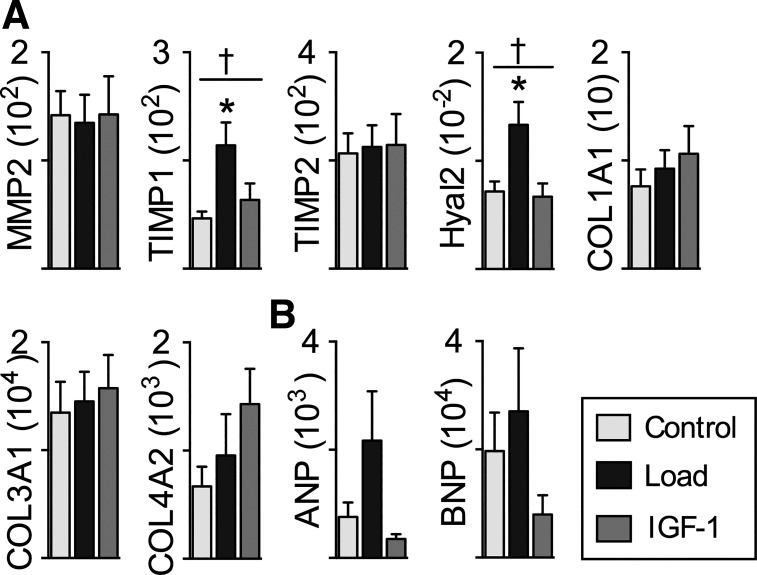

We used quantitative PCR to determine LV mRNA expression levels of genes involved in cell cycle progression (Fig. 6A), inhibition of cell cycle progression (Fig. 6B), and extracellular matrix remodeling (Fig. 7A) and indicative of cardiac stress (Fig. 7B). Within the genes involved in cell cycle progression, treatment affected mRNA expression of cyclin B1 (P = 0.04), CDK1 (P = 0.02) MAD2 (P = 0.02), and ESPL1 (P = 0.007). By pairwise analysis, mRNA was more abundant in Load than Control for CDK1 by 300% (P = 0.02) and MAD2 by 93% (P < 0.05) and tended to be 72% greater for cyclin B1 (P = 0.07) and 63% greater for ESPL1 (P = 0.05). Treatment did not affect mRNA expression of cyclin D1 (P = 0.252), cyclin D2 (P = 0.251), cyclin D3 (P = 0.127), cdk4 (P = 0.751), MCM6 (P = 0.306), Rb1 (P = 0.229), or p21 (P = 0.16).

Fig. 6.

Left ventricle (LV) cell cycle regulator mRNA expression: genes that promote cell cycle progression (A) and genes that inhibit cell cycle progression (B) in Control (n = 8), Load (n = 8), and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I; n = 8) lambs at 18 days of age. mRNA levels of experimental genes were normalized to the geometric mean of the reference genes GAPDH, B2M, and RPL37A, none of which was altered by Load or IGF-I. Full gene names are given in Table 1. Load lambs experienced elevated systolic arterial pressures for 7 days; IGF-I lambs received 7 days of LR3 IGF-I. Values are means ± SE. †Significantly affected by treatment, *different from Control by 1-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Left ventricle (LV) extracellular matrix and peptide mRNA expression: genes regulating extracellular matrix (A) and natriuretic peptides (B) indicative of cardiac stress in Control (n = 8), Load (n = 8), and insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I; n = 8) lambs at 18 days of age. mRNA levels of experimental genes were normalized to the geometric mean of the reference genes GAPDH, B2M, and RPL37A, none of which was altered by Load or IGF-I. Load lambs experienced elevated systolic arterial pressures for 7 days; IGF-I lambs received 7 days of LR3 IGF-I. Values are means ± SE. †Significantly affected by treatment, *different from Control by 1-way ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Within genes involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, treatment affected mRNA expression of Hyal2 (P = 0.009), and TIMP1 (P = 0.01). By pairwise analysis, mRNA was more abundant in Load than Control for Hyal2 by 86% (P = 0.02) and TIMP1 by 144% (P = 0.01). Treatment did not affect mRNA expression of MMP2 (P = 0.98), TIMP2 (P = 0.965), COL1A1 (P = 0.571), COL3A1 (P = 0.854), or COL4A2 (P = 0.238). Within genes indicative of cardiac stress, treatment tended to affect mRNA expression of ANP (P = 0.07) but not BNP (P = 0.278).

DISCUSSION

Young hearts have greater plasticity in their response to cardiac stress than older hearts (16, 35, 44), in part because of the potential of immature cardiomyocytes to grow by proliferation (23). In this study we show in young lambs that LV outflow obstruction stimulates a response similar to that seen in the adult heart, with cardiomyocyte enlargement to increase heart mass but without myocyte proliferation. The increased cell cycle activity in lambs with arterial hypertension, and increased expression of cell cycle and extracellular matrix regulators, appears antithetical to the unchanged myocyte number but has precedent in pathological cardiac hypertrophy in the adult (54). We further show that at this young age IGF-I stimulates neither the proliferation found in near-term fetuses (45) nor the cellular enlargement found in adult cardiomyocytes (19, 30).

Adaptation to hypertension.

Despite the large number of infants born with cardiac hemodynamics altered because of CHD, few experimental studies have been conducted to understand how cardiomyocyte growth is regulated in newborn large mammals. There is conflicting evidence as to whether cellular hypertrophy or proliferation contributes to increased RV growth following pulmonary artery banding (1, 26). It should be noted that those authors concluded that proliferation had occurred on the basis of increased nuclear expression of Ki-67; however, we determined that increased cell cycle activity, which we also found (at similarly low rates), was not supporting cardiomyocyte proliferation, as the number of cells was not increased. We found that increased LV mass resulted from myocyte hypertrophy. As binucleated cells comprise the majority of myocytes in the neonatal heart, the expanded volume of LV binucleated myocytes was the greatest contributor to increased cardiac mass in the Load neonates. This type of growth is similar to that seen in adults, in whom arterial hypertension causes cardiac hypertrophy via cellular enlargement (30, 38). Our finding is supported by cardiac biopsies showing myocyte hypertrophy in children with CHD from 0 to 15 yr, compared with normally growing children (31).

It is notable that long-term survival increases with surgical correction of coarctation of the aorta at younger ages, thus the recommendation to operate in the first year of life (14, 52) and before the gradient across the narrowing is >20 mmHg (52). This suggests more pronounced adverse remodeling at older ages. Interestingly, “myocardial retraining” by pulmonary artery banding, to prepare the LV for systemic pressures before arterial switch operation, has better outcomes when the banding occurs before 3 mo of age (29). As this study shows that cardiomyocyte proliferation is not involved in the neonatal response to increased LV load at 1 wk, the better performance of hearts when they are loaded at younger ages may be a function of coronary growth (4, 16), a more adaptive fibrotic response, or epigenetic modifications. It may take longer than 1 wk for those changes to manifest, however, as we did not see any difference in coronary vessels or connective tissue by histological morphometry.

In support of this possibility, we identified two matrix-regulating genes that increased mRNA expression in Load hearts, TIMP1 and Hyal2. TIMP1 is consistently increased in fibrotic hearts, and increased levels in the Load group may be an early sign of fibrosis (46) or may be indicative of extracellular matrix remodeling to accommodate myocyte enlargement. Hyal2 degrades hyaluronan, an essential matrix protein during embryonic cardiac development (10), an excess of which predisposes to heart failure (13). These differences in gene expression may be indicative of future adaptive or maladaptive changes in response to cardiac stress, as both involve remodeling of extracellular matrix (27).

Myocyte volume is proportional to the second power of the radius but only the first power of the length. Statistically significant differences in length account for 36% of the greater volume of LV binucleated myocytes in Load lambs, whereas statistically insignificant differences in width account for 55% of the difference. Clearly, myocyte width is an important factor despite a nonstatistical finding in this study. Indeed, wider myocytes were reported in infants affected by CHD (length was not measured) (31). Myocyte thickening is associated with concentric ventricular hypertrophy and normalization of increased wall stress due to hypertension in adults (11). That we found an increase in length but not width, in contrast to the growth seen in adult cardiomyocytes, perhaps reflects an immaturity of the rapidly enlarging neonatal heart. We suggest that, as in the fetus (21), myocyte thickening might secondarily be found with a longer period of neonatal hypertension.

Cell cycle activation does not occur in normal postnatal hypertrophic cardiac growth but does in pathological hypertrophy of the adult heart (54). Reactivation of the cell cycle activity without cardiomyocyte proliferation suggests that the systemic arterial hypertension in this study was perhaps stimulating a pathological response in the neonatal heart. However, the role of cell cycle regulators in physiological adaptation to arterial hypertension in the neonatal heart is unknown. Progression regulators cyclins D1, D2, and D3, as well as cyclin B and CDK4, all decrease in expression between the fetal, neonatal, and adult heart (3). In contrast, p21 and Rb1, which inhibit cell cycle progression, increase from fetal to neonatal to adult heart. The cyclin B-CDK1 complex is important for progression from G2 to mitosis, and in the Load LV we found upregulated CDK1 and a tendency for increased cyclin B1 expression. Further investigation found upregulation in Load hearts of the spindle checkpoint gene MAD2, important for chromosomal segregation (49), and ESLP1, important for proteolytic cleavage to allow separation of sister chromatids (37). These changes are in concordance with the tendency for increased cell cycle activity in the LV of Load neonates, despite evidence that there was neither increased cardiomyocyte number nor increased nucleation (in which karyokinesis without cytokinesis occurs). It is possible that cell cycle activity supported DNA replication leading to myocyte nuclear polyploidy, indicative of cardiac maturation and pathological hypertrophy (2, 7). It should be noted that the mRNA expression level analysis was conducted in response to the myocyte growth findings, to help understand and interpret them, but these analyses may be underpowered, with consequent possibility of false negative findings.

It is notable that, although we created a model of the physiology of congenital left-sided heart obstruction (12), RV myocytes underwent a myocyte hypertrophy similar to those in the LV and septum. This may have been stimulated by hemodynamic load, as venous pressure was elevated. We also found activation of the renin-angiotensin system in Load lambs, which is not surprising because the position of the aortic occluder would reduce kidney perfusion pressure. ANG II causes hypertrophic cardiac remodeling in adults (47) and hypertrophic growth secondary to its effects on blood pressure in the fetus (32, 41). ANG II also has a direct proliferative effect in fetal myocytes (45), although in utero this effect is not powerful enough to substantially increase ventricular mass (40). Whether ANG II regulated cardiomyocyte growth in the hypertensive neonate is unknown.

Response to IGF-I.

In adults, IGF-I signaling is intrinsic to “adaptive” or “physiological” cardiac hypertrophy by cellular enlargement, for example, as occurs in exercise (30, 34). Although there may be an IGF receptor (IGFR)2-mediated hypertrophic effect (28, 51), fetal IGF-I infusion causes abundant cardiomyocyte proliferation (45). Until now, the evidence has suggested that IGF-I may be a viable therapy to aid cardiomyocyte proliferation in neonates. Unexpectedly, IGF-I resulted in neither proliferative nor hypertrophic cardiomyocyte growth in neonatal lambs in this study. It is clear that LR3 IGF-I was biologically active within the neonates: heart rate was profoundly but transiently elevated at 20 min after administration, as occurs in fetuses. Venous pressures tended to be higher in the IGF-I group; we believe this is most likely due to biological variation in a parameter that is technically challenging to measure (because of animal posture and movement) rather than a response to the IGF-I infusion. In addition to the effect on heart rate, circulating levels of endogenous IGF-I decreased, indicating feedback on IGF-I production. We studied an additional four lambs to determine whether there was evidence for a proliferative response immediately after birth and found that LR3 IGF-I treatment from 2 to 8 days of age did not affect heart weight (Control 6.7 ± 0.5 g/kg; IGF-I 6.9 ± 0.0 g/kg). Consequently, we suggest that this shift in cardiomyocyte response to IGF-I occurs immediately before, or at, birth.

We speculate that cardiac maturation associated with parturition temporarily disrupts IGF-I signaling in cardiomyocytes. IGF-I resistance in tissues that are usually sensitive has been described previously (20). In some cases, IGF-I resistance is associated with decreased expression of IGFR1. However, IGFR1 mRNA is not different at 7 postnatal days compared with the last half of gestation (36). IGF-I resistance may result from high levels of tumor necrosis factor (20), which increase at parturition (43). Regardless of mechanism, the failure of neonatal cardiomyocytes to proliferate or enlarge in response to exogenous IGF-I indicates that IGF-I is a poor therapeutic candidate for increasing cardiomyocyte number or aiding in “physiological” hypertrophy in the neonatal heart.

Perspectives and Significance

The critical findings of this study are that the ventricles of the neonatal large mammal respond to LV systolic stress with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy rather than proliferation and that IGF-I is ineffective at stimulating cardiomyocyte proliferation at this age. Our hypotheses were suggested by cardiac growth regulation in the near-term fetus, but our findings demonstrate the profound differences of the neonatal heart from the fetal heart, although only weeks separate them. Consequently, extrapolation from the fetus or the adult is not appropriate to guide therapy for the newborn. Knowledge about how hemodynamic stress regulates cardiac growth in the newborn is essential to new approaches to reducing the progression toward heart failure currently experienced by many individuals with corrected congenital cardiac defects. The finding of IGF-I resistance in the neonatal heart is important, given that, until now, studies have suggested it as a good candidate to expand perinatal cardiomyocyte number. Further studies are required to determine the mechanism of IGF-I resistance, and develop alternative interventions to increase cardiomyocyte number in the neonatal period, or to develop protocols for in utero IGF-I therapy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grants P01 HD-034430 and R01 HD-071068 and by the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S.J. conceived and designed research; A.N.W., G.D.G., S.L., T.K.M., N.G., and S.S.J. performed experiments; A.N.W. and S.S.J. analyzed data; A.N.W. and S.S.J. interpreted results of experiments; S.S.J. prepared figures; A.N.W. and S.S.J. drafted manuscript; A.N.W., G.D.G., S.L., T.K.M., N.G., and S.S.J. edited and revised manuscript; A.N.W., G.D.G., S.L., T.K.M., N.G., and S.S.J. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Loni Socha and H. Mike Espinoza for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abduch MC, Assad RS, Rodriguez MQ, Valente AS, Andrade JL, Demarchi LM, Marcial MB, Aiello VD. Reversible pulmonary trunk banding III: assessment of myocardial adaptive mechanisms—contribution of cell proliferation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 133: 1510–1516, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler CP. Relationship between deoxyribonucleic acid content and nucleoli in human heart muscle cells and estimation of cell number during cardiac growth and hyperfunction. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab 8: 373–386, 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahuja P, Sdek P, MacLellan WR. Cardiac myocyte cell cycle control in development, disease, and regeneration. Physiol Rev 87: 521–544, 2007. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoyagi T, Mirsky I, Flanagan MF, Currier JJ, Colan SD, Fujii AM. Myocardial function in immature and mature sheep with pressure-overload hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 262: H1036–H1048, 1992. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.4.H1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbera A, Giraud GD, Reller MD, Maylie J, Morton MJ, Thornburg KL. Right ventricular systolic pressure load alters myocyte maturation in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R1157–R1164, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.4.R1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barry JS, Anthony RV. The pregnant sheep as a model for human pregnancy. Theriogenology 69: 55–67, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bensley JG, Stacy VK, De Matteo R, Harding R, Black MJ. Cardiac remodelling as a result of pre-term birth: implications for future cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J 31: 2058–2066, 2010. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Felker A, Salehpour M, Alkass K, Bernard S, Sjostrom SL, Szewczykowska M, Jackowska T, Dos Remedios C, Malm T, Andrä M, Jashari R, Nyengaard JR, Possnert G, Jovinge S, Druid H, Frisén J. Dynamics of cell generation and turnover in the human heart. Cell 161: 1566–1575, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burrell JH, Boyn AM, Kumarasamy V, Hsieh A, Head SI, Lumbers ER. Growth and maturation of cardiac myocytes in fetal sheep in the second half of gestation. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 274: 952–961, 2003. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camenisch TD, Spicer AP, Brehm-Gibson T, Biesterfeldt J, Augustine ML, Calabro A Jr, Kubalak S, Klewer SE, McDonald JA. Disruption of hyaluronan synthase-2 abrogates normal cardiac morphogenesis and hyaluronan-mediated transformation of epithelium to mesenchyme. J Clin Invest 106: 349–360, 2000. doi: 10.1172/JCI10272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carabello BA. Concentric versus eccentric remodeling. J Card Fail 8, Suppl: S258–S263, 2002. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr M, Curtis S, Marek J. Congenital left-sided heart obstruction. Echo Res Pract 2018: ERP-18-0016, 2018. doi: 10.1530/ERP-18-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhury B, Xiang B, Liu M, Hemming R, Dolinsky VW, Triggs-Raine B. Hyaluronidase 2 deficiency causes increased mesenchymal cells, congenital heart defects, and heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 10: e001598, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen M, Fuster V, Steele PM, Driscoll D, McGoon DC. Coarctation of the aorta. Long-term follow-up and prediction of outcome after surgical correction. Circulation 80: 840–845, 1989. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.80.4.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis L, Musso J, Soman D, Louey S, Nelson JW, Jonker SS. Role of adenosine signaling in coordinating cardiomyocyte function and coronary vascular growth in chronic fetal anemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 315: R500–R508, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00319.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flanagan MF, Aoyagi T, Currier JJ, Colan SD, Fujii AM. Effect of young age on coronary adaptations to left ventricular pressure overload hypertrophy in sheep. J Am Coll Cardiol 24: 1786–1796, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowden AL. The insulin-like growth factors and feto-placental growth. Placenta 24: 803–812, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4004(03)00080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis GL, Ross M, Ballard FJ, Milner SJ, Senn C, McNeil KA, Wallace JC, King R, Wells JR. Novel recombinant fusion protein analogues of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I indicate the relative importance of IGF-binding protein and receptor binding for enhanced biological potency. J Mol Endocrinol 8: 213–223, 1992. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0080213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CY, Hao LY, Buetow DE. Insulin-like growth factor-induced hypertrophy of cultured adult rat cardiomyocytes is L-type calcium-channel-dependent. Mol Cell Biochem 231: 51–59, 2002. doi: 10.1023/A:1014432923220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain S, Golde DW, Bailey R, Geffner ME. Insulin-like growth factor-I resistance. Endocr Rev 19: 625–646, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonker SS, Faber JJ, Anderson DF, Thornburg KL, Louey S, Giraud GD. Sequential growth of fetal sheep cardiac myocytes in response to simultaneous arterial and venous hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R913–R919, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00484.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonker SS, Giraud MK, Giraud GD, Chattergoon NN, Louey S, Davis LE, Faber JJ, Thornburg KL. Cardiomyocyte enlargement, proliferation and maturation during chronic fetal anaemia in sheep. Exp Physiol 95: 131–139, 2010. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.049379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonker SS, Louey S. Endocrine and other physiologic modulators of perinatal cardiomyocyte endowment. J Endocrinol 228: R1–R18, 2016. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonker SS, Louey S, Giraud GD, Thornburg KL, Faber JJ. Timing of cardiomyocyte growth, maturation, and attrition in perinatal sheep. FASEB J 29: 4346–4357, 2015. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-272013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kistner A, Sigurdsson J, Niklasson A, Löfqvist C, Hall K, Hellström A. Neonatal IGF-1/IGFBP-1 axis and retinopathy of prematurity are associated with increased blood pressure in preterm children. Acta Paediatr 103: 149–156, 2014. doi: 10.1111/apa.12478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leeuwenburgh BP, Helbing WA, Wenink AC, Steendijk P, de Jong R, Dreef EJ, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Baan J, van der Laarse A. Chronic right ventricular pressure overload results in a hyperplastic rather than a hypertrophic myocardial response. J Anat 212: 286–294, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li AH, Liu PP, Villarreal FJ, Garcia RA. Dynamic changes in myocardial matrix and relevance to disease: translational perspectives. Circ Res 114: 916–927, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lumbers ER, Kim MY, Burrell JH, Kumarasamy V, Boyce AC, Gibson KJ, Gatford KL, Owens JA. Effects of intrafetal IGF-I on growth of cardiac myocytes in late-gestation fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E513–E519, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90497.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma K, Hua Z, Yang K, Hu S, Lacour-Gayet F, Yan J, Zhang H, Pan X, Chen Q, Li S. Arterial switch for transposed great vessels with intact ventricular septum beyond one month of age. Ann Thorac Surg 97: 189–195, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maillet M, van Berlo JH, Molkentin JD. Molecular basis of physiological heart growth: fundamental concepts and new players. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14: 38–48, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nrm3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishikawa T, Sekiguchi M, Takao A, Ando M, Hiroe M, Morimoto S, Kasajima T. Histopathological assessment of endomyocardial biopsy in children: I. Semiquantitative study on the hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol 3: 5–11, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norris AW, Bahr TM, Scholz TD, Peterson ES, Volk KA, Segar JL. Angiotensin II-induced cardiovascular load regulates cardiac remodeling and related gene expression in late-gestation fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 75: 689–696, 2014. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olson AK, Protheroe KN, Segar JL, Scholz TD. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and regulation in the pressure-loaded fetal ovine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1587–H1595, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00984.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platt C, Houstis N, Rosenzweig A. Using exercise to measure and modify cardiac function. Cell Metab 21: 227–236, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakusan K, Flanagan MF, Geva T, Southern J, Van Praagh R. Morphometry of human coronary capillaries during normal growth and the effect of age in left ventricular pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation 86: 38–46, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.86.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reini SA, Wood CE, Keller-Wood M. The ontogeny of genes related to ovine fetal cardiac growth. Gene Expr Patterns 9: 122–128, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruppenthal S, Kleiner H, Nolte F, Fabarius A, Hofmann WK, Nowak D, Seifarth W. Increased separase activity and occurrence of centrosome aberrations concur with transformation of MDS. PLoS One 13: e0191734, 2018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sadoshima J, Izumo S. The cellular and molecular response of cardiac myocytes to mechanical stress. Annu Rev Physiol 59: 551–571, 1997. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Samson F, Bonnet N, Heimburger M, Rücker-Martin C, Levitsky DO, Mazmanian GM, Mercadier JJ, Serraf A. Left ventricular alterations in a model of fetal left ventricular overload. Pediatr Res 48: 43–49, 2000. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandgren J, Scholz TD, Segar JL. ANG II modulation of cardiac growth and remodeling in immature fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 308: R965–R972, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00034.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segar JL, Dalshaug GB, Bedell KA, Smith OM, Scholz TD. Angiotensin II in cardiac pressure-overload hypertrophy in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R2037–R2047, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.6.R2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segar JL, Volk KA, Lipman MH, Scholz TD. Thyroid hormone is required for growth adaptation to pressure load in the ovine fetal heart. Exp Physiol 98: 722–733, 2013. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.069435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seghaye MC, Heyl W, Grabitz RG, Schumacher K, von Bernuth G, Rath W, Duchateau J. The production of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in neonates assessed by stimulated whole cord blood culture and by plasma levels at birth. Biol Neonate 73: 220–227, 1998. doi: 10.1159/000013980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spirito P, Maron BJ. Relation between extent of left ventricular hypertrophy and age in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 13: 820–823, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sundgren NC, Giraud GD, Schultz JM, Lasarev MR, Stork PJ, Thornburg KL. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphoinositol-3 kinase mediate IGF-1 induced proliferation of fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R1481–R1489, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00232.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takawale A, Zhang P, Patel VB, Wang X, Oudit G, Kassiri Z. Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 promotes myocardial fibrosis by mediating CD63-integrin β1 interaction. Hypertension 69: 1092–1103, 2017. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tham YK, Bernardo BC, Ooi JY, Weeks KL, McMullen JR. Pathophysiology of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure: signaling pathways and novel therapeutic targets. Arch Toxicol 89: 1401–1438, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsilimigras DI, Oikonomou EK, Moris D, Schizas D, Economopoulos KP, Mylonas KS. Stem cell therapy for congenital heart disease: a systematic review. Circulation 136: 2373–2385, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vader G, Musacchio A. HORMA domains at the heart of meiotic chromosome dynamics. Dev Cell 31: 389–391, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verheugt CL, Uiterwaal CS, van der Velde ET, Meijboom FJ, Pieper PG, van Dijk AP, Vliegen HW, Grobbee DE, Mulder BJ. Mortality in adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J 31: 1220–1229, 2010. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang KC, Brooks DA, Botting KJ, Morrison JL. IGF-2R-mediated signaling results in hypertrophy of cultured cardiomyocytes from fetal sheep. Biol Reprod 86: 183, 2012. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.100388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, del Nido P, Fasules JW, Graham TP Jr, Hijazi ZM, Hunt SA, King ME, Landzberg MJ, Miner PD, Radford MJ, Walsh EP, Webb GD. ACC/AHA 2008 Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Congenital Heart Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines on the management of adults with congenital heart disease). Circulation 118: e714–e833, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye L, Qiu L, Zhang H, Chen H, Jiang C, Hong H, Liu J. Cardiomyocytes in young infants with congenital heart disease: a three-month window of proliferation. Sci Rep 6: 23188, 2016. doi: 10.1038/srep23188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zebrowski DC, Engel FB. The cardiomyocyte cell cycle in hypertrophy, tissue homeostasis, and regeneration. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 165: 67–96, 2013. doi: 10.1007/112_2013_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]