Abstract

Systemic immune activation is the hallmark of sepsis, which can result in endothelial injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The aim of this study was to investigate heterogeneity in sepsis-mediated endothelial permeability using primary human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMECs) and the electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) platform. After plasma removal, cellular component of whole blood from 35 intensive care unit (ICU) patients with early sepsis was diluted with media and stimulated with either lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or control media. Resulting supernatants were cocultured with HPMECs seeded on ECIS plates, and resistance was continually measured. A decrease in resistance signified increased permeability. After incubation, HPMECs were detached and cell adhesion proteins were quantified using flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry, and gene expression was analyzed with quantitative PCR. Significant heterogeneity in endothelial permeability after exposure to supernatants of LPS-stimulated leukocytes was identified. ICU patients with sepsis stratified into one of the following three groups: minimal (9/35, 26%), intermediate (18/35, 51%), and maximal (8/35, 23%) permeability. Maximal permeability was associated with increased intercellular adhesion molecule-1 protein and mRNA expression and decreased vascular endothelial-cadherin mRNA expression. These findings indicate that substantial heterogeneity in pulmonary endothelial permeability is induced by supernatants of LPS-stimulated leukocytes derived from patients with early sepsis and provide insights into some of the mechanisms that induce lung vascular injury. In addition, this in vitro model of lung endothelial permeability from LPS-stimulated leukocytes may be a useful method for testing therapeutic agents that could mitigate endothelial injury in early sepsis.

Keywords: acute lung injury, endothelial injury, immune activation, sepsis, vascular leak

INTRODUCTION

Endothelial cells are one of the primary targets in sepsis (14, 16). During infection, the endothelium orchestrates an immune response that recruits activated leukocytes to the site of infection and contributes to the loss of alveolar endothelial permeability that is central to the pathogenesis of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (19, 26).

Significant heterogeneity exists in ARDS pathobiology. Although 6–7% of patients with sepsis develop ARDS (8, 20), most patients do not experience pulmonary complications. Autopsy findings of patients who meet ARDS diagnostic criteria show histological heterogeneity in lung architecture, with diffuse alveolar damage present in 12–58% of postmortem lung specimen depending on ARDS severity (29). Furthermore, ~30% of patients with ARDS fall into a hyperinflammatory phenotype associated with a poor outcome (3, 6), and profiling of ARDS pulmonary edema fluid distinguishes a distinct hypermetabolic subset in 38% of patients (24). This disease heterogeneity and the molecular mechanisms underlying the development of lung injury in patients with sepsis are inadequately understood, since we lack patient-specific data on the interplay between the immune system and endothelial dysregulation.

Our objective was to study leukocyte-mediated effects on pulmonary endothelial permeability in critically ill patients with early sepsis using primary human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMECs) and the electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) platform (9, 31). We hypothesized that, in patients with early sepsis, there would be heterogeneity in leukocyte-mediated pulmonary endothelial permeability and that endothelial injury might be associated with changes in intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 and vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection.

Patients with early sepsis were selected between November 2016 and April 2018 from prospectively enrolled patients admitted to the intensive care unit from the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital [University of California, San Francisco (USCF) Parnassus], as part of the ongoing Early Assessment of Renal and Lung Injury cohort, as previously described (1, 15). Sample collection occurred between 8:00 am and 4:00 pm to facilitate timely processing (within 1 h) and ex vivo lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. Controls included 10 healthy subjects. UCSF Institutional review approval and participant informed consent were obtained.

Whole blood stimulation.

Citrate-anticoagulated whole blood was centrifuged, and plasma was removed. The remaining cell pellet was washed with 1:10 MV media (PromoCell) and then was resuspended in 1:5 MV media. The sample was incubated at 37°C in media alone or in the presence of 5 ng/ml of LPS for 4 h, followed by centrifugation, supernatant removal, and storage at −80°C. Cryopreserved supernatants from patients with an adjudicated diagnosis of sepsis were included in ECIS assays.

ECIS.

Primary HPMECs (PromoCell, Heidelberg, Germany) were grown in MV-supplemented endothelial growth medium (PromoCell) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml), and amphotericin B (2.5 µg/ml). Applied BioPhysics 96W10idf ECIS culture arrays were pretreated with 10 mM cysteine, washed, and 100 µl of MV media with supplement, and antimicrobials were added. After equilibration for 2 h, 100 µl 7.5 × 104/well HPMECs were added. Medium was changed 24 h after seeding, and 24 h later, 150 µl of supplement and antimicrobial-free MV media were added. Confluent cells were rested for 2 h before adding four replicates of 50 µl of patient-specific unstimulated or LPS-stimulated leukocyte supernatants. To minimize ECIS assay variability, HPMECs from the same donor propagated to passage 7–8 were used. Interassay reproducibility was confirmed by testing the same patient samples on three different assay batch dates.

Endothelial permeability was quantified using the ECIS-Zθ system (Applied BioPhysics, Troy, NY). Experiments were terminated after 5 h of continuous impedance, capacitance, and resistance reading at 4,000 Hz. Resistance values were normalized to those immediately before the addition of conditions to the HPMEC monolayer. A delta normalized resistance value was calculated as follows: (mean LPS-supernatant stimulated HPMEC normalized resistance) – (mean media-supernatant stimulated HPMEC normalized resistance). Delta normalized resistance was used to compare patient-specific HPMEC injury. Endothelial permeability groups were generated using delta normalized resistance quartiles in patients with sepsis as follows: minimal change defined by the lowest quartile (more than −0.06 Ω), intermediate change defined by two middle quartiles (−0.06 to −0.2 Ω), and maximal change defined by the highest quartile (less than or equal to −0.2 Ω).

Flow cytometry.

After a 5-h incubation in 96-well ECIS plates, HPMECs were washed with HEPES BSS, incubated with Trypsin/EDTA (0.04/0.03%), and washed with Trypsin Neutralization Solution (PromoCell Detach Kit). Cells were incubated in 1:1,000 fixable viability stain 575V (BD Bioscience) for 10 min and washed, and monoclonal antibodies for surface proteins for CD31 PE (eBioscience), ICAM-1 PerCP-eFluor710 (eBioscience), and VE-cadherin (eBioscience) were added. After 20 min, cells were washed and resuspended in annexin V binding buffer, and annexin V APC (BD Bioscience) was added for 15 min. All incubations were performed at room temperature in the dark. Samples were read on a BD LSRII flow cytometer, and data were analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

RNA extraction and real-time PCR.

HPMECs were incubated for 5 h with culture supernatants, and cells were detached as described above. RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini Plus Kit (Qiagen), and 1µg of extracted RNA was reverse transcribed using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Resulting cDNA was amplified using specific primer sets (β-actin, ICAM-1, VE-cadherin) in the presence of Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Resulting copy numbers were normalized over β-actin by the comparative Ct method (25).

Microscopy.

HPMECs were seeded at 5.0 × 104/ml on glass cover slips inside 24-well plates pretreated with 25 µg/ml rat tail collagen. Cells were grown to confluency in MV media with supplement and antimicrobials. Medium was changed to 350 µl of MV media without supplement or antimicrobials for 2 h, and 150 µl cultured supernatants were added and incubated for 5 h. Cells were washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, followed by permeabilization and blocking for 1 h at room temperature (1% BSA, 5% goat serum, 0.2% Triton X-100). Primary antibodies recognizing VE-cadherin (rabbit anti-human; Abcam) and ICAM-1 (mouse anti-human; Invitrogen) were added overnight at 4°C. After three washes, Alexa Fluor 488 (goat anti-rabbit) and Alexa Fluor 594 (goat anti-mouse) secondary antibodies were added for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Cells were imaged using the Revolve R4 microscope (Echo, San Diego, CA).

Statistical methods.

Statistical analyses were done using STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp). Graphical presentation was done using Excel (Microsoft) and Prism version 5.0a (GraphPad). Normally distributed data were analyzed using parametric tests (Pearson’s correlation, 2-sample unpaired t-tests, or ANOVA). Nonnormally distributed data were analyzed using nonparametric tests (Fisher’s exact test, Spearman rank correlation, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney, or Kruskal-Wallis test). Statistical differences were considered significant if P values were <0.05.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

Thirty-five patients with early sepsis were included in analysis. These patients represented a high severity of illness group with a mean APACHE III score of 88 ± 36 (SD) and a hospital mortality of 17%. The microbial etiology and the anatomic source of sepsis were similar to previous reports (17), with lung followed by intra-abdominal source of infection being most common. Patient clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 35) | Minimal Permeability (N = 9, 26%) |

Intermediate Permeability (N = 18, 51%) |

Maximal Permeability (N = 8, 23%) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 35 | 9 (26) | 18 (51) | 8 (23) | |

| 5 h delta resistance (median, range) | −0.13 (−0.39, −0.006) | more than −0.06 | less than −0.06 to more than −0.2 | less than −0.2 | |

| Age, yr | 67 ± 18 | 68 ± 1 | 73 ± 19 | 52 ± 7 | 0.02 |

| Sex, %male (n) | 63 (22) | 60 (6) | 61 (11) | 63 (5) | 0.8 |

| WBC, median (IQR) | 12.2 (9.4, 24.3) | 10.8 (5.3, 17.6) | 11.9 (10.0, 15.5) | 24.8 (12.2, 39.2) | 0.1 |

| Vasopressors (%, n) | 37 (13) | 44 (4) | 33 (6) | 38 (3) | 0.9 |

| Positive pressure ventilation on day 1 | 49 (17) | 56 (5) | 50 (9) | 38 (3) | 0.8 |

| APACHE III | 88 ± 36 | 96 ± 40 | 87 ± 37 | 81 ± 34 | 0.7 |

| Hospital death, % (n) | 17 (6) | 33 (3) | 11 (2) | 13 (1) | 0.4 |

| Source of sepsis, % (n) | 0.2 | ||||

| Pulmonary | 57 (20) | 56 (5) | 67 (12) | 38 (3) | |

| Intra-abdominal | 26 (9) | 22 (2) | 24 (4) | 38 (3) | |

| Urinary tract | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Skin and soft tissue | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 25 (2) | |

| Other | 9 (3) | 22 (2) | 6 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Organism, % (n) | |||||

| Gram positive VE | 34 (12) | 33 (3) | 28 (5) | 50 (4) | 0.6 |

| Gram negative VE | 29 (10) | 22 (2) | 39 (7) | 13 (1) | 0.4 |

| Virus | 17 (6) | 22 (2) | 17 (3) | 13 (1) | 1 |

| Negative cultures | 37 (13) | 33 (3) | 39 (7) | 38 (3) | 1 |

Values are means ± SD; N, no. of subjects. WBC, white blood cell count; IQR, interquartile range; VE, vascular endothelial.

Pulmonary endothelial permeability response subgroups.

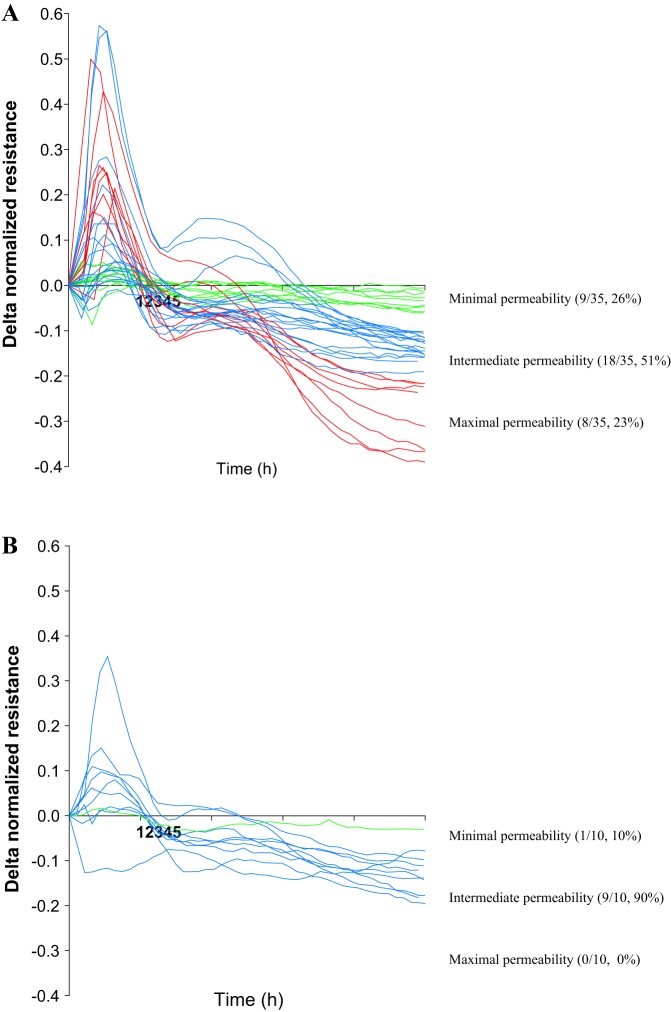

Continuous resistance measurement using the ECIS assay identified three pulmonary endothelial permeability groups at 5 h after the addition of leukocyte supernatants from patients with early sepsis. These groups were identified after the resistance change (delta) was calculated by subtracting the endothelial cell resistance after exposure to unstimulated leukocyte supernatants from the LPS-stimulated leukocyte supernatants. This divided patients into a minimal (lowest quartile of delta normalized resistance, more than −0.06 Ω, 9/35, 26%), intermediate (middle second and third quartiles of delta normalized resistance, −0.06 to −0.2 Ω, 18/35, 51%), and maximal (highest quartile of delta normalized resistance, less than −0.2 Ω, 8/35, 23%) endothelial permeability groups (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Permeability profiles after pulmonary endothelial cell exposure to supernatants obtained from a septic patient (A) and healthy control leukocytes stimulated with media or 5 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (B). Time 0 h corresponds to the addition of supernatants. Resistance change (delta) corresponded to permeability and was derived by subtracting endothelial cell resistance after exposure to unstimulated leukocyte supernatants from endothelial cell resistance after exposure to LPS-stimulated leukocyte supernatants. Five-h delta resistance was used to stratify septic patients into three permeability groups: minimal (green), intermediate (blue), and maximal (red).

When pulmonary endothelial cells were exposed to supernatants generated after LPS stimulation of leukocytes derived from 10 healthy control patients, the maximal permeability group was absent, and 9 of 10 leukocyte supernatants induced intermediate permeability and one minimal permeability (Fig. 1B).

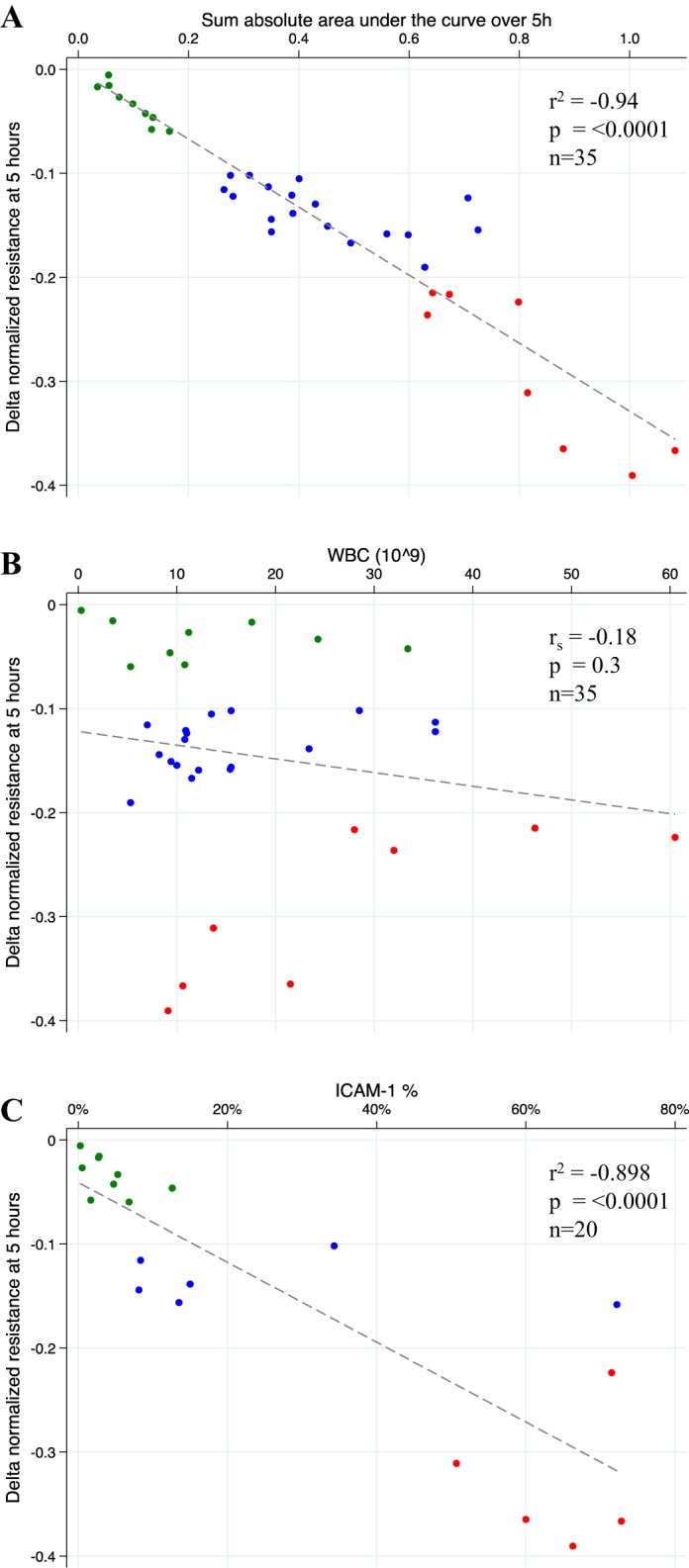

To test if cross-sectional permeability at 5 h was representative of continually measured resistance, the sum of the absolute area under the curve for the 5-h stimulation was computed. When the area under the curve was compared with the resistance at 5 h, a strong correlation was noted between increased permeability at 5 h and the sum of the absolute area under the curve (r2 = −0.94, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2A), indicating that a single resistance measurement at 5 h after endothelial cell exposure to supernatants is representative of the dynamic permeability change throughout the time of measurement.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between endothelial permeability quantified using delta normalized resistance at 5 h and the sum of the absolute area under the curve over 5 h of continuous electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) resistance measurement (A), white blood cell count (WBC) (B), and %intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 positive endothelial cells (C). ECIS permeability groups are color coded: minimal (green), intermediate (blue), maximal (red).

Endothelial permeability is not the result of an increased leukocyte count.

To test the possibility that a greater endothelial permeability may be the result of the presence of higher levels of secreted factors due to an elevated white blood cell count (WBC), we analyzed the relationship between the permeability at 5 h and the WBC (Fig. 2B). There was no significant correlation between endothelial permeability and the number of WBC (rs = −0.18, P = 0.3), indicating that the leukocyte count did not affect the magnitude of endothelial cell injury after stimulation with LPS-stimulated leukocyte supernatants derived from patients with early sepsis.

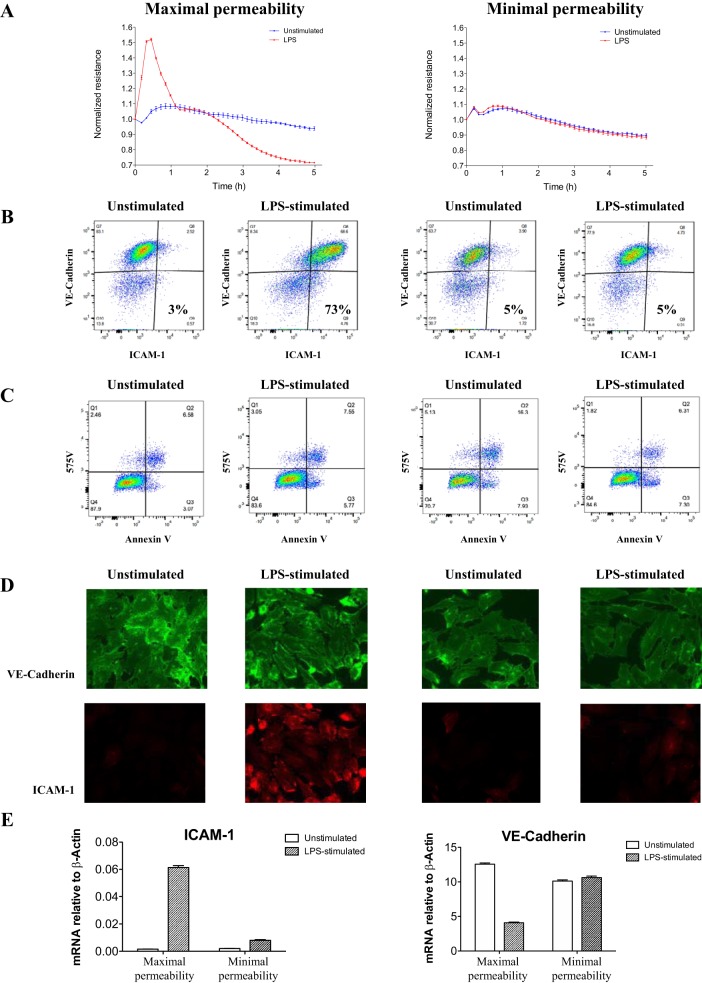

Pulmonary endothelial permeability corresponds to changes in adhesion molecule protein and gene expression.

We tested possible mechanisms for the increase in pulmonary endothelial cell permeability by measuring changes in adhesion molecule expression. ICAM-1 facilitates transcellular migration of immune cells across the endothelial surface (32), and vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin maintains vascular integrity (18, 30). Elevated plasma and edema fluid soluble ICAM-1 levels are also associated with higher mortality in acute lung injury (4) and in primary graft dysfunction (11). Therefore, we focused on these two adhesion molecules.

Representative maximal and minimal endothelial cell permeability after a 5-h exposure to supernatants from unstimulated or LPS-stimulated leukocytes was selected (Fig. 3A). Endothelial cell protein expression varied after stimulation with supernatants that had induced maximal permeability, as demonstrated by flow cytometry (Fig. 3B) and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3D). With the use of both modalities, a substantial increase in ICAM-1 protein expression was identified that distinguished maximal from minimal endothelial permeability profiles. Endothelial cell ICAM-1 expression after a 5-h stimulation with 20 individual patient samples was quantified using flow cytometry, which identified a strong correlation between endothelial permeability and ICAM-1 upregulation (r2 = 0.9, P < 0.0001, Fig. 2C). In addition, ICAM-1 gene expression significantly increased, whereas VE-cadherin gene expression decreased (Fig. 3E). These responses were noted only in endothelial cells stimulated with supernatants that induced maximal endothelial permeability in the ECIS assay.

Fig. 3.

Variation in pulmonary endothelial cell intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 and vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin protein and gene expression after a 5-h exposure to leukocyte culture supernatants derived from representative patients with early sepsis in the maximal and minimal permeability group. A: endothelial cell resistance over 5 h of continuous electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) measurement. B and C: flow cytometry scatter plots of ICAM-1 and VE-cadherin expression (B) and viability (575V) and apoptosis (annexin V) (C). D: immunohistochemistry of ICAM-1 and VE-cadherin expression. E: quantitative PCR of ICAM-1 and VE-cadherin gene expression showing an increase in ICAM-1 and decrease in VE-cadherin only in the maximal response group. Error bars represent SE of 3 technical replicates.

Last, we tested whether apoptosis or cell death was associated with pulmonary endothelial cell permeability and ICAM-1 cell surface expression. Maximal permeability after exposure to supernatants derived from unstimulated and LPS-stimulated leukocytes was not associated with altered apoptosis nor cell death, and these patterns were similar in both permeability groups (Fig. 3C). Increased ICAM-1 expression was present on viable cells (data not presented).

DISCUSSION

There is growing evidence that substantial heterogeneity is present among critically ill patients with sepsis and ARDS in both clinical and experimental studies (2, 3, 6–8, 17, 20, 24, 28, 29). Although there is also mounting data to suggest that the endothelium is a key mediator of sepsis and ARDS-associated morbidity (16, 19, 22), novel approaches to study human pulmonary endothelial cell injury are lacking. In this study, we employed the ECIS platform to study human pulmonary endothelial cell responses to soluble factors secreted by LPS-stimulated leukocytes derived from patients with early sepsis. Substantial heterogeneity in endothelial permeability was identified, suggesting that soluble factors derived from stimulated leukocytes can directly injure the endothelium and that the injury pattern can vary substantially. The increase in our in vitro measures of pulmonary endothelial permeability may in part be explained by alteration in ICAM-1 and VE-cadherin expression.

Upon endothelial cell stimulation, the NF-κB signaling cascade is initiated, which leads to altered ICAM-1 and VE-cadherin expression. A marked increase in ICAM-1 expression and downregulation of VE-cadherin have been reported in human lung tissue and in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (12, 21). In our study, when a maximal increase in pulmonary endothelial cell permeability was present, it was similarly associated with increased ICAM-1 and decreased VE-cadherin protein and mRNA expression. The upregulation of ICAM-1 facilitates the transcellular migration and recruitment of immune cells across the endothelial surface to the lung tissue (32), cytoskeletal reorganization, and vascular leak (5) while the loss of VE-cadherin may increase vascular permeability (18, 30). Therefore, a fine balance is required from both of these distinct pathways to enable an appropriate endothelial response during critical illness to either mediate an immune response targeting invading pathogens or enable inflammation-mediated acute lung injury.

Leukocyte activation in critically ill patients is associated with a significant reduction in NF-κB phosphorylation relative to healthy controls (13). Our data provide evidence that the downstream effect of leukocyte activation differentially affects pulmonary endothelial function. Although the aim of our study was not to investigate the mechanism of leukocyte dysfunction, immunosuppression may be one of the plausible explanations for the lack of endothelial responsiveness in the minimal permeability group.

The strengths of our study include a novel approach to measure pulmonary endothelial cell injury after exposure to supernatants from stimulated leukocytes derived from a relatively large number of patients with early sepsis who were clinically well phenotyped. The use of whole blood allowed a milieu representative of the in vivo immune system. The ECIS system allowed for continuous pulmonary endothelial permeability tracing, permitting the observation of a detailed response pattern over time. We analyzed both cross-sectional and continuous output data, which made it possible to identify a reliable time point to study endothelial phenotypic changes using flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, and qPCR.

There are limitations to this study. First, the cohort size, although sufficient to identify heterogeneity in pulmonary endothelial cell responses, is too small to facilitate correlation with clinical outcomes. Second, we tested only two mechanisms of endothelial cell injury, focusing on cell surface protein expression. However, other mechanisms may explain endothelial injury, including altered expression of other adhesion and junctional proteins, cytoskeletal rearrangement (10), leukocyte distribution (23), or the presence of cell-free hemoglobin (27). Third, the use of whole blood stimulation prevented the determination of leukocyte subpopulations (neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte) or red blood cells responsible for inducing pulmonary endothelial injury. Furthermore, we did not explore what factors present in supernatants derived from activated leukocytes contributed to endothelial permeability, since this was beyond the scope of these studies. Therefore, the delineation of mediators secreted by leukocytes responsible for the increase in pulmonary endothelial permeability deserves further study.

In conclusion, the ECIS platform can be reliably used to study human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell injury. Heterogeneity in endothelial cell permeability identified by the ECIS platform may help to explain the relationship between an increase in lung vascular permeability induced by systemic inflammation and acute lung injury. This platform may be a useful tool for testing therapeutic agents that mitigate endothelial injury in critical illness.

GRANTS

Dr. Leligdowicz was supported by the University of Toronto Clinician Investigator Program and the Clinician Scientist Training Program and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-51856 (M. A. Matthay), HL-140026 (C. S. Calfee), and HL-140026 (K. D. Liu).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.L., K.D.L., C.S.C., and M.A.M. conceived and designed research; A.L., L.F.C., A.J., and K.V. performed experiments; A.L., L.F.C., and M.A.M. analyzed data; A.L., L.F.C., K.D.L., C.S.C., and M.A.M. interpreted results of experiments; A.L. prepared figures; A.L. drafted manuscript; A.L., K.D.L., C.S.C., and M.A.M. edited and revised manuscript; A.L., L.F.C., A.J., K.V., K.D.L., C.S.C., and M.A.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank patients and families for participation in the Early Assessment of Renal and Lung Injury cohort and Alpa Mahuvakar and Byron Miyazawa for assistance in fluorescent microscopy experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrawal A, Matthay MA, Kangelaris KN, Stein J, Chu JC, Imp BM, Cortez A, Abbott J, Liu KD, Calfee CS. Plasma angiopoietin-2 predicts the onset of acute lung injury in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 736–742, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1460OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnham KL, Davenport EE, Radhakrishnan J, Humburg P, Gordon AC, Hutton P, Svoren-Jabalera E, Garrard C, Hill AV, Hinds CJ, Knight JC. Shared and Distinct Aspects of the Sepsis Transcriptomic Response to Fecal Peritonitis and Pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196: 328–339, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201608-1685OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calfee CS, Delucchi K, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Ware LB, Matthay MA, Network NA; NHLBI ARDS Network . Subphenotypes in acute respiratory distress syndrome: latent class analysis of data from two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med 2: 611–620, 2014. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calfee CS, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Conner ER Jr, Matthay MA, Ware LB, Network NARDSCT; NHLBI Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Clinical Trials Network . Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and clinical outcomes in patients with acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 35: 248–257, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1235-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark PR, Manes TD, Pober JS, Kluger MS. Increased ICAM-1 expression causes endothelial cell leakiness, cytoskeletal reorganization and junctional alterations. J Invest Dermatol 127: 762–774, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Famous KR, Delucchi K, Ware LB, Kangelaris KN, Liu KD, Thompson BT, Calfee CS, Network A; ARDS Network . Acute respiratory distress syndrome subphenotypes respond differently to randomized fluid management strategy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195: 331–338, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox ED, Heffernan DS, Cioffi WG, Reichner JS. Neutrophils from critically ill septic patients mediate profound loss of endothelial barrier integrity. Crit Care 17: R226, 2013. doi: 10.1186/cc13049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK, Adesanya A, Chang SY, Hou P, Anderson H 3rd, Hoth JJ, Mikkelsen ME, Gentile NT, Gong MN, Talmor D, Bajwa E, Watkins TR, Festic E, Yilmaz M, Iscimen R, Kaufman DA, Esper AM, Sadikot R, Douglas I, Sevransky J, Malinchoc M, Illness USC; U.S. Critical Illness and Injury Trials Group: Lung Injury Prevention Study Investigators (USCIITG-LIPS) . Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury: evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 462–470, 2011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0549OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giaever I, Keese CR. Monitoring fibroblast behavior in tissue culture with an applied electric field. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81: 3761–3764, 1984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.12.3761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg NM, Steinberg BE, Slutsky AS, Lee WL. Broken barriers: a new take on sepsis pathogenesis. Sci Transl Med 3: 88ps25, 2011. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton BC, Kukreja J, Ware LB, Matthay MA. Protein biomarkers associated with primary graft dysfunction following lung transplantation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 312: L531–L541, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00454.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herwig MC, Tsokos M, Hermanns MI, Kirkpatrick CJ, Müller AM. Vascular endothelial cadherin expression in lung specimens of patients with sepsis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome and endothelial cell cultures. Pathobiology 80: 245–251, 2013. doi: 10.1159/000347062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoogendijk AJ, Garcia-Laorden MI, van Vught LA, Wiewel MA, Belkasim-Bohoudi H, Duitman J, Horn J, Schultz MJ, Scicluna BP, van ’t Veer C, de Vos AF, van der Poll T. Sepsis patients display a reduced capacity to activate nuclear factor-κB in multiple cell types. Crit Care Med 45: e524–e531, 2017. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ince C, Mayeux PR, Nguyen T, Gomez H, Kellum JA, Ospina-Tascón GA, Hernandez G, Murray P, De Backer D, Workgroup AX; ADQI XIV Workgroup . The Endothelium in Sepsis. Shock 45: 259–270, 2016. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kangelaris KN, Prakash A, Liu KD, Aouizerat B, Woodruff PG, Erle DJ, Rogers A, Seeley EJ, Chu J, Liu T, Osterberg-Deiss T, Zhuo H, Matthay MA, Calfee CS. Increased expression of neutrophil-related genes in patients with early sepsis-induced ARDS. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308: L1102–L1113, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00380.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee WL, Slutsky AS. Sepsis and endothelial permeability. N Engl J Med 363: 689–691, 2010. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1007320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leligdowicz A, Dodek PM, Norena M, Wong H, Kumar A, Kumar A; Co-operative Antimicrobial Therapy of Septic Shock Database Research Group . Association between source of infection and hospital mortality in patients who have septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189: 1204–1213, 2014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1875OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maniatis NA, Orfanos SE. The endothelium in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care 14: 22–30, 2008. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f269b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest 122: 2731–2740, 2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikkelsen ME, Shah CV, Meyer NJ, Gaieski DF, Lyon S, Miltiades AN, Goyal M, Fuchs BD, Bellamy SL, Christie JD. The epidemiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients presenting to the emergency department with severe sepsis. Shock 40: 375–381, 2013. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182a64682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller AM, Hermanns MI, Cronen C, Kirkpatrick CJ. Comparative study of adhesion molecule expression in cultured human macro- and microvascular endothelial cells. Exp Mol Pathol 73: 171–180, 2002. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2002.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opal SM, van der Poll T. Endothelial barrier dysfunction in septic shock. J Intern Med 277: 277–293, 2015. doi: 10.1111/joim.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ploppa A, Schmidt V, Hientz A, Reutershan J, Haeberle HA, Nohé B. Mechanisms of leukocyte distribution during sepsis: an experimental study on the interdependence of cell activation, shear stress and endothelial injury. Crit Care 14: R201, 2010. doi: 10.1186/cc9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers AJ, Contrepois K, Wu M, Zheng M, Peltz G, Ware LB, Matthay MA. Profiling of ARDS pulmonary edema fluid identifies a metabolically distinct subset. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 312: L703–L709, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00438.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3: 1101–1108, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seeley EJ, Matthay MA, Wolters PJ. Inflection points in sepsis biology: from local defense to systemic organ injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L355–L363, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00069.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaver CM, Upchurch CP, Janz DR, Grove BS, Putz ND, Wickersham NE, Dikalov SI, Ware LB, Bastarache JA. Cell-free hemoglobin: a novel mediator of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 310: L532–L541, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00155.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sweeney TE, Azad TD, Donato M, Haynes WA, Perumal TM, Henao R, Bermejo-Martin JF, Almansa R, Tamayo E, Howrylak JA, Choi A, Parnell GP, Tang B, Nichols M, Woods CW, Ginsburg GS, Kingsmore SF, Omberg L, Mangravite LM, Wong HR, Tsalik EL, Langley RJ, Khatri P. Unsupervised analysis of transcriptomics in bacterial sepsis across multiple datasets reveals three robust clusters. Crit Care Med 46: 915–925, 2018. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thille AW, Esteban A, Fernández-Segoviano P, Rodriguez JM, Aramburu JA, Peñuelas O, Cortés-Puch I, Cardinal-Fernández P, Lorente JA, Frutos-Vivar F. Comparison of the Berlin definition for acute respiratory distress syndrome with autopsy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 761–767, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-1981OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vestweber D, Winderlich M, Cagna G, Nottebaum AF. Cell adhesion dynamics at endothelial junctions: VE-cadherin as a major player. Trends Cell Biol 19: 8–15, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wegener J, Keese CR, Giaever I. Electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) as a noninvasive means to monitor the kinetics of cell spreading to artificial surfaces. Exp Cell Res 259: 158–166, 2000. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, Froio RM, Sciuto TE, Dvorak AM, Alon R, Luscinskas FW. ICAM-1 regulates neutrophil adhesion and transcellular migration of TNF-alpha-activated vascular endothelium under flow. Blood 106: 584–592, 2005. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]