Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a common consequence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and remains a primary contributor to increased morbidity and mortality among preterm infants. Unfortunately, at the present time, there are no reliable early predictive markers for BPD-associated PH. Considering its health consequences, understanding in utero perturbations that lead to the development of BPD and BPD-associated PH and identifying early predictive markers is of utmost importance. As part of the discovery phase, we applied a multiplatform metabolomics approach consisting of untargeted and targeted methodologies to screen for metabolic perturbations in umbilical cord blood (UCB) plasma from preterm infants that did (n = 21; cases) or did not (n = 21; controls) develop subsequent PH. A total of 1,656 features were detected, of which 407 were annotated by metabolite structures. PH-associated metabolic perturbations were characterized by reductions in major choline-containing phospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholines and sphingomyelins, indicating altered lipid metabolism. The reduction in UCB abundances of major choline-containing phospholipids was confirmed in an independent validation cohort consisting of UCB plasmas from 10 cases and 10 controls matched for gestational age and BPD status. Subanalyses in the discovery cohort indicated that elevations in the oxylipins PGE1, PGE2, PGF2a, 9- and 13-HOTE, 9- and 13-HODE, and 9- and 13-KODE were positively associated with BPD presence and severity. This expansive evaluation of cord blood plasma identifies compounds reflecting dyslipidemia and suggests altered metabolite provision associated with metabolic immaturity that differentiate subjects, both by BPD severity and PH development.

Keywords: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, lipids, metabolomics, oxylipins, pulmonary hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a chronic lung disease triggered by barotrauma, volutrauma, and oxygen toxicity, resulting in arrest of alveolar development and varying degrees of interstitial fibrosis (17, 51). It is the most common complication of preterm birth, particularly in extremely preterm infants born before 28 wk of gestation, and affects over 10,000 infants per year in the United States (38). Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a common complication of BPD and is characterized by remodeling of the pulmonary vasculature, increased vascular tone, abnormal pulmonary vasoreactivity, and right ventricular hypertrophy. The development of PH dramatically increases morbidity and mortality among preterm infants (51). The mechanisms mediating pulmonary resistance and altered reactivity are incompletely characterized. While BPD and PH share many risk factors, they have distinct pathophysiologies. It has been postulated that PH is triggered, in part, by fetal exposure to a harmful intrauterine environment (5, 15). This hypothesis is supported by associations between BPD-associated PH and both fetal growth restriction and oligohydramnios (43). Early screening echocardiograms are variable predictors of BPD-associated PH (9), and diagnostic biomarkers of this condition do not yet exist. Umbilical cord blood (UCB) screening presents an opportunity to understand in utero perturbations that lead to the development of PH in preterm infants in the presence of BPD.

Metabolomics is the study of small molecules and biochemical intermediates (metabolites), which are perturbed by or regulators of other regulatory mechanisms (e.g., genome, transcriptome, and proteome) and environmental stimuli. A metabolomics characterization can, therefore, present a detailed organismal phenotype. Successful application of metabolomics to provide novel insights into pathologies and develop prognostic and diagnostic markers of disease are growing and compelling (18, 52, 63). Since the pathophysiology of BPD and BPD-associated PH potentially has strong metabolic components (40), the application of metabolomics represents a promising approach for the identification of diagnostic biomarkers and insights into the metabolic alterations underlying these common diseases of very premature infants.

In the current study, we used a multiplatform metabolomics approach to evaluate alterations in the UCB plasma metabolome of preterm infants who did (n = 21; cases) or did not (n = 21; controls) develop subsequent PH. Metabolites of interest that were reflective of PH development were validated in an independent cohort consisting of UCB plasmas from 10 cases and 10 controls matched for gestational age and BPD status. To our knowledge, this study is the first comprehensive evaluation of metabolic alterations in the context of PH. We hypothesize that fetal circulating biomarkers identified in UCB represent in utero insults that trigger metabolic pathways associated with BPD severity and PH development.

METHODS

Patient sample collection.

Cord blood plasma samples were obtained from an established cohort of premature infants born at Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, IL. This prospective cohort study enrolls all infants born <37 wk (2008 to present), with collection of cord blood at delivery and follow-up of premature infant outcomes, including BPD and PH (62). In the discovery cohort, 21 infants born at <32 wk with PH, determined by routine echocardiogram evaluation at 36 wk corrected-age using a previously published algorithm (15), were included in the study as PH cases. Twenty-one non-PH patient samples matched one to one by gestational age (±1 wk) were included as controls (Table 1). Severity (mild, moderate, severe) of BPD was defined according to the National Institutes of Health consensus workshop definition of BPD (28). In infants with gestational ages <32 wk, moderate BPD is defined by the need for <30% oxygen at 36 wk postmenstrual age or discharge (whichever comes first), whereas severe BPD is defined by the need for >30% oxygen and/or positive pressure at the same time point. In a subsequent sample of preterm infants enrolled at Prentice after the above discovery cohort, we identified a validation cohort (n = 20) in which criteria for cases was restricted to infants with moderate-severe BPD with PH (n = 10) and matched 1:1 with 10 patients of similar BPD severity (moderate-severe only) who did not have associated PH (Table 2). Cord blood plasma samples from these 20 patients were used for validation of the discovery cohort findings. All cord blood was collected at delivery into EDTA tubes and spun at 3,000 revolutions/min for 10 min in a refrigerated table-top centrifuge. Plasma was separated into aliquots and archived at −80°C. Samples were shipped to the West Coast Metabolomics Center at University of California, Davis. The above study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University. Maternal informed consent was obtained before participation of all mothers and their infants.

Table 1.

Discovery cohort patient characteristics

| PH− | PH+ | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 21 | 21 | |

| Subject characteristics | |||

| Birth weight, g | 1,079 ± 384 | 969 ± 486 | 0.418 |

| Gestation age, wk | 27 ± 3 | 27 ± 3 | 0.948 |

| Sex/male, n (%) | 11 (52) | 11 (52) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African American, n (%) | 6 (28.6) | 7 (33.3) | |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 9 (42.9) | 8 (38.0) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 6 (28.6) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (10) | |

| BPD characteristics | |||

| Yes/no | 14/7 | 20/1 | |

| Mild/moderate/severe | 7/4/3 | 2/7/11 |

Values for weight and age are means ± SD; n = number of participants. PH, pulmonary hypertension; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Significance was determined by two-sided t-test.

Table 2.

Validation cohort patient characteristics

| PH− | PH+ | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 21 | 21 | |

| Subject characteristics | |||

| Birth weight, g | 1,091 ± 201 | 878 ± 162 | 0.02 |

| Gestation age, wk | 27 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 | 0.13 |

| Sex/male, n (%) | 6 (60) | 7 (70) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African American, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (50.0) | |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 3 (30.0) | 3 (30.0) | |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 5 (50.0) | 2 (20) | |

| BPD characteristics | |||

| Yes/no | 10/0 | 10/0 | |

| Mild/moderate/severe | 0/10 | 0/10 |

Values for weight and age are means ± SD; n = number of participants. PH, pulmonary hypertension; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Significance was determined by two-sided t-test.

Metabolomic, lipidomic, and oxylipin analyses.

The miniX database (48) was used as a laboratory information management system and for sample randomization before all analytical procedures. Samples were analyzed in a single batch on each platform.

For analysis of complex lipids, UCB plasma aliquots (20 µl) were extracted with methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) in the presence of analytical surrogates, as previously described (18), and separated with an Agilent 1290A Infinity ultra-high performance liquid chromatograph and detected with an Agilent 6530 accurate-Mass QTOF in both positive and negative mode (18, 12a).

Discovery cohort data were processed using MZmine v. 2.10; validation cohort data were processed in MS-DIAL (59). Lipids were identified by precursor accurate mass and manual MS/MS comparison to LipidBlast mass spectra (30) in addition to confirmation by authentic lipid standards. Data, reported as peak heights for the quantification ion (m/z) at the specific retention time for each annotated and unknown metabolite, were normalized to the class-specific internal standard (annotated) or to the internal standard that had the closest retention time (unknowns). A human plasma laboratory reference material (Bioreclamation plasma, BioIVT, Hicksville, NY) and method blanks were used to assess data quality.

For analysis of primary metabolites, half of the polar (bottom) layer from the MTBE lipid extract was dried under reduced pressure, derivatized by trimethylsilylation/methoximation, and metabolite levels were determined using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph coupled to a Leco Pegasus IV time-of-flight mass spectrometer, as previously described (18). Acquired spectra were further processed using the BinBase database (20, 48), including metabolite annotations by retention index and mass spectra matching (18). Data, reported as quantitative ion peak heights, were normalized by the sum intensity of all annotated metabolites across the entire study and used for further statistical analysis.

For analysis of biogenic amines, including arginine, citrulline, and ornithine, the remaining half of the polar (bottom) layer from the MTBE extract was dried under reduced pressure and resuspended in 60 µl of 80:20 acetonitrile/water containing the internal standards 1-cyclohexyl-ureido-3-dodecanoic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 2 µg/ml l-arginine-15N2 (Cambridge Isotope), and Val-Tyr-Val (Sigma-Aldrich). Metabolites were separated by injecting 3-μl sample in hydrophilic interaction chromatography mode using an Agilent 1290A Infinity ultrahigh performance liquid chromatograph pump with a Waters BEH Amide column (2.1 mm × 15 cm, 1.7-μm particles) with solvent A (10 mM ammonium formate + 0.125% formic acid, pH 3) and solvent B (95:5 vol/vol acetonitrile-water with 10 mM ammonium formiate + 0.125% formic acid, pH 3) and the following gradient: 0–2 min 100% (B), 2–7 min 70% (B), 7.7–9 min 40% (B), 9.5–10.25 min 30% (B), 10.25–12.75 min 100% (B), and 16.75 min 100% (B), with a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. Column temperature was 40°C. Data were acquired on an Agilent 6550 QTOF mass spectrometer at 10,000 resolving power in 4.5 kV positive electrospray ionization mode at 2 Hz with scan range 60–1,200 Da, 3-Da precursor isolation window, and 45-eV collision energy. Agilent MassHunter software was used to quantify peaks according to their external standard curve (ornithine and citrulline) or the internal standard l-arginine-15N2 (arginine) and presented as µM concentrations. Pooled Bioreclamation plasma (BioIVT, Hicksville, NY) was included to assess and monitor data quality. Data were processed as given above.

For analysis of oxylipins, analytes were isolated using the Ostro Pass Through Sample Preparation Plate (Waters, Milford, MA). After the addition of plasma (50 μl) to plate wells, plasma was spiked with antioxidants (5 µl of 0.2 mg/ml butylated hydroxytoluene-EDTA in 1:1 MeOH-water) and deuterated analytical surrogates (5 μl of 1,000 nM in MeOH). Acetonitrile (150 μl) with 1% formic acid was forcefully added to the sample and aspirated 3 times to mix. Samples were eluted into glass inserts containing 10 μl 20% glycerol by applying a vacuum at 15 Hg for 10 min. Eluent was dried by speed vacuum. Samples were reconstituted with the internal standards 1-cyclohexyl-ureido-3-dodecanoic acid and 1-phenyl ureido, 3-hexanoic acid at 100 nM (50:50 MeOH-acetonitrile) and filtered at 0.1 µm by centrifugation. Analytes in a 50-μl extract aliquot were separated with a Waters Acquity UPLC (Waters) using modifications of a previously published protocol (24, 53). Separated residues were detected by negative mode electrospray ionization using multiple reaction monitoring on an API 4000 QTrap (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA). Five- to ten-point calibration curves (r2 ≥ 0.997) together with internal standard methods were used to quantify analytes. The acquired data were processed with Sciex MultiQuant version 3.0. Standards were either synthesized or purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI).

Data analysis.

Statistical analyses were carried out after sex difference and gestation period covariate adjustment of metabolite values. Specifically, a linear model was generated to describe differences in metabolite values because of sex difference and gestational period; the residuals were kept and used for further statistical analyses. Covariate-adjusted data were log10-transformed, and significance was determined using a two-sided t-test or Welch t-test. The significance levels (i.e., P values) were adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing according to Benjamini and Hochberg (4) at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 5% (abbreviated pFDR <0.05). FDR correction was carried out independently on metabolites with known annotations only and on the entire data set. To evaluate the contributions of BPD on detected metabolite levels, a subanalysis was conducted on UCB from subjects that exhibited varying degrees of BPD but did not develop PH (Table 1). Kendall rank correlations were used to assess significant associations (P < 0.05) between UCB metabolite abundances and the presence and severity of BPD. Additionally, to minimize confounding effects because of differences in BPD presence and severity between the PH and non-PH cohort, we performed a secondary subanalysis on only those subjects with moderate to severe BPD who did (n = 18) or did not (n = 7) develop subsequent PH. For subanalyses, significance testing was carried out using a Welch t-test and adjusted for false discovery as described above. For the validation cohort, to test our a prior hypothesis of decreased choline-containing phospholipids in the PH group based on the results of the discovery cohort, significance was determined by one-sided Mann-Whitney U-test.

Network mapping was performed in Cytoscape (49) to encode statistical results through network edge and node attributes. Network edge construction was performed with MetaMapR (25).

All data and detailed information on sample preparation and data acquisition has been archived as project PR000207 can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.21228/M8N30T on the National Institutes of Health Metabolomics Workbench data repository (54).

RESULTS

Comparison of physical and biochemical characteristics.

In the discovery cohort, the mean gestational age was 27 wk for both non-PH and PH cohorts, which showed equivalent representation of boys and girls, gestational age, and birth weight (Table 1). The ethnicity for all study participants was 31.0% African American, 40.5% Caucasian, 23.8% Hispanic, and 4.8% Asian. (Table 1). The prevalence of BPD was higher in preterm infants who developed PH (20/21; 95%) relative to those who did not (14/21; 67%) (Table 1). Preterm infants with moderate to severe BPD were more likely to develop PH (relative risk: 2.9; confidence interval: 1.5–5.7; Fisher exact test P value: 0.001) (Table 1). Validation cohort characteristics included gestational ages of 27.6 and 26.8 wk for the non-PH and PH groups, respectively. Birth weight was significantly lower in the PH group (P < 0.02) (Table 2).

A two-sided t-test or Welch t-test, depending on individual analyte variance, was used to identify 87 significantly altered sex difference- and gestational period-adjusted metabolic features (raw P value < 0.05) between PH and control. No metabolite remained significant after FDR adjustment whether evaluating knowns only or the entire data set. Of the 87 metabolites with a raw P value < 0.05, 43 (49.4%) had known annotations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Significantly differential circulating metabolites and lipids in PH versus non-PH

| Compound | Domain | PH− | PH+ | Fold Change† | P Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary metabolites | |||||

| Glucose-6-phosphate | Carbohydrate | 57.3 ± 40 | 149 ± 130 | 2.6 | 0.007 |

| Threitol | Carbohydrate | 174 ± 99 | 289 ± 220 | 1.7 | 0.045 |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate | Organic acid | 72.9 ± 64 | 184 ± 150 | 2.5 | 0.007 |

| Asparagine | Amino acid or amide | 413 ± 280 | 598 ± 240 | 1.4 | 0.041 |

| Creatinine | Amino acid or amide | 669 ± 550 | 1,010 ± 580 | 1.5 | 0.033 |

| Choline | Other primary | 5,150 ± 3,600 | 11,300 ± 8,200 | 2.2 | 0.036 |

| Bisphosphoglycerol.NIST | Lipid | 148 ± 84 | 255 ± 180 | 1.7 | 0.047 |

| Complex lipids | |||||

| Eicosenoic acid | Free fatty acid | 334 ± 500 | 464 ± 280 | 1.4 | 0.024 |

| α-Linolenic acid | Free fatty acid | 506 ± 680 | 936 ± 700 | 1.9 | 0.006 |

| Oleic acid | Free fatty acid | 26,500 ± 47,000 | 36,200 ± 22,000 | 1.4 | 0.041 |

| Palmitoleic acid | Free fatty acid | 1,200 ± 1,700 | 2,320 ± 1,700 | 1.9 | 0.007 |

| Acylcarnitine (C14:1) | Acylcarnitine | 2,000 ± 1,500 | 3,900 ± 3,300 | 2 | 0.042 |

| PC (p40:3) or (o40:4) | Phospholipid | 2,400 ± 2,300 | 970 ± 750 | 0.4 | 0.021 |

| PC (p36:2) or (o36:3) | Phospholipid | 5,790 ± 3,700 | 3,330 ± 2,600 | 0.6 | 0.043 |

| TG (60:11) | Triacylglyceride | 6,840 ± 6,400 | 14,800 ± 11,000 | 2.2 | 0.016 |

| TG (58:9) | Triacylglyceride | 28,100 ± 19,000 | 54,300 ± 32,000 | 1.9 | 0.035 |

| TG (58:8) | Triacylglyceride | 64,400 ± 46,000 | 118,000 ± 71,000 | 1.8 | 0.035 |

| TG (58:10) | Triacylglyceride | 5,690 ± 4,300 | 11,800 ± 8,700 | 2.1 | 0.02 |

| TG (56:9) | Triacylglyceride | 4,830 ± 4,100 | 9,720 ± 5,700 | 2 | 0.016 |

| TG (54:8) | Triacylglyceride | 2,170 ± 1,800 | 3,670 ± 2,800 | 1.7 | 0.043 |

| TG (53:4) | Triacylglyceride | 4,270 ± 2,700 | 8,410 ± 6,100 | 2 | 0.039 |

| Oxylipins | |||||

| 9,10-DiHOME | Diol | 1.33 ± 0.89 | 2.55 ± 1.5 | 1.9 | 0.003 |

| 9,10-DiHODE | Diol | 0.124 ± 0.079 | 0.187 ± 0.097 | 1.5 | 0.023 |

| 19,20-DiHDoPE | Diol | 2.17 ± 1.4 | 3.31 ± 1.9 | 1.5 | 0.047 |

| 15,16-DiHODE | Diol | 2.54 ± 3.8 | 4.91 ± 5.8 | 1.9 | 0.006 |

| 14,15-DiHETE | Diol | 0.795 ± 0.64 | 1.49 ± 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.018 |

| 12,13-DiHOME (area ratio%)¥ | Diol | 1.17 ± 8.2 | 2.52 ± 1.8 | 2.2 | 0.003 |

| 9,10-EpOME | Epoxide | 0.953 ± 0.82 | 1.71 ± 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.012 |

| 15,16-EpODE | Epoxide | 2.02 ± 2.5 | 3.66 ± 3.9 | 1.8 | 0.039 |

| 12,13-EpOME | Epoxide | 2.19 ± 1.4 | 3.71 ± 2.9 | 1.7 | 0.019 |

| 12,13-Ep-9-KODE | Epoxide | 5.64 ± 2.7 | 8.92 ± 8.6 | 1.6 | 0.048 |

| 9-HOTE | Hydroxy acid | 1.03 ± 0.6 | 2.18 ± 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.002 |

| 9-HODE | Hydroxy acid | 19.3 ± 11 | 34.9 ± 31 | 1.8 | 0.008 |

| 9-HETE | Hydroxy acid | 15.6 ± 10 | 37.1 ± 37 | 2.4 | 0.024 |

| 5-HETE | Hydroxy acid | 7.98 ± 6.1 | 16.9 ± 15 | 2.1 | 0.02 |

| 5-HEPE | Hydroxy acid | 0.477 ± 0.25 | 0.754 ± 0.46 | 1.6 | 0.022 |

| 17-HDoHE | Hydroxy acid | 7.83 ± 7.7 | 13.9 ± 13 | 1.8 | 0.049 |

| 13-HOTE | Hydroxy acid | 2.17 ± 1.5 | 4.8 ± 4.5 | 2.2 | 0.004 |

| 13-HODE | Hydroxy acid | 22.4 ± 12 | 42.6 ± 40 | 1.9 | 0.008 |

| 9-KODE | Ketone | 20.3 ± 9.6 | 32.1 ± 30 | 1.6 | 0.047 |

| 13-KODE | Ketone | 8.41 ± 4.1 | 13.8 ± 13 | 1.6 | 0.034 |

| PGE1 | Prostanoid | 0.29 ± 0.19 | 0.478 ± 0.35 | 1.6 | 0.034 |

Values are means ± SD. Primary metabolites and complex lipids are reported as relative peak heights. Oxylipins are reported as concentrations (nM), with the exception of 12,13-DiHOME, which is expressed as area ratio percent. HODE, 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PH, pulmonary hypertension; TG, triacylglyceride.

Fold change of PH+/PH− and

significance was determined by two-sided t-test or Welch t-test, depending on individual analyte variance.

Modest perturbations of primary metabolites precede BPD-associated PH.

Analysis of primary metabolites in UCB identified 7 differential (increased/decreased) metabolites between the UCB from subjects who did or did not develop subsequent PH. These included 2.6- and 2.5-fold elevations in the glycolytic intermediate glucose-6-phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate (Table 3). Similarly, the amino acids asparagine and creatinine were found to be elevated 1.4- and 1.5-fold in neonates who subsequently developed PH, respectively (Table 3). Interestingly, choline was 2.2-fold higher in UCB plasma from the PH group.

Dyslipidemia precedes PH.

UCB plasma from preterm infants who developed subsequent PH showed elevations in circulating free fatty acids (FFAs) eicosanoic acid, α-linolenic acid (ALA), oleic acid, and palmitoleic acid (Table 3). Total FFAs were elevated 1.41-fold in PH relative to non-PH (Table 3). The PH-associated elevation in FFAs was met with a similar twofold elevation in circulating acylcarnitine (C14:1) and increases in numerous triacylglycerides (TG), which was led by a 2.2-fold increase in TG (60:11) (Table 3). Despite the elevation in select acylcarnitines and TGs, no significant differences were observed when looking at global content of the respective lipid classes (Table 4). This may suggest a shift in fatty acid composition, as suggested by the changes in specific fatty acids. Inverse to the elevations in aforementioned lipid species, we observed a 60 and 40% reduction in the select circulating plasmalogen phosphatidylcholine (PC) (plasmanyl-p40:3 or plasmenyl-o40:4) and PC (plasmanyl-p40:3 or plasmenyl-o40:4), respectively (Table 2). Ether linkages of plasmalogens are classified as “p” for alkyl and “o” for alkenyl. Similarly, global abundances of PCs and sphingomyelins (SMs) were reduced 25 and 37% in the PH group relative to control, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

PH-associated perturbations in classes of major structural lipids and oxylipins

| Lipid Domain* | PH− | PH+ | Fold Change§ | P Value¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acylcarnitines (14)† | 1,360,000 ± 610,000 | 1,720,000 ± 670,000 | 1.26 | 0.0915 |

| Ceramides (6) | 12,000 ± 6,900 | 9,090 ± 4,400 | 0.76 | 0.1369 |

| Cholesterol esters (7) | 215,000 ± 110,000 | 172,000 ± 76,000 | 0.8 | 0.3503 |

| Free fatty acids (19) | 79,600 ± 81,000 | 105,000 ± 45,000 | 1.32 | 0.0123 |

| Glucosyl ceramides (2) | 17,900 ± 14,000 | 7,200 ± 5,100 | 0.4 | 0.0599 |

| Lysophosphatidyl cholines (12) | 410,000 ± 2e + 05 | 347,000 ± 150,000 | 0.85 | 0.3189 |

| Lysophosphatidyl ethanolamines (4) | 9,470 ± 4,900 | 7,100 ± 3,600 | 0.75 | 0.2222 |

| Phosphatidyl cholines (34) | 11,200,000 ± 3,500,000 | 8,390,000 ± 3,500,000 | 0.75 | 0.017 |

| Phosphatidyl ethanolamines (3) | 17,200 ± 7,800 | 15,800 ± 11,000 | 0.92 | 0.3332 |

| Plasmalogen-PCs (24) | 384,000 ± 280,000 | 240,000 ± 150,000 | 0.63 | 0.0626 |

| Plasmalogen-PEs (3) | 9,270 ± 5,700 | 9,730 ± 8,700 | 1.05 | 0.753 |

| Sphingomyelins (26) | 2,050,000 ± 980,000 | 1,310,000 ± 640,000 | 0.64 | 0.0151 |

| Triglycerides (48) | 4,810,000 ± 2,200,000 | 5,790,000 ± 3,200,000 | 1.2 | 0.3394 |

| C18_Diols (5) | 5.21 ± 4.8 | 9.33 ± 7.4 | 1.8 | 0.0069 |

| C20_Diols (6) | 15.1 ± 8.6 | 20.3 ± 12 | 1.34 | 0.1299 |

| C22_Diols (1) | 2.17 ± 1.4 | 3.31 ± 1.9 | 1.5 | 0.047 |

| C18_Epoxides (5) | 18.3 ± 8 | 26.4 ± 13 | 1.4 | 0.0092 |

| C20_Epoxides (2) | 3.69 ± 1.8 | 7.44 ± 13 | 2.02 | 0.1704 |

| C18_Hydroxy acids (4) | 44.9 ± 25 | 84.5 ± 75 | 1.9 | 0.0075 |

| C20_Hydroxy acids (10) | 263 ± 160 | 576 ± 1100 | 2.2 | 0.1611 |

| C22_Hydroxy acids (2) | 80.2 ± 52 | 183 ± 400 | 2.3 | 0.224 |

| C18_Ketones (2) | 28.7 ± 14 | 45.8 ± 43 | 1.6 | 0.0441 |

| C20_Prostacyclins or leukotrienes (7) | 67.2 ± 67 | 94.2 ± 100 | 1.4 | 0.3806 |

Values (means ± SD) represent the summed intensities of individual annotated lipids belonging to the respective lipid class. Complex lipids are presented as summed peak intensities; oxylipins are shown as summed concentrations (nM). PH, pulmonary hypertension.

Major lipid classes,

number of measured molecules,

fold change of PH+/PH−, and

significance was determined by two-sided t-test or Welch t-test, depending on individual analyte variance.

Oxylipins are elevated before the onset of BPD-associated PH.

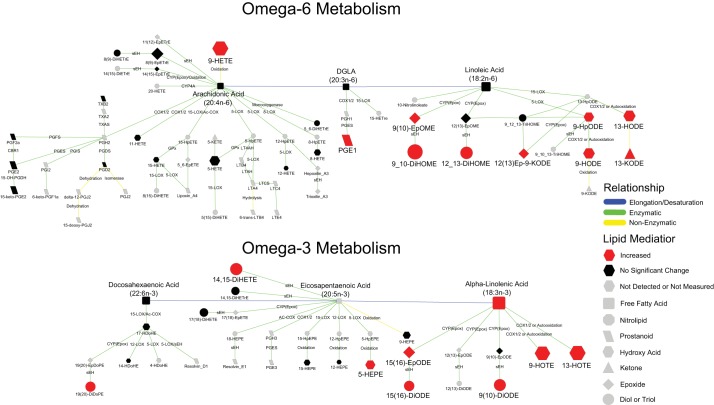

Of the 43 altered annotated metabolites, 21 (49%) were oxygenated lipids and were uniformly elevated in PH cord blood plasma (Table 3). The largest difference was a 2.4-fold increase in 9-HETE, a nonenzymatic oxidation product of arachidonic acid (AA) (37). Notably, many of the differentially elevated oxylipins were either derived from linoleic acid (LA) (8 of 21) or ALA (5 of 21) (Fig. 1), including nonenzymatic oxidation, lipoxygenase (LOX), cytochrome P450 (CYP450), and soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) metabolites (Fig. 1). Ratios of dihydroxy acids and their concordant epoxides, a measure of sEH activity, indicated no significant differences between the two cohorts (data not shown), suggesting an increased production of oxylipins via the P450/sEH pathway rather than a specific increase in sEH activity. When evaluating global abundances of class-specific oxylipins, circulating C18-diols, C22-diols, C18-epoxides, C18-hydroxy acids, and C18-ketones were elevated 1.8-, 1.5-, 1.4- 1.9-, and 1.6-fold in PH compared with control, respectively (Table 4).

Fig. 1.

Biochemical network displaying differences in lipid signaling mediators between pulmonary hypertension (PH) and non-PH. A biochemical network displaying metabolic differences in lipid signaling mediators is shown. Node shape represents the type of lipid mediator. Node color and size reflects significance (gray: not detected or measured; black: not significantly different; red: increased) and fold change in PH relative to control, respectively. Edge color represents relationship between nodes [blue: elongation/desaturation of fatty acid; green: enzymatic; yellow: nonenzymatic (oxidation)]. Edge labels indicate the enzyme or reaction that mediates the transformation. CBR1, carbonyl reductase 1; COX, cyclooxygenase; Cyp(epox), epoxygenase; DGLA, dihomo-γ-linolenic acid; GPx, glutathione peroxidase; LOX, lipoxygenase; LTA4, leukotriene A4; PGDH, 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase; PGS, prostaglandin synthase; sEH, soluble epoxide hydrolase.

In numerous samples, thromboxane B2 and 12-HETE values were greatly elevated (>10-fold median) in a subset of PH and control samples, suggesting platelet activation/degranulation either during preanalytical plasma handling or in these subjects (39). Therefore, we suspect that the data of these two metabolites may have been compromised and could not be reliably interpreted for this purpose in the study.

Subanalysis of associations between fetal circulating metabolites and BPD.

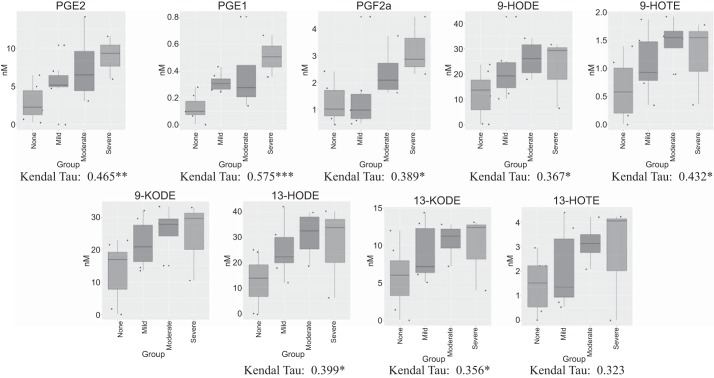

Given the heterogeneity of BPD status within our examined cohort, we aimed to determine whether putative associations between UCB metabolites and BPD presence and severity exist. For this analysis, only UCB from subjects that did not develop subsequent PH were considered. Using nonparametric correlations, we identified 47 metabolites that indicated significant associations with BPD status (Table 5). Notably, 8 of the 47 significantly associated metabolites were oxygenated lipids (Fig. 2) derived from cyclooxygenase (COX) AA metabolites (PGE1, PGE2, and PGF2α) or LOX and/or nonenzymatic LA products [9-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (HODE), 9-KODE, 13-HODE, and 13-KODE] and ALA products (9- and 13-HOTE).

Table 5.

Associations between cord blood plasma metabolites and BPD severity

| Compound | Kendal τ Correlation Coefficient | P Value | FDR-Adjusted PH | Direction of Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary metabolites with biogenic amines | ||||

| Erythritol | 0.4652 | 0.0049 | 0.2191 | Positive |

| Glucose-6-phosphate | 0.4323 | 0.0079 | 0.2615 | Positive |

| Aspartic acid | 0.4214 | 0.0081 | 0.2615 | Positive |

| Conduritol-β-epoxide | 0.4542 | 0.0100 | 0.2615 | Positive |

| Palmitoleic acid | 0.4542 | 0.0112 | 0.2639 | Positive |

| Xanthine | 0.3886 | 0.0131 | 0.2675 | Positive |

| Maltose | 0.4214 | 0.0214 | 0.3349 | Positive |

| Oleic acid | −0.4104 | 0.0218 | 0.3349 | Negative |

| Glycerol-α-phosphate | 0.3667 | 0.0267 | 0.3647 | Positive |

| Methylgalactose-NIST | −0.3995 | 0.0267 | 0.3647 | Negative |

| Proline | 0.3557 | 0.0270 | 0.3647 | Positive |

| Palmitic acid | −0.3776 | 0.0280 | 0.3671 | Negative |

| Piperidinobenzonitrile-NIST | −0.3119 | 0.0374 | 0.4350 | Negative |

| Phosphoethanolamine | 0.3338 | 0.0387 | 0.4350 | Positive |

| Hydroxylamine | −0.3338 | 0.0472 | 0.4877 | Negative |

| Niacinamide | 0.4761 | 0.0034 | 0.1881 | Positive |

| Urocanic acid | −0.4214 | 0.0159 | 0.2954 | Negative |

| Methyl histidine | −0.3119 | 0.0495 | 0.4877 | Negative |

| Complex lipids | ||||

| PE (p-36:4) or PE (o-36:5) | 0.5527 | 0.0003 | 0.0452 | Positive |

| TG (58:8) | −0.5637 | 0.0003 | 0.0452 | Negative |

| PE (p-38:4) or PE (o-38:5) | 0.4980 | 0.0010 | 0.1090 | Positive |

| TG (58:9) | −0.4980 | 0.0020 | 0.1399 | Negative |

| TG (60:11) | −0.4980 | 0.0020 | 0.1399 | Negative |

| TG (54:4) | −0.4871 | 0.0022 | 0.1399 | Negative |

| TG (54:3) | −0.3667 | 0.0089 | 0.2615 | Negative |

| TG (56:9) | −0.4323 | 0.0089 | 0.2615 | Negative |

| TG (56:8) A | −0.4104 | 0.0091 | 0.2615 | Negative |

| Ceramide (d34:1) | 0.4214 | 0.0099 | 0.2615 | Positive |

| TG (58:10) 1 | −0.4104 | 0.0112 | 0.2639 | Negative |

| TG (53:4) A | −0.3995 | 0.0125 | 0.2675 | Negative |

| TG (56:3) | −0.3776 | 0.0139 | 0.2697 | Negative |

| TG (56:4) | −0.3776 | 0.0181 | 0.3230 | Negative |

| TG (54:8) B | −0.3776 | 0.0228 | 0.3395 | Negative |

| PE (p-38:5) or PE (o-38:6) | 0.3338 | 0.0384 | 0.4350 | Positive |

| TG (58:10) | −0.3448 | 0.0407 | 0.4426 | Negative |

| SM (d34:2) | 0.3119 | 0.0495 | 0.4877 | Positive |

| Oxylipins | ||||

| PGE1 | 0.5746 | 0.0002 | 0.0452 | Positive |

| PGE2 | 0.4652 | 0.0046 | 0.2191 | Positive |

| 9-HOTE | 0.4323 | 0.0132 | 0.2675 | Positive |

| PGF2a | 0.3886 | 0.0210 | 0.3349 | Positive |

| 13-HODE | 0.3995 | 0.0214 | 0.3349 | Positive |

| 12,13-Ep-9-KODE | 0.3776 | 0.0303 | 0.3866 | Positive |

| 9-HODE | 0.3667 | 0.0334 | 0.4142 | Positive |

| 9-KODE | 0.3667 | 0.0390 | 0.4350 | Positive |

| 13-KODE | 0.3557 | 0.0468 | 0.4877 | Positive |

Associations were determined using Kendall τ correlation test. FDC, false discovery rate; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PH, pulmonary hypertension; SM, sphingomyelin; TG, triacylglyceride.

Fig. 2.

Associations between circulating metabolites in cord blood plasma and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) severity. Box and whisker plots are shown for respective metabolites based on subjects stratified by presence and severity of BPD. Associations were determined using the Kendall τ correlation test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Subanalysis of UCB from subjects with moderate to severe BPD.

To account for the potential effects of BPD status on our initial findings, we conducted an additional subanalysis on UCB samples from subjects with moderate to severe BPD who did (n = 18) or did not (n = 7) develop subsequent PH. Subanalysis identified PH-associated elevations in circulating nonadecanoic acid, whereas lysine, ornithine, phenylalanine, mannitol, phosphate, and niacinamide were decreased (Table 6). Alterations in metabolic products, including an increase in the glycolytic intermediate phosphoenolpyruvate and a decrease in N6,N6,N6,-trimethyl-l-lysine, a compound required for carnitine synthesis, may suggest differences in energy metabolism. None of the seven previously identified primary metabolites (Table 3) retained significance when comparing all subjects.

Table 6.

Significantly differential circulating metabolites and lipids that accompany development of PH based on subanalysis of subjects with moderate to severe BPD

| Compound | Domain | Controla | PH+ | Fold Changea | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary metabolites with biogenic amines | |||||

| Lysine | Amino acid | 63,500 ± 27,000 | 39,900 ± 21,000 | 0.63 | 0.0369 |

| N6,N6,N6-Trimethyl-l-lysine | Amino acid | 10,400 ± 4,200 | 5,240 ± 3,300 | 0.5 | 0.0322 |

| Ornithine* | Amino acid | 57.1 ± 12 | 38.7 ± 27 | 0.68 | 0.0154 |

| Phenylalanine | Amino acid | 138,000 ± 32,000 | 90,300 ± 65,000 | 0.65 | 0.0033 |

| Mannitol | Carbohydrate | 1,710 ± 870 | 869 ± 660 | 0.51 | 0.0307 |

| Nonadecanoic acid | Lipid | 183 ± 72 | 345 ± 190 | 1.89 | 0.0355 |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate | Organic acid | 82.2 ± 70 | 175 ± 94 | 2.13 | 0.0164 |

| Hydroxybutyric acid | Organic acid | 16,800 ± 5,000 | 8,240 ± 7,400 | 0.49 | 0.0178 |

| Phosphate | Other primary | 42,600 ± 17,000 | 23,200 ± 17,000 | 0.54 | 0.049 |

| Niacinamide | Vitamin | 63,600 ± 20,000 | 50,800 ± 39,000 | 0.8 | 0.0452 |

| Complex lipids | |||||

| CE (18:3) | Cholesterol ester | 4,990 ± 3,500 | 2,380 ± 1,500 | 0.48 | 0.0286 |

| CE (20:3) | Cholesterol ester | 10,900 ± 4,400 | 6,840 ± 3,000 | 0.63 | 0.0245 |

| CE (20:4) | Cholesterol ester | 97,700 ± 37,000 | 51,000 ± 27,000 | 0.52 | 0.0236 |

| Ceramide (d34:1) | Ceramide | 2,060 ± 730 | 768 ± 410 | 0.37 | 0.0039 |

| Ceramide (d40:1) | Ceramide | 2,110 ± 830 | 978 ± 460 | 0.46 | 0.0171 |

| Ceramide (d42:1) | Ceramide | 7,000 ± 4,800 | 3,480 ± 2,100 | 0.5 | 0.0422 |

| Ceramide (d42:2) | Ceramide | 3,140 ± 780 | 1,860 ± 930 | 0.59 | 0.0466 |

| Gal-Gal-Cer (d18:1/16:0) or lactosylceramide (d18:1/16:0) | Glucosyl ceramide | 29,300 ± 15,000 | 5,910 ± 4,400 | 0.2 | 1.00E-04 |

| PC (30:0) | Phospholipid | 173,000 ± 99,000 | 81,300 ± 49,000 | 0.47 | 0.044 |

| PC (38:4) A | Phospholipid | 1,190,000 ± 460,000 | 784,000 ± 580,000 | 0.66 | 0.0163 |

| PC (40:4) | Phospholipid | 26,900 ± 15,000 | 11,700 ± 7,200 | 0.43 | 0.0418 |

| PC (40:5) A | Phospholipid | 62,400 ± 41,000 | 19,900 ± 20,000 | 0.32 | 0.0108 |

| PC (o-32:0) | Phospholipid | 53,800 ± 33,000 | 16,700 ± 12,000 | 0.31 | 0.0201 |

| PC (p-32:0) or PC (o-32:1) | Phospholipid | 28,400 ± 16,000 | 12,200 ± 9,500 | 0.43 | 0.0328 |

| PC (p-34:1) or PC (o-34:2) A | Phospholipid | 10,500 ± 5,600 | 5,110 ± 3,600 | 0.49 | 0.043 |

| PC (p-36:2) or PC (o-36:3) | Phospholipid | 7,710 ± 3,900 | 3,400 ± 2,700 | 0.44 | 0.0167 |

| PC (p-36:3) or PC (o-36:4) | Phospholipid | 214,000 ± 130,000 | 67,900 ± 47,000 | 0.32 | 0.0207 |

| PC (p-36:4) or PC (o-36:5) | Phospholipid | 928 ± 370 | 543 ± 280 | 0.59 | 0.0084 |

| PC (p-38:2) or PC (o-38:3) | Phospholipid | 3,980 ± 2,800 | 1,160 ± 900 | 0.29 | 0.038 |

| PC (p-38:3) or PC (o-38:4) | Phospholipid | 34,600 ± 26,000 | 9,680 ± 7,400 | 0.28 | 0.0216 |

| PC (p-38:4) or PC (o-38:5) A | Phospholipid | 708 ± 440 | 358 ± 220 | 0.51 | 0.0294 |

| PC (p-38:4) or PC (o-38:5) A | Phospholipid | 92,400 ± 64,000 | 33,600 ± 25,000 | 0.36 | 0.0231 |

| PC (p-40:3) or PC (o-40:4) | Phospholipid | 4,030 ± 3,100 | 825 ± 650 | 0.2 | 0.0133 |

| PC (p-40:4) or PC (o-40:5) A | Phospholipid | 4,990 ± 3,500 | 1,210 ± 830 | 0.24 | 0.0011 |

| PC (p-40:5) or PC (o-40:6) | Phospholipid | 4,420 ± 3,100 | 1,990 ± 1,800 | 0.45 | 0.0187 |

| PC (p-40:7) or PC (o-40:8) | Phospholipid | 16,200 ± 9,900 | 6,240 ± 4,600 | 0.39 | 0.0261 |

| PC (p-42:4) or PC (o-42:5) | Phospholipid | 5,300 ± 4,400 | 779 ± 620 | 0.15 | 0.0002 |

| PC (p-44:4) or PC (o-44:5) | Phospholipid | 7,460 ± 5,900 | 1,590 ± 1,100 | 0.21 | 0.0249 |

| PE (p-36:4) or PE (o-36:5) | Phospholipid | 5,740 ± 2,300 | 3,340 ± 1,600 | 0.58 | 0.0164 |

| SM (d34:0) | Sphingomyelin | 110,000 ± 51,000 | 41,700 ± 28,000 | 0.38 | 0.0209 |

| SM (d34:1) | Sphingomyelin | 788,000 ± 330,000 | 323,000 ± 180,000 | 0.41 | 0.0465 |

| SM (d34:2) | Sphingomyelin | 121,000 ± 49,000 | 46,600 ± 26,000 | 0.39 | 0.0207 |

| SM (d36:0) | Sphingomyelin | 81,600 ± 36,000 | 38,300 ± 23,000 | 0.47 | 0.0462 |

| SM (d36:1) | Sphingomyelin | 225,000 ± 110,000 | 101,000 ± 69,000 | 0.45 | 0.0422 |

| SM (d38:0) | Sphingomyelin | 14,500 ± 7,800 | 6,480 ± 3,700 | 0.45 | 0.042 |

| SM (d38:1) | Sphingomyelin | 50,500 ± 24,000 | 24,800 ± 16,000 | 0.49 | 0.0383 |

| SM (d39:1) | Sphingomyelin | 4,550 ± 2,600 | 2,370 ± 1,800 | 0.52 | 0.0366 |

| SM (d40:1) | Sphingomyelin | 115,000 ± 54,000 | 38,700 ± 25,000 | 0.34 | 0.0143 |

| SM (d40:2) A | Sphingomyelin | 77,000 ± 56,000 | 32,800 ± 27,000 | 0.43 | 0.0342 |

| SM (d41:1) | Sphingomyelin | 12,600 ± 8,000 | 5,070 ± 4,200 | 0.4 | 0.0348 |

| SM (d41:2) | Sphingomyelin | 749 ± 290 | 365 ± 190 | 0.49 | 0.0189 |

| SM (d42:2) A | Sphingomyelin | 441,000 ± 220,000 | 150,000 ± 84,000 | 0.34 | 0.0317 |

| TG (53:4) A | Triacylglyceride | 2,820 ± 3,000 | 8,670 ± 6,300 | 3.07 | 0.0414 |

| Oxylipins | |||||

| 19,20-DiHDoPE | Diol | 1.54 ± 1.5 | 3.28 ± 2.1 | 2.13 | 0.0275 |

Values are means ± SD. Primary metabolites, biogenic amines, and complex lipids are reported as relative peak heights, oxylipins are reported as concentrations (nM). PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PH, pulmonary hypertension; SM, sphingomyelin; TG, triacylglyceride.

Fold change of PH/control,

significance was determined by two-sided t-test or Welch t-test, depending on individual analyte normality, and

nM concentrations.

Alterations in complex lipids remained consistent with our observations from the initial analysis. Significant reductions in several choline-containing phospholipids and elevations in FFAs and a TG (53:4) were characteristic of UCB from preterm infants who developed subsequent PH (Table 6). Cholesterol esters, nonesterified ceramides, and glucosyl-ceramides were also found to be significantly reduced in the PH group relative to controls (Table 6). These findings suggest that the observed reduction in UCB structural lipids, particularly choline-containing phospholipids, and elevation in FFAs and select TGs are more closely related to PH than BPD.

It is interesting to note that many of the identified oxylipins that were significantly different when including all subjects failed to retain significance in our subanalysis. The lone exception was the docosahexaenoic acid metabolite 19,20-DiHDoPE, which was elevated in the PH cohort (Table 6). This would suggest that the elevation in aforementioned oxylipins are more strongly linked to development and progression of BPD rather than PH, a notion that is supported by the observations that many of the oxylipins were also positively associated with BPD status (Fig. 2).

Validation of PH-associated complex lipids in infants with moderate-severe BPD.

To validate our above-mentioned findings, we performed metabolomic analyses on an independent cohort consisting of 10 cases and 10 controls. Importantly, our validation cohort was matched for BPD status (moderate-severe only), thereby removing potential bias because of the presence or severity of BPD. To this end, we focused our analyses on complex lipids on the basis that lipid species, particularly choline-containing lipids, remained statistically different between cases and controls in the discovery cohort, even when taking into account the severity of BPD. Consistent with our initial findings, choline-containing lipid species were significantly reduced in cases relative to controls in the validation cohort (Table 7).

Table 7.

Validation cohort PH-associated perturbations in major structural lipids

| Lipid Domain* | PH− | PH+ | Fold Change§ | P Value¶ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcarnitines (7)† | 221,017 ± 52,356 | 183,407 ± 58,724 | 0.83 | 0.07 |

| Ceramides (24) | 385,211 ± 125,023 | 303,119 ± 107,469 | 0.79 | 0.1 |

| Cholesterol esters (14) | 7,912,370 ± 2,533,645 | 6,128,807 ± 2,474,167 | 0.77 | 0.08 |

| Diacylglycerols (8) | 56,515 ± 32,009 | 54,225 ± 47,990 | 0.96 | 0.1 |

| Free fatty acids (14) | 889,692 ± 406,594 | 708,626 ± 275,991 | 0.80 | 0.2 |

| Glycosphingolipids (10) | 133,211 ± 36,978 | 88,011 ± 33,673 | 0.66 | 0.0011 |

| Lysophatidylcholines (27) | 7,318,071 ± 3,117,915 | 5,376,811 ± 2,473,810 | 0.73 | 0.1 |

| Lysophosphatidylethanolamines (7) | 70,619 ± 25,357 | 52,895 ± 21,757 | 0.75 | 0.1 |

| Phosphatidylcholines (109) | 100,659,668 ± 13,666,756 | 87,323,531 ± 21,838,007 | 0.87 | 0.06 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (11) | 331,513 ± 138,258 | 253,044 ± 121,819 | 0.76 | 0.032 |

| PlasmalogenLPCs (3) | 55,573 ± 15,446 | 41,833 ± 14,677 | 0.75 | 0.022 |

| PlasmalogenPCs (49) | 4,175,912 ± 1,377,918 | 3,018,397 ± 1,455,014 | 0.72 | 0.038 |

| PlasmalogenPEs (17) | 116,166 ± 36,730 | 92,079 ± 37,669 | 0.79 | 0.045 |

| Sphingomyelins (70) | 23,282,302 ± 5,034,895 | 16,654,834 ± 6,006,540 | 0.72 | 0.0093 |

| Triacylglycerols (97) | 26,734,745 ± 14,799,333 | 26,729,596 ± 15,701,640 | 1.00 | 0.5 |

Values (means ± SD) represent the summed intensities of individual annotated lipids belonging to the respective lipid class. Complex lipids are presented as summed peak intensities. PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PH, pulmonary hypertension.

Major lipid classes,

number of measured molecules,

fold change of PH+/PH−, and

significance was determined by one-sided Mann-Whitney U-test.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, a combined metabolomics approach consisting of an untargeted analysis of primary metabolites and complex lipids coupled with a targeted analysis of biogenic amines and lipid signaling mediators identified 1,656 metabolic features, 407 with known structures, in UCB plasma of preterm infants who later developed PH compared with those who did not. To our knowledge, this is the first study to expansively evaluate the systemic alterations in the metabolic profiles of cord blood plasma from preterm infants that precede development of BPD-associated PH. Overall, the observed changes implicate lipid signaling, lipid biosynthesis, and oxidative stress as cofactors associated with the onset of PH in preterm infants.

Although UBC is most commonly acquired for use of its rich stem cell content, it also contains the nutrients and metabolites that may provide insight into the events occurring during fetal growth and help predict the development of disease after birth (31). In relationship to many of our untargeted analysis metabolites investigated, nutrient metabolism and delivery to the fetus are known to be altered by the placenta during pregnancy (11). Furthermore, potentially related to our oxylipin analysis, the placenta expresses phospholipase A2 and lipoprotein lipase (27) in addition to COX, LOX, and CYP450 (47).

Rodent studies have found associations between BPD and early increases in COX-2 and 5-LOX metabolites (44). Previous metabolomics studies have identified select sugar and amine derivatives in late gestation amniotic fluid and urine collected at or near birth of preterm infants with BPD (19, 41), as well as phospholipids in exhaled breath condensate of adolescent BPD patients (13). Specific long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid phospholipids in UCB have also been identified as potential predictors of BPD, particularly in infants born at less than 28 wk of gestation (6). A previous study of lipid metabolites in the first 3 days of life in 272 premature infants found higher absolute levels of several HETEs in infants who developed BPD, although these differences became nonsignificant when adjusting for gestational age (45). Serum phospholipids were higher in premature infants than samples of UCB from infants matched for gestational age, predominantly because of increases in LA-containing PC and phosphatidylethanolamine (6). Serum choline levels decrease dramatically from UCB levels within 48 h of birth in preterm infants but not in term infants (8). Combined, these previous observations suggest immaturity in lipid metabolism in preterm infants that is likely exacerbated by the abrupt loss of maternal/placental regulation and the challenges associated with current enteral and parenteral nutritional approaches for extremely preterm infants (high in LA, low in choline).

This study focused on a comprehensive analysis of cord blood as a potential marker of PH risk. When considering all subjects, striking differences in the UCB composition of complex lipids and lipid mediators were observed in neonates who did not develop subsequent PH. Analysis of the lipidome indicated that UCB plasma from PH-positive infants had lower circulating PCs and SMs and elevated choline. These findings were confirmed in an independent cohort of UCB plasma from cases and controls providing confidence in our initial findings. These findings are also consistent with a growth-restriction induced PH rat model, where we recently reported substantial reductions in plasma PC levels in rats that developed PH as compared with controls (34). Moreover, these circulating phospholipids appear to be a primary product of placental metabolism, with fetal lipoprotein metabolism maturing late in the neonatal period of normal pregnancies (29). Phospholipid metabolism is directly linked to the physiological production of pulmonary surfactants that are 70–80% PCs. The late maturation of PC biosynthesis is a well-known risk marker and contributor for BPD development and PH emergence (1), and administration of the PC precursor CDP-choline attenuated hyperoxia-induced lung damage in a neonatal model of BPD (14). In our cohort, circulating levels of choline were higher in the PH positive group. Notably, when evaluating only moderate to severe BPD subjects stratified by PH status, we retained the significant PH-associated reductions in the aforementioned choline-containing phospholipids in addition to reductions in cholesterol esters, nonesterified ceramides, and glucosylceramides. However, choline was not significantly different in the subanalysis; instead, choline tended to be positively associated with BPD presence and severity (Table 4), consistent with previous findings (14).

Despite the potential role for disruption of nitric oxide synthase function (2, 22, 40), we did not observe circulating differences in arginine, citrulline, or ornithine between the PH-positive and -negative groups when including all subjects. However, if only moderate to severe BPD subjects were considered, ornithine concentrations were reduced 1.5-fold in the PH group (data not shown). Moreover, the ratio of citrulline-to-ornithine tended to be higher in the PH group relative to the non-PH group (0.41 ± 0.70 vs. 0.15 ± 0.07; P value: 0.147), suggesting an increase in NO production.

A subanalysis to investigate metabolites associated with BPD severity revealed a strong positive correlation with numerous COX-derived prostaglandins and 5- or 15-LOX-derived LA hydroxy acids and ketones. Interestingly, the positively correlated PGE2 and PGE1 have been shown to be secreted by the placenta to maintain prenatal patency of the ductus arteriosus (23). Persistence of a moderate to large ductus arteriosus following birth is a risk factor for BPD. Furthermore, the previously mentioned hydroxy acids and ketones are associated with placental signaling via activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)γ (10, 35, 61). Specifically, 9- and 13-HODE, and 13-oxo-ODE are putative ligands of PPARγ, the expression of which, in the placenta, has been shown to be vital for proper cardiac tissue development (3) and implicated in the regulation of PH development (55). While these PPARγ ligand oxylipins are typically produced by LOX in a controlled manner, they can be produced nonenzymatically during disease processes when oxidative stress is increased (60). As a result, in these conditions, they are associated with elevated inflammation, apoptosis, and vasoconstriction via GPR132 (G2A) receptor activation by 9-HODE and 9-HpODE and transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 and CD36 activation by 13-HODE (33, 36, 60). Furthermore, we observed PH-associated elevations in 9-HETE, a nonenzymatic oxidation product of AA and previously noted marker of oxidative stress and disease (50). Oxidative stress is heavily implicated in the etiology of both BPD and PH, facilitating alterations in the pulmonary vasculature and right ventricle and decoupling endothelial nitric oxide synthase (16).

CYP450-derived fatty acid epoxides and sEH-derived dihydroxy fatty acids have been observed in the placenta previously and are associated with altered uteroplacental remodeling (26). We observed changes in CYP2 epoxygenated and dihydroxy acid linoleate and alpha linolenate-derived oxylipins, including 9,10-EpOME 15,16-EpODE; 9,10-DiHOME; 12,13-DiHOME; 14,15-DiHETE; 15,16-DiODE; and 9,10-DiODE. When evaluating the ratio of the respective dihydroxy acids to their parent epoxides, no significant differences were found between the PH and non-PH group, collectively suggesting this was an increase in both P450 and sEH activity. Regardless, research indicates that linoleate epoxygenated and dihydroxy acid forms may be involved in a variety of biological processes from promotion of neutrophil accumulation, respiratory burst, and pulmonary edema to proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells and vascularization (21, 56, 58). Respiratory burst and pulmonary edema are associated with PH and BPD, respectively (12, 46).

An additional subanalysis was conducted in moderate-severe BPD subjects who did or did not develop PH to better differentiate observed alterations that were more associated with BPD versus those that were more associated with PH. Interestingly, all of the lipidomic alterations in terms of reduced PCs and SMs remained statistically significant. Furthermore, decreases in total ceramides and plasmalogen PCs were observed. These findings were recapitulated in our validation cohort of BPD status-matched cases and controls. All of these support the previous discussion regarding their role in PH development.

Our findings collectively demonstrate dyslipidemia in UCB plasma from preterm infants who go on to develop PH. This dyslipidemia is predominately characterized by reductions in circulating choline-containing phospholipids. Consequently, these findings may have value for characterizing cord blood metabolites associated with preterm infants who are at risk for developing PH. We acknowledge that the sample sizes for our cohorts are small; however, it must be emphasized that 1) accessibility to UCB plasma of premature infants diagnosed with BPD that do or do not develop subsequent PH is limited and 2) despite sample size limitations, we were able to confirm that choline-containing phospholipids are reduced in UCB plasma of cases relative to controls in an independent validation cohort, providing confidence in our initial findings.

Larger studies with analysis including both gestational age and BPD severity will be required to fully evaluate the diagnostic value of altered lipid profiles in the context of PH development. While the groups were well matched by gestational age and there were balanced proportions of infant sex difference and low birth status, it must be noted that the data were not adjusted for any of the other numerous prenatal and postnatal factors that influence the development of BPD and PH, including oligohydramnios, maternal preeclampsia, obesity, diabetes, corticosteroid administration, and cesarean section delivery, and neonatal pulmonary abnormalities, among numerous others (32, 42). A larger sample will be needed to take into account these and other important covariates of extremely preterm birth. Due to the possible influence of maternal characteristics on metabolite differences observed in the UCB (7), future studies that concurrently analyze maternal plasma would be optimal.

In conclusion, UCB plasma from preterm infants that did or did not develop BPD-associated PH was characterized by states of dyslipidemia and suggest metabolic immaturity, associated with deficiencies in lipids critical for proper growth and development. Specifically, preterm infants that developed PH displayed reductions in major choline-containing phospholipids and elevations in choline, suggesting alterations in PC biosynthesis. BPD severity was largely characterized by alterations in oxylipin concentrations. UCB reductions in choline-containing phospholipids hold promise as early screening markers for development of BPD-associated PH in preterm infants.

GRANTS

This research is funded by National Institutes of Heath (NIH) Grants U24-DK-097154 (to O. Fiehn) and K23-HL-093302 (to K. Mestan), with instrument support by S10-RR-031630 (to O. Fiehn) and by US Department of Agriculture Intramural Project 2032-51530-022-00D (to J. W. Newman).

DISCLAIMERS

The US Department of Agriculture is an equal opportunity employer and provider.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.M., R.H.S., and S.W. conceived and designed research; K.M. and R.H.S. performed experiments; M.R.L.F., J.F.F., and D.G. analyzed data; M.R.L.F., J.F.F., J.W.N., and S.W. interpreted results of experiments; M.R.L.F. and J.F.F. prepared figures; M.R.L.F. and J.F.F. drafted manuscript; M.R.L.F., J.F.F., D.G., T.L.P., J.W.N., O.F., M.A.U., K.M., R.H.S., and S.W. edited and revised manuscript; M.R.L.F., J.F.F., D.G., T.L.P., J.W.N., O.F., M.A.U., K.M., R.H.S., and S.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ENDNOTE

At the request of the authors, readers are herein alerted to the fact that additional materials related to this manuscript may be found at https://doi.org/10.21228/M8N30T on the NIH Metabolomics Workbench data repository (project PR000207). These materials are not a part of this manuscript and have not undergone peer review by the American Physiological Society (APS). APS and the journal editors take no responsibility for these materials, for the Web site address, or for any links to or from it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of T. L. Pedersen: Advanced Analytics, 118 First St., Woodland, CA 95695.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akella A, Deshpande SB. Pulmonary surfactants and their role in pathophysiology of lung disorders. Indian J Exp Biol 51: 5–22, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Askie LM, Ballard RA, Cutter GR, Dani C, Elbourne D, Field D, Hascoet JM, Hibbs AM, Kinsella JP, Mercier JC, Rich W, Schreiber MD, Wongsiridej PS, Subhedar NV, Van Meurs KP, Voysey M, Barrington K, Ehrenkranz RA, Finer NN; Meta-analysis of Preterm Patients on Inhaled Nitric Oxide Collaboration . Inhaled nitric oxide in preterm infants: an individual-patient data meta-analysis of randomized trials. Pediatrics 128: 729–739, 2011. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell 4: 585–595, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57: 289–290, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkelhamer SK, Mestan KK, Steinhorn RH. Pulmonary hypertension in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Perinatol 37: 124–131, 2013. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernhard W, Raith M, Koch V, Kunze R, Maas C, Abele H, Poets CF, Franz AR. Plasma phospholipids indicate impaired fatty acid homeostasis in preterm infants. Eur J Nutr 53: 1533–1547, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernhard W, Raith M, Koch V, Maas C, Abele H, Poets CF, Franz AR. Developmental changes in polyunsaturated fetal plasma phospholipids and feto-maternal plasma phospholipid ratios and their association with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Eur J Nutr 55: 2265–2274, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-1036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernhard W, Raith M, Kunze R, Koch V, Heni M, Maas C, Abele H, Poets CF, Franz AR. Choline concentrations are lower in postnatal plasma of preterm infants than in cord plasma. Eur J Nutr 54: 733–741, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0751-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhat R, Salas AA, Foster C, Carlo WA, Ambalavanan N. Prospective analysis of pulmonary hypertension in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 129: e682–e689, 2012. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borel V, Gallot D, Marceau G, Sapin V, Blanchon L. Placental implications of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in gestation and parturition. PPAR Res 2008: 758562, 2008. doi: 10.1155/2008/758562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brett KE, Ferraro ZM, Yockell-Lelievre J, Gruslin A, Adamo KB. Maternal-fetal nutrient transport in pregnancy pathologies: the role of the placenta. Int J Mol Sci 15: 16153–16185, 2014. doi: 10.3390/ijms150916153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown ER, Stark A, Sosenko I, Lawson EE, Avery ME. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: possible relationship to pulmonary edema. J Pediatr 92: 982–984, 1978. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(78)80382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Čajka T, Fiehn O. Increasing lipidomic coverage by selecting optimal mobile-phase modifiers in LC–MS of blood plasma. Metabolomics 12: 1–11, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s11306-015-0929-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carraro S, Giordano G, Pirillo P, Maretti M, Reniero F, Cogo PE, Perilongo G, Stocchero M, Baraldi E. Airway metabolic anomalies in adolescents with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: new insights from the metabolomic approach. J Pediatr 166: 234–239.e1, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cetinkaya M, Cansev M, Kafa IM, Tayman C, Cekmez F, Canpolat FE, Tunc T, Sarici SU. Cytidine 5′-diphosphocholine ameliorates hyperoxic lung injury in a neonatal rat model. Pediatr Res 74: 26–33, 2013. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Check J, Gotteiner N, Liu X, Su E, Porta N, Steinhorn R, Mestan KK. Fetal growth restriction and pulmonary hypertension in premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Perinatol 33: 553–557, 2013. doi: 10.1038/jp.2012.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeMarco VG, Whaley-Connell AT, Sowers JR, Habibi J, Dellsperger KC. Contribution of oxidative stress to pulmonary arterial hypertension. World J Cardiol 2: 316–324, 2010. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v2.i10.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doyle LW, Anderson PJ. Long-term outcomes of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 14: 391–395, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fahrmann J, Grapov D, Yang J, Hammock B, Fiehn O, Bell GI, Hara M. Systemic alterations in the metabolome of diabetic NOD mice delineate increased oxidative stress accompanied by reduced inflammation and hypertriglyceremia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 308: E978–E989, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00019.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fanos V, Pintus MC, Lussu M, Atzori L, Noto A, Stronati M, Guimaraes H, Marcialis MA, Rocha G, Moretti C, Papoff P, Lacerenza S, Puddu S, Giuffrè M, Serraino F, Mussap M, Corsello G. Urinary metabolomics of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD): preliminary data at birth suggest it is a congenital disease. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 27, Suppl 2: 39–45, 2014. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.955966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiehn O, Wohlgemuth G, Scholz M. Setup and annotation of metabolomic experiments by integrating biological and mass spectrometric metadata. Data Integr Life Sci Proc 3615: 224–239, 2005. doi: 10.1007/11530084_18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleming I. The pharmacology of the cytochrome P450 epoxygenase/soluble epoxide hydrolase axis in the vasculature and cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol Rev 66: 1106–1140, 2014. doi: 10.1124/pr.113.007781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gadhia MM, Cutter GR, Abman SH, Kinsella JP. Effects of early inhaled nitric oxide therapy and vitamin A supplementation on the risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature newborns with respiratory failure. J Pediatr 164: 744–748, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gournay V. The ductus arteriosus: physiology, regulation, and functional and congenital anomalies. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 104: 578–585, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grapov D, Adams SH, Pedersen TL, Garvey WT, Newman JW. Type 2 diabetes associated changes in the plasma non-esterified fatty acids, oxylipins and endocannabinoids. PLoS One 7: e48852, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grapov D, Wanichthanarak K, Fiehn O. MetaMapR: pathway independent metabolomic network analysis incorporating unknowns. Bioinformatics 31: 2757–2760, 2015. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herse F, Lamarca B, Hubel CA, Kaartokallio T, Lokki AI, Ekholm E, Laivuori H, Gauster M, Huppertz B, Sugulle M, Ryan MJ, Novotny S, Brewer J, Park JK, Kacik M, Hoyer J, Verlohren S, Wallukat G, Rothe M, Luft FC, Muller DN, Schunck WH, Staff AC, Dechend R. Cytochrome P450 subfamily 2J polypeptide 2 expression and circulating epoxyeicosatrienoic metabolites in preeclampsia. Circulation 126: 2990–2999, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.127340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jadoon A, Cunningham P, McDermott LC. Arachidonic acid metabolism in the human placenta: identification of a putative lipoxygenase. Placenta 35: 422–424, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163: 1723–1729, 2001. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.2011060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kilby MD, Neary RH, Mackness MI, Durrington PN. Fetal and maternal lipoprotein metabolism in human pregnancy complicated by type I diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 1736–1741, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kind T, Liu KH, Lee DY, DeFelice B, Meissen JK, Fiehn O. LipidBlast in silico tandem mass spectrometry database for lipid identification. Nat Methods 10: 755–758, 2013. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kluth SM, Radke TF, Kogler G. Potential application of cord blood-derived stromal cells in cellular therapy and regenerative medicine. J Blood Transfus 2012: 365182, 2012. doi: 10.1155/2012/365182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konduri GG, Kim UO. Advances in the diagnosis and management of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatr Clin North Am 56: 579–600, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuda O, Jenkins CM, Skinner JR, Moon SH, Su X, Gross RW, Abumrad NA. CD36 protein is involved in store-operated calcium flux, phospholipase A2 activation, and production of prostaglandin E2. J Biol Chem 286: 17785–17795, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.232975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.La Frano MR, Fahrmann JF, Grapov D, Fiehn O, Pedersen TL, Newman JW, Underwood MA, Steinhorn RH, Wedgwood S. Metabolic perturbations of postnatal growth restriction and hyperoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in a bronchopulmonary dysplasia model. Metabolomics 13: 32, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11306-017-1170-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leghmar K, Cenac N, Rolland M, Martin H, Rauwel B, Bertrand-Michel J, Le Faouder P, Bénard M, Casper C, Davrinche C, Fournier T, Chavanas S. Cytomegalovirus infection triggers the secretion of the PPARγ agonists 15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE) and 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid (13-HODE) in human cytotrophoblasts and placental cultures. PLoS One 10: e0132627, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mabalirajan U, Rehman R, Ahmad T, Kumar S, Singh S, Leishangthem GD, Aich J, Kumar M, Khanna K, Singh VP, Dinda AK, Biswal S, Agrawal A, Ghosh B. Linoleic acid metabolite drives severe asthma by causing airway epithelial injury. Sci Rep 3: 1349, 2013. doi: 10.1038/srep01349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mallat Z, Nakamura T, Ohan J, Lesèche G, Tedgui A, Maclouf J, Murphy RC. The relationship of hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids and F2-isoprostanes to plaque instability in human carotid atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest 103: 421–427, 1999. doi: 10.1172/JCI3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mirza H, Ziegler J, Ford S, Padbury J, Tucker R, Laptook A. Pulmonary hypertension in preterm infants: prevalence and association with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 165: 909–14.e1, 2014. [Erratum in J Pediatr 166: 782, 2015]. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Donnell VB, Murphy RC, Watson SP. Platelet lipidomics: modern day perspective on lipid discovery and characterization in platelets. Circ Res 114: 1185–1203, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson DL, Dawling S, Walsh WF, Haines JL, Christman BW, Bazyk A, Scott N, Summar ML. Neonatal pulmonary hypertension–urea-cycle intermediates, nitric oxide production, and carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase function. N Engl J Med 344: 1832–1838, 2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106143442404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pintus MC, Lussu M, Dessì A, Pintus R, Noto A, Masile V, Marcialis MA, Puddu M, Fanos V, Atzori L. Urinary 1 H-NMR metabolomics in the first week of life can anticipate BPD. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018: 7620671, 2018. doi: 10.1155/2018/7620671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puthiyachirakkal M, Mhanna MJ. Pathophysiology, management, and outcome of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: a clinical review. Front Pediatr 1: 23, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fped.2013.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robbins IM, Moore TM, Blaisdell CJ, Abman SH. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Workshop: improving outcomes for pulmonary vascular disease. Circulation 125: 2165–2170, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.092924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogers LK, Tipple TE, Britt RD, Welty SE. Hyperoxia exposure alters hepatic eicosanoid metabolism in newborn mice. Pediatr Res 67: 144–149, 2010. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181c2df4f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rogers LK, Young CM, Pennell ML, Tipple TE, Leonhart KL, Welty SE. Plasma lipid metabolites are associated with gestational age but not bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Acta Paediatr 101: e321–e326, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose F, Hattar K, Gakisch S, Grimminger F, Olschewski H, Seeger W, Tschuschner A, Schermuly RT, Weissmann N, Hanze J, Sibelius U, Ghofrani HA. Increased neutrophil mediator release in patients with pulmonary hypertension–suppression by inhaled iloprost. Thromb Haemost 90: 1141–1149, 2003. doi: 10.1160/TH03-03-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schäfer WR, Zahradnik HP, Arbogast E, Wetzka B, Werner K, Breckwoldt M. Arachidonate metabolism in human placenta, fetal membranes, decidua and myometrium: lipoxygenase and cytochrome P450 metabolites as main products in HPLC profiles. Placenta 17: 231–238, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4004(96)90043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scholz M, Fiehn O. SetupX–a public study design database for metabolomic projects. Pac Symp Biocomput 2007: 169–180, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res 13: 2498–2504, 2003. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shishehbor MH, Zhang R, Medina H, Brennan ML, Brennan DM, Ellis SG, Topol EJ, Hazen SL. Systemic elevations of free radical oxidation products of arachidonic acid are associated with angiographic evidence of coronary artery disease. Free Radic Biol Med 41: 1678–1683, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slaughter JL, Pakrashi T, Jones DE, South AP, Shah TA. Echocardiographic detection of pulmonary hypertension in extremely low birth weight infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia requiring prolonged positive pressure ventilation. J Perinatol 31: 635–640, 2011. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spratlin JL, Serkova NJ, Eckhardt SG. Clinical applications of metabolomics in oncology: a review. Clin Cancer Res 15: 431–440, 2009. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strassburg K, Huijbrechts AM, Kortekaas KA, Lindeman JH, Pedersen TL, Dane A, Berger R, Brenkman A, Hankemeier T, van Duynhoven J, Kalkhoven E, Newman JW, Vreeken RJ. Quantitative profiling of oxylipins through comprehensive LC-MS/MS analysis: application in cardiac surgery. Anal Bioanal Chem 404: 1413–1426, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6226-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sud M, Fahy E, Cotter D, Azam K, Vadivelu I, Burant C, Edison A, Fiehn O, Higashi R, Nair KS, Sumner S, Subramaniam S. Metabolomics workbench: an international repository for metabolomics data and metadata, metabolite standards, protocols, tutorials and training, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 44: D463–D470, 2016. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sutliff R, Kang B, Hart C. PPARgamma as a potential therapeutic target in pulmonary hypertension. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 4: 143–160, 2010. doi: 10.1177/1753465809369619. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=23148150&dopt=Abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thompson DA, Hammock BD. Dihydroxyoctadecamonoenoate esters inhibit the neutrophil respiratory burst. J Biosci 32: 279–291, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s12038-007-0028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Totani Y, Saito Y, Ishizaki T, Sasaki F, Ameshima S, Miyamori I. Leukotoxin and its diol induce neutrophil chemotaxis through signal transduction different from that of fMLP. Eur Respir J 15: 75–79, 2000. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.15107500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsugawa H, Cajka T, Kind T, Ma Y, Higgins B, Ikeda K, Kanazawa M, VanderGheynst J, Fiehn O, Arita M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat Methods 12: 523–526, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vangaveti V, Baune BT, Kennedy RL. Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids: novel regulators of macrophage differentiation and atherogenesis. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 1: 51–60, 2010. doi: 10.1177/2042018810375656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vázquez JK, Fajardo ME, Malacara JM, Ramírez J, Pérez EL, Aguilar H. Placental PPAR-Gamma Expression Correlates with Cord Blood Triglyceride in Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Endocrine Society's 96th Annual Meeting and Expo, June 21–24, Chicago: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voller SB, Chock S, Ernst LM, Su E, Liu X, Farrow KN, Mestan KK. Cord blood biomarkers of vascular endothelial growth (VEGF and sFlt-1) and postnatal growth: a preterm birth cohort study. Early Hum Dev 90: 195–200, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wikoff WR, Grapov D, Fahrmann JF, DeFelice B, Rom WN, Pass HI, Kim K, Nguyen U, Taylor SL, Gandara DR, Kelly K, Fiehn O, Miyamoto S. Metabolomic markers of altered nucleotide metabolism in early stage adenocarcinoma. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 8: 410–418, 2015. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]