Abstract

Infantile strabismus is a common disorder characterized by a chronic misalignment of the eyes, impairment of binocular vision, and oculomotor abnormalities. Nonhuman primates with strabismus, induced in infancy, show a pattern of abnormalities similar to those of strabismic children. This allows strabismic nonhuman primates to serve as an ideal animal model to examine neural mechanisms associated with aberrant oculomotor behavior. Here, we test the hypothesis that impairment of disparity vergence and horizontal saccade disconjugacy in exotropia and esotropia are associated with disrupted tuning of near- and far-response neurons in the supraoculomotor area (SOA). In normal animals, these neurons carry signals related to vergence position and/or velocity. We hypothesized that, in strabismus, these neurons modulate inappropriately in association with saccades between equidistant targets. We recorded from 62 SOA neurons from 4 strabismic animals (2 esotropes and 2 exotropes) during visually guided saccades to a target that stepped to different locations on a tangent screen. Under these same conditions, SOA neurons in normal animals show no detectable modulation. In our strabismic subjects, we found that a subset of SOA neurons carry weak vergence velocity signals during saccades. In addition, a subset of SOA neurons showed clear modulation associated with slow fluctuations of horizontal strabismus angle in the absence of a saccade. We suggest that abnormal SOA activity contributes to fixation instability but plays only a minor role in the horizontal disconjugacy of saccades that do not switch fixation from one eye to the other.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The present study is the first to investigate the activity of neurons in the supraoculomotor area (SOA) during horizontally disconjugate saccades in a nonhuman primate model of infantile strabismus. We report that fluctuations of horizontal strabismus angle, during fixation of static targets on a tangent screen, are associated with contextually inappropriate modulation of SOA activity. However, firing rate modulation during saccades is too weak to make a major contribution to horizontal disconjugacy.

Keywords: esotropia, monkey, neurophysiology, strabismus, vergence

INTRODUCTION

Numerous studies have reported similar abnormalities of saccades in human patients with strabismus (Bucci et al. 2002; Ghasia et al. 2015; Kapoula et al. 1997; Maxwell et al. 1995) and in monkeys with experimentally induced strabismus (Fu et al. 2007; Walton et al. 2014). Of particular interest in the present study is the observation that horizontal saccade amplitude typically differs for the two eyes. Studies employing a nonhuman primate model of the disorder have provided compelling evidence that this abnormality is associated with abnormalities in saccade-related areas of brain stem (Fleuriet et al. 2016; Upadhyaya et al. 2017a; Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2013).

Given the chronic misalignment of the eyes that characterizes infantile strabismus syndrome, it should not be surprising that vergence eye movements are severely impaired in both human patients (Kenyon et al. 1980, 1981) and in monkeys with experimentally induced strabismus (Tychsen and Scott 2003). In normal monkeys, the tonic firing rates of near-response neurons in the supraoculomotor area (SOA) increase with convergence (Mays 1984; Zhang et al. 1992). In monkeys with experimentally induced exotropia, these same neurons modulate in association with changes in horizontal strabismus angle that accompany switches of the fixating eye but with reduced sensitivity (Das 2012). A reduced convergence drive would, presumably, contribute to the horizontal misalignment of the eyes in exotropia. To our knowledge, near-response cells have never been recorded in esotropia. Both infantile esotropia and infantile exotropia are associated with a loss of binocular visual responses in cortex [for 2 recent reviews, see Das (2016) and Walton et al. (2017)]. Since binocular disparity is one of the major sensory signals driving vergence eye movements, one might predict that near-response cells should show a weaker modulation with horizontal strabismus angle in both esotropia and exotropia compared with the vergence position sensitivity in normal monkeys (hypothesis 1). If this is the case, then the basic, underlying cause of the horizontal misalignment would be something other than abnormal SOA activity in esotropia. With these considerations in mind, one goal of the present study was to compare the vergence position sensitivities of SOA neurons in normal, esotropic, and exotropic monkeys.

When acuity is good in both eyes, subjects with strabismus can fixate targets with either eye and often switch between the two. As noted above, neurons in SOA encode changes in horizontal strabismus angle associated with fixation switches (dissociated horizontal deviation) in monkeys with exotropia (Das 2011, 2012). During smooth pursuit of targets moving vertically on a tangent screen, however, these neurons did not modulate for changes in horizontal strabismus angle associated with pattern strabismus. Generalizing this result to a saccade task on a tangent screen, we predicted that the firing rates of SOA neurons would not modulate in association with changes in horizontal strabismus angle that result from horizontally disconjugate saccades in the absence of a fixation switch (hypothesis 2a). Alternatively, the absence of normal binocular disparity signals and the presence of abnormal monocular signals in visual cortex (Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017) might leave the vergence system unable to determine when it should make a contribution to a gaze shift. In this case, SOA neurons might carry contextually inappropriate vergence position and/or velocity signals associated with saccades between equidistant targets (hypothesis 2b). In the present study, we test these competing hypotheses by recording single-unit activity of SOA neurons in four monkeys with experimentally induced strabismus while they used saccades to track a target on a tangent screen.

Fixation stability is crucial to normal visual perception (Amore et al. 2013). A recent study has reported that static fixation in depth is much more stable in normal monkeys than in those with strabismus induced in infancy (Upadhyaya et al. 2017a). A third goal of the present study was to determine whether these previously reported fluctuations in horizontal strabismus angle are associated with modulation of SOA activity (hypothesis 3).

METHODS

Subjects and surgical procedures.

Four juvenile rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) served as subjects. All had experimentally induced strabismus. Monkey ET1 was fitted with prism goggles (left eye, 20° base-down; right eye, 20° base-in) for the 1st 3 mo of life. This resulted in a chronic esotropia (typically ~15° but ranging from 0 to 25°). Monkey XT1 underwent a bilateral medial rectus tenotomy the 1st wk of life, which resulted in a strong A-pattern exotropia (35–40° when fixating with the left eye and ~25° when fixating with the right eye). Monkeys ET2 and XT2 received injections of botulinum toxin in the lateral rectus muscle during the 1st 2 wk of life. Three to five follow-up injections were performed between the ages of 4 mo and 2 yr. For monkey ET2, this procedure resulted in a chronic esotropia with a strong A pattern (horizontal strabismus angle was typically 10–20°). Monkey XT2 developed a chronic, highly variable exotropia (horizontal strabismus angle ranged from 0 to 30°). We do not know why the same treatment led to esotropia in one animal and exotropia in the other. Interestingly, however, both animals had a clear esotropia at 4 mo of age. By the time we obtained monkey XT2 (>2.5 yr of age), however, the animal was clearly exotropic (horizontal strabismus angle varied between 0 and 30°) before we implanted eye coils, head post, or chambers. Both of these animals were 5 yr old at the time that experiments began, which means that >3 yr had passed since the last injection of botulinum toxin.

Following the above procedures in infancy, the animals were allowed to mature (>3 yr) before any additional procedures were performed. To prepare the animals for neurophysiological experiments, additional surgeries were performed on each monkey in a dedicated surgical suite. All procedures were in compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Washington National Primate Research Center. To allow the head to be restrained during experiments, a titanium head post (Crist Instrument, Hagerstown, MD) was surgically affixed to the skull with titanium bolts. For monkeys ET1, ET2, and XT1, eye position was measured with high spatial and temporal resolution using the magnetic search coil technique (Fuchs and Robinson 1966; Judge et al. 1980). This required the implantation of scleral search coils underneath the conjunctiva of both eyes. We also used infrared video eye tracking in cases of search coil failure. We used an EyeLink 1000 video eye tracker (SR Research, Kanata, Ontario, Canada) to measure the position of the right eye for the majority of the neurons recorded from one exotropic animal. For six neurons, recorded from monkey XT2, a SensoMotoric Instruments video eye tracker (Teltow, Germany) was used to record the positions of both eyes.

After the animals were trained to perform our behavioral tasks (see below), a recording chamber was implanted over a 16-mm craniotomy, positioned so that the caudal half of oculomotor nucleus could be reached with tracks near the center of the chamber.

Behavioral tasks and visual display.

During recording sessions, the animals sat in a primate chair, positioned at the center of a 1.5-m coil frame (C-N-C Engineering, Seattle, WA), 57 cm from a tangent screen. A 0.25° red laser spot, back-projected onto the screen, served as a visual target. Animals were rewarded every 300 ms with a small amount of applesauce for maintaining fixation of the target within an imaginary 5° reward window. The target remained at a given location for 1.5–5 s, after which it stepped to a different, randomly selected location. The possible target locations were 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 18, and 20° right or left and 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 15° up or down. This permitted us to elicit saccades of >25° in amplitude because the target could step directly between any of these locations. For a normal monkey, the change in vergence angle between the center and most peripheral locations would be quite small (e.g., <1°). However, because strabismic monkeys make horizontally disconjugate saccades, this task elicits easily detectable changes in horizontal strabismus angle, which is mathematically equivalent to a change in vergence angle. Eye position signals were calibrated separately for each eye while that eye was fixating a visual target that stepped from −20 to 20° horizontally and vertically (Walton et al. 2014).

Unit recording and localization of SOA.

We used tungsten in glass microelectrodes (Frederick Haer, Brunswick, ME) to record extracellular activity from individual neurons in SOA. Preliminary detection of spikes was performed online, using a simple threshold criterion. In our data acquisition system (CED Power 1401; Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, United Kingdom), the timing of each spike was then coded as an event mark. Localization of SOA was based on characteristic unit activity, including a tonic firing rate that modulated in association with changes in static horizontal strabismus angle (Das 2011, 2012) and on the basis of proximity to oculomotor nucleus (Mays 1984).

Data analysis.

To verify unit isolation and perform preliminary analyses, data were first visualized offline using Spike2 (Cambridge Electronic Design). Data were then imported into MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) for further analysis. Eye and target position signals were digitized at 1 kHz with 16-bit precision. Eye velocity was computed using three-point differentiation.

Saccade onsets and offsets were detected separately for each eye using a custom algorithm based on a combination of velocity and acceleration criteria, as described in our previous studies (Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2014).

Vergence velocity was defined as:

| (1) |

where V̇HL and V̇HR represent the horizontal velocities of the left and right eyes, respectively. Vergence onsets and offsets were detected using a sliding window algorithm similar to one that has been previously used to detect head movements (Chen and Walton 2005). A vergence onset was detected if all of the following conditions were met: 1) instantaneous vergence velocity exceeded 3°/s for at least 150 ms and 2) vergence velocity exceeded 3°/s at the first time point in the window and the peak vergence velocity exceeded 8°/s. An offset was detected if vergence velocity fell below 3°/s. The advantage of this approach is that the algorithm permits slow movements to be detected using low velocity thresholds without false positives that would otherwise result from noise or small, transient fluctuations in horizontal strabismus angle.

For each isolated neuron, the first step was to determine whether the tonic firing rate was related to static horizontal strabismus angle. To do this, we identified periods of steady fixation, defined as a period of ≥350 ms during which the vectorial velocity of both eyes never exceeded a threshold of 20°/s. In addition, vergence velocity could not exceed 5°/s. MATLAB curve fit tool was then used to perform least-squares linear fits to predict mean firing rate based on horizontal strabismus angle. If the resulting 95% confidence bound for the slope did not include 0, the cell was considered to have a statistically significant sensitivity to horizontal strabismus angle. We then compared the rate-position curve slopes with those obtained from normal animals in a previously published study (Pallus et al. 2018).

A given neuron was included in subsequent analyses if all of the following criteria were met: 1) a linear fit to the relationship between static horizontal strabismus angle (during periods of steady fixation) and mean firing rate yielded a slope that was significantly different from 0 and/or firing rate was significantly correlated with vergence velocity (see below) and 2) the rate-position curves for horizontal left eye position, horizontal right eye position, vertical left eye position, and vertical right eye position yielded lower r2 values than the one for horizontal strabismus angle.

Saccades were divided into the following four categories, based on which eye was fixating the target at the time of the target step and which eye was on target after the movement ended: “left eye viewing,” “right eye viewing,” “left-right fixation switching,” and “right-left fixation switching.”

Four different temporal Epochs were defined: 1) the Presaccadic Fixation Epoch was 100 ms in duration and began 300 ms before the onset of each saccade; 2) the Intrasaccadic Epoch began with saccade onset and ended with saccade offset; 3) the Postsaccadic Epoch began at saccade offset and was 100 ms in duration; and 4) the Postsaccade Fixation epoch was defined as the period from 300 to 400 ms after saccade offset. Neural activity associated with these epochs was time-shifted by 20 ms to compensate for neural processing delays (Pallus et al. 2018). These four epochs were analyzed separately for saccades with on-direction and off-direction horizontal disconjugacy. For a far-response cell, “on-direction disconjugacy” would be a divergent saccade: an increase in the angle of exotropia or a decrease in the angle of esotropia. A one-way ANOVA was used to test the null hypothesis that there were no differences in mean firing rate for any of these eight conditions. Correction for multiple pairwise comparisons was performed using the Tukey-Kramer test. Fixation-switching saccades were excluded from this analysis.

In normal monkeys, some SOA neurons with vergence velocity sensitivity display burst-tonic properties, such that the firing rates during vergence movements exceed the levels expected based on vergence position alone (Mays et al. 1986; Pallus et al. 2018). If SOA neurons carry vergence velocity signals during disconjugate saccades in strabismus, the mean firing rate should be higher during the Intrasaccadic Epoch than in the Postsaccade Fixation epoch when the disconjugacy is in the on direction of the neuron. For a convergence neuron, the adjusted firing rate (FRvel, from Eq. 3, see below) should be positive for saccades that increase esotropia or decrease exotropia (V̇V would be positive in either case). For a divergence neuron, FRvel should be positive when V̇V is negative during a saccade.

To determine whether the tonic firing rates of SOA neurons encode changes in horizontal strabismus angle associated with disconjugate saccades, we also computed a tonic modulation index (TMI) using:

| (2) |

where and represent the mean firing rates during the Postsaccadic Fixation and Presaccadic Fixation Epochs, respectively. A TMI value of 0 would indicate no modulation at all, positive values indicate higher tonic firing rates after the saccade, and negative values would indicate that the tonic firing rate decreased after the saccade.

To determine whether some SOA neurons, in strabismus, show bursts similar to those that are thought to encode vergence velocity in normal primates, we computed a “burst index” using:

| (3) |

where represents the mean firing rate during the saccade. A positive value of BI would indicate that the firing rate was higher during the Intrasaccadic Epoch than the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch. A negative value would indicate that the firing rate was lower during the Intrasaccadic Epoch compared with the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch. Thus BI detects enhancements or decrements in firing rate in a way that is unaffected by the accuracy of estimates of the sensitivity of the neuron to static horizontal strabismus angle.

First-order models with position and velocity terms have been shown to provide a good description of other types of neurons that show burst-tonic firing patterns, such as motoneurons (Robinson 1970; Sylvestre and Cullen 1999, 2002; Van Horn and Cullen 2009). However, for monkeys with pattern strabismus, models that only include terms for vergence position and velocity might not be able to predict the firing rates of burst-tonic neurons in SOA successfully. This is because SOA neurons do not encode changes in horizontal strabismus angle associated with changes in vertical eye position (Das 2012). We were concerned that, in a monkey with pattern strabismus, attempts to fit SOA data with this type of model might result in a poor fit, with large residuals correlated with vertical eye position. With this in mind, we reasoned that the addition of a term for vertical position might improve the fit:

| (4) |

where I represents the vertical position of the eye ipsilateral to the recording site. The term kvertI(t + td) effectively adjusts the predicted firing rate to compensate for the relationship between vertical eye position and horizontal strabismus angle. The expression (t + td) is a time shift to compensate for neural processing delays. As we have recently done for model fits of SOA neurons in normal monkeys (Pallus et al. 2018), we used a value of 20 ms for all neurons. A given saccade was included in these dynamic analyses only if the same eye was on target before and after the saccade. A given neuron was included only if >10 saccades were found for each of the 2 viewing eye conditions.

Hypothesis 3 concerned the question of whether slow fluctuations in horizontal strabismus angle are associated with modulation of SOA activity. For this analysis, our algorithm searched for movements that lasted ≥150 ms, with a peak vergence velocity of ≥8°/s (either convergence or divergence) and no detectable saccades (hereafter referred to as “vergence-only” movements). Equation 4 was used to analyze the relationship between firing rate and vergence-only movements. The analysis was only performed on a given neuron if >10 vergence-only movements were detected.

For all dynamic analyses, bootstrap confidence intervals were computed by randomly selecting, with replacement, n movements (saccades or vergence-only movements), where n was equal to the number of relevant movements detected. This process was then repeated 1,999 times. Next, 95% confidence intervals were estimated using the “bias-corrected accelerated” method (Chernick and LaBudde 2011; Davison and Hinkley 1997). A given parameter was considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval did not include 0. Hypothesis 2a predicts that, in the absence of a fixation switch, the velocity term should be 0; hypothesis 2b predicts that it should be significantly different from 0.

In our recent study of SOA activity during disjunctive saccades in normal primates, we modified the dynamic equation to predict vergence velocity (Pallus et al. 2018). This was done to test the hypothesis that the high vergence velocities during saccades result from mechanisms that do not involve SOA. A similar analysis was performed in the present study, for a similar reason. If horizontal saccade disconjugacy in strabismus is due primarily to contextually inappropriate modulation of activity in SOA, then one should be able to use the firing rate to generate a reasonable prediction of vergence velocity. With this in mind, the data were also fit with:

| (5) |

where P is vertical eye position. The variables b, c, kverg, and kvert are constants. Equation 5 was first used on vergence-only movements; we then asked whether the resulting parameter estimates were able to predict vergence velocity during saccades accurately.

RESULTS

Sixty-two neurons met our inclusion criteria (see methods), including twenty-eight from the two esotropes and thirty-four from the two exotropes. Of these, there were forty-four near-response cells (those that displayed increased firing rates for increased esotropia or decreased exotropia) and eighteen far-response cells (increased firing rates for decreased esotropia or increased exotropia). The proportions of near-response neurons for our four monkeys were as follows: ET1 = 67%; ET2 = 71%; XT1 = 71%; XT2 = 83%. Neurons that failed to show a significant sensitivity to either horizontal strabismus angle or the first derivative of horizontal strabismus angle (mathematically equivalent to vergence velocity) were not analyzed further, even if they were believed to be in SOA. Five neurons were rejected for this reason, including three from monkey ET2 and two from monkey XT1. This might have caused us to underestimate the abnormalities of near-response cells if the rejected neurons retain the normal functional connectivity for SOA, but this was deemed preferable to running the risk of overestimating the size of the effects.

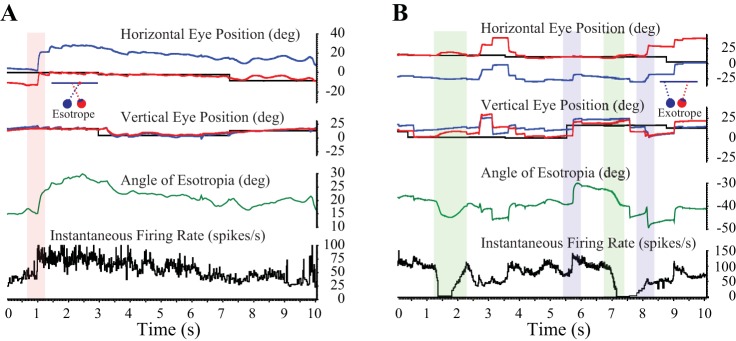

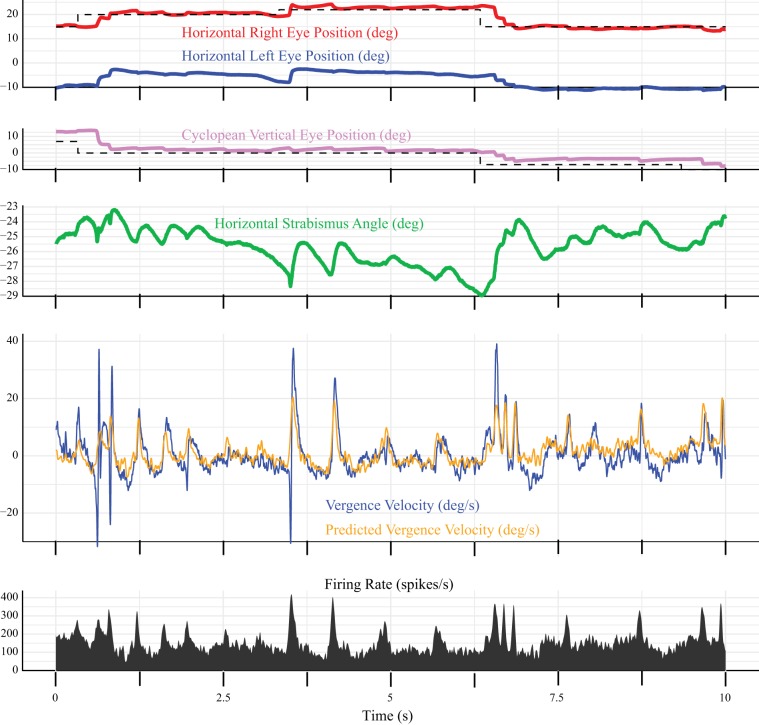

Figure 1 shows example raw data from monkeys ET2 (A) and XT1 (B), showing many of the movements that were of interest in this study. In Fig. 1A, the red rectangle highlights a left-right fixation-switching saccade that is associated with a rapid increase in the angle of esotropia and a coincident increase in the firing rate of the neuron. Over the next 7–8 s, there is a gradual decrease in the angle of esotropia in the absence of additional fixation switches. Note that the tonic firing rate of the neuron over this period gradually declines, from a high near 80 spikes/s to a low near 40 spikes/s. In Fig. 1B, the green rectangles highlight momentary increases in the angle of exotropia in the absence of any detectable saccades. In both cases, the neuron ceases discharge shortly before this occurs. The blue rectangles highlight two horizontally disconjugate saccades. The first is upward, with the right eye viewing, and is associated with a decrease in the angle of exotropia and an increase in the tonic firing rate. The second blue rectangle shows a saccade in which the monkey briefly looks away from the target. The change in horizontal strabismus angle is in the off direction of the neuron (based on the sensitivity of the neuron to static horizontal strabismus angle), yet the firing rate increases. These examples indicate that SOA neurons of strabismic animals sometimes modulate during the performance of a saccade task on a tangent screen, even in the absence of a fixation switch. However, these firing rate changes do not consistently relate to observed changes in horizontal strabismus angle.

Fig. 1.

Raw data showing examples of many of the movements analyzed in this study. A: monkey ET2. B: monkey XT1. Magenta rectangle: left-right fixation-switching saccade. There is little or no vergence velocity response, but the tonic firing rate increases in association with the increase in the angle of esotropia. Purple rectangles: changes in the tonic firing rate were sometimes observed in the absence of a fixation switch, but they were not consistently predictive of the direction of the horizontal disconjugacy. In the present examples, note that clear increases in tonic firing rate were observed after one saccade that decreased the exotropia and one that increased it. Green rectangles: “vergence-only” movements were slow changes in horizontal strabismus angle, made in the absence of any detectable saccades. These movements were often associated with clear changes in firing rate. deg, Degrees.

Tonic firing rate.

As a first step, we compared the horizontal strabismus angle sensitivities of our esotropic and exotropic subjects to vergence rate-position curve slopes obtained from normal monkeys reported previously (Pallus et al. 2018; hypothesis 1). Figure 2 shows example rate-position curves from 3 neurons. Figure 2A shows one of the most convincing examples, a neuron recorded from monkey ET2 that showed a particularly robust rate-position curve (r2 value was the 3rd highest in our data set). Figure 2B shows a typical example (r2 value very close to the mean for our entire data set), recorded from monkey XT2, and Fig. 2C shows the worst example (based on r2 value; see Table 1) that was still included in our data set as “strabismus angle related” (recorded from monkey ET2).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between static horizontal strabismus angle and mean tonic firing rate for 3 example neurons in the supraoculomotor area. A shows one of the most convincing examples. B shows a more typical example. C shows the weakest (based on r2 value) relationship of any neuron that was included in subsequent analyses. For this analysis, data from right eye viewing and left eye viewing were pooled. deg, Degrees.

Table 1.

Results of linear regression analysis of the relationship between horizontal strabismus angle and tonic firing rate during periods of steady fixation

| Cell | Y-Intercept | Slope | r2 | Cell Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET1_1 | 50.6 | 4.63 | 0.58 | Near |

| ET1_2 | 68.7 | 6.43 | 0.02 | Far* |

| ET1_3 | 25.1 | −5.95 | 0.14 | Far |

| ET1_4 | 29.6 | 2.85 | 0.21 | Near |

| ET1_5 | 36.8 | 2.92 | 0.08 | Near |

| ET1_6 | 18.5 | −1.23 | 0.14 | Far |

| ET1_7 | 67.9 | 1.86 | 0.07 | Near |

| XT1_8 | 158 | 2.33 | 0.74 | Near |

| XT1_9 | 51.5 | 0.77 | 0.01 | Near |

| XT1_10 | 256.9 | 4.25 | 0.14 | Near |

| XT1_11 | 49.6 | 0.98 | 0.51 | Near |

| XT1_12 | 198.3 | 2.49 | 0.09 | Near |

| XT1_13 | 370.5 | 7.22 | 0.33 | Near |

| XT1_14 | 66.5 | −1.91 | 0.04 | Far |

| XT1_15 | 26.7 | −1.75 | 0.07 | Far |

| XT1_16 | 301.4 | 5.35 | 0.09 | Near |

| XT1_17 | 12.1 | −0.94 | 0.08 | Far |

| XT1_18 | 351.5 | 7.67 | 0.71 | Near |

| XT1_19 | 141.6 | 3.18 | 0.46 | Near |

| XT1_20 | 86.0 | 1.45 | 0.12 | Near |

| XT1_21 | 105.3 | 1.86 | 0.27 | Near |

| XT1_22 | 72.7 | 0.24 | 0.01 | Near |

| XT1_23 | 104.9 | 0.51 | 0.01 | Near |

| XT1_24 | 106.4 | 1.20 | 0.14 | Near |

| XT1_25 | 85.2 | −0.67 | 0.02 | Far |

| XT1_26 | 217.8 | 3.47 | 0.47 | Near |

| XT1_27 | 8.4 | −1.68 | 0.12 | Far |

| XT1_28 | 180.1 | 2.86 | 0.05 | Near |

| XT1_29 | 26.3 | −0.62 | 0.02 | Far |

| XT1_30 | −8.7 | −0.91 | 0.13 | Far |

| XT1_31 | −9.9 | −0.71 | 0.20 | Far |

| XT1_32 | 165.7 | 2.96 | 0.47 | Near |

| XT1_33 | 157.2 | 1.85 | 0.12 | Near |

| XT1_34 | −59.1 | −2.30 | 0.40 | Far |

| XT1_35 | 77.0 | 0.97 | 0.02 | Near |

| XT2_36 | 96.9 | 2.97 | 0.05 | Near |

| XT2_37 | 169.4 | 6.24 | 0.23 | Near |

| XT2_38 | 255.6 | −8.0 | 0.05 | Far |

| XT2_39 | 83.3 | 2.43 | 0.18 | Near |

| XT2_40 | 166 | 7.50 | 0.17 | Near |

| XT2_41 | 85.9 | 1.96 | 0.06 | Near |

| ET2_42 | 36.3 | 1.88 | 0.34 | Near |

| ET2_43 | 70.1 | −1.16 | 0.06 | Far |

| ET2_44 | 16.9 | 0.48 | 0.06 | Near |

| ET2_45 | 28.2 | 1.16 | 0.13 | Near |

| ET2_46 | 14.6 | 3.22 | 0.12 | Near |

| ET2_47 | −1.0 | 3.66 | 0.19 | Near |

| ET2_48 | −14.5 | 4.63 | 0.35 | Near |

| ET2_49 | 29.3 | 2.62 | 0.13 | Near |

| ET2_50 | −9.3 | 4.87 | 0.60 | Near |

| ET2_51 | 66.3 | 3.85 | 0.29 | Near |

| ET2_52 | 152.9 | −0.98 | 0.01 | Far |

| ET2_53 | 44.7 | 0.20 | 0.01 | Near |

| ET2_54 | 47.4 | −2.87 | 0.11 | Far |

| ET2_55 | 10.9 | 1.15 | 0.24 | Near |

| ET2_56 | 79.2 | −0.24 | 0.02 | Far |

| ET2_57 | 75.1 | −0.47 | 0.01 | Far |

| ET2_58 | 55.7 | 0.19 | 0.02 | Near |

| ET2_59 | 87.2 | −0.73 | 0.04 | Far |

| ET2_60 | 14.3 | 1.43 | 0.25 | Near |

| ET2_61 | −17.0 | 4.77 | 0.37 | Near |

| ET2_62 | 50.5 | 0.41 | 0.01 | Near |

Neuron was unusual; it was classified as a far-response cell, despite the positive slope, because it consistently showed robust increases in firing rate during movements that decreased the esotropia (mathematically equivalent to divergence velocity).

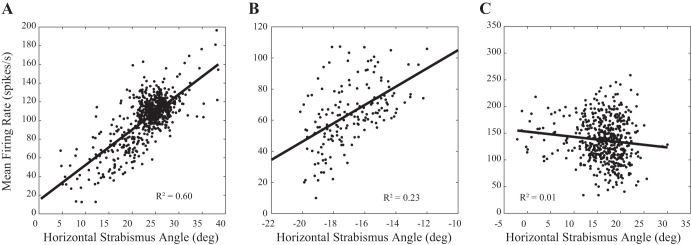

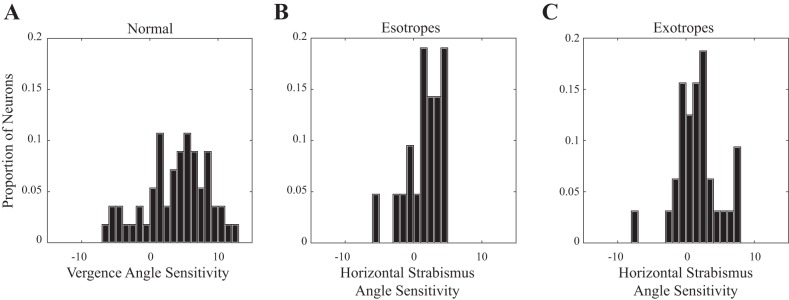

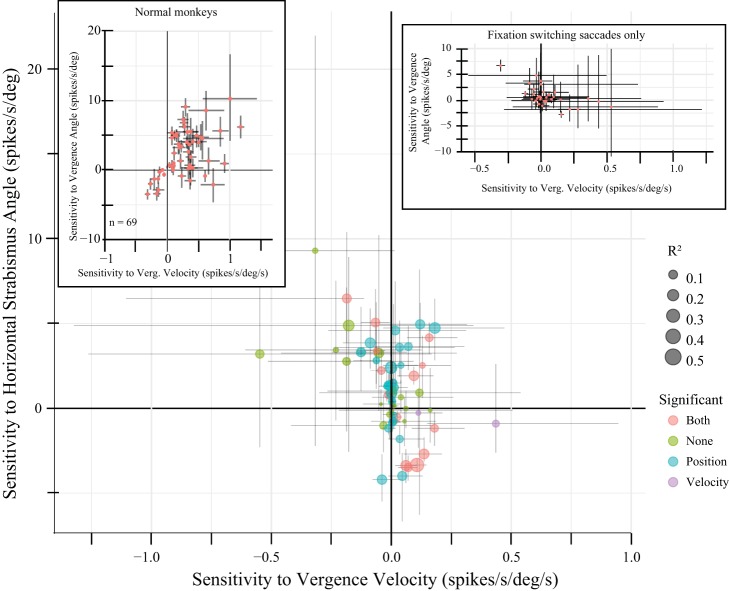

Figure 3 shows the distributions of slopes for normal monkeys (A), esotropes (B), and exotropes (C). In all three groups, there were some neurons with very small slopes. In both esotropic and exotropic subjects, however, there were few neurons with slopes >5. The mean slopes for near-response cells were 2.39 (esotropes), 2.71 (exotropes), and 5.75 (normal). Slopes were significantly lower for both esotropes and exotropes compared with the normal monkeys (2-tailed t-tests, P < 0.01 for both comparisons). There was no significant difference between esotropes and exotropes (P = 0.93). The mean y-intercepts for near-response cells were 29.0 (esotropes), 19.5 (normal), and 156.4 (exotropes). There was no significant difference in the mean y-intercept between the esotropes and normal monkeys (2-tailed t-test, P = 0.19), but a significant difference was found between exotropes and normal monkeys (2-tailed t-test, P < 0.01). For far-response cells, the mean slopes for esotropes and exotropes were −1.7 and −1.94, respectively. Mean y-intercepts were 69.4 (esotropes) and 40.3 (exotropes). No significant difference was found between esotropes and exotropes for either the slopes (P = 0.81) or the y-intercepts (P = 0.39).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of slopes for horizontal strabismus angle rate-position curves (examples are shown in Fig. 1) across all neurons in our sample. A: for the normal animals, a wide range of slopes was found. Distribution showed a symmetrical peak near 5, but there were some neurons with slopes of ≥10. B: for esotropes, most neurons had slopes between approximately 1 and 4. Near-response cells with slopes >5 were conspicuously absent. C: for the exotropes, there was a clear preponderance of neurons with very small slopes. For the strabismic animals, there were no near-response cells with slopes >7.7.

Although there was no difference, overall, between esotropes and exotropes, the sensitivity to horizontal strabismus angle differed between animals. Because of the small number of recordings from monkeys ET1 (n = 7) and XT2 (n = 6), comparisons between individual animals were performed by pooling near- and far-response cells together and comparing the absolute values. The mean slope was significantly larger for monkey ET1 (prism reared) compared with monkey ET2 (botulinum toxin; ET1 mean = 3.7; ET2 mean = 1.95; 2-tailed t-test, P = 0.03). The mean slope was significantly smaller for monkey XT1 (medial rectus tenotomy) compared with monkey XT2 (botulinum toxin; XT1 mean = 2.25; XT2 mean = 4.85; P < 0.01). The two animals with the largest horizontal strabismus angles (XT1 and ET2) also had the weakest sensitivities to horizontal strabismus angle. No significant differences were found for y-intercept (ET1 vs. ET2, P = 0.88; XT1 vs. XT2, P = 0.59).

These linear fits were better for the near-response cells than for the far-response cells (near-response cells: mean r2 = 0.22, range 0.01–0.74; far-response cells: mean r2 = 0.09, range 0.01–0.40). A two-tailed t-test revealed a significant difference (P = 0.01).

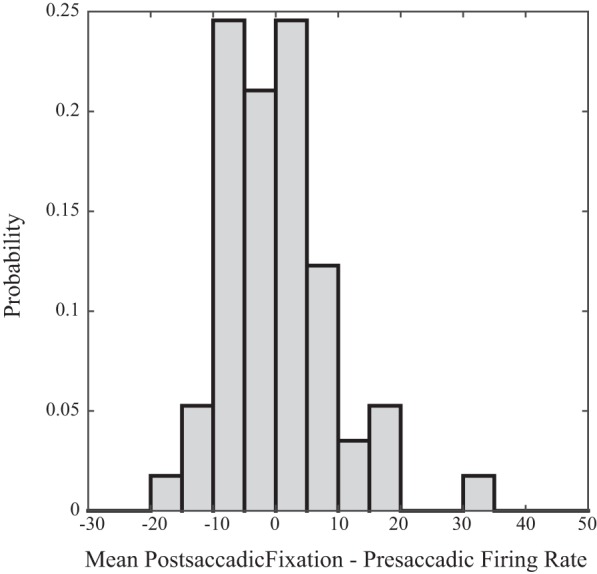

We next sought to determine whether the tonic firing rates of SOA neurons encode changes in horizontal strabismus angle resulting from horizontally disconjugate saccades not associated with a fixation switch (hypothesis 2). If they do, one would expect the mean firing rate to be higher for the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch, compared with the Presaccadic Fixation Epoch, when the change in horizontal strabismus angle is in the on direction of the neuron. Fixation-switching saccades were excluded from this analysis, as were all saccades with off-direction horizontal disconjugacy, no horizontal disconjugacy, or on-direction horizontal disconjugacy <3°. This value was chosen in an effort to strike a balance between ensuring that horizontal disconjugacy was large enough to yield a detectable effect while also ensuring a large enough sample size for statistical analyses. A given neuron was included in this analysis only if ≥6 saccades met these inclusion criteria (n = 57). For a typical neuron, between 20 and 30 saccades met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 4 is a histogram showing, for each neuron, the mean change in tonic firing rate following saccades with on-direction changes in horizontal strabismus angle (postsaccadic fixation minus presaccadic). Overall, 10/57 neurons (17.5%) showed significantly higher firing rates in the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch compared with the Presaccadic Fixation Epoch. For two of these neurons, the mean firing rate in the postsaccadic fixation epoch was higher by >60 spikes/s. Typically, however, the differences were quite small (mean difference, across our sample of neurons, was 5.5 spikes/s) even when there was a significant difference. Interestingly, 4/57 neurons (7%) showed significantly lower tonic firing rates in the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch. Across the entire sample, the mean tonic modulation index was <0.025. This indicates that, in the absence of a fixation switch, there was little or no change in the population tonic firing rate after saccades with on-direction disconjugacy of ≥3°.

Fig. 4.

Histogram showing the distribution of the mean change in tonic firing rate following saccades with ≥3° of horizontal disconjugacy in the on direction of the neuron (postsaccadic epoch minus presaccadic epoch) for our sample of neurons. Fixation-switching saccades were excluded from this analysis.

Contextually inappropriate slow vergence (hypothesis 3).

All four animals displayed occasional, small-amplitude fluctuations in the horizontal strabismus angle during fixation of stationary targets (the green rectangles in Fig. 1 highlight two particularly large examples, both of which were associated with sharp decreases in the firing rate). Across all recordings in our sample, our algorithm detected 5,892 slow convergence and divergence movements with amplitudes of ≥0.5°, in the absence of a detectable saccade (hereafter referred to as vergence-only movements). Note, however, that our algorithm was unable to detect very slow fluctuations in horizontal strabismus angle that occurred over much longer time periods, such as the one shown in Fig. 1A. Although most were small, there were 1,494 with amplitudes >3° and 450 with amplitudes >5°.

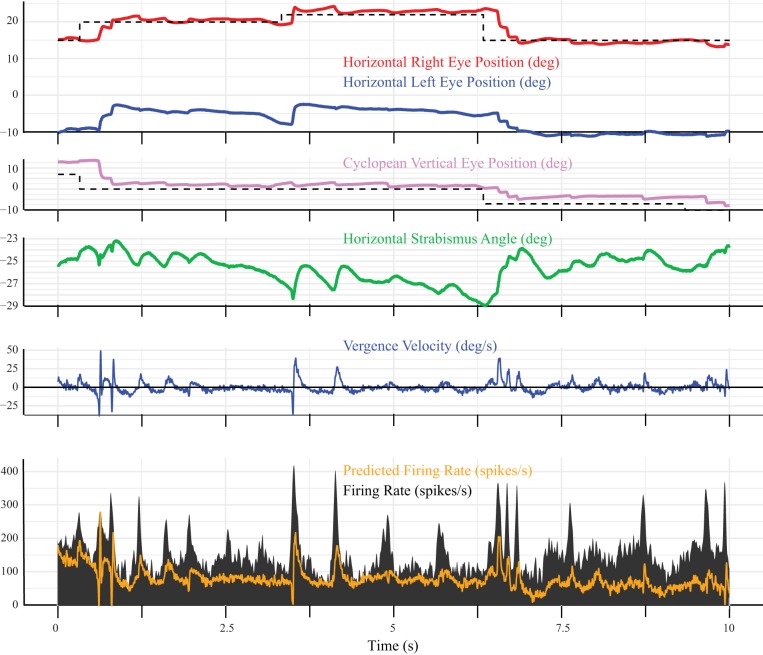

To determine whether these fluctuations in horizontal strabismus angle were associated with modulation of neuronal activity in SOA, a dynamic analysis was performed, using Eqs. 4 and 5. Figure 5 shows an example model fit (Eq. 4) for a neuron with an unusually robust sensitivity to vergence velocity. The static rate position curve analysis showed that the tonic firing rate of this neuron was highly variable for a given horizontal strabismus angle, which explains why the model was often unable to predict the tonic firing rate when the eyes were not moving. In this figure, one can see that periods of convergence (i.e., vergence velocity >0) consistently coincided with bursts of spikes. To emphasize this point, we fit the same data with Eq. 5, which uses the firing rate to predict vergence velocity (Fig. 6). As before, the parameter estimates were based on fits to the vergence-only movements. They were then used to predict the velocity for the entire recording, including during saccades. The fit looks better in Fig. 6, perhaps because the tonic firing rates, when the eyes were not moving, were much lower than the bursts, which means that they did not have a large effect on the predicted velocity. Note, however, that the model consistently underestimated the peak vergence velocity during saccades. Although this neuron turned out to be atypical, this gave us confidence that our mathematical modeling approach could successfully identify neurons with strong vergence velocity sensitivity.

Fig. 5.

Example dynamic model fit for a neuron (recorded from monkey XT1) that showed an unusually strong vergence velocity sensitivity. Note that the animal fixates the target with the right eye (shown in red) throughout this 10-s segment of data. Horizontal strabismus angle (green) fluctuates constantly, even in the absence of a saccade. Pink, vertical eye position; blue, vergence velocity; black, firing rate; orange, firing rate predicted by the model (Eq. 4). The model often failed to predict the tonic firing rate during periods of steady fixation but did predict the bursts of spikes that were consistently associated with convergence (i.e., vergence velocity >0). Model parameters were estimated using vergence-only movements and then used to generate a predicted firing rate for the entire recording. deg, Degrees.

Fig. 6.

Same segment of data shown in Fig. 5, but this time the data were fit with Eq. 5, which generates a predicted vergence velocity (orange trace) based on the firing rate of the neuron. All other conventions are the same as in Fig. 5. deg, Degrees.

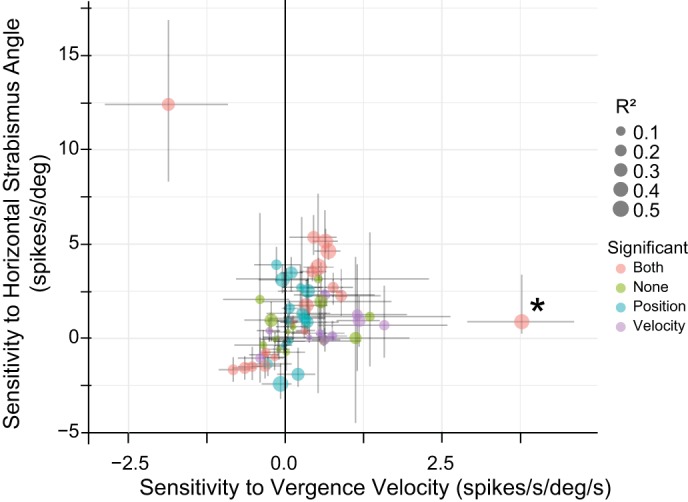

When the data were fit with Eq. 4, four neurons were excluded because <10 vergence-only movements were detected. Of the remaining 58 neurons, the horizontal strabismus angle (position) term was significant for 34 (59%) and the vergence velocity term was significant for 29 (50%). Figure 7 compares these 2 parameter estimates for all 58 neurons. The atypical neuron shown in Figs. 5 and 6 is indicated by an asterisk. In the top-left corner of Fig. 7, one can see a neuron with a significant negative sensitivity to vergence velocity and a significant positive sensitivity to horizontal strabismus angle. This neuron, recorded from monkey ET1, reliably showed a burst of spikes during decreases in the angle of esotropia but rarely showed any tonic discharge. We speculate that the apparent sensitivity to horizontal strabismus angle occurred because this neuron occasionally requested decreases in the angle of esotropia that either did not occur or were too slow to be detectable.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of estimated sensitivities (using Eq. 4) with horizontal strabismus angle (mathematically equivalent to vergence angle) and vergence velocity for vergence-only movements (i.e., those without accompanying saccades; examples of such movements can be seen in Fig. 1, highlighted in green). The neuron used in Figs. 5 and 6 is indicated with an asterisk. The size of the dot indicates the r2 value, and the color indicates which terms were significant (orange, both; green, neither; blue, horizontal strabismus angle only; purple, vergence velocity only). The vergence velocity term was significant for 50% of the neurons. The outlier in the top-left corner was a divergence velocity neuron that rarely showed any tonic discharge. Crosses represent bootstrap confidence intervals (see methods). deg, Degrees.

Some neurons in Fig. 7 showed a clear sensitivity to horizontal strabismus angle but no velocity sensitivity (data points near the solid vertical line). Other neurons were clearly more sensitive to vergence velocity than horizontal strabismus angle. One of the most convincing examples of the latter is the neuron shown in Figs. 5 and 6, marked with an asterisk in Fig. 7. Despite the well-known impairment of disparity vergence in strabismus, it is clear that a subset of SOA neurons is sensitive to vergence velocity in monkeys with experimentally induced strabismus. It is also clear that contextually inappropriate fluctuations in horizontal strabismus angle, which occurred in the absence of saccades, were associated with changes in SOA firing rates.

Vergence velocity effects during saccades (hypothesis 2).

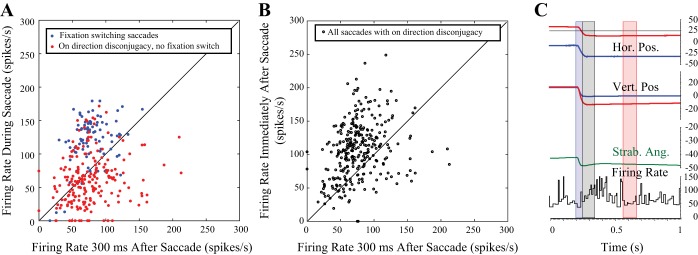

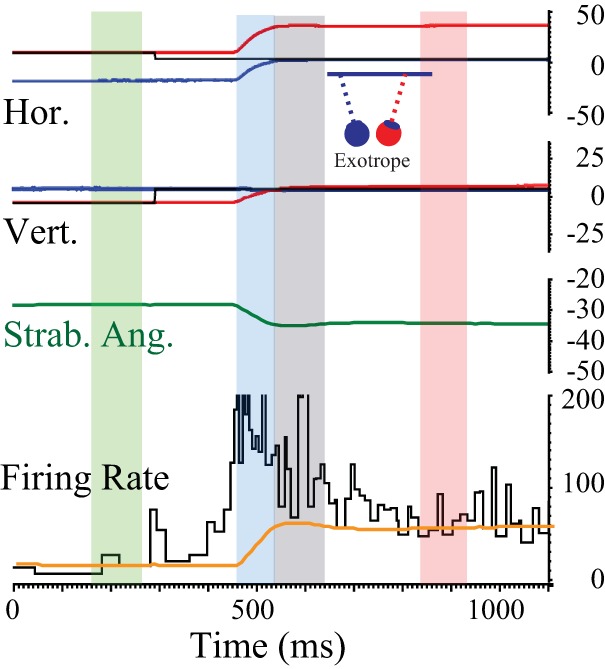

In normal monkeys, some SOA neurons carry vergence velocity signals during disjunctive saccades made between targets that differ in both direction and distance, but they do not fully encode the high vergence velocities characteristic of these movements (Pallus et al. 2018). We wondered whether SOA neurons in strabismic monkeys behave in a similar manner during horizontally disconjugate saccades between targets on a tangent screen. Figure 8 shows an example fixation-switching saccade from monkey XT1 that illustrates the four epochs. As has been reported previously (Das 2012), the tonic firing rate clearly modulates in association with the change in horizontal strabismus angle coincident with the fixation switch. The firing rate during the Intrasaccadic Epoch (blue) is much higher than during the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch (red). Figure 9 compares the mean firing rates during the Intrasaccadic (red/blue) and Postsaccadic (black) epochs to the mean firing rates in the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch for one example neuron, recorded from monkey XT1. Each data point represents a single saccade associated with an on-direction change in horizontal strabismus angle. This near-response cell typically exhibited a burst of spikes during left-right fixation-switching saccades (blue), which were consistently associated with a decrease in the angle of exotropia. Thus these data points usually fall above the unity line. When the monkey made saccades with on-direction horizontal disconjugacy in the absence of a fixation switch (red), the firing rate during the Intrasaccadic Epoch could be either higher or lower than during the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch but was more often lower. Thus the red data points fall below the unity line more often than above it. Immediately after these same saccades (Postsaccadic Epoch, black points), the firing rate was usually higher than during the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch. Note, however, that there were also exceptions to each of the general tendencies mentioned above; there were a few saccades with clear bursts in the absence of a fixation switch, a few left-right fixation-switching saccades without bursts, and examples of lower firing rates in the Postsaccadic Epoch than the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch. When all saccades with on-direction disconjugacy (but no fixation switch) were analyzed for this neuron, the mean firing rate was significantly lower for the Intrasaccadic Epoch compared with the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch (2-tailed t-test). The same was true for 20/62 neurons, even though the change in horizontal strabismus angle was in the on direction. Four cells showed significantly higher firing rates for the Intrasaccadic Epoch compared with the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch.

Fig. 8.

Perisaccadic data were divided into 4 temporal epochs. The example movement is a right-left fixation-switching saccade. 1) The Presaccadic Fixation Epoch (highlighted with a green rectangle) was 100 ms in duration and began 300 ms before the onset of each saccade. 2) The Intrasaccadic Epoch (blue rectangle) began with saccade onset and ended with saccade offset. 3) The Postsaccadic Epoch (gray rectangle) began at saccade offset and ended 100 ms later. 4) The Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch (magenta rectangle) covered the period from 300 to 400 ms after saccade offset. Horizontal strabismus angle (Strab. Ang.; mathematically equivalent to vergence angle) is shown in dark green. Orange trace shows the firing rate that would be expected based solely on the current horizontal strabismus angle (derived from the linear fits to the static rate-position curves). Instantaneous firing rates in excess of this value are assumed to be related to vergence velocity. Hor., horizontal eye position; Vert., vertical eye position.

Fig. 9.

Mean firing rates in different epochs for one example neuron. A: each data point represents a single comparison for an individual saccade. Red: comparison of mean firing rate during the Intrasaccadic and Postsaccadic Fixation Epochs for saccades with on-direction horizontal disconjugacy, made in the absence of a fixation switch. Note that the firing rates during these saccades were highly variable and were often lower than they were 300–400 ms later. Blue: comparison of mean firing rate during the Intrasaccadic and Postsaccadic Fixation Epochs for fixation-switching saccades with on-direction horizontal disconjugacy. For this animal, left-right fixation-switching saccades were consistently associated with decreased exotropia; for this neuron, these movements were usually accompanied by a small, but clear, burst of spikes that exceeded the firing rate 300–400 ms later. B, black open circles: comparison of mean firing rate during the Postsaccadic Epoch and Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch for saccades with on-direction horizontal disconjugacy made in the absence of a fixation switch. C: example saccade in which the firing rate transiently increases after the end of the saccade. Hor. Pos., horizontal eye position; Strab. Ang., horizontal strabismus angle; Vert. Pos., vertical eye position.

One might wonder whether the lower firing rates for the Intrasaccadic Epoch, compared with the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch, might indicate a delayed increase in the tonic firing rate, as opposed to a genuine decrement during the movement. To address this issue, we compared the mean firing rates during the Presaccadic and Intrasaccadic Epochs for saccades with on-direction horizontal disconjugacy in the absence of a fixation switch. The mean firing rate was significantly lower for the Intrasaccadic Epoch, compared with the Presaccadic Epoch, for 21/62 neurons. Furthermore, for 14/62 neurons, the mean firing rate was significantly lower during the Intrasaccadic Epoch than both the Presaccadic and Postsaccadic Fixation Epochs. Thus, for some of the neurons in our sample, the firing rate showed a genuine decrease during saccades that changed the horizontal strabismus angle in what should have been the on direction. There were four neurons for which the mean firing rate was significantly higher for the Intrasaccadic Epoch compared with either the Presaccadic or Postsaccadic Fixation Epochs.

The unexpected finding of a reduction in firing rate for saccades with on-direction changes in horizontal strabismus angle led us to wonder if the slow vergence system might be attempting to compensate for horizontal saccade disconjugacy. If so, we reasoned, perhaps there would be an analogous compensatory response (i.e., an increase in firing rate) when the saccade disconjugacy was in the off-direction of the neuron. Restricting the data set to include only saccades with off-direction horizontal disconjugacy revealed that the mean firing rate was significantly lower during the Intrasaccadic Epoch, compared with the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch, for 22/62 neurons. Five neurons showed significantly higher firing rates for the Intrasaccadic Epoch compared with the Postsaccadic Fixation Epoch.

Next, we compared the mean burst indexes for saccades with on-direction vs. off-direction horizontal disconjugacy. Mean burst indexes were significantly higher for the on direction for 6/62 neurons and were significantly higher for the off direction for 3/62 neurons. Across our sample of neurons, the mean burst index for saccades with on-direction disconjugacy was −0.1086. For saccades with off-direction disconjugacy, the mean burst index was −0.1182.

The above analyses involved pooling saccades with on or off direction changes in horizontal strabismus angle, regardless of the amplitude or peak vergence velocity. Modulation of SOA neuron activity during the Intrasaccadic Epoch might still exert a small (but detectable) influence. As noted above, pattern strabismus might complicate efforts to model the firing rates of SOA neurons mathematically since they do not encode changes in horizontal strabismus angle associated with changes in vertical eye position (Das 2012). We (Walton and Mustari 2017) have recently shown that, in monkeys with pattern strabismus, horizontal saccade disconjugacy is correlated with the amplitude of the vertical component. (Monkeys ET1, ET2, and XT2 are the same animals as the ones used in this previous study.) It is possible that poor correlations between firing rates and horizontal strabismus angle might be solely the result of a failure to take this into account. With these issues in mind, the data during saccades were fit with dynamic Eq. 4, which includes a term related to cyclopean (i.e., average of left and right eye) vertical eye position. As before, fixation-switching saccades were excluded from this dynamic analysis.

The dynamic model fits were performed on 62 neurons, for the Intrasaccadic Epoch, for saccades made in the absence of a fixation switch. Figure 10 shows the resulting position and velocity parameter estimates for all neurons. The horizontal strabismus angle term was significantly different from 0 for 39/62 neurons (63%), whereas the vergence velocity term was significantly different from 0 for 17/62 cells (27%). However, it should be noted that the velocity sensitivities were between −0.5 and 0.5 for all neurons. Only one neuron showed a statistically significant velocity sensitivity >0.25. From the tight clustering of points around 0 on the x-axis, it is clear that very few neurons showed a robust sensitivity to vergence velocity during saccades. The mean absolute value of the velocity sensitivity, measured during saccades, was significantly higher for esotropes (0.13) compared with exotropes (0.04; t-test, P < 0.001).

Fig. 10.

Comparison of horizontal strabismus angle and vergence (Verg.) velocity sensitivities during saccades made in the absence of a fixation switch. Crosses represent bootstrap confidence intervals (see methods). All conventions are the same as in Fig. 6. Of 60 neurons, the horizontal strabismus angle sensitivity was significantly different from 0 for 39 (65%), whereas the vergence velocity term was significantly different from 0 for 17 cells (28%). Note, however, that the velocity sensitivities were mostly clustered around 0; only 1 neuron showed a statistically significant velocity sensitivity >0.25. This is quite different from the more robust velocity sensitivities observed during vergence-only movements (Fig. 7). Left inset shows the results of performing the same analysis on near-response cells collected from normal monkeys performing a saccade-vergence task for a previously published study (Pallus et al. 2018). Note that the velocity responses were much weaker in monkeys with strabismus, performing a saccade task on a tangent screen. Inset on the right shows the results of this same analysis for fixation-switching saccades. deg, Degrees.

Hypothesis 2 (see introduction) concerned the issue of whether horizontal saccade disconjugacy in strabismus was associated with a contextually inappropriate (i.e., when targets are presented on a tangent screen) modulation of SOA neuron activity. The above analyses indicate that velocity sensitivities are weak in the absence of a fixation switch. To consider this issue more thoroughly, we compared the above velocity sensitivities with those obtained from SOA neurons in normal monkeys performing a saccade-vergence task for a previously published study (Pallus et al. 2018). The mean absolute value of velocity terms was significantly higher in normal monkeys (0.33) performing a saccade-vergence task (Fig. 10, inset in top-left corner), compared with those obtained from strabismic monkeys performing a saccade task on a tangent screen for the present study (0.08; t-test, P < 0.0001).

In normal primates, SOA neurons do not modulate during the performance of a saccade task on a tangent screen at far (Mays 1984). It is clear that the firing rates of the neurons in our sample were not constant, even in the absence of a fixation switch (see Figs. 1, 5, and 6 for examples). The noisy rate-position curves (see Fig. 1) and the inconsistent position sensitivities in the dynamic analyses suggest that large fluctuations in the tonic firing rate may not always lead to observable changes in horizontal strabismus angle. With these considerations in mind, we sought to quantify the variability in firing rate for a given viewing eye condition (i.e., right eye fixating or left eye fixating). To obtain a normalized estimate of this variability, we computed, for each neuron in our sample, the coefficient of variation for both viewing eye conditions. For the left eye viewing condition, the mean coefficient of variation (across all neurons) was 0.48. For the right eye viewing condition, the mean was 0.46. From these data, it is clear that, for the typical SOA neuron, firing rate commonly varied by 40–50% of the mean, even when the viewing eye was held constant and even though the animal was performing a saccade task on a tangent screen at far (57 cm).

Fixation-switching saccades were observed in all four monkeys. However, only monkey XT1 typically made such movements with enough frequency to permit statistical analysis. For each neuron, the dynamic model fits were performed on fixation-switching saccades only if a minimum of 5 such movements occurred. This criterion was satisfied for 34 neurons, including 27 from monkey XT1, 2 from monkey XT2, and 5 from monkey ET2. The results of this analysis are shown in the inset in the top-right corner of Fig. 10. The vergence velocity term was significant for 12 neurons (35%). Only 1 neuron showed a velocity sensitivity >0.5.

DISCUSSION

Das (2012) recorded SOA neurons while monkeys with experimentally induced exotropia performed fixation and smooth pursuit tasks on a tangent screen. He reported that the tonic firing rates of SOA neurons modulate during changes in horizontal strabismus angle if they accompanied switches of the fixating eye but not if they were associated with A patterns. The present data confirm and extend those results in at least three respects. First, we have found that a similar pattern exists for saccades; in general, tonic firing rates do not typically change following horizontally disconjugate saccades in the absence of a fixation switch (consistent with hypothesis 2a). Second, as far as we are aware, the present study is the first to show that a subset of SOA neurons carry signals related to vergence velocity while monkeys with pattern strabismus perform oculomotor tasks on a tangent screen (hypothesis 3). Third, the present study was the first to show that the sensitivity to horizontal strabismus angle is weaker in monkeys with esotropia than the vergence position sensitivity in normal animals. Thus our data were consistent with hypothesis 1.

Abnormalities of rate-position curves in SOA neurons in strabismus (hypothesis 1).

One might predict that near-response cells would show abnormally strong activity in esotropia. Quantitatively, this hypothesis predicts that linear fits to the relationship between static horizontal strabismus angle and firing rate would result in abnormally high slopes and/or y-intercepts in esotropia compared with normal monkeys. However, the drive from near-response cells in SOA to medial rectus motoneurons is not the only factor that influences the angle of misalignment. For example, altered contractility of the extraocular muscles can also influence the strabismus angle (two recent reviews: Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017). In addition, abducens motoneurons (and, paradoxically, internuclear neurons) show decreased firing rates during convergence (Gamlin et al. 1989). Thus the horizontal strabismus angle at any given moment is influenced by the vergence-related drive to medial rectus motoneurons and abducens motoneurons. Thus the present data do not definitively resolve the complex issue of what causes a particular individual to develop esotropia or exotropia.

One limitation of the present study was that botulinum toxin injections were used to induce strabismus in two of our monkeys (XT2 and ET2) and monkey XT1 underwent bilateral medial rectus tenotomy during the 1st wk of life. Only monkey ET1 had a true sensory-induced strabismus, and we were only able to record seven neurons from this animal. This raises the possibility that abnormalities of the eye muscles might have caused shifts in the vergence rate-position curves. In particular, comparisons of y-intercepts between esotropes and exotropes might produce very different results if all animals have sensory-induced strabismus. Thus a comparison of the thresholds or y-intercepts of vergence rate-position curves in esotropia vs. exotropia, using monkeys with sensory-induced strabismus, would be a valuable addition to the literature. With these caveats in mind, the present results are consistent with the hypothesis that the loss of a crucial input to the vergence system, binocular disparity, can lead to weaker modulation of SOA neurons in both esotropia and exotropia.

Das (2012) reported that, during vertical smooth pursuit, the firing rates of SOA neurons are not correlated with changes in horizontal strabismus angle that result from A patterns. This author suggested that, in pattern strabismus, abnormalities within the brain stem circuits responsible for saccades and smooth pursuit cause the horizontal misalignment to vary with vertical eye position. Our results are consistent with this previous study: during saccades with vertical components, the firing rates of SOA neurons sometimes change but not always in the direction one would expect based on the sensitivity to static horizontal strabismus angle (see Fig. 1B: compare the two saccades highlighted with blue rectangles). This is, undoubtedly, part of the reason why the rate-position curves tend to be noisy in strabismus (see Fig. 2). In infantile strabismus, the vergence system is chronically deprived of one of the major sensory inputs driving modulation of SOA neurons, binocular disparity (two recent reviews: Das 2016; Walton et al. 2017). We suggest that, as a result of this, near- and far-response cells in SOA fail to develop normal tuning properties. In normal monkeys, SOA neurons display a range of sensitivities to disparity and accommodative vergence (Mays and Gamlin 1995; Zhang et al. 1992). Thus it is possible that the loss of one of the two major sensory inputs to the system results in disagreement between individual SOA neurons about what the current vergence angle should be, which would also increase the noise in the rate-position curves (see Fig. 2). It is also possible that, in the absence of normal binocular disparity signals, SOA neurons that would normally encode disparity vergence are driven, instead, by inappropriate signals such as visual signals from only one eye. All of these factors would be likely to disturb the relationship between tonic firing rate and horizontal strabismus angle, resulting in weaker correlations and smaller slopes.

It has recently been reported that, in normal monkeys, adaptation to disconjugate eye misalignment is a binocular process, presumably mediated by the vergence system (Schultz and Busettini 2013). In strabismus, the necessary error signal (disparity) is weak or absent. This might explain why modulation of SOA activity influences strabismus angle but the vergence system is unable to realign the eyes following horizontally disconjugate saccades.

Role of SOA activity in horizontal saccade disconjugacy in strabismus (hypothesis 2).

The observation that there was little or no change in tonic firing rates following horizontally disconjugate saccades on a tangent screen in the absence of a fixation switch is consistent with several recent studies that have suggested that abnormalities exist within brain stem structures that generate saccadic commands (Ghasia et al. 2015; Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2013). In this view, abnormalities in premotor structures such as paramedian pontine reticular formation and rostral interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus cause the saccadic system to send different commands to the two eyes. The present study found no evidence that the slow vergence system is primarily responsible for horizontal saccade disconjugacy in the absence of a fixation switch. Overall, the SOA activity during these movements did not resemble what is observed during disjunctive saccades in normal primates (see Fig. 10 and Pallus et al. 2018). However, the fact that a small vergence velocity sensitivity was found for many of the neurons in our sample suggests that SOA activity may have an influence, particularly on the dynamics of horizontal disconjugacy. We observed a slight but fairly consistent decrement in firing rate during the Intrasaccadic Epoch. Since near-response cells directly drive medial rectus motoneurons (Zhang et al. 1992), it seems likely that this has a small influence on the dynamics of saccade disconjugacy. A decrease in the firing rates of near-response cells during saccades, for example, might tend to enhance divergence transients (Collewijn et al. 1988; Pallus et al. 2018). It is also possible that idiosyncratic firing rate modulation during the performance of a saccade task on a tangent screen effectively adds noise but, otherwise, has little overall impact on horizontal saccade disconjugacy.

When normal monkeys make disjunctive saccades between targets that differ in both direction and distance, the fast intrasaccadic vergence is not encoded by SOA neurons, but the tonic firing rates of these near- and far-response cells do show the appropriate modulation to maintain the new vergence angle (Pallus et al. 2018). This was not the case for SOA neurons in our strabismic animals for horizontally disconjugate saccades in the absence of a fixation switch. In this respect, also, the present results suggest that it would be incorrect to view horizontal saccade disconjugacy in strabismus (i.e., while tracking targets on a tangent screen) as a contextually inappropriate, combined saccade-slow vergence movement. Different results might be obtained from strabismic animals if one recorded from SOA neurons during saccades between targets that differ in both direction and distance, particularly if the targets offered a robust accommodative stimulus.

We have previously demonstrated that saccade disconjugacy in strabismus is at least partially attributable to abnormalities within the brain stem saccadic circuitry. If this is correct, then one potential interpretation of the above results is that the contribution of SOA to saccade horizontal disconjugacy is mostly masked by abnormalities in a parallel circuit (i.e., superior colliculus-paramedian pontine reticular formation-abducens), leaving only weak correlations.

In strabismus, there are often visual acuity differences between the two eyes. These differences could be due to loss of influence at a cortical level (amblyopia). When strabismic subjects make fixation-switching saccades, it is possible that the binocularly abnormal visual system causes the vergence system to “mistake” visual acuity differences between the two eyes for accommodative blur. If this is correct, then fixation switches would lead to changes in horizontal strabismus angle because these movements inappropriately engage the accommodative vergence system. It has previously been demonstrated that the tonic firing rates of SOA neurons change following fixation-switching saccades in strabismic monkeys (Das 2012). In our sample of recordings from strabismic monkeys, 12/34 neurons showed statistically significant vergence velocity sensitivity during fixation-switching saccades. The velocity sensitivities tended to be small, but this was also true of SOA neurons recorded from normal monkeys during a saccade-vergence task (Pallus et al. 2018).

Variability in tonic firing rate and vergence-only movements (hypothesis 3).

It is difficult to determine the cause of fluctuations in tonic firing rate that occur in the absence of a fixation switch. One possibility is that they might be driven by accommodative instability. In a recent preliminary report, Joshi (2016) found correlations between accommodative microfluctuations and fixation instability in strabismic monkeys but not in normal controls. Since some SOA neurons carry signals related to accommodation (Zhang et al. 1992), it seems likely that this relates to contextually inappropriate modulations of SOA activity in the present study. Whatever the cause of these fluctuations in firing rate, they were often associated with the vergence-only movements that were frequently observed, in all four monkeys, during fixation of static targets at far. Although the majority of these movements were small (<2°), most were still outside the range of what is typically observed in normal animals (Upadhyaya et al. 2017b), and a few vergence-only movements were large (>8°). For half of the neurons in our sample, these contextually inappropriate slow vergence movements were associated with detectable vergence-velocity signals (consistent with hypothesis 3). Because of the small range of vergence-only amplitudes in many of our recordings, the present results may have underestimated the number of SOA neurons that are sensitive to vergence velocity during vergence-only movements.

In summary, the present results are consistent with, and extend, previous studies that have suggested that, in monkeys with strabismus induced in infancy, saccade disconjugacy is largely attributable to abnormalities within the brain stem saccadic circuitry (Ghasia et al. 2015; Walton and Mustari 2015; Walton et al. 2013). The present results suggest that a subset of SOA neurons do show contextually inappropriate modulation during visually guided tracking of targets on a tangent screen. This modulation might have an influence on disconjugacy. Furthermore, our results also suggest that inappropriate modulation of SOA neuronal activity contributes to fixation instability in strabismus.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Eye Institute Grants EY-024848 (to M. M. G. Walton), EY-06069 (to M. Mustari), and P30-EY-001730 (Vision Core Grant) and Office of Research Infrastructure Programs Unrestricted Award P51-OD-010425 to Department of Ophthalmology, University of Washington, from Research to Prevent Blindness.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.M.G.W. conceived and designed research; A.P. and M.M.G.W. performed experiments; A.P. and M.M.G.W. analyzed data; A.P., M.M.G.W., and M.M. interpreted results of experiments; A.P. and M.M.G.W. prepared figures; M.M.G.W. drafted manuscript; A.P., M.M.G.W., and M.M. edited and revised manuscript; A.P., M.M.G.W., and M.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Amore FM, Fasciani R, Silvestri V, Crossland MD, de Waure C, Cruciani F, Reibaldi A. Relationship between fixation stability measured with MP-1 and reading performance. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 33: 611–617, 2013. doi: 10.1111/opo.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci MP, Kapoula Z, Yang Q, Roussat B, Brémond-Gignac D. Binocular coordination of saccades in children with strabismus before and after surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43: 1040–1047, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LL, Walton MM. Head movement evoked by electrical stimulation in the supplementary eye field of the rhesus monkey. J Neurophysiol 94: 4502–4519, 2005. doi: 10.1152/jn.00510.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernick MR, LaBudde RA. An Introduction to Bootstrap Methods with Applications to R. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Collewijn H, Erkelens CJ, Steinman RM. Binocular co-ordination of human horizontal saccadic eye movements. J Physiol 404: 157–182, 1988. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das VE. Cells in the supraoculomotor area in monkeys with strabismus show activity related to the strabismus angle. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1233: 85–90, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das VE. Responses of cells in the midbrain near-response area in monkeys with strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 3858–3864, 2012. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das VE. Strabismus and the oculomotor system: insights from macaque models. Annu Rev Vis Sci 2: 37–59, 2016. doi: 10.1146/annurev-vision-111815-114335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison RC, Hinkley DV. Bootstrap Methods and their Application. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511802843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleuriet J, Walton MM, Ono S, Mustari MJ. Electrical microstimulation of the superior colliculus in strabismic monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57: 3168–3180, 2016. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-19488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Tusa RJ, Mustari MJ, Das VE. Horizontal saccade disconjugacy in strabismic monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 3107–3114, 2007. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs AF, Robinson DA. A method for measuring horizontal and vertical eye movement chronically in the monkey. J Appl Physiol 21: 1068–1070, 1966. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1966.21.3.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamlin PD, Gnadt JW, Mays LE. Abducens internuclear neurons carry an inappropriate signal for ocular convergence. J Neurophysiol 62: 70–81, 1989. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasia FF, Shaikh AG, Jacobs J, Walker MF. Cross-coupled eye movement supports neural origin of pattern strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56: 2855–2866, 2015. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi AC. Correlation of fixation instability and accommodative microfluctuations in normal and strabismic monkeys (Abstract). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57: 4577, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Judge SJ, Richmond BJ, Chu FC. Implantation of magnetic search coils for measurement of eye position: an improved method. Vision Res 20: 535–538, 1980. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(80)90128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoula Z, Bucci MP, Eggert T, Garraud L. Impairment of the binocular coordination of saccades in strabismus. Vision Res 37: 2757–2766, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(97)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon RV, Ciuffreda KJ, Stark L. Dynamic vergence eye movements in strabismus and amblyopia: asymmetric vergence. Br J Ophthalmol 65: 167–176, 1981. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.3.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon RV, Ciuffreda KJ, Stark L. Dynamic vergence eye movements in strabismus and amblyopia: symmetric vergence. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 19: 60–74, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell GF, Lemij HG, Collewijn H. Conjugacy of saccades in deep amblyopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36: 2514–2522, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays LE. Neural control of vergence eye movements: convergence and divergence neurons in midbrain. J Neurophysiol 51: 1091–1108, 1984. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.5.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays LE, Gamlin PD. Neuronal circuitry controlling the near response. Curr Opin Neurobiol 5: 763–768, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays LE, Porter JD, Gamlin PD, Tello CA. Neural control of vergence eye movements: neurons encoding vergence velocity. J Neurophysiol 56: 1007–1021, 1986. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.4.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallus AC, Walton MM, Mustari MJ. Response of supraoculomotor area neurons during combined saccade-vergence movements. J Neurophysiol 119: 585–596, 2018. doi: 10.1152/jn.00193.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DA. Oculomotor unit behavior in the monkey. J Neurophysiol 33: 393–403, 1970. doi: 10.1152/jn.1970.33.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz KP, Busettini C. Short-term saccadic adaptation in the macaque monkey: a binocular mechanism. J Neurophysiol 109: 518–545, 2013. doi: 10.1152/jn.01013.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre PA, Cullen KE. Dynamics of abducens nucleus neuron discharges during disjunctive saccades. J Neurophysiol 88: 3452–3468, 2002. doi: 10.1152/jn.00331.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvestre PA, Cullen KE. Quantitative analysis of abducens neuron discharge dynamics during saccadic and slow eye movements. J Neurophysiol 82: 2612–2632, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tychsen L, Scott C. Maldevelopment of convergence eye movements in macaque monkeys with small- and large-angle infantile esotropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 3358–3368, 2003. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya S, Meng H, Das VE. Electrical stimulation of superior colliculus affects strabismus angle in monkey models for strabismus. J Neurophysiol 117: 1281–1292, 2017a. doi: 10.1152/jn.00437.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyaya S, Pullela M, Ramachandran S, Adade S, Joshi AC, Das VE. Fixational saccades and their relation to fixation instability in strabismic monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58: 5743–5753, 2017b. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-22389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn MR, Cullen KE. Dynamic characterization of agonist and antagonist oculomotoneurons during conjugate and disconjugate eye movements. J Neurophysiol 102: 28–40, 2009. doi: 10.1152/jn.00169.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MM, Mustari MJ. Abnormal tuning of saccade-related cells in pontine reticular formation of strabismic monkeys. J Neurophysiol 114: 857–868, 2015. doi: 10.1152/jn.00238.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MM, Mustari MJ. Comparison of three models of saccade disconjugacy in strabismus. J Neurophysiol 118: 3175–3193, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00983.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MM, Ono S, Mustari M. Vertical and oblique saccade disconjugacy in strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55: 275–290, 2014. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MM, Ono S, Mustari MJ. Stimulation of pontine reticular formation in monkeys with strabismus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 7125–7136, 2013. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MM, Pallus A, Fleuriet J, Mustari MJ, Tarczy-Hornoch K. Neural mechanisms of oculomotor abnormalities in the infantile strabismus syndrome. J Neurophysiol 118: 280–299, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00934.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Mays LE, Gamlin PD. Characteristics of near response cells projecting to the oculomotor nucleus. J Neurophysiol 67: 944–960, 1992. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.4.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]