Abstract

Marine forests dominated by macroalgae have experienced noticeable regression along some temperate and subpolar rocky shores. Along continuously disturbed shores, where natural recovery is extremely difficult, these forests are often permanently replaced by less structured assemblages. Thus, implementation of an active restoration plan emerges as an option to ensure their conservation. To date, active transplantation of individuals from natural and healthy populations has been proposed as a prime vehicle for restoring habitat-forming species. However, given the threatened and critical conservation status of many populations, less invasive techniques are required. Some authors have experimentally explored the applicability of several non-destructive techniques based on recruitment enhancement for macroalgae restoration; however, these techniques have not been effectively applied to restore forest-forming fucoids. Here, for the first time, we successfully restored four populations of Cystoseira barbata (i.e., they established self-maintaining populations of roughly 25 m2) in areas from which they had completely disappeared at least 50 years ago using recruitment-enhancement techniques. We compared the feasibility and costs of active macroalgal restoration by means of in situ (wild-collected zygotes and recruits) and ex situ (provisioning of lab-cultured recruits) techniques. Mid/long-term monitoring of the restored and reference populations allowed us to define the best indicators of success for the different restoration phases. After 6 years, the densities and size structure distributions of the restored populations were similar and comparable to those of the natural reference populations. However, the costs of the in situ recruitment technique were considerably lower than those of the ex situ technique. The restoration method, monitoring and success indicators proposed here may have applicability for other macroalgal species, especially those that produce rapidly sinking zygotes. Recruitment enhancement should become an essential tool for preserving Cystoseira forests and their associated biodiversity.

Keywords: conservation, cost-effective restoration, Cystoseira, Fucales, human impacts, marine forests, recruitment enhancement, seaweed restoration

Introduction

Canopy-forming brown macroalgae, such as kelps (Laminariales) and fucoids (Fucales), are habitat-forming species in the intertidal and subtidal zones of most temperate and subpolar regions (Steneck et al., 2002; Schiel and Foster, 2006). These macroalgae create structurally complex communities that have several similarities with terrestrial forests (Dayton et al., 1984, 1992; Ballesteros et al., 2009; Reed and Foster, 2012; Gianni et al., 2013). In addition to playing a crucial role in coastal primary production and nutrient cycling, these marine forests increase the three-dimensional complexity and spatial heterogeneity of rocky bottoms, providing food, shelter, nurseries and habitat for many other species (e.g., fish, invertebrates and other algae); thus, they host high biodiversity (Mann, 1973; Seed and O’Connor, 1981; Dayton, 1985; Graham, 2004; Schiel and Foster, 2006).

Compared to many other structurally complex ecosystems around the world, marine forests are suffering from a small global decline on average, despite large regional variation in both the direction and magnitude of the changes, meaning that while global declines are small on average, local-scale declines can be severe (Krumhansl et al., 2016). In many areas, the cumulative impacts of different human pressures, such as habitat destruction, pollution, overgrazing, invasive species and ocean warming, have largely disturbed canopy-forming macroalgae in recent decades (Steneck et al., 2002; Thibaut et al., 2005; Airoldi and Beck, 2007; Connell et al., 2008; Ling et al., 2009; Vergés et al., 2014, 2016; Wernberg et al., 2016). As a result, vast underwater marine forests have gone missing from many coastal areas and are being replaced by simpler and less productive communities dominated by opportunistic taxa (such as turfs or barrens) (Benedetti-Cecchi et al., 2001; Thibaut et al., 2005; Connell et al., 2008; Mangialajo et al., 2008; Ling et al., 2009; Smale and Wernberg, 2013; Vergés et al., 2014; Valdazo et al., 2017). Although some giant kelp populations have been shown to recover quickly from local- to large-scale disturbances (Dayton et al., 1992; Edwards, 2004), this is not always the case for other giant kelp populations, not for other kelps (e.g., Dayton, 1973) or fucoids (Coleman et al., 2008; Sales et al., 2011; Smale and Wernberg, 2013). The low dispersal abilities of zygotes and/or spores have been blamed for the lack of fucoid population recovery (Kendrick and Walker, 1991; Chapman, 1995; Dudgeon and Petraitis, 2001). In these cases, and when populations have become extinct, natural recovery is almost impossible, and active restoration emerges as the only tool to recover these missing forests (Stekoll and Deysher, 1996; Terawaki et al., 2003; Falace et al., 2006; Susini et al., 2007; Sales et al., 2011; Campbell et al., 2014).

The Mediterranean Sea, a marine biodiversity hotspot, has experienced large alterations in its ecosystems (Coll et al., 2010; Lotze et al., 2011). Marine forests dominated by species of the genus Cystoseira (Fucales) are widespread on well-preserved Mediterranean rocky bottoms (Giaccone, 1973; Ballesteros, 1988, 1990a,b; Ballesteros et al., 1998, 2009; Zabala and Ballesteros, 1989; Sales et al., 2012). Despite not reaching the size of kelp or some other fucoids, Cystoseira species produce a dense canopy (rarely > 1 m high) creating a “forest-like” assemblage, with species growing in the understory that are not found without their presence. This is the reason we speak about Cystoseira forests.

Some Cystoseira forests have severely declined in recent decades (Cormaci and Furnari, 1999; Thibaut et al., 2005; Serio et al., 2006; Blanfuné et al., 2016). Since zygotes of Cystoseira species are very large (around 100–120 μm) and exhibit low dispersal abilities (Guern, 1962; Clayton, 1992), transplantation techniques have been used as a tool for environmental mitigation (Falace et al., 2006; Susini et al., 2007; Perkol-Finkel et al., 2012; Robvieux, 2013).

However, since most Cystoseira species are considered threatened or endangered by the Barcelona Convention (Annex II) (United Nations Environment Programme/Mediterranean Action Plan [UNEP/MAP], 2013), individual transplants from remaining populations are undesirable, and therefore, less invasive restoration actions are required (see Gianni et al., 2013 for a review). As a result, new recruits of certain fucoid species have been artificially obtained and monitored for one year (Stekoll and Deysher, 1996; Terawaki et al., 2003; Yatsuya, 2010; Yu et al., 2012; Falace et al., 2018), introducing the possibility of recruitment enhancement as a new strategy for restoring Cystoseira populations.

In this context, the general objective of this study is to provide and experimentally test non-destructive restoration methods that can lead to the establishment of self-sustaining Cystoseira populations and to describe the proper success indicators for the different restoration stages. Specifically, we describe two techniques using in situ and ex situ recruitment enhancement aimed at restoring populations of C. barbata, and the success of each is assessed by comparing restored and reference populations over six years. Moreover, because the success and broad-scale application of a restoration technique also depends on its cost feasibility, we also describe this key piece of information.

Materials and Methods

Species and Study Site

This study focuses on the species Cystoseira barbata (Stackhouse) C. Agardh, which typically develops in shallow and sheltered environments (Sales and Ballesteros, 2009) across the Mediterranean Sea. The reduction in its range is strongly correlated with human development (Thibaut et al., 2005, 2015; Bologa and Sava, 2006), and the species is classified as threatened under the Barcelona Convention (United Nations Environment Programme/Mediterranean Action Plan [UNEP/MAP], 2013). These features make C. barbata a perfect target species for restoration in places from which it has disappeared.

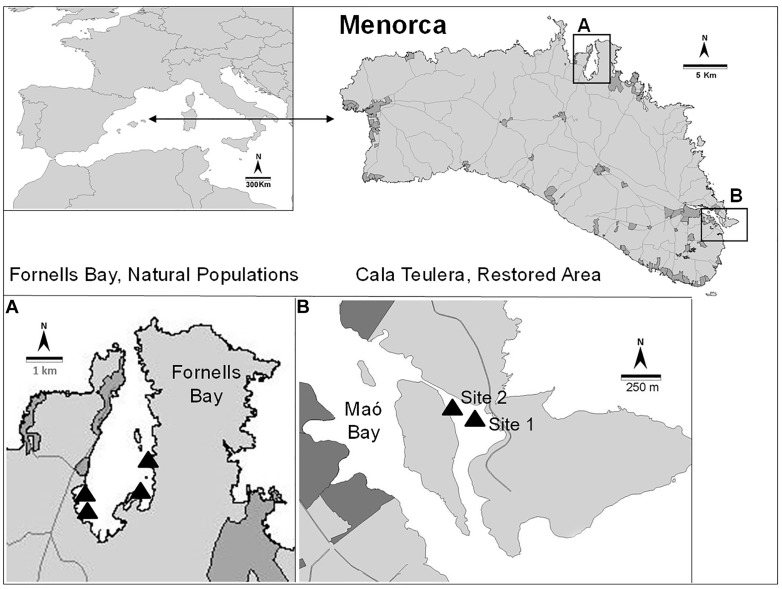

This study was conducted in Menorca (Balearic Islands, NW Mediterranean), which has been a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve since 1993. Most coastal areas in Menorca are well preserved and have limited urbanization. The coastal water quality is high, so the extent and cover of habitats dominated by Cystoseira species is outstanding (Sales and Ballesteros, 2009). Cystoseira barbata naturally makes small patches (usually around a few square meters) in very sheltered and shallow environments. This species is extremely rare not only in Menorca but also in other Mediterranean areas (Gómez-Garreta et al., 2002) because there are very few places matching its environmental requirements, with the exception of the northern Adriatic Sea. Cystoseira barbata is present in Fornells Bay (Menorca), one of the few places where the environmental conditions are suitable for its development. However, this species was reported from Cala Teulera (39°52′40.64″ N, 4°18′22.03′ E; Bay of Maó, Figure 1) in the XVIII century (Rodríguez-Femenías, 1888), but it disappeared from this area due to direct dumping of urban and industrial sewage into the bay during the 1970s, leading to impaired water quality. A sewage outfall was built in 1980, and waste waters were diverted into the open sea (Hoyo, 1981). However, no recovery of the C. barbata populations was detected during the next 30 years (Sales et al., 2011). Nevertheless, Cala Teulera still shelters a reduced meadow of the seagrass Cymodocea nodosa and some stands of Cystoseira compressa var. pustulata and Cystoseira foeniculacea f. tenuiramosa. In contrast, Fornells Bay (40°2′10.12” N, 4°7′43.24′ E; Figure 1) continues to be characterized by low human influence and extensive sheltered seagrass meadows (e.g., Posidonia oceanica, C. nodosa, Zostera noltii) (Delgado et al., 1997) and healthy Cystoseira spp. forests, including the only preserved C. barbata populations from Menorca (Sales and Ballesteros, 2009). For this reason, the stands in Fornells Bay were selected as donor populations to restore two different sites in Cala Teulera (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Location of the reference populations (A) and the restored area (B).

Applied Restoration Techniques

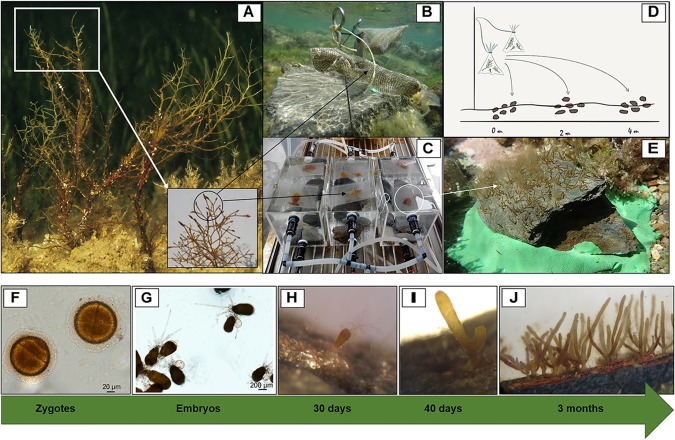

Two different restoration techniques involving in situ and ex situ recruitment enhancement were experimentally tested to promote C. barbata recovery. Both techniques are considered non-destructive since they only rely on harvesting a small proportion (< 5%) of reproductive fertile branchlets from wild individuals. Both donor and restored sites were situated between depths of 0.2 m and 1 m. In situ recruitment consisted of collecting fertile apical branchlets (March 2011) from the donor populations (Fornells Bay) that were then transported to the restoration sites and placed in dispersal bags that were 8 cm wide and 10 cm long (Figures 2A,B) and made of 36% fiberglass and 64% PVC with a mesh size of 1.20 × 1.28 mm.

FIGURE 2.

Experimental setup and zygote development into recruits. (A) Fertile thalli and branchlets from natural populations, (B) dispersal bags placed in situ, (C) dispersal bags placed in culture tanks (ex situ), (D) dispersion range capacity under in situ recruitment, and (E) placement of ex situ recruits in the area to be restored. Zygote and embryo development into recruits from ex situ cultures (F–J). (F) Zygotes (1 day), (G) embryos adhered to the substrate by rhizoids (1 week), (H) embryos developing into recruits (1 month, 200–400 μm), (I) first branching of the recruit (1.5 months, 400–600 μm), and (J) fully developed recruits (3 months, 5–15 mm).

Bags were tied to a pick and directly fixed at a vertical distance of 0.25 cm from the bottom using a hammer (Figure 2B). Eight bags (two for each pick) containing approximately twenty fertile receptacles each were placed at each of the two selected restoration sites at distances of 2–3 m from each other. At both sites, six natural flat schist stones with similar surface areas (approximately 0.04 m2) were collected, cleaned of organisms and sediment and randomly placed in radii from 0.1 to 4 m around the dispersal bags to promote C. barbata settlement. We used stones adjacent to our study areas, and not from the same area, to avoid disturbing the study site when cleaning the stones from organisms and sediment. The stones where cleaned to provide free substrate and avoid competition at the first stages of development of new recruits. After 4 days, the dispersal bags were removed from both restored sites.

Ex situ recruitment consisted of acquiring a supply of zygotes and culturing settlers in the laboratory. Fertile apical branchlets (around 2–3 cm in length) from the donor populations (March 2011, Fornells Bay) were collected and placed in plastic bags without seawater and transported to the laboratory under cold and dark conditions. Once in the laboratory, the bags containing the fertile branchlets were stored in the fridge (at 4°C and in dark conditions) for 12 h to promote zygote liberation. Concurrently, 16 natural flat schist stones with similar surface areas (approximately 0.04 m2) were placed at the bottom of ten 12-L tanks filled with filtered seawater, and fertile apical branchlets of C. barbata were placed on dispersal bags floating on the water surface of each tank for 4 days (Figures 2A,C). Moreover, some glass slides were placed on top of and between the stones to enable microscopically monitoring of zygote development during the first months (Figures 2F–J). zygote development to be microscopically monitored during the first month. For the first 4 days, the hydrodynamic conditions of the tank were kept as stable as possible to facilitate zygote settlement. Afterward, zygotes were cultured in a closed-water circuit with a renovation rate of 2 L per day using natural seawater at 21°C and natural light conditions. Seawater temperature was controlled with refrigerators (Hailea Chiller HC 500 A of Hailea). After 3 months (June 2011), stones with C. barbata recruits were transported to the restoration sites and six stones were placed at a distance of 25 m from the in situ restored area at each site (Figure 2E). It was not necessary to fix the stones since the restoration areas were extremely sheltered and the stones were heavy enough to prevent any movement.

Monitoring the Restored and Reference Populations

After installing the in situ and ex situ recruitment set ups, both sites were visited monthly to ensure that the experiment was properly maintained. After five months, both in situ and ex situ recruits were large enough to allow visual density and height measurements. Then, the density (the total number of individuals per 0.04 m2) and the size structure distribution (the length of the main axis) of C. barbata individuals from each stone (approximately 20 × 20 cm) were monitored in situ twice in 2011 (August and November) and once during 2012, 2013, 2014, 2016, and 2017 (August) at each restored site and for each restoration technique.

At the beginning of the experiment, 3 natural C. barbata populations (Fornells Bay; Figure 1) were also selected as reference populations for comparison with the restored populations. The densities and size structure distributions of each reference population were monitored in 20 randomly distributed, 20 × 20-cm quadrats at the beginning and end of the experiment (i.e., August 2011, 2016, and 2017).

Dispersal Capacity of the in situ Recruitment Method

At the same time, a new experiment was set up to explore the extension range of the in situ recruitment method. We studied the dispersion capacity of the C. barbata zygotes. For this purpose, we fixed a new pick (with 2 dispersal bags each) at each site, and six stones (approximately 0.04 m2 each) were placed just below the dispersal bags (0 m) along with six at a distance of 2 m, and finally six at a distance of 4 m. The dispersal bags were removed after 4 days, and the number of recruits from each stone was counted in August 2011 (Figure 2D).

Data Analysis

Comparison of Techniques

To compare the two restoration techniques, the mean densities and size distribution at both restored sites were evaluated. The mean density (number of individuals/0.04 m2) over time was analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with technique (2 levels: ex situ vs. in situ), site (2 levels: site 1 and site 2) and time (7 levels) as fixed factors, and stone as a random factor. Descriptive statistics were also calculated for the size structure distribution (the skewness and kurtosis) of restored populations and compared among both techniques and sites. The significance of the skewness and kurtosis values was calculated according to Sokal and Rohlf (1995).

Restoration Success

Restoration success was analyzed by comparing the final densities and size structures between restored and reference populations. The final density (August 2017) of restored populations was compared with that of reference populations by means of a generalized linear model (GLM) with one fixed factor with two levels (restored vs. control). Changes in the size structure distributions of the restored and reference populations over time were plotted using non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) to visualize their progression. The relative percentage of individuals in each size class (in 1-cm intervals) was the variable in the data matrix, and the Bray-Curtis distance (Bray and Curtis, 1957) with a dummy variable (= 1) was used to construct the similarity matrix.

Dispersal Capacity

Finally, the range in dispersal capacity obtained with the in situ method was analyzed using GLM, with site (2 levels) and distance from the dispersal bag (3 levels) as fixed factors. Pair-wise comparisons were also performed between distances.

GLMs and GLMMs are suitable for this kind of data since GLMs can handle non-normal data (Bolker et al., 2009) and GLMMs combine the properties of GLMs and linear mixed models, which incorporate random effects and therefore can cope with repeated measures over time (Pinheiro and Bates, 2000). All analyses were performed using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015) (Bates et al., 2015) for R software (R Core Team, 2016) and the statistical software Primer & Permanova v.6 (Clarke and Gorley, 2006).

Costs

We compared the cost of restoring a population (25 m2) using the ex situ and in situ methods, considering the travel, transportation, personnel and material expenses (similarly to Carney et al., 2005). We did not consider the long-term monitoring costs since these costs are equivalent for the two techniques.

Results

Comparison of Techniques

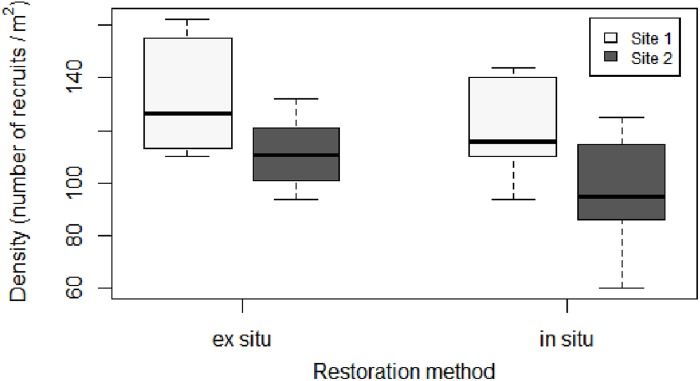

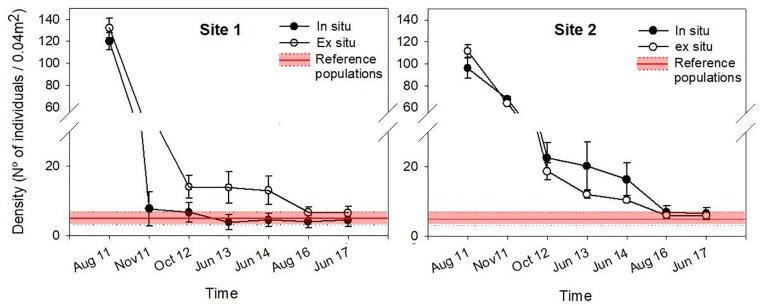

The density of recruits was similar between the two restoration techniques (Figures 3, 4 and Table 1). The mean initial densities ranged between 120 ± 7 recruits/0.04 m2 (site 1) and 96 ± 9 recruits/0.04 m2 (site 2) in the in situ experiment and between 132 ± 2 recruits/0.04 m2 (site 1) and 111 ± 9 recruits/0.04 m2 (site 2) in the ex situ experiment (Figure 3). No recruits were observed outside of the free substrate (stones) with the in situ method. The densities of the two restored populations greatly decreased during the first year but remained more stable afterward (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Boxplot of initial density (number of recruits/0.04 m2) for each restoration technique and site. In the boxplot, the bold horizontal line indicates the median value (Q2); the box marks the interquartile distances, Q1 and Q3; and the whiskers mark the values that are less than Q3+1.5∗IQR but greater than Q1–1.5∗IQR.

FIGURE 4.

Mean density (± SE) through time for each restoration technique at each site. Reference population densities are represented in red, considering the mean and standard deviation values obtained from the reference populations in 2011, 2016, and 2017.

Table 1.

Results of GLMM comparing the density (number of individuals/0.04 m2) through time in relation to the restoration techniques (in situ vs. ex situ).

| Factor | df | F-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | 1 | 0.11 | 0.43 |

| Site | 1 | 2.67 | 0.17 |

| Time | 6 | 796.26 | < 0.0001 |

| Technique ∗ Site | 1 | 2.94 | 0.66 |

| Technique ∗ Time | 6 | 0.48 | < 0.0001 |

| Site ∗ Time | 6 | 42.14 | < 0.0001 |

| Site ∗ Technique ∗ Time | 6 | 21.25 | < 0.0001 |

For each factor, we report the degrees of freedom and the F- and p-values. The significant values are highlighted in bold in the table.

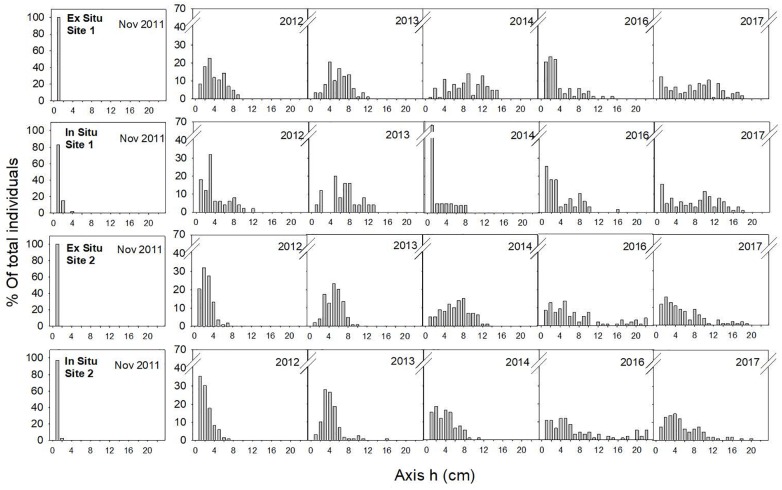

In November 2011, the main axes of almost all the individuals measured 1 cm, and one year later (August 2012), the skewness of the size-class structure was significantly positive, indicating the prevalence of small size-classes in the population. However, few individuals had reached axis lengths greater than 10 cm (Table 2 and Figure 5). Two years later (2013), all populations were approximately bell shaped and symmetric, with a large proportion of individuals having axis lengths between 2 and 5 cm, although some fertile individuals reached axis lengths of 14–16 cm (Table 2 and Figure 5).

Table 2.

Characteristics of restored C. barbata populations through time and in relation to the restoration technique and site (N: number of Cystoseira individuals; h: length of the main axis (cm); g1: skewness; g2: kurtosis; Sig: significance of skewness and kurtosis values).

| Date | Method | site | N | mean h | max h | g1 | SE g1 | sig. g1 | g2 | SE g2 | sig. g2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 Aug | in situ | 1 | 720 | 0,5 | 0,5 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2 | 576 | 0,5 | 0,5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| ex situ | 1 | 793 | 0,5 | 0,5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 2 | 669 | 0,5 | 0,5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| 2011 Nov | in situ | 1 | 46 | 0,83 | 4 | 3,25 | 0,35 | 9,28 | 13,59 | 0,69 | 19,76 |

| 2 | 406 | 0,6 | 1,5 | 2,25 | 0,12 | 18,58 | 4,44 | 0,24 | 18,37 | ||

| ex situ | 1 | 214 | 0,5 | 0,5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| 2 | 384 | 0,5 | 0,5 | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| 2012 | in situ | 1 | 40 | 3,73 | 12 | 1,09 | 0,37 | 2,92 | 0,54 | 0,73 | 0,74 |

| 2 | 135 | 1,99 | 6,5 | 1,15 | 0,21 | 5,51 | 0,81 | 0,41 | 1,96 | ||

| ex situ | 1 | 84 | 3,89 | 8,5 | 0,4 | 0,26 | 1,52 | -0,78 | 0,52 | -1,50 | |

| 2 | 112 | 2,34 | 6,5 | 0,96 | 0,23 | 4,20 | 1,42 | 0,45 | 3,13 | ||

| 2013 | in situ | 1 | 26 | 6,81 | 13 | -0,09 | 0,46 | -0,20 | -0,31 | 0,89 | -0,35 |

| 2 | 128 | 3,95 | 10,5 | 1,46 | 0,21 | 6,82 | 3,5 | 0,42 | 8,24 | ||

| ex situ | 1 | 88 | 5,68 | 12 | 0,19 | 0,26 | 0,74 | -0,09 | 0,51 | -0,18 | |

| 2 | 103 | 4,88 | 10 | 0,1 | 0,24 | 0,42 | -0,01 | 0,47 | -0,02 | ||

| 2014 | in situ | 1 | 22 | 1,98 | 8 | 1,49 | 0,49 | 3,03 | 0,98 | 0,95 | 1,03 |

| 2 | 91 | 3,75 | 11 | 0,63 | 0,25 | 2,49 | 0,1 | 0,50 | 0,20 | ||

| ex situ | 1 | 85 | 8,55 | 15 | -0,15 | 0,26 | -0,57 | -0,93 | 0,52 | -1,80 | |

| 2 | 81 | 6,27 | 13 | -0,05 | 0,27 | -0,19 | -0,58 | 0,53 | -1,10 | ||

| 2016 | in situ | 1 | 67 | 3,94 | 16 | 1,25 | 0,29 | 4,27 | 1,67 | 0,58 | 2,89 |

| 2 | 92 | 7,72 | 22 | 1,09 | 0,25 | 4,34 | -0,05 | 0,50 | -0,10 | ||

| ex situ | 1 | 68 | 3,92 | 15 | 1,47 | 0,29 | 5,06 | 1,62 | 0,57 | 2,82 | |

| 2 | 94 | 7,52 | 22 | 1,13 | 0,25 | 4,54 | 0,21 | 0,49 | 0,43 | ||

| 2017 | in situ | 1 | 103 | 7,7 | 17,5 | 0,007 | 0,24 | 0,03 | -1,17 | 0,47 | -2,48 |

| 2 | 110 | 5,54 | 20 | 1,29 | 0,23 | 5,60 | 1,68 | 0,46 | 3,68 | ||

| ex situ | 1 | 105 | 8,12 | 18 | 0,11 | 0,24 | 0,47 | -1 | 0,47 | -2,14 | |

| 2 | 103 | 5,72 | 19 | 1,24 | 0,24 | 5,21 | 1,04 | 0,47 | 2,21 | ||

These parameters are considered significant if the absolute value of the coefficient/standard error (SE) is greater than 2; the significant values are highlighted in bold in the table.

FIGURE 5.

Size-class frequency distribution of the restored populations over time for each site and restoration technique. The X-axis represents the size-classes (length of the main axis) in 1-cm intervals, and the Y-axis represents the relative frequency of each size-class.

In 2014, the size-class structures of the populations were symmetric and bell shaped, and most individuals were of intermediate size (Table 2 and Figure 5). One exception to this result was the population restored using the in situ method at site 1, where we found high mortality of large individuals but also high recruitment (Table 2 and Figure 5). These recruits were the result of new settlement events resulting from the already fertile restored individuals from 2013.

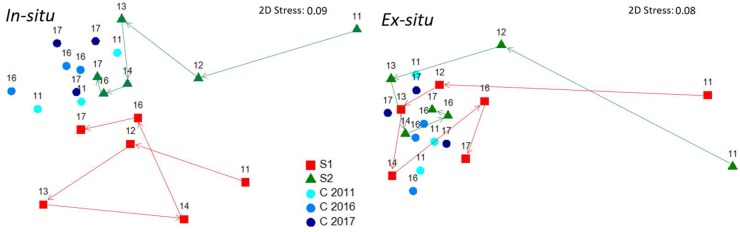

Restoration Success

In 2017, six years after the restoration action, the size of each of the four restored C. barbata patches was roughly 25 m2. When comparing the final densities of restored populations with the densities of the reference populations (August 2017), no significant differences were observed (F = 0.08, P = 0.49; Figure 4). The evolution of the size-class distribution through time resulting from both techniques, sites and reference populations is illustrated in the MDS (Figure 6). The reference populations are displayed on the left side of the MDS (from 2011 to 2017), while the restored populations progressed from the right side in 2011 to the left side, ultimately moving closer to the reference populations. In 2014, the in situ restored population from site 1 returned to the right side of the MDS due to the mortality of large individuals and the high recruitment that was experienced (Figure 6). In 2016, all populations were located close to the reference populations, and they remained stable in 2017 (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

MDS ordination plot of the path followed by restored and natural populations over time for both in situ and ex situ techniques, according to the size-class data of each population. Numbers depicted over each point are years.

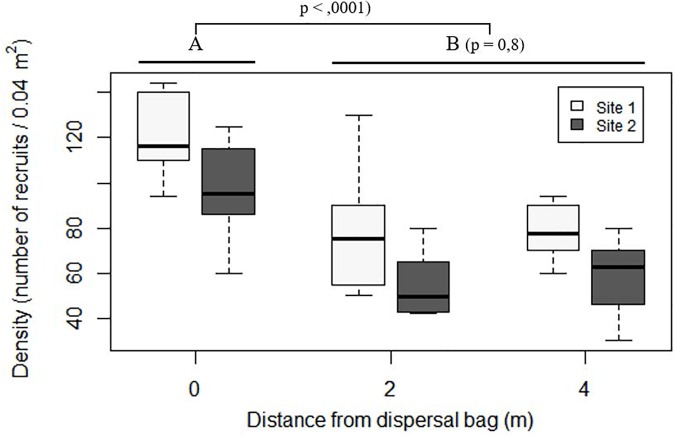

Dispersal Capacity

At both sites, stones situated below the dispersal bags (distance of 0 m) showed higher densities of C. barbata recruits than did those situated at distances of 2 and 4 m (P < 0.0001; Figure 7), while no differences were found between 2 and 4 m (P = 0.8; Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Boxplot of number of recruits on the stones placed in situ at increasing distances from the dispersal bags 5 months after their deployment. In the boxplot, the bold horizontal line indicates the median value (Q2); the box marks the interquartile distances, Q1 and Q3; and the whiskers mark the values that less than Q3+1.5∗IQR but greater than Q1–1.5∗IQR.

Costs

The cost of restoring 25 m2 of C. barbata forest ranged between 1,092 € using the in situ seeding technique and 2,665 € using the ex situ seeding technique (Table 3). The higher cost ascribed to the ex situ technique is related to the required infrastructure and the greater number of hours needed for culture maintenance.

Table 3.

Cost for the different concepts required to restore an area of 25 m2 depending on the restoration technique used.

| Concept | Rate | Cost | Total (€) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ex situ | |||

| Field time | |||

| Collection | 1h/2pax | 40€/h∗pax | 80 |

| Ex-plant | 3h/2pax | 40€/h∗pax | 240 |

| Transport | |||

| Car | 200 km | 0.40 €/km | 80 |

| Lab time | |||

| Set up culture | 4 h/2pax | 40€/h∗pax | 320 |

| Culture maintenance | 3 h/week∗pax | 40€/h∗pax | 1440 |

| Materials | |||

| Tanks | 10 | 25 € | 250 |

| Water pump | 1 | 60 € | 60 |

| Silicon Tubes | 5 m | 2 €/m | 10 |

| Epoxy | 2 | 70 €/kg | 140 |

| Aerator | 3 | 15 € | 45 |

| TOTAL | 2665 | ||

| In situ | |||

| Field time | |||

| Collection | 1h/2pax | 40€/h∗pax | 80 |

| Set up dispersal bags | 4h/2pax | 40€/h∗pax | 320 |

| Set up free substrate | 3h/2pax | 40€/h∗pax | 240 |

| Removal dispersal bags | 1h/2pax | 40€/h∗pax | 80 |

| Materials | |||

| Iron Stick | 16 | 7€/Pick | 112 |

| Epoxy | 2 | 70 €/kg | 140 |

| Transport | |||

| Car | 300 km | 0.40 €/km | 120 |

| TOTAL | 1092 | ||

Discussion

The present study is the first example of active restoration for locally extinct populations of habitat-forming fucoids using recruitment enhancement without adult transplantation of threatened populations, and these restored populations became self-sustaining, with densities and size-class structures comparable to those of the reference populations within five years. Active transplantation of adults or juveniles has been used as a mechanism to successfully restore habitat-forming species of fucoids (Susini et al., 2007; Campbell et al., 2014). The concept of recruitment enhancement has recently gained recognition as it applies to the restoration of threatened species (Yatsuya, 2010; Gianni et al., 2013; Falace et al., 2018). However, there have been only a few attempts at using this method, and most have been limited to the recruit stage with less than 1 year of monitoring (Stekoll and Deysher, 1996; Choi et al., 2000; Terawaki et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2012).

Here, we used recruitment enhancement methods to successfully restore a locally extinct C. barbata population with only one restoration action in 2011. Because the locally extinct population was unable to recover naturally, even thirty years after the primary stress had been ameliorated (Hoyo, 1981; Sales et al., 2011), we used seeding to overcome the limited natural dispersal rates that are typical of zygotes of the genus Cystoseira (Mangialajo et al., 2012), and we overrode the limited natural recruitment (Vadas et al., 1992; Capdevila et al., 2015) by cleaning the stones from organisms and sediment, providing free substrate to avoid competition. After six years, the sizes of each restored population was approximately 25 m2, which is comparable to the size-patches of natural C. barbata populations in Fornells Bay.

Recruitment was high and similar under both techniques, although a large proportion of recruits died during the first year. This sharp drop in density is common in natural populations due to the high natural sensitivity of the first fucoid life stages (Vadas et al., 1992; Irving et al., 2009). Although the density of individuals was similar between restored and reference sites in the second year following the restoration action, it took five years for the individuals of the restored populations to achieve comparable size-class structures to the reference ones. Thus, density is useful for monitoring success during the first period after a restoration action (recruits of settlers; here, 2 years), but after this stage, density should be complemented with other attributes, such as size structure, that will better describe the mature stage of the population.

Obtaining a Cystoseira population that reaches a well-represented and stable size distribution is the first goal for complete forest restoration. As for other structural species, the restoration success criteria should be linked to the recovery of the ecosystem function and services, and obtaining mature individuals that are able to self-sustain the new population is likely the first step for enhancing biodiversity and ecological processes. Complementary studies on the evolution of the associated community will probably elucidate whether the proposed indicators for population success may also be indicative of the overall recovery of ecosystem functions and services.

Both of the in situ and ex situ recruitment enhancement techniques applied here are probably suitable for other macroalgal species that produce large and fast-sinking zygotes with limited dispersion and that are poor competitors for space in their early stages (i.e., late-successional species). Thus, the techniques tested here could be used to restore other Mediterranean populations of Cystoseira spp., especially since the Council of Europe, specifically the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (United Nations Environment Programme/Mediterranean Action Plan [UNEP/MAP], 2013), pushes for active restoration to achieve a Good Environmental Status for a considerable number of habitats.

Knowledge of the biological traits of the target species will determine the choice between in situ and ex situ techniques. The in situ technique is especially recommended for species with high dispersal capacity, such as kelps, with a dispersal potential of hundreds of meters (Reed et al., 1988; Fredriksen et al., 1995). In contrast, the ex situ technique is more appropriate for species with a low dispersal capacity, such as C. amentacea, whose zygotes are not able to disperse a distance of even 40 cm (Mangialajo et al., 2012). Another benefit of the ex situ technique is that it minimizes the high mortality rates experienced by recruits and juveniles as a result of disturbances, predation or competition (Benedetti-Cecchi and Cinelli, 1992; Capdevila et al., 2015). The more the culture is prolonged, the more likely the critical life stages will be left behind, which ultimately enhances success. In our case, however, sources of mortality seemed to be rather irrelevant since the ex situ and the in situ survival rates were very similar during the first year. The ex situ technique should reduce the unpredictability of natural events and maximize success, while the in situ technique requires less infrastructure and maintenance, making it a cheaper option.

In summary, we provide a promising cost-effective method (consisting of two different techniques) that can be used to address the increasing need for the restoration of threatened species, especially fucoid forests. Moreover, we show that individual density is not a valid metric to assess the state of population recovery, and we propose the size distribution of the restored individuals as a suitable indicator of population maturity.

Author Contributions

EC and MS conceived the ideas, designed the methodology, and established the restoration action. All authors were involved in collecting data during the monitored period. JV, MS, and EC wrote the manuscript, and all authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave their final approval for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Eva María Vidal, Fiona Tomas, and María García in sampling and Jorge Santamaría in data analysis. We also acknowledge the D.G. d’Espais Naturals i Biodiversitat, the D.G. de Pesca i Medi Marí, and the Servei en Recerca i Desenvolupament del Govern de les Illes Balears for providing permits and the Jaume Ferrer Marine Station (Instituto Español de Oceanografía) for technical and facility support. EC and JV are members of the Marine Conservation Research Group (www.medrecover.org) from the Generalitat de Catalunya. American Journal Experts edited the English in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This project has received funding from the Horizon 2020 EU Research and Innovation Program under grant agreement No. 689518 (MERCES), the Fundación Biodiversidad under the framework of the project: “Conservación y restauración de poblaciones de especies amenazadas del género Cystoseira” and the Spanish Ministry Project ANIMA (CGL2016-76341-R, MINECO/FEDER, UE). This project has also been funded by Dirección General de Innovación e Investigación (Govern Illes Balears) and European Regional Development Fund (FEDER). JV has been funded by a IFUdG-2016 grant. The outputs presented here only reflect the views of the authors, and the EU cannot be held responsible for any use of the information contained therein.

References

- Airoldi L., Beck M. W. (2007). Loss, status and trends for coastal marine habitats of Europe. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 45 345–405. 10.1201/9781420050943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros E. (1988). Estructura y dinámica de la comunidad de Cystoseira mediterranea sauvegeau en Mediterráneo noroccidental. Inv. Pesq. 52 313–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros E. (1990a). Structure and dynamics of the community of Cystoseira zosteroides (Turner) C. Agardh (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) in the northwestern Mediterranean. Sci. Mar. 54 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros E. (1990b). Structure and dynamis of the Cystoseira caespitosa Sauvegeau (Fucales phaephyceae community in the NW Mediterranean. Sci. Mar. 54 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros E., Garrabou J., Hereu B., Zabala M., Cebrian E., Sala E. (2009). Deep-water stands of Cystoseira zosteroides C. Agardh (Fucales, Ochrophyta) in the northwestern Mediterranean: insights into assemblage structure and population dynamics. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 82 477–484. 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.02.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros E., Sala E., Garrabou J., Zabala M. (1998). Community structure and frond size distribution of a deep water stand of Cystoseira spinosa Sauvageau in the Northwestern Mediterranean. Eur. J. Phycol. 33 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti-Cecchi L., Cinelli F. (1992). Effects of canopy cover, herbivores and substratum type on patterns of Cystoseira spp. settlement and recruitment in littoral rockpools. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 90 183–191. 10.3354/meps090183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti-Cecchi L., Pannacciulli F., Bulleri F., Moschella P. S., Airoldi L., Relini G., et al. (2001). Predicting the consequences of anthropogenic disturbance: large-scale effects of loss of canopy algae on rocky shores. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 214 137–150. 10.3354/meps214137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanfuné A., Boudouresque C. F., Verlaque M., Thibaut T. (2016). The fate of Cystoseira crinita, a forest-forming Fucale (Phaeophyceae, Stramenopiles), in France (North Western Mediterranean Sea). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 181 196–208. 10.1016/j.ecss.2016.08.049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolker B. M., Brooks M. E., Clark C. J., Geange S. W., Poulsen J. R., Stevens M. H. H., et al. (2009). Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24 127–135. 10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologa A. S., Sava D. (2006). Progressive decline and present trend of the romanian black sea macroalgal flora. Cercet. Mar. Rech. Mar. 36 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bray J. R., Curtis J. T. (1957). An ordination of the upland forest communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 27 325–349. 10.2307/1942268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. H., Marzinelli E. M., Vergés A., Coleman M. A., Steinberg P. D. (2014). Towards restoration of missing underwater forests. PLoS One 9:e84106. 10.1371/journal.pone.0084106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila P., Linares C., Aspillaga E., Navarro L., Kersting D., Hereu B. (2015). Recruitment patterns in the Mediterranean deep-water alga Cystoseira zosteroides. Mar. Biol. 162 1165–1174. 10.1007/s00227-015-2658-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carney L. T., Waaland J. R., Klinger T., Ewing K. (2005). Restoration of the bull kelp Nereocystis luetkeana in nearshore rocky habitats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 302 49–61. 10.3354/meps302049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman A. R. O. (1995). Functional ecology of fucoid algae: twenty-three years of progress. Phycologia 34 1–32. 10.2216/i0031-8884-34-1-1.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C. G., Serisawa Y., Ohno M., Sohn C. H. (2000). Construction of artificial seaweed beds; using the spore bag method. Algae 15 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke K. R., Gorley R. N. (2006). PRIMER v6: User Manual/Tutorial (Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research). Plymouth: PRIMER-E. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton M. N. (1992). Propagules of marine macroalgae: structure and development. Br. Phycol. J. 27 219–232. 10.1080/00071619200650231 24722520 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. A., Kelaher B. P., Steinberg P. D., Millar A. J. K. (2008). Absence of a large brown macroalga on urbanized rocky reefs around Sydney, Australia, and evidence for historical decline. J. Phycol. 44 897–901. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2008.00541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll M., Piroddi C., Steenbeek J., Kaschner K., Ben Rais Lasram F., Aguzzi J., et al. (2010). The biodiversity of the mediterranean sea: estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS One 5:e11842. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell S. D., Russell B. D., Turner D. J., Shepherd S. A., Kildea T., Miller D., et al. (2008). Recovering a lost baseline: missing kelp forests from a metropolitan coast. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 360 63–72. 10.3354/meps07526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cormaci M., Furnari G. (1999). Changes of the benthic algal flora of the Tremiti Islands (southern Adriatic ) Italy. Hydrobiologia 398 75–79. 10.1023/A:1017052332207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton P. K. (1973). Dispersion, dispersal, and persistence of the annual intertidal alga, postelsia palmaeformis ruprecht. Ecology 54 433–438. 10.2307/1934353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton P. K. (1985). Ecology of kelp communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 16 215–245. 10.1146/annurev.es.16.110185.001243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton P. K., Currie V., Gerrodette T., Keller B. D., Rick R., Ven Tresca D. (1984). Patch dynamics and stability of some california kelp communities. Ecol. Monogr. 54 253–289. 10.2307/1942498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton P. K., Tegner M. J., Parnell P. E., Edwards P. B. (1992). Temporal and spatial patterns of disturbance and recovery in a kelp forest community. Ecol. Monogr. 62 421–445. 10.2307/2937118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado O., Grau A., Pou S., Riera F., Massuti M., Zabala M., et al. (1997). Seagrass regression caused by fish cultures in Fornells Bay (Menorca, Spain). Oceanol. Acta 20 557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon S., Petraitis P. S. (2001). Scale-dependent recruitment and divergence of intertidal communities. Ecology 82 991–1006. 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0991:SDRADO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M. S. (2004). Estimating scale-dependency in disturbance impacts: El Niños and giant kelp forests in the northeast Pacific. Oecologia 138 436–447. 10.1007/s00442-003-1452-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falace A., Kaleb S., De La Fuente G., Asnaghi V., Chiantore M. (2018). Ex situ cultivation protocol for Cystoseira amentacea var. stricta (Fucales, Phaeophyceae) from a restoration perspective. PLoS One 13:e0193011. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falace A., Zanelli E., Bressan G. (2006). Algal transplantation as a potential tool for artificial reef management and environmental mitigation. Bull. Mar. Sci. 78 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen S., Sjøtun K., Lein T. E., Rueness J. (1995). Spore dispersal in laminaria hyperborea (laminariales, phaeophyceae). Sarsia 80 47–54. 10.1080/00364827.1995.10413579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giaccone G. (1973). Écologie et chorologie des Cystoseira de Méditerranée. Rapp. Com. Int. Mer Médi. 22 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gianni F., Bartolini F., Airoldi L., Ballesteros E., Francour P., Guidetti P., et al. (2013). Conservation and restoration of marine forests in the Mediterranean Sea and the potential role of marine protected areas. Adv. Oceanogr. Limnol. 4 83–101. 10.1080/19475721.2013.845604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Garreta A., Barceló M. C., Gallardo T., Perez-Ruzafa I. M., Ribera M. A., Rull J. (2002). Flora Phycologica Iberica. Fucales. 1. Murcia: Universidad deMurcia. [Google Scholar]

- Graham M. H. (2004). Effects of local deforestation on the diversity and structure of Southern California giant kelp forest food webs. Ecosystems 7 341–357. 10.1007/s10021-003-0245-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guern M. (1962). Embryologie de quelques espèces du genre Cystoseira Agardh 1821 (Fucales). Vie Milieu 13 649–679. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyo X. (1981). El Port de Maó: un ecosistema de gran interés ecològic i didàctic. Maina 3 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Irving A. D., Balata D., Colosio F., Ferrando G. A., Airoldi L. (2009). Light, sediment, temperature, and the early life-history of the habitat-forming alga Cystoseira barbata. Mar. Biol. 156 1223–1231. 10.1007/s00227-009-1164-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendrick G. A., Walker D. I. (1991). Dispersal distances for propagules of Sargassum spinuligerum (Sargassaceae, Phaeophyta) measured directly by vital staining and venturi suction sampling. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 79 133–138. 10.3354/meps079133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krumhansl K. A., Okamoto D. K., Rassweiler A., Novak M., Bolton J. J., Cavanaugh K. C., et al. (2016). Global patterns of kelp forest change over the past half-century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 13785–13790. 10.1073/pnas.1606102113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling S. D., Johnson C. R., Frusher S. D., Ridgway K. R. (2009). Overfishing reduces resilience of kelp beds to climate-driven catastrophic phase shift. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 22341–22345. 10.1073/pnas.0907529106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotze H. K., Coll M., Dunne J. A. (2011). Historical changes in marine resources, food-web structure and ecosystem functioning in the Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean. Ecosystems 14 198–222. 10.1007/s10021-010-9404-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangialajo L., Chiantore M., Cattaneo-Vietti R. (2008). Loss of fucoid algae along a gradient of urbanisation, and structure of benthic assemblages. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 358 63–74. 10.3354/meps07400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mangialajo L., Chiantore M., Susini M. L., Meinesz A., Cattaneo-Vietti R., Thibaut T. (2012). Zonation patterns and interspecific relationships of fucoids in microtidal environments. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 412 72–80. 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.10.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mann K. (1973). Seaweeds: their productivity and strategy for growth. Science 224 347–353. 10.1126/science.177.4047.410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkol-Finkel S., Ferrario F., Nicotera V., Airoldi L. (2012). Conservation challenges in urban seascapes: promoting the growth of threatened species on coastal infrastructures. J. Appl. Ecol. 49 1457–1466. 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02204.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J. C., Bates D. M. (eds) (2000). “Linear mixed-effects models: basic concepts and examples,” in Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS, (New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; ), 3–56. 10.1007/0-387-22747-4_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2016). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reed D. C., Foster M. S. (2012). The effects of canopy shadings on algal recruitment and growth in a giant Kelp forest. Ecology 65 937–948. 10.2307/1938066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed D. C., Laur D. R., Ebeling A. W. (1988). Variation in algal dispersal and recruitment: the importance of episodic events. Ecol. Monogr. 58 321–335. 10.2307/1942543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robvieux P. (2013). Conservation Des Populations de Cystoseira en Régions Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur et Corse. Nice: Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Femenías J. (1888). Algas de las Baleares. Anales Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat. 18 199–274. [Google Scholar]

- Sales M., Ballesteros E. (2009). Shallow Cystoseira (Fucales: Ochrophyta) assemblages thriving in sheltered areas from Menorca (NW Mediterranean): relationships with environmental factors and anthropogenic pressures. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 84 476–482. 10.1016/j.ecss.2009.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sales M., Ballesteros E., Anderson M. J., Ivesa L., Cardona E. (2012). Biogeographical patterns of algal communities from the Mediterranean Sea: Cystoseira crinita-dominated assemblages as a case study. J. Biogeograp. 39 140–152. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02564.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sales M., Cebrian E., Tomas F., Ballesteros E. (2011). Pollution impacts and recovery potential in three species of the genus Cystoseira (Fucales, Heterokontophyta). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 92 347–357. 10.1016/j.ecss.2011.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schiel D. R., Foster M. S. (2006). The population biology of large brown seaweeds?: ecological consequences life histories of multiphase in dynamic coastal environments. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 37 343–372. 10.2307/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.30000014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seed R., O’Connor R. J. (1981). Community organization in marine algal epifaunas. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 12 49–74. 10.1146/annurev.es.12.110181.000405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serio D., Alongi G., Catra M., Cormaci M., Furnari G. (2006). Changes in the benthic algal flora of Linosa Island (Straits of Sicily, Mediterranean Sea). Bot. Mar. 49 135–144. 10.1515/BOT.2006.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smale D. A., Wernberg T. (2013). Extreme climatic event drives range contraction of a habitat-forming species. Proc. Biol. Sci. 280:20122829. 10.1098/rspb.2012.2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal R. R., Rohlf F. J. (1995). Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Stekoll M. S., Deysher L. (1996). Recolonization and restoration of upper intertidal Fucus gardneri (Fucales, Phaeophyta) following the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Hydrobiologia 326–327, 311–312. 10.1007/BF00047824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steneck R. S., Graham M. H., Bourque B. J., Corbett D., Erlandson J. M., Estes J. A., et al. (2002). Kelp forest ecosystems: biodiversity, stability, resilience and future. Environ. Conserv. 29 436–459. 10.1017/S0376892902000322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Susini M. L., Mangialajo L., Thibaut T., Meinesz A. (2007). Development of a transplantation technique of Cystoseira amentacea var. stricta and Cystoseira compressa. Hydrobiologia 580 241–244. 10.1007/s10750-006-0449-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terawaki T., Yoshikawa K., Yoshida G., Uchimura M., Iseki K. (2003). Ecology and restoration techniques for Sargassum beds in the Seto Inland Sea, Japan. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 47 198–201. 10.1016/S0025-326X(03)00054-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut T., Blanfuné A., Boudouresque C.-F., Verlaque M. (2015). Decline and local extinction of Fucales in French Riviera: the harbinger of future extinctions? Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 16 206–224. 10.12681/mms.1683 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaut T., Pinedo S., Torras X., Ballesteros E. (2005). Long-term decline of the populations of Fucales (Cystoseira spp. and Sargassum spp.) in the Albères coast (France, North-western Mediterranean). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 50 1472–1489. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme/Mediterranean Action Plan [UNEP/MAP] (2013). Protocol Concerning Specially Protected Areas and Biological Diversity in the Mediterranean. List of Endangered Species. Athina: UNEP/MAP. [Google Scholar]

- Vadas R. L., Johnson J. S., Norton T. A. (1992). Recruitment and mortality of early post-settlement stages of benthic algae. Br. Phycol. J. 27 331–351. 10.1080/00071619200650291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valdazo J., Viera-Rodríguez M. A., Espino F., Haroun R., Tuya F. (2017). Massive decline of Cystoseira abies-marina forests in Gran Canaria Island (Canary Islands, eastern Atlantic ). Sci. Mar. 81 499–507. 10.3989/scimar.04655.23A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vergés A., Doropoulos C., Malcolm H. A., Skye M., Garcia-Pizá M., Marzinelli E. M., et al. (2016). Long-term empirical evidence of ocean warming leading to tropicalization of fish communities, increased herbivory, and loss of kelp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 13791–13796. 10.1073/pnas.1610725113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergés A., Steinberg P. D., Hay M. E., Poore A. G. B., Campbell A. H., Ballesteros E., et al. (2014). The tropicalization of temperate marine ecosystems?: climate-mediated changes in herbivory and community phase shifts. Proc. Biol. Sci. 281:20140846. 10.1098/rspb.2014.0846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernberg T., Bennett S., Babcock R. C., de Bettignies T., Cure K., Depczynski M., et al. (2016). Climate-driven regime shift of a temperate marine ecosystem. Science 353 169–172. 10.1126/science.aad8745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatsuya K. (2010). Techniques for the restoration of Sargassum beds on barren grounds. Bull. Fish Res. Agen. 32 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y. Q., Zhang Q. S., Tang Y. Z., Zhang S. B., Lu Z. C., Chu S. H., et al. (2012). Establishment of intertidal seaweed beds of Sargassum thunbergii through habitat creation and germling seeding. Ecol. Eng. 44 10–17. 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.03.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zabala M., Ballesteros E. (1989). Surface-dependent strategies and energy flux in benthic marine communites or, why corals do not exist in the Mediterranean. Sci. Mar. 53 3–17. [Google Scholar]