Abstract

Dimedone is a widely used reagent to assess the redox state of cysteine‐containing proteins as it will alkylate sulfenic acid residues, but not sulfinic acid residues. While it has been reported that dimedone can label selenenic acid residues in selenoproteins, we investigated the stability, and reversibility of this label in a model peptide system. We also wondered whether dimedone could be used to detect seleninic acid residues. We used benzenesulfinic acid, benzeneseleninic acid, and model selenocysteine‐containing peptides to investigate possible reactions with dimedone. These peptides were incubated with H2O2 in the presence of dimedone and then the reactions were followed by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC/ESI‐MS). The native peptide, H‐PTVTGCUG‐OH (corresponding to the native amino acid sequence of the C‐terminus of mammalian thioredoxin reductase), could not be alkylated by dimedone, but could be carboxymethylated with iodoacetic acid. However the “mutant peptide,” H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH, could be labeled with dimedone at low concentrations of H2O2, but the reaction was reversible by addition of thiol. Due to the reversible nature of this alkylation, we conclude that dimedone is not a good reagent for detecting selenenic acids in selenoproteins. At high concentrations of H2O2, selenium was eliminated from the peptide and a dimeric form of dimedone could be detected using LCMS and 1H NMR. The dimeric dimedone product forms as a result of a seleno‐Pummerer reaction with Sec‐seleninic acid. Overall our results show that the reaction of dimedone with oxidized cysteine residues is quite different from the same reaction with oxidized selenocysteine residues.

Keywords: sulfenic acid, sulfinic acid, selenenic acid, seleninic acid, dimedone, Pummerer reaction, selenocysteine

Abbreviations

- 5‐Npys

5‐nitro‐2‐pyridinesulfenyl protecting group

- βME

β‐mercaptoethanol

- Ala

alanine

- APCI

atmospheric‐pressure chemical ionization

- Cys

cysteine

- dimedone

5,5‐dimethylcyclohexane‐1,3‐dione

- DTNP

2,2′‐dithiobis(5‐nitropyridine)

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- Et2O

diethyl ether

- Gly

glycine

- GSH

glutathione

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HED

hydroxyethyl disulfide

- HPLC

high‐performance liquid chromatography

- LCMS

liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry

- MeSeO2H

methaneseleninic acid

- Mob

p‐methoxybenzyl protecting group

- MS

mass spectrometry

- mTrxR

mammalian thioredoxin reductase

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate‐reduced

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PhSeO2H

benzeneseleninic acid

- Sec

selenocysteine

- Sec‐

selenocysteine‐seleninic acid

- Ser

serine

- TCEP

tris(2‐carboxyethyl)phosphine

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TIS

triisopropylsilane

- TLC

thin‐layer chromatography

- Trx

thioredoxin

Introduction

Most selenoproteins characterized to date are oxidoreductases that utilize thiol/disulfide exchange reactions to catalyze specific reactions.1 In addition, many selenoproteins have been shown to have peroxidase activity. This peroxidase activity is due to the “Janus‐faced” nature of selenium2; the highly nucleophilic selenolate of selenocysteine (Sec) is readily oxidized by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to form a Sec‐selenenic acid, which is strongly electrophilic. Sec‐selenenic acid is then either rapidly reduced by resolving enzymic cysteine (Cys) residues, or by exogenous thiols like glutathione (GSH).1

Dimedone (5,5‐dimethylcyclohexane‐1,3‐dione), a small molecule 1,3‐diketone, is frequently used to detect protein sulfenic acids, as dimedone will alkylate Cys‐sulfenic acids forming a stable adduct that can be detected by mass spectrometry.3 It has also found use in labeling Sec‐selenenic acids of selenoproteins.4, 5 However, in the case of selenoprotein S, the selenenic acid could only be alkylated when a resolving Cys residue was mutated to serine (Ser), otherwise rapid formation of a selenosulfide bond prevented alkylation of the selenenic acid with dimedone.4

Mammalian thioredoxin reductase (mTrxR) is a selenoenzyme whose primary catalytic function is to reduce the oxidized form of thioredoxin (Trx), a small dithiol‐containing protein that serves to maintain cellular redox homeostasis.6 The enzyme also has weak peroxidase activity due to the presence of Sec as discussed above.7 Presumably, this peroxidase activity is due to the reaction of the Sec‐selenolate with H2O2 to form a Sec‐selenenic acid, which can then be resolved by an adjacent Cys residue to form a selenosulfide bond as shown in Figure 1(A). If the lifetime of the Sec‐selenenic acid is long enough it could theoretically be alkylated by dimedone [Fig. 1(B)], causing inhibition of the enzyme. Similar to the study done with selenoprotein S, we also were unable to use dimedone to alkylate the selenenic acid of wild type mTrxR as shown by the absence of inhibition of the enzyme in the presence of dimedone.4, 8

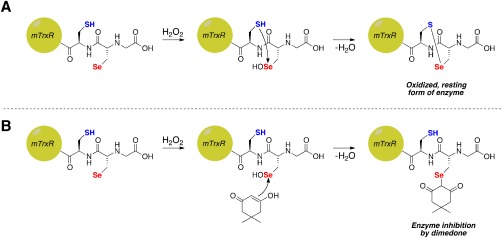

Figure 1.

Possible fates of Sec‐selenenic acid in mTrxR. (A) Oxidation of Sec in mTrxR by H2O2 to form Sec‐selenenic acid, followed by resolution by the adjacent Cys residue resulting in the formation of a selenosulfide bond and concomitant enzyme recovery from oxidation. (B) Theoretical inhibition of mTrxR by dimedone via alkylation of Sec‐selenenic acid.

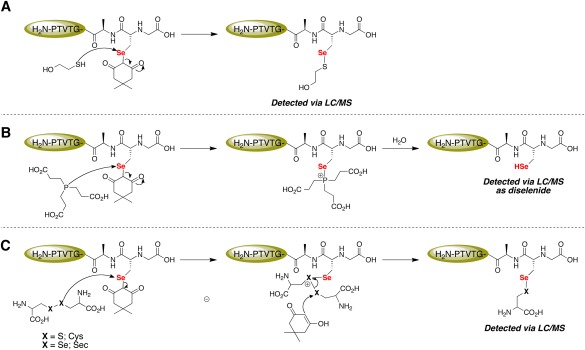

As in the case of selenoprotein S, the lack of alkylation by dimedone could be due to rapid resolution of the Sec‐selenenic acid by the adjacent, resolving Cys residue [Fig. 2(A)], but other possibilities exist as well. These other possibilities are: (i) the Sec‐selenenic acid is alkylated by dimedone, but the alkylation is rapidly reversed by the resolving Cys residue [Fig. 2(B)], and (ii) the Sec residue is over oxidized to a Sec‐seleninic acid (Sec‐ ) [Fig. 2(C)]. If the reactivity of Sec‐seleninic acid is identical to Cys‐sulfinic acid, then it is expected that dimedone would be unreactive toward Sec‐seleninic acid and alkylation would not occur. However, the reactivity of seleninic acid with dimedone is heretofore unknown

Figure 2.

Possible reasons for the absence of inhibition of thioredoxin reductase by dimedone in the presence of H2O2. (A) Rapid resolution of Sec‐selenenic acid by the adjacent Cys residue prevents alkylation. (B) Alkylation of Sec‐selenenic acid by dimedone, followed by removal of the dimedone label (pK a ∼ 5)9 by attack of the adjacent Cys residue. (C) Over oxidation of Sec to Sec‐seleninic acid, whose reactivity toward dimedone is heretofore unknown.

In this study, we explored these three options by studying the reaction of dimedone with model peptides that correspond to the C‐terminal tail of mTrxR, which contains the Sec residue. We found that the peptide H‐PTVTGCUG‐OH, containing the adjacent, resolving Cys residue, could not be alkylated with dimedone. We were, on the other hand, able to alkylate a “mutant” peptide (H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH) with dimedone in which the resolving Cys residue was replaced with alanine (Ala). However, this alkylation could be reversed by addition of reducing agents such as β‐mercaptoethanol (βME) and tris(2‐carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). Surprisingly, dimedone alkylation could also be reversed by adding disulfides such as hydroxyethyldisulfide and cystine to the alkylated peptide. The diselenide‐containing compound selenocystine also reversed dimedone alkylation.

An important finding of this study is that dimedone reacts with Sec‐seleninic acid, unlike the corresponding reaction of dimedone and Cys‐sulfinic acid. Reaction of dimedone with model seleninic acids resulted in formation of diselenides and a dimedone dimer as a result of a seleno‐Pummerer reaction.10, 11, 12, 13 We were able to detect this dimeric form of dimedone when higher concentrations of H2O2 were used to oxidize the mutant peptide, H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH, in the presence of dimedone. This result may lead to the development of a method to detect Sec‐seleninic acid, a highly transient species, in selenoproteins.

Results

Attempt to inhibit thioredoxin reductase by dimedone treatment in presence of H2O2

To address the question of whether the adjacent Cys residue of mTrxR‐GCUG interferes with alkylation of Sec‐selenenic acid by dimedone, we constructed a mutant enzyme in which the adjacent Cys residue was replaced by Gly (mTrxR‐GGUG). Both the wild type enzyme, mTrxR‐GCUG, and mutant enzyme, mTrxR‐GGUG, were subjected to a selenocystine reductase assay, which measures each enzyme's ability to reduce selenocystine after exposure to H2O2 and dimedone.14 In this assay, the % selenocystine reductase activity remaining of each enzyme after exposure to H2O2 and dimedone is indicative of how much Sec‐selenenic acid is being alkylated by dimedone. The results from this experiment are shown in Table 1. The data show that the wild type mTrxR‐GCUG enzyme retained full selenocystine reductase activity, which is identical to our previous result.8 However, the mutant mTrxR‐GGUG enzyme retained only 74% of selenocystine reductase activity after being exposed to H2O2 and dimedone. We interpret this result as the Sec‐selenenic acid of the mutant enzyme mTrxR‐GGUG being alkylated with dimedone, causing inhibition of selenocystine reductase activity. In this case, the Sec‐selenenic acid of the mutant enzyme could be alkylated because there was no resolution of Sec‐selenenic acid by the adjacent Cys residue.

Table 1.

Inhibition of wild type mammalian thioredoxin reductase (mTrxR‐GCUG) or mutant thioredoxin reductase (mTrxR‐GGUG) by dimedone treatment in presence of H2O2

| Enzyme | % Selenocystine Reductase Activity Remaining |

|---|---|

| mTrxR‐GGUG | 74 ± 1 |

| mTrxR‐GCUG | 101 ± 3 |

We believe the reason for the lack of complete inhibition of the mutant enzyme by dimedone is due to the presence of the N‐terminal redox center of the enzyme, which contains two redox active Cys residues that may be able to reverse the alkylation.

Labeling of model Sec‐containing peptides with dimedone

The peptides that we chose to synthesize were based on the C‐terminal amino acid sequence of mTrxR. We either synthesized the wild type peptide, H‐PTVTGCUG‐OH, or mutant peptide, H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH. In the case of the mutant peptide, the antepenultimate Cys residue has been mutated to Ala to avoid resolution of Sec‐selenenic acid, as would occur if the adjacent Cys was present in the peptide, resulting in the formation of a selenosulfide bond [Fig. 1(A)].

First, we performed a control experiment with the oxidized, wild type peptide. We reduced the wild type peptide with a 10‐fold excess of TCEP and subsequently alkylated it with iodoacetic acid. The results showed that both the Cys and Sec residue of the peptide could be carboxymethylated (Fig. S1 of the Supporting Information). However in a similar experiment, we were unable to alkylate the wild type peptide with either 50 μM dimedone (10‐fold excess) or 500 μM dimedone (100‐fold excess) in the presence of H2O2, identical to our results with the full‐length enzyme (Figs. S2 and S3 of the Supporting Information). The fact that we were able to dialkylate the peptide with iodoacetic acid shows that we were able to effectively reduce the selenosulfide bond with TCEP, making both the sulfur and selenium susceptible to oxidation by H2O2 and subsequent labeling by dimedone. The lack of dimedone alkylation shows that it must be the specific Se–C bond of the Sec‐dimedone adduct that is labile for the reasons we discuss in Figure 2, as the carboxymethylation of Sec by iodoacetic acid was not reversed by the resolving Cys residue.

A difficulty in our experimental design with the mutant peptide that had to be overcome was the generation of free Sec‐selenol. Alkyl selenols do not exist in solution for a long duration15 due to their tendency to oxidize to the diselenide form.16 To mitigate this problem, we utilized a strategic protecting group, 5‐Npys, on Sec, that allowed us to rapidly generate Sec‐selenol in situ, which could be further oxidized to Sec‐selenenic acid by H2O2 and alkylated with dimedone as shown in Figure 3. The selenosulfide bond between the selenium of Sec and the sulfur of the 5‐Npys group is readily cleaved by ascorbate, generating dehydroascorbic acid in the process.15 Therefore, before oxidizing the Sec peptide in the presence of dimedone, the relevant selenol form of Sec was generated by incubating the 5‐Npys‐protected Sec‐peptide with ascorbate. This approach does not depend on the use of an exogenous thiol to generate the selenol. The presence of exogenous thiol would have greatly complicated the interpretation of the results, as the added thiol could potentially reverse alkylation of Sec by dimedone.

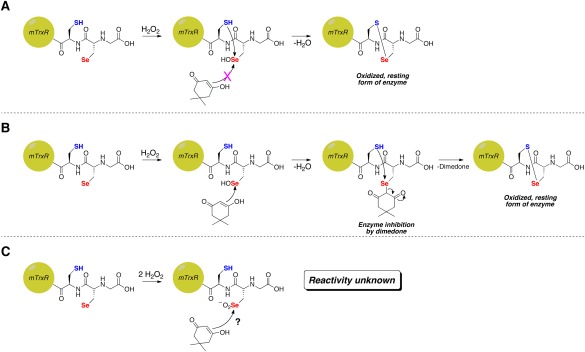

Figure 3.

Alkylation of model Sec‐containing peptide with dimedone. Sec was initially protected as Sec(5‐Npys) to prevent oxidation of the selenium atom. Ascorbate selectively removes 5‐Npys protecting group from Sec,17 generating a free Sec‐selenol, which was then oxidized by H2O2 in the presence of dimedone to alkylate the Sec‐selenenic acid.

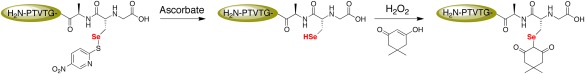

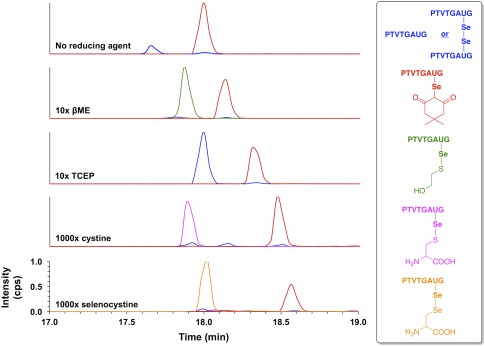

The results of our attempts to alkylate the Sec‐selenenic acid of peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH with dimedone are displayed in Figure 4. The extracted ion chromatogram in Figure 4(A) shows that the vast majority of peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH is oxidized to the Sec‐selenenic acid and subsequently alkylated with dimedone. Peptide that was not labeled was oxidized to the diselenide, which is the product of the disproportionation of two selenenic acids.16 Thus, the 10‐fold excess of dimedone relative to peptide used in the experiment was sufficient for the alkylation reaction to outcompete disproportionation. We note that, in both cases, the mass spectra shown in Figure 4(B and C) clearly display the characteristic isotope pattern of selenium‐containing peptides, which dispels any doubt that the signal corresponding to the dimedone‐alkylated H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH is artifactual.

Figure 4.

(A) Extracted ion chromatogram monitoring the elution of species with m/z values of 751.8 (blue) or 891.3 (red) after exposing peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH to alkylation conditions of 5 μM H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH, 5 μM H2O2, and 50 μM dimedone for 25 min in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. These m/z values correspond to the H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH peptide as the diselenide and dimedone‐labeled H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH peptide, respectively. It is clear that, under these alkylation conditions, the Sec‐containing peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH is oxidized to the selenenic acid and subsequently alkylated with dimedone. (B) Mass spectrum of the analyte at rt = 17.65 min. In the mass spectrum, the most intense ion is the PTVTGAUG diselenide peptide at m/z = 751.8. (C) Mass spectrum of the analyte at rt = 18.00 min. In the mass spectrum, the most intense ion is the dimedone‐labeled PTVTGAUG peptide at m/z = 891.3.

Demonstrating the lability of the Sec‐dimedone label

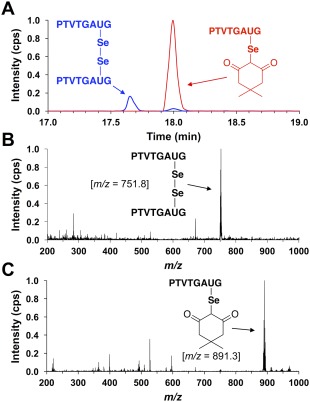

After successfully alkylating the Sec‐selenenic acid of peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH with dimedone, we desired to address the question raised in Figure 2(B), that is, could the reason why the wild type form of mTrxR retains peroxidase activity even in the presence of dimedone be due to the fact that the dimedone label is being removed by the adjacent, resolving Cys residue? To address this question, we subjected mutant peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH to the same conditions used to alkylate the Sec‐selenenic acid with dimedone, then immediately incubated the alkylated peptide with 10‐fold molar excesses of βME or TCEP for 15 min. Figure 5 shows the results from these experiments, which demonstrate that under all reducing conditions employed, the Sec‐dimedone label is labile. In the case of 10× βME, more than half of the dimedone label was removed and the peptide was detected as the βME adduct (Fig. 5). When 10× TCEP was used as the reducing agent, 50–60% of the label was also removed. The peptide was detected in the reduced form (Fig. 5), but the TCEP adduct was not detected. When 1000× βME was used, no dimedone‐labeled peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH was detected and only the βME adduct was observed (data not shown). For comparison, experiments conducted by Carroll et al. showed that the Cys‐dimedone label of a model dipeptide was stable over 12 h to similar reducing conditions of 10‐fold molar excesses of dithiothreitol (DTT), glutathione (GSH), or TCEP.17

Figure 5.

Extracted ion chromatograms monitoring the elution of species with m/z values of 751.8 and 752.8 (blue), 891.3 (red), 829.3 (green), 871.3 (magenta), and 920.2 (tangerine) after exposing dimedone‐labeled peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH to conditions of (top to bottom): no reducing agent, 10× βME, 10× TCEP, 1000× cystine, or 1000× selenocystine for 15 min in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. These m/z values correspond to peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH as the selenol (m/z 752.8), peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH as the diselenide (m/z 751.8), dimedone‐labeled peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH (m/z 891.3), the βME adduct of peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH (m/z 829.3), the cysteine adduct of peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH (m/z 871.3), and the selenocysteine adduct of peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH (m/z 920.2), respectively. The lability of the Sec‐dimedone label is demonstrated by the cases where reducing agent was added (βME and TCEP), which resulted in the amount of dimedone‐labeled H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH decreasing substantially with a corresponding increase in the amount of peptide‐βME adduct and/or peptide in the reduced, selenol form. The lability of the Sec‐dimedone label is further demonstrated by the removal of the dimedone label upon exposure to disulfide (cystine) or diselenide (selenocystine) compounds, both of which are expected to be chemically inert to alkyl selenides. Addition of cystine results in the formation of a cysteinyl‐peptide adduct, while addition of selenocystine results in the formation of a selenocysteinyl‐peptide adduct.

To further validate our experiment showing that addition of βME results in removal of the dimedone label, we did a control experiment in which hydroxyethyl disulfide was added instead. To our surprise, addition of this disulfide also resulted in removal of the dimedone label (data not shown). We then repeated this experiment using the more relevant disulfide compound cystine instead, and this disulfide also resulted in removal of the dimedone label and formation of a cysteinyl‐peptide adduct. We reasoned that addition of a diselenide should enhance removal of the dimedone label, so selenocystine was added as a removal agent. Indeed, we found that addition of the diselenide enhanced the amount of dimedone label removed from the peptide (see the bottom two panels of Fig. 5).

Reaction of dimedone with model seleninic acids

The reactivity of dimedone toward seleninic acids has not been reported in the literature so far as we are aware. While we showed that one possible reason mTrxR is not inhibited by dimedone in the presence of H2O2 is due to the removal of the Sec‐dimedone adduct by thiols [Fig. 2(B)], the question raised in Figure 2(C) still remained unaddressed, could dimedone be reacting with a Sec‐seleninic acid? We hypothesized that dimedone would react with seleninic acids because of their high Se‐electrophilicity. Seleninic acids, unlike sulfinic acids, are highly electrophilic and can be rapidly reduced by thiols and other reducing agents.2

The reactivity of dimedone toward seleninic acids was first explored in a qualitative, model experiment, where a solution of 100 mM PhSeO2H and 200 mM dimedone was prepared in methanol. After approximately 15 min, the solution turned from clear, colorless to an intense yellow color, indicating a reaction between the two compounds. The observation of this yellow color led us to hypothesize that one product of the reaction could be diphenyl diselenide, which has a yellow color in solution.

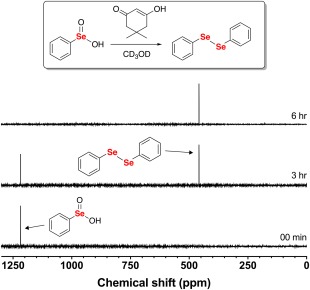

In order to further test this hypothesis, we employed a 77Se NMR time course experiment where the reaction between PhSeO2H and dimedone in CD3OD was followed for 6 h in 3 h intervals. The results from this experiment are shown in Figure 6. As shown in the figure, a resonance at δ = 463 ppm appeared within 3 h of reaction time and remained the only observable resonance after 6 h. A control 77Se NMR spectrum of the pure compound confirmed that this resonance corresponds to diphenyl diselenide, which further supports our hypothesis that dimedone is indeed reducing PhSeO2H (+2 oxidation state) to the diselenide form (−1 oxidation state). Figure S4 of the Supporting Information shows the 77Se NMR spectrum of diphenyl diselenide.

Figure 6.

77Se NMR time course of the reaction between 100 mM PhSeO2H and 200 mM dimedone in CD3OD. After 6 h of reaction time, the only observable resonance in the 77Se NMR spectrum was diphenyl diselenide.

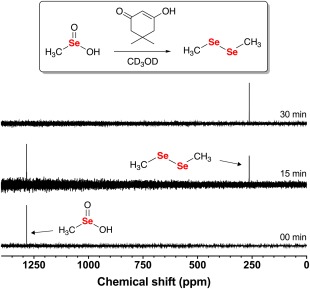

Next, in order to show that dimedone would react not only with aromatic seleninic acids, but also with alkyl seleninic acids such as Sec, we monitored the reaction of commercially available MeSeO2H with dimedone in CD3OD using the same 77Se NMR time course experiment.

As shown in Figure 7, dimedone quantitatively reduces MeSeO2H to dimethyl diselenide (δ = 263 ppm) after only 30 min of reaction time (see Fig. S5 of the Supporting Information for the control 77Se NMR spectrum of dimethyl diselenide).

Figure 7.

77Se NMR time course of the reaction between 100 mM MeSeO2H and 200 mM dimedone in CD3OD. After 30 min of reaction time, the only observable resonance in the 77Se NMR spectrum was dimethyl diselenide.

As a control, the reactivity of dimedone toward benzenesulfinic acid (PhSO2H), the sulfur‐containing analog of PhSeO2H, was explored in a 1H NMR time course experiment (see Fig. S6 of the Supporting Information). As expected, there was no observable reaction between dimedone and PhSO2H even after 7 days of reaction time. Furthermore, since PhSeO2H is a weak acid (pK a is 4.79), we conducted a control experiment designed to show that dimedone was, in fact, undergoing a redox reaction with the model seleninic acids, and not just an acid‐base reaction.18 The reactivity of dimedone in acidic media generated by p‐toluenesulfonic acid (p‐TsOH) was determined in a similar 1H NMR time course experiment and after 24 h there was no observable change in the 1H NMR spectrum (Fig. S7 of the Supporting Information), providing further evidence that dimedone is, indeed, participating in a redox reaction with the model seleninic acids.

While the identities of the selenium‐containing products of the reaction between dimedone and either PhSeO2H or MeSeO2H were readily revealed by our 77Se NMR time course experiments, the fate of dimedone in the redox reaction could not be determined by 77Se NMR. In an attempt to determine the oxidation products of dimedone in its reaction with seleninic acids, we conducted 1H NMR time course experiments monitoring the reaction between either PhSeO2H or MeSeO2H, and dimedone in CD3OD (see Figs. S8 and S9 of the Supporting Information). However, these experiments did not aid in product identification because only new alkyl 1H NMR resonances, slightly downfield of the original resonances, were observed during the time course, and these resonances were not informative.

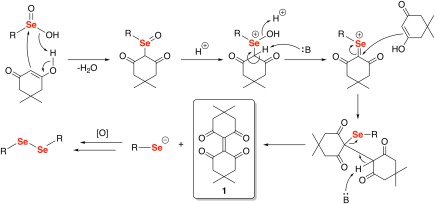

Despite this result, we hypothesized that the seleninic acids were undergoing a variation of the Pummerer reaction, as shown in Figure 8.10, 11, 12, 13 This hypothesis was based on the fact that the seleninic acid was being reduced to the diselenide, which means that dimedone must be oxidized during the reaction. In the first step of the proposed mechanism, the nucleophilic carbon atom of dimedone attacks the electrophilic selenium atom of the seleninic acid with subsequent elimination of a molecule of water, resulting in the formation of a selenoxide intermediate. After eliminating another molecule of water, the electrophilic selenonium species is attacked by another molecule of dimedone to produce a selenide. Last, elimination of selenolate anion (pK a ∼ 5.5)19 results in the formation of dimeric dimedone species 1a. The selenolate anion formed is readily oxidized to the diselenide by dissolved O2 in the buffer. The generation of 1a would coincide with the observation that new downfield alkyl resonances appeared during our 1H NMR time course experiments.

Figure 8.

Proposed mechanism of the reaction of dimedone with seleninic acids. The elimination of a selenolate anion in the second‐to‐last step of the mechanism produces the dimeric dimedone species 1a. The selenolate anion is then immediately oxidized to the diselenide by dissolved O2 to the more stable diselenide species.

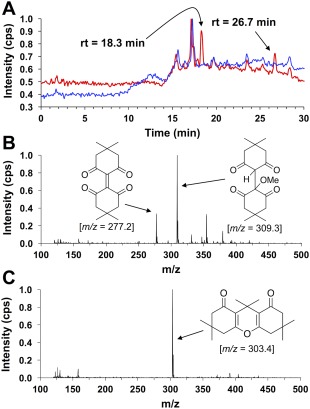

In order to verify our hypothesis that 1a is a product of our proposed seleno‐Pummerer reaction, we subjected an aliquot of the reaction between dimedone and PhSeO2H for high performance liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry (LCMS) analysis. Figure 9(A) displays the HPLC total ion current (TIC) of the reaction mixture, which shows the elution of two analytes with retention times of 18.3 min and 26.7 min, respectively. The resulting mass spectra obtained from the eluted analyte at t = 18.3 min is shown in Figure 9(B). The spectrum shows a peak at m/z = 277.2, which was identified as the [M + H]+ ion of 1a. In addition, the observation of a more intense peak at m/z = 309.3, an increase of 32 Da, supports the existence of 1a as this mass corresponds to the methanol adduct (1b). The alkene center of 1a is highly electrophilic and is unstable in nucleophilic solvents. As a result, 1a could not be isolated through employment of standard chromatographic conditions on SiO2, a result likely attributable to the highly electrophilic character of this alkene.

Figure 9.

(A) HPLC total ion current (TIC) of the reaction between 200 mM dimedone and 100 mM PhSeO2H in MeOH after 48 h of reaction time (red). The water blank is shown in blue. Two major analyte elution profiles were observed with retention times of 18.1 min and 26.5 min, respectively. (B) Mass spectrum of the analyte at t = 18.1 min in the TIC. This analyte was attributed to the dimeric dimedone species produced by the seleno‐Pummerer reaction (1a; m/z = 277.2), which exists in equilibrium with its methanol adduct (1b; m/z = 309.3) (C) Mass spectrum of the analyte at t = 26.5 min in the TIC. This analyte was attributed to the condensation product between two dimedone molecules and acetone (2; m/z = 303.4).

The mass spectrum obtained from the analyte observed at t = 26.7 min is shown in Figure 9(C). It shows only one main ion at m/z = 303.4, which we attribute to the [M + H]+ ion of the condensation product between two dimedone molecules and acetone (2).20 Acetone could be present due to either breakdown of dimedone during the reaction or contamination of the reaction glassware. Purification of 2 on SiO2 yielded 1H, 13C{1H}, and 13C‐DEPT135 NMR spectra, as well as elemental analysis data that matched the compound (see Figs. S10–S14 of the Supporting Information for characterization data of 2). One can envision a mechanism to produce 2 without direct redox interaction with the selenium atom of a seleninic acid. As 2 is the minor product of the reaction [see Fig. 9(A)], it was of little significance to this study.

The presence of 1a as a chemical signature of seleninic acid in a model peptide

Recently a molecular probe was developed to detect protein Cys‐sulfinic acids, the sulfur‐containing analog of Sec‐seleninic acids.21 However, no similar chemical probe is known to detect the presence of Sec‐seleninic acid. Our findings detailed above led us to pursue the use of 1a as a chemical footprint for the detection of Sec‐seleninic acid. We envisioned an assay in which a Sec‐containing peptide or protein would be exposed to H2O2 in the presence of dimedone. This could potentially generate a Sec‐seleninic acid in situ that could react with dimedone to produce 1a, which could then be detected by a LCMS experiment similar to the one presented in Figure 9.

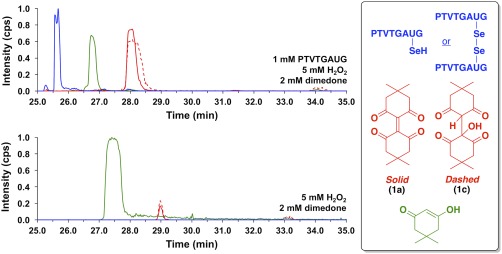

To this end, we conducted an experiment where our model Sec‐peptide, H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH, was exposed to a 5‐molar excess of H2O2 while incubated with a 2‐molar excess of dimedone. The result from this experiment is shown in the top panel of Figure 10. The extracted ion chromatogram shows that, under these conditions, 1a was produced from dimedone's reaction with the Sec‐seleninic acid of peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH. Similar to the case where methanol was the solvent, H2O adds to the electrophilic alkene center of 1a to form adduct 1c when water is the solvent (see Fig. 10). In order to demonstrate that the presence of peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH is required for the generation of 1a, we conducted a control experiment where dimedone was reacted with H2O2 alone. A small amount of 1a is present in this control experiment as shown in the bottom panel of Figure 10. However, during the course of this experiment, an unknown, contaminating selenium‐containing compound, eluted from the column (identified by the characteristic isotope pattern of selenium). This contaminant is most likely present from previous exposure of the LCMS system to selenopeptides. We hypothesized that the excess H2O2 injected into the LCMS reacted with this selenium‐containing compound to generate a seleninic acid in situ during separation on the LC column, thereby generating 1a upon its reaction with dimedone. Further control experiments using 1H NMR and direct‐infusion ESI mass spectrometry provided evidence for this claim as no reaction between dimedone and H2O2 was observed during these experiments (see Fig. S15 for 1H NMR control; see Fig. S16 for direct‐infusion ESI mass spectrometry control). Therefore, the selectivity of our proposed assay for seleninic acids is confirmed in that the generation of 1a occurs in neither the presence of H2O2 nor sulfinic acids.

Figure 10.

Extracted ion chromatograms monitoring the elution of species with m/z values of 751.8 and 752.8 (blue), 277.2 (red, solid), 295.0 (red, dashed), and 141.0 (green) after (top) the reaction of 1 mM peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH, 5 mM H2O2, and 2 mM dimedone in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 for 25 min, or (bottom) the reaction of 5 mM H2O2 and 2 mM dimedone in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 for 25 min. These m/z values correspond to peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH as the selenol (m/z 752.8), peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH as the diselenide (m/z 751.8), dimeric dimedone species 1a (m/z 277.2), the water adduct of 1 (1c; m/z 295.0), and dimedone (m/z = 141.0), respectively. The top panel demonstrates that 1a can be used as a chemical footprint for the detection of Sec‐seleninic acid under conditions of oxidative stress (5× molar excess of H2O2 in this case). The bottom panel shows a control experiment in which the Sec‐containing peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH is absent, but dimedone (2 mM) and H2O2 (5 mM) are present.

Discussion

As described in Figure 2, here we have revisited the quandary of why mTrxR cannot be inhibited by dimedone, even though a Sec‐selenenic acid, a strong electrophile, must be formed upon reaction of the enzyme with H2O2. 8 Our curiosity led us to delve into this problem based on two key observations that are described in the following two sections.

Dimedone and Sec‐selenenic acids

The first key observation came in the form of a literature search for the reported pK a value of the α‐hydrogens of dimedone, which we found to be ∼5.9 This low pK a renders dimedone a suitable leaving group in SN2‐like reactions. Further motivation was found in the form of multiple reports detailing the lability of both α‐keto sulfides and selenides toward thiols and selenols.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 The Sec‐dimedone label comprises an α‐diketo selenide, which we hypothesized would be even more labile than the reported α‐monoketo selenides. Coupled with the fact that C–Se bonds are weaker than C–S bonds due to their lower‐lying σ* orbital,29 we thought that the Sec‐dimedone bond might be labile to nucleophiles. This idea was supported by our initial experiment where we showed that the wild type mTrxR‐GCUG enzyme retained full selenocystine reductase activity in the presence of H2O2 and dimedone, whereas the mutant enzyme mTrxR‐GGUG (no resolving Cys) only retained 74% of selenocystine reductase activity under the same conditions. However, it was still unclear whether the wild type enzyme was retaining activity due to the mechanism shown in Figure 2(A) (resolution of Sec‐selenenic acid by resolving Cys) or the mechanism in Figure 2(B) (removal of dimedone label by resolving Cys).

To provide thorough evidence that the Sec‐dimedone adduct is labile and that the mechanism shown in Figure 2(B) is plausible, we turned to a peptide model to facilitate our analysis. We explicitly chose to remove the resolving Cys residue from our model wild type, peptide H‐PTVTGCUG‐OH. The reason behind this was to eliminate the possibility of selenosulfide bond formation through the mechanism shown in Figure 2(A). Reducing agents were added after the peptide was alkylated with dimedone to mimic the resolving Cys in the enzyme and the results show that, indeed, the Sec‐dimedone bond is labile.

Possible mechanisms explaining the removal of the dimedone label on H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH are shown in Figure 11. Whether βME [Fig. 11(A)], TCEP [Fig. 11(B)] or selenocystine/cystine [Fig. 11(C)] are used as removal reagents, the selenium atom of the Sec‐dimedone adduct acts as the electrophile in mechanisms similar to the one shown in Figure 2(B), except here exogenous nucleophiles are used instead of the resolving Cys residue of the peptide/enzyme. The 10‐fold excess of βME and TCEP used in this experiment is conservative when considering the theoretical effective molarity of the adjacent, resolving Cys residue in the peptide/enzyme.30, 31, 32 The surprising result that cystine (a disulfide compound) and selenocystine (a diselenide compound) were able to partially remove the Sec‐dimedone label [Fig. 11(C)] demonstrates the lability of the Sec‐dimedone adduct.

Figure 11.

Mechanistic explanation for the lability of the Sec‐dimedone label. (A) The thiol moiety of βME attacks the electrophilic Se atom of Sec and dimedone acts as the leaving group. (B) TCEP acts as the nucleophile and attacks the electrophilic Se atom of Sec and dimedone acts as the leaving group. The nascent phosphonium ion is then rapidly hydrolyzed to yield a phosphine oxide and free Sec‐selenol residue. (C) The selenium atom of Sec again acts as the electrophile and is attacked by the disulfide/diselenide moiety of either cystine or selenocystine, releasing dimedone. Dimedone, as the enol, then attacks the electrophilic sulfur/selenium atom of the cationic intermediate, resulting in the formation of a mixed selenosulfide/diselenide.

An alternative mechanism to that shown in Figure 11(C) can also be envisioned in which the selenide of the Sec‐dimedone acts as nucleophile to attack an electrophilic disulfide (cystine) or diselenide (selenocystine). The use of a selenide as a nucleophile is not unprecedented.33 Indeed, it is this characteristic of selenides that led to the development of a protecting group strategy that allows for the facile deprotection of Sec residues protected with the p‐methoxybenzyl group by our lab.34

While our data provide evidence that the mechanism shown in Figure 2(B) may explain why the wild type mTrxR‐GCUG enzyme is not inhibited by dimedone in the presence of H2O2, the data also demonstrate that dimedone may not be the most suitable molecular probe to identify Sec‐selenenic acids in proteins. In a previous report, K. S. Carroll et al. showed that the dimedone label of a Cys‐containing dipeptide was stable over 12 h when exposed to reducing conditions of 10× DTT, TCEP, or GSH in potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4.17 In a subsequent report, the authors studied the stability of linear, nucleophilic probes (designed to alkylate Cys‐sulfenic acid) to similar reducing conditions.35 Interestingly, they found that, for the most part, there was no direct correlation between leaving group potential (pK a) and stability of the Cys‐nucleophile label. The weaker C–Se bond relative to the C–S bond most likely renders the Sec‐dimedone adduct inherently labile when compared to the Cys‐dimedone adduct.

Therefore, caution must be taken when attempting to use dimedone to alkylate Sec‐selenenic acid. Any soft nucleophile, such as a thiol or phosphine, that is present during or after alkylation conditions has the ability to remove the Sec‐dimedone label as shown in Figure 11. Intracellular reducing agents such as GSH, or denaturing agents such as DTT, may cause removal of the Sec‐dimedone label during in vivo and in vitro assays, respectively, potentially leading to false negatives. Last, special attention must be paid to enzymes that possess free Cys residues near the site of Sec‐dimedone alkylation, as in the case with mTrxR and selenoprotein S. These Cys residues will interfere with Sec‐selenenic acid alkylation by either (i) reducing the Sec‐selenenic acid, resulting in a selenosulfide bond [Fig. 2(A)], or (ii) removing the dimedone label [Fig. 2(B)].

Dimedone and Sec‐seleninic acids

Our second key observation, which led us to explore dimedone's reactivity toward seleninic acids, was the realization of the explicitly opposite nature of seleninic acids when compared to sulfinic acids. Sulfinic acids are widely known as reducing agents, whereas seleninic acids are considered weak oxidizing agents.2, 36, 37, 38 The reducing (nucleophilic) property of sulfinic acids is exemplified when considering the nature of the molecular probe that was recently developed for Cys‐sulfinic acids (NO‐Bio): the probe is electrophilic and is the recipient of electrons from a Cys‐sulfinic acid.21 On the other hand, the highly oxidative (electrophilic) nature of seleninic acids allows them to be readily reduced by thiols and other, mild reducing agents such as ascorbate.2, 39, 40, 41, 42

Both PhSeO2H and MeSeO2H are inexpensive and commercially available and served us well as model compounds to investigate dimedone's reactivity toward seleninic acids. The results from our 77Se NMR time course experiments and our LCMS experiments using PhSeO2H and MeSeO2H showed that these seleninic acids were being reduced to the corresponding diselenide compounds and, as a result, were oxidizing dimedone to the dimeric form 1a in the seleno‐Pummerer reaction detailed in Figure 8.

We were initially disappointed that dimedone did not “tag” the model seleninic acids, forming a stable adduct that could be detected and used to identify a protein Sec‐seleninic acid. However, the formation of 1a led us to pursue the development of a potential assay for Sec‐seleninic acids. In the assay, 1a acts as a detectable chemical footprint indicating that a transient Sec‐seleninic acid had formed when Sec was oxidized with H2O2. We had high confidence moving forward with the development with the knowledge that both sulfinic acids and H2O2 itself are unreactive to dimedone, giving the potential assay high selectivity for Sec‐seleninic acid.

The validity of the assay was confirmed during our experiments with model peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH. In this case, the Sec‐seleninic acids were generated in situ to mimic conditions that would occur in both in vitro and in vivo assays. We were able to detect the formation of 1a via LCMS after exposing the peptide H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH to a 5‐molar excess of H2O2 and a 2‐molar excess of dimedone. A large excess of dimedone relative to peptide is not required for the formation of 1a, indicating reasonably fast reaction kinetics for assay viability. This report marks the first time a molecular probe has been used to identify the presence of a Sec‐seleninic acid.

To date, the transient seleninic acid species has been detected only by 77Se NMR,42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 X‐ray crystallography,47, 49, 50, 51 and mass spectrometry.52, 53 However, these methods of detection are not ideal. For instance, 77Se NMR is a very insensitive technique with sensitivity similar to 13C{1H} NMR, owing to its slightly higher natural abundance but lower gyromagnetic ratio relative to 13C.54 Therefore, detection of protein Sec‐seleninic acids via this method is difficult. Moreover, X‐ray crystallography is only amenable to those few Sec‐seleninic acids that are stabilized by the protein microenvironment, as in the case with selenosubtilisin and glutathione peroxidase.50, 51 Finally, detection of protein Sec‐seleninic acids by mass spectrometry is unreliable due to their high reactivity. The shortcomings of these methods to detect Sec‐seleninic acids render the potential assay we have developed, using 1a as a detectable chemical footprint, advantageous for Sec‐seleninic acid detection. Further development is currently underway in our lab to refine this assay to make it viable for in vivo detection of Sec‐seleninic acids.

Conclusions

This report has clearly demonstrated the differences in the chemical properties of Cys‐sulfenic acid and Sec‐selenenic acid toward alkylation by dimedone. A Cys‐dimedone adduct is much more stable toward nucleophiles compared to a Sec‐dimedone adduct, which is labile toward nucleophiles. The lability of the Sec‐dimedone adduct is problematic for the detection of Sec‐selenenic acids under in vivo conditions due to the presence of glutathione. Further differences between S‐oxides and Se‐oxides is demonstrated by the finding that Cys‐sulfinic acid is unreactive toward dimedone, while Sec‐seleninic acid reacts with dimedone to yield and a diselenide and a dimedone dimer, the latter forms as a result of the seleno‐Pummerer reaction. The presence of the dimedone dimer may possibly be used in the future for the detection of transient Sec‐seleninic acids in enzymes/proteins.

Materials and methods

General methods

Unless otherwise stated, all nonaqueous reactions were carried out in either oven‐dried or flame‐dried glassware. All commercially available starting materials were purchased from Aldrich, Fischer Scientific, or Acros Organics, and used as received. Analytical thin‐layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Millipore TLC Silica gel 60 F254 silica gel plates with UV indicator. Visualization was accomplished by irradiation under a 254 nm UV lamp or stained with either an aqueous solution of ceric ammonium molybdate, potassium permanganate, or phosphomolybdic acid. Flash chromatography was performed using a forced flow of the indicated solvent system on silica gel (32–63 μm particle size). Removal of solvents was accomplished on a Büchi R‐114 rotary evaporator and compounds were further dried under a high vacuum line. Elemental analysis was performed by Atlantic Microlab, Inc (Norcross, GA).

All 1H NMR data was conducted at ambient temperatures and recorded on a Varian Unity Inova (500 MHz) or Bruker ARX (500 MHz) spectrometer. 13C and 77Se NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker ARX spectrometer (125 MHz and 95 MHz, respectively). Chemical shifts for 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and 13C{1H} NMR, are reported in parts per million (ppm) at 25°C relative to chloroform or methanol (δ = 7.26 ppm or 3.31 ppm for 1H NMR; δ = 77.16 ppm or 49.00 ppm for 13C NMR, respectively). Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = pentet, br = broad, m = multiplet), coupling constants (Hz), and number of protons. Direct infusion mass spectrometry was executed using an ABI Sciex 4000QTrap Pro LCMS in positive‐ESI or APCI mode. Liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry (LCMS) was executed using an ABI Sciex 4000QTrap Pro LCMS equipped with a C18 column in positive‐ESI mode.

All analytical HPLC chromatography was carried out on a Shimadzu analytical HPLC system which utilized LC‐10AD pumps, a SPD‐10A UV‐Vis detector, and a SCL‐10A controller. A Shimadzu Shim‐pack™ VP‐ODS C18 analytical column (4.6 μm pore size, 150 × 4.6 mm) was used in these separations. Beginning with 100% Buffer A, a 1.4 mL/min gradient elution increase of 1% Buffer B/min for 50 min was used for all peptide chromatograms (Buffer A = 0.1% TFA/H2O; Buffer B = 0.1% TFA/ACN). Peptide elution profiles were detected at 214 nm and 254 nm.

Production of thioredoxin reductase by semisynthesis

The wild type mTrxR‐GCUG1 enzyme and the mutant mTrxR‐GGUG enzyme were produced by protein semisynthesis using well described methods published by our laboratory.55

Attempt to inhibit thioredoxin reductase by dimedone treatment in presence of H2O2

Wild type mTrxR‐GCUG (10 nM) or mutant mTrxR‐GGUG (50 nM), were incubated with 200 μM NADPH and 1 mM EDTA in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 for 5 min. After 5 min, 500 μM dimedone or the same volume of methanol (control) was added to the reaction mixture along with 300 μM H2O2. The reactions were incubated for 25 min followed by the addition of catalase (170 nM) for 5 min to quench the H2O2. Enzyme activity was then initiated by the addition of 90 μM selenocystine, and enzyme activity was determined spectrophotometrically by following the consumption of NADPH at 340 nm.

Peptide synthesis

Peptides were synthesized as previously described using 2‐chlorotritylchloride resin and standard Fmoc‐solid phase peptide synthesis protocol.55 Once synthesized, peptides were cleaved from the resin using a cocktail containing 96:2:2 trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), triisopropylsilane (TIS), H2O, and 2 equivalents of dithionitropyridine (DTNP).34, 56 Following cleavage, the volume was reduced by evaporation under a stream of N2 and peptide was precipitated using cold Et2O. Once dry, the peptides were suspended in H2O with minimal acetonitrile, frozen (−78°C), lyophilized, and purified via preparatory HPLC. Peptide composition was analyzed using direct infusion APCI mass spectrometry.

Labeling of model Sec‐containing peptides with dimedone

Peptides were synthesized with the Sec residue initially protected as the p‐methoxybenzyl (Mob) derivative. The Mob group on Sec was replaced with a 5‐nitro‐2‐pyridinesulfenyl (5‐Npys) group by addition of DTNP to the cleavage cocktail.56 Upon addition of DTNP, the Mob protecting group on Sec is replaced with 5‐Npys. Attack by the adjacent Cys residue of the wild type peptide (H‐PTVTGCUG‐OH) onto the selenium atom of the Sec(5‐Npys) group results in the rapid formation of an intramolecular selenosulfide bond.

The oxidized, wild type peptide (5 μM) was reduced with 50 μM tris(2‐carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0 for 15 min, followed by incubation with 50 μM or 500 μM dimedone and 5 μM H2O2 at room temperature while being shaken at low speed for 25 min. The samples were then analyzed via LCMS.

As a control, the same peptide (5 μM) was reduced with 50 μM TCEP in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 for 15 min. After, 10 mM iodoacetic acid was added and the reaction was shaken in the dark at room temperature for 25 min. The samples were then analyzed via LCMS.

In the mutant peptide, H‐PTVTGAUG‐OH, the Sec residue was protected as Sec(5‐Npys), which in this form is less reactive toward oxidation. In order to generate a free selenol in situ, the 5‐Npys protecting group was removed by addition of ascorbate in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0 for 30 min at 37°C as we have previously reported.15 The ratio of ascorbate to peptide (0.9:1) was sub‐stoichiometric to ensure that no ascorbate remained after deprotection that could potentially scavenge H2O2 or reduce oxidized Sec species during the experiment. Following deprotection, the peptide (5 μM) was incubated with 50 μM dimedone and 5 μM H2O2 at room temperature while being shaken at low speed for 25 min. The reactions were then analyzed using LCMS as described above.

Demonstrating the lability of the Sec‐dimedone label

Peptides were labeled with dimedone as described above. Following the 25 min incubation with 50 μM dimedone and 5 μM H2O2, β‐mercaptoethanol (βME, 10×), TCEP (10×), cystine (1000×), or selenocystine (1000×) were added to the reaction mixture. The reactions were incubated at room temperature for 15 min while being shaken at low speed then analyzed via LCMS.

77Se NMR time course of reactions between dimedone and seleninic acids

A concentrated solution (∼150 mM) of benzeneseleninic acid (PhSeO2H) or methaneseleninic acid (MeSeO2H) in CD3OD was made and an initial 77Se NMR spectrum was taken as the initial time point. After, the solution was diluted at room temperature with a stock solution of dimedone in CD3OD so that the final concentration of PhSeO2H or MeSeO2H was 100 mM and the concentration of dimedone was 200 mM. The solution was immediately inserted into the spectrometer and 77Se NMR spectra were taken every 3 h for 6 h (PhSeO2H) or every 15 min for 30 min (MeSeO2H).

LCMS analysis of reaction between dimedone and PhSeO2H

A 10 mL solution of 100 mM PhSeO2H and 200 mM dimedone in CH3OH was made and the reaction was allowed to proceed with stirring for 48 h at room temperature. An aliquot of the reaction mixture was taken and analyzed via LCMS as described above.

Attempt to purify dimedone byproducts of reaction between dimedone and PhSeO2H

Dimedone (280.4 mg, 2 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (10 mL) and benzeneseleninic acid (189.1 mg, 1 mmol) was added. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 48 h. The solvent was evaporated and the crude mixture was purified via flash chromatography (SiO2; 4:1 ethyl acetate/dichloromethane) to yield 2 (see Fig. 9) as a white, crystalline solid, which was the only product able to be isolated.

1H NMR (500 MHz, chloroform‐d) δ 2.28 (s, 4H), 2.22 (s, 4H), 1.63 (s, 6H), 1.06 (s, 12H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, chloroform‐d) δ 197.64, 160.58, 119.81, 53.04, 41.54, 32.16, 31.63, 28.19, 26.05. MS (pos ESI) m/z 303.4 [(M + H)+, calculated for C19H26O3: 302.41]. Anal. Calcd. for C19H26O3: C, 75.46; H, 8.67. Found: C, 74.79; H, 8.67.

Formation and detection of dimeric dimedone species upon reaction of mutant peptide and H2O2

The 5‐Npys protecting group of H‐PTVTGAU(5‐Npys)G‐OH (1 mM) was removed by incubation with ascorbate at a ratio of 0.9:1 ascorbate:peptide in 100 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0 for 30 min at 37°C as described above. Following deprotection, the peptide was incubated with 2 mM dimedone and 5 mM H2O2 for 25 min at room temperature while being shaken at low speed, after which the samples were analyzed via LCMS.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Bruce O'Rourke of the UVM Department of Chemistry for acquiring the LCMS data.

Footnote

Note: The wild type mammalian TrxR is abbreviated as mTrxR‐GCUG to indicate the amino acid composition of the last four amino acids. Likewise, mutants of mTrxR are abbreviated as mTrxR‐AA1AA2AA3AA4.

References

- 1. Hondal RJ, Marino SM, Gladyshev VN (2012) Selenocysteine in thiol/disulfide‐like exchange reactions. Antioxid Redox Signal 18:1675–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reich HJ, Hondal RJ (2016) Why nature chose selenium. ACS Chem Biol 11:821–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Klomsiri C, Nelson KJ, Bechtold E, Soito L, Johnson LC, Lowther WT, Ryu S‐E, King SB, Furdui CM, Poole LB (2010) Use of dimedone‐based chemical probes for sulfenic acid detection. Methods Enzymol 473:77–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu J, Rozovsky S (2013) Contribution of selenocysteine to the peroxidase activity of selenoprotein S. Biochemistry 52:5514–5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu J, Zhang Z, Rozovsky S (2014) Selenoprotein K form an intermolecular diselenide bond with unusually high redox potential. FEBS Lett 588:3311–3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu J, Holmgren A (2014) The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic Biol Med 66:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhong L, Holmgren A (2000) Essential role of selenium in the catalytic activities of mammalian thioredoxin reductase revealed by characterization of recombinant enzymes with selenocysteine mutations. J Biol Chem 275:18121–18128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Snider G, Grout L, Ruggles EL, Hondal RJ (2010) Methaneseleninic acid is a substrate for truncated mammalian thioredoxin reductase: implications for the catalytic mechanism and redox signaling. Biochemistry 49:10329–10338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong FM, Keeffe JR, Wu W (2002) The strength of a low‐barrier hydrogen bond in water. Tetrahedron Lett 43:3561–3564. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pummerer R (1909) Über Phenyl‐sulfoxyessigsäure. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 42:2282–2291. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pummerer R (1910) Über Phenylsulfoxy‐essigsäure (II). Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 43:1401–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hagiwara H, Kafuku K, Sakai H, Kirita M, Hoshi T, Suzuki T, Ando M (2000) Domino Michael‐seleno Pummerer type reaction (additive seleno Pummerer reaction). J Chem Soc Perkin Transs 31:2578. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith LHS, Coote SC, Sneddon HF, Procter DJ (2010) Beyond the Pummerer reaction: recent developments in thionium ion chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49:5832–5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cunniff B, Snider GW, Fredette N, Hondal RJ, Heintz NH (2013) A direct and continuous assay for the determination of thioredoxin reductase activity in cell lysates. Anal Biochem 443:34–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. SteMarie EJ, Ruggles EL, Hondal RJ (2016) Removal of the 5‐nitro‐2‐pyridine‐sulfenyl protecting group from selenocysteine and cysteine by ascorbolysis. J Pept Sci 22:571–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Besse D, Siedler F, Diercks T, Kessler H, Moroder L (1997) The redox potential of selenocystine in unconstrained cyclic peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 36:883–885. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gupta V, Carroll KS (2016) Profiling the reactivity of cyclic C‐nucleophiles towards electrophilic sulfur in cysteine sulfenic acid. Chem Sci 7:400–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McCullough JD, Gould ES (1949) The dissociation constants of some mono‐substituted benzeneseleninic acids. J Am Chem Soc 71:674–676. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Byun BJ, Kang YK (2011) Conformational preferences and pKa value of selenocysteine residue. Biopolymers 95:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Naeimi H, Nazifi ZS (2013) A highly efficient nano‐Fe3O4 encapsulated‐silica particles bearing sulfonic acid groups as a solid acid catalyst for synthesis of 1,8‐dioxo‐octahydroxanthene derivatives. J Nanoparticle Res 15:2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lo Conte M, Carroll KS (2012) Chemoselective Ligation of Sulfinic Acids with Aryl‐Nitroso Compounds. Angew Chem 124:6608–6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michinori O, Wataru F, Atsuko N (1971) The reaction of α‐carbonyl sulfides with bases. I. The reaction between α‐carbonyl sulfides with thiolates. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 44:828–832. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oki M, Funakoshi W (1971) The reaction of α‐carbonyl sulfides with bases. II. The effect of variation in the nucleophiles. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 44:832–835. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reich HJ, Renga JM, Reich IL (1975) Organoselenium chemistry. Conversion of ketones to enones by selenoxide syn elimination. J Am Chem Soc 97:5434–5447. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takahashi T, Nagashima H, Tsuji J (1978) Preparation of 1‐phenylseleno 2‐alkanones from terminal olefins and their application to organic synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett 9:799–802. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zima G, Barnum C, Liotta D (1980) Synthetic applications of 2‐phenylselenenyl enones. Selective formation of exocyclic or endocyclic enones from a common intermediate. J Organ Chem 45:2736–2737. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Makoto S, Ryo T, Isao K (1981) Oxidation of olefins into α‐phenylseleno carbonyl compounds. highly regioselective anti‐Markownikoff type oxidation of allylic alcohol derivatives. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 54:3510–3517. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arai H, Kasai M (1993) Facile nucleophilic cleavage of selenide with dimedone. Synthesis of novel 6‐demethylmitomycins. J Organ Chem 58:4151–4152. [Google Scholar]

- 29. McKillop A (2002) Main‐group metal organometallics in organic synthesis. New York: Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jacobson H, Stockmayer WH (1950) Intramolecular reaction in polycondensations. I. The theory of linear systems. J Chem Phys 18:1600–1606. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Page MI (1973) The energetics of neighbouring group participation. Chem Soc Rev 2:295–323. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kirby AJ (1980) Effective molarities for intramolecular reactions. Adv Phys Organ Chem 17:183–278. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pearson RG, Sobel HR, Songstad J (1968) Nucleophilic reactivity constants toward methyl iodide and trans‐dichlorodi (pyridine) platinum (II). J Am Chem Soc 90:319–326. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flemer S, Jr , Lacey BM, Hondal RJ (2008) Synthesis of peptide substrates for mammalian thioredoxin reductase. J Peptide Sci 14:637–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gupta V, Carroll KS (2016) Rational design of reversible and irreversible cysteine sulfenic acid‐targeted linear C‐nucleophiles. Chem Commun 52:3414–3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barton DHR, Brewster AG, Hui RAHF, Lester DJ, Ley SV, Back TG (1978) Oxidation of alcohols using benzeneseleninic anhydride. J Chem Soc Chem Commun 21:952–954. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barton DHR, Finet J‐P, Thomas M (1988) Comparative oxidation of phenols with benzeneseleninic anhydride and with benzeneseleninic acid. Tetrahedron 44:6397–6406. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reich HJ, Jasperse CP (1988) Organoselenium chemistry. Preparation and reactions of 2,4,6‐tri‐tert‐butylbenzeneselenenic acid. J Organ Chem 53:2389–2390. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kice JL, Lee TWS (1978) Oxidation‐reduction reactions of organoselenium compounds. 1. Mechanism of the reaction between seleninic acids and thiols. J Am Chem Soc 9:5094–5102. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ganther HE, Robert Lawrence J (1997) Chemical transformations of selenium in living organisms. Improved forms of selenium for cancer prevention. Tetrahedron 53:12299–12310. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ip C, Thompson HJ, Zhu Z, Ganther HE (2000) In vitro and in vivo studies of methylseleninic acid: evidence that a monomethylated selenium metabolite is critical for cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Res 60:2882–2886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Payne NC, Geissler A, Button A, Sasuclark AR, Schroll AL, Ruggles EL, Gladyshev VN, Hondal RJ (2017) Comparison of the redox chemistry of sulfur‐ and selenium‐containing analogs of uracil. Free Radic Biol Med 104:249–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. House KL, Dunlap RB, Odom JD, Wu ZP, Hilvert D (1992) Structural characterization of selenosubtilisin by selenium‐77 NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc 114:8573–8579. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sarma BK, Mugesh G (2008) Antioxidant activity of the anti‐inflammatory compound ebselen: a reversible cyclization pathway via selenenic and seleninic acid intermediates. Chemistry 14:10603–10614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bhabak KP, Vernekar AA, Jakka SR, Roy G, Mugesh G (2011) Mechanistic investigations on the efficient catalytic decomposition of peroxynitrite by ebselen analogues. Organ Biomol Chem 9:5193–5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Prabhu P, Singh BG, Noguchi M, Phadnis PP, Jain VK, Iwaoka M, Priyadarsini KI (2014) Stable selones in glutathione‐peroxidase‐like catalytic cycle of selenonicotinamide derivative. Organ Biomol Chem 12:2404–2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Singh VP, Poon J‐F, Butcher RJ, Engman L (2014) Pyridoxine‐derived organoselenium compounds with glutathione peroxidase‐like and chain‐breaking antioxidant activity. Chemistry 20:12563–12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Singh VP, Poon J‐f, Butcher RJ, Lu X, Mestres G, Ott MK, Engman L (2015) Effect of a bromo substituent on the glutathione peroxidase activity of a pyridoxine‐like diselenide. J Organ Chem 80:7385–7395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Epp O, Ladenstein R, Wendel A (1983) The refined structure of the selenoenzyme glutathione peroxidase at 0.2‐nm resolution. Eur J Biochem 133:51–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Syed R, Wu ZP, Hogle JM, Hilvert D (1993) Crystal structure of selenosubtilisin at 2.0‐.ANG. resolution. Biochemistry 32:6157–6164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ren B, Huang W, Åkesson B, Ladenstein R (1997) The crystal structure of seleno‐glutathione peroxidase from human plasma at 2.9 Å resolution. J Mol Biol 268:869–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kotrebai M, Tyson JF, Block E, Uden PC (2000) High‐performance liquid chromatography of selenium compounds utilizing perfluorinated carboxylic acid ion‐pairing agents and inductively coupled plasma and electrospray ionization mass spectrometric detection. J Chromatogr A 866:51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gammelgaard B, Cornett C, Olsen J, Bendahl L, Hansen SH (2003) Combination of LC‐ICP‐MS, LC‐MS and NMR for investigation of the oxidative degradation of selenomethionine. Talanta 59:1165–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Duddeck H (2004) 77Se NMR spectroscopy and its applications in chemistry. Annu Rep NMR Spectrosc 52:105–166. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Eckenroth B, Harris K, Turanov AA, Gladyshev VN, Raines RT, Hondal RJ (2006) Semisynthesis and characterization of mammalian thioredoxin reductase. Biochemistry 45:5158–5170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harris KM, Flemer S, Hondal RJ (2007) Studies on deprotection of cysteine and selenocysteine side‐chain protecting groups. J Pept Sci 13:81–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information