Abstract

Identifying novel therapeutic agents from natural sources and their possible intervention studies has been one of the major areas in biomedical research in recent years. Piper species are highly important - commercially, economically and medicinally. Our groups have been working for more than two decades on the identification and characterization of novel therapeutic lead molecules from Piper species. We have extensively studied the biological activities of various extracts of Piper longum and Piper galeatum, and identified and characterized novel molecules from these species. Using synthetic chemistry, various functional groups of the lead molecules were modified and structure activity relationship (SAR) studies identified synthetic molecules with better efficacy and lower IC50 values. Moreover, the mechanisms of actions of some of these molecules were studied at the molecular level. The objective of this review is to summarize experimental data published from our laboratories and others on antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potentials of Piper species and their chemical constituents.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant, Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), Endothelial cells, Piper longum, Piper galeatum

INTRODUCTION

Plants have been a great source of medicines since thousands of years. Many medicinal plants have been shown to modulate specific cellular and humoral immune functions[1]. Species of the genus Piper are among the important medicinal plants employed in various systems of medicine. Piper longum L., Piper nigrum L. and Piper galeatum L. (Piperaceae), commonly known as “long pepper”, “black pepper” and “helmet pepper” respectively, are distributed in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, throughout the Indian subcontinent, Sri Lanka, Middle Eastern countries and the Americas [2–4]. It is an important component of Indian traditional medicine reported to be used as a remedy for treating respiratory tract infection, chronic gut related pain, gonorrhea, menstrual pain, tuberculosis, and arthritic conditions [5–7].

Inflammation is the hallmark in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer and cardiovascular diseases [8]. Cell adhesion molecules play criticalroles in the recruitment and migration of inflammatory cells to the sites of inflammation [9]. Therefore, a promising therapeutic approach to diminish aberrant leukocyte adhesion isto inhibit cytokine-induced expression of cell adhesion molecules [10–12]. TNF induces free radical generation like H2O2 which activates inflammatory signaling pathways, including NF-κB in vascular cells [13–15]. An excess production or decreased scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been shown to be implicated in the pathogenesis of diverse metabolic disorders such as atherosclerosis, cancer, diabetes and neurodegeneration. Thus the antioxidant therapy has gained an importance in the treatment of such diseases linked to free radicals [16]. Normally the antioxidant property of a compound is contributed to by its (a) oxygen radical scavenging capacity, (b) the ability to inhibit cellular microsomal P-450 linked Mixed Function Oxidases (MFOs), (c) the ability to suppress the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or (d) inducing the expression of antioxidant genes like NQO1, HO1 and GCLM, etc. by activating a major transcription factor, Nrf2 [17]. In search of novel small molecules from natural sources, we have been studying the genus Piper for many years and have reported their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. We haveidentified many novel compounds from Piper species and synthesized their derivatives to study the structure activity relationships [18–20]. Herein, we have summarized the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of Piper species and their constituents from our laboratories and independent groups across the world.

BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES OF PIPER SPECIES

Inflammation is caused by live organisms or soluble antigen, and chemical or mechanical stress on tissue, which is necessary to destroy and/or dilute the injurious materials, and remove the injured tissues. It has been established that cell adhesion molecules are the key players in this process [9]. The migration of the leukocytes to the site of inflammation is regulated partly by the expression of cell adhesion molecules, viz. intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and E-selectin [15, 21]. The expression of these cell-adhesion molecules is induced on endothelial cells by various pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-1, and by bacterial LPS [22–24]. There are studies on many synthetic drugs that have been shown to inhibit the expression of these molecules but they have many side effects. Therefore, there is a need to develop a safer remedy with fewer ornegligible side effects. We have reported the effect of ethanol, chloroform and hexane extracts of P. longum and P. galeatum on TNF-α induced ICAM-1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells [2, 19, 25]. The expression of ICAM-1 was low on unstimulated endothelial cells, and itsexpression was induced over fivefold by stimulation of endothelial cells with TNF-α. It was observed that the chloroform extract of P. longum exhibits 70 % inhibition of TNF-α induced ICAM-1 expression on HUVECs, followed by hexane and ethanol extracts, which showed around 40 % inhibition [2]. The hexane and the chloroform extracts of P. galeatum showed 35 and 65 % inhibition of TNF-α induced ICAM-1 expression on endothelial cells, respectively, which is a little less than the activities of hexane and chloroform extracts of P. longum[2]. However, the inhibitory activity of ethanolic extract of P. galeatum extract is little higher than that of P. longum, it might have another active component present in it [25]. We further studied the most active P. longum’s chloroform extract (PlCE) in detail to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism accountable for inhibition of TNF-α induced ICAM-1 expression on endothelial cells. We verified its functional consequences at the cellular level and found that P.longum chloroform extract (PlCE) significantly inhibited adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial cells monolayer. This reduction is due to the ability of PlCE to block the TNF-α induced expression of cell adhesion molecules, i.e. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 at 17.5 μg/ml concentration and E-selectin at 15 μg/ml concentration on human umbilical vein endothelial cells. By performing a series of in-vitro assays, we showed that the inhibition of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin by PlCEis mediated through inhibition of Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) in endothelial cells. NF-κB is known to be one of the major transcription factors involved in the transcriptional regulation of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin expressionby inflammatory cytokines or bacterial LPS. Further, we have demonstrated the antioxidant activity of PlCE; we have shown that PlCE inhibits theNADPH-catalysed rat liver microsomal lipid peroxidation significantly [2]. These results suggest a possible mechanism of antioxidant as well as anti-inflammatory activity of PlCE. Similarly, Kumar et al. studied the antiinflammatory activity of the oil of P. longum dried fruits in rats using the carrageenan-induced right hind paw edema method [26]. The activity was compared with that of commonly used standard drug ibuprofen. The oil of P. longum dried fruits inhibited carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. The results indicated that this oil had significant (p< 0.001) anti-inflammatory activity when compared with the standard or untreated control [26]. Ghosal et al. have reported that the ethanolic extract of fruits of P. longum and piperinefrom this plant material cured 90 % and 40 % of rats with caecal amoebiasis, respectively [6, 27]. These biological activities of the extract of P. longum indicate that it has some active chemical constituents in it. Thus, we further studied the phytochemical analysis of P. longum”s extracts [19].

BIOACTIVE COMPOUNDS OF PIPER LONGUM

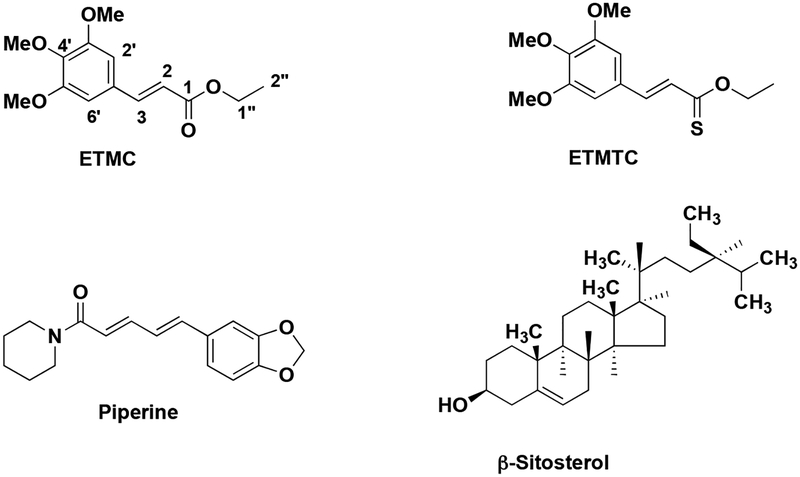

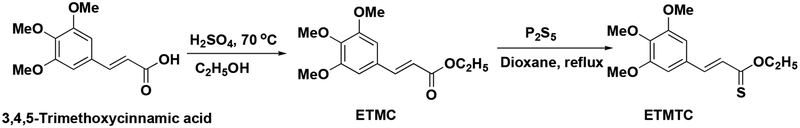

Piper longumfruit powder (100 g) was extracted with 50 % aqueous ethanol (150 mL) as described earlier [19]. The supernatant (140 mL) collected by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm was dried under vacuum and designated as “ethanolic extract”. This was treated with n-hexane (35 mL) and the hexane layer was dried and designated as “hexane fraction”. The residual material was treated with chloroform (40 mL) and the chloroform solution was designated as “chloroform extract”. The hexane and chloroform extracts of the fruits of P. longumwere pooled, as they showed almost similar spots on TLC examination. This combined extract was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using a gradient mixture of ethyl acetate and petroleum ether as the eluent; ethyl 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxycinnamate (ETMC) and piperine (Fig. 1 & Scheme 1), were eluted with 5 and 17% ethyl acetate/petroleum ether solutions, respectively. The structures of ETMCand piperinewere established on the basis of their spectral analysis (IR, 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra and HRMS) and confirmed by comparison of melting points and spectral data with those reported in the literature [19].

Fig. (1).

Structures of identified potent inhibitors of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of ETMC and ETMTC(source: Biochemistry, 2005. 44(48): p. 15944–52; Eur J Med Chem, 2011. 46(11): p. 5498–511).

ICAM-1 INHIBITION AND SAR STUDIES OF IDENTIFIED COMPOUNDS

We have tested the ability of isolated compounds in inhibiting the TNF-α induced expression of cell adhesion molecules on endothelial cells as a criterion of their anti-inflammatory activities. To elucidate their structure-function-activity relationship, we synthesized different analogues of ethyl 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxycinnamate (ETMC), and compared the ICAM-1 inhibitory activity of ETMC with those of its synthetic analogues esters (Scheme 1) as well as of the corresponding acids [19]. The pharmacological, biochemical and therapeutic properties of these cinnamates depend upon the pattern of substitution. Cinnamates have attracted wide interest in recent years due to their diverse pharmacological properties. Among these properties, their antioxidant effects have been extensively studied. The structure-activity studies indicate that the substituents in the aromatic ring, the chain length of the alcohol moietyand the presence of α,β-double bond of the cinnamic acid ester have significant effects on the inhibition of the TNF-α induced expression of ICAM-1 [19]. Previously, we have reported that substitution of oxygen with sulfur enhances the ICAM-1 inhibitory activity of coumarins [28]. To test whether substitution of oxygen with sulfur in ETMC would increase its activity, we designed and synthesized novel analogs of cinnamates, thiocinnamates and thionocinnamates and evaluated the activities of these analogs to inhibitthe TNF-α induced ICAM-1 expression on human endothelial cells. The initial screening data demonstrated that ethyl 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxythionocinnamate (ETMTC, Fig. 1 & Scheme 1) is the most potent inhibitor of TNF-α induced, VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and E-selectin expression [29]. Structure-activity relationship studies revealed the critical role of the number of methoxy groups in the aromatic ring of the cinnamoyl moiety, thechain-length of the alkyl group in the alcohol moiety and the presence of α, β- C-C double bond in the thiocinnamates and thionocinnamates. The ICAM-1 inhibitory activity data revealed that activity of the cinnamates significantly decreases with; a) an increase in the length of the alkyl chain in the alcohol part, b) a decrease in the number of methoxy groups present in the benzene ring of cinnamates, c) a decrease in the number of hydroxy groups present in the benzene ring of cinnamates. It has been observed that the dihydroxy derivatives of cinnamates were less effective in inhibiting the TNF-α induced expression of ICAM-1 than trihydroxy derivatives [19, 29–31]. After the structure-activity relationship study, we found that ethyl 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxythionocinnamate (ETMTC) is the most potent inhibitor of cell adhesion molecules, thus further preclinical and mechanstic studies were focused on ETMTC [28].

MOLECULAR MECHANISM OF THE INHIBITION OF CELL ADHESION MOLECULES

The functional consequences of inhibition of cell adhesion molecules by ETMTC at the cellular level revealed that it abrogatesthe TNF-α induced adhesion of neutrophils to the HUVEC monolayer [31]. Further, we have reported the molecular mechanism underlying the observed activity. We determined the status of NF-κB activation in ETMTC treated human endothelial cells. ETMTC was found to inhibitthe TNF-α inducednuclear translocation and activation of NF-κB by inhibiting phosphorylation and degradation ofIκBα. The inhibition of IκBα phosphorylation and degradation by ETMTC was seen to be due its ability to inhibit IκB kinase activity in endothelial cells [31].

ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY OF ETMTC

Emerging evidence indicates that reactive oxygen species contribute to diverse signaling pathways [32]. TNF-αinduced oxidative stress activates inflammatory signaling pathways, including NF-κB in vascular cells [33]. As ETMTC inhibits TNF-αinduced NF-κB activation, hence we examined the effect of ETMTC on TNF-αinduced reactive oxygen species generation in endothelial cells. We found that ETMTC significantly inhibited TNF-αinduced reactive oxygen species generation in endothelial cells. To further demonstrate its antioxidant potential, we measured the anti-oxidant gene expression in ETMTC treated bronchial epethelial cells. Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2, also known as NFE2L2 or Nrf2, is a transcription factor, which is encoded by the NFE2L2 gene in humans [34, 35]. It regulates expression of several detoxifying enzymes and is capable of protecting oxidative stress-related injury and inflammatory diseases in animals [36]. In response to antioxidants, xenobiotics, metals, and UV irradiation, Nrf2 binds strongly to antioxidant response elements (ARE) sequence and modulates ARE-mediated antioxidant enzyme gene expression [37]. Nrf2 is negatively regulated by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) and positively regulated by DJ-1 [38]. The expression of Nrf2-regulated the genes: GCLM, HO1 and NQO1 in ETMTC treated epithelial cells as analyzed by qRT-PCR as a surrogate marker of antioxidant potential and Nrf2 activation activity in ETMTC treated human epithelial cells (0.01– 20 μM). We have reported that ETMTC induces antioxidant gene expression in a concentration dependent manner and it is more potent than sulphoraphane at 10 μM concentration, further we found ETMTC to induce Nrf2-regulated anti-oxidant gene expression at protein level as confirmed by western blots [31]. ETMTC modulates the expression of Nrf2 regulators, Keap1 and DJ-1. Further, we reported that ETMTC increases the levels of NQO1-ARE mediated luciferase reporter activity. NQO1-ARE luciferase activity was determined by using stably transfected Beas-2B cells after treatment with ETMTC or SFN as positive control or DMSO as solvent [17, 18]. These findings clearly demonstrate the possible molecular mechanism of ETMTC action for inhibiting cell adhesion molecules [31].

ANTI-ASTHMATIC ACTIVITY IN PRECLINICAL MODEL

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of airways and airway epithelial injury is the hallmark of respiratory diseases and therapeutic targeting of epithelial injury has been suggested to be an effective strategy for controlling these diseases. We have clearly demonstrated that ethyl 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxythionocinnamate (ETMTC) was the most effective among various cinnamate derivatives in inhibiting inflammatory cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) expression [29, 31]. We further investigated the effects of ETMTC on the features of allergic asthma and epithelial injury in a murine model [18]. We reported that ETMTC treatment to ovalbumin sensitized and challenged mice alleviated airway hyper responsiveness, and airway inflammation. This alleviation of asthmatic features was associated with the reduction in the expressions of various CAMs, NF-κB activation, Th2 cytokines, eotaxin and 8-isoprostane [18]. It increased activities of mitochondrial complexes I and IV in lung mitochondria and reduced cytochrome c and caspase 9 activities in lung cytosol. We have also reported that it decreased the levels of oxidative DNA damage marker in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and DNA fragmentation of bronchial epithelia in lung sections. ETMTC not only increased the levels of 15-(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid but also inhibited goblet cell metaplasia and sub-epithelial fibrosis [18]. These results demonstrate that ETMTC reduces airway inflammation and thus shows its anti-inflammatory potential and could be useful in treating asthma.

BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES OF PIPERINE

Piperine (Fig. 1) is a major component of black (Piper nigrum Linn) and long (P.longum Linn) peppers, and is primarily used as a traditional food and medicine [39]. It also exhibits a variety of biological activities, which includes antioxidant, anti-pyretic and anti-tumor properties [40]. Cell adhesion molecules play a critical role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases [41, 42]. To elucidate the anti-inflammatory potential of piperine, we determined its efficacy to inhibit the TNF-α induced expression of cell adhesion molecules on endothelial cells; we found that piperine inhibited the TNF-α induced expression of cell adhesion molecules by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation in endothelial cells [20]. Further, we have reported that its ability to inhibit NF-κB activation is mediated via IκB kinase inhibition. Recently, independent groups around the globe have reported the pharmacological activities of piperine and shown that it possesses anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective, anticonvulsant, anti-ulcer and antioxidant activities, and analgesic effects [35, 43].

Angiogenesis plays an important role in tumor progression and metastasis. It is regulated by a variety of proangiogenic genes and signaling molecules including epidermal growth factor (EGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), hypoxiainducible factors, platelet-derived growth factors, angiopoetin-1 and 2, and matrix metalloproteinases [44]. Thus, inhibition of angiogenesis by down regulating pro-angiogenic factor or inducing various anti-metastatic proteins including tissue inhibitor metalloproteinases (TIMPs) could be novel therapy for cancer [45]. Piper leaf extract protects against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats [46]. Similarly, studies by Doucette et al. reported that piperine inhibits HUVEC proliferation and collagen-induced angiogenesis [47]. Piperine diminishes tumor growth and metastasis in-vitro and in-vivo model of breast cancer. It decreased PMA-induced COX-2 expression and PGE-2 production, as well as COX-2 promoter-driven luciferase activity in a dose dependent manner. Transient transfection studies utilizing COX-2 promoter deletion constructs and COX-2 promoter constructs with specific enhancer elements revealed that the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) and activator protein-1 (AP-1), were the predominant contributors to the effects of piperine. Piperine also inhibited PMA-induced NF-κB, C/EBP and c-Jun nuclear translocation [40]. Bae et al. have reported that piperine administration reduced histologic damage and myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the pancreas. It ameliorated many of the examined laboratory parameters, including the pancreatic weight (PW) to body weight (BW) ratio, as alongwith serum levels of amylase and lipase, and trypsin activity. Piperine pretreatment decreased amylase and lipase activity, cell death, and cytokine production in isolated cerulein-treated pancreatic acinar cells via inhibiting the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [48]. Oxygen radical injury and lipid peroxidation have been deemed to be major causes of atherosclerosis, cancer, liver diseases and the ageing processes [49]. Piperine possesses many anti-inflammatory properties as reported by our group and others. It has been established in in-vitro experiments that it protects against oxidative damage by quenching free radicals and reactive oxygen species and hydroxyl radicals. The effect on lipid peroxidation was also reported. Piperine at low concentrations act as a hydroxyl radical scavenger, but at higher concentrations, it activated the Fenton reaction resulting in the generation of hydroxyl radicals [50]. It acts as a powerful superoxide scavenger with IC50 of 1.82 mM and a 52 % inhibition of lipid peroxidation was observed with an IC50 of 1.23 mM. The results showed that piperine possesses direct antioxidant activity against various free radicals [50]. Piperine exhibits antioxidant activity in experimental conditions both in-vivo andin-vitroconditions through its radical quenching effect and by preventing GSH depletion.

BIOACTIVE COMPOUNDS OF P. GALEATUM

P. galeatum is native to India and grows wild in the forests of Wayanad and Kerala regions. Ten sesquiterpenes and monoterpenes have been reported to occur in the extracts of its fruits, namely β-elemene, δ-elemene, α-humulene, β-caryophyllene, α-copaene, α-ionone, 10-(acetylmethyl)-3-carene, dihydrocarvyl acetate, 1-p-menthen-8-yl acetate and linalyl acetate. We have isolated five compounds from the stems of P. galeatum, namely β-sitosterol (Fig. 1), cyclostachine-A, piperine, piperolein-B and a novel amide, viz. 1-(3’-hydroxy-5’-methoxycinnamoyl)-piperidine. The crude extracts as well as the isolated pure compounds were screened for their activity to inhibit the TNF-α induced expression of cell adhesion molecule ICAM-1. Among all, β-sitosterol was found to be the most active compound, which was taken for further studies [25].

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY ACTIVITY OF β-SITOSTEROL

Cell adhesion molecules are expressed on various immune cells and play pivotal role during any inflammatory event. Inhibition of these molecules by any pharmacological molecule is being considered as surrogative marker of the anti-inflammatory property of the molecule [42, 51, 52]. We have reported that β-sitosterol significantly inhibits the TNF-α induced expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin. Cell adhesion assay using human neutrophils has been used to measure the functional correlation of cell adhesion molecules inhibition. We have also reported that β-sitosterol significantly blocks the adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial monolayer. We investigated the status of nuclear transcription factor-κB (NF-κB) and were able to establish that β-sitosterol significantly blocks the TNF-α induced activation of NF-κB[25]. In an independent study, Loizou et al. reported similar activity of β-sitosterol in human arterial endothelial cells (HAECs) [53]. They reported that β-sitosterol inhibits significantly intracellular adhesion molecule 1 and vascular adhesion molecule 1 in TNF-α-stimulated HAEC as well as the binding of U937 cells to TNF-α-stimulated HAEC and attenuates the phosphorylation of nuclear factor-κB p65 [53]. β-Sitosterol isolated from leaves of Nyctanthe-sarbortristis Linn. (Oleaceae) has been reported to posess analgesic activity and anti-inflammatory activities. Analgesic activity has been shown by hot plate test and acetic acid-induced writhings and anti-inflammatory activity by carrageenan-induced hind paw edema method [54]. Recently Han et al. have investigated the effect of β-sitosterol in 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB)-induced AD-like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice. They reported that infiltration of inflammatory cells and the number of scratchings were clearly reduced in the β-sitosterol treated group compared with the DNFB-treated group. β-Sitosterol significantly reduced the levels of inflammation-related mRNA and protein in the AD skin lesions. It significantly reduced the levels of histamine, IgE, and interleukin-4 in the serum of DNFB-treated NC/Nga mice [55]. They further reported that the activation of mast cell-derived caspase-1 was decreased by treatment with β-sitosterol in the AD skin lesions. β-Sitosterol also significantly decreased the production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha from stimulated splenocytes, it inhibitedthe production and mRNA expression of TSLP through blocking of caspase-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB signal pathways in the stimulated HMC-1 cells [55].

ANTI-OXIDANT ACTIVITY OF β-SITOSTEROL

Uncontrolled production of reactive oxygen species contributes to the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as cancer and cardiovascular disorders. β-Sitosterol has been shown to be associated with cardiovascular protection, exerting its effect mainly through increasing the antioxidant defense system and effectively lowering the serum cholesterol levels in humans. Study results showed that β-sitosterol reverts the impairment of the glutathione/oxidized glutathione ratio induced by phorbol esters in RAW 264.7 macrophage cultures [56]. Further, it has been reported that β-sitosterol increases manganese superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase activities and decrease in the catalase activities, possibly associated with estrogen receptor (ER)-mediated phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PL3K)/glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3beta) signaling [57]. Antidiabetic and anti-oxidant potential of β-sitosterol has also been reported in streptozotocin-induced experimental hyperglycemia [58]. In another study, β-sitosterol has been reported to protect rats from 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer by preventing lipid peroxidation and improving antioxidant status. These data suggested to be associated with the increase in manganese superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase activities and the decrease in catalase activity. They further demonstrated that the effects of β-sitosterol on antioxidant enzymes depend on the estrogen/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway [58, 59]. These studies provide further support to the antioxidant potential of β-sitosterol and give new insights into the understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of β-sitosterol, and hence those of using Piper species in the diet.

CONCLUSION

This review opens new avenues for researchers to identify and characterize novel therapeutic molecules from Piper species and investigate their efficacy in preclinical animal models. The in-vitro and in-vivo studies from our group and others have clearly demonstrated the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential of P. longum and P. galeatum extracts and their constituents. Thus, these findings led us to propose that the use of Piper extracts or their constituents as dietary supplements may be useful in the prevention of many diseases like asthma, COPD, cancer and cardiovascular diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

BG received grants (NWP 0033 and BSC 0116) from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Govt. of India; VSP was supported by a grant from the EU under its Erasmus Mundus EMA-2 Program.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- AP-1

Activator protein-1

- ARE

Antioxidant response elements

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- bFGF

Basic fibroblast growth factor

- CAMs

Cell adhesion molecules

- C/EBP

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- DNFB

2,4-Dinitrofluorobenzene

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- ETMC

Ethyl 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxycinnamate

- ETMTC

Ethyl 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxythionocinnamate

- GSH

Glutathione

- GCLM

Glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit

- HO1

Hemeoxygenase 1

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- HAECs

Human arterial endothelial cells

- HUVEC

Human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells

- ICAM-1

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IL-1β

Interleukin 1 beta

- KEAP1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- IκBα

Inhibitory kappa B alpha

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- μM

Micromolar

- mM

Millimolar

- MFOS

Mixed function oxidases

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2

- NQO1

NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1

- PlCE

P. longum’s chloroform extract

- SAR

Structure activity relationship

- TIMPs

Tissue inhibitor metalloproteinases

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- TSLP

Thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- VCAM-1

Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Biography

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Duke JA Medicinal plants. Science, 1985. 229(4718): p. 1036, 1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Singh N; Kumar S; Singh P; Raj HG; Prasad AK; Parmar VS; Ghosh B Piper longum Linn. Extract inhibits TNF-alpha-induced expression of cell adhesion molecules by inhibiting NF-kappaB activation and microsomal lipid peroxidation. Phytomedicine, 2008. 15(4): p. 284–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chonpathompikunlert P; Wattanathorn J; Muchimapura S. Piperine, the main alkaloid of Thai black pepper, protects against neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment in animal model of cognitive deficit like condition of Alzheimer’s disease. Food Chem. Toxicol, 2010. 48(3): p. 798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Prasad Ashok, K.; Kumar Vineet; Arya1 Pragya; Kumar Sarvesh; Dabur Rajesh; Singh Naresh; Chhillar Anil, K.; Gainda L; Sharma; Ghosh Balaram; Wenge Jesper; Olsen Carl, E.; Parmar Virinder,S.. Investigations toward new lead compounds from medicinally important plants. Pure and Applied Chem, 2005. 77(1): p. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gounder R Kava consumption and its health effects. Pac Health Dialog, 2006. 13(2): p. 131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ghoshal S, Prasad BN, and Lakshmi V, Antiamoebic activity of Piper longum fruits against Entamoeba histolytica in vitro and in vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol, 1996. 50(3): p. 167–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Parmar VS; Jain SC; Bisht KS; Jain R; Taneja P; Jha A; Tyagi OD; Prasad AK; Wengel J; Olsen CE; Boll PM Phytochemistry of the genus piper. Phytochemistry, 1997. 46(4): P. 597–673. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rachelefsky GS, The inflammatory response in asthma. Am. Fam. Physician, 1992. 45(1): p. 153–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Osborn L, Leukocyte adhesion to endothelium in inflammation. Cell, 1990. 62(1): p. 3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kumar S; Sharma A; Madan B; Singhal V; Ghosh B Isoliquiritigenin inhibits IkappaB kinase activity and ROS generation to block TNF-alpha induced expression of cell adhesion molecules on human endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol, 2007. 73(10): p. 1602–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Weiser MR; Gibbs SAL; Hechtman HB; Issekutz PLC; Issekutz TB In Adhesion Molecules in Health and Disease. Ed. Marcel Dekker Inc: NewYork, 1997: p. p 55–86. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Krieglstein CF; Granger DN. Adhesion molecules and their role in vascular disease. Am. J. Hypertens, 2001. 14(6 Pt 2): p. 44S–54S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Jagetia GC, Radioprotective potential of plants and herbs against the effects of ionizing radiation. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr, 2007. 40(2): p. 74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mantovani A; Bussolino F; Introna M. Cytokine regulation of endothelial cell function: from molecular level to the bedside. Immunol Today, 1997. 18(5): p. 231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Marui N; Offermann MK; Swerlick R; Kunsch C; Rosen CA; Ahmad M; Alexander RW; Medford RM Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) gene transcription and expression are regulated through an antioxidant-sensitive mechanism in human vascular endothelial cells. J. Clin. Invest, 1993. 92(4): p. 1866–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Eshwarappa RS; Iyer S; Subaramaihha SR; Richard SA; Dhananjaya BL Antioxidant activities of Ficus glomerata (moraceae) leaf gall extracts. Pharmacognosy Res, 2015. 7(1): p. 114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kumar V; Kumar S; Hassan M; Wu H; Thimmulappa RK; Kumar A; Sharma SK; Parmar VS; Biswal S; Malhotra SV Novel chalcone derivatives as potent Nrf2 activators in mice and human lung epithelial cells. J. Med. Chem, 2011. 54(12): p. 4147–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kumar S; Mabalirajan U; Rehman R; Singh BK; Parmar VS; Prasad AK; Biswal S; Ghosh B A novel cinnamate derivative attenuates asthma features and reduces bronchial epithelial injury in mouse model. Int. Immunopharmacol, 2013. 15(1): p. 150–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kumar S; Arya P; Mukherjee C; Singh BK; Singh N; Parmar VS; Prasad AK; Ghosh B Novel aromatic ester from Piper longum and its analogues inhibit expression of cell adhesion molecules on endothelial cells. Biochemistry, 2005. 44(48): p. 15944–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kumar S; Singhal V; Roshan R; Sharma A; Rembhotkar GW; Ghosh B Piperine inhibits TNF-alpha induced adhesion of neutrophils to endothelial monolayer through suppression of NF-kappaB and IkappaB kinase activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol, 2007. 575(1–3): p. 177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Muller WA, Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in the inflammatory response. Lab Invest, 2002. 82(5): p. 521–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rahman I, Biswas SK, and Kirkham PA, Regulation of inflammation and redox signaling by dietary polyphenols. Biochem. Pharmacol, 2006. 72(11): p. 1439–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Springer TA, Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell, 1994. 76(2): p. 301–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Renauld JC, New insights into the role of cytokines in asthma. J. Clin. Pathol, 2001. 54(8): p. 577–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gupta P; Balwani S; Kumar S; Aggarwal N; Rossi M; Paumier S; Caruso F; Bovicelli P; Saso L; DePass AL; Prasad AK; Parmar VS; Ghosh B Beta-sitosterol among other secondary metabolites of Piper galeatum shows inhibition of TNF-alpha inducedcell adhesion molecule expression on human endothelial cells. Biochimie, 2010. 92(9): p. 1213–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kumar A; Panghal S; Mallapur SS; Kumar M; Ram V; Singh BK Antiinflammatory activity of Piper longum fruit oil. Indian J. Pharm. Sci, 2009. 71(4): p. 454–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Liu Y; Yadev VR; Aggarwal BB; Nair MG Inhibitory effects of black pepper (Piper nigrum) extracts and compounds on human tumor cell proliferation, cyclooxygenase enzymes, lipid peroxidation and nuclear transcription factor-kappa-B. Nat. Prod. Commun, 2010. 5(8): p. 1253–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kumar S; Singh BK; Kalra N; Kumar V; Kumar A; Prasad AK; Raj HG; Parmar VS; Ghosh B Novel thiocoumarins as inhibitors of TNF-alpha induced ICAM-1 expression on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and microsomal lipid peroxidation. Bioorg. Med. Chem, 2005. 13(5): p. 1605–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kumar S; Singh BK; Arya P; Malhotra S; Thimmulappa R; Prasad AK; Van der Eycken E; Olsen CE; DePass AL; Biswal S; Parmar VS; Ghosh B Novel natural product-based cinnamates and their thio and thiono analogs as potent inhibitors of cell adhesion molecules on human endothelial cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem, 2011. 46(11): p. 5498–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Parmar V; Kumar A; Prasad AK; Singh SK; Kumar N; Mukherjee S; Raj HG; Goel S; Errington W; Puar MS Synthesis of E- and Z-pyrazolylacrylonitriles and their evaluation as novel antioxidants. Bioorg. Med. Chem, 1999. 7(7): p. 1425–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kumar S; Singh BK; Prasad AK; Parmar VS; Biswal S; Ghosh B Ethyl 3’,4’,5’-trimethoxythionocinnamate modulates NF-kappaB and Nrf2 transcription factors. Eur. J. Pharmacol, 2013. 700(1–3): p. 32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Finkel T Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J. Cell. Biol, 2011. 194(1): p. 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xia F; Wang C; Jin Y; Liu Q; Meng Q; Liu K; Sun H Luteolin protects HUVECs from TNF-alpha-induced oxidative stress and inflammation via its effects on the Nox4/ROS-NF-kappaB and MAPK pathways. J. Atheroscler. Thromb, 2014. 21(8): p. 768–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chen X; Dodd G; Thomas S; Zhang X; Wasserman MA; Rovin BH; Kunsch C Activation of Nrf2/ARE pathway protects endothelial cells from oxidant injury and inhibits inflammatory gene expression. Am. J. Physiol Heart Circ. Physiol, 2006. 290(5): p. H1862–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Reddy AC and Lokesh BR, Studies on spice principles as antioxidants in the inhibition of lipid peroxidation of rat liver microsomes. Mol. Cell Biochem, 1992. 111(1–2): p. 117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Jed W.Fahey; Xavier Haristoy; Patrick M. Dolan; Thomas W. Kensler; Isabelle Scholtus; Katherine K. Stephenson; Paul Talalay; Alain Lozniewski. Sulforaphane inhibits extracellular, intracellular, and antibiotic-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori and prevents benzo[a]pyrene-induced stomach tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2002. 99(11): p. 7610–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kensler TW, Wakabayash N, and Biswal S, Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Ann. Rev. Pharma. Toxicol, 2007. 47: p. 89–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Clements CM; McNally RS; Conti BJ; Mak TW; Ting JP DJ-1, a cancer- and Parkinson’s disease-associated protein, stabilizes the antioxidant transcriptional master regulator Nrf2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2006. 103(41): p. 15091–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Srinivasan K, Black pepper and its pungent principle-piperine: A review of diverse physiological effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr, 2007. 47(8): p. 735–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kim HG; Han EH; Jang WS; Choi JH; Khanal T; Park BH; Tran TP; Chung YC; Jeong HG Piperine inhibits PMA-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression through downregulating NF-kappaB, C/EBP and AP-1 signaling pathways in murine macrophages. Food Chem. Toxicol, 2012. 50(7): p. 2342–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Baeuerle PA and Baltimore D, NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell, 1996. 87(1): p. 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Butcher EC, Leukocyte-endothelial cell recognition: three (or more) steps to specificity and diversity. Cell, 1991. 67(6): p. 1033–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ku SK, Kim JA, and Bae JS, Piperlonguminine downregulates endothelial protein C receptor shedding in vitro and in vivo. Inflammation, 37(2): p. 435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Shuman Moss LA, Jensen-Taubman S, and Stetler-Stevenson WG, Matrix metalloproteinases: changing roles in tumor progression and metastasis. Am. J. Pathol, 2012. 181(6): p. 1895–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bourboulia D; Jensen-Taubman S; Rittler MR; Han HY; Chatterjee T; Wei B. Stetler-Stevenson WG. Endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor blocks tumor growth via direct and indirect effects on tumor microenvironment. Am. J. Pathol, 2011. 179(5): p. 2589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Young SC; Wang CJ; Lin JJ; Peng PL; Hsu JL; Chou FP Protection effect of Piper betel leaf extract against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis in rats. Arch. Toxicol, 2007. 81(1): p. 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Han SS; Tompkins VS; Son DJ; Kamberos NL; Stunz LL; Halwani A; Bishop GA; Janz S Piperlongumine inhibits LMP1/MYC-dependent mouse B-lymphoma cells. 2013. 436(4): p. 660–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bae GS; Kim MS; Jeong J; Lee HY; Park KC; Koo BS; Kim BJ; Kim TH; Lee SH; Hwang SY; Shin YK; Song HJ; Park SJ Piperine ameliorates the severity of cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis by inhibiting the activation of mitogen activated protein kinases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, 2011. 410(3): p. 382–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Naito Y; Yoshikawa T; Yoshida N; Kondo M Role of oxygen radical and lipid peroxidation in indomethacin-induced gastric mucosal injury. Dig. Dis. Sci, 1998. 43(9 Suppl): p. 30S–34S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mittal R and Gupta RL, In vitro antioxidant activity of piperine. Methods Find Exp. Clin. Pharmacol, 2000. 22(5): p. 271–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Baldwin AS Jr., The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu. Rev. Immunol, 1996. 14: p. 649–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gorski A, The role of cell adhesion molecules in immunopathology. Immunol Today, 1994. 15(6): p. 251–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Loizou S; Lekakis I; Chrousos GP; Moutsatsou P Beta-sitosterol exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in human aortic endothelial cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res, 2010. 54(4): p. 551–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Nirmal SA; Pal SC; Mandal SC; Patil AN Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of beta-sitosterol isolated from Nyctanthes arbortristis leaves. Inflammopharmacology, 2012. 20(4): p. 219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Han NR, Kim HM, and Jeong HJ, The beta-sitosterol attenuates atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions through down-regulation of TSLP. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood), 2014. 239(4): p. 454–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Vivancos M and Moreno JJ, Beta-sitosterol modulates antioxidant enzyme response in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med, 2005. 39(1): p. 91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Shi C; Wu F; Zhu XC; Xu J. Incorporation of beta-sitosterol into the membrane increases resistance to oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation via estrogen receptor-mediated PI3K/GSK3beta signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 2013. 1830(3): p. 2538–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gupta R; Sharma AK; Dobhal MP; Sharma MC; Gupta RS. Antidiabetic and antioxidant potential of beta-sitosterol in streptozotocin-induced experimental hyperglycemia. J. Diabetes, 2011. 3(1): p. 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Baskar AA; Al Numair K.S.; Gabriel Paulraj M.; Alsaif MA, Muamar MA Ignacimuthu S Beta-sitosterol prevents lipid peroxidation and improves antioxidant status and histoarchitecture in rats with 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer. J. Med. Food, 2012. 15(4): p. 335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]