Abstract

One-on-one counseling can be an effective strategy to improve patient adherence to HIV treatment, however a definitive systematic review demonstrating the critical components of one-on-one counselling for HIV treatment adherence has not been conducted.

The aim of this systematic review is to examine articles with one-on-one counseling-based interventions, review their components and effectiveness in improving antiretroviral treatment adherence in HIV-infected patients.

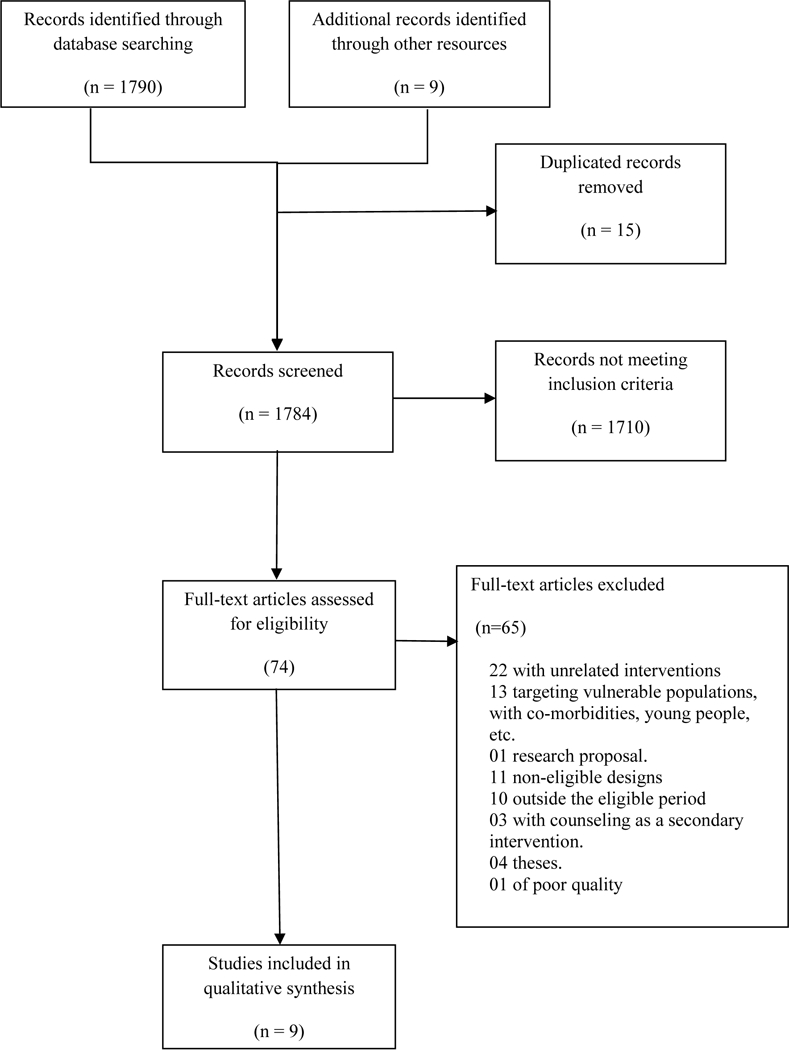

A systematic review, using the following criteria was performed: (i) experimental studies; (ii) published in Spanish, English or Portuguese; (iii) with interventions consisting primarily of counseling; (iv) adherence as the main outcome; (v) published between 2005 and 2016; (vi) targeted 18 to 60 year old, independent of gender or sexual identity. The author reviewed bibliographic databases: Literatura Peruana en Ciencias de la Salud (LIPECS), Literatura Latinoamericana en Ciencias de la Salud (LILACS), LATINDEX, Scientific Library online (Scielo), Virtual Health Library (VHL), CUIDEN, US National Library of Medicine (PubMed, PubMed Central), the Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar. Articles were analyzed according to the type of study, type of intervention, period of intervention, theoretical basis for intervention, time used in each counseling session and its outcomes.

A total of 1790 records were identified. Nine studies were selected for the review, these applied different types of individual counseling interventions and were guided by different theoretical frameworks. Counseling was applied lasting between 4 to 18 months and these were supervised through three to six sessions over the study period. Individual counseling sessions lasted from 7.5 to 90 minutes (Me. 37.5). Six studies demonstrated significant improvement in treatment.

Counseling is effective in improving adherence to ART, but methods vary. Face-to-face and computer counseling showed efficacy in improving the adherence, but not the telephone counseling. More evidence that can determine a basic counseling model without losing the individualized intervention for people with HIV is required.

Keywords: Counseling, adherence, antiretroviral therapy

Introduction

Long-term adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is key to improve and sustain quality of life amongst people living with HIV (PLWH) (Kapiamba, Masango, & Mphuthi, 2016; Kokeb & Degu, 2016; Mukherjee et al., 2014), improve the viral suppression (Viswanathan et. Al., 2015), reduce morbidity (Minkoff et. al., 2010) y mortality (Focà et. al., 2014) of patients. Adherence has been defined as “the degree to which the behavior of a person complies with adequate antiretroviral medication intake, follows the nutritional regime and changes his/her lifestyle in accordance to the health personnel recommendations” (n.d.-b, n.d.-a). Ensuring good adherence is a complex process and depends on multiple factors (Kardas et. Al., 2013), more so for chronic illnesses, such as HIV/AIDS, which require long-term polypharmacy (Günthard et al., 2016) which puts patients more at risk for poor adherence and lower likelihood of maintaining healthy lifestyle behaviors (Lam et al., 2016; n.d.-b).

Globally, scientists have developed and evaluated different interventions to improve adherence to ART. Due to the complexity of factors which cause poor adherence to ART - including individual, community, health system, and structural drivers - counseling is typically a central element of most adherence support interventions, because counseling allows the establishment of “an interpersonal, dynamic communication process, between a client and a trained counsellor, which tries to solve personal, social or psychological problems and difficulties” (UNAIDS, n.d.) in compliance with recommendations by health personnel.

In addition, the duration and intensity of counseling interventions to improve adherence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.-a; Chaiyachati et al., 2014) are important when considering drivers of effectiveness (Mills et al., 2006). Thus, counseling for health promotion focuses on providing information and acquiring healthy behaviors with minimal accompaniment, while the secondary prevention counseling, which focuses on coping with test results, learning about treatment and promoting adherence, requires more intensive intervention (Blonna & Watter, 2005). More studies are needed to determine the effects of different counseling modalities on specific outcomes (Webb, DeRubeis, & Barber, 2010).

For Kottler and Shepard, counseling is a multi-dimensional and dynamic process, where emotional, thinking, behavioral, experiential, or situational aspects from the past, present and future of a person are explored and assessed, with regards to his/her environment in a social, cultural or even economic context (Kottler & Shepard, 2014).

The success of supportive counseling interventions for treatment adherence depend on both, the immediate as well as the sustained impact on patient adherence, as patients are typically more adherent to short-term treatments for acute diseases, rather than long-term treatments for chronic illnesses as the ones required by Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection. Treatment compliance tends to drop dramatically after six months (11). In Perú, experts estimate adherence decreases over time (12). A metanalysis reported an average adherence rate greater than 90%, however actual ART adherence is 62% (Ortego et al., 2011). ART requires ≥ 95% of adherence (Harrigan et al., 2005; Paterson et al., 2000) to achieve and maintain viral suppression and prevent resistance. Several methods for measuring adherence have been developed, but the specific field of adherence measurement is still young (Berg & Arnsten, 2006). Approaches to measure adherence include: subject and provider ratings, standardized questionnaires and biochemical measurement (Chesney, 2006; Goggin et al., 2013; n.d.-b), but the use of more than one method is recommended. Some proxy methods used to indirectly assess adherence are self-reporting (Buscher, Hartman, Kallen, & Giordano, 2011), inventory of medication delivery and attendance reports (Nguyen, La Caze, & Cottrell, 2014). Some studies complement proxy adherence assessment using virologic and immunologic measurements (viral load and CD4 cell count) (McMahon et al., 2011).

A few studies based on counseling, as the main intervention, have shown success in improving ART adherence, but the duration of the effect is unknown (Cook, McCabe, Emiliozzi, & Pointer, 2009; Mugusi et al., 2009). Guidance on how, when, and for how long counseling should be applied has not been defined; and further clarity on which methods should be adapted to specific settings has not been provided.

A review from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention identified some interventions, including CARE, with promising results in improving adherence. CARE uses counseling and it is informed by the incorporation of Motivational Behavior Theory, the Transtheoretical Model, Motivational Interviewing, and Social Cognitive Theory (Prevention, n.d.).

This systematic review considered studies assessing the effectiveness of one-on-one counseling interventions to improve ART adherence in adult HIV patients, across a range of patient populations and time periods.

Methods

This systematic followed PRISMA criteria (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009; “PRISMA 2009 checklist.doc - PRISMA 2009 checklist.pdf,” n.d.)

Eligibility criteria

For the purpose of this study, we define ART counseling as an intervention where a health professional interacts with an individual patient on ART either in person or by phone, to provide education, orientation, and/or emotional support, as well as to foster patient self-efficacy (Hodgson & Spriggs, 2005) to improve their ART adherence. We selected articles using the following criteria: (i) follows an experimental study design (trial, quasi experimental and pre experimental); (ii) published in Spanish, English and Portuguese; (iii) the intervention includes counseling to improve adherence to ART; (iv) considers adherence a main study outcome; (vi) is published between 2005 and 2016; and (vii) focus in a population from 18 to 60 year old, regardless of the gender or sexual identity in low- and middle-income places and the country classification. We excluded observational studies and studies focusing on women in the perinatal period, other vulnerable populations (prisoner, illiterate, etc.), or patients who were hospitalized with other comorbidities.

Information Sources

The following databases were used to identify potential articles for inclusion: US National Library of Medicine (PubMed, PubMed Central), the Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, Literatura Peruana en Ciencias de la Salud (LIPECS), Literatura Latinoamericana en Ciencias de la Salud (LILACS), LATINDEX, Scientific Library online (Scielo), Virtual Health Library (VHL), and CUIDEN®.

Search strategy

The search strategy used the following key words joined by Boolean operator AND:

| Spanish | English | Portuguese |

|---|---|---|

| TARGA | ART | TARV |

| Consejería | Counseling | Aconselhamento |

| Adherencia | Adherence | Adesão |

The screenings from year 2005 to 2016 were used in the search.

All relevant titles from Google Scholar in Spanish were reviewed. Because of the large number of hits in Google Scholar in Portuguese and English, titles were reviewed in order of relevance, and the review stopped when 50 consecutive irrelevant articles were found.

MeSH terms used in Pubmed and Pubmed Central were “Counseling”, “Medication Adherence”, and “Antiretroviral Therapy, Highly Active”.

The search in the Cochrane Library, was made using classifier “Browse by Topic”, then using selection “infectious disease”, afterwards “HIV/AIDS” topic and finally, “adherence to treatment” as subtopics.

Study selection and data collection process

Abstracts of relevant articles were reviewed to verify that they met inclusion criteria. In some cases, it was necessary to scan the body of the article to determine eligibility. Afterwards, the full article was reviewed to assess its validity. Duplicates were identified while searching for common titles or first authors.

Data items

First, each article was reviewed twice by the same researcher to ensure fulfillment of inclusion criteria. In case there was a doubt in the evaluation, it was discussed with a second researcher to determine the inclusion of the study.

Counseling was identified in the study title and verified through the review of the abstract and aims of the study. Each article was fully reviewed to identify the type of counseling, theoretical foundation, intervention timing, number of sessions, session duration, interval between each session and if this counseling included additional components such as text messaging or reminder alarms. ART adherence was defined as the main outcome and it was assessed through more than one form of evaluation (self-report scale, electronic drug monitoring (EDM), pill counts, or through viral load or CD4 cell count determinations).

Risk of bias in individual studies

The research evaluated internal validity of published studies using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database to determine the quality of clinical trials (PEDro) (Blobaum, 2006; “Physiotherapy Evidence Database,” n.d.). According to this scale, studies of high quality have a PEDro score between 6 and 10. Studies with scores below 5 were excluded from this review.

Studies fulfilling inclusion criteria, authors, full title, type of study, type of intervention, intervention duration, theoretical basis of intervention, characteristics of intervention, time used in each counseling session, as well as outcomes and results were registered in a spreadsheet.

Data analysis

The data was organized according to subjects of study, characteristics of intervention, months of follow-up, number and duration of counseling sessions and main result over adherence.

Counseling was analyzed through content, themes or topics covered.

The statistical method for the evaluation of the intervention effect was also assessed.

Results

The studies were clinical trials with two, three or four arms. All studies applied individual counseling to improve adherence, albeit via different strategies: face to face, phone-based (Cook et al., 2009) and computer/tablet systems (de Bruin et al., 2010). The counseling models employed in these studies were guided by different theoretical frameworks including motivational, cognitive, behavioral, cognitive - behavioral, social problem-solving training, Coping and Prochaska’s transtheoretical model.

In the studies selected, counseling was applied as an intervention for several months (ranging from 4 to 18 months). The number of total sessions was different and ranging from 3 to 10 sessions (see Table 1). Each session took from 7,5 minutes to 90 minutes. In some cases, duration changed according to the type of counseling: Face to face took 30 minutes, while counseling over the phone only 7,5 min.

Table 1.

Characteristics of counseling and results from selected studies.

| Author | Subjects | Interventions | Follow-up (months) | Number and duration of counseling sessions | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chung 2011 | 79 to counseling only, | - Counseling based on model at the University of Washington HIV treatment Program. | 18 | 03 sessions | Adherence during first month among those receiving counseling higher than among those who didn’t receive it (p=0.02). Difference sustained but not significant over eighteen month (p=0.4) |

| 78 to alarm only, | 30 y 45 minutes | ||||

| 71 to counseling & alarm, | |||||

| 82 standard of care | - Small pocket digital alarm for remainders. | ||||

| Johnson, 2011 | 128 to counseling | - Counseling based on social problem solving and coping | 15 | 05 sessions | Non-adherence decreased 6% per month in the intervention group (p=0.02, OR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89 - 0.99) |

| 121 controls | 60 minutes | ||||

| Maduka 2012 | 52 to counseling and SMS | - Counseling based on cognitive intervention and SMS reminders based on behavioral intervention. | 4 | 04 sessions | The intervention group achieved better adherence than the control group (RR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.55 - 0.96) |

| 52 standard of care | 45 and 60 minutes | ||||

| Kalichman 2011 | 21 to counseling | - Behavioral self-regulation counseling delivered by cell phone. | 4 | 05 session | Improved adherence in intervention group compared with control group (p < 0.01), |

| 19 pill count training | 45 minutes approx. | ||||

| DiIorio 2008 | 125 to counseling | - Motivational interviewing (MI) individual counseling by Registered Nurses (face to face and by phone) | 12 | 05 sessions | Non-significant improvement in percent of doses taken by the intervention group. Appears better during the last months of follow up. |

| 122 standard of care | 20 and 90 minutes | ||||

| Goggin 2013 | 70 to counseling | - Motivational interviewing-based cognitive behavioral therapy (MI-CBT) counseling with modified directly observed therapy (mDOT). | 11 | 6 face-to-face and 4 telephone sessions | Non-significant improvement on adherence for the MI/mDOT group. Significant group-time interaction. |

| 69 to counseling and modified directly observed therapy (mDOT) | 25 minutes | ||||

| 65 to standard of care | |||||

| Bruin 2010 | 66 to counseling 67 controls | - Counseling. MEMS cap to monitor medication. Regular adherence counseling, use a calendar, and treatment assistant. | 9 | 30 minutes | Statistically significant effect of the intervention on timing adherence (p=0.00) |

| 67 controls | |||||

| Mugusi 2009 | 312 to counseling | 14.5 approximately | Number of sessions, not | There were no differences in adherence between the three arms (p = 0.573) | |

| 242 to counseling and calendar | specified | ||||

| 67 to treatment assistants and counseling | 5-10 minutes | ||||

| Kurth 2014 | 120 to computer counseling | - Computerized counseling | 9 | 4 session | Adherence at the follow-was higher among intervention group vs controls (p = 0.038). |

| 119 controls | |||||

Study design and data analysis procedures changed trough the studies. The number of arms ranged from 2 to 4. The methods used to determine statistical significance of differences included Chi‑square, Mann‑Whitney, U tests, t-tests, F statistic, and multilevel modelling. Outcomes were evaluated by a proportion of adherent individuals by self-report, percent of doses prescribed that are taken and number of pharmacy med caps opened per day.

Six out of nine studies showed significant improvements in adherence (self-reported, using MEMS-cap or via reduced viral load). Two out of the eight studies reported non-significant improvement in patient adherence to ART, and in only one study, the difference persisted by the end of the follow-up period (see Table 1). It is worth to mention that both studies employed motivational interviewing and the authors recognized similar limitations such as sample homogeneity (only low-income men) and intervention fidelity (medication changes over the course of the study), etc.

Although all studies reported a counseling protocol, only five out of nine studies described details and steps of their intervention. The effect of the intervention changed between studies. Chung applied the Model of Successful Antiretroviral Adherence Promotion from the University of Washington-affiliated HIV treatment program in Seattle (Chung et al., 2011). Other researchers used a novel protocol and described their pre-defined number of sessions (Johnson, Dilworth, Taylor, & Neilands, 2011; Kalichman et al., 2011; Mugusi et al., 2009).

The counseling methods from the included studies organized in differently topics from session to session, but all provided a direct link to an educational component. Two studies described the interventions content and order in detail, session by session (Chung et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2011), while the others had a brief description of their content or their steps. Most reports describe counseling without a description of contents, themes or topics, steps, timing, or other characteristics. Studies using counseling via phone neither describe contents, organization, nor priority of contents.

One study used “motivational interviewing” (MI), and another used “motivational counseling” which were defined as a collaborative conversation for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2012).

Regarding the places were studies took place, three studies were carried out in PLWH, in Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania; five studies were carried out in community or university services of the United States, one in Seattle, two in Georgia, one in San Francisco and one in Kansas; and one study was conducted in the Academic Medical Center, located in Amsterdam

Discussion

HAART Adherence is key to achieve viral suppression in PLWH (Viswanathan et. Al., 2015); it has been proved that an adherence higher than 95% gets viral suppression between the 30 and 60 days of treatment (Cheng et. al., 2018), improves the survival and well-being of patients, and it also prevents the transmission of the infection (Cluver et. Al., 2016; Minkoff et. al., 2010; Focà et. al., 2014)”. Our review suggests that one-on-one counseling is a promising strategy to promote adherence. The specific components of a successful counseling have not been evaluated extensively (Remien et al., 2006) in the literature.

Although some counseling guidelines within the reviewed studies are available (30-33), they do not systematically assess their relative efficacy (Bärnighausen et al., 2011). Researches are frequently restricted to provide information about the content of counseling sometimes, in a general manner. Usually studies do not describe in detail how the intervention could be reproduced to be effective. The studies included in this systematic review provide information about the effect of adherence counseling on outcomes for PLWH on ART, where adherence is measured directly by self-report, MEMS cap or indirectly reduction of viral load or CD4. In 2012, the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care (IAPAC) Panel (Thompson et al., 2012), issued a series of recommendations to improving adult ART adherence, which included the use of education, counseling interventions and adherence-support related tools. According to IAPAC one on one counseling interventions is effective, and thus is strongly recommended (Thompson et al., 2012). However, the criteria for the implementation to obtain the desired effect, or minimum time or conditions required to achieve the change are not specified.

According to the studies included in this review, counselors were all trained professionals who created the space for patients to discuss and explore their own difficulties or reality in order to facilitate and improved the health practices. Dilorio and Kurth, mentioned that counselors were trained for 24 hours and Bruin ensures that training can be adequately delivered in three days.

The studies showing effective counseling interventions provided a brief description of the intervention, content and results. For example, in all cases, the counseling interventions were one-on-one and explored and helped patients addressed their problems to improve adherence.

The authors applied counseling according to differing criteria, depending on their theoretical foundation. Three studies used behavioral or cognitive theories to justify their intervention design. Overall methodologies were not described in detail in any of the studies, which limits the attempts of replicability or scalability by other interested parties.

Theories applied include cognitive, behavioral, transtheoretical model, motivational interviewing and others.

It must be noted that all the interventions that offered in-person counseling had as a result, the adherence to the antiretroviral treatment, as well as the one offered by computer. Just one of the three studies that offered telephonic counseling showed efficacy in the improvement of the adherence to the treatment.

Counseling, as a clinical approach based on the patient, includes a symbolic language, role play, etc. in an environment created by the counselor. That allows the patient to express themselves freely and reflect on their attitudes and emotions to make decisions about their lives and health (Rogers, 1946). In that sense, it would be fundamental to conduct an in-person counseling with the patient. Although, the development in the telecommunications can facilitate people’s accessibility, probably they do not offer yet an atmosphere of trust and proximity that everybody requires, especially if they live in conditions of high levels stress (Lynn et. al., 2018; Spies et. al., 2018) and with the need of constant support as the PLHIV. A different reality appears with the counseling offered by computer. There is only one positive experience, but it is advisable to have more evidence about its efficacy.

According to the studies that specified the time invested in each counseling session, it can be said that the interventions with counseling sessions that lasted more than 1 hour, or less than 10 minutes were not effective in the adherence to the treatment, meanwhile, those that lasted between 30 and 60 minutes per session showed efficacy.

In terms of the time between the counseling sessions, efficacy was found in the interventions where 6 months passed between one session and another.

The interventions based on counseling in this study were, mostly, conducted in low- and middle- income settings of low, middle and high income countries according to the Words Bank classification. However, no difference was found in the efficacy of performed interventions due to the interventions based on counseling that got to be effective in adherence to treatment and that took place in low- and high-income countries. Even though there are studies that mention that the greatest amount of scientific data that shows the reduction of harmful alcohol consumption comes from high-income countries (Comité de Expertos de la OMS, 2006); there is no evidence yet that this group of countries has the greatest amount of scientific data that shows that counseling improves the adherence to TARGA.

Finally, despite that some interventions show efficacy in the first months of intervention but not in the following months; some others suggested that there are better results in a long-term process. It is not possible yet to determine the appropriate period that the intervention should last because of the lack of consistency in many intervention and methodology details; additionally, the cost of the studies also restricts this evaluation. Nevertheless, it is suggested to establish new studies that allow the evaluation of the time that counseling should last with more accuracy, as well as the need to adapt it to the part of the process in which the patient is.

In order for these findings to be consider as part of a daily professional’s practice, protocols and standard guidelines need to be defined; considering aside the individuality of each patient at the moment of applying it.

Often, researchers analyze the effectiveness results of an intervention and describe how they have been carried out with some restriction. This does not benefit professionals to accomplish replicability or adaptation of scientifically effective methodologies in similar interventions environments to achieve successful results.

Figure 1.

Selection process of studies.

Table 2.

Counseling’s Content from selected studies.

| Author | Counseling’s content |

|---|---|

| Chung 2011 | First session: explored personal barriers and taught participants about the HIV, treatment and adherence. |

| Second session: Review of a participant’s understanding and readiness to begin therapy. | |

| Third session: Examine practical and personal issues that the participant may have encountered on ART. | |

| Johnson 2011 | Session 1: Life history and HIV treatment history, HIV and General strengths and stressors, positive affect. |

| Session 2: Progress toward goal, Coping model and effectiveness training, Facilitated problem solving related to a medication stressor, exercise | |

| Session 3: Emotion vs. problem focused coping in HIV treatment, Social support skills, exercise | |

| Session 4: Identifying strengths and challenges in provider relationships, active listening and assertive communication, Facilitated problem solving related to communication with providers, exercise | |

| Session 5: Cognitive traps in coping and adherence (self-sabotaging thoughts), Cognitive facilitators in coping and adherence (self-enhancing thoughts), Barriers to adherence, Identify what has changed, Problem solve a remaining adherence barrier, Discuss how to maintain momentum | |

| Maduka 2012 | Cognitive intervention: adherence management chart for each client. |

| SMS reminders: adherence-related information and a reminder to take ART medications | |

| Kalichman 2011 | Adherence factors, behavioral skills, and affective support, medication-related beliefs and affective responses to medications can interfere with adherence. |

| DiIorio 2008 | To help participants to understand medication and taking behaviors and the actions necessary to successfully maintain a high level of adherence. |

| To encourage participants to identify and discuss barriers to adherence, to express and resolve ambivalence about taking medications and to support motivation to attain or maintain adherence. | |

| Participants discussed their medication-taking behaviors, benefits and barriers of taking medications, and ways to improve their adherence. | |

| After each medication was developed an action plan. | |

| Goggin 2013 | Techniques to increase motivation and confidence for change as well as the use of cognitive-behavioral approaches. |

| To enhance knowledge and build skills for adherence: self-monitoring, problem solving, talking to your doctor. | |

| Bruin 2010 | Adherence concepts and correct misconceptions. Then, patients select a desired yet feasible adherence level using MEMSreports. In case suboptimal level, the reasons for and consequences thereof were discussed, with the objective to increase patient’s desired status. Patients’ own MEMS-reports were printed. |

| The HIV-nurse and patient identified the causes of the non-adherent events visible in the MEMS-reports, its solutions. | |

| Finally, patients were asked about self-monitor their medication intake during the upcoming period to identify challenging situations, and give solutions. During the next intervention visit, patients’ difficulties and efforts were discussed, and new action plans are adapted. | |

| Mugusi 2009 | Causes of non-adherence in each individual patient. |

| Kurth 2014 | Audio-narrated assessment, tailored feedback, skill-building videos, health plan, and printout. |

| Information-motivation-behavior: ‘importance’ and confidence’ scales around ART use and transmission risk-reduction. | |

| Transtheoretical: stage of change questions around condoms. | |

| Social cognitive: role-modeling with peers demonstrating healthy behaviors in videos. | |

| Motivational interviewing: messages acknowledging ambivalence around behavior change and highlighting user’s commitment | |

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW009763 (Program for Advanced Research Capacities for AIDS in Peru (PARACAS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References:

- Bärnighausen T, Chaiyachati K, Chimbindi N, Peoples A, Haberer J, & Newell M-L (2011). Interventions to increase antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evaluation studies. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, 11(12), 942–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70181-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazán-Ruiz S, Pinedo C, E L, & Maguiña Vargas C (2013). Adherencia al TARGA en VIH /SIDA: Un Problema de Salud Pública. Acta Médica Peruana, 30(2), 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, & Arnsten JH (2006). Practical and Conceptual Challenges in Measuring Antiretroviral Adherence. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 43(Suppl 1), S79–S87. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qai.0000248337.97814.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobaum P (2006). Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Journal of the Medical Library Association, 94(4), 477–478. [Google Scholar]

- Blonna R, & Watter D (2005). Health Counseling: A Microskills Approach. Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Buscher A, Hartman C, Kallen MA, & Giordano TP (2011). Validity of self-report measures in assessing antiretroviral adherence of newly diagnosed, HAART-naïve, HIV patients. HIV Clinical Trials, 12(5), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1310/hct1205-244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-a). Complete List of Medication Adherence Evidence-based Behavioral Interventions [gov]. Retrieved January 16, 2017 from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/ma/complete.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-b). counselormanual.pdf. Retrieved July 14, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/counselormanual.pdf

- Chaiyachati KH, Ogbuoji O, Price M, Suthar AB, Negussie EK, & Bärnighausen T (2014). Interventions to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a rapid systematic review. AIDS (London, England), 28 Suppl 2, S187–204. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Sauer B, Zhang Y, Nickman NA, Jamjian C, Stevens V, & LaFleur J (2018). Adherence and virologic outcomes among treatment-naïve veteran patients with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Medicine, 97(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA (2006). The elusive gold standard. Future perspectives for HIV adherence assessment and intervention. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 43 Suppl 1, S149–155. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qai.0000243112.91293.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MH, Richardson BA, Tapia K, Benki-Nugent S, Kiarie JN, Simoni JM, … John-Stewart GC (2011). A randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of counseling and alarm device on HAART adherence and virologic outcomes. PLoS Medicine, 8(3), e1000422 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver LD, Toska E, Orkin FM, Meinck F, Hodes R, Yakubovich AR, & Sherr L (2016). Achieving equity in HIV-treatment outcomes: can social protection improve adolescent ART-adherence in South Africa?. AIDS care, 28(sup2), 73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comité de Expertos de la OMS en Problemas Relacionados con el Consumo de Alcohol Segundo Informe - Serie de Informes Técnicos 944 Ginebra: WHO; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Cook PF, McCabe MM, Emiliozzi S, & Pointer L (2009). Telephone nurse counseling improves HIV medication adherence: an effectiveness study. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC, 20(4), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin M, Hospers HJ, van Breukelen GJP, Kok G, Koevoets WM, & Prins JM (2010). Electronic monitoring-based counseling to enhance adherence among HIV-infected patients: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 29(4), 421–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, McCarty F, Resnicow K, McDonnell Holstad M, Soet J, Yeager K, … Lundberg B (2008). Using motivational interviewing to promote adherence to antiretroviral medications: a randomized controlled study. AIDS Care, 20(3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120701593489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focà E, Odolini S, Sulis G, Calza S, Pietra V, Rodari P, … & Pignatelli S (2014). Clinical and immunological outcomes according to adherence to first-line HAART in a urban and rural cohort of HIV-infected patients in Burkina Faso, West Africa. BMC infectious diseases, 14(1), 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goggin K, Gerkovich MM, Williams KB, Banderas JW, Catley D, Berkley-Patton J, … Clough LA (2013). A randomized controlled trial examining the efficacy of motivational counseling with observed therapy for antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS and Behavior, 17(6), 1992–2001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0467-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günthard HF, Saag MS, Benson CA, del Rio C, Eron JJ, Gallant JE, … Volberding PA (2016). Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2016 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA, 316(2), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan PR, Hogg RS, Dong WWY, Yip B, Wynhoven B, Woodward J, … Montaner JSG (2005). Predictors of HIV drug-resistance mutations in a large antiretroviral-naive cohort initiating triple antiretroviral therapy. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 191(3), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1086/427192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson J, & Spriggs M (2005). A practical account of autonomy: why genetic counseling is especially well suited to the facilitation of informed autonomous decision making. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 14(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-005-4067-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MO, Dilworth SE, Taylor JM, & Neilands TB (2011). Improving coping skills for self-management of treatment side effects can reduce antiretroviral medication nonadherence among people living with HIV. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 41(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9230-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, Swetzes C, Amaral CM, White D, … Eaton L (2011). Brief behavioral self-regulation counseling for HIV treatment adherence delivered by cell phone: an initial test of concept trial. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25(5), 303–310. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2010.0367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapiamba G, Masango T, & Mphuthi D (2016). Antiretroviral adherence and virological outcomes in HIV-positive patients in Ugu district, KwaZulu-Natal province. African Journal of AIDS Research: AJAR, 15(3), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2016.1170710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardas P, Lewek P, & Matyjaszczyk M (2013). Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Frontiers in pharmacology, 4, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokeb M, & Degu G (2016). Immunological Response of Hiv-Infected Children to Highly Active Antiretoviral Therapy at Gondar University Hospital, North-Western Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences, 26(1), 25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottler JA, & Shepard DS (2014). Introduction to Counseling: Voices from the Field. Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Lam Y, Westergaard R, Kirk G, Ahmadi A, Genz A, Keruly J, … Surkan PJ (2016). Provider-Level and Other Health Systems Factors Influencing Engagement in HIV Care: A Qualitative Study of a Vulnerable Population. PloS One, 11(7), e0158759 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn C, Bradley-Klug K, Chenneville TA, Walsh ASJ, Dedrick R, & Rodriguez C (2018). Mental health screening in integrated care settings: Identifying rates of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress among youth with HIV. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services, 1–7.30034300 [Google Scholar]

- Maduka O, & Tobin-West CI (2013). Adherence counseling and reminder text messages improve uptake of antiretroviral therapy in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice, 16(3), 302–308. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.113451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon JH, Jordan MR, Kelley K, Bertagnolio S, Hong SY, Wanke CA, … Elliott JH (2011). Pharmacy adherence measures to assess adherence to antiretroviral therapy: review of the literature and implications for treatment monitoring. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 52(4), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciq167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2012). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, … Cooper C (2006). Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Medicine, 3(11), e438 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud. (n.d.-a). Norma Técnica para la Adherencia al Tratamiento Antiretroviral de Gran Actividad - TARGA - en adultos Infectados por el Virus de la Inmunodeficiencia Humana. Retrieved December 19, 2016, from www.unfpa.org.pe/Legislacion/PDF/20120717-MINSA-NT-Atencion-Adulto-VIH.pdf

- Minkoff H, Zhong Y, Burk RD, Palefsky JM, Xue X, Watts DH, … & Massad, LS (2010). Influence of Adherent and Effective Antiretroviral Therapy Use on Human Papillomavirus Infection and Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions in Human Immunodeficiency Virus—Positive Women. The Journal of infectious diseases, 201(5), 681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, & Group TP (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugusi F, Mugusi S, Bakari M, Hejdemann B, Josiah R, Janabi M, … Sandstrom E (2009). Enhancing adherence to antiretroviral therapy at the HIV clinic in resource constrained countries; the Tanzanian experience. Tropical Medicine & International Health: TM & IH, 14(10), 1226–1232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02359.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Shah N, Singh R, Vajpayee M, Kabra SK, & Lodha R (2014). Outcome of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected Indian children. BMC Infectious Diseases, 14, 701 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0701-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T-M-U, La Caze A, & Cottrell N (2014). What are validated self-report adherence scales really measuring?: a systematic review. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 77(3), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortego C, Huedo-Medina TB, Llorca J, Sevilla L, Santos P, Rodríguez E, … Vejo J (2011). Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): a meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 15(7), 1381–1396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-9942-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg L, & Blaschke T (2005). Adherence to medication. The New England Journal of Medicine, 353(5), 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, … Singh N (2000). Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 133(1), 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physiotherapy Evidence Database,. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2017, from https://www.pedro.org.au/

- Prevention, C. for D. C. and. (n.d.). CARE+ - cdc-hiv-care_ma_good.pdf. Retrieved July 20, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research/interventionresearch/compendium/ma/cdc-hiv-care_ma_good.pdf

- PRISMA 2009. checklist.doc - PRISMA 2009 checklist.pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA%202009%20checklist.pdf

- Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Dognin J, Day E, El-Bassel N, & Warne P (2006). Moving From Theory to Research to Practice: Implementing an Effective Dyadic Intervention to Improve Antiretroviral Adherence for Clinic Patients. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 43(Supplement 1), S69–S78. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qai.0000248340.20685.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR (1946). Significant aspects of client-centered therapy. American Psychologist, 1(10), 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies G, Konkiewitz EC, & Seedat S (2018). Incidence and Persistence of Depression Among Women Living with and Without HIV in South Africa: A Longitudinal Study. AIDS and Behavior, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, … Nachega JB (2012). Guidelines for Improving Entry Into and Retention in Care and Antiretroviral Adherence for Persons With HIV: Evidence-Based Recommendations From an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel. Annals of Internal Medicine, 156(11), 817 https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. (n.d.). UNAIDS Terminology Guidelines - 2015_terminology_guidelines_en.pdf. Retrieved October 4, 2017, from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2015_terminology_guidelines_en.pdf

- Vega A, Maddaleno M, & Mazin R. (n.d.). YCC_span_fin.indd-sa-youth.pdf. Retrieved July 14, 2017, from http://www1.paho.org/spanish/ad/fch/ca/sa-youth.pdf

- Viswanathan S, Justice AC, Alexander GC, Brown TT, Gandhi NR, McNicholl IR, … & Jacobson LP (2015). Adherence and HIV RNA suppression in the current Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART). Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 69(4), 493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb CA, DeRubeis RJ, & Barber JP (2010). Therapist Adherence/Competence and Treatment Outcome: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (n.d.-b). Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Retrieved December 19, 2016, from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf

- World Health Organization. (n.d.-a). Basic Counselling Guidelines for Anti-retroviral (ARV) Therapy Programmes - 9241593067_eng.pdf. Retrieved July 14, 2017, from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43196/1/9241593067_eng.pdf

- World Health Organization,. (n.d.-b). Counselling for maternal and newborn health care: a handbook for building skills. Retrieved July 14, 2017, from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44016/1/9789241547628_eng.pdf?ua=1 [PubMed]