Abstract

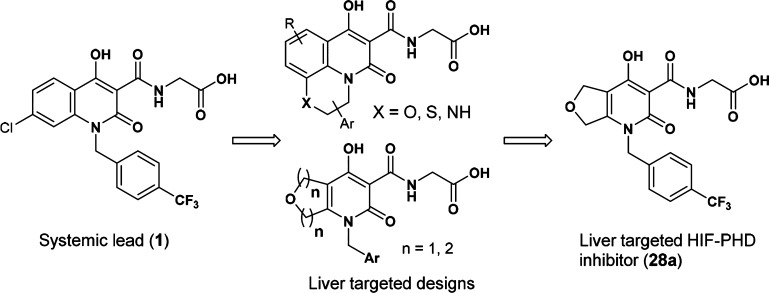

We report herein the design and synthesis of a series of orally active, liver-targeted hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase (HIF-PHD) inhibitors for the treatment of anemia. In order to mitigate the concerns for potential systemic side effects, we pursued liver-targeted HIF-PHD inhibitors relying on uptake via organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs). Starting from a systemic HIF-PHD inhibitor (1), medicinal chemistry efforts directed toward reducing permeability and, at the same time, maintaining oral absorption led to the synthesis of an array of structurally diverse hydroxypyridone analogues. Compound 28a was chosen for further profiling, because of its excellent in vitro profile and liver selectivity. This compound significantly increased hemoglobin levels in rats, following chronic QD oral administration, and displayed selectivity over systemic effects.

Keywords: Anemia, HIF-PHD inhibitors, EPO, hydroxypyridone, OATP, permeability, liver selective

Anemia is a disease condition where patients have lower than normal hemoglobin (Hb) levels in the blood, usually <12 g Hb/dL.1 Anemic patients experience fatigue, shortness of breath, and diminished functional status, and therefore endure a suboptimal quality of life. The common causes of anemia include a range of medical conditions, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD),2 chemotherapy-induced anemia (CIA),3 and anemia of chronic disease (ACD).4,5 Currently, the standard of care for anemia seeks to enhance patient functionality and quality of life by restoring effective red blood cell (RBC) production through parenteral administration of recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO).6 Despite significant advantages over RBC transfusions, the treatment of anemia with EPO analogues suffers from many shortcomings, including inconvenience, EPO resistance, and most importantly, safety concerns. It has been known that rhEPO treatment may contribute to adverse cardiovascular outcomes.7 Therefore, the industry has continued efforts toward new treatments for anemia.

Accumulating evidence has suggested that hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase (HIF-PHD) inhibitors act as hypoxia mimetics by stabilizing the transcription factor HIF, which modulates numerous genes, including those involved in erythropoiesis and iron handling.8 Proof-of-concept for the treatment of anemia in patients with CKD has been achieved for this mechanism with Fibrogen’s small molecule HIF-PHD inhibitors FG-22169 and FG-4592.10 To date, at least six small-molecule HIF-PHD inhibitors have been tested in humans for treating renal disease-associated anemia.11−13 Recently, we also disclosed two structurally diverse HIF-PHD inhibitors.14,15 To our knowledge, all of these compounds are systemic, nontissue selective HIF-PHD inhibitors. Given the complex pharmacology of HIF stabilization and its broad tissue expression,16 systemic HIF-PHD inhibition may have pleiotropic effects. In order to mitigate the potential risk for undesired systemic effects, we pursued a liver-targeted HIF-PHD inhibitor.17 Herein, we report our efforts toward this end.

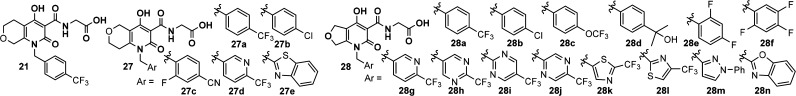

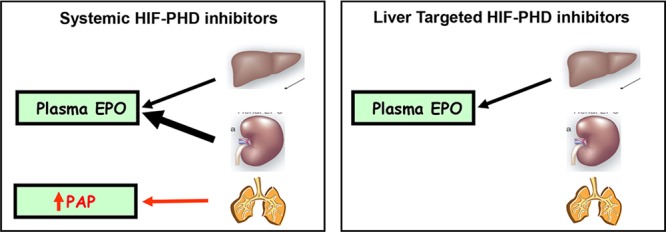

During fetal development, the liver is the primary organ producing EPO; post-natally, EPO is mainly produced by the kidneys and, to a lesser extent, by the liver.18 Then, through systemic circulation, EPO reaches the bone marrow, where it binds to the EPO receptor, stimulating erythropoiesis. We hypothesized that liver-selective HIF-PHD inhibition would “re-activate” hepatic EPO production, triggering sufficient RBC generation to ameliorate anemia, while avoiding potential systemic side effects, such as pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) increase (see Figure 1).19 Indeed, Minamishima and Kaelin have shown that liver-selective deletion of PHD1/2/3 in mice resulted in increased serum EPO levels that paralleled the mRNA levels in liver and exceeded those achieved by renal PHD2 knockout.20 Consistent with the hypothesis, liver-selective knockdown with PHD2 siRNA in rhesus led to clinically relevant increases in hemoglobin.21 In addition, we have demonstrated that a systemic HIF-PHD inhibitor (HIF-PHDi) had increased systolic PAP (sPAP) in a dose-dependent manner in a telemetered rat model (see Figure 2).22

Figure 1.

Hypothesis: effects of HIF-PHD inhibition—systemic versus liver-targeted.

Figure 2.

Systolic PAP increase with systemic HIF-PHDi FG-2216 in PAP telemetry rats.

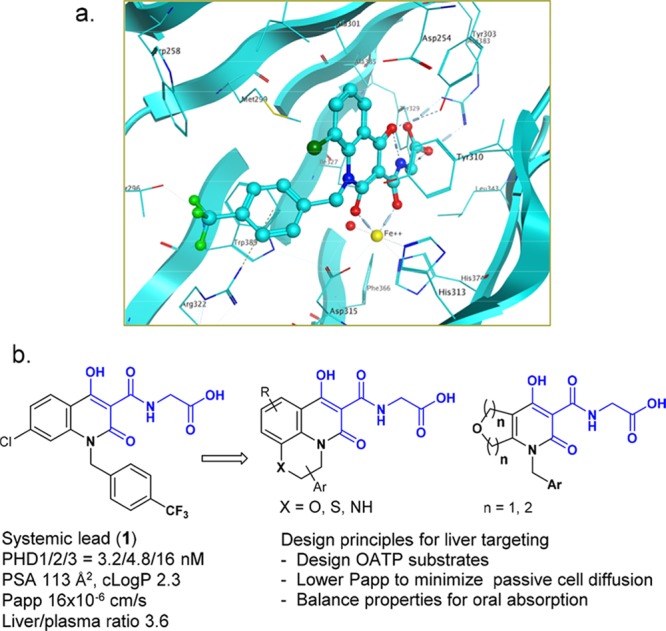

With this supporting evidence in mind, we undertook a discovery effort to identify a hepatoselective HIF-PHD inhibitor. There existed several approaches for liver targeting, for example, utilization of liver-specific transport proteins,23 HepDirect Cytochrome P450-activated prodrugs,24 and nanoparticles to deliver incorporated therapeutic agents.25 We decided to design substrates for active transport relying on organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs)23 to achieve hepatoselectivity, and strategically envisioned meeting this objective through modification of a systemic lead (1).26 Specifically, we sought to keep the critical structural features (highlighted in blue in Figure 3) intact to maintain key interactions with Fe2+, Tyr303, and Arg383 of the enzyme, and study the SAR of the other parts of the molecule, following the design principles outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

a) X-ray co-crystal structure of a PHD2 domain with Cl regioisomer of 1; (b) from systemic lead to hepatoselective designs.

Our SAR studies focused on optimizing liver selectivity and balancing properties to achieve acceptable oral absorption. Our goal was to increase liver selectivity by engaging active transport into hepatocytes via the liver specific OATPs, and by simultaneously decreasing the extent of passive cell permeability. Acidic moieties can serve as key transporting elements to enable recognition by the OATP transport proteins. Our strategy was to take advantage of the carboxylic acid group present in the systemic lead and design away from passive transport.

There are three isoforms of PHD, namely, PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3, and inactivation of all the three isoforms leads to optimal erythrocytosis.12 We aimed to develop a pan-PHD inhibitor. After assessment of compounds in assays for PHD catalytic activity, compounds of interest were selected for passive permeability (Papp) evaluation. Compounds with low permeability (Papp < 10 × 10–6 cm/s) were further evaluated in rat tissue PK, where the distribution ratio of liver versus plasma was obtained.22

Passive permeability is closely related to molecular properties such as lipophilicity (LogP)27 and polar surface area (PSA).28 In order to understand the relationship between the calculated molecular properties (cLogP and PSA) and hepatoselectivity for this hydroxypyridone lead series, and to use the former as a prediction of the latter to enable prospective designs, we assembled a list of compounds that spanned a range of lipophilicity (cLogP = 0.5–4) and polar surface area (PSA = 105–180) and measured their Papp. As can be seen from Figure 4, PSA > 130 Å2 increased the probability of the desired permeability (Papp < 5 × 10–6 cm/s), and generally, PSA > 130 Å2 correlated to cLogP < 3 for these compounds. Therefore, in silico calculation of PSA and cLogP was used for prioritizing targets.

Figure 4.

PSA values of >130 Å2 increases the probability of the desired permeability (Papp < 5 × 10–6 cm/s).

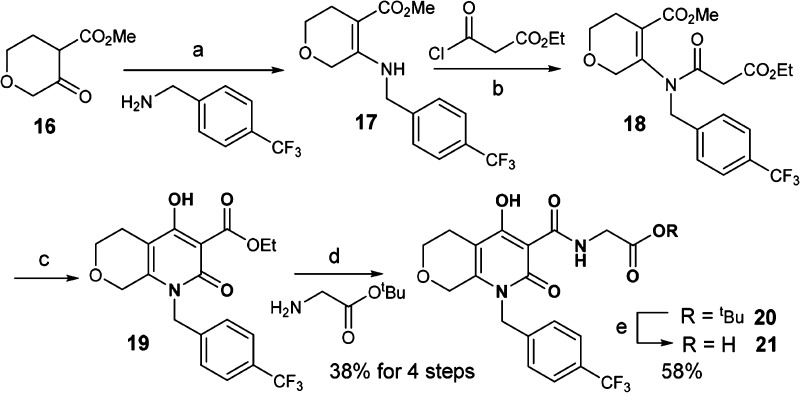

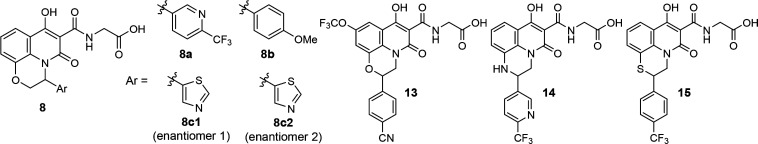

The synthesis of the hydroxypyridone analogues for SAR studies is described in Schemes 1–4.22 Reaction between aminophenol 2 and α-bromo ketone 3 provided cyclic imine 4. Upon reduction, the resulting aniline 5 was condensed with triethylmethanetricarboxylate to afford tricyclic core 6. Amide formation with tert-butyl glycinate, followed by hydrolysis of the ester, completed the synthesis of tricyclic analogues 8 (see Scheme 1).29

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Tricyclic Analogues 8.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Bu4NHSO4, aqueous K2CO3, dichloromethane; (b) NaBH3CN, acetic acid, dichloromethane/methanol; (c) triethylmethanetricarboxylate, 200 °C; (d) iPr2EtN, toluene, reflux; (e) TFA, dichloromethane.

Scheme 4. Synthesis of Bicyclic Analogues 27 and 28.

Reagents and conditions: (a) IPA, 100 °C; (b) K2CO3, acetone, 40 °C; and (c) TFA, dichloromethane.

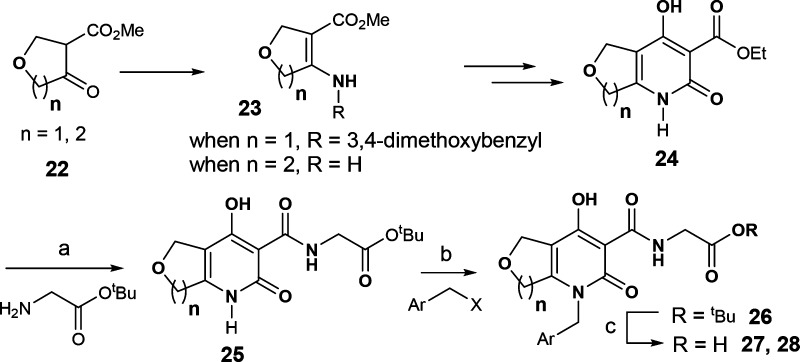

Similarly, the regioisomeric tricyclic analogues 13 and 15 were synthesized starting with cyclization between substituted aniline 9 and an α-bromo ester to provide lactam 10 (see Scheme 2). Reduction of amide 10 gave cyclic aniline 12 (X = O or S). For compound 14, intermediate 12 (X = NH) was obtained through another two-step sequence: Suzuki coupling and borane reduction. Finally, intermediate 12 was converted to 13–15, following the same procedures described for 8.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Tricyclic Analogues 13–15.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Base, toluene, 120 °C; (b) BH3-Me2S, THF, from 0 °C to room temperature (rt); (c) (6-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-3-yl)boronic acid, Pd(Ph3P)4, K2CO3, dioxane/water, 90 °C; and (d) BH3-THF, THF, rt.

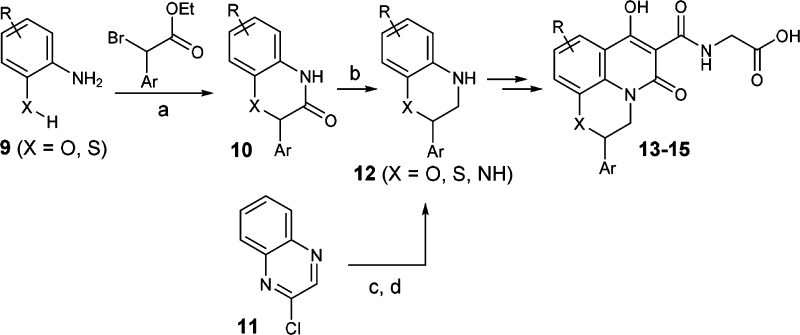

Scheme 3 illustrates the synthesis of the bicyclic analogue 21. β-Keto ester 16 was condensed with p-CF3-benzylamine to afford enamine 17. Acylation of 17 gave compound 18, which was engaged in a Dieckmann-type reaction to arrive at core structure 19.30 Finally, amide formation and hydrolysis of the tert-butyl ester provided the bicyclic analogue 21.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Bicyclic Analogue 21.

Reagents and conditions: (a) ethanol, acetic acid, 90 °C; (b) CH3CN, 70 °C; (c) NaH, toluene/ethanol; (d) DME, iPr2EtN, 90 °C; and (e) TFA, dichloromethane.

While the synthetic route in Scheme 3 would allow access to many bicyclic analogues described herein, an efficient synthesis to rapidly explore the SAR of the benzyl portion was needed. As illustrated in Scheme 4, pyridone 24 was synthesized via enamine 23 as a key intermediate. After amide formation with tert-butyl glycinate, advanced intermediate 25 provided access in two steps, including alkylation and ester hydrolysis, to final products 27 and 28 with diverse benzyl groups.31,32

For the engagement of OATPs, we took advantage of the carboxylic acid moiety of lead compound 1, and designed a series of tricyclic analogues to probe liver selectivity. As shown in Table 1, diverse structural features were tolerated in terms of potency, where the third ring could be a morpholine (8 and 13), piperazine (14), or thiomorpholine (15), and the aromatic group (Ar) could be attached at either position of the ethylene (8 vs 13–15). However, despite the calculated PSA being >130 Å2 (except for compound 15) and clogP < 3, which enriched the measured Papp of <5 × 10–6 cm/s, these tricyclic analogues exhibited suboptimal liver/plasma ratios in rat (<8).

Table 1. SAR Study of the Tricyclic Analogues.

| compound | hPHD1a IC50 (nM) | hPHD2a IC50 (nM) | hPHD3a IC50 (nM) | PSAc (Å2) | cLogPd | Papp (× 10–6 cm/s) | liver/plasma ratioe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8a | 4.9 ± 3.3 | 6.1 ± 4.2 | 8.9 ± 3.8 | 140 | –1.1 | 3.1 | 1.0 |

| 8b | 27 ± 14 | 27 ± 4.0 | 21 ± 5.8 | 139 | –0.2 | 7.4 | 6.2 |

| 8c1 | 7.4 ± 1.4 | 15 ± 3.5 | ndb | 143 | –1.9 | <2.3 | 2.5 |

| 8c2 | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | ndb | 143 | –1.9 | <1.8 | 4.4 |

| 13 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 165 | –0.5 | ndb | 7.9 |

| 14 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 142 | –1.4 | ndb | 3.9 |

| 15 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 13 ± 2.7 | 115 | 1.7 | <8.6 | 7.5 |

Human HIF-PHD IC50 data expressed as mean ± SD (n ≥ 2 independent experiments).

Not determined.

PSA was calculated using the TPSA method published in J. Med. Chem.2000, 43, 3714–3717.

cLogP was calculated at pH 7.4, using ACD Percepta software.

Total liver/plasma ratio at 4 h (10 mg/kg PO).

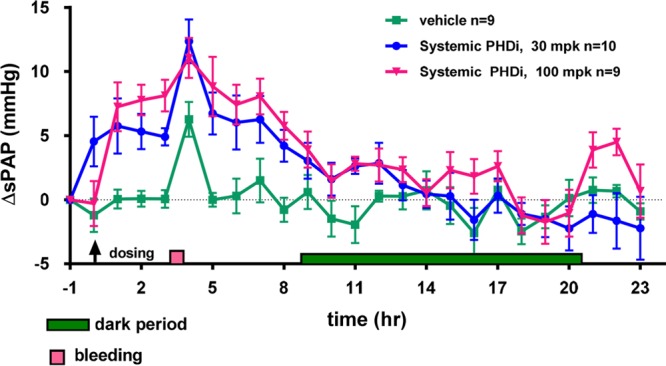

Therefore, we focused our efforts on the bicyclic series where a tetrahydropyran or tetrahydrofuran ring is fused with the hydroxypyridone (see Table 2). Again, the analogues with PSA values of greater than ∼130 Å2 and clogP < 3 were prioritized for synthesis. Several trends were observed. The bicyclic analogues exhibited much higher liver selectivity than the tricyclic analogues, despite similar PSA, cLogP, and Papp values. Within the bicyclic series, one pyran regioisomer was significantly more liver selective than the other (27a vs 21, liver/plasma ratio 107 vs 10), and furan analogues were more potent than their pyran counterparts (28a vs 21, 27a; 28b vs 27b; and 28g vs 27d). Finally, the in silico parameters PSA and cLogP were indeed a useful tool in predicting Papp for this chemical matter.

Table 2. SAR Study of the Bicyclic Analogues.

| compound | hPHD1a IC50 (nM) | hPHD2a IC50 (nM) | hPHD3a IC50 (nM) | PSAd (Å2) | cLogPe | Papp (× 10–6 cm/s) | liver/plasma ratiof |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28c | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 5.8c | 139 | 1.3 | 5.2 | 22 |

| 21 | 11 ± 2.1 | 20 ± 1.1 | 40 ± 5.6 | 128 | 0.9 | 7.3 | 10 (31) |

| 27a | 14 ± 7.3 | 19 ± 11 | 51 ± 3.9 | 128 | 1.1 | 4.0 | 107 |

| 27b | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 8.5 ± 1.6 | 33 ± 4.2 | 128 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 216 |

| 27c | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 9.0 ± 0.8 | 18 ± 1.1 | 152 | –0.2 | ndb | 74 |

| 27d | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 11 ± 3.3 | 41c | 140 | –0.4 | <1.7 | 126 |

| 27e | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 5.4 ± 3.2 | 14c | 142 | 1.2 | <2.1 | 217 |

| 28a | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 4.9 ± 1.8 | 8.2 ± 3.3 | 126 | 1.0 | 4.2 | 16 (38) |

| 28b | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 6.4 ± 2.4 | 130 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 39 |

| 28d | 6.2 ± 2.1 | 6.9 ± 3.6 | 16 ± 4.7 | 149 | –0.1 | <1.5 | 210 |

| 28e | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 8.8 ± 5.0 | 129 | 0.5 | <2.2 | 50 |

| 28f | 3.1 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 2.9 | 6.6c | 129 | 0.6 | ndb | 87 |

| 28g | 3.6c | 5.3c | 13c | 142 | –0.5 | <1.7 | 166 |

| 28h | 11 ± 1.3 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 18 ± 6.2 | 157 | –1.1 | ndb | 63 |

| 28i | 12 ± 2.7 | 10 ± 0.2 | 22 ± 0.2 | 155 | –0.7 | ndb | 48 |

| 28j | 4.9 ± 2.6 | 4.9 ± 2.6 | 13 ± 3.2 | 154 | –1.5 | ndb | 359 (952) |

| 28k | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 6.4 ± 1.3 | 145 | –0.1 | <1.5 | 212 |

| 28l | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 143 | 0.5 | ndb | 587 |

| 28m | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 143 | 0.3 | ndb | 69 |

| 28n | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | 6.6c | 156 | 0.6 | <1.9 | 60 |

Human HIF-PHD IC50 data expressed as mean ± SD (n ≥ 2 independent experiments), unless noted otherwise.

Not determined.

Measured only once.

PSA was calculated using the TPSA method published in J. Med. Chem.2000, 43, 3714–3717.

cLogP was calculated at pH 7.4 using ACD Percepta software.

Total liver/plasma ratio at 4 h post-dose (10 mg/kg PO); unbound liver/plasma ratio is given in parentheses (where available). Generally, the unbound fraction was higher in liver than in plasma, and the unbound ratio was ∼3 times greater than the total ratio for this series of analogues.

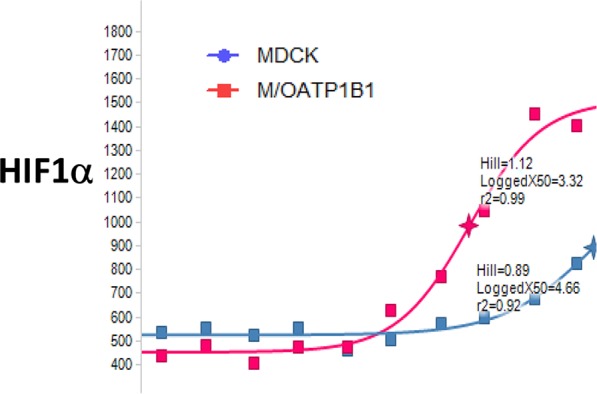

Our strategy to use a carboxylic acid moiety as the OATP recognition element and design away from passive transport was verified by HIF1α assay in MDCK and MDCK/hOATP1B1 cells (see Figure 5).22 Compound 28a, a low permeability compound, did not show HIF1α activity in MDCK cells (blue line), but the activity was boosted in MDCK/hOATP1B1 cells (red line) suggesting 28a was actively transported via a human OATP.

Figure 5.

HIF1α assay of 28a in MDCK and MDCK/hOATP1B1 cells.

One potential limitation of achieving liver selectivity by relying on OATPs and reduced permeability is that, as a compound becomes less permeable, its oral absorption is typically impeded. Therefore, choosing the appropriate level of permeability is critical to balancing hepatoselectivity and oral absorption in a compound. Compound 28a was selected for further profiling, because of its appropriate permeability that led to a good hepatoselectivity (unbound liver:plasma = 38:1), as well as acceptable PK properties across the species (see Table 3).

Table 3. Pharmacokinetic Profile of Compound 28aa.

Vehicles for rat, iv and po: PEG200/HPCD/water (30:12:58, v/v/v). Vehicles for dog, iv: PEG200/HPCD/water (30:12:58 v/v/v); po: Imwitor/Tween (1:1 w/w).

1 mg/kg iv, 2 mg/kg po.

0.175 mg/kg iv, 1 mg/kg po.

An off-target screen of this compound was performed against a panel of 168 receptors, ion channels, and enzymes, and only one off-target activity was found with IC50 < 10 μM (leukotriene, cysteinyl CysLT2: IC50 = 4.5 μM). Compound 28a had no effects on cardiac ion channels (IC50 of iKr > 60 μM, Nav1.5 > 30 μM, Cav1.2 > 30 μM) and was also selective over CYP 3A4 (IC50 > 50 μM) and hPXR (EC50 > 30 μM, 1% Act).33

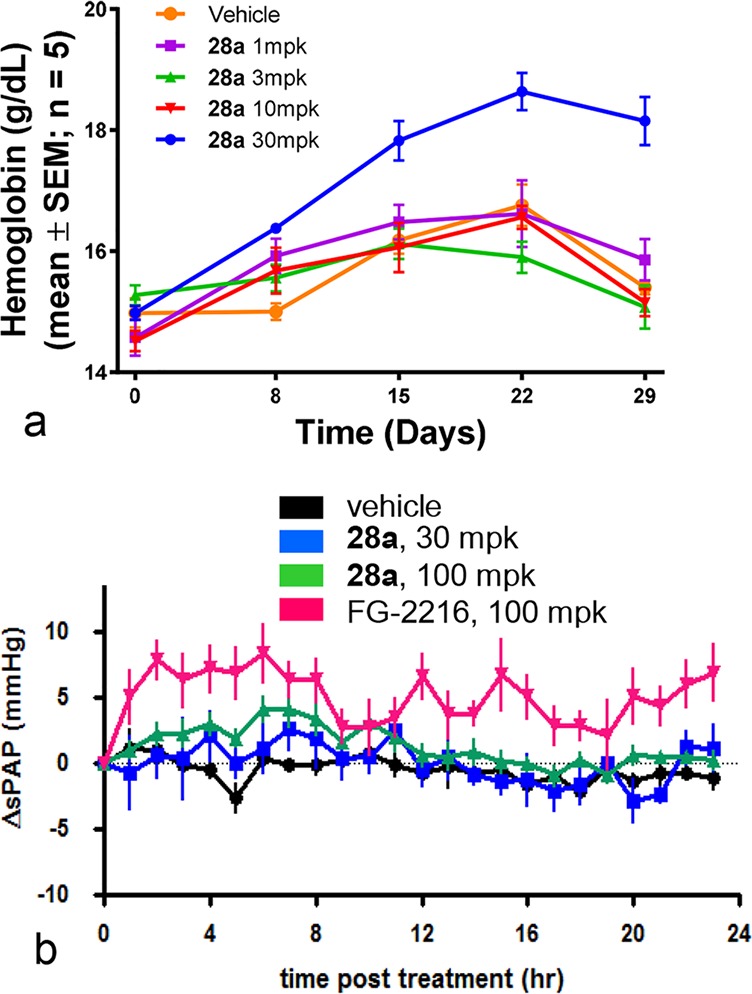

With the promising PK and selectivity profile, 28a was further characterized pharmacodynamically. As shown in Figure 6, a significant increase in hemoglobin was observed, following a 4 week treatment of 28a in rat (QD, PO) at 30 mpk (Figure 6a), and based on this data, the minimal efficacious dose (MED) should be ∼30 mpk. In the rat telemetry study (Figure 6b), 28a showed no effect on the pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) in rat at 100 mg/kg, roughly 3×MED. On the other hand, systemic HIF-PHD inhibitor FG-2216 caused an increase in PAP at 50 mpk. Therefore, these studies have demonstrated that liver-selective inhibition of HIF-PHD drives useful increases in hemoglobin separate from systemic side effects.

Figure 6.

In vivo studies of 28a in rat: (a) chronic PD study where significant hemoglobin increase was observed at 30 mpk; (b) rat telemetry study where no effect on PAP was observed at 3×MED.

In summary, we have designed and synthesized a series of bioavailable and liver-targeted HIF-PHD inhibitors that may be used for the treatment of anemia. We relied on organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs) to achieve liver selectivity. A major focus of the optimization effort was to decrease the passive cell permeability to achieve hepatoselectivity, and simultaneously balance molecular properties to achieve acceptable bioavailability. These efforts led to the identification of compound 28a that possessed excellent potency in vitro, liver selectivity, and acceptable PK properties. This compound significantly increased hemoglobin in rat following chronic QD oral administration and displayed selectivity over systemic effects. Further optimization to improve the overall PK profile will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank the department of Laboratory Animal Resources for their assistance in animal dosing and sampling.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00274.

Synthetic procedures and characterization data of selected compounds, conditions for the biological assays, and protocol for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies (PDF)

Author Present Address

□ Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ.

Author Present Address

☆ Merck Research Laboratories, Boston, MA.

Author Present Address

@ Merck Research Laboratories, West Point, PA.

Author Present Address

∇ Merck Research Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Beutler E.; Waalen J. The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration?. Blood 2006, 107, 1747–1750. 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilayur E.; Harris D. C. H. Emerging therapies for chronic kidney disease: what is their role?. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2009, 5, 375–383. 10.1038/nrneph.2009.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlewood T. J.; Collins G. P. Pharmacotherapy of anemia in cancer patients. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 1, 307–317. 10.1586/17512433.1.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavill I.; Auerbach M.; Bailie G. R.; Barrett-Lee P.; Beguin Y.; Kaltwasser P.; Littlewood T.; Macdougall I. C.; Wilson K. Iron and the anaemia of chronic disease: a review and strategic recommendations. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2006, 22, 731–737. 10.1185/030079906X100096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss G.; Goodnough L. T. Anemia of chronic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1011–1023. 10.1056/NEJMra041809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelkmann W. Developments in the therapeutic use of erythropoiesis stimulating agents. Br. J. Haematol. 2008, 141, 287–297. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohlawetz P. J.; Dzirlo L.; Hergovich N. Effects of erythropoietin on platelet reactivity and thrombopoiesis in humans. Blood 2000, 95, 2983–2989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L.; Colandrea V. J.; Hale J. J. Prolyl hydroxylase domaincontaining protein inhibitors as stabilizers of hypoxia-inducible factor: small molecule-based therapeutics for anemia. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2010, 20, 1219–1245. 10.1517/13543776.2010.510836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano R.; Fadda G.; Bernardo M.; James C.; Kochendoerfer G.; Lee T.; Nakayama S.; Neff T.; Piper B. A. FG2216, a novel oral HIF-PHI, stimulates erythropoiesis and increases hemoglobin concentration in patients with non-dialysis CK. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2008, 51, B80. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.02.222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roxadustat (FG-4592) met the primary endpoints in two Chinese Phase III trials to treat anemia in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients; see: http://bciq.biocentury.com/products/asp1517.

- Maxwell P. H.; Eckardt K.-U. HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors for the treatment of renal anaemia and beyond. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 157–168. 10.1038/nrneph.2015.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joharapurkar A. A.; Pandya V. B.; Patel V. J.; Desai R. C.; Jain M. R. Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors: A Breakthrough in the Therapy of Anemia Associated with Chronic Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 6964–6982. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck H.; Jeske M.; Thede K.; Stoll F.; Flamme I.; Akbaba M.; Erguden J.-K.; Karig G.; Keldenich J.; Oehme F.; Militzer H.-C.; Hartung I. V.; Thuss U. Discovery of Molidustat (BAY 85–3934): A Small-Molecule Oral HIF-Prolyl Hydroxylase (HIF-PH) Inhibitor for the Treatment of Renal Anemia. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 988–1003. 10.1002/cmdc.201700783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vachal P.; Miao S.; Pierce J. M.; Guiadeen D.; Colandrea V. J.; Wyvratt M. J.; Salowe S. P.; Sonatore L. M.; Milligan J. A.; Hajdu R.; Gollapudi A.; Keohane C. A.; Lingham R. B.; Mandala S. M.; DeMartino J. A.; Tong X.; Wolff M.; Steinhuebel D.; Kieczykowski G. R.; Fleitz F. J.; Chapman K.; Athanasopoulos J.; Adam G.; Akyuz C. D.; Jena D. K.; Lusen J. W.; Meng J.; Stein B. D.; Xia L.; Sherer E. C.; Hale J. J. 1,3,8-Triazaspiro[4.5]decane-2,4-diones as Efficacious Pan-Inhibitors of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase 1–3 (HIF PHD1–3) for the Treatment of Anemia. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 2945–2959. 10.1021/jm201542d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debenham J. S.; Madsen-Duggan C.; Clements M. J.; Walsh T. F.; Kuethe J. T.; Reibarkh M.; Salowe S. P.; Sonatore L. M.; Hajdu R.; Milligan J. A.; Visco D. M.; Zhou D.; Lingham R. B.; Stickens D.; DeMartino J. A.; Tong X.; Wolff M.; Pang J.; Miller R. R.; Sherer E. C.; Hale J. J. Discovery of N-[Bis(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-4-hydroxy-2-(pyridazin-3-yl)pyrimidine-5-carboxamide (MK-8617), an Orally Active Pan-Inhibitor of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase 1–3 (HIF PHD1–3) for the Treatment of Anemia. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 11039–11049. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza G. L. Regulation of mammalian O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1999, 15, 551–578. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The HIF-PHD inhibitors, including FG-2216, that have reached phase 2 or 3 clinical trials did not show any toxicity related to pulmonary arterial hypertension thus far.

- Jelkmann W. Erythropoietin: structure, control of production, and function. Physiol. Rev. 1992, 72, 449–489. 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. K.; Waypa G. B.; Mungai P. T.; Nielsen J. M.; Czech L.; Dudley V. J.; Beussink L.; Dettman R. W.; Berkelhamer S. K.; Steinhorn R. H.; Shah S. J.; Schumacker P. T. Regulation of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension by vascular smooth muscle hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, 314–324. 10.1164/rccm.201302-0302OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamishima Y. A.; Kaelin W. G. Jr. Reactivation of Hepatic EPO Synthesis in Mice After PHD Loss. Science 2010, 329, 407. 10.1126/science.1192811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams M. T.; Koser M.; Burchard J.; Strapps W.; Mehmet H.; Gindy M.; Zaller D.; Sepp-Lorenzino L.; Stickens D. A Single Dose of EGLN1 siRNA Yields Increased Erythropoiesis in Nonhuman Primates. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2014, 24, 405–412. 10.1089/nat.2014.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See the Supporting Information for experimental details.

- Smith N. F.; Figg W. D.; Sparreboom A. Role of the liverspecific transporters OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 in governing drug elimination. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2005, 1, 429–445. 10.1517/17425255.1.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erion M. D.; Bullough D. A.; Lin C.-C.; Hong Z. HepDirect prodrugs for targeting nucleotide-based antiviral drugs to the liver. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs 2006, 7, 109–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuya T.; Kuroda S. Nanoparticles for human liver-specific drug and gene delivery systems: in vitro and in vivo advances. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 2009, 6, 39–52. 10.1517/17425240802622096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compound 1 was from our internal systemic HIF-PHD program (unpublished results).

- Liu X.; Testa B.; Fahr A. Lipophilicity and Its Relationship with Passive Drug Permeation. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 962–977. 10.1007/s11095-010-0303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veber D. F.; Johnson S. R.; Cheng H.-Y.; Smith B. R.; Ward K. W.; Kopple K. D. Molecular Properties That Influence the Oral Bioavailability of Drug Candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2002, 45, 2615–2623. 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Also see: Cai J.; Crespo A.; Du X.; Dubois B. G.; Guiadeen D.; Kothandaraman S.; Liu P.; Liu R.; Quan W.; Sinz C.; Wang L.. Oxazinoquinolinecarboxamidoacetic acid derivatives as inhibitors of HIF prolyl hydroxylase and their preparation, International Patent No. WO 2016045127, 2016.

- Dieckmann W. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1894, 27, 102–103. 10.1002/cber.18940270126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For synthesis of 27, also see: Cai J.; Colandrea V.; Crespo A.; Debenham J.; Du X.; Guiadeen D.; Liu P.; Liu R.; Madsen-Duggan C. B.; McCoy J. G.; Quan W.; Sinz C.; Wang L.. Quinolinecarboxamidoacetic acids and related compounds as inhibitors of HIF prolyl hydroxylase and their preparation, International Patent No. WO 2016045125, 2016.

- For synthesis of 28, also see: Cai J.; Crespo A.; Du X.; Dubois B. G.; Liu P.; Liu R.; Quan W.; Sinz C.; Wang L.. Tetrahydrofuropyridineecarboxamidoacetic acid derivatives as inhibitors of HIF prolyl hydroxylase and their preparation, International Patent No. WO 2016045128, 2016.

- Pregnane X receptor (PXR) is a nuclear receptor known to regulate expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes including cytochrome P450 (CYP450), see:Chu V.; et al. In vitro and in vivo induction of cytochrome P450: A survey of the current practices and recommendations: A Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America perspective. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009, 37, 1339–1354. 10.1124/dmd.109.027029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.