Abstract

Objectives

Although patient education is recommended to facilitate the transition from pediatric to adult care, a consensus has not been reached for a particular model. The specific skills needed for the transition to help in facilitating the life plans and health of young people are still poorly understood. This study explored the educational needs of young people with diverse chronic conditions during their transition from pediatric to adult care.

Methods

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 young people with chronic conditions. A thematic analysis was conducted to examine the data.

Results

Five themes emerged from the data, identified through the following core topics: learning how to have a new role, learning how to adopt a new lifestyle, learning how to use a new health care service, maintaining a dual relationship with pediatric and adult care, and having experience sharing with peers.

Conclusion

A shift in perspective takes place when the transition is examined through the words of young people themselves. To them, moving from pediatric to adult care is not viewed as the heart of the process. It is instead a change among other changes. In order to encourage a transition in which the needs of young people are met, educational measures could focus on the acquisition of broad skills, while also being person-centered.

Keywords: transition, adolescence, chronic disease, pediatrics, patient education

Introduction

During youth, young people with chronic conditions face an unprecedented period of instability which comes with many changes. They gain in autonomy when managing their illness (the latter having previously been largely managed by their parents), they undergo somatic and mental upheavals, and they leave pediatric care to move to adult care.1 Breaks in medical follow-up, nonadherence to treatment, and unhappiness are more frequent during this period.2–4

Developmentally appropriate health care (DAH) is recommended to help young people face these changes and for them to learn progressively how to grow up with a chronic illness. Young people (defined by WHO as 10–24 years of age)5 need a form of adaptive health care that is different from the one children and adults6 receive. DAH recognizes the changing biopsychosocial developmental needs of young people and their need for empowerment.7 DAH relates to pediatric and adult care and the transition between both services. In this perspective, transition is more than the movement from pediatric to adult care (the latter of which is called a transfer). Transition is a period of global changes (pubertal, psychological, social, academic/professional, and of health care services). It needs to be prepared in an organized and coordinated transition process, thus enabling young people to optimize their development, life plan, and health.8,9

In a systematic review, Crowley et al10 showed the importance of patient education to empower young people and to optimize their health during transition. Patient education is a process which enables young people to acquire and retain skills that help them maintain a healthy lifestyle given their illness.11 Different models exist (applicable to all chronic conditions). Schwartz et al12 developed a socio-ecological model in which young people’s environment is highlighted as being a major influence and includes young people’s interactions with their parents and their caregivers when acquiring self-care skills and autonomy. Reed-Knight et al13 underscored the role of parents in the development of self-care skills and skills related to communicating with the medical staff. Modi et al14 presented a model of pediatric self-management (focused on treatment management) that outlined the levels of influence of the individual, the family, the community, and the health care system. While these models provide solutions that help young people learn to become more empowered when managing their illness and their treatment and when moving to adult care, they remain vague regarding operational educational objectives, especially those aimed at supporting young people’s psychosocial development and daily lives (eg, what type of educational objectives can be offered to learn to cope with social life, or to cope with a new way of thinking about oneself, or to manage lifestyle skills?). More recently, Schmidt et al15,16 offered a detailed patient education program for transition. It consists of a 2-day transition workshop before the transfer and aims to improve the overall skills of young people in relation to their biopsychosocial needs. It is, however, more of a transfer-centered program than a form of patient education within a transition process: the progressive changes experienced by young people cannot be managed in a 2-day workshop, as the time of transition lasts many years.

Actually a consensus has not been reached around one particular transition-oriented patient education model. While patient education is a process that enables young people to acquire skills to live with a chronic illness, the specific skills needed for young people to go through a transition that is more in tune with their life plans and their health are not well known.1,15 We have little information about how young people learn to cope with changes during this period. A recent review of the literature17 showed that research on transition is primarily focused on organizational needs and does not frequently explore the lived experience of young people. Two reasons can explain this: samples are only composed of experts and/or health professionals, or quantitative methods are used.16 These approaches do not allow researchers to study the internal logics of young people and their behavior toward their health. For this, qualitative methods are indeed preferred.18,19 The latter methods had been overlooked in studies with young people under the pretext that this age group lacked the ability to understand and verbalize their experience, a point which has since been completely refuted by research.20

Using a qualitative method, our study therefore aims to explore the educational needs felt by young people with a chronic condition during transition in their daily lives. We aimed to identify 1) educational needs relating to the development of self-care skills, 2) informational needs relating to managing exploratory health behaviors (eg, emotional and sexual life, smoking, alcohol, drugs, etc), and 3) psychosocial needs relating to young people’s coping mechanisms. Needs related to the change in medical services are also examined. The objective is to better understand young people’s experience of transition, how the educational needs cited above and the event of transfer are important for them in their daily life, how they learn to cope with the changes during transition, and what their needs are to optimize their learning.

Methods

Methodological approach

A qualitative design was adopted and featured semi-structured interviews, which were analyzed through thematic analysis. The thematic analysis allowed us to study the themes identified within the interviews both through deductive (ie, theory-driven) and inductive (ie, data-driven) means.21,22 We first stipulated, based on adolescent health literature,23–25 that young people had needs that corresponded to the categories of needs cited above (self-care needs, lifestyle management needs, and psychosocial needs). These categories inspired our questioning (Box 1). The questions aimed to clarify each category by exploring how the changes of the transition period impacted young people’s needs, since little information is available on this topic at this time. We also remained attentive to the emergence of new categories which could come up during the interviews.

Sampling

Sampling was purposively targeted and not random, with a selection strategy based on criteria. To participate in the study, young people had to 1) live with a chronic condition and 2) be involved in, or close to, the transfer (move to adult care in <1 year or having moved to adult care for <2 years). The range of age we settled upon was from 15 to 25 years, since transfers that occur before 16 and after 21 are very rare in France. Thanks to this range, we were able to recruit young people who were both undergoing developmental changes and who were involved in a transfer from pediatric to adult care. Young people with cognitive impairment and/or who did not master the French language proficiently enough to participate in interviews were excluded from the study.

Box 1. Interview guide.

| •Can you tell me how you manage your illness and your treatments now that you are becoming an adult? •How would you react if you had an incident once you were cared for by adult care? •How would you describe adult care? •Can you tell me what you think is important for adolescents to know before they leave the pediatric unit? •What are your feelings about leaving the pediatric service? •How would you describe a young person with your condition who goes in for adult care? •How important is your illness in your life? •Do you have specific interests in certain health topics? •Who do you talk to if you have questions about alcohol, tobacco, drugs, sexuality, etc? •What is your life plan? •Is there anything you consider important that we have not discussed today? |

Young people were recruited in three hospitals in France: Amiens University Hospital, Necker Hospital, and Jean Verdier Hospital.

We purposefully chose a sampling strategy that targeted maximum variation. We aimed to recruit young people with diverse chronic pathologies in order to identify the invariant elements among a potential variety of educational needs. Since young people living with a rare disease could have an experience that was more difficult due to heavy treatments and complex care than that of young people living with a prevalent disease,26 we sought to have a balanced proportion of both categories of young people living with a chronic illness. Such a precaution was meant to avoid gathering information that would be determined by the nature of the young people’s diseases. It also served to identify the requirements linked to a particular type of disease from those which were common to all young people. Diseases are defined as rare when they affect <1 person out of 2,000, according to European Union standards.27 We also wished to recruit young people who were at different stages in the transition process: both before and after transfer to adult care (“pre-transfer” and “post-transfer”). In this way, the needs that were felt and anticipated before moving to adult care were collected, as were the needs felt after the transfer to adult care. The process as a whole was therefore studied. Finally, distinct hospital environments were represented in an effort to increase the probability of hearing from young people with sociologically diverse backgrounds (the three hospitals are in three regions with three different sociologic realities: the city, the suburbs, and the countryside) and who had been cared for by caregivers with different practices. Once more, we sought to find a balanced proportion between these categories.

Thanks to these selection conditions, we were able to gain maximum variation sampling to understand how transition in the daily life of young people is seen and understood among different young people, in different settings, and at different times.28 Maximum variation sampling is indeed characteristic of this type of method when multiple facets of a theme are to be explored. Such variation led to the richness of the data.29 This method is aligned with our research objective, in which we aim to identify the educational needs common to young people with diverse pathologies during the transition.

Procedure

The heads of pediatric and adult services in the aforementioned hospitals who cared for young people with a chronic condition were contacted and asked to notify young people who corresponded to the study’s inclusion criteria. The doctors presented the study at the hospital to young people who met the inclusion criteria and gave them an informational document written by the main investigator (MM). Each doctor was asked to present the study to a maximum of five young people to respect the maximum variation sampling. When young people agreed to participate in the study and parents of underage participants agreed to let their child participate in the study, the doctor gave the contact details to the main investigator (MM). Written consent from the young people and the parents of underage young people was required to participate in the study. Meetings for a face-to-face interview were organized by phone or text messaging with the main investigator (MM). Four young people did not answer the calls and text messages. We do not have formal data relative to the number of young people who were notified of the study by their doctor and who may have refused to participate at that time. However, three cases of refusal were reported to us (two at the Jean-Verdier hospital and one at the Amiens hospital). Participation was completely voluntary. The young people were not provided with any form of reimbursement.

Face-to-face interviews took place in the hospital in which the young people were cared for and were led by the main investigator (MM). Young people were not hospitalized at the time of the interview, but reported to the hospital for a consultation. One interview took place as a teleconference and another was conducted over the telephone for reasons linked to the young person being geographically removed from the hospital. Interviews lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour and were recorded with a digital recorder.

Basic sociodemographic data (age, study level, or profession) were collected at the beginning of the interview with the young people.

Data analysis

The principles of thematic analysis30 were applied to analyze the data. Interviews were transcribed verbatim. Two researchers in health education, who were exterior to the study, discussed and agreed on the analysis and on whether the themes and codes that had been identified corresponded to the verbatim. Quotes and transcripts were translated from French to English by a professional translator for inclusion in this article.

Since thematic analysis is a method that is selective and shaped by the objectives of the research, we identified semantic categories pertaining to the educational needs felt by young people based on their experience of transition in their daily lives. We defined the needs as the gap between the person’s current situation and his/her desired situation.31 Needs were identified through semantic clues such as “I would need…”, “there should be…”, “I wonder if…”, “I’m afraid that…”, “I don’t know how to…”, “I would like…”, “it’s hard…”, “it’s important…”, “it embarrasses me…”, “I don’t feel like I can…”, etc. We cut the text corpus transversely to extract the elements that referred to a same theme in the various interviews. The manner of cutting the text corpus was stable from one interview to another.

The meaning saturation principle32 was used to decide when to stop the research. This principle reposes on determining whether the questions brought about in the research are sufficiently and relevantly posed in the interviews, to the point at which a new interview would not provide a renewed understanding of the phenomenon. Two interviews were still conducted when saturation was obtained and no new information on the educational needs felt by young people was collected.

This study complied with the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research guidelines for qualitative research.33

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Young people and parents of underage young people participating in the study were informed and provided written consent. The informational document mentioned that a psychologist from the hospital was available to receive the young people after their interviews. The main investigator’s (MM) contact details were provided, as was his availability to answer any questions about the study.

The study was approved by the Ethics Evaluation Board for Health Research (no. 201713), the Advisory Committee on the Treatment of Information in the field of Research (no. 16-311), and the National Commission on Computer Technology and Freedom (no. 1984766 v0) in France.

Data anonymity was guaranteed.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Seventeen young people were interviewed (ten women and seven men). The average age was 18.2 years (SD ±1.8). Seven young people were in pre-transfer (pediatric care) and ten young people were in post-transfer (adult care). Eight young people suffered from prevalent diseases (type 1 diabetes, HIV, epilepsy) and nine had rare diseases (mastocytosis, multiple sclerosis, sickle-cell anemia, β-thalassemia, liver transplantation, cystic fibrosis). Seven young people came from Necker Hospital, six others from Amiens University Hospital, and four more were from Jean Verdier Hospital (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample description

| Characteristic | N=17 |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Average age | 18.2 |

| Gender (n) | |

| Female | 10 |

| Male | 7 |

| Pathology (n) | |

| Type 1 diabetes | 5 |

| Liver transplantation | 3 |

| HIV | 2 |

| Sickle-cell anemia | 2 |

| Epilepsy | 1 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 |

| β-Thalassemia | 1 |

| Mastocytosis | 1 |

| Type of pathology (n) | |

| Prevalent | 8 |

| Rare | 9 |

| Transition (n) | |

| Pre-transfer | 7 |

| Post-transfer | 10 |

| Hospital center (n) | |

| Amiens University Hospital Center | 6 |

| Necker Hospital | 7 |

| Jean-Verdier Hospital | 4 |

The study respected the sampling strategy that targeted maximum variation with a balanced proportion between the different categories of young people.

The young people’s experience of transition

The analysis of the verbatim reports revealed that the needs expressed by young people came as a result of changes that were taking place in their lives during the transition period. Five themes and 23 respective codes were identified (Table 2). They are invariant regardless of the types of diseases and the young people’s locations.

Table 2.

List of identified themes and breakdown of relative codes

| Themes | Codes |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Learning a new role with an illness | Afraid of being categorized as “sick”; negative attitude toward the illness; comparing oneself to non-diseased individuals; sense of injustice (why me?) |

| •As a human being | |

| • Being responsible for the illness and its treatment | Learning from parents; feeling of self-efficacy |

| • As a patient | Participation in the decision; willingness to be viewed as an adult |

| Learning a new lifestyle | A need for information on general health matters; not identifying health care professionals as resources for health questions |

| Learning a new health care service | The change is not perceived in relation to oneself; the change is mostly perceived in relation to the parents; peace of mind regarding the change; the change is grasped after the fact; a modification in the relationship with the health care personnel; more biomedical consultations in the adults’ unit; administrative management is difficult to handle |

| Maintaining a dual relationship with pediatric and adult care | Trusting the pediatric doctor more for urgent or personal questions; needing time to trust new health care professionals; a sense of security provided by the dual relationship with pediatric and adult services |

| Having experience sharing with peers | Exchanging tips and tricks to live with the illness; sharing similar experiences; a common vocabulary |

Theme 1: learning a new role with an illness

A new role as a human being

For the young people being interviewed, becoming an adult with an illness primarily amounts to forging one’s identity and social place. But the illness can sometimes complicate the process. Some young people therefore expressed a negative attitude toward their illness: it seemed to prevent them from being who they wanted to be or who they would like to become (feeling a sense of weariness toward the treatment and toward consultations).

I don’t like hospitals. I’m fed up because I’ve been coming here since I was very little. I’m fed up with the medicine. I’ve been traumatized by the pills. [Young person 5]

The illness is seen as taking up too much space in some of the young people’s lives and in the ways they perceive themselves (a cognitive load due to the attention paid to the illness, being “sick” first and “young” second). A fear of being categorized was also expressed (being perceived by others as only being “sick”). Young people want to learn to be more than just a sick person toward themselves, in their daily life and in social life. According to the young people who were interviewed, patient education interventions at the hospital simply amounted to learning self-care skills. In this way, patient education often reminded young people that they were “sick”. This could, in turn, lead certain young people to reject this form of education.

(Young person 1) When I was younger, I didn’t think about my illness. But now that I’m older, I think about the fact that this illness is really going to ruin my life. Because I know that I’ll always have problems. I’ll never be like everyone else.

(Young person 9) I’m always afraid of the way people will react if I talk about my illness. I feel like I expose myself any time I talk about it. After that, people know my weaknesses.

(Young person 8) I do not want them (the caregivers) to teach me how to treat me. I’m sick of being told about my illness all the time.

Young people can feel excluded from various communities because of their health and social comparison can bring about negative feelings. Young people would like to know how to manage better their social identity and social life with other young people.

(Young person 17) Sometimes I’m sad when I see my friends doing things I can’t do.

Finally, existential types of questions were articulated (why me? Why is my life more complicated than the lives of my peers?). According to young people, these themes are not discussed with their caregivers. And yet, some young people need guidance or a listening ear regarding these questions before being ready to learn self-care skills. There is a requirement for caregivers to be attentive to emotional, existential, and personal concerns as these are major concerns for young people at this stage in their lives.

(Young person 3) Being diabetic was difficult to accept. Actually, I still don’t accept it and I never will. We always ask ourselves: why me, etc.

(Young person 11) I sometimes tell myself: why me? Why am I the one with the illness and not someone else? Why does this illness exist?

Being responsible for the illness and its treatment

While self-care tasks do not change in adulthood, young people realize that they must become autonomous to manage their illness. The observation of their parents’ care procedures was identified as a main source of learning. As these young people grow up, parents transfer self-care skills to their children progressively. Some interviewees expressed the need to feel more confident in order to take on such a responsibility.

(Young person 12) Until 13–14 my mother took care of my treatment. And from there, my mother made me more responsible by telling me to think about it too.

(Young person 1) I know how to prepare the injection for myself. But I can’t do the shot because I’m a little scared. So my mother injects it. I’m afraid of doing things wrong.

Some young people were also keen to know more about the illness. While they had procedural knowledge of the management of the illness and its treatments (knowledge shared with the parents), they sometimes lacked a deeper understanding of the illness and its treatments.

(Young person 2) I really want to understand, even the biological mechanisms and everything … It would interest me to know very exactly what happens and how it happens.

A new role as a patient

Certain young people said that, while they were required to have greater autonomy in the way they managed their illness as they grew up, they did not always feel more autonomous when it came to medical decision-making. In those cases, young people felt like they were passively enduring their care and that their opinions were not taken into account, when they actually felt capable of participating in decisions (planning the transition, deciding on the number of necessary consultations, etc). However, young people need to acquire sufficient knowledge about how a usual consultation happens in adult care, their rights, the health care system, etc to have a more active role in the relationship with medical staff.

(Young person 3) The dietitians are super strict, so I don’t actually ask them how to adapt my food habits. Because if I listen to them, I don’t eat anything.

(Young person 17) I prefer it in the adults (service). It’s more mature. There are more people my age. I’m left alone more, too.

(Patient 7) After seeing the adult care for my first consultation, I said to myself that I would have liked to be prepared to this new type of consultation.

Theme 2: learning a new lifestyle

The young people being interviewed were encountering new situations, and they did not always feel like they were presented with the right information to make decisions based on their pathologies. Some of these situations included fatigue, health-risk behaviors (smoking, alcohol, drugs), stress, and sexuality. Although young people were sometimes aware of the general recommendations linked to their conditions, they did not always understand the reasons behind such recommendations.

(Young person 3) I know that it’s not good to smoke when you have diabetes, but I don’t see the connection.

Similarly, they expressed interrogations regarding new experiences (fatigue, stress), as they could not tell whether these sensations were linked to their illness, to their lifestyle, or to their own personal development.

(Young person 8) I’m often tired, but I don’t know why. I don’t know if it’s because of my illness or not.

(Young person 6) I never understand if drinking alcohol can lower blood sugar levels.

It seemed difficult for these young people to discuss these situations with caregivers since such conversations did not fit within the strict framework of the medical exam. It is important that the caregivers initiate a discussion on these topics.

(Young person 10) It’s hard to talk about sexuality with someone we don’t know very well or that we see as being “higher up” (talking about the health care staff), a little bit like parents. If we’re given documents first, it goes a lot better.

(Young person 13) We never talked about all of that (sexuality, alcohol, etc) with the health care staff.

Theme 3: learning a new health care service

According to young people who were consulted, moving to adult care did not automatically imply feelings of stress or anxiety, nor did it necessarily lead to sadness upon leaving pediatric care and its caregivers. It was not necessarily a time of questioning either. The transfer from pediatric to adult care could therefore be perceived as a normal event that was to be expected.

(Young person 2) Moving to the adult care isn’t going to change anything at all.

(Young person 11) The transition isn’t going to change anything in my life.

(Young person 12) I didn’t have the impression that it was hard to pass to the adults’ (service). For me, it was in the continuation.

Young people were, however, sensitive to their parents’ fears of losing quality health care and relational ties in pediatric care.

(Young person 12) For me, the transition is a small change. But for my mother, it’s a big change.

Before the transfer and before discovering adult care, young people are sometimes unaware of the changes that will occur in their health care. Findings showed (from “post-transfer” young people) that feelings of stress could emerge once young people had experienced the adult care environment (shorter consultations, different ways of making appointments, etc).

(Young person 9) I don’t feel as close to the doctors now that I’m with the adults. There are fewer exchanges. I don’t feel as confident with a doctor in adult care: since he doesn’t know me as well, I’m more afraid of his choices. Afraid that he’ll take things lightly and make a mistake.

Administrative procedures (being reimbursed for treatments, dealing with social security, etc) could also be perceived by young people as complicated to manage.

(Young person 7) It would be nice if there was a training session for young adults to help them manage the papers that need to be filled out, handed in … health insurance… explain how to manage those papers. Managing the medicine, that’s well explained, but not the papers …

Theme 4: maintaining a dual relationship with pediatric and adult care

According to certain young people, maintaining a relationship with pediatric caregivers for a specific amount of time while the adult care was first being explored allowed them to experience a “true” progressive transition process instead of a simple transfer. Young people sometimes engaged in this type of behavior informally by continuing to talk (by phone) to the pediatric doctor for questions they considered urgent, personal, or important. Since the relationship with the doctor in adult care was still new, trust had not yet been fully established. Young people could therefore prefer to ask certain questions to their pediatric doctors at first. This makes the change more secure for young people.

(Young person 9) I’ve continued to contact staff from pediatrics since I’ve been in adult (care). I know that if I have questions I better talk to a doctor in pediatrics.

(Young person 14) I think that I’ll continue to contact the pediatrics health care staff during my first weeks/months in adult (care).

(Young person 16) I know that if I need to one day, I can call my pediatrics care team.

Theme 5: encouraging exchanges with peers

Some young people expressed the fact that talking to other young people with chronic conditions could help them. It allowed them to move forward when learning to live with the illness, whether to manage self-care tasks or to understand the psychosocial dimension of the illness. Peers can become a resource for young people when the relationship with caregivers is difficult. Young people find support in peers who have lived through similar experiences and who can share self-care strategies or tips on adapting, all of which are perceived as useful and effective.

(Young person 3) I understood that I could eat other things because I went to a camp for young diabetic patients. I met other young people… And sharing experiences – that helped me. They were the ones who taught me that I could eat differently. Because the dietitians, they’re not very cool.

(Young person 11) The camps help a lot. We had lots of training sessions on smoking, alcohol, drugs, eating habits, physical activity … We also talked with others who also have diabetes, we talked about how we did…

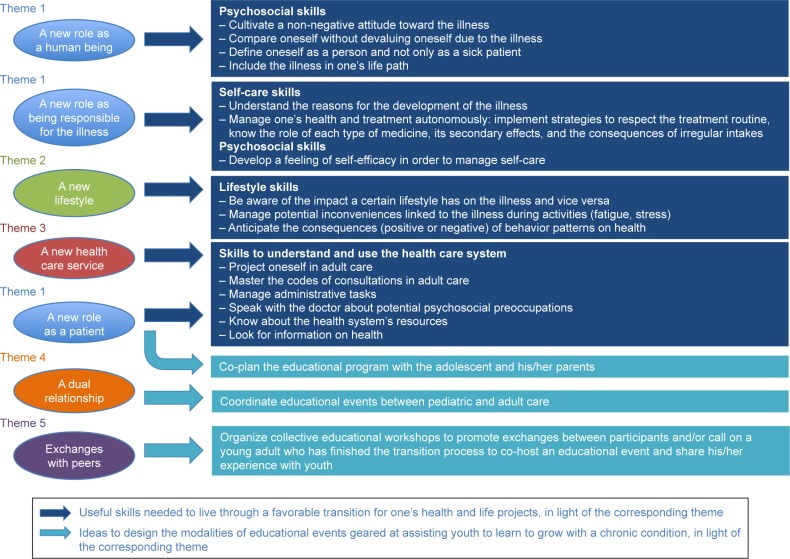

Proposed generic transition-oriented patient education

We identified the skills that could be introduced in transition-oriented patient education based on the educational needs that had been determined in the thematic analysis (Figure 1). Such a deduction was interpretive. It was meant to establish the elements that we had identified in the thematic analysis as skills that would be useful for young people to acquire to experience a favorable transition. The categories of skills refer back to the categories of needs identified in the literature, the latter of which served to guide our interviews (self-care, lifestyle management, psychosocial skills). An additional category emerged: understanding and using the health care system. Certain elements of the literature were specified (eg, the learning of self-care skills and lifestyle skills) and new elements were highlighted (eg, the educational needs felt by young people to manage their identity with an illness, the need for young people to learn to understand and use the health care system and to construct new roles as patients). Through the thematic analysis, we were also able to identify young people’s preferred ways of acquiring these skills, which they expressed during the interviews. These preferences can provide perspectives for professionals when designing the modalities of educational events that assist young people as the latter learn to grow with chronic conditions during their transition. We present this approach in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed approach for generic transition-oriented patient education.

It is important to note that young people who are the same age do not all have the same levels for each skill. This depends on their levels of development, their experience, etc. A personalized educational pathway must therefore be developed (with the young person and his parents). Our approach is progressive and cannot be reduced to a one-shot intervention. The caregivers should evaluate the young people’s skills at different times of transition (eg, at the start of adolescence, closer to the event of the transfer, and in adult care). This would enable them to identify the young people’s high-priority educational needs and offer appropriate educational sessions. Depending on the skills involved, caregivers can use a range of different teaching techniques. For example, role plays can be used for the acquisition and enhancement of interrelated skills (the young person can take on the role of the doctor and lead the consultation); case studies can serve as a medium for decision-making (such as reacting to a health incident at a party); young people can create pictures or videos to discuss identity construction or their representations of the future. This generic approach should be used by both pediatric and adult care caregivers to help young people grow up with a chronic illness and progressively acquire the aforementioned skills.

Discussion

So far, patient education has been recommended to optimize transition. However, the skills that young people need to acquire are not well documented.1,15,17 Our qualitative study allowed us to explore the transition experience in a novel way: a learning process as perceived by young people themselves. We identified educational needs that were common to young people suffering from different illnesses and in different contexts of care, needs which were specific to transition. The five themes identified through the thematic analysis can serve to design an educational program in which transition is viewed as a process of learning about change, and which surpasses the single issue of changing health services. It is a key shift in perspective, since the current mechanisms in place are centered on the transfer from one service to another17,34,35 instead of focusing on the transition as a whole, as experienced by young people.

The interviews did indeed show that one of the major challenges during transition was that young people had to create a new role for themselves. The process of coping with one’s identity is highlighted by our study in a new way. For the first time, the ways in which patient education can help young people to cope with psychosocial development and identity construction are specified. On a personal level, the skills young people needed during this period related to building a self-concept in which the illness was given a balanced place. The interviews showed that young people who exhibited strong nonadherence behaviors were also the ones who expressed having more difficulties mastering this psychosocial skill. This is confirmed by studies of several authors in psychology36–38 showing that the more young people with chronic conditions define themselves as “sick”, the more they risk lowering their adherence to treatment or developing a high level of unhappiness. Our results complete such research and provide potential solutions to facilitate the process for young people to learn to embody a new role as human beings with chronic illnesses (cf skills in Figure 1). The development of a satisfactory identity for young people could be an explicit goal in patient education programs, given the importance of identity during the transition – as expressed by young people – and its impact on health behaviors.39 If patient education is limited to learning self-care skills or to acquiring knowledge about the transfer, it can be perceived by young people as a stig-matizing activity (learn to become a patient), and does not correspond to the developmental challenge young people experience. Transition-oriented patient education could help young people learn to change themselves. To our knowledge, our research is the first to offer operational objectives to achieve this.

The literature on transition highlights how important it is for young people to become more autonomous in self-care procedures and to build on their new role of being responsible for the illness.17 In this regard, we noticed that young people engaged in vicarious learning: they observed and analyzed their parent(s)’ care procedures in an effort to apply gradually these actions autonomously as they grew. They therefore do not automatically express a need for education nor do they view education interventions as a priority in this realm. On this topic, young people and parents seem to share the same opinion. In a review on the parent’s experience of transition, Heath et al40 showed that parents facilitate their child’s growing independence to manage self-care skills. However, the transfer of skills (in self-care procedures) from the parent to young people can be hindered in cases when parents are afraid of letting their child become autonomous in the management of their health. The health care team must therefore ensure that the transfer of skills does indeed take place, they must promote it or even dispense these skills themselves if needed. For that, they must include the parents in the transition process and define their role clearly.40 On the contrary, young people requested more information on general matters of health (at risk behaviors, sexuality) linked to their illnesses, which confirms the findings of previous studies.41,42 Young people are led to question themselves when faced with issues such as fatigue or stress, since they are unable to determine the impact their illness has on their experiences and whether a health care professional can help in these cases. These issues are common to all young people, since the latest Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children report showed that young people were increasingly preoccupied by questions related to mental and physical well-being.43 Our results reveal that young people do not seek caregivers as resources on these matters since such issues do not fit within the strict framework of the medical exam. Transition-oriented patient education is an opportunity to change this representation and empower young people to manage their global health instead of simply focusing on self-care linked to the illness. The acquisition of skills needed to live with a chronic condition cannot be reduced to a formal educational process. The young people’s family and health care environments, as well as the health system as a whole, contribute to the acquisition of such skills.12,44 Transition-oriented patient education must be designed systemically and must fit within an overall system that is patient centered. Our results show that formalizing a dual relationship would allow young people to feel secure and not to sever abruptly the connections made in pediatric care. Young people could gradually create a relationship with the new caregivers. This formalized system can benefit from joint consultations, the designation of a coordinating nurse,45 or the visit of adult facilities by adolescents in the pre-transfer phase.46

Caregivers and young people could co-decide on a time to end the dual relationship (based on a reasonable time frame). At a period when young people ask for more autonomy and responsibility, giving them a more proactive role in the transition process could reinforce the therapeutic relationship and the adherence to treatment. Similarly, as young people highlighted the progress they had made after having learned from peers, this peer system could be formal-ized within the transition process by setting up educational programs in which young people in the post-transfer phase could testify and talk about their experiences. Such examples of engagement from persons with chronic conditions are starting to take place within the health system. This comes as a response to the users’ increasing demand to be more involved in the care they receive and to be represented more satisfactorily.47–49

Limitations

Since this study was qualitative in nature, we were able to better understand and highlight certain phenomena specific to the transition period among young people. However, the proposals uncovered here must be read as hypotheses, which other studies will need to verify further. The diversity of our sample, while deliberately sought, may have limited us in gaining a deeper understanding of one group of young people in particular. It is likely that needs vary in intensity depending on the illness or on young people’s sociodemographic and/or psychological profiles. Similarly, our sampling did not include certain particular cases which we, in turn, did not address. For example, when a rare disease in pediatrics becomes a prevalent disease in adult care, as is the case for certain chronic inflammatory diseases, what are the specific requirements needed to prepare young people for this reality? Furthermore, information related to study refusals by young people should have been better collected to assess potential sample bias. Finally, the analytical framework used for the interviews was limited to an educational reading of the phenomena at hand. Although we aimed to pay attention to the “off-topic” elements that seemed meaningful to young people, our questioning approach may have led us to miss certain topics which would not have been spontaneously mentioned by the participants, given our interview model.

Conclusion

To answer the needs of young people, transition-oriented patient education could consist of education focused on change. Young people are led to take on a new role (they become responsible for their own health and are accountable as human beings), they make decisions regarding new lifestyles (emotional and sexual life, smoking, alcohol, etc), and they use a new health care service. In order to succeed, young people must enlist skills related to self-care, lifestyle management, psychosocial elements, and an understanding of the health care system. Although our results could be completed by the needs identified by the caregivers to improve the autonomy of young people, this study provides a generic framework for educational programs which could be implemented regardless of young people’s specific diseases and health care contexts. It seems like a transition process could be formalized, one which would take the young people’s situation into account and would engage both pediatric care and adult care. The transition can, finally, be viewed as an opportunity for young people to participate and engage in the health care system more easily.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the young people who agreed to participate in this research, as well as the institutional partners and health professionals for their collaboration.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Fegran L, Hall EO, Uhrenfeldt L, Aagaard H, Ludvigsen MS. Adolescents’ and young adults’ transition experiences when transferring from paediatric to adult care: a qualitative metasynthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(1):123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson AR. Non-compliance and transfer from paediatric to adult transplant unit. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(6):0469–0472. doi: 10.1007/s004670050794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pacaud D, Yale JF. Exploring a black hole: transition from paediatric to adult care services for youth with diabetes. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;10(1):31–34. doi: 10.1093/pch/10.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferro MA. Adolescents and young adults with physical illness: a comparative study of psychological distress. Acta Paediatr. 2013;103:32–37. doi: 10.1111/apa.12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . The Second Decade: Improving Adolescent Health and Development. Geneva: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farre A, Wood V, Rapley T, Parr JR, Reape D, McDonagh JE. Developmentally appropriate healthcare for young people: a scoping study. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(2):144–151. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonagh JE, Farre A, Gleeson H, et al. Transition Collaborative Group Making healthcare work for young people. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(6):623. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell F, Biggs K, Aldiss SK, et al. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD009794. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009794.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blum RW, Garell D, Hodgman CH, et al. Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1993;14(7):570–576. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90143-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(6):548–553. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.202473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization . Therapeutic Patient Education: Continuous Education Programmes for Health Care Providers in the Field of Prevention of Chronic Diseases. WHO Working Group recommendations. Copenhagen. Regional Office for Europe, WHO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz LA, Tuchman LK, Hobbie WL, Ginsberg JP. A social-ecological model of readiness for transition to adult-oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(6):883–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed-Knight B, Blount RL, Gilleland J. The transition of health care responsibility from parents to youth diagnosed with chronic illness: a developmental system perspective. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(2):219–234. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modi AC, Pai AL, Hommel KA, et al. Pediatric self-management: a framework for research, practice, and policy. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):e473–e485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt S, Herrmann-Garitz C, Bomba F, Thyen U. A multicenter prospective quasi-experimental study on the impact of a transition-oriented generic patient education program on health service participation and quality of life in adolescents and young adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(3):421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt S, Markwart H, Bomba F, et al. Differential effect of a patient-education transition intervention in adolescents with IBD vs. diabetes. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(4):497–505. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-3080-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morsa M, Gagnayre R, Deccache C, Lombrail P. Factors influencing the transition from pediatric to adult care: a scoping review of the literature to conceptualize a relevant education program. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(10):1796–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rich M, Ginsburg KR. The reason and rhyme of qualitative research: why, when, and how to use qualitative methods in the study of adolescent health. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(6):371–378. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(6996):42–45. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6996.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirk S. Methodological and ethical issues in conducting qualitative research with children and young people: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(7):1250–1260. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zarotti N, Simpson J, Fletcher I. ‘I have a feeling I can’t speak to anybody’: A thematic analysis of communication perspectives in people with Huntington’s disease. Chronic Illn. 2017 Jan 1; doi: 10.1177/1742395317733793. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Réach G, Fompeyrine D, Mularski C. Understanding the patient multidimensional experience: a qualitative study on coping in hospitals of Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:555–560. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S78228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell LE, Bartosh SM, Davis CL. Adolescent transition to adult care in solid organ transplantation: a consensus conference report. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2230–2242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Court JM, Cameron FJ, Berg-Kelly K, Swift PGF. ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2006–2007. Diabetes in adolescence. Pediatric Diabetes. 2008;9:255–262. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawyer SM, Drew S, Yeo MS, Britto MT. Adolescents with a chronic condition: challenges living, challenges treating. Lancet. 2007;369(9571):1481–1489. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60370-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deccache A. Teaching, training or educating patients? Influence of contexts and models of education and care on practice in patient education. Patient Educ Couns. 1995;26(1–3):119–129. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00728-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.EURORDIS, Rare Diseases Europe About rare diseases. [Accessed July 18, 2018]. Available from: https://www.eurordis.org/about-rare-diseases.

- 28.Morse JM. Strategies for sampling. In: Morse JM, editor. Qualitative Nursing Research: A Contemporary Dialogue. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the Trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson J, Elkan R. Health Needs Assessment. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2016;27:591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clemente D, Leon L, Foster H, Carmona L, Minden K. Transitional care for rheumatic conditions in Europe: current clinical practice and available resources. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12969-017-0179-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Roux E, Mellerio H, Guilmin-Crépon S, et al. Methodology used in comparative studies assessing programmes of transition from paediatrics to adult care programmes: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e012338. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helgeson VS, Novak SA. Illness centrality and well-being among male and female early adolescents with diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(3):260–272. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luyckx K, Seiffge-Krenke I, Schwartz SJ, et al. Identity development, coping, and adjustment in emerging adults with a chronic illness: the sample case of type 1 diabetes. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(5):451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferro MA, Boyle MH. Self-concept among youth with a chronic illness: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol. 2013;32(8):839–848. doi: 10.1037/a0031861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz SJ, Petrova M. Fostering healthy identity development in adolescence. Nat Hum Behav. 2018;2(2):110–111. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heath G, Farre A, Shaw K. Parenting a child with chronic illness as they transition into adulthood: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of parents’ experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):76–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandes SM, O’Sullivan-Oliveira J, Landzberg MJ, et al. Transition and transfer of adolescents and young adults with pediatric onset chronic disease: the patient and parent perspective. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2014;7(1):43–51. doi: 10.3233/PRM-140269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Staa A, Sattoe JN. Young adults’ experiences and satisfaction with the transfer of care. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55(6):796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO Growing up unequal: gender and socioeconomic differences in young people’s health and well-being. Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2013/2014 survey. [Accessed July 4, 2018]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/303438/HSBC-No.7-Growing-up-unequal-Full-Report.pdf?ua=1.

- 44.Walsh JM, McPhee SJ. A systems model of clinical preventive care: an analysis of factors influencing patient and physician. Health Educ Q. 1992;19(2):157–175. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suris JC, Dominé F, Akré C. La transition des soins pédiatriques aux soins adultes des adolescents souffrant d’affections chroniques [The transition from pediatric care to adult care of adolescents suffering from chronic conditions] Rev Med Suisse. 2008;161:1441–1444. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malivoir S, Courtillot C, Bachelot A, Chakhtoura Z, Téjédor I, Touraine P. Un programme d’éducation thérapeutique centré sur la transition des patients, avec endocrinopathie chronique, entre les services d’endocrinologie pédiatrique et adulte [A therapeutic education program centered on the transition of patients with chronic endo-crinopathy, from pediatric to adult endocrinology services] Presse Med. 2016;45(5):e119–e129. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2015.10.025. French. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pomey MP, Hihat H, Khalifa M, Lebel P, Néron A. Patient partnership in quality improvement of healthcare services: patients inputs and challenges faced. Patient Exp J. 2015;2:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karazivan P, Dumez V, Flora L, et al. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: a conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):437–441. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ambresin AE, Bennett K, Patton GC, Sanci LA, Sawyer SM. Assessment of youth-friendly health care: a systematic review of indicators drawn from young people’s perspectives. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(6):670–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]