Abstract

Objectives:

Bipolar disorder is associated with a high risk of suicide attempts and suicide death. The main objective of this paper was to identify and quantify the demographic and clinical correlates of attempted and completed suicide in people with bipolar disorder.

Methods:

Within the framework of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Suicide, a systematic review of articles published since 1980 characterized by both key terms bipolar disorder and ‘suicide attempts or suicide’ was conducted, and data extracted for analysis from all eligible articles. Demographic and clinical variables for which ≥ 3 studies with usable data were available were meta-analyzed using fixed or random-effects models for association with suicide attempts and suicide deaths. There was considerable heterogeneity in the methods employed by included studies.

Results:

Variables significantly associated with suicide attempts were: female sex, younger age of illness onset, depressive polarity of first illness episode, depressive polarity of current or most recent episode, comorbid anxiety disorder, any comorbid substance use disorder, alcohol use disorder, any illicit substance use, comorbid cluster B/borderline personality disorder, and first-degree family history of suicide. Suicide deaths were significantly associated with male sex and first-degree family history of suicide.

Conclusions:

This paper reports on the presence and magnitude of the correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in bipolar disorder. These findings do not address causation, and the heterogeneity of data sources should limit the direct clinical ranking of correlates. Our results nonetheless support the notion of incorporating diagnosis-specific data in the development of models of understanding suicide in bipolar disorder.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, meta-analysis, suicide

Mental illness is present in nearly all people who attempt or die by suicide, and among psychiatric diagnoses, bipolar disorder (BD) may be associated with the highest suicide risk (1–14). Among people with BD, the estimated rate of death by suicide is 0.2–0.4 per 100 person-years (5, 15–17), however these rates may reflect data from higher risk periods of time in the life of someone with BD, and simple extrapolation to estimates of lifetime risk are inherently unreliable. The absolute risk of suicide among patients with a diagnosis of BD at first hospital contact has been found to be around 8% for men and 5% for women over a median of 18 years follow-up (12), and the standardized mortality ratio of BD suicide deaths compared to the general population has been reported to be 10–30-fold (18–21). Rates of suicide attempts are also very high, with an estimated annual risk of 0.9% per year, and a lifetime risk of up to one-half of sufferers with BD (22–25).

There are a number of well-described correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths identified in the broader mental illness or public health literature, including sex, depression, anxiety, substance use, family history of suicide, and others (26–28). Suicide is a behavioral endpoint that results from a multitude of factors, and confirming whether these broadly identified correlates of risk of suicide attempts and suicide are also present in BD populations is imperative. Analogous investigation of BD-specific clinical factors such as illness subtype and polarity of first and most recent episode is also warranted. These type of data would inform the emerging effort to move towards more diagnosis-specific approaches to understanding suicide risk, risk assessments, and prevention (29–33).

Recently published reviews on suicide attempts and suicide in BD shed light on the scope of the public health, clinical assessment and management challenges, and also illuminate glaring gaps in the available data (18, 29, 30, 34–37). One such gap is the absence of up to date, quantitative, meta-analytic models of the specific demographic and clinical factors putatively associated with suicide attempts and suicide in BD. While individual studies can identify correlates within a specific study population, these findings require both replication and an estimate of the magnitude of the association in order to inform risk assessments and suggest avenues for prevention. Prior meta-analyses by Hawton et al. (38) and Novick et al. (39) laid the foundation for this approach in BD, however, a major expansion of data has since occurred in the past few years, which is not captured in these earlier publications. This is especially relevant for suicide deaths, which have now been more thoroughly examined in several large epidemiological BD samples (4, 8, 12, 15, 40).

The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) is a leading organization devoted to promoting international collaboration in the study of BD. Under the auspices of the ISBD, a Task Force on Suicide comprised of 20 international experts was launched, with the objectives of completing a comprehensive review of the available literature and conducting meta-analyses on putative correlates of suicide attempts and suicide in BD. This publication is the product of the work done by this task force to achieve the goal of identifying and quantifying the degree of associations between demographic and clinical variables with the risk of suicide attempts and suicide death in people with BD.

Methods

Study search and selection

We conducted a systematic review of English-language articles using keywords bipolar disorder and ‘suicide attempts’ or ‘suicide’ published between January 1, 1980 and June 30, 2013. The search was then expanded via the ancestry approach by manual examination of reference lists of included articles and recent published reviews on suicide or suicide attempts in BD (18, 29, 30, 34–37). Included articles had to have met all the following criteria: (i) subjects with BD comprised all or a large majority (> 80%) of the study population; (ii) study population was exclusively > 13-years-old; (iii) a binary measure of suicide attempts or suicide deaths was reported; (iv) a non-suicide attempt or non-suicide group was included; and (v) a binary measure of a demographic or clinical variable of interest was reported or could be calculated from the published data. Age of onset was included as a continuous variable, since there was no uniform definition of early or later age of onset used across studies. Both prospective and retrospective studies were included, as were studies from either clinical or epidemiological samples. There is no uniform definition of a suicide attempt in relation to intent or lethality, however studies were excluded if they only reported on non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation or if suicidality ratings were reported as a continuous measure.

Data extraction

Using the PRISMA framework for systematic reviews (41), the initial search yielded 1,700 abstracts. These were screened for eligibility criteria and duplication of samples, resulting in 74 full-text articles being assessed by two trained investigators (AS and CR) who reviewed each article for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles with any uncertainty about eligibility were discussed and a decision made through consensus. Studies were excluded at this stage if they contained subject overlap with another article or did not report sufficient details for data analysis (n = 33 studies excluded). This resulted in an initial group of 41 eligible studies, including one in which corresponding author was contacted for clarification (one study). Whenever possible, task force members, as a geographically diverse group of experts who were authors on many of the included studies, provided additional details of data when insufficient information was available in the published article (additional three studies). This resulted in a total of 44 eligible studies.

In total, 34 papers reported on suicide attempts (total N = 50,004 subjects with BD) across one or more variables, with 31/34 using clinical samples, 29/34 using non-representative samples, and 30/34 reporting suicide attempts in a retrospective manner. There were 12 papers that reported on suicide deaths (total N = 75,137 subjects with BD), with 8/12 using clinical samples, 4/12 using non-representative samples, and 8/12 identifying suicide in a retrospective sample. Only two studies reported on both suicide attempts and deaths (15, 40).

For each article, the following data were extracted and coded: (i) author name(s); (ii) year of publication; (iii) number of subjects with or without a suicide attempt for each demographic and clinical variable of interest; and (iv) number of suicide deaths or non-deaths for each demographic and clinical variable of interest. No study included all variables of interest, so data were only extracted for those variables examined in the publication. Variables of interest were chosen based on the general and BD-specific literature on suicide attempts and deaths, and included: (i) sex; (ii) age of onset of BD; (iii) subtype of BD [bipolar I disorder (BD-I) or bipolar II disorder (BD-II)]; (iv) polarity of first mood episode; (v) polarity of current or most recent mood episode (mixed episodes were generally reported as a subset of mania, and there was insufficient data to specifically analyze mixed episodes); (vi) lifetime history of past suicide attempts (for analysis of suicide deaths only); (vii) current or lifetime anxiety disorder; (viii) presence of lifetime history of psychotic symptoms; (ix) current or lifetime substance use disorder (most studies reported as either abuse, dependence, or both), as well as the following three subcategories: (xA) current or lifetime alcohol use disorder; (xB) current or lifetime cannabis use; and (xC) any current or lifetime illicit substance use disorder; (xi) current or lifetime personality disorder; and (xii) first-degree family history of death by suicide.

Data analysis

Cochrane Information Management System–Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.2 (November 2012) was utilized to conduct the meta-analyses. For each variable of interest, a meta-analysis was only conducted if there was a minimum of three studies with usable data. A total of 13 variables had sufficient data for analysis on suicide attempts (all except past suicide attempts) and four variables had sufficient data for analysis on suicide. The same study could yield data for multiple analyses, as many studies reported on more than one variable of interest. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for all binary measures and weighted mean difference was calculated for age of illness onset, the only continuous measure. Random-effects models were conducted when significant heterogeneity was present (Cochrane test p < 0.1); otherwise fixed-effects models were conducted. As a sensitivity analysis on the effect of very large studies, we re-ran meta-analyses removing any single study that had a > 40% weighting.

A meta-regression was conducted (STATA software) with suicide attempts in males versus females as the meta-analytic outcome variable, and covariates included based on a sufficient number of observations within studies that reported on sex-differences. Covariates included polarity of first mood episode, mean age of illness onset, BD subtype, psychosis, any substance use disorder, alcohol or illicit substance use disorder, and family history of suicide. Tests of meta-bias (effect of small studies) and meta-influence (influence of a single study) were also conducted. Other meta-regressions could not be completed due to an insufficient number of observations.

Results

Findings related to suicide attempts

Thirty-four papers reported suicide attempts across one or more variables in a manner suitable for meta-analysis, with a total of 50,004 subjects with BD included in the non-overlapping samples. (15, 24, 40, 42–72). We examined 13 variables, including sex, age of illness onset, BD subtype (BD-I or BD-II), polarity of first mood episode, polarity of current or most recent mood episode, lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder, lifetime history of psychotic symptoms, any substance use disorder, alcohol use disorder, cannabis use, any illicit substance use disorder, comorbid cluster B/borderline personality disorder, and first-degree family history of suicide. Each of Figures 1–9 and Supplementary Figures S1–S3 shows the results of the meta-analysis for the specific variable(s) of interest.

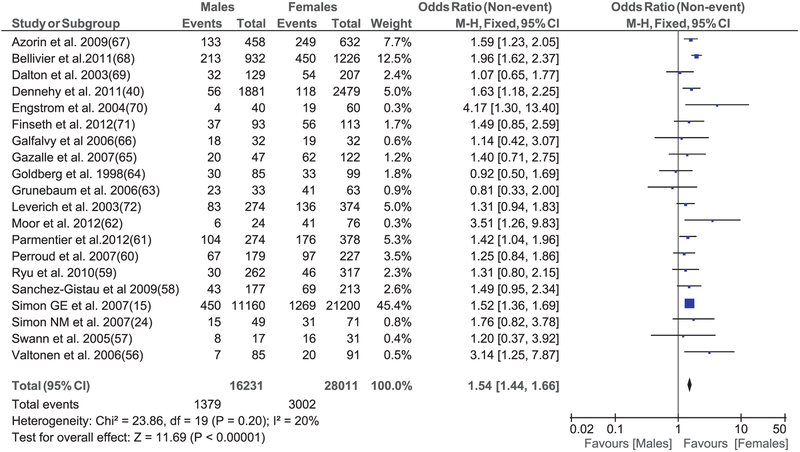

Fig. 1.

Meta-analysis of suicide attempts among males and females with bipolar disorder. CI = confidence interval.

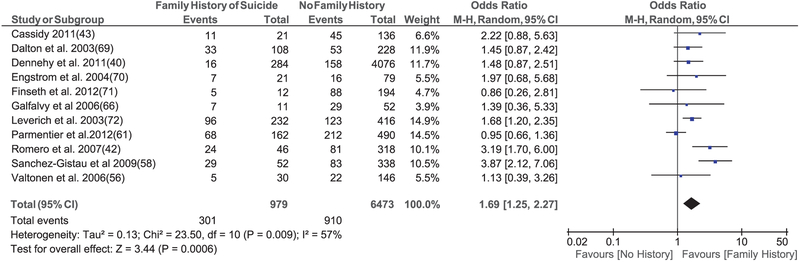

Fig. 9.

Meta-analysis of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder based on the presence of a family history of suicide. CI = confidence interval.

Numerous variables were found to be significantly correlated with presence of suicide attempts. Women were significantly more likely to attempt suicide (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.44–1.66, p < 0.00001), with 8/20 studies reporting a significant effect in this direction, and the remaining 12/20 studies reporting no significant sex-based difference (Fig. 1). A meta-regression conducted with sex-differences in suicide attempts as the meta-analytic outcome found no significant independent association for any other tested covariate. There were also no significant small study or single study effects.

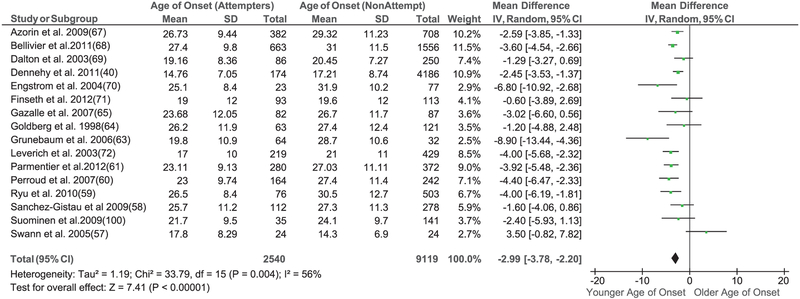

Age of illness onset was 2.99 years younger (95% CI: 2.20–3.78 years, p < 0.00001) among those with a history of suicide attempt (Fig. 2), with a standardized mean difference of −0.29 (95% CI: −0.36 to −0.21, p < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of suicide attempts based on age of onset of bipolar disorder. SD = standard deviation; CI = confidence interval.

BD subtypes, BD-I or BD-II, were examined in 14 relatively evenly weighted studies, with two studies finding higher rates of suicide attempt in BD-I, two studies finding a higher rate in BD-II, and the remainder finding no difference, resulting in no overall effect of subtype being identified (OR = 1.07, 95% CI: 0.79–1.45, p = 0.68) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

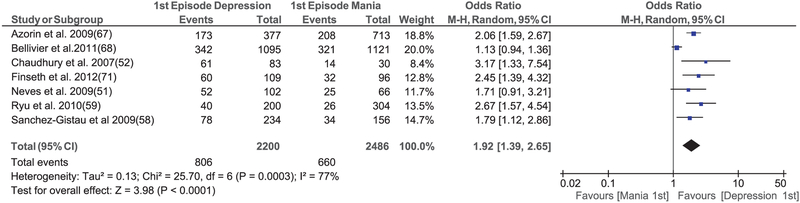

Subjects with a depressive polarity of first mood episode were nearly twice as likely to attempt suicide (OR = 1.92, 95% CI: 1.39–2.65, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3), with all seven studies reporting a similar direction of effect, and most reaching statistical significance.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of suicide attempts based on polarity of first episode of bipolar disorder. BD-I = bipolar I disorder; BD-II = bipolar II disorder; CI = confidence interval.

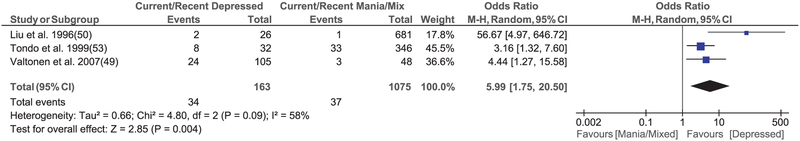

Depressive polarity of the current or most recent mood episode had the strongest association with a suicide attempt (OR = 5.99, 95% CI = 1.75–20.5, p = 0.004), but only three studies reported on this variable, resulting in wide confidence intervals (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of suicide attempts based on polarity of current or most recent episode of bipolar disorder. CI = confidence interval.

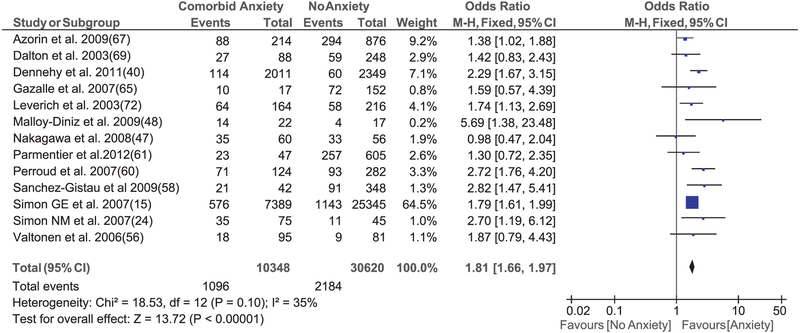

The presence of a lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder was significantly associated with suicide attempts in 8/13 studies, with an OR of 1.81 (95% CI: 1.66–1.97, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5). Although one study had a very large weighting in this analysis, there was a consistent direction of effect with the other studies.

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder based on the presence of comorbid anxiety disorder. CI = confidence interval.

Of the seven studies that examined history of psychosis, one reported a higher rate of suicide attempt among subjects with a history of psychosis, one reported a higher rate among subjects without psychosis, and the remainder found no significant difference, resulting in no significant association being identified (OR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.64–1.30, p = 0.61) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

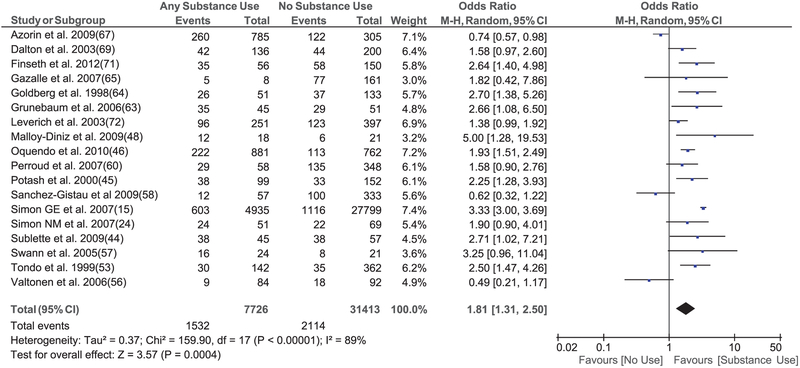

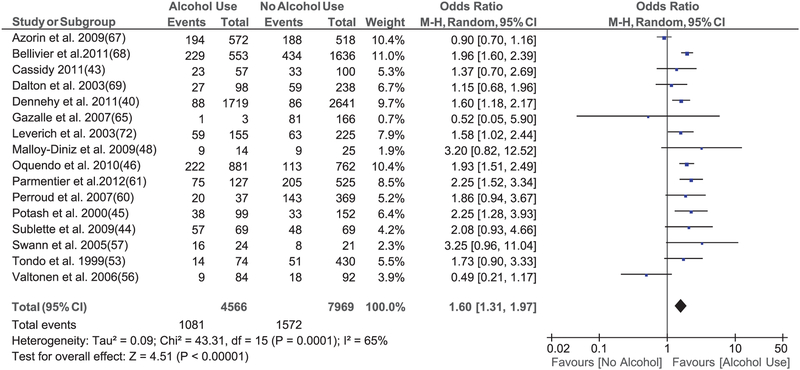

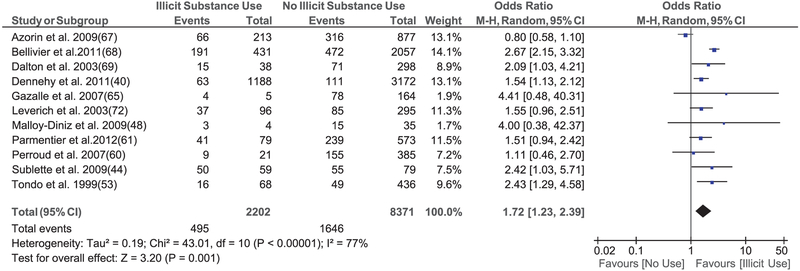

The presence of a current or lifetime comorbid substance use disorder was separated into 4 non-mutually exclusive groups, including (i) any substance use disorder (OR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.31–2.50, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 6); (ii) alcohol use disorder (OR = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.31–1.97, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 7A); (iii) any cannabis use (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 0.85–1.94, p = 0.23) (Supplementary Fig. S3); and (iv) any illicit substance use disorder (OR = 1.72, 95% CI: 1.23–2.39, p = 0.001) (Fig. 7B). Each of these substance use variables, except cannabis use, was significantly associated with suicide attempts.

Fig. 6.

Meta-analysis of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder based on the presence of any substance use disorder. CI = confidence interval.

Fig. 7.

Meta-analyses of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder based on the presence of alcohol use disorder or any illicit substance use disorder. CI = confidence interval.

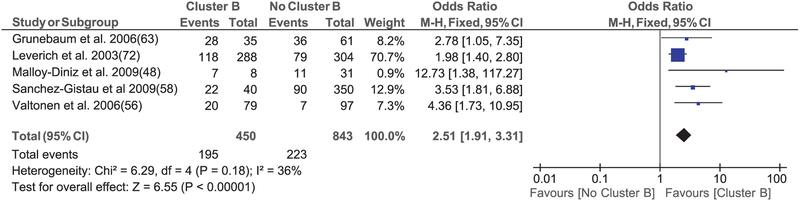

Comorbid cluster B/borderline personality disorder was strongly associated with suicide attempts in all 5/5 studies, resulting in an OR of 2.51 (95% CI: 1.91–3.31, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 8). Data on other personality disorders or traits were not available in a sufficient number of studies to permit meta-analysis.

Fig. 8.

Meta-analysis of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder based on the presence of a comorbid cluster B/borderline personality disorder. CI = confidence interval.

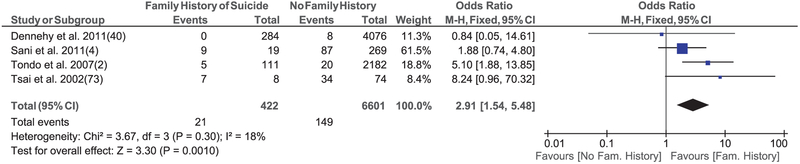

Finally, a first-degree family history of death by suicide was found to be associated with suicide attempts in all 11 studies, among a total of 7,452 subjects with BD (OR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.25–2.27, p = 0.0006) (Fig. 9).

Findings related to suicide deaths

Twelve studies on completed suicide were available (2, 4, 8, 12, 15, 21, 40, 73–77). We could examine four variables: sex, lifetime history of psychotic symptoms, any substance use disorder, and first-degree family history of suicide. Despite the smaller number of studies, a total of 75,137 subjects with BD were included in these analyses, mostly comprised of several large US and European cohort studies (8, 12, 15, 40).

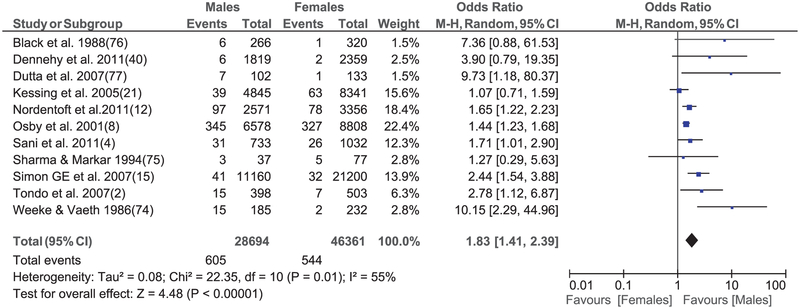

The sex-based analysis from 11 studies included a large sample size of 75,055 subjects with BD and a total of 1,149 suicide deaths. Suicide deaths were significantly associated with male sex (OR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.41–2.39, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 10), with each study reporting an effect in the same direction, most at a significant level.

Fig. 10.

Meta-analysis of suicide deaths among males and females with bipolar disorder. CI = confidence interval.

Similar to the data for suicide attempts, a history of psychosis had no significant association with suicide deaths (OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.50–1.74, p = 0.82) (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, in contrast to the finding for suicide attempts, the presence of any substance use disorder was not significantly associated with suicide deaths (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 0.93–1.56, p = 0.17) (Supplementary Fig. S5), with 3/4 individual studies finding no significant association.

Only four studies reported on first-degree family history of suicide, but nonetheless a significant association was found (OR = 2.91, 95% CI: 1.54–5.48, p = 0.001) (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Meta-analysis of suicide deaths in bipolar disorder based on the presence of a family history of suicide. BD = bipolar disorder; CI = confidence interval.

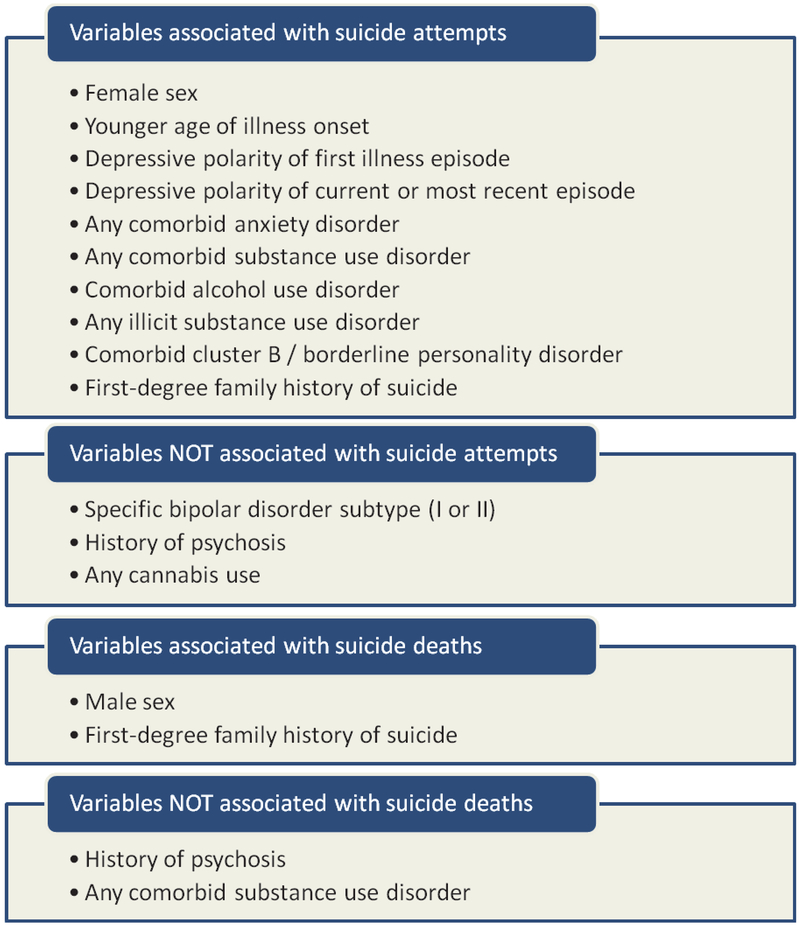

Figure 12 provides a list of variables that were or were not associated with suicide attempts or suicide in people with BD.

Fig. 12.

List of variables that were or were not associated with suicide attempts or suicide deaths in people with bipolar disorder based on meta-analytic results. *Could not be ranked because a continuous measure of age of illness onset was used.

Sensitivity analyses for effect of very large studies found no switch from variables being significant to non-significant, or vice versa. Furthermore, using random effect analyses even for variables with non-significant heterogeneity resulted in only very minor changes to ORs and modest widening of CIs, with the exception being the association between presence of any substance use disorder and suicide deaths, which increased to OR = 1.49 (95% CI = 0.88–2.55).

Discussion

This paper reports on a comprehensive set of meta-analyses conducted to identify and quantify the correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in BD populations. It was undertaken as part of the work of the ISBD Task Force on Suicide—an international collaborative effort to study suicide in BD. There have been prior meta-analyses published on BD subtype and suicide attempts (39), and on a broader examination of demographic and clinical correlates of suicide attempts and suicide in BD, but this latter work by Hawton et al. (38) was published in 2005, and therefore did not include the large number of studies published in the last decade. Our results are noteworthy in reporting on a number of general and BD-specific variables that are relevant for understanding risk of suicide attempts and suicide specific to a population with BD. Quantifying the associations permits ranking of correlates and informs risk estimates in a more meaningful way.

Of the variables for which sufficient data were available to conduct meta-analyses, 10 out of 13 were significantly associated with suicide attempts, and two out of four were significantly associated with suicide deaths. Factors significantly associated with suicide attempts were (ranked from highest to lowest ORs): depressive polarity of current or recent episode (OR = 5.99), comorbid cluster B/borderline personality disorder (OR = 2.51), depressive polarity of first illness episode (OR = 1.92), comorbid anxiety disorder (OR = 1.81), any substance use disorder (OR = 1.81), any illicit substance use (OR = 1.72), first-degree family history of suicide (OR = 1.69), alcohol use disorder (OR = 1.60), and female sex (OR = 1.54). Earlier age of illness onset was also significantly associated with suicide attempts (mean difference 2.99 years, OR = 1.69).

The evidence for both depressive polarity of current/most recent episode and first mood episode each being correlated with suicide attempts was generated from clinical samples. Mixed symptoms have previously been associated with elevated risk for suicide attempts (29, 64), but rates of mixed episodes were low in the studies we analyzed, and were most often classified together with manic episodes. Recent evidence suggests that broadly defined mixed states may be associated with the highest risk of suicide attempts per time period spent in a specific phase of illness (78), and with the new broader definition of mixed states in DSM-5, future studies should be able to examine more accurately the impact of mixed symptoms on suicide risk, whether during a manic or depressive phase. Nonetheless, our analyses identified current or most recent depressive episode as the strongest correlate of suicide attempts, likely as a result of a combination of elevated risk per time period, as well as the predominance of the depressive phase of illness in the natural course of BD.

The comorbidity between cluster B/borderline personality disorder and BD has long been a source of diagnostic complexity, requiring comprehensive etiological and management considerations (79). Our data identified that elevated risk of suicide attempt (OR = 2.51) is another important factor to consider, with all 5 studies demonstrating a strong association. It is possible that having recurrent suicidal behavior or self-harm without intent to die as part of the diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder may have resulted in an inflation of the association, and we could not address this issue in the available data, however other cluster B personality disorders do not include this criterion, and as such it is unlikely to fully account for the identified association.

The finding of comorbid anxiety being significantly associated with suicide attempts was highly consistent across studies. A majority of people with BD will experience a comorbid anxiety disorder at some point in their lives (24, 80), thus elevated rates of suicide attempts are highly clinically relevant. There is some evidence that the association between anxiety and suicide attempts in BD may be partially mediated through increased rumination (24), as well as by comorbid cluster B personality disorders (47). Unfortunately, most studies do not report on the sequencing of the comorbid symptoms or disorders and the suicide attempt(s), which may or may not be confluent. It is therefore difficult to develop a clear attribution model without sufficient prospective data to elucidate the onset and timing of the comorbid anxiety in relation to the suicide attempt.

The association between suicide attempt and substance use disorders was of a similar magnitude to anxiety (both OR = 1.81), but the results for substance use were more variables across studies, with several showing a trend in the opposite direction. This led us to break down the substance use category into alcohol use disorder, any illicit drug use, and specific cannabis use. Significant associations were identified among studies of alcohol use disorder (OR = 1.60) and illicit drug use (OR = 1.72), but not for cannabis use (OR = 1.29). While the largest study of cannabis use did report a significant association with suicide attempts, the other three studies found no significant effect. In a recent review by Watkins and Meyer (81), preliminary evidence identified impulsivity as mediating the association between alcohol use and suicide attempts in BD, but whether this is true across substance use disorders is not known.

Female sex was associated with suicide attempts (OR = 1.54), but this was a weaker association than has most commonly been reported in non-BD samples (27, 82, 83), and only 8/20 studies in our analysis reported any significant sex-based association. Results of the meta-regression did not identify any significant covariates to this association, but there may be other diagnosis-specific factors such as a greater female preponderance for a more depression-prone course of bipolar illness (84, 85) that are additionally relevant. It is also worth noting that men with BD were underrepresented in the available trials, accounting for only 36.7% of all subjects in the studies that reported on suicide attempts. Given the lack of sex-based differences in prevalence of BD, this suggests an ascertainment or sampling bias may also be relevant when interpreting these results. Overall, the findings highlight the importance of a diagnostic-specific examination of correlates of suicide attempts such as sex, since extrapolation from a broader literature on sex-based differences may be inaccurate.

Earlier age of onset of BD was also significantly associated with a history of suicide attempts, with a mean difference of 2.99 years. Early onset of illness has consistently been shown to have negative prognostic implications (86, 87), and our data support this observation. It is worth noting that we only extracted data from reports of study populations exclusively > 13 years-of-age, and 27/32 sample groups for this analysis had a mean age of illness onset of ≥ 19 years, therefore our findings primarily relate to adult-onset BD.

There were three variables tested that were not significantly associated with suicide attempts. In contrast to the limited data on cannabis use, there were more studies on BD subtype (14 studies) and history of psychosis (seven studies). Considerable variability was present in the BD subtype studies, with ORs for BD-I varying from 2.38 to 0.27. There were over twice the number of subjects with BD-I compared to subjects with BD-II, which is not in line with the relative equal lifetime prevalence of the two subtypes (88), and again suggests that there may be a sample bias in the available literature. Nonetheless, analysis of current data suggests that subjects with BD-II are just as likely to attempt suicide as those with BD-I.

History of psychosis was examined in relation to both suicide attempts and suicide deaths, and neither analysis identified a significant association, although there was a wide confidence interval (0.50–1.74) in the suicide death analysis. It is important to note that studies identified a history of psychotic symptoms at any point in the course of illness, and did not focus on specific phases of illness. Given the strong correlation between current or recent depressive episode and suicide attempts, it is possible that a current or recent psychotic depression may be associated with suicide attempts or even suicide deaths, but this has not clearly been shown in other studies (89), and data was not available to test this hypothesis in BD.

Another challenge is that there are far fewer studies of correlates of suicide deaths in BD, as compared to suicide attempts. Suicide deaths are rarer and inherently more difficult to study, as evidenced by only four variables being sufficiently examined to allow for meta-analysis. In addition to psychosis, other variables tested included sex, any substance use disorder and first-degree family history of suicide. Men with BD were nearly twice as likely to die by suicide as compared to women with BD (OR = 1.83). This is in keeping with the consistent evidence on sex-differences in suicide rates, but as with suicide attempts in BD, the size of the difference is smaller than in general suicide samples (28), which show up to a four-fold difference, and is more in line with an approximate 2:1 ratio identified in a review of suicide in depression (26). Sex-based differences in methods of suicide have been reported in the broad literature, and may also be relevant to understanding sex-based differences in BD, but there was insufficient data to examine this possibility in detail.

A noteworthy finding is that a lifetime history of any substance use disorder was not associated with higher rates of suicide deaths in BD, however the OR of 1.20 (95% CI: 0.93–1.56) was in the direction of a positive correlation. Nonetheless, this contrasts with the elevated risk of suicide attempts in our analyses and the literature on higher rates of suicide deaths in general samples (90) as well as specific to depression (26) and schizophrenia (91). One possible explanation relates to sample characteristics, as the two most heavily weighted studies in our meta-analysis (Supplementary Fig. S4) were large population-based epidemiological samples that did not find a significant association, in contrast to the one pure clinical sample from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) that reported a strong association (OR = 8.05). This suggests the possible impact of Berkson’s bias (92), with a more severe sample of comorbid patients entering into a clinical protocol. This hypothesis, however, is speculative at best, and reinforces the importance of having more data on the specific connection between substance use and suicide deaths in BD, including mediating factors and greater details of the substance use in relation to phases of illness. Until these can be examined, the methodological limitations of our analysis and the divergence from the bulk of the broader literature on substance use and suicide suggest that our result must be interpreted with appropriate caution. It would also be important to further understand the association as it pertains to timing of substance use, as evidenced by recent data on self-poisoning deaths among people with BD which identified 41% of cases having alcohol in the system at the time of death (93).

Finally, first-degree family history of suicide was found to have the strongest association with suicide deaths in BD (OR = 2.91). This supports prior literature on the significance of family history of suicide on elevating suicide risk from general psychiatric samples (94–96), and reinforces the importance of integrating genetic, epigenetic, and social learning effects when building models of psychobiological contributors to suicidal behavior in BD (36, 97).

There are a number of important limitations that must be considered when interpreting these data. First, considerable heterogeneity exists in the available literature, but since the number of studies is not very large, we included all studies with either epidemiological or clinical samples. The largest studies included were usually prospective epidemiological samples, and the predominant concordance of results with smaller clinical samples should serve to strengthen the generalizability of our results. However it is possible that the magnitude or even presence of specific associations may be different within certain BD subpopulations. This degree of granularity could not be determined based on the available literature. Second, as noted earlier, the relationship in time between the variables of interest and the outcome of a suicide attempt or suicide death was not always known. For instance, higher lifetime rates of suicide attempts in subjects with a lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder does not provide information on whether these were contemporaneous and therefore cannot be used to determine the direction of the effect or other interactions. This was not the case with all variables, since a number are not time-based, but nonetheless the usual caution around association not equaling causation is relevant here. In a related limitation, we included studies with retrospective or prospective designs; therefore it is important to consider the significant findings as being evidence of correlation rather than for any attempt to assign levels of risk of suicide attempts or suicide for a particular patient. Retrospective studies also carry the limitation of recall bias, therefore while the reported data can serve to inform future studies aimed at determining this type of risk, prospective stratified designs are required. In a similar vein, the findings do not address causation, and the heterogeneity of data sources should limit the direct clinical ranking of correlates. The results of one variable should therefore not be compared to another, since different studies were used in the analyses. An additional limitation is that data on correlates of suicide attempts should not be assumed to be relevant for understanding risk of suicide deaths, as evidenced by the well described gender paradox (98) also seen here, as well as the discordant results on substance use disorders. Finally, a number of putatively important variables such as past suicide attempts, hopelessness, recent hospitalization, childhood abuse and smoking could not be meta-analyzed due to lack of sufficient number of studies with the required data reporting. This precludes considering the correlates reported in this paper as an exhaustive list of variables associated with suicide attempts or suicide in BD, and reinforces the importance of including all potential variables of interest in future studies of suicidal behavior in BD.

The principal objective of this report was to identify correlates of suicide attempts and suicide deaths in studies specific to BD. The meta-analytic results identified ten significant correlates of suicide attempts and two significant correlates of suicide deaths, some of which are only relevant to BD, and others that have been studied more broadly. As has been discussed earlier, there are a few noteworthy differences between the results we obtained and the broader literature on suicidal behavior and deaths among general samples (28), or even those focused on unipolar depressive disorder (26) or schizophrenia (91). While appropriate caution is required when interpreting the findings, our results support the importance of incorporating diagnosis-specific data on clinical variables relevant to BD, as well on the diagnosis-specific results from a broader set of correlates into the development of models for understanding suicide risk in BD (29, 36, 99). This conclusion has implications for future work on developing specific preventative programs and therapeutic interventions for people with BD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the International Society for Bipolar Disorders executive and staff who assisted with the organization of the task force, and the students who assisted with the literature review and provided statistical work (Jessika Lenchyshyn, BSc, Randy Rovinski, MSc).

Partial support for this project was provided by the Brenda Smith Bipolar Disorder Research Fund, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

Footnotes

Disclosures

AS has received research grants, speakers bureau honoraria, and/or advisory panel funding from Eli Lilly Canada, AstraZeneca Canada, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer Canada, Lundbeck Canada, and Sunovion. ETI has received honoraria from Servier for lecturing in educational meetings. LT has received funding from private donors at Aretæus Association and at McLean Hospital. DM has received grant support or served as a speaker for Abbott, Aché, Lundbeck, EMS, and Eurofarma. MS has received grant support from the Physicians’ Services Incorporated (PSI) Foundation and the Brenda Smith Bipolar Disorder Research Fund. J-MA has received research support and has acted as consultant and/or served on a speakers bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Eli Lilly & Co., Lundbeck, Roche, and Sanofi-Aventis. LVK has, within the preceding three years, been a consultant for Lundbeck and AstraZeneca. TG has received research support from NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, and The Pittsburgh Foundation; and Royalties from Guilford Press. AJL has received research grants from Janssen Ortho, AstraZeneca, Great West Life Insurance, and Eli Lilly Canada; and has acted as a consultant for Janssen Ortho. CAZ is listed as a co-inventor on a patent application for the use of ketamine and its metabolites in major depression, and has assigned his rights in the patent to the US government but will share a percentage of any royalties that may be received by the government. LNY has received research grants and/or been a member of advisory boards and a speaker for AstraZeneca, Dainippon Sumammito, Janssen, Eli Lilly & Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Lundbeck, Novartis, Servier, Sunovion, and Pfizer. GT, CR, FC, KH, AW, AB, Y-HC, ND, and ZR do not have any conflicts of interest to report.

Partial findings were presented during the symposia at the 16th Annual Conference of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Seoul, South Korea, March 18-21, 2014.

References

- 1.Roy A Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39: 1089–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tondo L, Lepri B, Baldessarini RJ. Suicidal risks among 2826 Sardinian major affective disorder patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007; 116: 419–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown GK, Beck AT, Steer RA, Grisham JR. Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000; 68: 371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sani G, Tondo L, Koukopoulos A et al. Suicide in a large population of former psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011; 65: 286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborn D, Levy G, Nazareth I, King M. Suicide and severe mental illnesses. Cohort study within the UK general practice research database. Schizophr Res 2008; 99: 134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barner-Rasmussen P Suicide in psychiatric patients in Denmark, 1971–1981. II. Hospital utilization and risk groups. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986; 73: 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyer EH, Mortensen PB, Olesen AV. Mortality and causes of death in a total national sample of patients with affective disorders admitted for the first time between 1973 and 1993. Br J Psychiatry 2000; 176: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osby U, Brandt L, Correia N, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001; 58: 844–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karch DL, Barker L, Strine TW. Race/ethnicity, substance abuse, and mental illness among suicide victims in 13 US states: 2004 data from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev 2006; 12 (Suppl. 2): ii22–ii27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baillargeon J, Penn JV, Thomas CR, Temple JR, Baillargeon G, Murray OJ. Psychiatric disorders and suicide in the nation’s largest state prison system. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2009; 37: 188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YY, Lee MB, Chang CM, Liao SC. Methods of suicide in different psychiatric diagnostic groups. J Affect Disord 2009; 118: 196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Absolute risk of suicide after first hospital contact in mental disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68: 1058–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takizawa T [Suicide due to mental diseases based on the Vital Statistics Survey Death Form]. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2012; 59: 399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS, Ignacio RV et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and risk of suicide in veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67: 1152–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon GE, Hunkeler E, Fireman B, Lee JY, Savarino J. Risk of suicide attempt and suicide death in patients treated for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2007; 9: 526–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tondo L, Isacsson G, Baldessarini R. Suicidal behaviour in bipolar disorder: risk and prevention. CNS Drugs 2003; 17: 491–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Søndergård L, Lopez AG, Andersen PK, Kessing LV. Mood-stabilizing pharmacological treatment in bipolar disorders and risk of suicide. Bipolar Disord 2008; 10: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pompili M, Gonda X, Serafini G et al. Epidemiology of suicide in bipolar disorders: a systematic review of the literature. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 457–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: a Swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70: 931–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170: 205–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessing LV, Sondergard L, Kvist K, Andersen PK. Suicide risk in patients treated with lithium. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 860–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonda X, Pompili M, Serafini G et al. Suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder: epidemiology, characteristics and major risk factors. J Affect Disord 2012; 143: 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other Axis I disorders. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 39: 896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon NM, Zalta AK, Otto MW et al. The association of comorbid anxiety disorders with suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in outpatients with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2007; 41: 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaffer A, Cairney J, Veldhuizen S, Kurdyak P, Cheung A, Levitt A. A population-based analysis of distinguishers of bipolar disorder from major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2010; 125: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawton K, Casanas ICC, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2013; 147: 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Psychiatric Association; Practice Guidelines for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Compendium 2006. Arlington, 2006: 1315–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mann JJ. A current perspective of suicide and attempted suicide. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136: 302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunders KE, Hawton K. Clinical assessment and crisis intervention for the suicidal bipolar disorder patient. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chesin M, Stanley B. Risk assessment and psychosocial interventions for suicidal patients. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 584–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005; 294: 2064–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz-Lifshitz M, Zalsman G, Giner L, Oquendo MA. Can we really prevent suicide? Curr Psychiatry Rep 2012; 14: 624–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitman A, Caine E. The role of the high-risk approach in suicide prevention. Br J Psychiatry 2012; 201: 175–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baethge C, Cassidy F. Fighting on the side of life: a special issue on suicide in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hauser M, Galling B, Correll CU. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence rates, correlates, and targeted interventions. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 507–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malhi GS, Bargh DM, Kuiper S, Coulston CM, Das P. Modeling bipolar disorder suicidality. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 559–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yerevanian BI, Choi YM. Impact of psychotropic drugs on suicide and suicidal behaviors. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 594–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Harriss L. Suicide and attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Novick DM, Swartz HA, Frank E. Suicide attempts in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: a review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Bipolar Disord 2010; 12: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dennehy EB, Marangell LB, Allen MH, Chessick C, Wisniewski SR, Thase ME. Suicide and suicide attempts in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). J Affect Disord 2011; 133: 423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: 1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romero S, Colom F, Iosif AM et al. Relevance of family history of suicide in the long-term outcome of bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68: 1517–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cassidy F Risk factors of attempted suicide in bipolar disorder. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2011; 41: 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sublette ME, Carballo JJ, Moreno C et al. Substance use disorders and suicide attempts in bipolar subtypes. J Psychiatr Res 2009; 43: 230–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potash JB, Kane HS, Chiu YF et al. Attempted suicide and alcoholism in bipolar disorder: clinical and familial relationships. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 2048–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oquendo MA, Currier D, Liu SM, Hasin DS, Grant BF, Blanco C. Increased risk for suicidal behavior in comorbid bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Clin Psychiatry 2010; 71: 902–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakagawa A, Grunebaum MF, Sullivan GM et al. Comorbid anxiety in bipolar disorder: does it have an independent effect on suicidality? Bipolar Disord 2008; 10: 530–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malloy-Diniz LF, Neves FS, Abrantes SS, Fuentes D, Correa H. Suicide behavior and neuropsychological assessment of type I bipolar patients. J Affect Disord 2009; 112: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valtonen HM, Suominen K, Mantere O, Leppamaki S, Arvilommi P, Isometsa E. Suicidal behaviour during different phases of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2007; 97: 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu CY, Bai YM, Yang YY, Lin CC, Sim CC, Lee CH. Suicide and parasuicide in psychiatric inpatients: ten years experience at a general hospital in Taiwan. Psychol Rep 1996; 79: 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neves FS, Malloy-Diniz LF, Correa H. Suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder: what is the influence of psychiatric comorbidities? J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70: 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaudhury SR, Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC et al. Does first episode polarity predict risk for suicide attempt in bipolar disorder? J Affect Disord 2007; 104: 245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J et al. Suicide attempts in major affective disorder patients with comorbid substance use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60 (Suppl. 2): 63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joyce PR, Light KJ, Rowe SL, Cloninger CR, Kennedy MA. Self-mutilation and suicide attempts: relationships to bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, temperament and character. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010; 44: 250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bega S, Schaffer A, Goldstein B, Levitt A. Differentiating between bipolar disorder types I and II: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). J Affect Disord 2012; 138: 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valtonen HM, Suominen K, Mantere O, Leppämäki S, Arvilommi P, Isometsä ET. Prospective study of risk factors for attempted suicide among patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8: 576–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swann AC, Dougherty DM, Pazzaglia PJ, Pham M, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG. Increased impulsivity associated with severity of suicide attempt history in patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 1680–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanchez-Gistau V, Colom F, Mane A, Romero S, Sugranyes G, Vieta E. Atypical depression is associated with suicide attempt in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009; 120: 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ryu V, Jon DI, Cho HS et al. Initial depressive episodes affect the risk of suicide attempts in Korean patients with bipolar disorder. Yonsei Med J 2010; 51: 641–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perroud N, Baud P, Preisig M et al. Social phobia is associated with suicide attempt history in bipolar inpatients. Bipolar Disord 2007; 9: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parmentier C, Etain B, Yon L et al. Clinical and dimensional characteristics of euthymic bipolar patients with or without suicidal behavior. Eur Psychiatry 2012; 27: 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moor S, Crowe M, Luty S, Carter J, Joyce PR. Effects of comorbidity and early age of onset in young people with bipolar disorder on self harming behaviour and suicide attempts. J Affect Disord 2012; 136: 1212–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grunebaum MF, Ramsay SR, Galfalvy HC et al. Correlates of suicide attempt history in bipolar disorder: a stress-diathesis perspective. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8: 551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Leon AC, Kocsis JH, Portera L. Association of recurrent suicidal ideation with nonremission from acute mixed mania. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1753–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gazalle FK, Hallal PC, Tramontina J et al. Polypharmacy and suicide attempts in bipolar disorder. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2007; 29: 35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Galfalvy H, Oquendo MA, Carballo JJ et al. Clinical predictors of suicidal acts after major depression in bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8: 586–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Azorin JM, Kaladjian A, Adida M et al. Risk factors associated with lifetime suicide attempts in bipolar I patients: findings from a French National Cohort. Compr Psychiatry 2009; 50: 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bellivier F, Yon L, Luquiens A et al. Suicidal attempts in bipolar disorder: results from an observational study (EMBLEM). Bipolar Disord 2011; 13: 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dalton EJ, Cate-Carter TD, Mundo E, Parikh SV, Kennedy JL. Suicide risk in bipolar patients: the role of co-morbid substance use disorders. Bipolar Disord 2003; 5: 58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Engström C, Brändström S, Sigvardsson S, Cloninger CR, Nylander PO. Bipolar disorder. III: Harm avoidance a risk factor for suicide attempts. Bipolar Disord 2004; 6: 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Finseth PI, Morken G, Andreassen OA, Malt UF, Vaaler AE. Risk factors related to lifetime suicide attempts in acutely admitted bipolar disorder inpatients. Bipolar Disord 2012; 14: 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, Frye MA et al. Factors associated with suicide attempts in 648 patients with bipolar disorder in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64: 506–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsai SY, Kuo CJ, Chen CC, Lee HC. Risk factors for completed suicide in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weeke A, Vaeth M. Excess mortality of bipolar and unipolar manic-depressive patients. J Affect Disord 1986; 11: 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sharma R, Markar HR. Mortality in affective disorder. J Affect Disord 1994; 31: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Black DW, Winokur G, Nasrallah A. Effect of psychosis on suicide risk in 1,593 patients with unipolar and bipolar affective disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1988; 145: 849–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dutta R, Boydell J, Kennedy N, VANO J, Fearon P, Murray RM. Suicide and other causes of mortality in bipolar disorder: a longitudinal study. Psychol Med 2007; 37: 839–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Holma KM, Haukka J, Suominen K et al. Differences in incidence of suicide attempts between bipolar I and II disorders and major depressive disorder. Bipolar Disord 2014; 16: 652–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rosenbluth M, Macqueen G, McIntyre RS, Beaulieu S, Schaffer A. The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid personality disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2012; 24: 56–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schaffer A, McIntosh D, Goldstein BI et al. The CANMAT task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid anxiety disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2012; 24: 6–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Watkins HB, Meyer TD. Is there an empirical link between impulsivity and suicidality in bipolar disorders? A review of the current literature and the potential psychological implications of the relationship. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 542–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuo WH, Gallo JJ, Tien AY. Incidence of suicide ideation and attempts in adults: the 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychol Med 2001; 31: 1181–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, DeLeo D et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989–1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996; 93: 327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nivoli AM, Pacchiarotti I, Rosa AR et al. Gender differences in a cohort study of 604 bipolar patients: the role of predominant polarity. J Affect Disord 2011; 133: 443–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baldessarini RJ, Undurraga J, Vazquez GH et al. Predominant recurrence polarity among 928 adult international bipolar I disorder patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2012; 125: 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Azorin JM, Bellivier F, Kaladjian A et al. Characteristics and profiles of bipolar I patients according to age-at-onset: findings from an admixture analysis. J Affect Disord 2013; 150: 993–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Coryell W, Fiedorowicz J, Leon AC, Endicott J, Keller MB. Age of onset and the prospectively observed course of illness in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2013; 146: 34–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64: 543–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leadholm AK, Rothschild AJ, Nielsen J, Bech P, Ostergaard SD. Risk factors for suicide among 34,671 patients with psychotic and non-psychotic severe depression. J Affect Disord 2014: 156: 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Murphy GE, Wetzel RD. The lifetime risk of suicide in alcoholism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990; 47: 383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gomez-Duran EL, Martin-Fumado C, Hurtado-Ruiz G. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of suicide in patients with schizophrenia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2012; 40: 333–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Westreich D Berkson’s bias, selection bias, and missing data. Epidemiology 2012; 23: 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schaffer A, Sinyor M, Reis C, Goldstein BI, Levitt AJ. Suicide in bipolar disorder: characteristics and subgroups. Bipolar Disord 2014; doi: 10.1111/bdi.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Large M, Smith G, Sharma S, Nielssen O, Singh SP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical factors associated with the suicide of psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011; 124: 18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ernst C, Mechawar N, Turecki G. Suicide neurobiology. Prog Neurobiol 2009; 89: 315–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J. Genetics of suicide: an overview. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2004; 12: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Manchia M, Hajek T, O’Donovan C et al. Genetic risk of suicidal behavior in bipolar spectrum disorder: analysis of 737 pedigrees. Bipolar Disord 2013; 15: 496–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schrijvers DL, Bollen J, Sabbe BG. The gender paradox in suicidal behavior and its impact on the suicidal process. J Affect Disord 2012; 138: 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sublette ME, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. Rational approaches to the neurobiologic study of youth at risk for bipolar disorder and suicide. Bipolar Disord 2006; 8: 526–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Suominen K, Mantere O, Valtonen H et al. Gender differences in bipolar disorder type I and II. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009; 120: 464–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.