Abstract

Poor body image is common among individuals seeking bariatric surgery and is associated with adverse psychosocial sequelae. Following massive weight loss secondary to bariatric surgery, many individuals experience excess skin and associated concerns, leading to subsequent body contouring procedures. Little is known, however, about body image changes and associated features from pre-to post-bariatric surgery and subsequent body contouring. The objective of the present study was to conduct a comprehensive literature review of body image following bariatric surgery to help inform future clinical research and care. The articles for the current review were identified by searching PubMed and SCOPUS and references from relevant articles. A total of 60 articles examining body image post-bariatric surgery were identified and 45 did not include body contouring surgery. Overall, there was great variation in standards of reporting sample characteristics and body image terms. When examining broad levels of body image dissatisfaction, the literature suggests general improvements in certain aspects of body image following bariatric surgery; however, few studies have systematically examined various body image domains from pre-to post-bariatric surgery and subsequent body contouring surgery. In conclusion, there is a paucity of research that examines the multidimensional elements of body image following bariatric surgery.

Keywords: Obesity, Bariatric Surgery, Body Image, Body Dissatisfaction, Body Contouring Surgery

Introduction

“My abdomen was like a part that didn’t belong to me and now it’s all part of me again.” (bariatric surgery patient who subsequently underwent body contouring surgery 1, p.548)

Bariatric surgery is the most effective available treatment for severe obesity producing substantial weight losses that are reasonably sustained over time along with significant improvements in obesity-related medical comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension) and mortality rates 2. Research has also found that bariatric surgery is associated with broad improvements in psychosocial functioning over time although there appears to be considerable heterogeneity in the benefits over time across different domains 3, 4.

The present review focuses on the effects of bariatric surgery on body image. Body image is a multidimensional construct 5 consisting of cognitive, affective, behavioral, and perceptual aspects 6. Various forms of body image dissatisfaction are linked to a host of diverse psychosocial sequelae and areas of impaired functioning including, for example, binge eating, depression, social anxiety, and poorer physical health-related quality of life 7, 8. Among individuals seeking bariatric surgery, aspects of body image dissatisfaction are associated with binge eating, depression, and lower self-esteem 9. Thus, it is not surprising that approximately 1 in 5 bariatric surgery patients have identified appearance concerns as the primary motivator for surgery 10. While the weight loss and metabolic outcomes of various bariatric surgeries have been well-documented, the complexities of body image post-operatively remain poorly understood.

Another related aspect of body image that requires careful review among bariatric surgery patients involves the issue of excess skin following massive weight loss, which appears to be both very common 11–13 and quite troublesome 14. Excess skin has been linked to dermatitis and itching, 12, difficulty exercising 12, irritation in skin folds 14, difficulty finding or fitting in clothes 15, 16, intimate relationship distress 15, and high levels of daily impairment 14. Accordingly, some bariatric patients have elected to undergo body-contouring surgery (BCS) following bariatric surgery. As many as 84.5% of bariatric surgery patients desire subsequent BCS, with greater percentages for women than men, 75% compared to 68%, respectively 12. Despite the desire for BCS, the percentage of bariatric patients who actually undergo subsequent BCS is much lower, ranging from 21% 11 to 47% 13, which may be due, in part, to financial barriers and lack of insurance coverage 13. Little is known about the trajectory of body image concerns from pre- to post-bariatric surgery and with respect to BCS.

The aim of the present study was to conduct a comprehensive literature review of body image following bariatric surgery and subsequent BCS to help elucidate the findings from the current literature and to provide recommendations for future research in this area.

Method

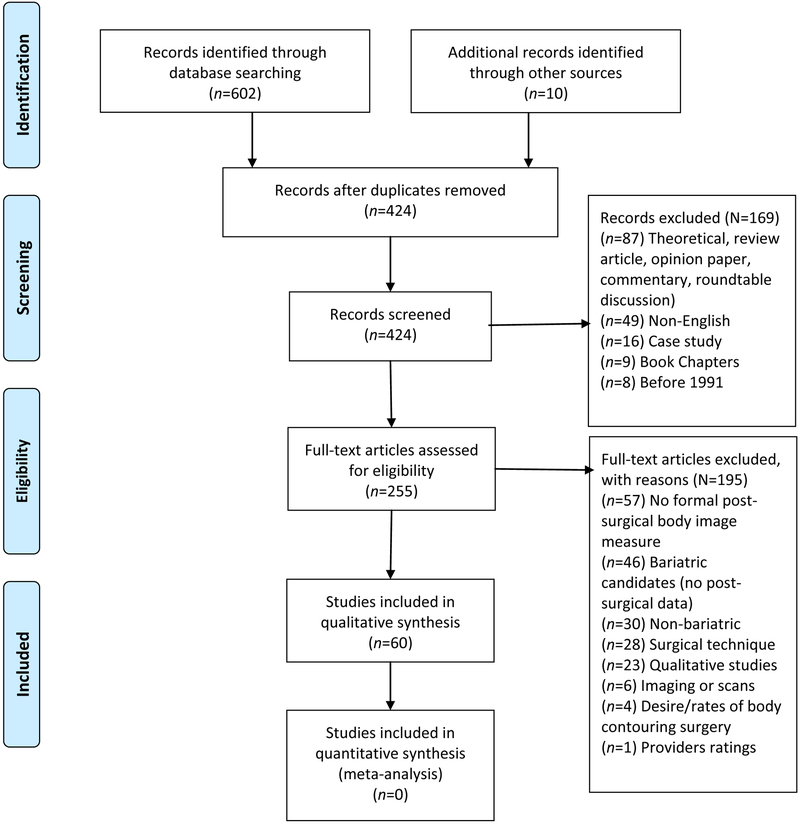

The articles for the current review were identified by searching PubMed and SCOPUS and by searching references from relevant articles. Search terms included “bariatric surgery,” “gastric bypass,” “lap-band,” “Roux-en-Y,” and “sleeve gastrectomy,” coupled with body image terms such as “body image” and “body dissatisfaction.” PubMed and SCOPUS generated 321 and 281 articles, respectively. Studies were included if a body image measure was utilized in a post-bariatric surgery group. Both retrospective and prospective designs were included. Exclusion criteria included studies prior to 1991 (the National Institutes of Health distributed guidelines on the surgical management of obesity in 1991), non-English articles, case reports, qualitative studies (see Coulman et al.17), and articles focusing on only bariatric candidates without follow-up post-operative data. Additionally, studies focusing on generic level of satisfaction without a specific body image measure were excluded. Author 1 searched and screened articles. Both authors 1 and 2 reviewed all relevant articles and met to discuss articles. When an aspect of a study was unclear (i.e., sample characteristics or body image measure), a collaborative decision was made by both authors 18, 19. Refer to the PRISMA Flow Diagram 20 (Figure 1) for a visual depiction of the inclusion/exclusion process. The original search ended on April 13, 2017.

Prisma 2009 Flow Diagram

Results

A total of 60 articles examining body image post-bariatric surgery were identified. Of these, 18 (30.0%) were cross-sectional, 38 (63.3%) were observational longitudinal, two (3.3%) were scale development 21, 22, and one study was a treatment outcome study (published as two articles; one with pre- to post-data 23 and one with follow-up data through six months post-treatment 24). All but two studies 25, 26 examined adults, the majority of which included female participants. Overall, there was great variation in standards of reporting sample characteristics. A total of 22 (36.7%) studies had a sample size of at least 100 participants, while 27 (45.0%) had a sample size of less than 50 participants. According to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, the quality of the level of evidence was low, with a modal score of 4 (an average rating of 3.8) on a scale from 1 (highest quality) to 5 (lowest quality).

The remainder of this section will first summarize the results of studies examining body image after bariatric surgery without BCS, followed by a summary of studies examining body image among individuals who had bariatric surgery and sought or underwent subsequent BCS.

Studies examining body image following bariatric surgery (without BCS)

A total of 45 articles were classified as examining body image post-bariatric surgery without BCS. Table 1 lists the study, study design and timeframe, sample characteristics, bariatric surgery type, body image measures, and summary of the relevant body image findings for these studies. Of these 45 articles, 12 were cross-sectional and 33 were longitudinal designs; only two 23, 24 of which reported findings from a pilot randomized clinical trial. Among the 12 cross-sectional studies, time since surgery ranged from 1–3 weeks 27 to 10 years post-surgery 28. Of the 31 observational longitudinal studies, follow-up periods ranged from 5 months to “48 or more” months post-bariatric surgery; however, 41.9% (n=13) 25, 29–40 and 45.2% (n=14) 3, 26, 41–52 of these studies included follow-up assessments through 12 and 24 months post-bariatric surgery, respectively. One study was a small treatment outcome study (n=39 randomized patients) comparing acceptance and behavioral therapy to treatment-as-usual after six weeks of treatment 23 and after a six-month follow-up period 24.

Table 1.

Summary of articles reporting body image results following bariatric surgery

| Study (ref) by Design and Year |

Study Design Timeframe |

Sample Characteristics Gender: n or % Race: n or % Age: Mean±SD years Post-WLS BMI: Mean±SD kg/m2 |

WLS Typea

· n included if > 1 WLS |

Body Image Measures ·Subscales |

Summary of Relevant Body Image Findings Response Rate (cross-sectional design) or Retention Rate (longitudinal design) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adami (1998) | Cross-sectional 3 groups 1. Obesity without WLS 2. Post-WLS · 24-158 months (M:35 months) 3. University healthy without obesity (control) |

N=47-131 Obesity without WLS n=110 Post-WLS n=131 Without Obesity n=47 Gender: Overall NI Race: NI Age range: 17-63 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI BMI by post-WLS groups ranged from 27.9-28.2 |

Biliopancreatic diversion | BAQ BSQ EDI: · BD |

Body image findings presented by groups: · Adult-onset obesity vs. early-onset obesity vs. control Post-WLS group had similar BAQ attractiveness scores as control without obesity and lower BAQ disparagement scores than non-WLS obesity group. Post-WLS patients with adult-onset obesity reported similar BAQ, BSQ, and BD scores as control group. Post-WLS patients with early-onset obesity reported lower BSQ scores than non-WLS obesity group and higher BSQ scores than control group without obesity. Response rate: NI |

| Guisado (2002) | Cross-sectional · 18 months post-WLS |

N=100 Gender: Female=85 Male=15 Race: NI Age: 40.50±11.15 Post-WLS BMI: 33.49±6.31 |

Vertical banded gastroplasty | EDI | Body image findings presented by weight loss groups: · Weight loss >30% (n=56) vs. Weight loss <30% (n=44) Weight loss >30% had lower body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, and global EDI scores than weight loss <30%. Response rate: NI |

| Neven (2002) | Cross-sectional 4 groups 1. Pre-WLS Post-WLS: 2. 1-3 weeks 3. 6 months 4. 12 months |

N=14-24 Pre-WLS n=20 1-3 weeks post n=14 6 month post n=24 12 month post n=20 Gender: NI Race: NI Age: Total age NI; Age by group ranged from 37.9±8.5 to 41.2±8.9 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI BMI by group ranged from 53.8±10.9 to 58.6±13.2 |

Bypass | MBSRQ: · AE FRS |

MBSRQ AE: Significant improvement in perceptions of body image post-surgery, particularly between pre-WLS and 6 months post-WLS. There was also a significant change in body image between 6 and 12 months post-WLS. FRS: The ideal silhouette figure did not change; however, the differences between the current and ideal image was smaller at 6 and 12 months post-WLS. Response rate: NI |

| Hotter (2003) | Cross-sectional · 12.5±4.6 months post-WLS |

N=77 Gender: Female=65 Male=12 Race: NI Age: 40.1±9.9 Post-WLS BMI: 30.8±6.1 |

Band | BIQ-20: German version FBeK: German version |

Body image findings presented by groups: · 'Good outcome group' vs. 'Poor outcome group' 'Good outcome group' had improvements on BIQ-20 and FBeK subscales. 'Poor outcome group' had poorer body image on various aspects of body image including body disparagement, low levels of self-efficacy, and bodily control. Response rate: 67% |

| Madan (2008) | Cross-sectional 2 groups 1. Pre-WLS 2. Post-WLS · Time since surgery: NI |

N=27 Pre-WLS n=8 Post WLS n=19 Gender: NI Race: NI Age: NI Post-WLS BMI: 33±10 |

Bypass: · n=15 Band: · n=12 |

BESAA | Post-WLS group reported better body image than pre-WLS group. Response rate: NI |

| Buser (2009) | Cross-sectional · 6-18 or 19-40 months post-WLS |

N=106 Gender: Female=106 Male=0 Race: NI Age: NI Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI BMI by groups ranged from 27.01±4.29 to 34.54±8.16 |

Bypass | BISS | Body image findings presented by groups: · History of sexual abuse versus no history sexual abuse No significant differences in body dissatisfaction between the two groups at 6-18 months or 19-40 months post-WLS. Response rate: Overall, NI. Of the N=136 who agreed to participate, 112/136 (82.4%) provided usable data. |

| Larsen (2009) | Cross-sectional · 42.6-46.0 months post-WLS |

N=34 BED n=16 Non-BED n=18 Gender: Female=34 Male=0 Race: NI Age: Overall age NI. Age by groups ranged from 38.4±7.6 to 42.7±6.5 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI. BMI ranged from 35.8±6.0 to 40.1±8.2. Matched on demographic variables |

Band | EDE: · WC · SC |

Body image findings presented by groups: · BED versus non-BED groups post-WLS BED group had higher shape concern, eating concern, and restraint compared to non-BED following bariatric surgery, signifying large effect sizes. The two groups did not differ on weight concerns. Response rate: 68% |

| Kinzl (2011) | Cross-sectional · 10 years post-WLS |

N=112 Gender: Female=92 Male=20 Race: NI Age: 49 Post-WLS BMI: 31.1 |

Band | BIQ: German version is FKB-20 | Those satisfied with weight loss reported statistically significantly less rejection of their body and greater vital body dynamics. Greater excess weight loss was negatively correlated with rejecting body assessment and positively correlated with greater vital body dynamics. Response rate: 62.2% |

| Conceicao (2014) | Cross-sectional 3 groups: 1. Pre-WLS Post-WLS 2. Within 24 Months · 11.4±4.0 months post-WLS 3. >24 Months · 55.8±34.4 months post-WLS |

N=339 Pre-WLS group: n=176 Post-WLS groups: · Within 24 months: n=110 · >24 months: n=53 Gender: Female: Overall NI. 88.1%−89.0% by groups Race: NI Age: Overall age NI. Age by groups ranged from 41.7±10.8 to 43.5±10.9 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI. BMI ranged from 30.0±4.6 to 37.6±6.1. |

Band: · n=95 Sleeve gastrectomy: · n=12 Bypass: · n=61 |

BSQ: Portuguese version | Body image findings presented by groups: · Loss-of-control eating versus not Loss-of-control eating group reported significantly greater BSQ scores at pre-WLS and the >24 months post-WLS phases than did the group without loss-of-control eating. Response rate: Pre-WLS=65%, Post-WLS: 90% |

| Mirijello (2015) | Cross-sectional · 2-218 months post-WLS (M:44 months) |

N=46 1. Pre-WLS group: n=20 2. Post-WLS group: n=26 3. Control group: n=50 Gender (Surgical): Females=32 Males=14 Race: NI Age: 42.5±10.9 Post-WLS BMI: 34.6±6.9 Control group matched on gender, age, residence, employment, and socio-economic status |

Biliopancreatic diversion | BSQ | Pre-WLS group had greater distress about body shape than post-WLS group. BSQ scores were significantly correlated with BMI and weight. There was an inverse correlation between change in BMI and BSQ. Response rate: 76.7% |

| Ramalho (2015) | Cross-sectional · 19.0±10 months post-WLS |

N=61 Gender: Females=61 Male=0 Race: NI Age: 41.3±8.7 Post-WLS BMI: 30.45±5.35 |

Bypass: · n=42 Band: · n=17 Sleeve gastrectomy: · n=2 |

BSQ Excessive skin impairment survey | Greater concerns with BSQ weight and shape was associated with greater impairment due to excessive skin. Concerns with body image negatively correlated with all sexual functioning domains, except pain during intercourse, and with greater depressive symptoms. Women with sexual dysfunction reported greater concerns with BSQ weight and shape. Excessive skin impairment was not correlated with %TWL Response rate: 54.5% |

| Ivezaj (2017) | Cross-sectional · 6 months post-WLS |

N=71 Gender: Females=60 Males=11 Race: White=39 Black=22 Hispanic=9 Other=1 Age: 47.3±10.1 Post-WLS BMI: 37.9±8.2 |

Sleeve gastrectomy | EDE-BSV: · WC · SC |

Body image findings presented by groups: · Bariatric-BED (Bar-BED) vs not Bar-BED Bar-BED group had significantly greater EDE weight and shape concerns than the non-Bar-BED group. Lifetime history of BED was associated with greater EDE weight and shape concerns than no lifetime BED history. Response rate: NI (treatment-seeking RCT) |

| Adami (1999) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 36 months |

N=30 Gender: Females=21 Males=9 Race: NI Age: 36.8 Post-WLS BMI: 30.6±0.7 Control group: n=30 Control group matched on gender and age Control BMI: 23.4±0.4 |

Biliopancreatic diversion | BAQ BSQ EDI: · BD |

EDI BD and BAQ’s feeling fat, attractiveness, and body fatness scores were similar to controls without obesity 36 months post-WLS. Significant reductions in BSQ scores post-WLS, but higher than control group without obesity. Significant reductions in BAQ’s disparagement and salience of shape post-WLS, but higher than control group without obesity. No change in BAQ strength and fitness post-WLS; these scores were similar to the control group. Retention: NI |

| Dixon (2002) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months · 24 months · 36 months · 48 or more |

N=322 N=122 completed paired preoperative and 12 month post-operative surveys. Gender: Female=274 Men=48 Race: NI Age: 41±10 Post-WLS BMI: 32.9±6-35.1±6 |

Band | MBSRQ: · AE · AO |

Mean MBSRQ AO scores did not differ post-WLS. No significant correlation between 12 month AO and BMI. Significant improvements in MBSRQ AE, but AE scores did not reach community norms. Improvements in MBSRQ AE was associated with greater improvement in mental measures of quality of life, lower BDI scores, and greater percent excess weight loss. Women, younger age, and lower BMI predicted the greatest discrepancy between MBSRQ AO and AE scores. Retention: 12 months: 64.9%, 24 months: 46.0%, 36 months: 24.8%, 48 months or more: 19.3% |

| Dixon (2003) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=487 N=262 paired pre- and 1-year post-WLS Gender: Female=85% Male=15% Age: 41.2±9.7 Post-WLS BMI: 44.1±7.4 |

Band | MBSRQ: · AE · AO |

Decreases in BDI were correlated with AE improvements. MBSRQ AO scores were higher for women than men. Women with severe obesity had significantly greater MBSRQ discrepancy (AO–AE) than men. Most women < 35 years old with a MBSRQ AE score <1.6 (mean) had a Beck Depression Inventory score of 23 or greater, signifying major depressive symptoms. Retention: NI |

| Grilo (2006) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=137 Gender: Female=122 Male=15 Race: White=97 African American=23 Hispanic American=15 Other=2 Age: 42.3±10.2 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI. BMI by groups ranged from 32.51±5.04 to 33.77±6.03 |

Bypass | BSQ EDE-Q: · WC · SC |

Body image improvements observed from pre- to post-WLS. Body image findings presented by groups: · History of sexual abuse vs other maltreatment vs none Other maltreatment group had higher baseline BSQ and EDE-Q weight concern scores. Post-WLS, the three groups did not differ significantly on measures of body image. Retention: NI |

| Hrabosky (2006) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months · 12 months |

N=109 Gender: Female=97 Male=12 Race: White=73 Black=20 Hispanic=15 Asian=1 Age: 42.5±10.4 Post-WLS BMI: 33.04±5.61 |

Bypass | BSQ EDE-Q: · WC · SC |

Significant improvements observed in BSQ and EDE-Q subscales from pre- to 6 months post-WLS; EDE-Q weight concerns continued to improve at 12 months post-WLS. None of the three body image scales significantly predicted changes in BMI at 6 or 12 months post-WLS. Most reached body image norms 6 months post-WLS. At least 81% at 6 and 85% at 12 months reported clinically significant reductions in body dissatisfaction and concerns. Retention: NI |

| Masheb (2006) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months |

N=145 Gender: Female=129 Males=16 Race: White=98 African American=25 Hispanic American=19 Age: 42.1±10.3 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass | BSQ EDE-Q: · Over-valuation |

Improvements were observed in overvaluation and body image dissatisfaction post-WLS. Body image dissatisfaction and overvaluation were significantly correlated at both assessments. Body image dissatisfaction was related to changes in self-esteem and negative affect and overvaluation was related to changes in self-esteem. Change in overvaluation was not related to change in BMI. Retention: NI |

| White (2006) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=139 Gender: Female=124 Male=15 Race: White=98 African American: 23 Hispanic American: 16 Other: 2 Age: 42.4±10.2 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI. BMI by groups ranged from 32.9±5.7 to 33.9±5.3 |

Bypass | BSQ EDE-Q: · WC · SC |

Improved body image scores were observed post-WLS. Body image findings presented by pre-WLS groups: · Regular binge-eating episodes versus no binge episodes The regular binge-eating group reported statistically greater post-WLS EDE-Q SC scores than the no binge-eating group. Retention: NI |

| De Panfilis (2007) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=35 Gender: Female=31 Males=4 Age: 41.2±8.3 years Post-WLS BMI: 37.8±5.5 |

Band | BUT | Overconcern with physical appearance, body image-related avoidance behaviors, rituals involving checking physical appearance, and body image dissatisfaction significantly decreased post-WLS. Weight phobia, feelings of detachment or estrangement from one’s body, and uneasiness towards single body parts or functions did not change post-WLS. Less body image impairment was related to post-WLS reductions in binge-eating behaviors, after controlling for weight loss. Body image dissatisfaction was not related to weight loss. Retention: NI |

| Leombruni (2007) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months |

N=38 Gender: Female=32 Male=6 Race: NI Age: 39.80±9.92 Post-WLS BMI: 32.98±5.29 |

Vertical banded gastroplasty | BSQ EDI-2 |

Significantly lower BSQ and EDI-2 scores post-WLS. Greater EDI-2 body dissatisfaction was associated with greater weight loss. Retention: 73.1% |

| Colles (2008) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=129 Gender: Females=103 Males=26 Race: NI Age: 45.2±11.5 Post-WLS BMI: 35.0±6.0 |

Band | MBSRQ: · AD · AE · AO |

MBSRQ AD and AE improved significantly. Body image findings presented by groups: · Post-WLS Uncontrolled eating vs not Uncontrolled eating group reported lower MBSRQ AO and AE scores than the group without uncontrolled eating. Higher MBSRQ AD predicted poorer percent weight loss. Retention: 65.9%; Paired data |

| Morrow (2008) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 2 months · 5 months |

N=24 Gender: Female=22 Male=2 Race: NI Age: 18-52 Post-WLS BMI: 33.8±3.5 |

Bypass | FRS modified |

Body image discrepancy ratings decreased significantly from baseline to 2 months and 5 months post-WLS. Body image distortion ratings increased significantly. Body image findings presented by groups: · Post-WLS Night Eating versus No Night Eating Trend for increases in body image distortion for the Night Eating group compared to the group without night eating. Retention: 33.3% |

| van Hout (2008) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months · 12 months · 24 months |

N=104 Gender: Female=91 Male=13 Race: NI Age: 38.4±8.3 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Vertical banded gastroplasty | BAT | Significant decreases in BAT scores between pre-WLS and 6, 12, and 24 months post-WLS, but no significant changes between 6 and 12 months or 12 and 24 months. More positive body image related to lower BMI. Pre- and post-WLS body image did not reach norms. Retention: 79.4% |

| van Hout (2009) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 24 months |

N=112 Gender: Female=98 Male=14 Race: NI Age: 38.8±8.3 Post-WLS BMI: 31.9±5.9 |

Vertical banded gastroplasty | BAT EDE-II |

Post-WLS scores revealed improved body attitude. Scores were better than group of female weight watchers, but did not reach norms. Post N: 76.7% |

| Munoz (2010) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=57 Gender: Female: 82% Male: 18% Race: White: 68% African American: 21% Hispanic: 11% Age: 39±4.3 Post-WLS BMI: 37.4 |

Bypass | FRS | Post-WLS, there was a significant decrease in perceived and ideal body shape, and discrepancy between the two. Participants selected smaller ideal body shapes over time, resulting in nearly one full decrease in body size at 12 months post-WLS. Retention: NI |

| Sarwer (2010) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 5 months · 10 months · 21 months |

N=200 Gender: Female=164 Male=36 Race: White: 87% African American: 9% Age: 42.6±9.9 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass | BIQOLI BSQ |

Body image improvements were observed from pre-WLS to each post-WLS assessment. Body image changes was related to health quality of life. Greater weight loss was associated with significant improvements on BIQOLI, but not with changes in BSQ. Retention: 5 months: 99.0%, 10 months: 73.5%; 23 months: 56% |

| Thonney (2010) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: ·Baseline Post-WLS: ·12 months ·24 months |

N=43 Gender: Female=43 Male=0 Race: NI Age: 39.2±1.4 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass | EDE-II | Statistically significant improvements in body image observed 12 months post-WLS. Body dissatisfaction normalized 24 months post-WLS. Retention: NI |

| White (2010) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months · 12 months · 24 months |

N=361 Gender: Female=311 Male=50 Race: White=294, Black= 33, Hispanic-American=26, Other/Missing=8 Age: 43.7±10.0 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI |

Bypass | EDE-Q · WC · SC |

Improvements in EDE-Q WC and SC observed post-WLS. Body image findings presented by groups: · Loss-of-control eating vs no loss-of-control eating Loss-of-control eating group had greater EDE-Q WC and SC than those without loss-of-control eating post-WLS. Retention: 6 months: 86.1%, 12 months: 86.1%; 24 months: 47.4% |

| Zeller (2011) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 month · 12 month · 18 month · 24 month |

N=16 adolescents Gender: Female: 62.5% Male: 37.5% Race: White: 87.5% Age: 16.2±1.4 years Post-WLS BMI: 38.40±7.53 |

Bypass | IWQOL-K · Body esteem |

Clinically significant improvements from pre-WLS to 6 months post-WLS, and from 6 to 12 months post-WLS. Body image scores from 12 months onwards were not significantly different. Retention: 6 months: 87.5%, 12 months: 93.8%, 18 months: 93.8%; 24 months: 87.5% |

| Ortega (2012) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months · 12 months |

N=60 Gender: Female=46 Male=14 Race: NI Age: 44.05±10.86 Post-WLS BMI: 29.9±4.8 |

Bypass | BSQ Spanish version | Body improvements observed post-WLS. Greater post-WLS body image dissatisfaction was related to greater psychological discomfort 12 months post-WLS. Retention: NI |

| Ratcliff (2012) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months · 12 months |

N=16 adolescents Gender: Female: 69% Male: 31% Race: White: 75% Age: 16.3±1.2 years Post-WLS BMI: 41.11±9.62 |

Bypass | IWQOL-K · Body esteem Stunkard FRS: · Discrepancy |

Reduced body image discrepancy during first 12 months post-WLS, with the most reduction during first six months. No significant association between current body size estimation and attitudinal body image measures. Body image discrepancy was related to attitudinal body image dissatisfaction and weight-related quality of life. Percent excess weight loss was not related to body image discrepancy or IWQOL-K body esteem. Retention: 88% |

| Teufel (2012) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=51 Gender: Female=33 Male=18 Race: White=51 Age: 43.76±9.14 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Sleeve gastrectomy | BIQ-20: German version |

Improvements were observed in body image, self-evaluation of the body, and perceptions of body dynamics 12 months post-WLS, but did not reach norms. No sex differences in body image pre- or post-WLS. Body image was not related to weight or negative affect. Retention: 82.3% |

| Lanza (2013) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 36 months |

N=98 Gender: Female=98 Male=0 Race: NI Age: 38.5±9.0 Post-WLS BMI: 31.0±7.8 |

Bypass | EDI-2 | Body dissatisfaction improved three years post-WLS. Negative relationship between body dissatisfaction and excess weight loss. Retention: 59.2% |

| Gordon (2014) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months · 12 months · 24 months · Last clinical Observation (44.4±19.7 months) |

N=333 Gender: Female=282 Male=51 Age: 35.4±9.5 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass | BSQ: Brazilian version | Higher body image dissatisfaction positively correlated with weight loss at 24 months post-WLS. Lower BSQ scores were correlated with lower percent excess weight loss at 24 months and the last observation. On the last clinical observation after two years, body shape dissatisfaction remained an independent predictor of greater percent excess weight loss. Retention: 6 months: 85.9%, 12 months: 73%, 24 months: 45.3%, Last clinical observation: 67.9% |

| Matini (2014) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months |

N=67 Gender: Female=63 Male=4 Age: 36.8±8.5 BMI: 48.8±4.7 Post-WLS BMI: 35.7±3.9 |

Bypass | EDI-3 · Drive for thinness · Bulimia · BD |

Post-WLS, significant reductions in EDI drive for thinness, bulimia, and body dissatisfaction subscales were observed. No significant relationship between these subscales and weight loss six months post-WLS. Retention: NI |

| Melero (2014) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=46 Gender: Female=36 Male=10 Race: NI Age: 37 Post-WLS BMI: 29±3 |

Vertical laparoscopic gastrectomy | BSQ EDI-1 |

Post-WLS, significant improvements in BSQ body concerns and EDI-1 body dissatisfaction. Retention: NI |

| Neff (2014) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months |

N=217 Gender: Female=174 Male=43 Race: NI Age: Overall NI. Age by surgical type was 49±11 and 44±13 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass: · n=148 Band: · n=69 |

King’s Obesity Staging System BI | Body image improved after RYGB, but not band. Body image scores were not associated with change in BMI. When examining paired comparisons, body image did not differ by surgical procedure. Retention: NI |

| Sarwer (2014) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months · 24 months |

N=106 Gender: Female=106 Male=0 Race: White=102; Black=3 Other=1; Hispanic=1 Age: Median=41 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass: · n=85 Band: · n=21 |

BIQLI BSQ |

Women reported significant improvements in body image at 12 and 24 months post-WLS. Retention: 84.0% for both follow-ups |

| Sarwer (2015) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months · 24 months · 36 months · 48 months |

N=32 Gender: Female=0 Male=32 Race: White=32 Hispanic=1 Age: Median=48 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass | BIQLI BSQ |

Men reported significant improvements in body image for both measures at each post-WLS assessment compared to pre-WLS. Retention: 87.5% for all follow-ups |

| Devlin (2016) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 12 months · 24 months · 36 months |

N=183 Gender: Female=152 Male=31 Race: White=169; Black=12 Multi-race=1; Hispanic=8 Age: Median=46.0 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass: · n=111 Band · n=72 |

EDE-BSV · WC · SC |

EDE-BSV weight and shape concerns were significantly lower at 12 and 36 months post-WLS compared to pre-WLS. Retention: 12 months: 85%, 24 months: 78%; 36 months: 67% |

| Wimmelmann (2016) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Before diet-induced weight loss · Two months post diet Post-WLS: · 4 months · 18 months |

N=40 Gender: Female=28 Male=12 Age: 39.5±8.9 Post-WLS BMI: NI 14 had diabetes |

Bypass | Body Image Questionnaire | Weight-related body image scores improved significantly at 4 and 18 months post-WLS. Women had lower (worse) body image scores than men. Physical fitness did not make modest contributions to variations in weight-related body image. Body image findings presented by groups: · Diabetes versus no diabetes No significant main or interaction effects of diabetes for the weight-related body image subscale post-WLS. Retention: 4 months: 77.5%, 18 months: 57.5% |

| Nickel (2017) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 6 months · 24 months |

N=41 Gender: Female=17 Male=13 Race: NI Age: 42.9±12.4 Post-WLS BMI: 33.0±6.3 |

Bypass: · n=14 Sleeve gastrectomy: · n=16 |

BIQ · Body Image · Cosmetic · Self-confidence |

Body image improved significantly at 6 and 24 months. No difference in BIQ body image, cosmetic results, or self-confidence between 6 and 24 months post-WLS. Significant correlation between post-WLS body image and mental health functioning. No significant correlation between body image and BMI or percent excess weight loss. Retention: 73.2% |

| Weineland (2012a,b) | Treatment Outcome · 4-38 months Post-WLS M:15.46 months · Baseline: pre-treatment · 6-week treatment · 6-month follow-up assessment |

N=39 Gender: Female=35 Male=4 Race: NI Age: 43.08 Post-WLS BMI: 27.19 |

Sleeve gastrectomy: · n=25 Bypass: · n=14 |

BSQ: Short version EDE-Q: · WC · SC |

Significant effect between group and time at post-treatment for EDE-Q weight and shape concerns with medium effect for weight concerns and large effect for shape concerns at post-treatment. Significant interaction effect between time and treatment for BSQ with medium effect size at post- and 6 months. Treatment group had large and significant improvements in BSQ and EDE-Q WC and SC from pre- to post and follow-up assessment. Retention ACT: Post: 78.9%, Follow-up: 63.2% Retention TAU: Post: 94.7%, Follow-up: 85.0% |

Note.

'Bypass' includes papers describing gastric bypass and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; “Band” includes papers describing various forms of adjustable banding procedures; AD=Appearance Dissatisfaction; AE=Appearance Evaluation; AO=Appearance Orientation; BAQ=Body Attitude Questionnaire; BAT=Body Attitude Test; BD=Body Dissatisfaction; BESSA=Body-Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults; BIQ=Body Image Questionnaire; BIQOLI=Body Image Quality of Life Inventory; BISS=Body Image State Scale; BMI=Body Mass Index; BSQ=Body Shape Questionnaire; BUT=Body Uneasiness Test; EDE=Eating Disorders Examination; EDE-Q=Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire; EDI=Eating Disorder Inventory; FRS=Figure Rating Scale; IWQOL-K=Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Kids; MBSRQ=Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire; NI=Not Indicated; SC=Shape Concern; WC=Weight Concern; WLS=Weight Loss Surgery

A total of 18 different body image measures were identified throughout this literature and none were validated specifically among post-operative bariatric surgery patients. Overall, body image was examined with respect to pre- to post-operative changes and clinical correlates. Based on the current conceptualization and various measurements of body image post-bariatric surgery, general improvements in body image were typically observed among adults 3, 27, 29–32, 34–39, 42–48, 50–58 and adolescents 25, 26 after bariatric surgery; some studies, however, reported improvement in only some specific body image domains but not others 33, 41, 42, 58. For example, de Panfilis et al. 33 found that fear of being fat, feelings of detachment from one’s body, and uneasiness towards particular body parts did not improve post-surgery. Six studies 31, 37, 42–44, 46 which reported whether post-operative body image scores were comparable to “norms”, which varied by study (i.e., women with average BMI’s in the “normal” range or the “general population”), yielded mixed findings. Taken together, these results suggest that while certain body image improvements are observed post-surgery, these improvements may not necessarily reach norms.

In addition to examining changes in body image, 17 studies 28, 31, 33, 34, 37, 39, 42, 43, 45, 48, 49, 52, 53, 56, 57, 59, 60 examined the relationship between post-operative body image and weight. Nearly half of these 17 studies (41.2%) reported a relationship between greater weight loss and improvements in body image 28, 34, 43, 48, 53, 57, 59. In contrast, one study 49 found an association between greater post-operative body dissatisfaction and greater weight loss. Sarwer et al. 47 reported that greater weight loss was related to improvements in body image quality of life, but not general weight and shape concerns, while Dixon et al 42 found that appearance evaluation, but not appearance orientation was related to BMI. Seven studies 31, 33, 37, 39, 52, 56, 60 did not find an association between body image scores and BMI or weight changes following surgery. Taken together, the literature on post-operative body image changes and weight outcomes is mixed.

Eight studies 32–34, 47, 58, 61–63 examined body image in relation to eating behaviors post-bariatric surgery, including loss of control eating 47, 62 or “uncontrolled eating” 34, binge eating 33, 61, and night eating 58. Greater loss-of-control eating was associated with greater shape and weight concerns 47, 63, higher body shape scores pre- and post-operatively, and lower appearance orientation and appearance evaluation scores 34. De Panfilis et al. 33 reported a relationship between decreased binge eating and body image improvements. Similarly, two studies found that individuals with post-operative binge eating 32 or binge eating disorder 61 reported greater shape concerns than individuals without binge-eating behavior or binge eating disorder, respectively. Lastly, one study reported a trend for a link between night eating and negative components of body image 58.

Two studies 30, 64 examined the relationship between post-operative body image and history of abuse. Both studies reported general body image improvements post-surgery; however, significant differences in body image scores did not emerge when comparing two groups (sexual abuse history vs. no sexual abuse history 64) or when comparing three groups (childhood sexual abuse, other maltreatment, and no maltreatment 30).

Three studies 41, 57, 65 compared body image scores between bariatric patients and a control group. Adami et al. 65 compared three groups: post-bariatric patients, individuals with obesity without a history of bariatric surgery, and healthy subjects without obesity from a university setting. Overall, bariatric patients had lower body disparagement scores than individuals with obesity. Among bariatric patients with adult-onset obesity, some measures of body image were comparable to the healthy comparison group, while those with early-onset obesity had greater body dissatisfaction scores. In a longitudinal study, Adami et al. 41 compared 30 bariatric patients and a control group matched for gender and age. Although general body image improvements were observed among the bariatric surgery group, only some aspects of body image ratings were comparable to those of the control group.

Finally, one small treatment outcome study randomized post-operative bariatric surgery patients to either acceptance and commitment therapy or treatment-as-usual for disordered eating, body image, and quality of life. Body image was assessed before treatment, after six weeks of treatment 23, and six months following the end of treatment 24. The acceptance and commitment treatment group reported significant improvements in body image and weight concerns at the post and six-month follow-up assessments; while the treatment-as-usual group reported improvements in weight concerns from pre-treatment to the six-month follow-up.

Studies examining body image among bariatric surgery patients pre- or post-BCS

Table 2 summarizes the BCS literature, including study design and timeframe, sample characteristics, bariatric and BCS type, body image measures, and relevant findings. A total of 15 identified articles examined body image among post-bariatric adults pre- or post-BCS with a range of methodological designs. Six studies utilized a cross-sectional design, seven utilized a longitudinal design, and two involved scale development. Of the six cross-sectional studies, two studies consisted of post-bariatric surgery patients seeking BCS (n=35 66 and n=36 67), while four included post-BCS patients (n=10 68; n=10 69; n=20 70; and n=62 71). Two of the cross-sectional studies 69, 71 compared more than two study groups cross-sectionally (i.e., pre-bariatric surgery patients, post-bariatric surgery patients without BCS, and post bariatric surgery patients who underwent BCS 71). A variety of bariatric surgery samples were studied with some studies including more than one bariatric surgery type 67, 70, 71 and time since bariatric surgery ranged from 6–38.71 months. Of the seven longitudinal studies, BCS sample sizes were small, ranging from 18–47, and follow-up assessments ranged from three 72 to 61 months (range: 32–83 months 73) months post-BCS. Three studies had a six-month follow-up assessment 74–76 while two had a 12-month follow-up assessment 77, 78. A range of bariatric surgeries were reported in the longitudinal designs including a single bariatric surgery (i.e., gastric banding 78; biliopancreatic diversion 75; gastric bypass 77) or more than one bariatric surgery type 72, 73, 76. Several body contouring procedures following bariatric surgery were reported with abdominoplasty appearing to be the most common. Studies focusing on scale development 21, 22 did not indicate bariatric or BCS type.

Table 2.

Summary of articles reporting body image results among bariatric surgery patients before or after body contouring surgery

| Study (ref) by Design and Year |

Study Design Timeframe Group Description (if indicated) |

Sample Characteristics Gender: n or % Race: n or % Age: Mean±SD years Post-WLS BMI: Mean±SD kg/m2 |

WLS typea

· n included if > 1 procedure BCS type |

Body Image Measures ·Subscales |

Summary of Relevant Body Image Findings Response Rate (cross-sectional design) or Retention Rate (longitudinal design) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pavan (2013) | Cross-sectional · Time since WLS: NI 2 groups: 1. Post-WLS seeking BCS 2. Control (matched BMI and demo-graphics) |

N=35 1. n=35 2. n=33 Gender: 1. Female: 30; 2. Female: 23 1. Male: 5; 2. Male: 10 Race: NI Age: 1. 45.51±11; 2. 41.51±9.1 Post-WLS BMI: 1. 30.17±3.37 |

Bariatric restrictive procedures | BSQ | WLS group had higher BSQ scores than controls. A significantly higher number of WLS patients had moderate or high concerns with shape than the control group. Response rate: 50% |

| Pavan (2017) | Cross-sectional · Time since WLS: NI 2 groups: 1. Post-WLS seeking BCS 2. Control (matched BMI and demo-graphics) |

N=36 1. n=36 2. n=21 Gender: 1. Female: 28; 2. Female: 14 1. Male: 8; 2. Male: 7 Race: NI Age: 1. 42.44±10.6; 2. 40.76±13.73 Post-WLS BMI: 1. 28.77±3.05 |

Sleeve: · 52.78% Band: · 22.22% |

BUT: Italian version |

BCS group reported more past plastic surgeries than controls (36.1% vs. 9.5%) BCS group reported significantly higher scores on Weight Phobia, Body Image Concerns, Avoidance, Depersonalization, Global Severity Index, and Positive Symptom Distress Index Global Severity Index was suggestive for “disease” (>1.2) for BCS group, but not for controls (<1.2). Response rate: NI |

| Menderes (2003) | Cross-sectional · Time since WLS: 27.2 months |

N=11 Gender: Female: 7 Male: 4 Race: NI Age: 37.4 Post-WLS BMI: 34.4 |

Vertical banded gastroplasty Abdominoplasty=11 Reduction mammoplasty=3 Lateral thigh lift=2 Gynecomastia=3 Medial thigh lift=1 Liposuction=3 |

DAS | Of 38 post-WLS patients, 11 patients underwent 23 different plastic surgery interventions. The most frequently performed operation was abdominoplasty. Body image improved after BCS. Response rate: 90.9% |

| Pecori (2007) | Cross-sectional 4 groups: 1. Pre-WLS 2. >2 years post-WLS 3. >2 years post-WLS seeking BCS 4. >2 years Post-WLS and >1 year post-BCS |

N=60 1. n=20 2. n=20 3. n=10 4. n=10 Gender: Female=60 Male=0 Race: NI Age: Overall NI Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI. Post-WLS BMI by groups ranged from 28.2±1.7 (post-BCS) to 31.2±4.5 (post-WLS) |

Biliopancreatic diversion Leg or arm lift=8 Abdominoplasty=7 Mastoplasty=5 Torsoplasty=2 |

BUT | BUT scores were lower post-WLS. Post-WLS patients requesting cosmetic surgery had similar BUT scores to pre-WLS patients and had higher body uneasiness than post-WLS who did not seek cosmetic surgery. Those who had cosmetic surgery had lower body uneasiness scores than pre-WLS patients and post-WLS patients seeking cosmetic surgery. Response rate: NI |

| de Zwaan (2014) | Cross-sectional 3 groups: 1. Pre-WLS 2. Post-WLS, but no BCS 3. Post-WLS and BCS · Time since WLS: 37.8-49.8 months |

N=393 1. n=79 2. n=252 3. n=62 Gender: Overall NI Race: Overall NI Age: Overall NI Age by groups ranged from 41.63±10.40 to 47.97±9.93 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI Post-WLS BMI by groups ranged from 32.46±6.07 to 34.46±7.31 |

Bypass · n=175 Sleeve gastrectomy · n=71 Band · n=63 Other WLS · n=4 Abdominoplasty=55 Thigh lift=15 Breast lift=10 Lower back=7 Arms=6 Buttocks=4 Upper back=1 |

MBSRQ: German version · 10 subscales |

Post-WLS groups reported better MBSRQ scores on 8/10 subscales than the pre-WLS group. BCS group reported better MBSRQ Appearance Evaluation (AE), Body Areas Satisfaction (BAS), and lower Self-Classified Weight (SCW) than post-WLS group without BCS, despite similar BMI; but no differences for 7/10 subscales. Compared post-abdominoplasty to non-BCS post-WLS group who were dissatisfied with abdomen. · After abdominoplasty, BCS group reported better MBSRQ AE, BAS, and SCW. Post-BCS, scores on MBSRQ-AE, Health Evaluation, Illness Orientation, BAS, Overweight Preoccupation, and SCW did not reach norms, but AO, Fitness Evaluation, Fitness Orientation, and Health Orientation did reach norms. Response rate: NI |

| Al-Hadithy (2014) | Cross-sectional 2 groups: 1. Post-WLS · Time since WLS: M=19.6 months 2. Post-BCS Time since WLS: M=38.7 months |

N=68 1. n=48 2. n=20 Gender: Female=44 Male=24 Race: NI Age: Age: 51 Post-WLS BMI: Overall NI Post-WLS BMI by groups ranged from 31.40 to 36.71 |

Restrictive WLS · n=38 Malabsorptive WLS · n=30 Abdominoplasty=24% Brachioplasty=19% Mastopexy=19% Interim abdominoplasty=9% Fleur-de-lys abdominoplasty=9% Lower body lift=5% Thigh lift=5% Mammaplasty=5% Neck reduction=5% |

DAS | Best results were observed in patients who had undergone BCS following restrictive WLS. The authors reported statistically significant improvement in DAS scores, although did not report description of body image analyses or statistical values. Response rate: 90.7% |

| Song (2006) | Longitudinal Pre-BCS: · Baseline Post-BCS: · 3 months · 6 months · Time since WLS: M:20.5 months |

N=18 Gender: Female=16 Male=2 Race: NI Age: 46±10 Post-WLS BMI: 29.4 |

WLS Type NI Abdominal contouring of panniculectomy or cosmetic abdominoplasty=18 Additional BCS=11 |

BISA CBIA PBIA PBSQOL |

Body image improved following BCS. Body image satisfaction improved in only areas that underwent BCS, and this change resulted in increased overall body satisfaction. Self-perception based on current body image silhouettes changes post-BCS. Self-perception of appearance did not change. Retention: 3 months: 100%, 6 months: 72% |

| Stuerz (2008) | Longitudinal Pre-BCS: · Baseline Post-BCS: · 3 months · 12 months · Time since WLS: NI |

N=34 Control group: Post-WLS without BCS: n=26 Gender: Female: 30 Male: 4 Race: NI Age: 37.1±9.3 Post-WLS BCS BMI: 27.1±5.1 Post-WLS Control BMI: 27.9±3.7 |

Band Abdominoplasty |

BPQ · Attractiveness Strauss and Appelts’ Questionnaire for Assessing One’s Body |

Compared to the control group, the post-BCS group reported significant improvements in the body image attractiveness/self-esteem subscale. At 12 months post-BCS, 8 (23.5%) had a second BCS procedure. Retention: 91.2% |

| Bracaglia (2011) | Longitudinal Pre-WLS: · Baseline Post-WLS: · 24 months Post-BCS: · 6 months |

N=47 Gender: Female: 40 Male: 7 Race: NI Age: 41.55±9.48 BMI post-WLS: 31.28±9.35 |

Biliopancreatic diversion Abdominoplasty=11 Abdominoplasty & mastopexy=7 Arm lift=7 Abdominoplasty & arm lift=6 Mastopexy & arm lift=6 Mastopexy=5 Abdominoplasty, mastopexy, & thigh contouring=5 |

BAT | High BAT body dissatisfaction scores pre-WLS. Post-BCS, body image improved but did not reach norms. Post-BCS, only patients experiencing mastopexy, alone or with arm lift, scored within normal range for BAT scores. When three or more plastic surgery procedures were performed, all patients showed BAT scores within the normal range. Retention: NI |

| Koller (2013) | Longitudinal Pre-BCS: · Baseline Post-BCS: · 6 months |

N=27 Gender: Females=25 Males= 2 Race: NI Age: 39.9±10.9 Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass · n=16 Band · n=11 Circumferential body lift |

FBeK | Post-BCS, FBeK subscales attractiveness and self-confidence, as well as insecurity and uneasiness, improved significantly, while accentuation of one’s body and sensibility remained unchanged. Retention: NI |

| Grieco (2016) | Longitudinal Pre-BCS: · Baseline Post-BCS: · 3 months |

N=30 Gender: Females: 22 Male: 8 Race: NI Age: 50.5 Post-WLS BMI: 31.6 |

Bypass · n=13 Band · n=8 Sleeve gastrectomy · n=6 Other · n=3 Abdominoplasty |

BIA-O Figure Ratings: Evolution of the Standard Stimulating Figure Tests |

Post-BCS, patients reported slimmer body image perception based on the figure ratings. Retention: NI |

| Song (2016) | Longitudinal (2 cohorts) 1. Pre-WLS · Baseline Post-WLS · 6 months · 12 months · 24 months 2. Pre-BCS · Baseline Post-BCS · 6 months · 12 months |

N=216 1.WLS n=175 2.BCS n=41 Gender: NI Race: NI Age: NI Post-WLS BMI: NI |

Bypass Panniculectomy=32 Belt lipectomy=3 Lower body lift=2 Upper body lift=2 Breast reduction=2 |

MBSRQ | All MBSRQ subscales significantly improved after WLS except for Overweight Preoccupation; however, retention rates for the WLS group were extremely poor. After BCS, Appearance Evaluation, Appearance Orientation, Body Areas Satisfaction, and Self-Classified Weight improved significantly, but Overweight Preoccupation did not. Retention: 1. WLS: 6 months: 9.1% 12 months: 10.9% 24 months: 2.3% 2. BCS: 6 months: 75.6% 12 months: 65.9% |

| Vierhapper (2017) | Longitudinal Pre-BCS: · Baseline Post-BCS: · 32-83 months · Time since WLS: |

N=40 Gender: Female=40 Male=0 Race: NI Age: 40.9±10.3 Post-WLS BMI: 27.6±3.6 |

Bypass · n=32 Band · n=4 Lifestyle change · n=4 Lower body lift |

FBeK FKB-20 |

FBeK: Scores for attractiveness and self-confidence improved post-BCS, but did not reach norms. The other three subscales, accentuation of own body, insecurity and uneasiness, and sexual discomfort did not change post-BCS. FKB-20: “Dismissive Body Rating” improved significantly after BCS, but remained worse than normative data of healthy female students. FKB-20: 'Vital Body Dynamics' decreased significantly after BCS, signifying that realization of power, fitness, and health was worse after BCS and worse than data from healthy female students. Pre-operative problems like eczema, shame, and difficulties with sport activities and clothes fitting were significantly improved after BCS. 62% wished for further BCS Retention: 72.5% |

| Danilla (2016) | Scale Development | Phase 1: n=16 pre- and post-BCS Phase 2: 1) 1029 general population 2) cohort before BCS and 3 months after BCS 3) cohort 1 and 3 years post-BCS Phase 3: n=34 Test-retest 2-4 weeks after BCS All surgery demographics split by: - before surgery: n=55 - after surgery: n=37 - before and after surgery: n=17 |

NI Unclear whether all post-BCS patients had a history of WLS |

Phase 2 Body-QOL: 120 items · Satisfaction with body · Sex life · Self-esteem and social performance · Physical symptoms |

In surgical group, all scores improved significantly from pre-BCS to 3 months post-BCS. Patients who did not desire BCS scored better than patients who desired BCS. Patients with a history of BCS scored better than control group regardless of desire to have BCS. In WLS patients, pre- and post- scores were lower than in BCS patients, but the improvement before and after surgery was equal between groups. Post-WLS patients scored lower on all domains than BCS patients. Response Rate or Retention: NI for all phases |

| Klassen (2016) | Scale Development | 1. Both pre- and post-WLS asked to complete surveys at baseline, 1 week later, and 6 months later 2. Post-BCS patients 3. Exploring or seeking BCS and those who had BCS: Only those with history of WLS asked to complete Physical Scale and Symptoms checklist 4. Patients in weight loss program and collagen stimulation treatment Demographics by country |

NI | Body-Q · Appearance · Health-Related Quality of Life · Experience of healthcare |

The pre-WLS group reported lower (poorer) body image scores than the post-BCS group. Participants with greater excess skin reported lower (poorer) body image scores than participants with minimal excess skin. Response Rate or Retention: Overall NI |

Outside the two scale development studies 21, 22, over 10 different types of body image measures were used, none of which were psychometrically validated among bariatric surgery patients. Two new body image measures, the Body-QOL and the Body-Q were developed specifically for BCS patients. The Body-QOL (20-items) focuses on body image in several domains including satisfaction, sex life, self-esteem, social performance, and physical symptoms, while the Body-Q (148-items) assesses body image features in addition to other domains (i.e., treatment by medical staff).

Across the varied body image measures, individuals with a history of bariatric surgery seeking BCS reported higher body image dissatisfaction than the general population 66 and a non-surgical control group matched on BMI and demographic variables 67. Individuals who underwent BCS reported improvements in various body image indices compared to post-bariatric patients who did not undergo BCS 68–70, 74, 76–78 including improvements in appearance evaluation, body area satisfaction, and physical functioning, even after adjusting for weight loss and time since surgery 71. Despite undergoing BCS, however, some patients still report dissatisfaction following BCS 71. For example, 27.2% (n=15) continued to report feeling “very dissatisfied to dissatisfied” following abdominoplasty and 40% (n=6) reported feeling “very dissatisfied or dissatisfied” following a thigh lift. Interestingly, none reported dissatisfaction following breast lift (n=10). In addition, patients reported continued dissatisfaction related to non-contoured areas 74. Accordingly, one study found that 23.5% of BCS patients with a history of bariatric surgery underwent a second BCS operation for another area by the second follow-up of the study and all recommended BCS following bariatric surgery 78. When using a well-established body image measure that captures several body image domains (the MBSRQ), only a few body image indices significantly improved among post-BCS patients, namely appearance evaluation, body area satisfaction, and self-classified weight domains, based on both cross-sectional 71 and longitudinal 77 designs. Thus, it may be that certain aspects of body image improve following BCS while others do not. Evidence from one longitudinal study also suggests that body image scores are comparable to norms after three or more BCS procedures are performed or following mastopexy 75.

Discussion

This review systematically examined research on body image following bariatric surgery. Overall, findings from both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies suggest general improvements in body image occur following bariatric surgery. Some studies, however, suggest that certain aspects of body image do not improve post-operatively or do not reach norms. Of note, the majority of studies did not investigate concerns related to excess skin and BCS following bariatric surgery. In addition, eating pathology, such as binge eating, night eating, and loss of control eating, appears to be related to greater body image dissatisfaction post-surgery. The literature is mixed regarding the relationship between weight outcomes and changes in body image. The mixed literature may perhaps be related to methodologic factors including, for example, the variety of body image measures used which tap different aspects of body image (i.e., cognitive, affective, behavioral, or perceptual aspects). It may be that only certain aspects of body image (i.e., body dissatisfaction, body distortion, or body disparagement) generally improve post-surgically.

Discrepant body image findings may also be related to concerns regarding excess skin following substantial weight loss. Despite the high rates of excess skin and associated concerns, very few studies examined body image and excess skin concerns following bariatric surgery and subsequent BCS. The types of BCS were quite varied, with body contouring in the abdominal region being the most common procedure performed. Greater attention to body image concerns related to excess skin and BCS following bariatric surgery is needed. Overall, it appears that BCS helps improve body image for the specific targeted regions, but not necessarily other regions.

It is also important to note that very little is known about adolescent body image following bariatric surgery. Two small studies found clinically significant body image improvements within the first post-operative year 25, 26. Further longitudinal research is needed to better understand the durability of these improvements over time, particularly considering that adolescence is a prime time to develop body image concerns and related eating-disorder psychopathology. Lastly, excess skin concerns and desire for BCS among adolescents are still unknown.

Overall, these results need to be considered cautiously given that the data comprising this literature represents low-level evidence. There was great variation in standards of reporting (i.e., demographic and weight variables) and small sample sizes. For example, nearly half of the studies had a post-operative sample size of less than 50. Approximately half of the cross-sectional and longitudinal studies did not report response rates and retention rates, respectively. Of those that reported retention, retention rates varied considerably across different studies, underscoring relatively high attrition, albeit a few notable exceptions with good retention at least through the earlier follow-up points 3, 26, 45, 50, 51.

Based on conducting this systematic review, we offer several recommendations for future research in this area. First, prospective studies of adolescents and adults are warranted to determine the durability of body image improvements over time. Most studies assessed patients through the first two years post-bariatric surgery and few studies prospectively measured body image following bariatric surgery and subsequent BCS. In addition, prospective studies may help elucidate the relationship between various body image indices, weight outcomes, and associated clinical features. Second, the next generation of research in this area should be conducted with greater methodological rigor and precision when reporting sample characteristics, such as race and BMI over time, and retention/attrition rates. There was tremendous variation in standards and ways of reporting, making direct comparisons difficult. Third, the majority of studies focused on primarily White women and future research with more diverse groups is needed to examine potential sex, ethnic, and racial differences. The mixed findings may be due, in part, to combining various groups (i.e., men and women, or individuals from different racial or ethnic backgrounds). In fact, none of the studies examined sex and racial differences in body image following bariatric surgery. Additionally, it will be important to investigate potential cross-cultural and geographic variations in body image concerns post-bariatric surgery to elucidate the needs of diverse groups. Fourth, more sophisticated analyses should be conducted to better understand the relationships among eating, body image, and weight loss in this group. Moreover, such analyses may help detect protective factors related to body image changes over time. Fifth, operationally defining the body image construct measured (i.e., body dissatisfaction, body distortion, etc.) and developing appropriate, tailored measures specific to the unique needs of this population (i.e., related to excess skin), as opposed to general satisfaction measures or body image measures created for eating disorder populations, may aid in our understanding of the complexity of body image changes following bariatric surgery. Finally, rigorous research and high-level data in this area may help inform insurance policy coverage for subsequent body contouring procedures following bariatric surgery.

Clinically, we offer the following recommendations. Given the low-level evidence for body image improvements following bariatric surgery, coupled with patients’ desire for subsequent body contouring procedures, we encourage targeted psychoeducation and assessment of body image concerns throughout the bariatric surgery process, both before and after bariatric surgery. Psychoeducation should consist of realistic expectations regarding weight loss 79, potential changes in body shape, body contouring options, and potential barriers to BCS. In addition, assessment of various components of body image concerns should be monitored over time. As observed in non-surgical populations 6, various features of body image dissatisfaction may be a signal for greater eating-disorder psychopathology, which could ultimately impact long-term weight loss outcomes following bariatric surgery 3.

In conclusion, this review highlights the need for more rigorous research to better understand the complexities of body image following bariatric surgery and BCS. There is a paucity of research that examines the multidimensional elements of body image following bariatric surgery, particularly related to excess skin and subsequent body contouring procedures. Despite reports indicating general improvements in body image following bariatric surgery, careful examination of the literature indicates a much more complex and varied picture related to excess skin, body contouring surgery, and various body image indices. The next wave of body image research in this area should identify which BCS interventions and for whom (which patients) produce the most benefit following bariatric surgery.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by NIH grant R01 DK098492. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- BCS

Body Contouring Surgery

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- QOL

Quality of Life

- MBSRQ

Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire

References

- 1.Stuerz K. The impact of abodminoplasty after massive weight loss: a qualitative study. Ann Plast Surg. 2013; 71: 549–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013; 273: 219–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devlin MJ, King WC, Kalarchian MA, White GE, Marcus MD, Garcia L, et al. Eating pathology and experience and weight loss in a prospective study of bariatric surgery patients: 3-year follow-up. Int J Eat Disord. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White MA, Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Masheb RM, Marcus MD, Grilo CM. Prognostic Significance of Depressive Symptoms on Weight Loss and Psychosocial Outcomes Following Gastric Bypass Surgery: A Prospective 24-Month Follow-Up Study. Obes Surg. 2015; 25: 1909–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cash TGPT Body image; A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lydecker JA. Form and Formulation: Examining the Distinctiveness of Body Image Constructs in Treatment-Seeking Patients with Binge-Eating Disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson RE, Latner JD, Hayashi K. More than just body weight: The role of body image in psychological and physical functioning. Body Image. 2013; 10: 644–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawaoka T, Barnes RD, Blomquist KK, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Social anxiety and self-consciousness in binge eating disorder: associations with eating disorder psychopathology. Compr Psychiatry. 2012; 53: 740–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hrabosky JI, White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH, Grilo CM. Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire for bariatric surgery candidates. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008; 16: 763–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Libeton M, Dixon JB, Laurie C, O’Brien PE. Patient motivation for bariatric surgery: Characteristics and impact on outcomes. Obesity Surgery. 2004; 14: 392–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitzinger HB, Abayev S, Pittermann A, Karle B, Kubiena H, Bohdjalian A, et al. The prevalence of body contouring surgery after gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2012; 22: 8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitzinger HB, Abayev S, Pittermann A, Karle B, Bohdjalian A, Langer FB, et al. After massive weight loss: patients’ expectations of body contouring surgery. Obes Surg. 2012; 22: 544–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Ertelt TW, Marino JM, Sarwer DB, Thompson JK, et al. The desire for body contouring surgery after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2008; 18: 1308–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giordano S, Victorzon M, Koskivuo I, Suominen E. Physical discomfort due to redundant skin in post-bariatric surgery patients. J Plast Reconstr Aes. 2013; 66: 950–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott A, Johnson J, Pusic AL. Satisfaction and Quality-of-Life Issues in Body Contouring Surgery Patients: a Qualitative Study. Obesity Surgery. 2012; 22: 1527–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heddens CJ. Body contouring after massive weight loss. Plast Surg Nurs. 2004; 24: 107–15; quiz 16–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coulman KD, MacKichan F, Blazeby JM, Owen-Smith A. Patient experiences of outcomes of bariatric surgery: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Obes Rev. 2017; 18: 547–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright RW, Brand RA, Dunn W, Spindler KP. How to write a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007; 455: 23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris JD, Quatman CE, Manring MM, Siston RA, Flanigan DC. How to Write a Systematic Review. Am J Sport Med. 2014; 42: 2761–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009; 62: 1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Alderman A, Soldin M, Thoma A, Robson S, et al. The BODY-Q: A Patient-Reported Outcome Instrument for Weight Loss and Body Contouring Treatments. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016; 4: e679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danilla S, Cuevas P, Aedo S, Dominguez C, Jara R, Calderon ME, et al. Introducing the Body-QoL(R): A New Patient-Reported Outcome Instrument for Measuring Body Satisfaction-Related Quality of Life in Aesthetic and Post-bariatric Body Contouring Patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016; 40: 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weineland S, Arvidsson D, Kakoulidis TP, Dahl J. Acceptance and commitment therapy for bariatric surgery patients, a pilot RCT. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2012; 6: e1–e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weineland S, Hayes SC, Dahl J. Psychological flexibility and the gains of acceptance-based treatment for post-bariatric surgery: six-month follow-up and a test of the underlying model. Clin Obes. 2012; 2: 15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratcliff MB, Eshleman KE, Reiter-Purtill J, Zeller MH. Prospective changes in body image dissatisfaction among adolescent bariatric patients: the importance of body size estimation. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2012; 8: 470–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeller MH, Reiter-Purtill J, Ratcliff MB, Inge TH, Noll JG. Two-year trends in psychosocial functioning after adolescent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2011; 7: 727–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neven K, Dymek M, leGrange D, Maasdam H, Boogerd AC, Alverdy J. The effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on body image. Obes Surg. 2002; 12: 265–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinzl JF, Lanthaler M, Stuerz K, Aigner F. Long-term outcome after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity. Eat Weight Disord. 2011; 16: e250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O’Brien PE. Depression in association with severe obesity: changes with weight loss. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 163: 2058–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH. Relation of childhood sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment to 12-month postoperative outcomes in extremely obese gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2006; 16: 454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hrabosky JI, Masheb RM, White MA, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH, Grilo CM. A prospective study of body dissatisfaction and concerns in extremely obese gastric bypass patients: 6- and 12-month postoperative outcomes. Obes Surg. 2006; 16: 1615–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH, Grilo CM. The prognostic significance of regular binge eating in extremely obese gastric bypass patients: 12-month postoperative outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006; 67: 1928–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Panfilis C, Cero S, Torre M, Salvatore P, Dall’Aglio E, Adorni A, et al. Changes in body image disturbance in morbidly obese patients 1 year after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2007; 17: 792–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Grazing and loss of control related to eating: two high-risk factors following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008; 16: 615–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munoz D, Chen EY, Fischer S, Sanchez-Johnsen L, Roherig M, Dymek-Valentine M, et al. Changes in desired body shape after bariatric surgery. Eat Disord. 2010; 18: 347–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ortega J, Fernandez-Canet R, Alvarez-Valdeita S, Cassinello N, Baguena-Puigcerver MJ. Predictors of psychological symptoms in morbidly obese patients after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012; 8: 770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Teufel M, Rieber N, Meile T, Giel KE, Sauer H, Hunnemeyer K, et al. Body image after sleeve gastrectomy: reduced dissatisfaction and increased dynamics. Obes Surg. 2012; 22: 1232–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melero Y, Ferrer JV, Sanahuja A, Amador L, Hernando D. Psychological changes in morbidly obese patients after sleeve gastrectomy. Cir Esp. 2014; 92: 404–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neff KJ, Chuah LL, Aasheim ET, Jackson S, Dubb SS, Radhakrishnan ST, et al. Beyond weight loss: evaluating the multiple benefits of bariatric surgery after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2014; 24: 684–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wimmelmann CL, Lund MT, Hansen M, Dela F, Mortensen EL. The Effect of Preoperative Type 2 Diabetes and Physical Fitness on Mental Health and Health-Related Quality of Life after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. J Obes. 2016; 2016: 3474816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adami GF, Meneghelli A, Bressani A, Scopinaro N. Body image in obese patients before and after stable weight reduction following bariatric surgery. J Psychosom Res. 1999; 46: 275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O’Brien PE. Body image: appearance orientation and evaluation in the severely obese. Changes with weight loss. Obes Surg. 2002; 12: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Hout GCM, Fortuin FAM, Pelle AJM, van Heck GL. Psychosocial functioning, personality, and body image following vertical banded gastroplasty. Obesity Surgery. 2008; 18: 115–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Hout GCM, Hagendoren CAJM, Verschure SKM, van Heck GL. Psychosocial Predictors of Success After Vertical Banded Gastroplasty. Obesity Surgery. 2009; 19: 701–07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Moore RH, Eisenberg MH, Raper SE, Williams NN. Changes in quality of life and body image after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010; 6: 608–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thonney B, Pataky Z, Badel S, Bobbioni-Harsch E, Golay A. The relationship between weight loss and psychosocial functioning among bariatric surgery patients. American Journal of Surgery. 2010; 199: 183–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White MA, Kalarchian MA, Masheb RM, Marcus MD, Grilo CM. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery patients: a prospective, 24-month follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010; 71: 175–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lanza. Effect of psycho-pedagogical preparation before gastric bypass. Education Patient Therapist. 2013; 5: 101–06. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gordon PC, Sallet JA, Sallet PC. The impact of temperament and character inventory personality traits on long-term outcome of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2014; 24: 1647–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarwer DB, Spitzer JC, Wadden TA, Rosen RC, Mitchell JE, Lancaster K, et al. Sexual functioning and sex hormones in men who underwent bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015; 11: 643–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarwer DB, Spitzer JC, Wadden TA, Mitchell JE, Lancaster K, Courcoulas A, et al. Changes in sexual functioning and sex hormone levels in women following bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014; 149: 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nickel F, Schmidt L, Bruckner T, Buchler MW, Muller-Stich BP, Fischer L. Influence of bariatric surgery on quality of life, body image, and general self-efficacy within 6 and 24 months-a prospective cohort study. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2017; 13: 313–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leombruni P, Piero A, Dosio D, Novelli A, Abbate-Daga G, Morino M, et al. Psychological predictors of outcome in vertical banded gastroplasty: a 6 months prospective pilot study. Obes Surg. 2007; 17: 941–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madan AK, Beech BM, Tichansky DS. Body esteem improves after bariatric surgery. Surg Innov. 2008; 15: 32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Masheb RM, Grilo CM, Burke-Martindale CH, Rothschild BS. Evaluating oneself by shape and weight is not the same as being dissatisfied about shape and weight: A longitudinal examination in severely obese gastric bypass patients. Int J Eat Disord. 2006; 39: 716–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matini D, Ghanbari Jolfaei A, Pazouki A, Pishgahroudsari M, Ehtesham M. The comparison of severity and prevalence of major depressive disorder, general anxiety disorder and eating disorders before and after bariatric surgery. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2014; 28: 109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mirijello A, D’Angelo C, Iaconelli A, Capristo E, Ferrulli A, Leccesi L, et al. Social phobia and quality of life in morbidly obese patients before and after bariatric surgery. J Affect Disorders. 2015; 179: 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morrow J, Gluck M, Lorence M, Flancbaum L, Geliebter A. Night eating status and influence on body weight, body image, hunger, and cortisol pre- and post- Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) surgery. Eat Weight Disord. 2008; 13: e96–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guisado JA, Vaz FJ, Alarcon J, Lopez-Ibor JJ, Rubio MA, Gaite L. Psychopathological status and interpersonal functioning following weight loss in morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2002; 12: 835–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramalho S, Bastos AP, Silva C, Vaz AR, Brandao I, Machado PP, et al. Excessive Skin and Sexual Function: Relationship with Psychological Variables and Weight Regain in Women After Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2015; 25: 1149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Larsen JK, van Ramshorst B, van Doornen LJ, Geenen R. Salivary cortisol and binge eating disorder in obese women after surgery for morbid obesity. Int J Behav Med. 2009; 16: 311–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Conceicao E, Bastos AP, Brandao I, Vaz AR, Ramalho S, Arrojado F, et al. Loss of control eating and weight outcomes after bariatric surgery: a study with a Portuguese sample. Eat Weight Disord. 2014; 19: 103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ivezaj V, Kessler EE, Lydecker JA, Barnes RD, White MA, Grilo CM. Loss-of-control eating following sleeve gastrectomy surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buser AT, Lam CS, Poplawski SC. A long-term cross-sectional study on gastric bypass surgery: impact of self-reported past sexual abuse. Obes Surg. 2009; 19: 422–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adami GF, Gandolfo P, Campostano A, Meneghelli A, Ravera G, Scopinaro N. Body image and body weight in obese patients. Int J Eat Disord. 1998; 24: 299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pavan C, Azzi M, Lancerotto L, Marini M, Busetto L, Bassetto F, et al. Overweight/obese patients referring to plastic surgery: temperament and personality traits. Obes Surg. 2013; 23: 437–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pavan C, Marini M, De Antoni E, Scarpa C, Brambullo T, Bassetto F, et al. Psychological and Psychiatric Traits in Post-bariatric Patients Asking for Body-Contouring Surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017; 41: 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]