Abstract

While the legitimacy of medical treatments is more and more questioned, one sees a paradoxical increase in nonconventional approaches, notably so in psychiatry. Over time, approaches that were considered valuable by the scientific community were found to be inefficacious, while other approaches, labelled as alternative or complementary, were finally discovered to be useful in a few indications. From this observation, we propose to classify therapies as orthodox (scientifically validated) or heterodox (scientifically not validated). To illustrate these two categories, we discuss the place, the role, the interest, and also the potential risks of nonconventional approaches in the present practice of psychiatry.

Keywords: alternative and complementary medicine, evidence-based medicine, heterodox, orthodox, psychiatry

Abstract

Si bien la legitimidad de los tratamientos médicos se cuestiona cada vez más, se observa un aumento paradójico en las aproximaciones no convencionales, especialmente en la psiquiatría. Con el tiempo, se descubrió que las aproximaciones que la comunidad científica consideraba valiosas eran ineficaces, mientras que otros enfoques, etiquetados como alternativos o complementarios, se descubrieron finalmente como útiles en algunas indicaciones. A partir de esta observación, se propone clasificar las terapias como ortodoxas (validadas científicamente) o heterodoxas (no validadas científicamente). Para ilustrar estas dos categorías, se discute el lugar, el papel, el interés y también los riesgos potenciales de las aproximaciones no convencionales en la práctica actual de la psiquiatría.

Abstract

Tandis que la légitimité des traitements médicaux est de plus en plus mise en question, on constate une augmentation paradoxale des approches non conventionnelles, notamment en psychiatrie. Avec le temps, des approches qui étaient considérées de valeur par la communauté scientifique se sont révélées inefficaces, tandis que d'autres, étiquetées comme alternatives ou complémentaires, ont été décrites comme efficaces dans quelques indications. À partir de cette observation, nous proposons de classer les traitements soit comme orthodoxes (validés scientifiquement) soit comme hétérodoxes (non validés scientifiquement). Pour illustrer ces deux catégories, nous commentons la place, le rôle, l'intérêt et aussi les risques potentiels des approches non conventionnelles dans la pratique actuelle de la psychiatrie.

Introduction

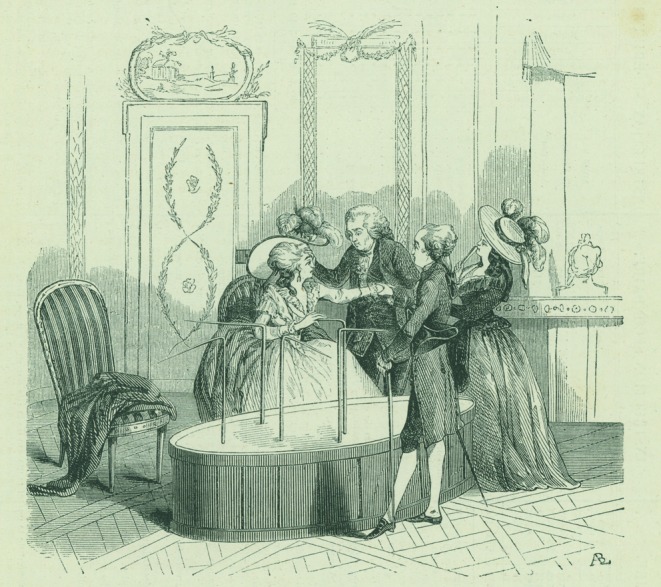

The power of human imagination has led our ancestors to consider the influence of celestial bodies, spirits, and gods on the horror of diseases and death. Over millennia, priests, shamans, sacred men, and medicine men helped their peers by predicting their fate and cure on the basis of various rituals, such as examining animal intestines or ingesting diverse compounds. The Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) wrote of interactions between planets, plants, and animals, and he considered God as the central magnet of all things. The physician Franz Mesmer (1734-1815) extended Kircher's idea into application of the vital principle as a therapy for psychiatric symptoms for which there was then no therapy (Figure 1). In the United States, members of the Fox family declared by 1888 that their mediumnity was in fact a hoax, which did not stop the appeal of exchanging messages with the dead; only later in the 20th century did spiritism fall into some disrepute.

Figure 1. Franz Mesmer's tub according to a 1784 French engraving The tub (baquet) contained immersed bottles with magnetized water and iron fillings. Iron rods coming out of the tub were directed towards body parts and harmonica music was played while the patients held hands. Mesmer, who had fled from Vienna to Paris, was considered a genius by some and a charlatan by others. Eight members from the Académie de Medicine and the Académie des Sciences demonstrated that the tingling, trembling, tears, and even convulsions observed in persons who knew they were being magnetized were absent when subjects were magnetized while being unaware of it.

Frontiers between recognized treatments and charlatanism have long been a theme of discussion, and Louis of Jaucourt (1704-1779) wrote about this in the Diderot and d'Alembert Encyclopedia:

The desire to live is a passion so natural and so strong it is not surprising that those who in health have little or no faith in the skillfulness of an empiric with secrets, appeal nonetheless to this false physician in grave and serious illnesses, the same as those who are drowning cling to the smallest branch. They persuade themselves of having received aid, each time that skilled men did not have the effrontery to promise them a certainty.

Nowadays, complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) are presented as safe, effective and affordable treatments, also for mental health problems. We discuss this category of approaches in mental care, excluding from this paper the role of traditional treatments in countries with little medical staff, where other traditional healers take care of the burden of disorders.

Definition

CAMs are diagnostic techniques and treatment practices outside mainstream and standard health care. It is said that complementary approaches are added to standard health care, while alternative ones are substitutes for it, a somewhat spurious non-operational nuance, because adding an alternative approach to a conventional one would make it complementary by definition. Integrative medicine is the combination of standard health care with CAMs, either simultaneously or successively. Some CAMs can be a priori labeled as charlatanism, ie, as useless approaches sold by charismatic healers to vulnerable customers.

We propose two qualifiers related to CAMs as well as to standard health care. We label as orthodox (from the Greek ortho meaning right or straight path and doxa meaning belief) those techniques that have adequately, ie, scientifically and rationally, been demonstrated to be efficacious and useful. The history of discoveries of orthodox methods starts with the first schools of medicine in the early Mediterranean world, even earlier elsewhere. We label heterodox those techniques that have been demonstrated as useless for diagnosis (iridology, astrology, etc) or as equivalent to placebo for treatment (homeopathy, prayer for others, etc) or for which there is no reason to hope for efficacy over that of placebo (protection through crystals, auriculotherapy, aura therapy, Ho'oponopono, etc). Some heterodox approaches date back thousands of years. According to our proposed qualifiers, CAMs can be orthodox in given indications: biofeedback, neurofeedback, hypnosis, virtual reality techniques, mindfulness relaxation, omega 3 fatty acids, etc, while previously conventional approaches have been given up (frontal lobotomy, insulin coma, meprobamate), and many nowadays off-label prescriptions can be seen as heterodox.

Clinical illustration 1. This 45 year-old patient is in ambulatory care because of severe depression. He had been doing clerical work for 15 years but lost this job because of conflicts with his boss. Psychotherapy, antidepressants, and augmentation treatment were without benefit. He consulted another medical doctor who ordered tests measuring neurotransmitters and their metabolites, amino acids, and immune globulins, and prescribed unusual treatment such as micronutrition and hormones. This gave the patient a feeling of being well taken care of, although his depression did not improve.

Practitioners of heterodox approaches have attempted to have their techniques accepted as orthodox, for example orgone machines by Wilhelm Reich, primal therapy by Arthur Janov, orthomolecular psychiatry by Carl Pfeiffer. Treatment of depression under hallucinogens, psychoanalysis, narco-analysis, and psychosurgery shifted from being heterodox to orthodox, only to be later considered again as heterodox or possibly so. Some approaches are difficult to label as either orthodox or heterodox because of lack of clinical studies or because of the unusual aspect of the method: pet-assisted therapy, visual and acoustic brain stimulation machines, fecal microbiote transplant in psychiatry, etc.

Multiplicity of complementary and alternative medicines

CAM techniques are many and can be classified as mainly biologically based (phytotherapy, diets, massage) or addressing the mind/body relations (relaxation, techniques of energies balancing, therapeutic action at a distance). Clients searching for relief from psychological suffering can use, to quote a partial alphabetical list of CAMS, acupressure, acupuncture, animal-based therapy, anthroposophy, atlas repositioning, astrology, aura therapy, auriculotherapy, Ayurveda, bracelets and medals, Coué method, cryogenic whole body therapy at minus 100°C, crystals and minerals, DNA healing over the phone, energy techniques based on auras or chakras, essential oils, family constellation therapy, homeopathy, massages, osteopathy, pendulum dowsing, reiki, relaxation, regression towards previous lives, sensory deprivation, special shoe soles, talking to angels, touch therapy, urotherapy, etc, Within a given CAM category, one can obtain diverse effects: Saint Gabriel incense helps with making the right decisions, while Padre Pio incense decreases stress and anxiety. CAMs can be associated, for example in phyto-astrology or lithochakra-numerology.

Reasons for choosing CAMs

Reasons put forward by persons who choose CAMs are many: natural treatments are better than chemical ones, psychotropic medications are not systematically effective and induce side effects, pharmaceutical industries aim only at their own profit, physicians consider functional symptoms as not being diseases, physicians do not spend enough time with patients, conventional treatment is not well reimbursed, wellness is a higher goal than the mere decrease in symptoms, viewing a person as a whole leads to a more human society, modern science bridges with ancient wisdom, the normal state of Mother Nature is health, CAMs and other heterodox approaches generate hope. People are induced into using CAMs by the fact that science education is neglected, by the existence of national and international conferences on CAMs, and by the lack of state regulations and recommendations.

Suggestion is another reason for choosing CAMs. It leads to reassurance and empowerment of the client: the therapy will work because the CAM practitioner says so, and because he or she indicates that it restores harmony and balance within bodily and mental energies. This is often felt as psychologically more comfortable than a medicine driven by technology, even if centered on the patient, with its probabilistic predictions based on the complexity of clinical status, familial medical history and paraclinical testing (epigenome, metabolome, proteome, genome, etc) and, in psychiatry, neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging. Even this knowledge does not suffice to build certainty and uncertainty remains an arduous concept for patients and doctors to acknowledge.1 With CAMs, empowerment arises from the ease of understanding simple causes and mechanisms that are not mingled: energy channels (acupuncture), toxic substances (detoxification), energy transfer (subtle bodies therapy), the same cures the same (homeopathy), the state of internal organs is projected on the ear, the feet, or the iris (auriculotherapy, foot massage, iridology), the precise choice of the therapeutic substance (bioresonnance), etc, Some CAMs are said to be efficacious for many, if not almost all, ailments, and this totalizing approach is also reassuring.

Clinical illustration 2. This young man has just been diagnosed with bipolar II disorder. His psychiatrist did not propose a clear cause for the onset of the disorder A naturopath, firmly explained the link between the symptoms and a family loss in the patient's early childhood. He offered a treatment based on herbs, in order to balance vital energy.

Confirming the opinion of the majority2 is yet another reason to choose CAMs: one reads that homeopathy is not superior to placebo, but people hear friends tell their success story of having benefited from it. Also, some medical doctors become practitioners of CAMs.

Clinical illustration 3. This 45-year-old woman works as a surgeon in emergency and other hospital services. Because she felt a lack of human relations with her patients, she decided to compensate for this by acquiring competence in the fields of acupuncture and homeopathy, two CAMs that she then offered to hospitalized patients.

Personality, but also culture and education play a role in the tendency towards belief in the paranormal: immigrants from Africa to Europe might combine witchcraft and modern medicine knowledge to explain their symptoms. All these reasons explain that anxious or depressed persons more often use CAMs than orthodox treatments,3 and this has a high financial cost.4

Mechanisms of action

Several mechanisms of action are non-specific and common to all CAMs. The first one is suggestion,5 asserted by the success of the French pharmacist Coué's method6 of conscious autosuggestion exemplified by his sentence “every day, in every way, I am getting better and better,” by the number of self-help books, by the benefits of placebo, and by the idea that doctors, professors, or gurus (in the orthodox and heterodox domains respectively) are powerful therapists. A second common mechanism of action is giving the patient enough time to feel listened to and understood as an individual. A third mechanism common to several CAMs is the induction of a restful state during the sessions.

There are potentially specific mechanisms of action for some CAMs. The pharmacological effects and modes of action of phytotherapy extracts or purified substances have been recently studied using the same technologies as for pharmaceutical products discovery: high-throughput screening, biomarkers identification and system biology approach. Animal models of behavioral and biochemical changes have also been used for the study of CAMs' mechanisms of action. As laboratory studies or animal studies are easier or less costly than clinical trials, there is an abundance of such protocols on CAMs, for example the effect of acupuncture on neuropeptide Y in the basolateral amygdala of maternally separated rats,7 or its influence on brain networks activation in humans. In summary, there are many fundamental laboratory and too few clinical studies of CAMs, a regrettable situation, somewhat akin to that with conventional therapies. These fundamental studies have, however, not yet established well-defined specific mechanisms by which a given CAM might act.

Efficacy

Most CAMS have not been studied with placebo-controlled trials and selected randomized patients. When such studies were done, the results were often equal to placebos. Also, results about a given CAM were more positive in countries where it was already widely used.8 There are no studies on the associated administration of CAMs, and few studies on the addition of CAMs to orthodox treatments. Some studies show astonishing results: while trials of praying for another person generally showed no health effect9 or were criticized for their methodology,10 there is one study where North Americans who prayed for 199 Korean women undergoing in vitro insemination doubled the fecundation rate, from 26% to 50% of success.11 Sectarian religious groups are particularly prone to the diffusion of miracle cures, and televangelists shout: “Depression, in the name of Jesus, go away... go away... demons go away.” The fact that a CAM dates back hundreds of years is quoted as an argument in favor of efficacy. Should black bile theory still be accepted, just because Hippocrates described it? Or bloodletting, outside of cases of hemochromatosis? Simple protocols can test hypotheses underlying given CAMs, for example by testing whether therapeutic touch practitioners are capable of identifying whether or not there is a person behind a thin opaque screen.12

CAMs' efficacy is often alluded to on the basis of single cases. On the internet and/or other media, one has access to many stories where a CAM practitioner has interrupted years of a patient's suffering from bipolar disorder, depression, or schizophrenia just with a naturopathic treatment like homeopathy. These are indications either that the CAM prescribed was efficacious for that person in that situation, or that the syndrome improved spontaneously. Some CAMs are considered efficacious in the absence of controlled clinical trials: yoga, adequate diet, physical exercise might help in cases of depression. Thus, adding these CAMs to a conventional treatment might be useful. This does not apply to other CAMs such as micronutrition, homeopathy, or bioresonnance. Despite the lack of evidence for efficacy of many CAMs, a Beijing Declaration was adopted in 2008 to call on WHO Member States and other stakeholders to “take steps in order to integrate traditional medicine and CAMs into national health systems.” This would, at least in part, represent accepting the use of impure placebos, ie, placebo not limited to a pharmacologically inert substance.

Finally, outside of the realm of CAMs, many nonmedical interventions are very beneficial, such as prevention of addictions, school bullying, child maltreatment, and others; studies on these primary prevention interventions are of paramount relevance to mental health.

Side effects

Many CAMs imply a form of magic world, with immediate diagnoses, powerful transfers of energy, a chemically purified body, etc. These ideas go as far as believing that entities from advanced planets take care of us, or that gurus survive without food by just being exposed to light. Thus, a first side effect of most CAMs is a facilitation of paranormal beliefs, an alienation from rational thinking. This side effect is of little medical or psychiatric consequence for healthy people, but it can deter fragile or sick persons from the necessary orthodox diagnostic and treatment approaches.

Clinical illustration 4. This woman was dying from pancreatic cancer and she only received homeopathic medicine from her medical doctor until her son asked another doctor to prescribe opioids.

The dark side of suggestion is the nocebo effect, potent to the point of leading to voodoo deaths.13 Opposing innocuous CAMs to the danger of orthodox medications and treatment increases the nocebo effect of these approaches.

Clinical illustration 5. This 50-year-old man refused to take an anxiolytic and inquiry into the reasons for his refusal led to the discovery of his profound dislike of chemical medicine and to the fact that he had been noncompliant with the oral oncologic medication for weeks.

The goal of achieving harmony between mind and body, between flows of energy, common to several CAMs, can present itself in non-realistic terms.

Clinical illustration 6. A 16-year-old boy was treated for a delusional disorder, including the belief in his psychokinesis. His parents rejected medical help for weeks, because their own kinesiologist had assured them that a few persons are indeed endowed with the ability of psychokinesis, of moving objects around without touching them.

The cost of treatment becomes a side effect when inefficacious CAMs are expensive, There are also side effects specific to given CAM. Acupuncture can lead to hematoma pneumothorax, chylothorax, and perforation of abdominal organs.14 Psychotic breakdowns or dissociative states can occur after dialogues with the dead, travel towards former lives, hypnosis, deep relaxation through meditation and massages. Yoga can lead to physical trauma. CAMs practitioners often have insufficient training about efficacy and side effects.

Clinical illustration 7. The mood swings of this 40-year-old man with bipolar I disorder were stabilized with psychotropic drugs. Despite good professional training, he had been unemployed for several years. In order to get a job, he asked a coach for assistance. The latter convinced him of the uselessness of drugs, telling him that he should only rely on himself. The patient kept seeing the coach until his hospitalization for severe mania.

Clinical illustration 8. This 30-year-old European woman travels to India for an Ayurvedic treatment. A severe acne breakout develops while there: she is told that this is the sign of toxin removal. Back in Europe, she is proposed isotretinoin by a dermatologist, not a wise prescription because of her medical history of severe delusional depression.

CAMs practitioners, aside from the caricatural behaviors illustrated in several of the above clinical illustrations, also give wise advice such as getting enough exercise, avoiding unhealthy food, taking time to meditate; this has few side effects, aside from some people becoming obsessed by their cautious life habits.

Sources and quality of information

There exist few valuable sources of information outside of state-funded institutions such as the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) in the United States, the National Health Service (NHS) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in Great Britain. Through the NCCIH readers have free internet access to the CAMs they are interested in, the syndrome they wish to know about, and how to treat it if they choose CAMs. The information is presented in a manner that assumes that the reader is capable of understanding clinical trials, meta-analyses, and evidence-based medicine (EBM). Collaborators of the Canadian CANMAT have made recommendations as to the use of CAMs in cases of depression.15 The French Academy of Medicine recognizes acupuncture, osteopathy, tai-chi, and hypnosis as being of possible value in given medical backgrounds, and homeopathy of absolutely no value, The Skeptic's Dictionary, available through the Internet, offers an extended list of critical analyses of CAMs that can help readers in their choices. The 2012 Flying Publisher Guide to Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments in Psychiatry is of high quality and freely accessible on the Internet, as are the many comments from the Society for Science-Based Medicine pertaining to CAMs regulations in the United States.

The Cochrane Collaboration reviews and the clinical trials of CAMs mentioned in PubMed are a valuable source of information. Their content gives indications where CAMs could be useful, but mostly illustrates the need for more studies, with the frequent occurrence of series of words such as “may be effective,” “larger more powered trials are needed,” “methodological flaws limiting definite conclusions,” “positive findings are reported... but there is currently insufficient research evidence for firm conclusions to be drawn,” etc.

Not all sources of information are of quality, even when of official nature. For example, the Internet portal Evidence Based Acupuncture mentions the 2003 World Health Organization Report on Acupuncture, with the 28 syndromes and disorders for which acupuncture was considered proven through controlled trials to be an effective treatment, including renal colic or malposition of the fetus. Except depression, there was no psychiatric syndrome in this first list, but in the next list of 63 conditions where “therapeutic effect has been shown but for which further proof is needed,” one finds alcohol, cocaine, heroin, opium and tobacco dependence or detoxification, fibromyalgia, male sexual dysfunction, premenstrual syndrome, schizophrenia, Tourette syndrome, and vascular dementia. The conclusions from the above review seem quite optimistic, despite the term “evidence-based” being in its title.

Many journals for the general public participate in the diffusion of favorable opinions about CAMs. In order to adapt their message in a science-oriented culture, their journalists publish side-by-side articles dealing with real science (such as precise descriptions of neuroimaging results in psychiatric disorders) and articles on angels having saved a child's life. This mix of truthful and bizarre information blurs the distinction between peer-reviewed information guaranteed by a self-corrective social system, and irrational belief in paranormal events, to which a proportion of CAMs refer. One finds misleading statements in the media that “the reality of mediums' interventions and powers are now proven by research in university centers” or that “human consciousness is explained by quantum physics.” The French astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842-1925) is a historical example of a man of science having had irrational ideas: he asserted that the discovery of radio and telephone would lead to confirming telepathy. A few well-known contemporary scientists are fond of unproven ideas and they publish books, host television shows, and have internet portals. The internet offers information of dubious quality concerning both heterodox and orthodox approaches, and this is the price for the otherwise justified concept of information transparency.

Clinical illustration 9. This 60-year-old man with a university education and training spends hours searching the Internet about treatments for his mood disorder, and participates in discussion on the Internet. He confronts his psychiatrist with all this information and asks him to comment in detail on other medications and why he should or should not try them. He thinks that psychiatrists work mainly for pharmaceutical companies, and that there exist potentially useful but unknown compounds outside mainstream prescriptions.

There are institutions dedicated to the control of false and misleading advertisement, such as the Federal Trade Commission in the United States. In France, Miviludes works towards protecting citizens against sectarian religious groups and debunking falsehoods in CAMs. Readers who wish to read critical facts about CAMs might consult the Internet portal of Professor Edzard Ernst (1948-), an emeritus professor of complementary medicine who became critical of CAMs.16

All sources of information, and those on CAMs are no exception, confront readers with the uneasy task of evaluating the veracity of what is described. CAMs practitioners assume that patients are able to decide for themselves. (This applies also to orthodox approaches and to the promise of revolutionized medicine thanks to microtechniques and artificial intelligence).17 Once a belief is established, the discovery of facts contradicting it (ie, knowledge rather than conviction) does not automatically lead to a new belief. This is true of declarations about the inefficacy of CAMs such as homeopathy, as well as of acceptance of scientific discoveries.18

Conclusion

Decades ago, lots of people considered CAMs as quackery or fraud. This has now changed and the present diffusion of CAMs, with hundreds of methods and thousands of practitioners in occidental countries, is neither a sufficient nor a satisfactory argument to accept CAMs as a regular approach in treating psychiatric syndromes, despite the empathy and the good intentions of many CAMs practitioners to alleviate human suffering.

There are four major explanations why CAMs are more largely used than justified by the controversies about their clinical efficacy. First, appreciation of occult sciences and magical ideas isn't limited to the dark ages of sorcery: it also represents an appealing option in times when society is felt to be dominated by science and reason, and paralogical thinking might presently be among the substitutes for the decrease in traditional religiosity. Second, practicing CAMs is a developing means of financial gains. The Internet has facilitated these gains by offering greater access to consumers, and CAMs consultations by telephone are billed or offered after receipt of a check. Third, some members of the medical profession, even within university hospitals, endorse CAMs. Patients in given oncology units systematically receive hypnosis to decrease their anxiety and depression, or the phone number of the person who will “make the secret,” ie, say special incantations that will prevent side effects of oncologic treatments. In fact, patients prefer hospitals where CAMs are also offered.19 A fourth reason for the diffusion of CAMs is the limitation of efficacy in heterodox approaches in psychiatry and other specialties.

Our recommendation to distinguish orthodox from heterodox approaches in health care offers an operational criterium for a classification that enables placing each CAM along a continuum from clearly heterodox to clearly orthodox, ie, an incentive towards a wider use of the methodology of EBM for the evaluation of CAMS. Most of the work in view of the orthodox/heterodox CAMs classification remains to be done, because of the lack of relevant previous clinical research studies,20 the methodological issues with these studies, and the lack of registration requirements and practice regulations for CAMs. It is necessary to identify CAMs for which there is compelling evidence of their uselessness, to disseminate these facts, and to inform the public in what cases they are paying for a method akin to a placebo. With CAMs that might be somewhat superior to placebo, studies should address the questions of numbers and frequency of sessions, role of the experience of the therapist, relative efficacy towards conventional approaches, and consequences of associating CAMs with conventional treatments.

The task and challenge within the coming decade should be to draw frontiers between acceptable CAMs and charlatanism, ie, to clearly differentiate truly inefficacious CAMs from the few that have, or might have, useful therapeutic or preventive effects at least slightly above placebo effects. Moreover, studies should be set up to evaluate the best modalities for the transfer of objective information about CAMs, to explore how patients understand EBM when their medical doctor prescribes homeopathy, when the insurance reimburses this prescription, and when CAMs practitioners describe their treatments within simplistic overarching mechanisms.

On the condition that these different categories of studies could be carried out, better state regulations as to CAMs teaching, certification, and practice might be set up. In short, the requirements of EBM should be applied to CAMs' evaluation. All this will be arduous, because of financial interests linked to CAMs and because of the not too fashionable, to say the least, promotion of reasonable doubt in the search for veracity.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Pierre Schulz, Former Head, Unit of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Department of Mental Health and Psychiatry, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.

Vincent Hede, Mood Disorders Unit, Department of Mental Health and Psychiatry, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhise V., Rajan SS., Sittig DF., et al. Defining and measuring diagnostic uncertainty in medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;33(1):103–115. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4164-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asch SE. Opinion and social pressure. Scientific American. 1955;193(5):31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC., Soukup J., Davis RB., et al. The use of complementary and alternative therapies to treat anxiety and depression in the United States. Arn J Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):289–294. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purohit MP., Zafonte RD., Sherman LM., et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and expenditure on complementary and alternative medicine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(7):e870–e876. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baudoin C. Suggestion and Autosuggestion. New York, NY: Dodd, Mead, and Co; 1922. First published in French in 1920 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coué E. Self Mastery Through Conscious Autosuggestion., New York, NY: American Library Service; 1922. First published in French in 1920 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park HJ., Chae Y., Jang J., Shim I., Lee H., Lim S. The effect of acupuncture on anxiety and neuropeptide Y expression in the basolateral amygdala of maternally separated rats. Neurosic Lett. 2005;377(3):179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickers A., Goyal N., Harland R., et al. Do certain countries produce only positive results? A systematic review of controlled trials. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radin J., Schlitz M., Baur C. Distant healing intention therapies: an overview of the scientific evidence. Glob Adv Health Med. 2015:67–71. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2015.012.suppl. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrade C., Radhakrishnan R. Prayer and healing: a medical and scientific perspective on randomized controlled trials. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(4):247–253. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cha KY., Wirth DP. Does prayer influence the success of in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer? Report of a masked, randomized trial. J Reprod Med. 2001;46(9):781–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosa L., Rosa E., Sarner L., Barrett S. A close look at therapeutic touch. JAMA. 198;279(13):1005–1010. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.13.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez EA. Voodoo and sudden death: The effects of expectations on health. Transcultural Psychiatry Res Rev. 1982;19(2):75–92. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J., Shang H., Gao X., Ernst E. Acupuncture-related adverse events: a systematic review of the Chinese literature. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(12):915–921. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.076737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravindran AV., Balneaves LG., Faulkner G., et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Adults with Major Depressive Disorder: Section 5. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):576–87. doi: 10.1177/0706743716660290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinhh S., Ernst E. Trick or Treatment. Alternative Medicine on Trial., London, UK: Bantam Press. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Topol E. The Patient Will See You Now. The Future of Medicine Is in Your Hands. New York, NY: Basic Books. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn TS. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago, IL; University of Chicago Press. 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carruzzo P., Graz B., Rodondi PY., Michaud PA. Offer and use of complementary and alternative medicine in hospitals of the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13756. doi: 10.4414/smw.2013.13756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorski DH., Novella SP. Clinical trials of integrative medicine: testing whether magic works? Trends Mol Med. 2014;20(9):473–476. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]