Abstract

Objective

For the patients with pathologic T2 N0 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the extent of lymph node (LN) removal required for survival is controversial. We aimed to explore the prognostic significance of examined LNs and to identify how many nodes should be examined.

Methods

We reviewed 549 patients who underwent pulmonary or pneumonectomy surgery or plus lymphadenectomy who were confirmed as T2 stage and LN negative by postoperative pathological diagnosis. According to Martingale residuals of the Cox model, the patients were classified into four groups by the number of examined LNs (1–2 LNs, 3–7 LNs, 8–11 LNs, and ≥12 LNs). Kaplan–Meier analysis and Cox regression analysis were used to evaluate the association between survival and the number of examined LNs.

Result

Compared with the 1–2 LNs, 3–7 LNs, and 8–11 LNs groups, the survival was significantly better in the ≥12 LNs group. The 5-year cancer-specific survival rate was 60.5% for patients with 1–2 negative LNs, compared with 68.7%, 72.6%, and 78.4% for those with 3–7, 8–11, and >11 LNs examined, respectively. The 7-year cancer-specific survival rate was 52.9% for patients with 1–2 negative LNs, compared with 63.7%, 63.8%, and 70.8% for those with 3–7, 8–11, and >11 LNs examined, respectively (P=0.045). There was a significant drop in mortality risk with the examination of more LNs. The lowest mortality risk occurred in those with 32 or more LNs examined. Multivariate analysis showed that age and the number of examined LNs were strong independent predictors of survival.

Conclusion

The number of examined LNs is a strong independent prognostic factor. Our study demonstrates that patients with T2 N0 NSCLC should have at least 12 LNs examined and that the results of this study may provide information for the optimal number of resected LNs in surgery.

Keywords: number of resected lymph nodes, non-small cell lung cancer, survival outcome

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of tumor-related deaths.1 Even though early stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients may be cured by surgery, the postoperative survival rates are relatively low and the 5-year survival rate is ∼50%–60%.2,3 Lymph node (LN) assessment is the strongest predictor of postoperative long-term survival.4 In clinical practice, the eighth edition of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM classification is widely applied in the staging of NSCLC. However, it does not regulate the lowest number of LNs that need to be resected for various stage patients. Both carcinoma of esophagus and breast carcinoma have a definite number of resected LNs required in surgery. For NSCLC, some small institutional studies have reported the relationship between increased number of LN removed and survival.5,6 However, the extent of LN removal required to affect survival is controversial. Examining more LNs may avoid micrometastatic LNs, increase the possibility of accurate staging, and increase survival time.7 There is evidence of a large amount of heterogeneity in LN assessment.8,9 As such, the possibility of identifying LN metastasis may be attributed to the quantity of LNs examined. The greater the quantity of resected LNs, the less likely that N1 or N2 patients is wrongly diagnosed as N0.

As we know, the probability of LN metastasis is significantly increased with the raise of T stage and the extent of LN removal required varies with N stage.10,11 As such, in our study, we specifically studied patients with T2 N0 NSCLC. The purpose of our study was to identify the quantity of LNs related to the largest improvement in survival, which we propose as the first-rank number required to accurately identify the absence of nodal metastasis in T2 stage NSCLC patients.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

We reviewed consecutive NSCLC patients who underwent pulmonary lobectomy or pneumonectomy plus lymphadenectomy and who had confirmed LN negative by postoperative pathological diagnosis based on the eighth edition of the UICC TNM system at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou (Guangdong, People’s Republic of China) between June 1999 and September 2009. Patients were included in our study according to the following eligibility criteria: patients who had underwent pulmonary lobectomy or pneumonectomy plus lymphadenectomy and diagnosed as T2N0M0 NSCLC at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, confirmed R0 resection.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patients with small cell lung cancer, preoperative chemotherapy, or radiotherapy; 2) patients who have distant metastasis, second cancer; and 3) patients who died within 30 days of surgery and those with deficient histological information. Finally, 549 patients were enrolled in our study.

The follow-up results, clinical data, and cause of death were obtained from a review of medical records and the follow-up department of the hospital. All of the patients were treated according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.

All nodal material was separated from the specimen by the surgeon at the end of the procedure. Every LN was labeled according to their site of origin based on Mountain and Dresler mediastinal and pulmonary LN map; then, the pathologist measured them in three dimensions and analyzed them. One section of all the LNs was routinely examined histopathologically. Sometimes, we cut the serial sections from node area with the purpose of better confirming diagnosis and staging.

Follow-up

All patients had follow-up after surgery every 4 months for the first and second year, every 6 months for the third to fifth year and once a year thereafter. The evaluation includes chest X-ray, chest computed tomography scan, brain MRI, abdominal ultrasonography, and pertinent tumor markers. Cancer-specific survival was used to assess the connection between the number of negative LNs and prognosis to control for unrelated causes of death. We defined the time from diagnosis until the date of death, the end of follow up, or the date that the survival information was collected as the survival time. The follow-up date was updated to January 2017.

Statistical analysis

We used chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact tests to evaluate the differences in baseline clinical parameters between different groups. To compare differences in the survival rate between groups, Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank test was used. Cox regression multivariate analysis was used to test for the variables that were significant in the univariate analysis. Relative risks are presented with their 95% CIs. We defined the cutoff points of the number of examined LNs according to Martingale residuals of the Cox model with the software SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

The patient consent was written informed consent, and that this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institute Research Medical Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center granted approval for this study.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 549 patients were enrolled in the cohort. Based on Martingale residuals of the Cox model, the cutoff points of the number of examined LNs was identified as 1–2, 3–7, 8–11, ≥12 LNs. The relationship between the characteristics of patients and their tumors and the quantity of examined LNs was show in Table 1. Tumor location, surgical approach, whether existed bronchia invasion, and age influenced the number of examined LNs significantly. The patients with right-side tumors, young age, and no bronchia invasion tended to have more resected LNs. Based on the number of negative LNs, no significant differences existed between the distribution of gender, histological type, tumor size, visceral pleura invasion, or smoking status and the four different classifications.

Table 1.

Distribution of clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients in the four categories, as classified by the number of examined LNs

| Variable | No. of examined nodes (n)

|

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 3–7 | 8–11 | ≥12 | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender | 0.744 | ||||

| Male | 21 (3.8%) | 81 (14.8%) | 80 (14.6%) | 210 (38.3%) | |

| Female | 7 (1.35%) | 28 (5.1%) | 30 (5.5%) | 92 (16.8%) | |

| Age (years) | 0.022 | ||||

| ≤65 | 13 (2.4%) | 74 (13.5%) | 84 (15.3%) | 203 (37.0%) | |

| >65 | 15 (2.7%) | 35 (6.4%) | 26 (4.7%) | 99 (18.0%) | |

| Smoking status | 0.956 | ||||

| Never | 11 (2.0%) | 46 (8.4%) | 43 (7.8%) | 126 (23.0%) | |

| Former | 17 (3.1%) | 63 (11.5%) | 67 (12.2%) | 176 (32.1%) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.984 | ||||

| ≤4 | 21 (3.8%) | 84 (15.3%) | 86 (15.7%) | 235 (42.8%) | |

| >4 | 7 (1.3%) | 25 (4.6%) | 24 (4.4%) | 67 (12.2%) | |

| Tumor location | 0.002 | ||||

| Left | 12 (2.2%) | 48 (8.7%) | 62 (11.3%) | 106 (19.3%) | |

| Right | 16 (2.9%) | 61 (11.1%) | 48 (8.7%) | 196 (35.7%) | |

| Histological type | 0.300 | ||||

| Squamous | 6 (1.1%) | 30 (5.5%) | 31 (5.6%) | 107 (19.5%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 19 (3.5%) | 73 (13.3%) | 66 (12.0%) | 166 (30.2%) | |

| Adenosquamous | 2 (0.4%) | 5 (0.9%) | 11 (2.0%) | 20 (3.6%) | |

| Others | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.4%) | 8 (1.5%) | |

| Visceral pleura invasion | 0.108 | ||||

| Yes | 11 (2.0%) | 67 (12.2%) | 71 (12.9%) | 184 (33.5%) | |

| No | 17 (3.1%) | 42 (7.7%) | 39 (7.1%) | 118 (21.5%) | |

| Bronchia invasion | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (0.5%) | 20 (3.6%) | 22 (4.0%) | 97 (17.7%) | |

| No | 25 (4.6%) | 89 (16.2%) | 88 (16.0%) | 205 (37.3%) | |

| Surgical approach | <0.001 | ||||

| Thoracotomy | 18 (3.3%) | 99 (18.0%) | 95 (17.3%) | 273 (49.7%) | |

| VATS | 10 (1.8%) | 10 (1.8%) | 15 (2.7%) | 29 (5.3%) | |

| Place of tumor relapse | 0.271 | ||||

| Intrathoracic metastases | 2 (1.5%) | 17 (12.7%) | 14 (10.4%) | 41 (30.6%) | |

| Systemic metastases | 4 (3.0%) | 11 (8.2%) | 18 (13.4%) | 27 (20.1%) | |

Abbreviations: LN, lymph node; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

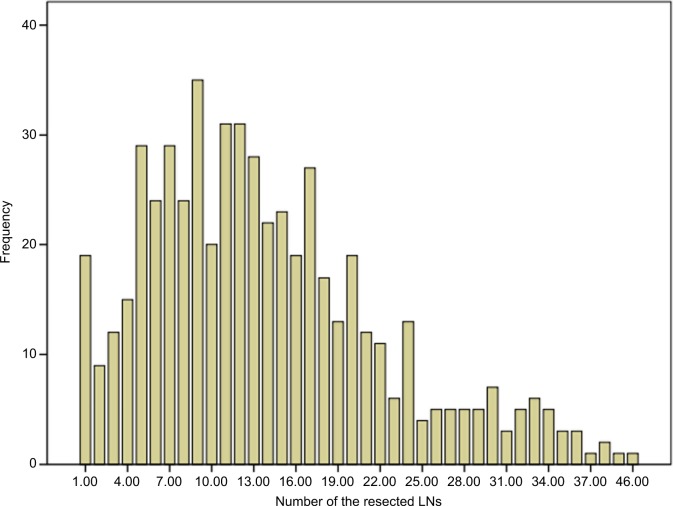

The distribution of the number of LNs in patients is shown in Figure 1. The median number of resected LNs was 12 (range 1–46), and the median number of resected stations was 4 (range 1–9) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the number of resected LNs.

Abbreviation: LN, lymph node.

Table 2.

Resected LNs characteristics

| Variable | Mean (range) | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of LNs resected | 13.84 (1–46) | 549 | |

| 1–2 | 28 | 5.1 | |

| 3–7 | 109 | 19.9 | |

| 8–11 | 110 | 20 | |

| ≥12 | 302 | 55 | |

| N1 nodes resected | 3.65 (0–17) | ||

| N2 nodes resected | 10.16 (0–45) | ||

| Total resected LNs stations | 4.45 (1–9) | ||

| N1 station | 1.30 (0–4) | ||

| N2 station | 3.15 (0–6) |

Abbreviation: LN, lymph node.

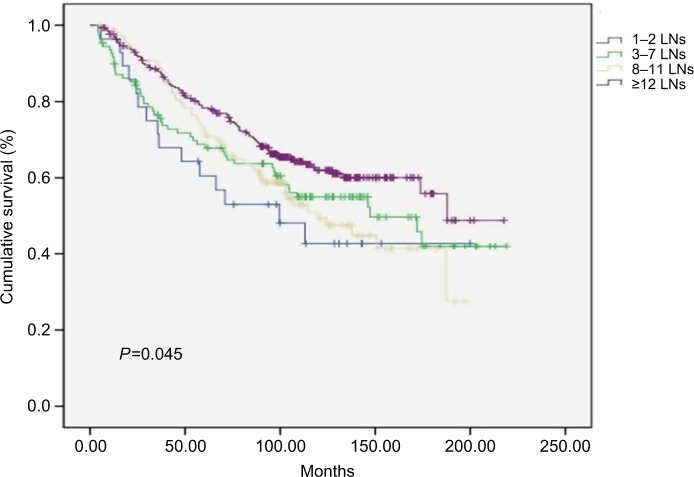

Impact of LN counts on survival

After the minimum of at least 7 years follow-up, cancer-specific survival of the patients with more negative LNs was significantly higher. The rate of 5-year cancer-specific survival was 60.5% for patients with 1–2 negative LNs, compared with 68.7%, 72.6%, and 78.4% for those with 3–7, 8–11, and >11 LNs examined, respectively. The 7-year cancer-specific survival rate was 52.9% for patients with 1–2 negative LNs, compared with 63.7%, 63.8%, and 70.8% for those with 3–7, 8–11, and >11 LNs examined, respectively (P=0.045) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cancer-specific survival curves for four classifications of patients based on the number of the LNs resected in 549 patients (P=0.045).

Abbreviation: LN, lymph node.

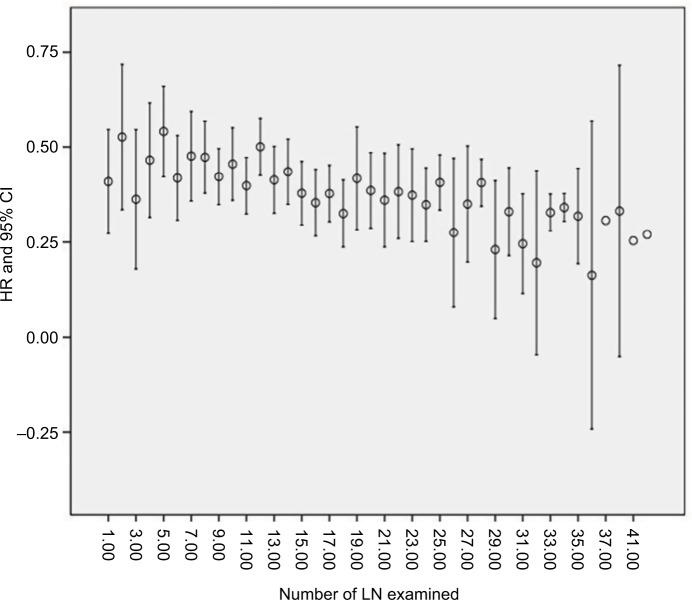

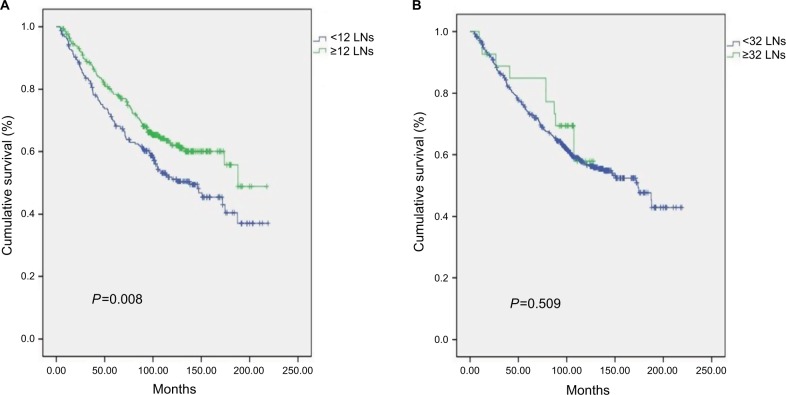

With the increasing number of LN examined, the HR for death decreased sequentially. Until the examination of 32 nodes, it can obtain a maximal benefit. Beyond the examination of 32 LNs, the sequential improvement in the HR for mortality was no longer evident (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Evolution of HR for mortality with the number of LNs resected.

Notes: With the increasing number of LN examined, the HR for death decreased sequentially. Until the examination of 32 nodes, it can obtain a maximal benefit. Beyond the examination of 32 LNs, the sequential improvement in the HR for mortality was no longer evident.

Abbreviation: LN, lymph node.

We carried out univariate survival analysis of variables of all cohorts. It revealed that age, bronchia invasion, and the number of examined LNs were related to cancer-specific survival (P<0.001, P=0.040, and P=0.045, respectively). The number of resected N1, N2, or total LN station was not associated with survival. To further identify whether the number of examined LNs was related to survival, a multivariate Cox regression analysis was used. The results showed that age and the number of examined LNs were strong independent predictors of survival (P<0.001 and P=0.020, respectively). Compared with other groups, the survival was better in the ≥12 LNs group significantly and ≥12 LNs examined reduced significantly the chance of cancer-related mortality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship between the number of examined LNs and cancer-specific survival in univariate and multivariate analysis

| Variable | Number | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|

| |||||

| Gender | 0.093 | ||||

| Male | 392 | ||||

| Female | 157 | 0.771 (0.569–1.045) | |||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | 1.807 (1.382–2.363) | <0.001 | ||

| ≤65 | 374 | ||||

| >65 | 175 | 1.828 (1.399–2.387) | |||

| Smoking status | 0.052 | ||||

| Never | 226 | ||||

| Former | 323 | 1.306 (0.996–1.711) | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.289 | ||||

| ≤4 | 426 | ||||

| >4 | 123 | 1.179 (0.869–1.598) | |||

| Tumor location | 0.995 | ||||

| Left | 228 | ||||

| Right | 321 | 0.999 (0.767–1.302) | |||

| Histological type | 0.349 | ||||

| Squamous | 174 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 325 | 1.162 (0.868–1.556) | 0.314 | ||

| Adenosqumaous | 38 | 1.376 (0.808–2.343) | 0.240 | ||

| Others | 12 | 0.480 (0.117–1.962) | 0.307 | ||

| Visceral pleura invasion | 0.584 | ||||

| No | 216 | ||||

| Yes | 333 | 1.078 (0.823–1.412) | |||

| Bronchia invasion | 0.040 | 0.795 (0.570–1.109) | 0.177 | ||

| No | 407 | ||||

| Yes | 142 | 0.712 (0.513–0.987) | |||

| Differentiation | 0.172 | ||||

| Well or moderate | 333 | ||||

| Poor or undifferentiated | 216 | 1.202 (0.923–1.567) | |||

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.076 | ||||

| No | 459 | ||||

| Yes | 90 | 0.704 (0.476–1.040) | |||

| Number of examined LNs | 0.045 | 0.854 (0.747–0.976) | 0.020 | ||

| 1–2 | 28 | ||||

| 3–7 | 109 | 0.761 (0.427–1.356) | 0.354 | ||

| 8–11 | 110 | 0.803 (0.452–1.424) | 0.452 | ||

| ≥12 | 302 | 0.566 (0.330–0.972) | 0.039 | ||

| Number of examined N1 station | 0.691 | ||||

| ≥3 | 38 | ||||

| <3 | 511 | 1.112 (0.658–1.880) | |||

| Number of examined N2 station | 0.775 | ||||

| ≥3 | 374 | ||||

| <3 | 175 | 1.042 (0.786–1.380) | |||

| Total resected station | 0.830 | ||||

| ≥6 | 146 | ||||

| <6 | 403 | 1.033 (0.771–1.384) | |||

Abbreviation: LN, lymph node.

Identification of optimal LN number

According to above results, we suggest that the optimal number of examined LNs for T2N0 patients is not <12, but that the examination of 32 or more LNs limits any further improvements in nodal staging. Kaplan–Meier analysis and a log-rank test were carried out between <12 LNs and ≥12 LNs, and between <32 LNs and ≥32 LNs. The 5 years cancer-specific survival was 69.5% vs 78.4% and 73.8% vs 84.9%, the 7 years cancer-specific survival was 62.5% vs 70.8% and 66.5% vs 77.2%, the HR (95% CI) was 0.704 (0.541–0.914) and 0.799 (0.410–1.558), the P-values were 0.008 and 0.509, respectively. As such, we confirm this optimal LN number is effective (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(A) Cancer-specific survival curves for 549 patients with <12 LNs and ≥12 LNs resected (P=0.008). (B) Cancer-specific survival curves for 549 patients with <32 LNs and ≥32 LNs resected (P=0.509).

Abbreviation: LN, lymph node.

Discussion

LN status is an important crucial factor of stage and survival in lung cancer patients and it is important to accurately iden tify N stage. The number of examined LN is a measurement that reveals the thoroughness of the examination, and that will judge the probability of finding LN metastases. Previous findings have shown that patients have a better survival rate thanks to the increasing number of examined LNs.11–13 The retrospective studies have demonstrated that the number of resected LNs is related to better OS.14–17 This could be due to various reasons. For example, as the number of LNs examined decreases, the likelihood of missing a positive LN increases and so does the proportion of higher-stage disease patients who are misclassified as lower-stage disease. Also, resecting more negative LNs can decrease the rate of LN micrometastases that cannot be identified by routine histologic examination. This is significant as patients with micrometastases often have a peculiarly high recurrence risk.7,18

The NCCN guidelines suggested that N1 and N2 node resection and mapping (The American Thoracic Society map) (at least three N2 stations sampled or complete lymph-node dissection) should be performed. However, it does not recommend the lowest number of LNs necessary.19 Additionally, the eighth edition of the UICC TNM classification does not indicate the first-rank number of LNs that should be examined in surgery.5 As such, the degree of lymphadenectomy in early-stage NSCLC has been controversial.

The European Society of Thoracic Surgeons guidelines have suggested that the lowest requirements for accurate nodal staging must include minimum six LNs from the hilar and mediastinal stations.20,21 Several studies have also recommended that 11–16 is the optimal number of removed LNs for assessing stage I lung cancer.14,22 Additionally, some reports have determined that examining minimum eight LNs improved survival in pN0 NSCLC.11

Furthermore, three previous population-based studies have demonstrated the relationship between LN examination and survival in patients of pN0 NSCLC. One reported that survival peaked at ∼13–16 LNs, Beyond the examination of 16 LNs, the improvement for survival was no longer evident.14 Another demonstrated that the improvement for outcomes increased with increasing number of LNs examined, with a plateau at “≥11 LNs.”.22 The last one revealed that the resection of 11–15 LNs conferred the minimum HR for death compared with patients with no LN examined.23 Recently, one similar study showed that the examination of nearly 18–20 LNs was optimally related to reduced death risk in patients with resected node-negative NSCLC.24 With regards to N1 and N2 disease, some studies have yielded different conclusions.25–28 However, the variability of the results may be because of the heterogeneous populations and the surgical procedures conducted in the studies.

In our study, we suggest that the examination of ∼12–30 LNs can better reduce the mortality risk in pathologic T2 N0 NSCLC patients. However, the number of resected N1, N2, or total LN station was not associated with survival. This is contrary to recent studies that have indicated that the number of LNs has no significant effect on OS and that have recommended that a complete systematic pulmonary and mediastinal lymphadenectomy should be performed in NSCLC.29,30 This may be because in some LN stations, examining minor LNs alone cannot meet the standard of accurate staging. As such, in our study, we suggest that systematic lymphadenectomy also should have an appropriate resected LN number for different LN stations. Additional studies are needed to validate our findings. There was a significant difference in survival outcome between the <12 LNs and ≥12 LNs group. When the number reached 32, the HR for mortality no longer decreased. However, above results need more evidence to be confirmed. Additionally, our data showed that age and the number of examined nodes were strong independent predictors of survival in multivariate analysis.

In our study, Martingale residual analysis was used to examine the functional form of the covariate under study and identify the cutoff value of the number of examined LNs as 1–2 LNs, 3–7 LNs, 8–11 LNs, and ≥12 LNs. Few previous studies have used this statistical method. We believe that this method can recognize differences of the survival between groups and make our study objectively effective. In contrast to other studies, we only analyzed potential T2 N0 NSCLC patients who uniformly underwent lobectomy plus lymphadenectomy. As such, our results were not confounded by various T stage, positive N1 or N2 LN, and different types of surgery. This is despite the data from the ACOSOG Z0030, which found that there was no survival difference between early stage NSCLC patients who received an elaborate systematic sampling procedure in comparison with those who had mediastinal nodal dissection.31 In summary, our results are relative reliable and can be applied in these patients.

It was inevitable that there were some limitations in our study. For example, it was a retrospective and single-institution research study and our sample size was not larger than population-based studies. However, our study can be a reference for the Chinese population. The other limitation is that the quantity of LNs examined is a simple surrogate for the thoroughness of examination. It may be confounded by fragmentation of the LNs and the standard of lymphadenectomy may need more standardization. However, as we did not find survival differences in the number of resected N1, N2 or total LN station, our study mainly focused on identifying the optimal number of resected LNs. Also, we tried to find the adequate LN dissecting number for pT2N0 patients, but the p staging cannot help surgeons make the right decision during surgery, which restricted the clinical significance of this study.

In conclusion, the number of examined LNs is a strong independent prognostic factor. Our study demonstrates that patients with potential T2 N0 NSCLC following pulmonary lobectomy or pneumonectomy should have at least 12 LNs examined, whereas the discrimination power and efficacy of this guideline for clinical practice should be confirmed by large-scale, prospective clinical study in the future.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No. 2012AA021503). The abstract of this paper was presented at the 24th European Conference on General Thoracic Surgery Conference name The Number of Resected Lymph Nodes is Associated With the Long-Term Survival Outcome in Patients with Pathologic T2a N0 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer as a poster presentation with interim findings.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2137–2150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fry WA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. Ten-year survey of lung cancer treatment and survival in hospitals in the United States: a national cancer data base report. Cancer. 1999;86(9):1867–1876. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991101)86:9<1867::aid-cncr31>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(8):706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osarogiagbon RU. Predicting survival of patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer: beyond TNM. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4(2):214–216. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.03.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Tanoue LT. The new lung cancer staging system. Chest. 2009;136(1):260–271. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471–1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigurdson ER. Lymph node dissection: is it diagnostic or therapeutic? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):965–967. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gephardt GN, Baker PB. Lung carcinoma surgical pathology report adequacy: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of over 8300 cases from 464 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120(10):922–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osarogiagbon RU, Yu X. Mediastinal lymph node examination and survival in resected early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer in the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(12):1798–1806. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31827457db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham AN, Chan KJ, Pastorino U, Goldstraw P. Systematic nodal dissection in the intrathoracic staging of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117(2):246–251. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saji H, Tsuboi M, Yoshida K, et al. Prognostic impact of number of resected and involved lymph nodes at complete resection on survival in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(11):1865–1871. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822a35c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu YC, Lin CF, Hsu WH, Huang BS, Huang MH, Wang LS. Long-term results of pathological stage I non-small cell lung cancer: validation of using the number of totally removed lymph nodes as a staging control. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24(6):994–1001. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(03)00567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang W, He J, Shen Y, et al. Impact of examined lymph node count on precise staging and long-term survival of resected non-small-cell lung cancer: a population study of the US SEER database and a Chinese multi-institutional registry. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(11):1162–1170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.5140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludwig MS, Goodman M, Miller DL, Johnstone PA. Postoperative survival and the number of lymph nodes sampled during resection of node-negative non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2005;128(3):1545–1550. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller SM, Adak S, Wagner H, Johnson DH. Mediastinal lymph node dissection improves survival in patients with stages II and IIIa non-small cell lung cancer. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70(2):358–365. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gajra A, Newman N, Gamble GP, Kohman LJ, Graziano SL. Effect of number of lymph nodes sampled on outcome in patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1029–1034. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doddoli C, Aragon A, Barlesi F, et al. Does the extent of lymph node dissection influence outcome in patients with stage I non-small-cell lung cancer? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27(4):680–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(25):1604–1608. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506203122504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Borghaei H, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 2.2013. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(6):645–653. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Leyn P, Lardinois D, van Schil PE, et al. ESTS guidelines for preoperative lymph node staging for non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Leyn P, Lardinois D, van Schil P, et al. European trends in preoperative and intraoperative nodal staging: ESTS guidelines. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(4):357–361. doi: 10.1097/01.JTO.0000263722.22686.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varlotto JM, Recht A, Nikolov M, Flickinger JC, Decamp MM. Extent of lymphadenectomy and outcome for patients with stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(4):851–858. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ou SH, Zell JA. Prognostic significance of the number of lymph nodes removed at lobectomy in stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(8):880–886. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31817dfced. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osarogiagbon RU, Ogbata O, Yu X. Number of lymph nodes associated with maximal reduction of long-term mortality risk in pathologic node-negative non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(2):385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.09.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukui T, Mori S, Yokoi K, Mitsudomi T. Significance of the number of positive lymph nodes in resected non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1(2):120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nwogu CE, Groman A, Fahey D, et al. Number of lymph nodes and metastatic lymph node ratio are associated with survival in lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93(5):1614–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bria E, Milella M, Sperduti I, et al. A novel clinical prognostic score incorporating the number of resected lymph-nodes to predict recurrence and survival in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2009;66(3):365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonnalagadda S, Arcinega J, Smith C, Wisnivesky JP. Validation of the lymph node ratio as a prognostic factor in patients with N1 nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(20):4724–4731. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riquet M, Legras A, Mordant P, et al. Number of mediastinal lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer: a Gaussian curve, not a prognostic factor. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(1):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeon HW, Moon MH, Kim KS, et al. Extent of removal for mediastinal nodal stations for patients with clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer: effect on outcome. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62(7):599–604. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1360478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darling GE, Allen MS, Decker PA, et al. Randomized trial of mediastinal lymph node sampling versus complete lymphadenectomy during pulmonary resection in the patient with N0 or N1 (less than hilar) non-small cell carcinoma: results of the American College of Surgery Oncology Group Z0030 Trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(3):662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]