Abstract

Motivated by disparate healthy food access in neighborhoods across the US, federal, state, and local initiatives have emerged to develop supermarkets in “food deserts.” Differences in the implementation of these initiatives are evident, including the presence of health programming, yet no comprehensive inventory of projects exists to assess their impact. Using interviews, public databases, and media archives, I collected details (project location, financing, development, health promotion efforts) about all supermarket developments under “fresh food financing” regimes in the US, 2004–2015. In total, I identified 126 projects. Projects have been developed in a majority of states, with concentrations in the mid-Atlantic and Southern California regions. Average store size was approximately 28,100 square feet, and those receiving financial assistance from local sources and New Markets Tax Credits were significantly larger, while those receiving assistance from other federal sources were significantly smaller. About 24 percent included health-oriented features; of these, over 80 percent received federal financing. If new supermarkets alone are insufficient for health behavior change, greater attention to these nuances is needed from program designers, policymakers, and advocates who seek to continue fresh food financing programs. Efforts to reduce rates of diet-related disease by expanding food access can be improved by taking stock of existing efforts.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, programs have been created at all levels of government to improve access to healthy foods by developing supermarkets in “food deserts,” typically disadvantaged communities with low physical access to affordable, acceptable healthy foods (1,2), and that are disproportionately affected by diet-related chronic illnesses (3,4). The constellation of programs to encourage supermarket development in food deserts grew steadily since the creation of the Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative (PA-FFFI) in 2004, which initiated a line of policies that explicitly related access to full-service supermarkets with health disparities (5,6).

Following the lead of PA-FFFI architects, such as The Food Trust (TFT), a food access advocacy nonprofit, and The Reinvestment Fund (TRF), a community development financial institution (CDFI), similar programs emerged nationwide, including the federal Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI). These programs, commonly called “fresh food financing,” require substantial public and/or private financing to overcome start-up constraints (typically hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars), present a substantial investment in underserved neighborhoods with ancillary effects beyond food access (i.e. employment opportunities, tax revenues), and introduce greater quantity and variety of foods than related projects (i.e. corner stores, mobile markets) (7–9).

Because of physical, economic, and political variations between sites, planning processes and development strategies used for specific projects are notably different. Existing health evaluations of new retailers in food deserts provide examples of these differences, as they include a national chain retailer, regional chains developed with city and state incentives, and a cooperative market (10–15). Each has a unique community context; thus, to form expectations of retailers, including those around public health effects, we should first understand how they differ and why it matters.

METHODS

Data Collection

No comprehensive list of fresh food financing projects currently exists. I employed a cross-sectional design to create this database, which required a range of sources (see Table 1). Project inclusion criteria consisted of: 1) funding from a food access-dedicated source, such as HFFI, or described by officials or media as addressing “food access” or “food desert” issues; and 2) built or substantially renovated a food retail outlet; and 3) described as a grocery store or supermarket (i.e. not a corner store). This approach was intended to capture projects beyond those funded by major programs, while narrowing the entire range of food access interventions (i.e. farmers’ markets, corner stores, mobile markets, etc.).

Table 1.

Secondary Data Sources used to Identify Fresh Food Financing Supermarket Projects in the U.S., 2004–2015.

| Type of Data Source | Name | Author | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dedicated “Healthy Food Access” Sources | Healthy Food Access Portal | TRF, TFT, PolicyLink | Database of reports, articles, case studies and other web resources |

| HFFI Grantee Convening Documents | TRF, Healthy Food Access Portal | Self-reported use of HFFI funds | |

| Financing-Based Sources | Novogradac NMTC Database | Novogradac | Self-reported NMTC project locations and allocation amounts |

| CDFI Fund HFFI Awardee List | CDFI Fund | HFFI-NMTC, HFFI-FA recipients | |

| HHS CED Awardee List | HHS | CED recipients | |

| HFFI Grantee List | USDA | Recipients of HFFI funding | |

| Supermarket Industry Sources | Newsletter Archives | Progressive Grocer, Supermarket News, FMI Daily Lead | Daily/weekly food retailing industry newsletters |

| Food Marketing Institute Report | FMI | Short report on industry efforts to expand food access | |

| Newsmedia | National, regional, local news reports | Various outlets | Media coverage of efforts to expand food access |

Abbreviations: HHS, Health and Human Services; CED, Community Economic Development; CDFI, Community Development Financial Institution; PA-FFFI, Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative; CA-FWF, California FreshWorks Fund; NMTC, New Markets Tax Credit; FFRI, Fresh Food Retailer Initiative.

The project database included project location (exact address), date the store opened, its size (in square feet) and number of store employees, and sources of financing. I also classified stores in terms of business structure: large national chains (nationally-recognizable presence, such as Save-a-Lot, Safeway, or Whole Foods), regional chains (several stores in a specific metropolitan region), and local retailers (only one store). Additionally, I noted if store business models were cooperatives (operated under an employee or member-ownership model), nonprofits (did not seek to maximize profits, driven by a social mission), or discount retailers (offered reduced prices and more limited selections). I imported sources into NVivo 10 and coded them according to project(s) described.

Virtual Site Checks

Using Google Street View imagery from 2007–2015, I verified the location and status (completed, uncompleted, closed) of retailers, and identified development types: stand-alone store (unconnected parcel surrounded by surface parking), shopping plaza (accompanied by other retailers and surrounded by surface parking), mixed-used (large development featuring co-located or integrated housing and retail), neighborhood store (retailer in urban area without surface parking lot and embedded on city block), or main street store (storefront on main street with limited parking, high pedestrian access).

Analyses

I generated descriptive statistics for quantitative project characteristics, and two-tailed t-tests (Alpha=5%) using StatPlus (Version 6.0.3) to identify significant differences in means between classes of projects. With ArcGIS 10.0, I mapped projects and classified them by US Census region (20). I identified themes to describe models of financing, development, and health promotion. Data collection and analysis took place from January 2013 to February 2016.

RESULTS

Summary of Federal, State, and Local Fresh Food Financing Programs

Though there were as many combinations of incentives as there are projects (see Table 2), many of the following initiatives served as models for subsequent funding sources; thus, these specific examples may provide a relevant sense of where and how funds are generally directed.

Table 2.

Types of Incentives and Financing used for New Supermarket Development in U.S. Food Deserts, 2004–2014.

| Incentive | Type | Example(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal | New Markets Tax Credit | tax expenditure | (unique incentive) |

| HHS CED Grant | grant | (unique incentive) | |

| CDFI Fund Financial Assistance Award | grant (matching funds required) | (unique incentive) | |

| Community Development Block Grant | locally-administered grant | (unique incentive) | |

| Other Federal redevelopment sources | various | Enterprise Zones, American Recovery and Reinvestment Act | |

| Regional | Large CDFI Program | tax credits, grants, loans | TRF ReFresh |

| State | Fresh Food Financing Program | grants and loans | PA-FFFI, CA-FWF |

| Redevelopment tax credit | tax expenditure | State NMTC Program | |

| Community/economic development grants | grant | PA Keystone Opportunity Zones | |

| Local | Fresh Food Financing Program | grants and loans | New Orleans FFRI |

| Tax abatements | tax expenditure | 10-year tax abatement | |

| Land incentives | lower development burden | Land transfers, parcel assemblage | |

| Community/economic development funds | grants | City government initiatives | |

| Zoning | lower development burden | amendments, special uses, bonuses |

Abbreviations: HHS, Health and Human Services; CED, Community Economic Development; CDFI, Community Development Financial Institution; PA-FFFI, Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative; CA-FWF, California FreshWorks Fund; NMTC, New Markets Tax Credit; FFRI, Fresh Food Retailer Initiative.

Many state-level initiatives emulated the nation’s first program, PA-FFFI, which was established in 2004 with $30 million of funding from the Pennsylvania House Appropriations Committee (16). Following this initial investment, PA-FFFI leveraged nearly $150 million from other sources of capital to create a diverse fund of grants and low-interest loans to develop or preserve food retail in food deserts (17). Eligible projects for PA-FFFI had to be: “located in a low- to moderate-income census tract; provide a full selection of fresh foods; [and] locate in areas that are currently underserved” (18). While the program ended in 2010 after initial funds were deployed, key stakeholders from PA-FFFI - TFT and TRF - continued efforts to develop supermarkets in food deserts in Pennsylvania and beyond (19). Another state-level program, the California FreshWorks Fund (CA-FWF), assembled multiple sources of funds to tailor financing packages for specific projects. Announced in 2011, CA-FWF drew upon a broader range of investors, including regulated (conventional banks) and unregulated (mission-driven entities) lenders. This structure allowed CA-FWF to make grants and loans up to 90 percent of a project’s value; this compares to a more typical rate of 60 percent that renders many challenging urban sites undevelopable (20). Similar to PA-FFFI, CA-FWF stakeholders have positioned the fund as a means of economic development and improving healthy food access. Though the Fund listed the state as a partner, this support exists outside of the legislative process (21).

Partially modeled on PA-FFFI, the federal HFFI committed $400 million between three agencies: the Treasury Department, Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (22,23). Though originally enacted by President Obama in 2010, HFFI was formally passed by Congress as part of the Agricultural Act of 2014, and used existing mechanisms to steer resources toward programs that increase healthy food access.

Administered through the Treasury’s CDFI Fund, the New Market Tax Credit program encourages development in low-income areas by offering tax credits against the investor’s federal income tax. In Obama’s 2010 HFFI announcement, $250 million of the $400 million overall funding commitment was designated from NMTC allocations to CDFIs. In an effort to build capacity among CDFIs, the Fund also issued annual Financial Assistance (FA) awards up to $2 million (26). From 2011–2014, 46/538 FA awards were designated for HFFI-related efforts (HFFI-FA), and used for a variety of purposes, including loan fund capitalization or creating a loan loss reserve, so long as the amount was matched by non-federal funds (27).

Local municipalities also attracted supermarkets to underserved areas in a variety of ways including financing, in-kind support (land or technical assistance), and tax abatements. Special incentive zones may be drawn by local officials or through more formulaic designations such as USDA-defined food deserts. To fund initiatives requiring capital expenditures, cities may devote federal redevelopment dollars to increasing food access; for instance, Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), which many cities automatically receive based on a formula that considers poverty and population, among other indicators. For example, New Orleans used special post-Katrina CDBG funds to help seed their Fresh Food Retailer Initiative.

Rather than provide direct grant or loan support, the NYC Food Retail Expansion to Support Health Initiative (NYC-FRESH) effectively reduced the cost of development for eligible food retailers in designated parts of the city (28). This was achieved through zoning incentives, including added development rights, lowered parking requirements, and permitting larger stores in certain districts, as well as financial incentives, including exemptions or reductions of city taxes. Similar strategies to relax development regulations or taxes also existed in other cities, such as Washington, DC.

Summary of Fresh Food Financing Projects

Based on this methodology, 126 distinct projects were identified: 90 projects completed (the earliest in 2005), and 36 projects listed as planned or in development. Of the 126, valid store size (n=104), opening year (n=91), and employee counts (n=84) were obtained for the majority of projects. Seventeen stores opened between 2005–2010, though the majority opened following the implementation of HFFI (n=73 since 2011), as illustrated in Figure 1. Northeastern states had the most projects (n=43), followed by Southern (n=35), Midwestern (n=28) and Western states (n=20). More specifically, clusters of projects exist in Mid-Atlantic states and Southern California, largely overlapping with major state-level initiatives in those regions (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Fresh Food Financing Projects in the US, 2004–2015, by Project Characteristics and Region. The number of projects that included health features or were built on existing supermarket sites are also noted. Data source: Author’s database.

Figure 2.

Fresh Food Financing Projects in the United States, 2004–2014. Density overlay draws attention to major city-based clusters of projects in places such as New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Diego and Los Angeles. Data source: Author’s database.

Nearly 2.9 million square feet of supermarket space has been built or planned, with an average building area of just over 28,100 square feet (standard deviation = 22,056), and over 6,500 jobs have been created (excluding construction jobs), with an average of 78 jobs per project (standard deviation = 80). Forty-seven projects (37 percent of all projects) were developed on or in existing supermarket sites.

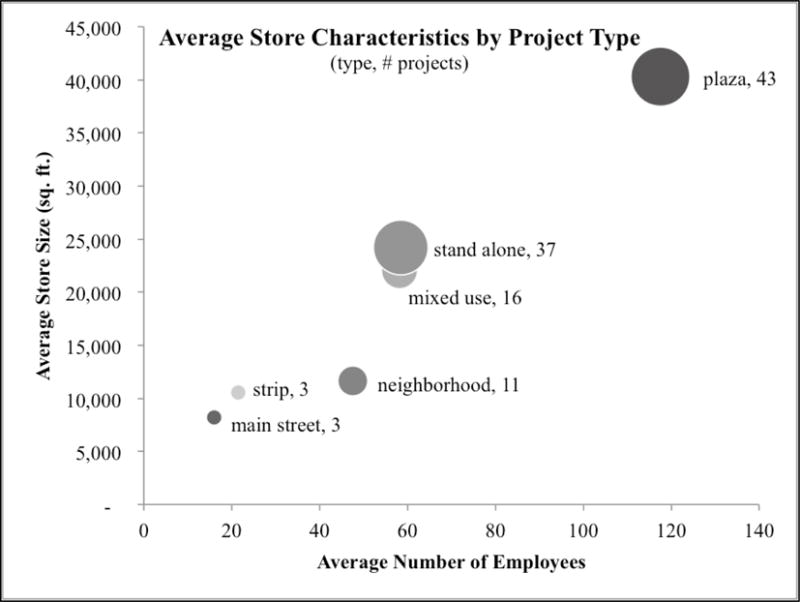

Most projects were classified as shopping plazas (n=43) and stand-alone stores (n=37), while mixed-use (n=16), neighborhood (n=11) and main street developments (n=3) were less prevalent (see Figure 3). The most common types of retail operators were regional chains (n=54), though local retailers (n=39) and large national chains (n=28) were relatively prevalent. In terms of business structure, cooperatives (n=6), and nonprofits (n=6), discount stores (n=25) were also represented. Health programming was noted in 30 projects, representing 24 percent of projects in this study.

Figure 3.

Average Characteristics of Fresh Food Financing Projects in the United States, 2004–2015. Plaza and stand-alone developments were the largest projects in terms of both store size and number of employees, and the most prevalent. Data source: Author’s database.

Local financing sources were the most prevalent (75 projects), while 73 projects used federal funding, most often in the form of NMTCs (30 projects). State funds were similarly common, with 33 projects using a state-level resource (see Table 3 for full summary of project and development characteristics by financing levels). On average, projects receiving local funding incentives or NMTC financing were significantly larger than those that did not, while projects with financing from the HHS-CED grants or HFFI-FA were significantly smaller than those without these types of funding (see Figure 4).

Table 3.

Project Characteristics and Levels of Financing for New Supermarket Development in US Food Deserts, 2004–2015.

| Financing Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal | State | Local | |

| Project Characteristics | % w/in Project Characteristics (% w/in Financing Level) | ||

| Retailer Characteristics | |||

| National | 54 (21) | 7 (6) | 61 (23) |

| Regional | 52 (38) | 33 (55) | 76 (55) |

| Local | 72 (38) | 33 (39) | 36 (19) |

| Cooperative | 83 (7) | 0 (0) | 33 (3) |

| Nonprofit | 33 (3) | 17 (3) | 33 (3) |

| Discount Retailer | 64 (22) | 8 (6) | 60 (20) |

| Health Program | 83 (34) | 40 (36) | 60 (24) |

| Development Characteristics | |||

| Strip | 100 (4) | 33 (3) | 33 (1) |

| Neighborhood | 55 (8) | 18 (6) | 45 (7) |

| Mixed Use | 56 (12) | 13 (6) | 88 (19) |

| Main Street | 33 (1) | 33 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Plaza | 63 (37) | 37 (48) | 56 (32) |

| Stand Alone | 49 (25) | 30 (33) | 70 (35) |

| Old Site | 67 (42) | 39 (55) | 46 (28) |

|

| |||

| Total | 58 (100) | 26 (100) | 60 (100) |

Figure 4.

Differences in Average Size of Fresh Food Financing Projects by Funding Source, 2004–2015. Bars represent the average size of store receiving a type of financing, and p-values are noted above for differences in size between projects receiving and not receiving the financing type. The dashed line represents average store size for all projects in the study. Data source: Author’s database.

DISCUSSION

Themes of Financing and Development

Based on the types of stores and incentive packages used by fresh food financing projects, several themes are evident. First, plaza and stand-alone types of developments were most prevalent in this study, and also were the most common recipients of federal and local assistance. This may indicate something of the size and scope of these types of projects, as well as their capital requirements. For example, NMTC-financed projects were significantly larger than those without that type of funding. Notable for urban food deserts and redevelopment efforts, plaza and stand-alone projects require sites that allow low-density development and are not as easily embedded within a traditional street grid.

Beyond raw numbers of financing levels, general themes of financing mechanisms were also evident and are useful ways to consider how funds motivate different types of projects. Though these categories are neither mutually exclusive nor all-encompassing, three models of financing and development are offered as major trends in fresh food financing. First, a professionalized model tends to follow processes espoused by TFT and TRF, typically including stakeholder involvement, a regional or independent operator, and an assemblage of flexible financing tools (29). Projects often use dedicated funding sources, federal (i.e. HFFI), state (i.e. CA-FWF, PA-FFFI), or local (i.e. NYC-FRESH) to provide financing packages tailored to project needs.

The flexible financing made available by HFFI may have helped release a pipeline of food access projects that had built up as public interest in food deserts rose leading up to 2011. Additionally, the maturity of the fresh food financing industry, embodied by the professionalized model of development, combined with familiar federal tools of community and economic development is also likely to have contributed to the surge in projects over the last five years.

Second, a streamlining/fast-tracking model aims to lessen the burden associated with building or expanding a supermarket, and is largely overseen by local authorities. The model centers on the relationship between the development project and local government, who must identify eligible projects or areas to receive incentives, and may also result from championing by local leaders. For example, the NYC-FRESH program identifies eligible areas through an interactive website, and also details the minimum eligibility standards in terms of the amount and variety of food sold. Zoning and financial incentives range from allowing different uses by-right to easing density standards and reconfiguring streets to allow for supply vehicles to access loading zones.

Finally, a start-up model describes instances when area institutions or organizations pursue new retail development and typically fundraise beyond the development channels used by the first two financing models. To cover costs, some retailers in this model operate alternative business practices to conventional retailers, including cooperatives and nonprofits, or adopt a much smaller retail footprint. Nevertheless, some start-up projects still receive traditional community development funding, such as HHS-CED or HFFI-FI, both of which supported significantly smaller than average projects.

Themes of Health Promotion

Health promotion goals are often framed as supplemental and post-development aspirations for projects and few, if any, projects are held to health expectations at the outset. Nonetheless, some supermarkets include explicit efforts to improve health. Projects with health features included national, regional, and local retailers, nonprofits and deep discounters, and over 80 percent of those projects in this study received some type of federal support. Overall, 24 percent of projects in this study included health features, though these efforts varied widely. I characterize general themes of these health-oriented activities below.

Some retailers oriented their business plan to include health in ways that may require a form of subsidy or outside support. For example, Fare & Square (Chester, PA) operates under a mission-driven, nonprofit model that allows a greater focus on health and away from marketing of less-healthy options. While the store offers an assortment of healthy and unhealthy items, it has also made efforts to promote healthier options and provide a robust produce department. An emerging business strategy of providing in-store healthcare has been led by Brown’s ShopRite Stores, a regional operator in the Philadelphia area, which leases supermarket space to a Federally Qualified Health Clinic. This is particularly notable in an industry where square footage equates to retail sales, and because it requires early commitment in the development process.

Other retailers have included health features by obtaining outside support (technical and financial) to implement programs, beyond the financing required to simply develop and open the store. For example, while most Save-a-Lot developments do not include health-focused programming, several stores in Kansas City, St. Louis, and Chicago have partnered with local health-focused stakeholders, including medical centers, community development organizations, or social service providers. In Philadelphia, The Fresh Grocer, a repeat beneficiary of PA-FFFI, has allowed researchers to conduct randomized in-store promotion and placement interventions for healthier items (30).

Most broadly, the grocery industry has responded to growing consumer health awareness by using a variety of wellness programming to attract and retain customers. Retailers may view health and wellness as part of their brand, or they may incorporate health-promoting practices without the knowledge of customers. These efforts range from basic marketing efforts of natural and organic products, to hiring of store dietitians and wellness coordinators and implementation of cooking classes and wellness rewards programs. Evaluation of many of these efforts is notably limited.

Conclusion

Because little comparative knowledge exists outside professional circles, new policies and programs to incentivize supermarket development cannot be fully informed by the history and progress made in this arena. I employed a broad approach to describe different methods to fund and develop new stores, as well as the different types of development outcomes.

My findings highlight the importance of retailer initiative in health promotion beyond offering healthy options, including internally-managed programs and partnerships with outside entities. As 80 percent of projects with health features received some type of federal financing, it is also worth considering how this level of monetary support either motivates or enables retailers to include health-promoting efforts or programs. Furthermore, in scenarios where retailers are pursued as partners, in-store health promotion requirements are often cited as overly prescriptive; thus, the current policy environment cedes the choice of whether or not to participate in health promotion to the supermarket operator.

This study has several limitations. The constructed dataset incorporates a range of secondary data; while pragmatic, this approach introduces potential error based on the reliability of sources, and will not reflect undocumented projects. Additionally, it is likely that projects and programs were unintentionally omitted from the study. However, the search methodology was intended to capture a sufficiently large group of projects as to draw reasonable conclusions about the field as a whole. Indeed, practitioners can improve on the method of database development by providing their own proprietary information to future researchers.

Though nominally united under the banner of fresh food financing, projects are conceived of, planned, and executed for a diverse set of reasons and through an equally diverse set of pathways. As researchers seek to understand and compare how new stores might affect public health outcomes, and as planners and advocates seek to initiate new projects, it is important to contextualize existing projects within this diversity. Given recent suggestions that new supermarkets alone are insufficient for health behavior change, greater attention to these nuances is needed from program designers, policymakers, and advocates who seek to continue fresh food financing programs (12,13).

Acknowledgments

During the study and manuscript preparation, I was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and NIH/NHLBI Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Cardiovascular Disease Prevention (Grant #T32-HL007034). I am grateful for the input of Amy Hillier, PhD, Allison Karpyn, PhD, Eugenie Birch, PhD, and Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, on several iterations of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Federal Reserve System.

I declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Andreyeva T, Blumenthal DM, Schwartz MB, Long MW, Brownell KD. Availability and prices of foods across stores and neighborhoods: the case of New Haven, Connecticut. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2008 Oct;27(5):1381–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Jan;36(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morland K, Diez Roux AV, Wing S. Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Apr;30(4):333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inagami S, Cohen DA, Finch BK, Asch SM. You are where you shop: grocery store locations, weight, and neighborhoods. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Jul;31(1):10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giang T, Karpyn A, Laurison HB, Hillier A, Perry RD. Closing the Grocery Gap in Underserved Communities: The Creation of the Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008 May;14(3):272–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PHH.0000316486.57512.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pennsylvania House Appropriations Committee. Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative [Internet] 2010 Mar; [cited 2015 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.ncsl.org/documents/labor/workingfamilies/PA_FFFI.pdf.

- 7.Goldstein I, Loethen L, Kako E, Califano C. Policy Publication, The Reinvestment Fund [Internet] Philadelphia, PA: The Reinvestment Fund; 2008. Aug, CDFI Financing of Supermarkets in Underserved Communities: A Case Study. [cited 2015 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.trfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/06/Supermarkets_Full_Study.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Reinvestment Fund. The Economic Impacts of Supermarkets on their Surrounding Communities [Internet] :2006. [cited 2015 Dec 20]. Report No.: Issue 4. Available from: http://www.trfund.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/supermarkets.pdf.

- 9.TRF Commercial Real Estate Group. Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative [Internet] 2008 [cited 2105 Dec 20]. Available from: http://planningpa.org/presentations08/fresh_food_financing.pdf.

- 10.Cummins S, Findlay A, Higgins C, Petticrew M, Sparks L, Thomson H. Reducing Inequalities in Health and Diet: Findings from a Study on the Impact of a Food Retail Development. Environ Plan A. 2008 Feb;40(2):1. 402–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang MC, MacLeod KE, Steadman C, Williams L, Bowie SL, Herd D, et al. Is the Opening of a Neighborhood Full-Service Grocery Store Followed by a Change in the Food Behavior of Residents? J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2007 Dec;2(1):30. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elbel B, Moran A, Dixon LB, Kiszko K, Cantor J, Abrams C, et al. Assessment of a government-subsidized supermarket in a high-need area on household food availability and children’s dietary intakes. Public Health Nutr. 2015 Oct;18(15):2881–90. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummins S, Flint E, Matthews SA. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014 Feb;33(2):283–91. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller D, Engler-Stringer R, Muhajarine N. Examining food purchasing patterns from sales data at a full-service grocery store intervention in a former food desert. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:164–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubowitz T, Ghosh-Dastidar M, Cohen DA, Beckman R, Steiner ED, Hunter GP, et al. Diet And Perceptions Change With Supermarket Introduction In A Food Desert, But Not Because Of Supermarket Use. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015 Nov;34(11):1. 1858–68. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans D, Weidman J. Growing Network: Fresh Food Financing Initiative [Internet] Governing. 2011 [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.governing.com/blogs/bfc/Fresh-Food-Financing-Initiative-070711.html.

- 17.Smith P. The Reinvestment Fund: A Healthy-Food Financing Leader [Internet] Community Developments Investments. 2012 [cited 2016 Feb 29 ]. Available from: http://www.occ.gov/publications/publications-by-type/other-publications-reports/cdi-newsletter/august-2012/healthy-foods-ezine-article-2-reinvestment-fund.html.

- 18.The Reinvestment Fund. Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative: Providing Healthy Food Choices to Pennsylvania’s Communities [Internet] 2008 [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://planningpa.org/presentations08/fresh_food_financing.pdf.

- 19.The Reinvestment Fund. Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative [Internet] Financing and Development, The Reinvestment Fund; [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.trfund.com/pennsylvania-fresh-food-financing-initiative/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sporte S, Howard C. The California FreshWorks Fund: Bringing Food to the Community [Internet] Community Developments Investments. 2012 [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.occ.gov/publications/publications-by-type/other-publications-reports/cdi-newsletter/august-2012/healthy-foods-ezine-article-4-ncbci.html.

- 21.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. State Initiatives Supporting Healthier Food Retail: An Overview of the National Landscape [Internet] US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/Healthier_Food_Retail.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pennsylvania House of Representatives. Evans: Idea for Farm Bill’s Healthy Food Financing Initiative born in Pa [Internet] PA House of Representatives News Release; 2014. [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.pahouse.com/Evans/InTheNews/NewsRelease/?id=35983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treasury Public Affairs, USDA Office of Communications, HHS/ACF Press Office. Obama Administration Details Healthy Food Financing Initiative [Internet] 2010 [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://wayback.archive-it.org/3926/20131018160911/http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2010pres/02/20100219a.html.

- 24.Office of Community Services. CED Abstracts: CED HFFI Grantees FY 2011 [Internet] Office of the Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ocs/resource/2011-ced-hffi-grantees. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Office of Community Services. CED Grant Awards FY 2012 [Internet] Office of the Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. Available from: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ocs/resource/fy-2012-ced-grantees#car. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Community Development Financial Institutions Fund. Community Development Financial Institutions Program [Internet] US Department of the Treasury; 2015. [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.cdfifund.gov/what_we_do/programs_id.asp?programID=7. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Community Development Financial Institutions Fund. Searchable Award Database [Internet] US Department of the Treasury; 2014. [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.cdfifund.gov/awardees/db/index.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 28.City of New York. Food Retail Expansion to Support Health [Internet] 2013 NYC.gov. [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/misc/html/2009/fresh.shtml.

- 29.Harries C, Koprak J, Young C, Weiss S, Parker KM, Karpyn A. Moving From Policy to Implementation: A Methodology and Lessons Learned to Determine Eligibility for Healthy Food Financing Projects. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014 Sep;20(5):498–505. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster GD, Karpyn A, Wojtanowski AC, Davis E, Weiss S, Brensinger C, et al. Placement and promotion strategies to increase sales of healthier products in supermarkets in low-income, ethnically diverse neighborhoods: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Jun 1;99(6):1359–68. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.075572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]