Abstract

Objective:

Callous-unemotional (CU) traits increase risk for children developing severe childhood aggression and Conduct Disorder. CU traits are typically described as highly heritable and debate continues about whether the parenting environment matters in their etiology. Strong genetically-informed designs are needed to test for the presence of environmental links between parenting practices and CU traits. Our objective was to determine whether parental harshness and parental warmth were related to children’s aggression or CU traits when accounting for genetically-mediated effects.

Method:

We examined 227 monozygotic twin pairs (454 children) drawn from population-based and at-risk samples of twin families, leading to oversampling of twins living in poverty. We computed multi-informant difference scores combining mother and father reports of their harshness and warmth towards each twin, and differences in mother reports of each twin’s aggression and CU traits.

Results:

Twin differences in parental harshness were related to differences in both aggression and CU traits, such that the twin who received harsher parenting had higher aggression and more CU traits. Differences in parental warmth were uniquely related to differences in CU traits, such that the twin receiving warmer parenting evidenced lower CU traits. These effects were not moderated by child sex, age, or family income, with the exception that the relationship between differential parental harshness and differential child aggression was stronger among low-income families.

Conclusion:

Parenting is related to child CU traits and aggression, over and above genetically- mediated effects, with low parental warmth being a unique environmental correlate of CU traits.

Keywords: aggression, callous-unemotional, heritability, monozygotic twins, parenting

INTRODUCTION

Childhood aggression is costly and harmful to families and communities, and increases risk for psychiatric disorders, particularly Conduct Disorder (CD) and Antisocial Personality Disorder, across the lifespan.1,2 Callous-unemotional (CU) traits are defined by deficient empathy and poor moral regulation, robustly predicting childhood aggression.3,4 CU traits were added to the DSM-5 as a specifier for the diagnosis of CD5, emphasizing the importance of understanding the etiology of CU traits. Research on child aggression has established that, despite prominent genetic influences6, harsh parenting can inadvertently socialize children to become aggressive and non-compliant,7–9 whereas parental positive reinforcement reduces child aggression.10,11 However, early studies focused on CU traits concluded that these traits developed independently of parenting,12,13 Subsequent twin studies largely supported this conclusion, suggesting that 40%—78% of the variance in CU traits is attributable to genetic influences.14

Nevertheless, research that identifies environmental factors related to CU traits can inform treatment efforts for CD and CU traits, even in the context of heritable risk. A systematic review found that parental harshness and low parental warmth were correlated with CU traits across childhood and adolescence.15 Recent studies suggest that parental harshness may be a general risk factor for aggression and CU traits, whereas low parental warmth may be a specific risk factor for CU traits.16–19 In particular, low parental warmth is thought to impair the development of emotional sensitivity and empathic concern, thus increasing risk for CU traits.4 However, a limitation of prior studies is use of non-genetically informed designs, making it hard to know whether associations reflect the actual influence of parenting on child outcomes, or whether they arise from unmeasured gene-environment correlations (rGE)20. Passive rGE reflects the fact that biological parents provide their child with both his/her genes and familial environment, potentially causing the two to correlate (e.g., parents low on warmth pass on genes of risk for CU traits, while also creating environments that further increase risk).21 Evocative rGE reflects situations in which the child elicits an environment consonant with his/her genes (e.g., a callous child frequently rejects parental warmth, causing his/her parents to eventually reduce their levels of warmth).21

A recent adoption study found that low warmth displayed by adoptive parents was related to child CU traits and disrupted the heritability of CU traits.22,23 Although adoption studies circumvent contributions from passive rGE confounds (since parents and child do not share genes), they do not fully address evocative rGE effects. Thus, studies are needed to address the fact that children may have inherited characteristics that elicit harsher or less warm parenting, as well as the fact that both CU traits and parenting are partially genetic in origin14,24. A monozygotic (MZ) differences design circumvents these genetic confounds because MZ twins share 100% of their genes, with each twin serving as the “genetic control” for the other.25 In this way, the MZ differences design allows us to specifically examine non-shared environmental influences on the association between parenting and CU traits, controlling for well-documented genetic influences on CU traits and parenting.14,24,26 One previous MZ twin differences study reported that parental harshness was cross-sectionally related to higher CU traits and child aggression at age 7.27 However, this study did not examine parental warmth, nor did it explore shared versus unique effects of parental harshness and warmth on CU traits versus aggression. Moreover, with the exception of a handful of birth cohort studies,28,29 few studies of parenting and CU traits have used representative samples, focusing instead on samples that are not generalizable, including adopted22,23 and clinic-referred16,30 children. Finally, no genetically- informed studies have tested whether these effects are confined to (or enhanced in) specific sub-populations (e.g., specific ages, gender, or income groups), a surprising gap in the literature given the widely recognized importance of these variables in developmental models of antisocial behavior more broadly.8

In the current study, we examined whether parental harshness and low warmth predicted child aggression and CU traits within a representative cohort of MZ twins that was oversampled from children living in poverty. We used an MZ twin differences design in which each twin acts as the other’s genetic “control”, to explore parenting effects free of genetic and passive and evocative rGE effects. Finally, we explored whether the differential effects of parenting on CU traits and aggression were moderated by child gender or age, and among low versus high-income families. Based on work in non-genetically informed observational designs,16–19 we hypothesized that parental harshness would be related to both aggression and CU traits, but low parental warmth would only be related to CU traits, and that these effects would be especially pronounced in males,8 younger children,31 and among low SES families20.

METHOD

Sample

We examined MZ twin families who participated in the Twin Study of Behavioral and Emotional Development in Children (TBED-C) within The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR).32 Recruitment procedures, response rates, and participation rates for the TBED-C are described extensively elsewhere.32 Briefly, data came from two “sister” cohorts. The first cohort was sampled via birth records to represent families with twins living within 120 miles of Michigan State University.32,33 The second cohort was sampled from the same region, but only from neighborhoods with moderate-to-high poverty.32,33 By combining the two cohorts, the resulting sample represents families living in south-central Michigan with an effective oversampling of families living in impoverished contexts, an ideal sample distribution for studying aggression and CU traits since poverty is a robust risk factor of these outcomes.8,20,34 Data were used from a subsample of 227 MZ twin pairs from the TBED-C that had mother reports for both twins for the CU traits measures (N=454 children). Zygosity was established by using a physical similarity questionnaires administered to primary caregivers.35,36 In the current sample, twins were 6–11 years old (M=7.80, SD=1.45) and 48.5% were female. Twins from the sample recruited from neighborhoods with moderate-to-high poverty were younger than twins from the representative sample (see Table S1, available online). Ethnic group memberships were endorsed at rates comparable to those of the State of Michigan (e.g., current sample: 81.1% Caucasian-non Latino and 6.2% African-American; local census: 85.5% Caucasian and 6.3% African-American)37. The remaining ethnic group memberships were: 1% Asian, 3% Latino/a, 1% Pacific Islander, and 6% not specified/other. Finally, a significant proportion families in the sample reported incomes under $25,000 (13%), which is notable because it crosses federal poverty thresholds, and is the same proportion seen in Michigan census data.37 Thus, recruitment methods for the TBED-C that combined a population-based sample and at-risk sample effectively produced a sample that was generalizable to the wider Michigan population with an effective oversampling of twins living in impoverished neighborhoods (see Table S1, available online).32,33

Procedures

Children provided verbal assent and parents provided written informed consent. We used questionnaire data collected concurrently from mostly biological mothers (99%) and fathers (95%), with other data coming from step-mothers (0.4%), grandmothers (0.4%), step-fathers (5%), and grandfathers (0.5%). Step-mothers and grandmothers were counted as “mother-report” and step-fathers and grandfathers as “father-report”. However, results were unchanged were these handful of cases were excluded from analyses. 186 (82%) twins lived in two-parent homes (i.e., both mother and father, mother and step-father, or mother and partner) and 41 (18%) of twins lived in homes with an alternative household composition, including mother-headed households when parents were divorced (Table S2, available online, presents a detailed breakdown of the alternative household compositions). Twins from the sample recruited from neighborhoods with moderate-to-high poverty were less likely than twins from the representative sample to live in two-parent homes (χ2 =3.48, df=1, p<.05). Study approval was obtained from the Michigan State Institutional Review Board. Participants provided consent (parents) and ascent (children) and were compensated for their time.

Measures

Parenting.

We assessed parenting using the 50-item Parental Environment Questionnaire (PEQ), with items rated on a four-point scale (1=definitely true; 4=definitely false).38 Parental harshness was assessed via the 12-item conflict scale, which taps parental feelings about parent- child hostility (e.g., “I often lose my temper with my child). Parental warmth was assessed using the 12-item involvement scale, which taps parental feelings about affection, closeness, and involvement in the parent-child relationship (e.g., “My child knows I love him/her”). We summed items to create measures of parental harshness (mothers, α=.85; fathers, α=.87; combined, α=.87) and parental warmth (mothers, α=.67; fathers, α=.77). Although the internal consistency for mother-reported warmth is below that which is typically considered acceptable, we ultimately assessed parental warmth using the mean of mother and father reports, thus increasing the overall reliability of the parental warmth construct (combined α=.73).

Child behavior.

We assessed aggression via mother reports on the 10-item physical aggression subscale of the Subtypes of Antisocial Behavior Questionnaire (STAB),39 which taps physically- and reactively-aggressive behaviors (e.g., “hits others when provoked) (α=.86). We assessed CU traits via mother reports on the 24-item Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICU),40 which assesses callousness (e.g., “unconcerned about feelings of others”), uncaring (“always tries best”), and unemotionality (“hides feelings”), with items rated on a four-point scale (0=not true; 3=definitely true). Consistent with prior studies, we dropped items 10 and 23,41 computing a total score across 22 items (α=.84).

Moderators.

We examined four potential demographic moderators of links between parenting on child outcomes: (1) child sex; (2) child age (ages 6–7=“younger” (55.1%) and 8– 11=“older” (44.9%); i.e., our grouping approach was based both on the mean age of 7.80 and the desire to create age subgroups with approximately equally-sized samples), and (3) family income (low<$45,000 and high≥$45,000, consistent with the median income of $45,267 for Midwestern households based on census data33,37).

Analytic Strategy

We examined interclass correlations among study variables to establish phenotypic relationships between parenting and child outcomes. Consistent with recommendations for MZ difference studies, we also computed intraclass correlations within twin pairs to establish that MZ twins differed on parenting and child outcomes, and compared the magnitude of the difference within twin pairs for boys versus girls and high versus low income families using Fisher’s r-to-z transformations. Next, we created multi-informant difference scores for harsh and warm parenting by subtracting Twin 2’s score from Twin 1’s score and computing a mean of mother and father difference scores (Twin 1 was the older twin). For aggression and CU traits, we created difference scores based on mother report, as only mother reports were only available for CU traits and we wanted to ensure comparability for aggression and CU traits (i.e., unconfounded by rater effects). The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits, used to assess CU traits, was added to the study later once some participants had already taken part. Thus, there were fewer mother reports available and we focused our analyses on all available data where mothers had completed the ICU during the visit or if they completed a mailed version of the ICU. We computed descriptive statistics and correlations among the difference score variables. We used structural equation modelling to examine relationships between differential parenting and differential child outcomes within a model that accounted for the covariance between parental harshness and warmth and the covariance between CU traits and aggression. Because prior work has argued that extreme differences in parenting should elicit larger differences in child behavior,42 we repeated analyses for twins most discordant for parental harshness, warmth, or both (n=108), based on cut-offs of one standard deviation above/below the mean difference scores for each measure. The discordant groups did not differ significantly based on the proportion of boys and girls (x2=2.90, p=.09) or for the high versus low income groups (x2 =.04, p=.85). Finally, to test whether associations were the same for boys versus girls, younger versus older children, and low versus high income families, we ran a series of multi-group models within the full, unselected sample. We compared the fit of models where differential parenting-to-differential child behavior pathways were systematically fixed versus freed across groups. We conducted analyses in Mplus vs. 7.243 using full information maximum likelihood estimation.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

We computed descriptive statistics for parenting variables and child outcomes, and compared levels based on sex and family income. Reports of parental harshness and warmth did not differ significantly for boys versus girls or low- versus high-income families (Table S3, available online). Mother reports of aggression were significantly higher among boys, but otherwise levels of CU traits and aggression did not differ by sex or family income (Table S4, available online).

Phenotypic and intra-twin associations

We found significant phenotypic correlations between parental harshness and child outcomes (aggression, r=.51, p<.001; CU traits, r=.26, p<.001) and between parental warmth and child outcomes (aggression, r=−.10, p<.05; CU traits, r=−.10, p<.05) (Table 1). Intraclass correlations between MZ twins (which index their degree of similarity) revealed that, although MZ twins were generally quite similar to one another in their CU traits and aggression, they also evidenced some differences: child aggression, r=.56; child CU traits, r=.54 (Table S5, available online). Not surprisingly, however, they received similar (although not identical) parental treatment: parental harshness, r=.85 (mother-reported) and r=.85 (father-reported); parental warmth, r=.77 (mother-reported) and r=.86 (father-reported). In general, there were no differences in the magnitude of correlations within twin pairs on any study measures based on sex or income, with the exception that mothers reported their harshness to be more similar between twins within high income families (Table S5, available online).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations for the Full Phenotypic Sample and Monozygotic (MZ) Twin Differences for Study Variables

| Phenotypic multi-informant scores (N=454, full phenotypic sample) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M (SD) | Range | Parental Harshness | Parental Warmth | Aggression | |

| Parental Harshness (MF) | 390 | 20.42 (4.52) | 12.00—33.00 | |||

| Parental Warmth (MF) | 389 | 41.77 (2.80) | 34.00—48.00 | − .32** | ||

| Child aggression (M) | 375 | 18.01 (5.01) | 10.00—42.00 | .51*** | −.10* | |

| Child CU traits (M) | 454 | 12.61 (7.70) | 0.00—43.00 | .26*** | −.10* | .38*** |

|

MZ twin difference scores (N=227, full MZ twin sample) | ||||||

| N | M (SD) | Range | Parental Harshness | Parental Warmth | Aggression | |

| Parental Harshness (MF) | 195 | 1.78 (1.71) | .00–10.50 | |||

| Parental Warmth (MF) | 194 | 1.12 (.93) | .00–5.00 | −.17* (−.18†) | ||

| Child aggression (M) | 187 | 3.03 (3.09) | .00–21.00 | .46*** (.53***) | −.03 (−.03) | |

| Child CU traits (M) | 227 | 5.02 (4.83) | .00–23.00 | .34*** (.41***) | −.20** (−.24*) | .32*** (.39**) |

Note: The top rows present descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for study variables across the phenotypic sample of MZ twins aged 6–11 years old. Multi-informant scores were computed for each twin as the mean of mother and father reports for measures of parental harshness and warmth. Only mother reports were available for CU traits, so we used mother reports for both CU traits and aggression to ensure comparability between outcomes unconfounded by rater effects. The bottom rows present descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for MZ multi-informant twin difference scores. To create MZ multi-informant twin difference scores at the dyad-level for parenting, we combined mother and father reports for individual twins then subtracted Twin 2’s score from Twin 1’s score. Note that means, SDs, and ranges represent statistics for absolute difference scores for interpretability but correlations are for signed actual difference scores. Correlations between study variables for MZ twin differences were confirmed among twins most discordant for parental harshness and warmth (n=108 shown in parentheses). CU = callous-unemotional; M = mother report; MF = combined mother and father report.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

MZ Differences

MZ differences in parental harshness were correlated with differences in warmth (r=−.17, p<.01), such that the twin receiving harsher treatment also received less warmth, relative to his/her co-twin. MZ differences in aggression were positively correlated with differences in CU traits (r=.32, p<.001), such that the twin showing more aggression also evidenced higher CU traits relative to his/her co-twin. Such findings emphasized the need to control for the overlap of these variables in models (Table 1). MZ differences in parental harshness were moderately-to- strongly correlated with differences in aggression (r=.46, p<.001) and differences in CU traits (r=.34, p<.001). MZ differences in experiences of parental warmth, however, were only correlated with differences in CU traits (r=−.20, p<.01). These correlations were confirmed among twin pairs highly discordant in their experience of parenting (Table 1).

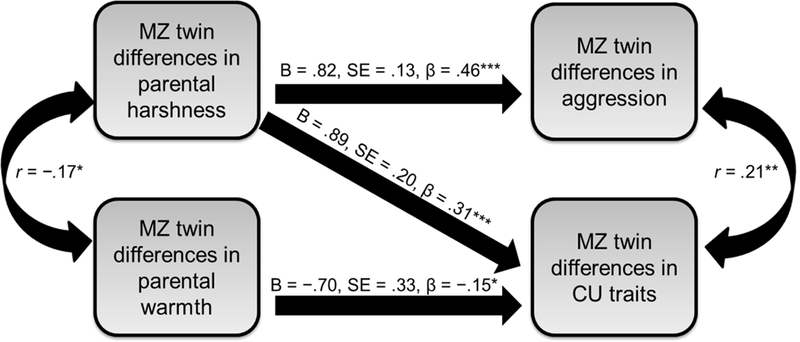

Next, while accounting for the overlap of parenting dimensions and child outcomes (Figure 1A), we found that differences in harshness predicted co-twin differences in aggression and CU traits (Figure 2A). Differences in parental warmth, by contrast, only predicted differences in CU traits (Figure 2B). These associations were confirmed among MZ twin pairs who were especially discordant in their parenting experiences (n=108; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

MZ Twin Differences Parental Harshness are Related to Monozygotic (MZ) Differences in Both Child Aggression and Callous-Unemotional (CU) Traits, but Differences in Parental Warmth are Only Related to Differences in CU Traits

Note: We examined associations in Mplus vs. 7.243 modeling pathways from MZ twin differences in parental harshness and warmth to MZ twin differences in aggression and CU traits in 227 MZ twin pairs aged 6–11 years old. To account for the overlap of parenting dimensions and child outcomes, we modeled correlations between MZ twin differences in parental harshness and warmth, and between MZ twin differences in aggression and CU traits. Figures show only the significant pathways. A. In the full sample, MZ twin differences in parental harshness were related to higher levels of child aggression and CU traits. That is, the twin who received more parental harshness also had higher aggression and CU traits. At the same time, MZ twin differences in parental warmth were uniquely related to CU traits. That is, the twin who received lower parental warmth had higher levels of CU traits. B. In the selected, subsample of twins (n=108) who were most discordant on measures of parenting, we confirmed significant associations between parenting and child outcomes. Note: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

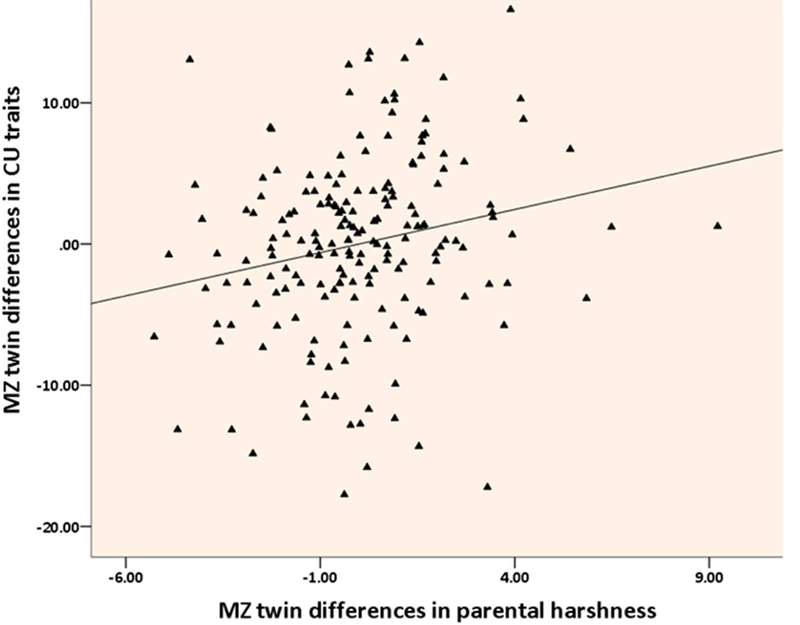

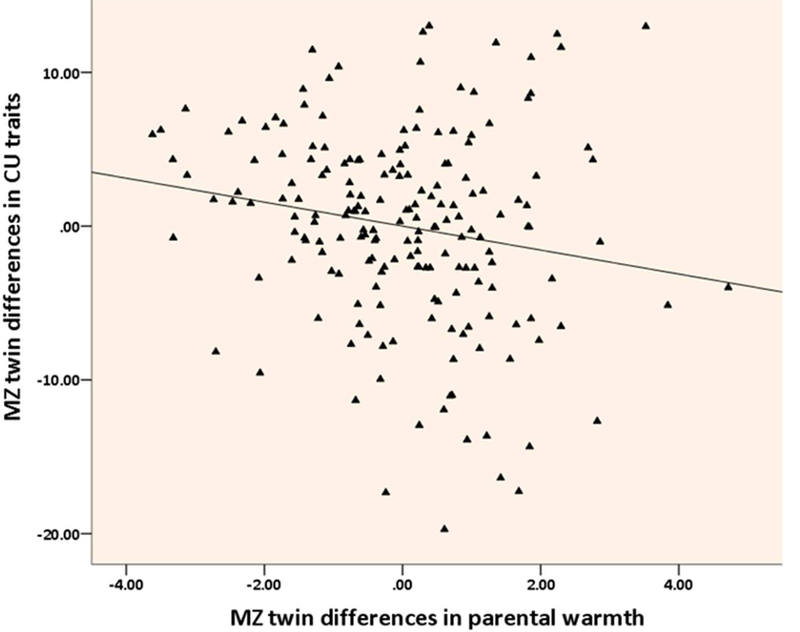

Figure 2.

The Twin Who Received More Parental Harshness and Lower Parental Warmth Had Higher Callous-Unemotional (CU) Traits, Accounting for The Overlap Of Parental Harshness And Warmth And Child Aggression. Note. MZ = monozygotic

Finally, multi-group analyses argued against moderation of the associations between differences in parenting and differences in CU traits by gender, age, or family income (Table S6, available online). Differences in parenting also predicted co-twin differences in aggression equally across boys and girls and the different age groupings. Interestingly, however, income moderated the effects of differences in parental harshness, but not parental warmth, on differences in child aggression (ΔΧ2=6.20, df=1, p=.01). Although the effects of MZ twin differences in parental harshness were significant for both groups, the magnitude of the non shared environmental effect of differences in parental harshness on twin differences in aggression was double that among twins from lower (B=1.29, SE=.23, p<.001) versus higher (B=.64, SE=.13, p<.001) income families.

DISCUSSION

The current study is the first to use a MZ twin differences design to establish that parental harshness is associated with both child aggression and CU traits, and lower parental warmth is uniquely related to child CU traits. Our findings are consistent with prior studies that have examined associations between parenting and CU traits within non-genetically informed designs (i.e., phenotypic associations in typical observational designs), including among clinic-referred children16,44 and community samples.17,34,45 Moreover, our findings add to an emerging body of research establishing the importance of parental harshness and low warmth to CU traits within genetically-informed designs, including large, population studies of twin pairs27,46 and among adopted children who are not related to their adoptive parents.20,22,23

Our findings have key implications for understanding prior literature. Studies have shown that heritability accounts for variability in both CU traits28,29,46 and parenting24. Despite the evidence for heritability however, the current results establish that parenting is associated with the development of CU traits via non-shared environmental pathways, a critical finding given the potential malleability of the parenting environment. This conclusion is bolstered by the strengths of our MZ twin differences design. Notably, the relationships between parenting and CU traits reflect pure non-shared environmental effects, controlling for passive and evocative rGE. The fact that these relationships persisted when we focused on extreme discordance for parenting experiences provides strong evidence for non-shared environmental associations between parenting and child CU traits, over and above genetic factors. Moreover, the non-significant moderation findings suggest that differences in harsh and warm parenting were similarly related to differences in CU traits among boys and girls, older and younger children, and children from lower and higher income families.

Of course, our findings are in the context of a cross-sectional design, and thus it could be that existing twin differences in CU traits evoked harsher and less warm parenting, as established in some non-genetically informed designs17,31. However, when our results are considered alongside recent findings from an adoption study22,23, which showed that heritable risk for CU traits emerged specifically in the context of adoptive parenting that was low on warmth, there is growing evidence to consider parenting as a non-heritable and “causal” factor in the development of CU traits. Thus, like the broader development of antisocial behavior7, parenting likely impacts the development of CU traits, while CU traits simultaneously undermine the parent-child relationship leading to harsher and less warm parenting, in a bidirectional cascade15,47.

It is also noteworthy that differences in parental harshness predicted twin differences in aggression. We found that the twin who experienced more parental harshness showed higher levels of aggression, even when taking into account the effects of harshness on overlapping CU traits and experiences of low parental warmth. This finding is consistent with prior reports that have linked MZ twin differences in parental harshness to children’s aggressive and externalizing psychopathology more broadly.42,48 In particular, corporal punishment and physical abuse have consistently been linked to risk for higher child aggression49 and CU traits15 via numerous potential mechanisms, including eliciting anger, pain, or fear from children, direct modeling of aggression, and reducing feelings of self-control in children49.

In relation to our second hypothesis, the environmental effect of parental harshness on child aggression was exacerbated among low-income families. One explanation for this moderation is that MZ twins from lower income families are more likely than MZ twins from higher income families to be (differentially) exposed to other risky environmental influences, including neighborhood danger or delinquent peers, which may increase discordance in their aggression or magnify emerging discordant harsh parenting effects.50 Thus, parenting cannot be considered in isolation from the context in which the parent-child relationship operates8,20,51 and treatments for CD and childhood aggression must take context into account.

The current study had significant strengths, including leveraging an MZ twin differences design in a relatively large, and well-sampled cohort with enrichment for those facing contextual risk, testing associations within a conservative structural equation model, and incorporating multi-informant measures of key study variables. Nevertheless, our findings should be considered alongside several limitations. First, although this was a representative sample, which increases the generalizability of findings, there may be important twin-singleton differences (e.g., unique obstetric factors), which could impact the conclusions drawn from twin studies and that have yet to be explored in relation to CU traits. There were also a high proportion of two-parent families (82%), meaning that findings may not generalize to samples comprised of a greater predominance of single-parent families. Second, based on mother-ratings of symptoms on the Child Behavior Checklist52, we found that 6% of twins included in our analyses were in the clinical range for number of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms and 8% for number of CD symptoms. These estimates are comparable with estimates reported in epidemiological studies of population cohorts of a similar age53–55 but lower than those in clinic-referred samples56. Further, while clinical cut-off scores have yet to be established for the ICU in children aged 6–11 years old, we only had one child in our sample with a score >41, which has been suggested as a cut-off for the ICU among a sample of older adolescents from community and juvenile justice settings57. Accordingly, our findings may not generalize to clinic-referred, adjudicated, or forensic samples of children. Third, measures of parenting were based solely on parent reports. However, using different approaches to assess parenting (e.g., alternative informants, observation, interview-rated) could introduce method variance error by artificially inflating twin differences. In this case, method variance is problematic because it could inadvertently magnify differences between twins, making it harder to conclude that findings stem from actual differences in parenting versus differences introduced by use of different assessment methods for each twin. However, note that in as a post-hoc test of the same models using twin reports of parenting (i.e., different informants), we found similar effects of differences in parental warmth on differences in CU traits. The twin who reported experiencing less parental warmth had higher parent- reported CU traits suggesting that the effects of low parental warmth exist across informants as well as within-informants, and support further the existence of this non-shared environmental pathway (Figure S1,available online). Nevertheless, future studies that control more explicitly for rater effects or parent perceptions could help to disentangle any unique associations between parenting practices and child CU traits.58 Fourth, although the MZ twin differences design is predicated on the assumption that MZ twins are genetically identical, studies have identified sources of differences between MZ twins, including epigenetic differences and somatic mosaicism (i.e., genetic differences arising from mutations that occur after conception)59, which could have influenced our findings. Finally, as noted above, associations between parenting and child outcomes were considered within a cross-sectional design. Future studies using follow-up data (currently being collected from the current sample) will provide the opportunity to examine prospective associations and the possibility that existing differences in child CU traits and aggression disrupt parenting practices over time by evoking less parental warmth or more harshness.17,31

Despite these limitations, the current study has important implications for our understanding of CU traits. The growing evidence base linking parenting to CU traits refutes the notion that CU traits are immutable or develop solely under heritable genetic influence. In particular, parental warmth is thought to increase the quality of the parent-child relationship and scaffolds emotional sensitivity, which enhances children’s ability to develop empathy lowering risk for CU traits.4,60 At the same time, parental harshness may increase risk for CU traits45 by increasing negative arousal and making it difficult for children to internalize rules and develop conscience.4,61 This evidence is critical for informing intervention efforts that are directed at parents to ameliorate CU traits or to reduce aggression and CU traits in children with CD. The limited evidence from randomized controlled trials in this area suggests that parenting interventions can be effective in reducing aggression even among children with high CU traits,62 and that intervention-related increases in parental warmth specifically reduce children’s CU traits.44 The findings from the current study highlight that adapted treatments for children with CD and/or CU traits could incorporate treatment modules targeting the emotional aspects of the parent-child relationships linked to low warmth, including increasing parent-child affiliation30 or training children to better recognize emotions to promote empathic concern.63

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01-MH081813 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and R01-HD066040 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Dr. Waller was supported by a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) T32 Fellowship in the Addiction Center, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan (2T32AA007477–24A1). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH, the NICHD, the NIAAA, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors thank all participating twins and their families for making this study possible.

Disclosure: Drs. Waller, Hyde, Klump, and Burt report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rebecca Waller, the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia..

Luke W. Hyde, the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor..

Kelly L. Klump, Michigan State University, Lansing..

S. Alexandra Burt, Michigan State University, Lansing..

REFERENCES

- 1.Scott S, Knapp M, Henderson J, Maughan B. Financial cost of social exclusion: follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. Bmj. 2001;323(7306):191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster EM, Jones DE, Group CPPR. The high costs of aggression: Public expenditures resulting from conduct disorder. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(10):1767–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, Kahn RE. Annual Research Review: A developmental psychopathology approach to understanding callous-unemotional traits in children and adolescents with serious conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55(6):532–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waller R, Hyde LW. Callous-Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood: The Development of Empathy and Prosociality Gone Awry. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2018;20:11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burt SA. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: A meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychological bulletin 2009;135(4):608–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson GR, Reid JB, Dishion TJ. Antisocial Boys. Eugene, Oregon: Castalia; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw DS, Gross HE. What we have learned about early childhood and the development of delinquency The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research: Springer; 2008:79–127. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke JD, Pardini DA, Loeber R. Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2008;36(5):679–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner F, Burton J, Klimes I. Randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in the voluntary sector for reducing child conduct problems: outcomes and mechanisms of change. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2006;47(11):1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waller R, Gardner F, Dishion T, et al. Early parental positive behavior support and childhood adjustment: Addressing enduring questions with new methods. Social Development. 2015;24(2):304–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oxford M, Cavell TA, Hughes JN. Callous/unemotional traits moderate the relation between ineffective parenting and child externalizing problems: A partial replication and extension. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(4):577–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wootton JM, Frick PJ, Shelton KK, Silverthorn P. Ineffective parenting and childhood conduct problems: The moderating role of callous-unemotional traits. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1997;65(2):301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viding E, McCrory EJ. Genetic and neurocognitive contributions to the development of psychopathy. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24(3):969–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW. What are the associations between parenting, callous- unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clinical Psychology Review 2013;33:593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasalich DS, Dadds MR, Hawes DJ, Brennan J. Do callous unemotional traits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems? An observational study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:1308–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waller R, Gardner F, Viding E, et al. Bidirectional associations between parental warmth, callous unemotional behavior, and behavior problems in high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:1275–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waller R, Gardner F, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN, Hyde LW. Callous-unemotional behavior and early-childhood onset of behavior problems: The role of parental harshness and warmth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(4):655–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills-Koonce WR, Willoughby MT, Garrett-Peters P, Wagner N, Vernon-Feagans L. The interplay among socioeconomic status, household chaos, and parenting in the prediction of child conduct problems and callous-unemotional behaviors. Development and psychopathology. 2016;28(3):757–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waller R, Shaw DS, Neiderhiser JM, et al. Towards an understanding of the role of the environment in the development of early callous behavior. Journal of Personality. 2017;85:90–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype → environment effects. Child development. 1983:424–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyde LW, Waller R, Trentacosta CJ, et al. Heritable and non-heritable pathways to early callous unemotional behavior American Journal of Psychiatry 2016;173:903–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waller R, Trentacosta C, Shaw DS, et al. Heritable temperament pathways to early callous-unemotional behavior. British Journal of Psychiatry 2016;209:475–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klahr AM, Burt SA. Elucidating the etiology of individual differences in parenting: A meta-analysis of behavioral genetic research. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(2):544–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Connor TG, Hetherington EM, Reiss D, Plomin R. A Twin-Sibling Study of Observed Parent-Adolescent Interactions. Child development. 1995;66(3):812–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plomin R, Caspi A, Pervin L, John O. Behavioral genetics and personality. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 1990;2:251–276. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viding E, Fontaine NM, Oliver BR, Plomin R. Negative parental discipline, conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits: monozygotic twin differences study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009; 195(5):414–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viding E, Blair RJR, Moffitt TE, Plomin R. Evidence for substantial genetic risk for psychopathy in 7-year-olds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(6):592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viding E, Jones AP, Paul JF, Moffitt TE, Plomin R. Heritability of antisocial behaviour at 9: do callous - unemotional traits matter? Developmental science. 2008;11(1):17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dadds MR, Allen JL, Oliver BR, et al. Love, eye contact and the developmental origins of empathy v. psychopathy. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2012;200:191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawes DJ, Dadds MR, Frost AD, Hasking PA. Do childhood callous-unemotional traits drive change in parenting practices? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2011;40(4):507–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burt SA, Klump KL. The Michigan state university twin registry (MSUTR): An update. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2013;16(1):344–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014 Current Population Reports. 2015. Accessed 09/11/2017.

- 34.Waller R, Shaw DS, Forbes EE, Hyde LW. Understanding Early Contextual and Parental Risk Factors for the Development of Limited Prosocial Emotions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43:1025–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peeters H, Van Gestel S, Vlietinck R, Derom C, Derom R. Validation of a telephone zygosity questionnaire in twins of known zygosity. Behavior genetics. 1998;28(3):159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burt SA, Klump KL, Gorman-Smith D, Neiderhiser JM. Neighborhood disadvantage alters the origins of children’s nonaggressive conduct problems. Clinical psychological science. 2016;4(3):511–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burt S, Klump K. Delinquent peer affiliation as an etiological moderator of childhood delinquency. Psychological Medicine 2013;43(6):1269–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elkins IJ, McGue M, Iacono WG. Genetic and environmental influences on parent-son relationships: Evidence for increasing genetic influence during adolescence. Developmental psychology. 1997;33(2):351–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burt SA, Donnellan MB. Development and validation of the Subtypes of Antisocial Behavior Questionnaire. Aggressive behavior. 2009;35(5):376–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frick PJ. The Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. https://sites01.lsu.edu/faculty/pfricklab/wp-content/uploads/sites/W0/2015/11/ICU-Parent.pdf 2004.

- 41.Waller R, Wright AG, Shaw DS, et al. Factor structure and construct validity of the parent-reported Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits among high-risk 9-year-olds. Assessment 2015;22(5):561–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Krueger RF. Differential parent-child relationships and adolescent externalizing symptoms: cross-lagged analyses within a monozygotic twin differences design. Developmental psychology. 2006;42(6):1289–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus User’s Guide. 1998–2016. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasalich DS, Witkiewitz K, McMahon RJ, Pinderhughes EE, Group CPPR. Indirect effects of the fast track intervention on conduct disorder symptoms and callous- unemotional traits: distinct pathways involving discipline and warmth. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2016;44(3):587–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waller R, Gardner F, Hyde LW, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Do harsh and positive parenting predict parent reports of deceitful callous behavior in early childhood? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53(9):946–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viding E, Frick PJ, Plomin R. Aetiology of the relationship between callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems in childhood. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190(49):s33–s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waller R, Hyde LW. Callous-Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood: Measurement, Meaning, and the Influence of Parenting. Child Development Perspectives. 2017;11(2):120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oliver BR. Unpacking externalising problems: negative parenting associations for conduct problems and irritability. British Journal of Psychiatry Open. 2015;1(1):42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gershoff ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological bulletin. 2002;128(4):539–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Asbury K, Dunn JF, Pike A, Plomin R. Nonshared environmental influences on individual differences in early behavioral development: A monozygotic twin differences study. Child development 2003;74(3):933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belsky J The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child development. 1984;55:83–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatrics in review. 2000;21(8):265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Prevalence, subtypes, and correlates of DSM-IV conduct disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological medicine 2006;36(5):699–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(7):703–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maughan B, Rowe R, Messer J, Goodman R, Meltzer H. Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: developmental epidemiology. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2004;45(3):609–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keenan K, Wakschlag LS. Are oppositional defiant and conduct disorder symptoms normative behaviors in preschoolers? A comparison of referred and nonreferred children. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):356–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Docherty M, Boxer P, Huesmann LR, O’Brien M, Bushman B. Assessing callous- unemotional traits in adolescents: Determining cutoff scores for the inventory of callous and unemotional traits. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;73(3):257–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waller R, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Wilson M, Hyde LW. Does early childhood callous-unemotional behavior uniquely predict behavior problems or callous-unemotional behavior in late childhood? Developmental Psychology. 2016;52:1805–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bruder CE, Piotrowski A, Gijsbers AA, et al. Phenotypically concordant and discordant monozygotic twins display different DNA copy-number-variation profiles. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;82(3):763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kochanska G Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: A context for the early development of conscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2002;11(6): 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kochanska G Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: from toddlerhood to age 5. Developmental psychology. 1997;33(2):228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elizur Y, Somech LY, Vinokur AD. Effects of parent training on callous-unemotional traits, effortful control, and conduct problems: Mediation by parenting. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2017;45(1):15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dadds MR, Cauchi AJ, Wimalaweera S, Hawes DJ, Brennan J. Outcomes, moderators, and mediators of empathic-emotion recognition training for complex conduct problems in childhood. Psychiatry research 2012;199(3):201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.