Abstract

We examined differences between children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and typical development (TD) over an 8-month period in: (a) longitudinal associations between expressive and receptive vocabulary, and (b) the extent to which caregiver utterances provided within an ‘optimal’ engagement state mediated the pathway from early expressive to later receptive vocabulary. Fifty-nine children (28–53 months at Time 1) comprised the ASD group, and 46 children (8–24 months at Time 1) comprised the TD group. Groups were matched on initial vocabulary sizes. Results showed the association between early expressive and later receptive vocabulary was moderated by group. A moderated-mediation effect was also found, indicating linguistic input provided within an optimal engagement state only mediated associations for the ASD group.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, vocabulary, early language, joint engagement, longitudinal data analysis, mediation analysis

Introduction

Young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) frequently exhibit substantial language delays, and nearly one third of children diagnosed with ASD remain minimally verbal at age five (Tager-Flusberg and Kasari, 2013). This is concerning because, in children with ASD, childhood language abilities predict important adult outcomes such as social functioning and independence (Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2012). An improved understanding of language development is of significant interest to researchers, so that the developmental and environmental factors that may positively influence language acquisition can be maximized within intervention contexts (e.g., Yoder et al., 2015). For children in the earliest stages of language development, vocabulary size is a developmentally appropriate focus of research.

Children’s vocabulary knowledge can be represented in two modalities. Expressive vocabulary size refers to the number of words children can say, while receptive vocabulary size refers to the number of words children can understand. In this study, we use the term cross modal to refer to the associations across expressive and receptive vocabulary modalities. Studying children who are just beginning to learn words can help clarify how the early emergence of vocabulary in one modality influences the other modality over time. Examining children with ASD in relation to their typically developing (TD) peers can illuminate developmental differences associated with ASD which, in turn, could aid intervention efforts that target these differences in this clinical population.

Cross modal, longitudinal correlations in vocabulary size

Prior theory posits that, in TD children, receptive language acts as a developmental catalyst for expressive language (Bornstein and Hendricks, 2010). Individual words are thought to be understood first, and later used appropriately. Understanding what words mean is a logical precondition for using most words functionally at a later time point. There is some empirical evidence to bolster assumptions about this causal pathway. For example, in the early stages of spoken language development, children’s receptive vocabulary typically emerges first and remains larger in size than expressive vocabulary (Benedict, 1979). Early receptive language is also a significant predictor of later expressive language in TD children (Bornstein and Hendricks, 2010; Watt et al., 2006).

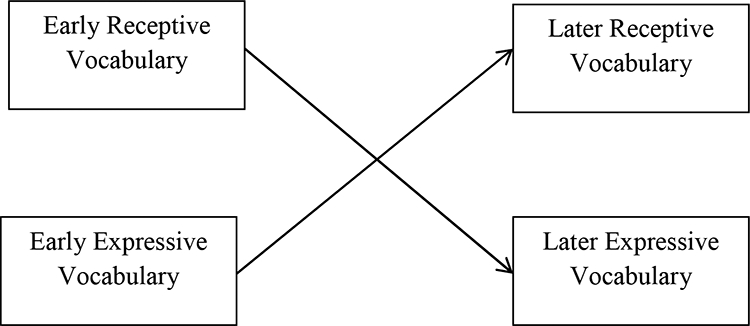

In contrast to this typical pathway, a recent study of preschool-age children with ASD showed that cross-modal correlations between early expressive and later receptive vocabulary were stronger than correlations between early receptive and later expressive vocabulary, even after controlling for concurrent cross-modal correlations and longitudinal within-modality correlations (Woynaroski, Yoder, and Watson, 2016). That is to say, there is correlational evidence that the primary direction of effect is from expressive vocabulary to receptive vocabulary in this group of children, rather than the reverse. This suggests that young children with ASD may show an “opposite” pattern in the strength of longitudinal, cross-modal associations than is expected for their TD peers, where the direction of effect is thought to be from receptive vocabulary to expressive vocabulary (see Figure 1 for an illustration). Woynaroski and colleagues suggest that the relative weakness of the early receptive to later expressive pathway may be because children with ASD are unable to process linguistic input to build their vocabularies unless it is provided during optimal caregiver-child engagement formats. However, we are not aware of any research that statistically compares the strength of longitudinal, cross-modal relations in children with ASD and TD children. Therefore, it is unclear the extent to which the pathway found in children with ASD is indeed atypical. Additionally, we do not yet have an explanation for differences in the strength of cross-modal associations that have been observed in children with ASD. This study is offered as an initial attempt to: a) corroborate assertions that there are group differences in the strength of cross-modal, longitudinal associations, and b) explore a potential mechanism for identified differences that can be tested further in future research.

Figure 1.

Longitudinal, cross-modal vocabulary associations.

Caregiver utterances and joint engagement

A potentially useful approach for understanding the relative strength cross-modal associations is to identify mediating variables, or variables that serve as intermediaries on the path from one language modality to the other (MacKinnon et al., 2007). A candidate mediator is caregiver linguistic utterances provided at times when the caregiver and child are engaged in such a way that is thought to be ‘optimal’ for language development (Bakeman and Adamson, 1984). Discerning caregiver utterances and joint engagement states that correlate with language learning has been of interest to developmental and ASD intervention researchers alike (Adamson et al., 2009; Siller et al., 2014). Recently, research has attempted to identify more precisely the types of caregiver language and engagement states that appear to promote vocabulary learning in children with ASD, which we outline below (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2014; McDuffie and Yoder, 2010).

The caregiver utterance type we focus on is follow in utterances, which occur when the caregiver provides a comment or suggestion regarding the child’s current focus of attention (see Table 1 for definition and examples). A significant amount of research has indicated that, in children with ASD, follow-in utterances lead to greater language learning than other types of caregiver talk, such as utterances that don’t follow the child’s attentional focus (McDuffie and Yoder, 2010; Parish-Morris et al., 2007; Siller and Sigman, 2002; 2008). Children with ASD often experience difficulty disengaging from a current focus of attention and shifting to a new focus of attention (Swettenham et al., 1998). This may inhibit the child from attending to and learning from interactional bids that are unrelated to their focus of attention. In turn, it may then be unlikely that the interaction will result in the child incorporating new vocabulary into their linguistic repertoire (either expressively or receptively).

Table 1.

Operational Definitions of Observational Codes

| Code | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Follow-in Utterance | The caregiver provides linguistic input following the child’s current focus of attention, either by describing what the child is looking at or playing with, or makes a suggestion about how the child could play with the toy. |

The child plays with a toy boat, and the caregiver says, “Look at the boat rocking in the water!” Or, the child plays with a baby doll, and the caregiver says, “Can the baby drink from the bottle?” |

| Higher-Order Supported Joint Engagement |

The caregiver and child are engaged with the same materials and the parent’s actions influence the child’s play, but the child does not visually reference the adult. The child reciprocates the adult’s play actions or collaborates with the adult in a play scheme. |

Turn taking sequences (e.g., taking turns placing puzzle pieces on a board), child imitating parent (e.g., caregiver makes a toy pig drink water, child makes a toy cow drink water), or the child following through on a verbal directive made by the caregiver |

| Lower-Order Supported Joint Engagement |

The caregiver and child are engaged with the same materials and the parent’s actions influence the child’s play, but the child does not visually reference the adult, nor does the child reciprocate the adult’s play actions or collaborate with the adult in the play scheme. |

The child and caregiver play with the toy farm house, each moving a toy around the house in such a way that the child must adapt his/her play to accommodate the parent’s actions. This accommodation is incidental to the parent’s presence, and does not reflect collaboration or turn taking. |

Joint engagement states are modes of dyadic interaction around objects or events that extend over a period of time. In their seminal research, Bakeman and Adamson (1984) showed that supported joint engagement, where the caregiver influences and scaffolds the child’s play with toys but the child does not explicitly acknowledge the caregiver’s involvement, is more influential on later language than coordinated joint engagement, where the child explicitly references the adult within the interaction. This relation holds for children with ASD as well as TD children (Adamson et al., 2009). In the early stages of development, explicit acknowledgement of the caregiver is usually shown through gaze shifts from the object to the adult or visa versa. This form of coordinated attention to object and person is particularly difficult for children with ASD (Mundy, Sigman, Ungerer & Sherman, 1986).

In more recent research (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2014), the supported joint engagement state has been further refined in order to parse the precise features of this state that are necessary for language learning. The joint engagement state we focus on is higher order supported joint engagement (HSJE). In this state, the caregiver’s play impacts the child’s play, and the child reciprocally or collaboratively responds to the caregiver’s interactive or play moves, but without explicitly acknowledging the caregiver by alternating gaze between the caregiver and the toys. In contrast, in lower order supported joint engagement (LSJE), the caregiver and child are engaged with the same objects in such a way that the caregiver’s play impacts the child’s physical interaction with the toys, but the child does not reciprocally respond to or collaborate with the caregiver (see Table 1 for definitions and examples)1. In HSJE, but not in LSJE, the caregiver and child are in a state where appreciation of the intentionality of the other is mutual, and both parties are aware of ‘doing something together’ (Tomasello, 1999). In neither state, however, is the child explicitly acknowledging the adult with gaze.

In traditional measures of supported joint engagement, HSJE and LSJE sub-states are not separated out. However, a recent study found that follow-in utterances provided within HSJE (HSJE + FI) predicted later receptive language, while follow-in utterances provided within LSJE or when the child was otherwise engaged with objects did not (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2014). This research underscores the need to examine not only the amount of follow-in utterances but also the joint engagement states that enable children with ASD to learn from linguistic input. HSJE + FI may be optimal for language learning because it represents a balance between two aspects of engagement: (a) it allows the child to simultaneously focus on the object labels and their referents, without also using cognitive resources to manage the interaction with the caregiver through gaze (Adamson et al., 2009; Bottema-Beutel et al., 2014), and (b) the social involvement with the caregiver that is indexed by child reciprocity within HSJE may increase the probability that the input is processed and is socially meaningful to the child (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2014). In LSJE, although the caregiver is influencing the child’s play with objects, there is no readily apparent social involvement from the child. The lack of social engagement during the provision of follow-in utterances may reduce the child’s attention or processing of the input and thus hamper the child’s ability to learn the meaning of any new words they hear during LSJE.

It is possible that HSJE + FI mediates cross-modal, longitudinal vocabulary relations, and that it does so to a greater extent for children with ASD than TD children (see Figure 2 for a visual depiction of the hypothesized mediation effect). The rationale for this prediction is most apparent for the early expressive to later receptive direction. When children are beginning to build expressive vocabularies, their word use may be a strong recruiter of caregiver scaffolding around play. When children talk about what they are playing with, caregivers may perceive this as an opportunity to shape the play as a joint interaction. Further, expressive vocabulary may be employed interactionally to reciprocate caregiver actions around toys in increasingly abstract and flexible ways, enabling the development of more frequent and longer bouts of HSJE (Adamson et al., 2009; Adamson & Bakeman, 2006).

Figure 2.

Hypothesized indirect effect of early expressive vocabulary size on later receptive vocabulary size, through HSJE + FI, with group moderating the b path. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; HSJE + FI = Higher-order supported joint engagement with caregiver follow-in utterances, TD = typically developing.

Although the effects of expressive vocabulary on HSJE + FI may be similar for children with ASD and TD, the effects of HSJE + FI on later receptive vocabulary may differ between these two groups. Children with ASD may be dependent on highly specific engagement formats in order to learn what words mean, while typically developing children may process caregiver linguistic input in a variety of formats. Further, TD children may experience HSJE + FI in greater amounts than is required for them to learn the meaning of new words, which would weaken the association between HSJE + FI and later receptive vocabulary for this group. A recent meta-analysis supports this view, showing that joint attention (a broad construct that includes HSJE) is more highly correlated with language in children with ASD as compared to TD children (Bottema-Beutel, 2016). Finally, other research has shown that children with ASD are more dependent than TD children on talk that is consistent with their focus of attention in order to correctly map words to their referents (Baron-Cohen, Baldwin, & Crowson, 1997).

The current study

The specific research questions examined in this study are as follows:

Are associations between early receptive and later expressive vocabulary sizes positive and conditional on group membership, with a stronger association in the TD group?

Are associations between early expressive and later receptive vocabulary sizes positive and conditional on group membership, with a stronger association in the ASD group?

Does HSJE + FI mediate the positive association between early expressive and later receptive vocabulary size, and to a greater extent in the ASD group?

Method

Study design

To address our research questions, we used longitudinal-correlational and intact-group comparison design elements. Expressive vocabulary size, receptive vocabulary size, and the number of intervals in which caregivers provided follow-in utterances during higher-order supported joint engagement were assessed at study entry. Expressive and receptive vocabulary sizes were assessed again 8 months later (+/− 2 weeks). TD and ASD children were group-wise matched on expressive and receptive vocabulary size at study entry.

Participants

Parental consent was obtained from all participants included in this study. Participants with ASD (n = 59; 48 male) are a subset from a larger study of useful speech development in children with ASD who were initially in the pre-verbal stage of language development (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2014; Woynaroski, Yoder, & Watson, 2016; Woynaroski et al., 2016; Yoder et al., 2015). At Time 1 for the present study, these children were between 28 and 53 months chronological age and had a clinical diagnosis of autism or PDD/NOS. If children had an existing diagnosis of autism or PDD/NOS through licensed and experienced community providers, their diagnoses were confirmed using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000), as administered by research staff who were research reliable on this instrument. Children who did not enter the study with a previous diagnosis were assessed and diagnosed by a licensed clinical psychologist who was research reliable on the ADOS and experienced with evaluating young children with ASD. Research diagnoses were based on best clinical judgment that the data from the ADOS and the clinical interview indicated that the child met criteria for autism or PDD/NOS according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition-Text Revision (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Children with co-morbid conditions such as severe sensory or motor impairments, established metabolic or neurological disorders, or genetic syndromes were excluded from the study. To prevent floor effects, children from the larger study with a score of zero at Time 1 for either expressive or receptive vocabulary were excluded.

The TD group included 46 children (24 male) who were between 8 and 24 months chronological age at Time 1. Children in the TD group were screened for prior evidence (i.e., professional diagnosis) or suspicion of developmental disabilities (i.e., referral for early intervention services or older sibling with a developmental disability) per parent report. They were also screened out if they received a score of zero on either expressive or receptive vocabulary measures. These TD controls were recruited for the current study and were group-wise matched to the ASD group on expressive and receptive vocabulary at Time 1. Following guidance in Mervis and Klein-Tasman (2004), we used a threshold p-value of 0.50 in t-tests of means to indicate that groups were sufficiently matched on these two variables of interest at Time 1. Our groups met this criteria for expressive vocabulary (p = 0.72), but not receptive vocabulary, where the ASD group mean was slightly higher. Therefore, in the analyses in which early receptive vocabulary was not controlled for, we dropped the participants in the ASD group with the 3 highest receptive vocabulary scores, which resulted in groups sufficiently matched on this variable (p = 0.51).

The groups were also approximately matched on mental age. However, the mental age assessment for the ASD group took place 4 months prior to the Time 1 vocabulary size and engagement state measures (i.e., at entry to the larger study of useful speech development), while the mental age assessment for the TD group was taken during the same visit as the Time 1 vocabulary size and engagement state measures relevant to the present study. To correct for this discrepancy in timing of the mental age assessment, we calculated a ‘corrected MA’ for the ASD group. We derived this correction by dividing the mental age equivalent by chronological age to get an approximate index of mental age growth per month, multiplying the result by 4, and then adding the product to the child’s mental age. Groups did not differ on this approximate mental age assessment (p = 0.67). See Table 2 for a summary of group means and standard deviations for early and late variables.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Group Differences for Continuous Study Variables by Group

| TD (n = 46) | ASD (n = 59) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Range | Mean | SD | Range | |

| ADOS Module 1 Social Communication Total | - | - | - | 22.24 | 4.29 | 6–28 |

| Mental Age at Study Entry† | 14.21 | 3.67 | 4.19–28.64 | 14.61 | 5.23 | 4.19–28.64 |

| Early Chronological Age*** | 14.72 | 3.94 | 28.73–24.13 | 39.36 | 6.81 | 28.73–52.57 |

| Early Receptive Vocabulary†† | 100.73 | 71.76 | 11–258 | 112.80 | 94.45 | 2–389 |

| Early Expressive Vocabulary | 28.70 | 37.99 | 1–170 | 26.22 | 32.78 | 1–181 |

| Early HSJE + FI††† | 6.76 | 10.33 | 0–41 | 3.93 | 6.20 | 0–46 |

| Later Receptive Vocabulary*** | 318.04 | 63.08 | 118–395 | 169.34 | 106.75 | 6–396 |

| Later Expressive Vocabulary*** | 212.04 | 110.00 | 7–384 | 78.7 | 91.60 | 0–396 |

Note. Vocabulary was assessed using the MacArthur Bates Communicative Development Inventories: Words and Gestures checklist. Mental age was assessed using the Mullen Scales of Early Learning. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; HSJE + FI = higher-order supported joint engagement with caregiver follow-in utterances; TD = typically developing. HSJE + FI was measured as the number of 5-second intervals out of 180 possible intervals.

Corrected mental age for the ASD group to account for the 4-month lag between study entry and Time 1 measures. Uncorrected mental age mean = 13.23 (4.79).

n = 56 for the ASD group (3 participants were dropped to better match groups on this variable)

Indicates group difference is significant at p < .001.

p = 0.08.

Measures

Mental age.

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; Mullen, 1995) was administered at study intake by trained research staff (as indicated above, study intake was 4 months prior to Time 1 measures for ASD group, and concurrent with Time 1 measures for the TD group). The MSEL is a standardized assessment normed for children from birth to 68 months. Mental age was calculated by averaging the age equivalency scores from visual reception, fine motor, receptive language, and expressive language subscales.

Vocabulary size.

The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (MCDI; Fenson et al., 2003), Words and Gestures version was administered at Time 1 and again 8 months later at Time 2. The MCDI is a caregiver-completed checklist of words that young children are likely to understand and/or say. Receptive vocabulary was derived by summing the raw totals for ‘words understands’ and ‘words says and understands’ columns. Expressive vocabulary was the raw total for the ‘words says and understands’ column only. Vocabulary size is an appropriate measure of language for our samples, as children were in the “preverbal” or “first words” stages of language learning at study entry (Tager-Flusberg et al., 2009). Our data did not suggest that ceiling effects were an issue, as only 1 participant achieved maximum scores on expressive and receptive vocabulary at Time 2.

Higher order supported joint engagement with caregiver follow in utterances (HSJE + FI).

HSJE and follow-in utterances were coded within a 15-minute caregiver-child free play session, conducted with a standard set of toys at Time 1 (toys included items such as blocks, a toy barn and animals, a baby doll and a bottle, etc.) Refer back to Table 1 for operational definitions of HSJE and FI. After a brief warm-up period, caregivers were asked to play with their child as they normally would at home. The session was video recorded, and videos were coded in three passes using ProCoder DV software (Tapp, 2003). In the first pass, coders identified joint engagement states, using a mutually exclusive and exhaustive timed-event coding system described in Bottema-Beutel et al. (2014). In the second pass, coders divided supported joint engagement into higher- and lower-order variants. In a final pass, a 5-second partial interval coding system was used to record intervals in which the caregiver provided a follow-in utterance. Event and interval coded files were then merged together into a single file using ProCoder Merger (Tapp, 2013). The number of intervals in which caregivers provided follow-in utterances during HSJE was then tallied for each file using MOOSES software (Tapp, 2003).

Independent coders overlapped on 20% of randomly-selected files to calculate inter-rater reliability. Two-way random-effects models were used to calculate absolute agreement intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for each coded variable. Individual ICCs were in the excellent range for all variables; .98 for supported joint engagement, .87 for HSJE, and .91 for follow-in utterances.

Data analysis procedures

All analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software (StataCorp, 2014). For each variable, missing data occurred < 10% of the time; listwise deletion was used to handle missing data. To examine cross-modal longitudinal relations according to group status, two multiple regression analyses were conducted. For the first model, later expressive vocabulary was entered as the outcome, and gender, chronological age, early receptive vocabulary, group, and a group by early receptive vocabulary interaction term were entered as predictors. For the second model, later receptive vocabulary was entered as the outcome, and gender, chronological age, early expressive vocabulary, group, and a group by early expressive vocabulary interaction term were entered as predictors. Pair-wise Pearson’s correlations among continuous variables were computed prior to conducting each regression model (see Table 3). Correlations between predictor and outcome variables were significant and in the expected (positive) direction. Intercorrelations among predictors were not sufficiently high to warrant concerns regarding multicollinearity (i.e., were ≤ .8). Variance inflation factors were computed following each regression, and confirmed this assumption (i.e., were ≥ 10) (Mason and Perreault, 1991). Both regression models showed evidence of heteroscedasticity, so robust standard error estimation was used. Unlike ordinary least squares estimation, this procedure uses sandwich estimators, which do not impose assumptions regarding error variance (Hayes and Cai, 2007).

Table 3.

Intercorrelations among Continuous Study Variables by Group

| TD (n = 46) | ASD (n = 59) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 1. Time 1 Chronological Age | ||||||||||

| 2. Early Expressive Vocabulary | .62*** | .22 | ||||||||

| 3. Later Expressive Vocabulary | .40** | .49*** | .19 | .66*** | ||||||

| 4. Early Receptive Vocabulary | .46** | .62*** | .55*** | .24 | .73*** | .53*** | ||||

| 5. Later Receptive Vocabulary | .30* | .38** | .82*** | .55*** | .14 | .51*** | .71*** | .63*** | ||

| 6. Early HSJE + FI | .36* | .34* | .39** | .34* | .35* | .02 | .17 | .47*** | .43*** | .41** |

Note. Vocabulary was assessed using the MacArthur Bates Communicative Development Inventories. ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; HSJE + FI = Higher-Order Supported Joint Engagement with Caregiver Follow-in Utterances; TD = Typically Developing.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

To determine if the longitudinal, cross-modal associations found to differ between groups could be explained by an indirect effect of HSJE + FI that is stronger in the ASD as compared to the TD group (RQ3), a moderated mediation analysis was conducted using procedures described by Hayes (2013). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to generate standardized coefficients for each path in the model. Bootstrap procedures were used to generate bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effects (i.e., the product term of the a and b path). Group membership was tested as a moderator on the association of HSJE +FI with later vocabulary controlling for early vocabulary (i.e., the b path) because we hypothesized that children with ASD might be more dependent on FI being presented in HSJE than children with TD. Computing bootstrapped confidence intervals is considered an improvement upon those computed using t- or z-distributions, because it better reflects the sampling distribution of the indirect effects (Hayes, 2013).

Results

Cross modal, longitudinal regressions

The first regression indicated that early receptive vocabulary size was a significant predictor of later expressive vocabulary size, but the moderating effect of group did not reach statistical significance (p = .10 for the interaction term). Gender and chronological age were not significant. The second regression supported our hypothesis that early expressive vocabulary size was a significant predictor of later receptive vocabulary size, and the significant positive interaction term indicate that this association was stronger in the ASD group as compared to the TD group. Again, gender and chronological age were not significant. See Table 4 for coefficients and standard errors for each regression, and Figures 3 and 4 for regression lines generated from each model.

Table 4.

Results of Cross modal Regression Analyses for Effects of Early Vocabulary Size on Later Vocabulary Size, with Group as a Moderator

| Coefficient | Robust SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Later Expressive Vocabulary Size (ASD n = 59, TD n = 46) | ||

| Early Receptive Vocabulary | 0.80*** | 0.20 |

| Gender (Female = 1) | 18.87 | 24.21 |

| Group (ASD = 1) | −109.01† | 60.18 |

| Time 1 Chronological Age | 1.05 | 1.71 |

| Group X Early Receptive Vocabulary | −0.39 | 0.25 |

| Constant | 92.10** | 31.58 |

| Later Receptive Vocabulary Size (ASD n = 56, TD n = 46) | ||

| Early Expressive Vocabulary | 0 72*** | 0.20 |

| Gender (Female = 1) | 18.63 | 17.64 |

| Group (ASD = 1) | −156.53** | 52.96 |

| Time 1 Chronological Age | −0.55 | 1.93 |

| Group X Early Expressive Vocabulary | 1.31* | 0.56 |

| Constant | 297.30*** | 29.66 |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Figure 3.

Association between early receptive vocabulary size and later expressive vocabulary size, with group as a moderator.

Figure 4.

Association between early expressive vocabulary size and later receptive vocabulary size, with group as a moderator.

Moderated mediation analysis

In an attempt to further explore the different associations between early expressive vocabulary and later receptive vocabulary for the ASD and TD groups, an exploratory SEM model was computed with HSJE + FI as an indirect effect, and with group as a moderator of the b path. Since gender and chronological age were not found to be significant in the regression models, they were not included in the mediation models. This analysis showed that the a path and group-moderated b path were significant. Standardized regression coefficients are indicated in the path diagram in Figure 5. The bootstrap, bias corrected method for generating the conditional indirect effect (a*b) indicated that the indirect effect was significant for the ASD group, not significant in the TD group, and non-overlapping between groups. This confirmed that the mediating effect of HSJE + FI on the association between early expressive vocabulary and later receptive vocabulary is moderated by group. Coefficients and standard errors are given in Table 5.

Figure 5.

Indirect effect of early expressive vocabulary size on later receptive vocabulary size, through early HSJE + FI, with group moderating the b path. Values are standardized coefficients from a structural equation model. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; HSJE + FI = Higher-order supported joint engagement with caregiver follow-in utterances.

Table 5.

Conditional Indirect Effects (a*b) from Bootstrap Method with Percentile CIs (5,000 replications)

| Observed Coef. | BC SE | BC 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TD | .11 | .005 | −.02, .28 |

| ASD | .57 | .010 | .29, 1.38 |

Note. ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; BC = Cias-Corrected; CI = Confidence Interval; Coef = Coefficient; SE = Standard Error; TD = Typically Developing.

Discussion

This study examined associations across vocabulary modalities over an eight month period, in young children with ASD and TD children who were initially matched on expressive and receptive vocabulary sizes. Within the constraints of correlational methods, we also examined whether children with ASD relied more on HSJE + FI to acquire receptive vocabulary than the TD children. This study corroborates and extends previously untested assumptions regarding longitudinal associations across vocabulary modalities in children with ASD that may differ in degree from associations in children with TD (Woynaroski, Yoder, & Watson, 2016).

Results did not support our first hypothesis, that group would moderate associations between early receptive vocabulary and later expressive vocabulary, favoring the TD group. However, the sign of the coefficient for the interaction term was in the expected direction, and the p-value was near the critical value for significance (p = 0.10). It is therefore possible that subsequent studies with larger sample sizes may uncover small, but significant group differences in associations that bear out our prediction. It is also possible that the influence of early receptive vocabulary on later expressive vocabulary is similar for children with ASD and TD children.

Results supported our second hypothesis, that the association between early expressive vocabulary and later receptive vocabulary is stronger for children with ASD as compared to TD children in the early phases of word learning. Woynaroski, Yoder, and Watson (2016) proposed that expressive vocabulary may ‘drive’ later receptive vocabulary in children with ASD, because larger expressive vocabularies may index an ability to reciprocally collaborate with an interaction partner within HSJE. Further, caregivers of children with larger expressive vocabulary sizes may more readily provide follow-in utterances during HSJE episodes. This would result in enhanced opportunities for learning new receptive vocabulary. In contrast, typically developing children may not require such specific language-learning opportunities in order for expressive vocabulary to impact receptive vocabulary over time.

We tested this hypothesis in the context of a moderated mediation model, and did indeed find that HSJE + FI mediated the association between early expressive vocabulary size and later receptive vocabulary size, but only for the ASD group. Our findings show that the association between early HSJE + FI and later receptive vocabulary (i.e., the, b path in the mediation model) was significantly lower for TD children relative to children with ASD. The latter could occur because TD children might be better able to process linguistic input in many different interactional formats, which would greatly increase the frequency of occasions for word learning. It is possible that some children with ASD require very specific caregiver scaffolding in order to map words to their referents and make connections regarding what words mean in context.

Study strengths and limitations

A relative strength of this study is that the two samples were group-wise matched on two important dimensions (initial expressive and receptive vocabulary size) and approximately matched on mental age, limiting the extent to which variables that are not of interest to the study could explain our findings. An additional strength is the temporal precedence for the expressive vocabulary and HSJE + FI variables relative to receptive vocabulary. However, there are several limitations to the study design that should also be noted.

First, participants were not individually matched on control variables. Pairwise matching is a more rigorous way to match groups, and is particularly helpful in ruling out alternative explanations when between-group differences in associations are of interest. However, pairwise matching on multiple variables is extremely challenging and can result in non-representative samples of a population. Future research with individually matched groups should be conducted to confirm these findings.

Second, like all intact group comparison designs, other variables on which the samples were not matched may have influenced group differences in associations. Such “third variable explanations” could include demographic factors such as socio-economic status (Hoff, 2003) or child factors such as nonverbal mental age. One way to rule out some of the third variable explanations is to include a third comparison sample (e.g., children with developmental delay without ASD). Doing so would determine whether the particularly strong association between early expressive vocabulary and later receptive vocabulary is specific to children with ASD. In this analysis, however, we did not seek to test whether the pattern of associations was specific to ASD, as opposed to shared by other children with disabilities. A related issue is that it is possible that caregivers of children with ASD may have been less sure of their children’s receptive vocabularies than caregivers of TD children, because children with ASD may be less likely to explicitly respond and demonstrate their receptive vocabularies. This may have impacted our group-difference findings.

Third, the tests of between-group differences in associations did not account for concurrent associations between expressive and receptive vocabulary at both time points, or for associations within each variable across time. Such “cross panel analyses” are quite conservative methods of controlling common alternative explanations for differences between associations. However, they can result in controlling so much of the variance that analyses become underpowered, thus increasing type II error rates. Future research with larger sample sizes that is sufficiently powered to detect group differences while accounting for these variances is needed to increase the internal validity of the current study findings. Ultimately, like all correlational design, we cannot rule out all alternative explanations for the associations, and thus await future experiments to determine if the associations represent the causal influence of early predictors on later outcomes.

Fourth, the children with ASD were selected for inclusion in the larger study because they were language delayed, and had initially very low expressive vocabulary sizes. Developmental trajectories of language are known to differ between sub-populations of children with ASD (Pickles et al., 2014), so our findings can only be extended to children who are similar to those we included.

Fifth, we were unable to establish temporal precedence for the predictor variable (expressive vocabulary size) in relation to the mediator variable (HSJE + FI), as these variables were measured concurrently. Future research with at least three time points (with the mediator variable measured at a time point between the predictor and outcome) could more confidently assert that expressive language leads to an increase in HSJE + FI, rather than the reverse. Additionally, a single eight month lag between assessments is a relatively short period for predicting future vocabulary across modalities, particularly in children with ASD. A more complete quantification of cross-modal influences could be captured with additional time points, as the association we examined may change throughout early and late childhood. Prior research has, however, shown that cross-modal vocabulary associations appear to remain relatively stable into later childhood (Bornstein and Hendricks, 2012).

Finally, we acknowledge that HSJE + FI was measured during a brief caregiver-child play session, and we are therefore unable to provide information about how frequently this form of engagement occurs over the course of a typical day for our sample. However, developmental constructs are routinely measured using assessments similar to ours, which involve sampling phenomena of interest in brief, observational procedures (e.g., Adamson et al., 2009). Importantly, such observations are merely samples of interaction style and thus do not afford estimates of the absolute rates or even proportional rates that typically occur. Instead, observational variables used to quantify generalized behavioral tendencies enable ranking (or evaluation of the relative standing) of participants on the measured phenomena, which is the type of information needed to answer our particular research questions. More on this logic is present in Yoder & Symons (2010).

Implications for future research

We now discuss the ways in which a clearer understanding of how vocabulary development differs between children with ASD and TD children will allow researchers to more specifically tailor intervention formats to meet the unique needs of children with ASD. Many children with ASD have receptive vocabulary sizes that are smaller than expected given their expressive vocabulary size (e.g., Woynaroski, Yoder, & Watson, 2016). Identifying factors that leverage existing abilities (i.e., expressive vocabulary) to improve lagging development on other abilities (i.e., receptive vocabulary) may bring expressive and receptive vocabulary levels in line with more typical expectations. Additionally, targeting an influential mediator on the path from expressive to receptive vocabulary may be an effective strategy for doing so. Of note is that HSJE + FI, the mediator we identified as important for children with ASD, is a malleable factor as it involves efforts of the caregiver. Caregivers are increasingly being recognized as effective administrators of early intervention supports for young children with ASD (Green et al., 2010). Of particular relevance to our study is that caregivers are able to increase the amount of time they jointly engage with their child with ASD after caregiver training (Kasari et al., 2010). Interventions could be designed so that caregivers (or other adult interventionists) support the child in entering HSJE at increasing frequencies and durations. If caregivers are given trainingon: (a) the importance of HSJE, (b) how to identify when it occurs in their interactions with their children, (c) how to consistently respond within this state, and (d) how to purposefully arrange the types of play routines in which the child is able to demonstrate HSJE, it may be possible to maximize the probability that children with ASD process the linguistic input parents provide.

Although there are well-designed intervention studies that show increases in joint engagement correlate with concomitant or later increases in language, these studies combine several different types of joint engagement, and do not record caregiver utterances during the engagement state (i.e., Kasari et al., 2008). Refining measures of joint engagement so that components critical to vocabulary development are included may increase the impact of these interventions on vocabulary outcomes. The HSJE variable we examined contains elements of reciprocity from the child; this may be an important component of engagement states that are influential on receptive vocabulary development. Therefore, targeting interaction formats where the child is able to reciprocally collaborate in the activity with the adult, even if they are not visually referencing the adult, may be a critical ‘active ingredient’ of engagement-based interventions.

The potential role of expressive vocabulary size on later receptive vocabulary size through HSJE + FI will need to be clarified in future experiments designed to more definitively test causal mechanisms. It is possible that caregivers are more likely to provide follow-in utterances within HSJE if their children have larger expressive vocabularies, which would then lead to later receptive vocabulary gains. Within the context of a randomized control trial, caregivers could be encouraged to engage the child within an HSJE + FI format, even if the child has quite low expressive vocabulary. For these children, arranging enticing activities that allow for collaboration and reciprocity with an adult, but that are tailored to the child’s interests, may be a critical intervention component that allows for a shift in participation from lower forms of supported joint engagement (LSJE) to forms of engagement more conducive to language development (i.e., HSJE) (Kasari et al., 2008). This approach may ‘level the playing field,’ so that even children with initially low expressive vocabularies will experience gains in receptive vocabulary beyond change found in a control group.

Alternatively, it could be that expressive vocabulary size is indexing a more general child propensity for high-level engagement, in which case it may be more difficult for caregivers to engage children who have low expressive vocabulary sizes in this format. Still, it may be that these children would benefit from even small increases in HSJE + FI relative to a control group of children with similar expressive vocabulary sizes. In the future, more specific strategies to increase the frequency and duration with which children with initially low expressive vocabulary sizes engage in HSJE + FI should be developed and tested.

Finally, additional research could be conducted to specify even further the types of engagement formats, and caregiver utterances provided within engagement formats, that are best suited to mediate the association between expressive and receptive vocabulary in young children with ASD. We focused on HSJE + FI because of recent literature indicating that this is a particularly facilitative engagement format (Adamson et al., 2009; Bottema-Beutel et al., 2014). It is however possible that other, more frequently occurring engagement formats also influence this pathway. We also examined ‘follow-in’ utterances as a broad category of caregiver talk, but it is possible that follow-in comments and follow-in directives, when provided during HSJE, serve different purposes in development. Indeed, recent work has demonstrated that follow-in directives better elicit child play with toys than follow-in comments (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2017). It may be the case that one or the other type of follow-in utterance provided within HSJE is superior in facilitating receptive vocabulary development.

Conclusion

This study offers several important and novel findings. First, it supports the previously untested assumptions that longitudinal, cross-modal, vocabulary associations found in children with ASD are indeed atypical, at least in regards to the strength of associations in the early expressive to later receptive direction. Second, it identified an important mediator, HSJE + FI, which appears to more strongly mediate the pathway between early expressive and later receptive vocabulary in children with ASD as compared to TD. The critical importance of HSJE + FI on this pathway for children with ASD, but not TD children, might at least partially explain the superior associations between early expressive vocabulary and later receptive vocabulary in children with ASD. Future experiments are needed to test whether this hypothesized causal relation exists in children with ASD in the early stages of language learning.

Footnotes

Note that LSJE differs from object engagement, where the child plays with objects without influence from the parent.

Contributor Information

Kristen Bottema-Beutel, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, USA.

Tiffany Woynaroski, Department of Hearing and Speech Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, USA.

Rebecca Louick, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, USA.

Elizabeth Stringer Keefe, Lynch School of Education, Boston College, USA.

Linda R. Watson, Division of Speech and Hearing Sciences, Department of Allied Health Sciences, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, USA

Paul J. Yoder, Department of Special Education, Vanderbilt University, USA

References

- Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Deckner DF., & Romski M (2009). Joint engagement and the emergence of language in children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 84–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-IV-TR. Washington, DC: APA. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R, & Adamson L (1984). Coordinating attention to people and objects in mother-infant and peer-infant interaction. Child Development, 55, 1278–1289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict H (1979). Early lexical development: Comprehension and production. Journal of Child Language, 6(2), 183–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, & Hendricks C (2012). Basic language comprehension and production in > 100,000 young children from sixteen developing nations. Journal of Child Language, 39, 899–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottema-Beutel K (2016). Associations between joint attention and language in autism spectrum disorder and typical development: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Autism Research, 9(10), 1021–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottema-Beutel K, Malloy C, Lloyd B, Louick R, Nelson LJ, Watson LR, & Yoder PJ (2017). Sequential associations between caregiver talk and child play in autism spectrum disorder and typical development Child Development. Advance Online Publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottema-Beutel K, Yoder PJ, Hochman J, & Watson LR (2014). The role of supported joint engagement and parent utterances in language and social communication development in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(9), 2162–2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale P Reznick J, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung J, … Reilly J (2003). MacArthur communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie-Lynch K, Sepeta L, Wang Y, Marshall S, Gomez L, Sigman M, & Hutman T (2012). Early childhood predictors of the social competence of adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 161–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Charman T, McConahchie H, Aldred C, Slonims V, Howlin P, …Pickles A (2010). Parent-mediated communication-focused treatment in children with autism (PACT): A randomized controlled trial. The Lancet, 375(9732), 19–25. doi: 10.1015/S0140-6736(10)60587-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Cai L (2007). Using heteroscedasticity-consistent standard error estimators in OLS regression: An introduction and software implementation. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 709–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E (2003). The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development, 74(4), 1368–1378. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Gulsrud AC, Wong C, Kwon S, & Locke J (2010). Randomized controlled caregiver mediated joint engagement intervention for toddlers with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1045–1056. doi: 10.1007/s10803-101-0955-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Paparella T, Freeman SN, & Jahromi L (2008). Language outcome in autism: Randomized comparison of joint attention and play interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH Jr., Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, …Rutter M (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, & Fritz MS (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CH, Perrault WD Jr. (1991). Collinearity, power, and interpretation of multiple regression analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 268–280. [Google Scholar]

- McDuffie A, & Yoder P (2010). Types of parent verbal responsiveness that predict language in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 1026–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mervis CB & Klein-Tasman BP (2004). Methodological issues in group-matching designs: α levels for control variable comparisons and measurement characteristics of control and target variables. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(1), 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy P, Sigman M, Ungerer J, & Sherman T (1986). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27, 657–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish-Morris J, Hennon EA, Hirsch-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM, & Tager-Flusberg H (2007). Children with autism illuminate the role of social intention in word learning. Child Development, 78(4), 1265–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles A, Anderson DK, & Lord C (2014). Heterogeneity and plasticity in the development of language: A 17-year follow-up of children referred early for possible autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(12), 1354–1362. Doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Paul R, Black LM, van Santen JP (2011). The hypothesis of apraxia of speech in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 405–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller M, Hutman T, Sigman M (2014). A parent-mediated intervention to increase responsive parental behaviors and child communication in children with ASD: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 540–555. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1584-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller M, & Sigman M (2002). The behaviors of parents and children with autism predict the subsequent development of their children’s communication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32, 77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller M & Sigman M (2008). Modeling longitudinal change in the language abilities of children with autism: Parent behaviors and child characteristics as predictors of change. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1691–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. (2015). Stata Statistical Software: Release 14.College Station TX: StataCorp LP. Swettenham J, Baron-Cohen S, Charman T, Cox A, Baird G, Drew A, & … Wheelwright S (1998). The frequency and distribution of spontaneous attention shifts between social and nonsocial stimuli in autistic, typically developing, and nonautistic developmentally delayed infants. Journal of Child Psychology And Psychiatry, 39(5), 747–753 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H & Kasari C (2013). Minimally verbal school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder: the neglected end of the spectrum. Autism Research, 6(6). 468–478. doi: 10.1002/aur.1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, Rogers S, Cooper J, Landa R, Lord C Paul R, … Yoder P (2009). Defining spoken language benchmarks and selecting measures of expressive language development for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 52(3), 643–652. Doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0136) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapp JT (2003). Multi-Option Observation System for Experimental Studies [Computer software and manual]. http://mooses.vueinnovations.com/

- Tapp JT (2003). ProcoderDV [Computer software and manual]. http://procoder.vueinnovations.com/sites/default/files/public/d10/ProcoderDVManual_0.pdf.

- Tapp JT (2013). Procoder merger [computer software]. Nashville,TN: Vanderbilt Kennedy Center. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M (1999). The cultural origins of human cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watt N, Wetherby A, & Shumway S (2006). Prelinguistic predictors of language outcome at 3 years of age. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 49(6), 1224–1237. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/088) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woynaroski T, Yoder PJ, & Watson LR (2016). Atypical cross-modal profiles and longitudinal associations between vocabulary scores in initially minimally verbal children with ASD. Autism Research, 9(2), 301–310. doi: 10.1002/aur.1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woynaroski T, Watson L, Gardner E, Newson CR, Keceli-Kaysili B, & Yoder PJ (2016). Early predictors of growth in diversity of key consonants used in communication in initial preverbal children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(3), 1013–10124. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2647-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, & Symons F (2010). Observational measurement of behavior. New York, NY: Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yoder PJ, Watson LR, & Lambert W (2015). Value-added predictors of expressive and receptive language growth in initially nonverbal preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(5), 1254–1270. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2286-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]