Abstract

Introduction

Efficient repositioning of centralized nuclei following injury has long been assumed, with centralized nuclei frequently cited as indicators of ongoing regeneration. However, reports of centralized nuclei that persist following full recovery of fiber area and muscle force production call into question the time course of nuclear repositioning.

Methods

We evaluated regeneration following cardiotoxin-induced damage in 10 week old mice by quantifying intracellular and extracellular pathology at 2 and 94 weeks post-injection.

Results

Centrally nucleated fibers were still prevalent 94 weeks post-injection, representing more than 25% of muscle fibers. Areas with >90% centrally nucleated fibers could still be identified. Extra-myocellular indicators of regeneration (e.g. fibrosis and fatty infiltration) also remained significantly elevated at the 94 week timepoint.

Discussion

These findings indicate that not all nuclei are repositioned at the conclusion of induced muscle regeneration.

Keywords: Cardiotoxin, Regeneration, Centralized Nuclei, Nuclear Positioning, Fatty Infiltration

Introduction

The central positioning of nuclei in muscle fibers has been used as a marker of regeneration for over 50 years1,2. In animal models of induced injury, such as toxin injection, chains of nuclei within the center of small diameter fibers were noted to resemble embryonic development1,3. This led to the general conclusion that fiber regeneration recapitulates fiber development and that, during regeneration, nuclei are eventually relocated to the fiber periphery4,5. This conclusion was supported by reports of decreased centralization as regenerating fibers matured1,3,6, however none of these studies looked at a sufficiently distant timepoint to see full resolution of central nucleation – it was assumed that all nuclei would eventually become peripheral. In fact, operating on this assumption, many studies examining human biopsies identify centrally nucleated fibers (CNFs) as fibers actively undergoing regeneration7–9.

A few reports of persistent CNFs challenge the notion that these are markers of ongoing repair, suggesting that central nucleation could be a permanent pathological feature signifying past regeneration events10–13. However, they could also be explained by a lengthy nuclear repositioning mechanism that lags the recovery of fiber size and function by several months.

In this study, we induced muscle regeneration in young mice and then assessed the persistence of CNFs at 2 years, near the end of the lifespan. We hypothesized that some nuclei would remain mis-positioned and that these are an intracellular reflection of inefficient regeneration, similar to the extracellular development of fibrosis and intramuscular fat.

Methods

Experimental Design

Experiments were performed on tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of 16 10 week old C57BL/6J male mice (Jackson Laboratory). Mice were anesthetized, their hindlimbs sterile prepped and their tibialis anterior (TA) muscles given bilateral intramuscular injections through the skin of 10 μL of either 10 μM cardiotoxin (CTX) solution – a myotoxin that induces focal muscle necrosis and regeneration14 (n=8) - or sterile saline (SAL, n=8). Treatment groups were subdivided (n=4) by time to muscle harvest – 2 weeks (2W) or 94 weeks (94W). One mouse in the 94W CTX group died of natural causes. All procedures were performed in accordance with the NIH’s Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Washington University School of Medicine.

Muscle Harvest and Analysis

At the time of sacrifice TA muscles were dissected bilaterally. One TA was frozen and cryosectioned in the central third of the muscle belly as previously described in detail15. Sections were stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) and Picrosirius Red according to standard protocols described previously16. Overlapping images were taken of each H&E stained section and digitally registered to reconstruct the full TA cross-section. Fibers with centralized nuclei were identified and manually marked on reconstructions. Collagen area fraction was averaged from two Picrosirius Red stained images using IsoData automated thresholding17 and dividing the number of identified red pixels by the total pixel count. Fiber cross-sectional areas were outlined by hand on Picrosirius Red stained images. All image quantification was performed using ImageJ software (NIH).

The second TA was decellularized and stained with Oil Red O as previously described16. Oil Red O stain was extracted with isopropanol and the optical density determined (Synergy II, Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Statistical Analysis

Data were compared using Graphpad Prism (San Diego, CA) across treatment and age by two-way ANOVA and considered significant (α) at p<0.05. Individual groups were compared using Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

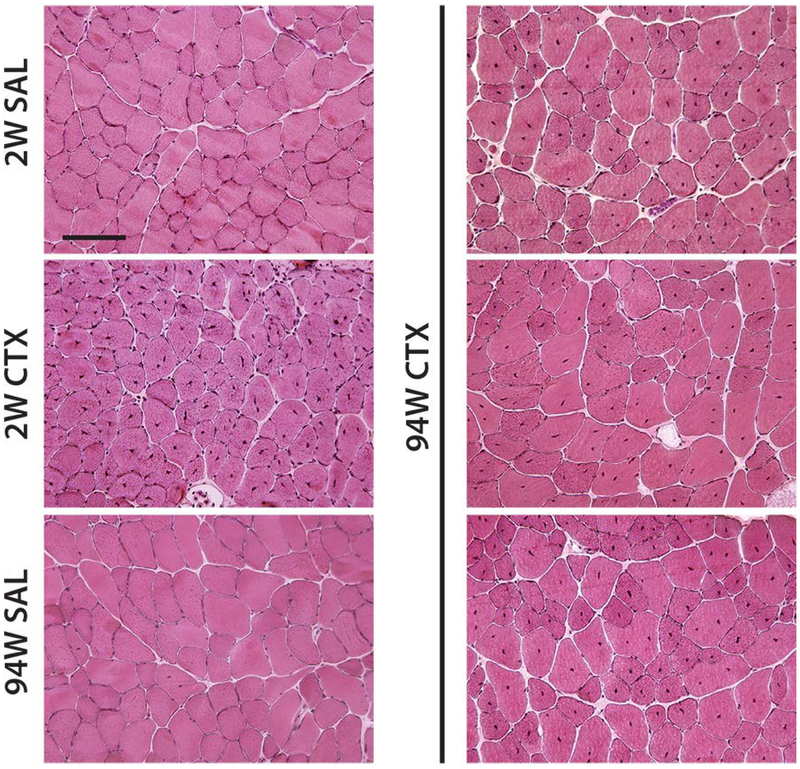

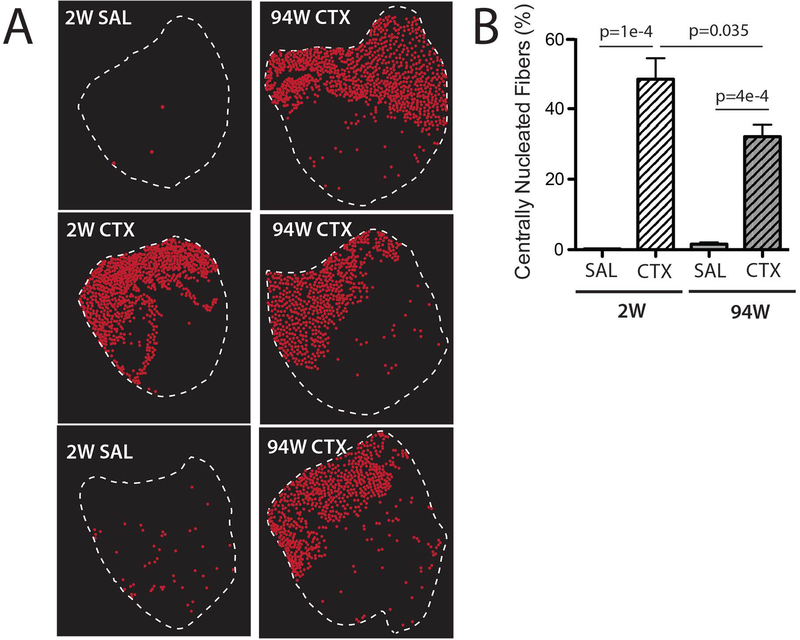

TA muscle harvested 2 weeks following CTX injection exhibited areas of high concentration of CNFs (Fig 1; 2W CTX) in line with previous reports18. Similarly, at 94 weeks post CTX, large areas could be identified in all muscles where >90% of fibers exhibited central nucleation (Fig 1; 94W CTX). No such areas were present in SAL injected controls (Fig 1; 2W SAL, 94W SAL). Mapping of the distribution of CNFs revealed that areas of dense central nucleation covered ~30–60% of the cross-section in both 2W and 94W CTX groups (Fig 2A), reflecting focal delivery of CTX. By comparison, CNFs in SAL groups were sporadic and evenly distributed throughout the cross-section. Quantification of the percentage of CNFs revealed a significant main effect of CTX with a significant interaction between CTX and age (Fig 2B). Post-testing revealed that both CTX groups had significantly elevated CNFs compared with age matched SAL groups and that there were significantly more CNFs with CTX treatment at 2 weeks than at 94 weeks.

Figure 1.

Representative H&E stained sections from cardiotoxin (CTX) and saline (SAL) injected TA muscles at 2 weeks (2W) and 94 weeks (94W) post injection. Centralized nuclei are abundant in CTX injected muscle at both 2W (center left) and 94W (right column, each image represents the TA muscle from a different mouse in this group), but rare in SAL groups. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 2.

A. The full TA muscle cross-section was reconstructed from individual H&E stained sections and centrally nucleated fibers (CNFs) marked (red dots). CNF marks are displayed within the TA perimeter outline (dotted white line) to create a visual map. Areas of high concentration of CNFs are evident in both CTX groups while CNFs are fewer and sporadically distributed in SAL groups. The left column is a representative map from the indicated group while the right column includes TA muscles from all 3 mice in the 94W CTX group for comparison. B. Quantification of CNFs as a percentage of total fibers. CTX groups had dramatically more CNFs than age-matched SAL groups, with significantly more CNFs at 2 weeks than at 94 weeks. Data are mean ± SEM.

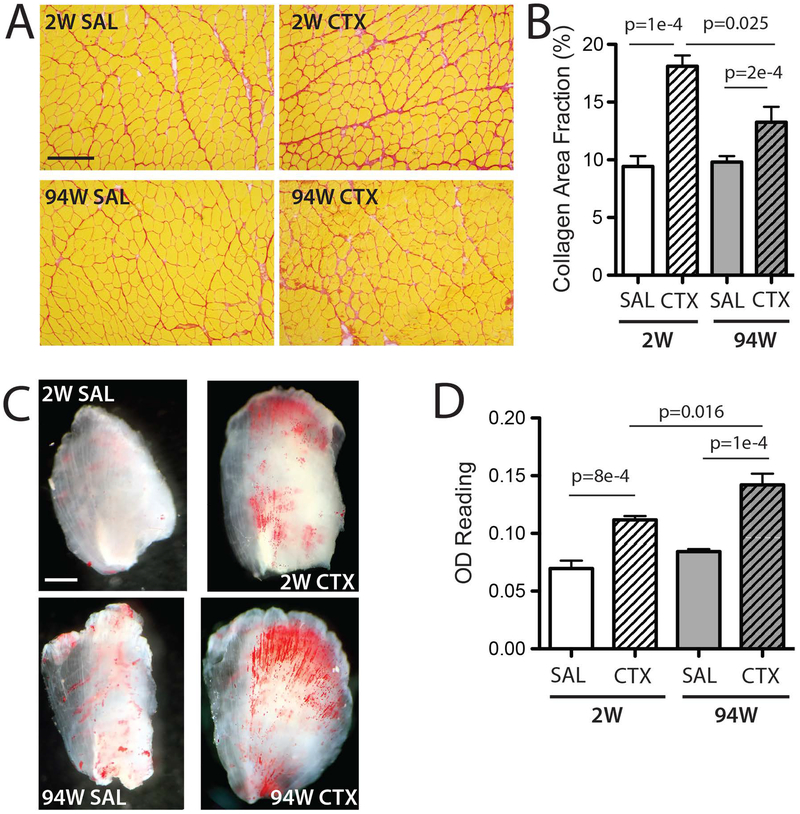

Classical extra-myocellular features of incomplete regeneration - fibrosis and fatty infiltration - were also found to persist to some degree in the 94W group. Picrosirius red stained sections showed qualitatively more collagen in CTX groups (Fig 3A) which when quantified demonstrated significant main effects of CTX and age with a significant interaction (Fig 3B). Similarly, Oil Red O staining of decellularized TA muscles showed a qualitative increase in stained lipid in both CTX groups with a distinctive fiber-direction alignment of intramuscular lipid (Fig 3C). Quantification of Oil Red O retention demonstrated significant main effects of CTX and age with a significant interaction (Fig 3D). TA weight (2W-SAL:50.0±1.3mg, 2W-CTX:53.7±1.1mg, 94W-SAL:66.8±3.0mg, 94W-CTX:70.95±3.1mg), fiber number (2W-SAL:2133.3±150.0, 2W-CTX:2436.0±178.5, 94W-SAL:2165.8±97.5, 94W-CTX:2470.0±101.0) and average fiber cross-sectional area (2W-SAL:1870.3±227.1μm2, 2W-CTX:1708.4±73.4 μm2, 94W-SAL:2149.±133.8 μm2, 94W-CTX:2276.0±166.6 μm2) were not significantly different between treatment groups at either age. No gross histological evidence of ongoing regeneration in the form of inflammatory infiltration, necrotic fibers or small diameter fibers was detected in 94 week muscles.

Figure 3.

A. Picrosirius Red stained sections for visualization of extracellular matrix (red=collagen, yellow=muscle fibers). At 2 weeks, CTX muscles have uniformly increased collagen staining compared with SAL. At 94 weeks, focal areas of increased collagen staining can still be identified in the CTX group. Scale bar = 200 μm. B. Quantification of collagen area fraction from Picrosirius Red stained sections in areas of high CNF. Collagen area fraction is significantly elevated in both CTX groups compared with age-matched SAL, with significantly more area occupied by collagen at 2 weeks than at 94 weeks. C. Decellularized TA muscles stained with Oil Red O for visualization of the quantity and distribution of intramuscular adipocyte lipid (red). CTX muscles have qualitatively more lipid staining than SAL and lipid distribution appears aligned with the fiber direction while in SAL muscles, lipid staining tends to be concentrated around blood vessels. Scale bar = 1mm D. Optical density reading of extracted Oil Red O dye from constructs – a validated surrogate for lipid content16. Both CTX groups have significantly elevated OD readings compared with age-matched SAL, with a further significant increase from 2 to 94 weeks. Data are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

In response to CTX, muscle mounts a regenerative response that involves activating resident immune, satellite and interstitial cells that coordinate clearance of cellular debris, stabilization of the extracellular matrix and generation of new fibers, reviewed by Hardy et al.19. Histologically, the early phase of this response is characterized by extensive extracellular matrix proliferation, increased prevalence of intramuscular adipocytes and a preponderance of small diameter fibers with centrally localized nuclei11,18. The majority of these changes resolve during the later phases of regeneration. However, while cases of persistent fibrosis and fatty infiltration are prevalent in literature20,21, the longevity of intracellular structural changes has not been explored leading to mixed assumptions about the implications of a CNF5,9. In this report we demonstrate that, in addition to fibrosis and fatty infiltration, CNFs can persist for years following an injury, acting as an intracellular indicator of a past regenerative event.

The molecular mechanisms driving nuclear positioning during development are well defined in the fly and involve the motor proteins kinesin and dynein leading the nucleus along cytoskeletal microtubules as sarcomeres mature in the fiber center22,23, reviewed in detail by Folker et al.5. When a fiber is fully replaced during regeneration, it makes intuitive sense that nuclear positioning mechanisms would be conserved, though it has not been demonstrated. However, whether these mechanisms are also at play during repair or hypertrophy is unknown. Clearly some ability to position nuclei is maintained in adult regeneration and repair, since peripheral nuclei are abundant after induced regeneration and decreased centralization of donor myoblasts has been reported in regenerating host muscle over time6,7. However, the persistence of CNFs following regeneration suggests that the developmental mechanisms of nuclear positioning are less efficient in mature muscle. The reason for this may lie in mechanistic differences between regeneration and development. Since during regeneration, fibers are frequently repaired focally or built on the residual scaffold of damaged mature fibers24, incomplete clearance of cytoskeletal proteins or rebuilding of peripheral sarcomeres could physically impede the movement of central nuclei to the periphery. Future studies aimed at elucidating these “errors” will shed significant light on the extent to which developmental mechanisms are recapitulated during regeneration.

This study is unable to determine whether, following full resolution of the injury, centralized nuclei continue to be repositioned to the periphery. There were significantly more CNFs at 2 weeks post-CTX than at 94 weeks. However, this may reflect differences in localization and distribution of delivered CTX as this study is not longitudinal. Furthermore, the mechanism of CTX injury differs from other myotoxins19 and from other physiological injury modalities and care must be taken extrapolating these findings to all mechanisms of injury or, indeed, all muscles and all species. Thus, this study concludes only that not all nuclei are repositioned at the conclusion of CTX-induced regeneration in the mouse TA.

This study also demonstrates long-term persistence of fibrosis and intramuscular fat following induced muscle regeneration. The apparent permanence of these pathological features, persisting in an otherwise healthy mouse for the majority of its lifetime, has important implications. It suggests that once the injurious stimulus is removed and the initial repair is complete, the muscle has limited intrinsic capacity to rectify structural pathology. The physiological significance of the persistent pathology, particularly centralized nuclei, remains to be defined. Altered nuclear positioning elicited by depletion of dynein and kinesin has been demonstrated to decrease muscle contractile function in the fly22,23, but a direct link between CNFs and muscle contraction has not been established in mammals. Future work genetically manipulating nuclear repositioning mechanisms in mice will help elucidate the functional significance of CNF persistence.

Acknowledgements:

The author would like to thank Washington University Musculoskeletal Research Center (NIH P30 AR057235) and Tejaswi Makkapati for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- CNF

Centrally Nucleated Fiber

- TA

Tibialis Anterior

- CTX

Cardiotoxin

- SAL

Saline

- H&E

Hematoxylin & Eosin

Footnotes

Ethical Publication Statement: We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Clark WE An experimental study of the regeneration of mammalian striped muscle. J. Anat 80, 24–36.4 (1946). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiro AJ, Shy GM & Gonatas NK Myotubular myopathy. Persistence of fetal muscle in an adolescent boy. Arch. Neurol 14, 1–14 (1966). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmalbruch H The morphology of regeneration of skeletal muscles in the rat. Tissue Cell 8, 673–692 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson BM The regeneration of skeletal muscle. A review. Am. J. Anat 137, 119–149 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folker ES & Baylies MK Nuclear positioning in muscle development and disease. Front Physiol 4, 363 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaveri K et al. Patterns of repair of dystrophic mouse muscle: studies on isolated fibers. Dev. Dyn 216, 244–256 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gussoni E, Blau HM & Kunkel LM The fate of individual myoblasts after transplantation into muscles of DMD patients. Nat. Med 3, 970–977 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warhol MJ, Siegel AJ, Evans WJ & Silverman LM Skeletal muscle injury and repair in marathon runners after competition. Am. J. Pathol 118, 331–339 (1985). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubowitz V, Sewry CA & Lane RJM Muscle Biopsy (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson BM, Dedkov EI, Borisov AB & Faulkner JA Skeletal muscle regeneration in very old rats. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 56, B224–33 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Couteaux R, Mira JC & d’Albis A Regeneration of muscles after cardiotoxin injury. I. Cytological aspects. Biol. Cell 62, 171–182 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell CD & Conen PE Histopathological changes in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Neurol. Sci 7, 529–544 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiMario JX, Uzman A & Strohman RC Fiber regeneration is not persistent in dystrophic (MDX) mouse skeletal muscle. Dev. Biol 148, 314–321 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin Shiau SY, Huang MC & Lee CY Mechanism of action of cobra cardiotoxin in the skeletal muscle. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 196, 758–770 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer GA & Lieber RL Skeletal muscle fibrosis develops in response to desmin deletion. Am. J. Physiol., Cell Physiol 302, C1609–20 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biltz NK & Meyer GA A novel method for the quantification of fatty infiltration in skeletal muscle. Skelet Muscle 7, 1 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridler TW & Calvard S Picture thresholding using an iterative selection method. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics 8, 630–632 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahdy MAA, Lei HY, Wakamatsu J-I, Hosaka YZ & Nishimura T Comparative study of muscle regeneration following cardiotoxin and glycerol injury. Ann. Anat 202, 18–27 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy D et al. Comparative Study of Injury Models for Studying Muscle Regeneration in Mice. PLoS ONE 11, e0147198 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann CJ et al. Aberrant repair and fibrosis development in skeletal muscle. Skelet Muscle 1, 21 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vettor R et al. The origin of intermuscular adipose tissue and its pathophysiological implications. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 297, E987–98 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folker ES, Schulman VK & Baylies MK Translocating myonuclei have distinct leading and lagging edges that require kinesin and dynein. Development 141, 355–366 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metzger T et al. MAP and kinesin-dependent nuclear positioning is required for skeletal muscle function. Nature 484, 120–124 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chargé SBP & Rudnicki MA Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol. Rev 84, 209–238 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]