ABSTRACT

The vasculitides are a heterogeneous group of conditions typified by their ability to cause vessel inflammation with or without necrosis. They present with a wide variety of signs and symptoms and, if left untreated, carry a significant burden of mortality and morbidity. The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides (AAV) are three separate conditions – granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA; previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome). This review examines recent developments in the pathogenesis and treatment of AAV, focusing on developments in treatment following the introduction of rituximab, in particular.

KEYWORDS: ANCA, diagnosis, rituximab, treatment, vasculitis

Key messages

The ANCA-associated vasculitides (AAV) are rare multisystem autoimmune diseases, more common in older people and in men

Induction treatment for most patients with AAV should be with cyclophosphamide or rituximab and glucocorticoids

AAV should be considered to be a chronic disease needing long-term immunosuppressive therapy

Rituximab should be considered as an alternative induction agent for those at high risk of infertility and infection

The mortality remains high, and late death is due to cardiovascular disease, infection (secondary to treatment) and malignancy

Introduction

The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides (AAV) are a collection of relatively rare autoimmune diseases of unknown cause, characterised by inflammatory cell infiltration causing necrosis of blood vessels. The association between ANCA and vasculitis was first described in 1982, in a short report describing the clinical course of eight patients diagnosed with a segmental necrotising glomerulonephritis.1 The discovery of perinuclear and cytoplasmic patterns on indirect immunofluorescence (P-ANCA and C-ANCA) and the main specificities myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 (PR3) were recognised in the 1980s. The AAV comprise granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, previously known as Wegener’s granulomatosis), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome).

Classification and epidemiology

The American College of Rheumatology in 1990 developed classification criteria for GPA and EGPA. Definitions for the AAV were described at the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) in 1994 and were revised in 2012 (Table 1).2 The Chapel Hill group stress that the CHCC is a nomenclature system and not a set of classification or diagnostic criteria. The AAV are considered to be small vessel vasculitides but there is considerable overlap possible with respect to size of vessel involved. The conventional classification based on clinical phenotype has been challenged as there is now good epidemiological, genetic and clinical evidence to support a division based on ANCA subtype.3

Table 1.

2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference definitions for ANCA-associated vasculitis

| Definitions for ANCA-associated vasculitis | |

|---|---|

| ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) | Necrotising vasculitis, with few or no immune deposits, predominantly affecting small vessels (ie capillaries, venules, arterioles and small arteries), associated with MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA. Not all patients have ANCA. Add a prefix indicating ANCA reactivity, eg PR3-ANCA, MPO-ANCA, ANCA-negative. |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) | Necrotising granulomatous inflammation usually involving the upper and lower respiratory tract, and necrotising vasculitis affecting predominantly small to medium vessels (eg capillaries, venules, arterioles, arteries and veins). Necrotising glomerulonephritis is common. |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) | Eosinophil-rich and necrotising granulomatous inflammation often involving the respiratory tract, and necrotising vasculitis predominantly affecting small to medium vessels, and associated with asthma and eosinophilia. ANCA is more frequent when glomerulonephritis is present. |

| Microscopic polyangiitis | Necrotising vasculitis, with few or no immune deposits, predominantly affecting small vessels (ie capillaries, venules or arterioles). Necrotising arteritis involving small and medium arteries may be present. Necrotising glomerulonephritis is very common. Pulmonary capillaritis often occurs. Granulomatous inflammation is absent. |

ANCA = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; MPO = myeloperoxidase; PR3 = proteinase 3

Adapted from Jennette et al.2

GPA, MPA and EGPA have respective annual incidence rates of 2.1–14.4, 2.4–10.1 and 0.5–3.7 per million in Europe, and the prevalence of AAV is estimated at to be 46–184 per million.4 They are more common in those aged over 60 years and slightly more common in men. The 5-year survival rates for GPA, MPA and EGPA are estimated to be 74–91%, 45–76% and 60–97%, respectively.5

Clinical presentation

The clinical spectrum of the AAV is broad and hence the presentation can be quite varied, ranging from a skin rash to fulminant multisystem disease. Typical features of GPA include nasal crusting, stuffiness and epistaxis, uveitis, upper respiratory tract involvement and often, when in the context of an active urinary sediment, renal involvement. Patients with MPA are typically older and present with more severe renal disease than GPA together with rash and neuropathy. EGPA typically presents with a multisystem disease on a background of asthma, nasal polyposis and peripheral blood eosinophilia.

Investigation

The relative rarity and non-specific presentation of the AAV pose diagnostic challenges and often result in a significant diagnostic delay of more than 6 months in a third of patients. The clue to the diagnosis is often developing multisystem involvement; therefore, a very careful and systematic approach is required to make the diagnosis. A detailed history and examination is required; laboratory investigations should include assessments of inflammatory markers, kidney function (urea and electrolytes – always with urine dip assessment, quantification of urine protein leak and urine microscopy for red cell casts), serological testing including ANCA, antinuclear antibodies and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies (both systemic lupus erythematosus and Goodpasture’s syndrome can masquerade as AAV). Infection should also be excluded and the diagnosis of bacterial endocarditis considered and excluded. Chest X-ray should be undertaken. Computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be required to assess the chest, brain, orbits and ear, nose and throat structures in more detail. A biopsy should always be considered to confirm the diagnosis and exclude mimics. However, treatment should not necessarily be delayed simply to get a biopsy. Disease activity scores such as the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) can act as a useful aide memoire.6 BVAS should also be recorded to measure disease activity, but training should be undertaken so that this tool is used appropriately (available at www.bvasvdi.org).

The role of serial ANCA measurement in determining treatment during remission remains controversial. Some current evidence suggests patients in whom ANCA remains present or rises more than fourfold are at greater risk of relapse. It is accepted that more frequent structured clinical assessment should be performed rather than a change in therapy based solely on ANCA measurement.7

Treatment

Remission induction

The definition of remission has been standardised by the European Vasculitis Society/European League against Rheumatism (EUVAS/EULAR) group, who recommend that the definition of remission should be one of no detectable disease activity using a recognised scoring tool such as BVAS.8

The use of daily cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoids improved the dire prognosis of untreated AAV (>80% mortality at 1 year) to one of where long-term remission was possible but relapses and iatrogenic side effects were common. This changed the drive in the research agenda to limit cyclophosphamide exposure and, more recently, reduce cumulative glucocorticoid dosage.

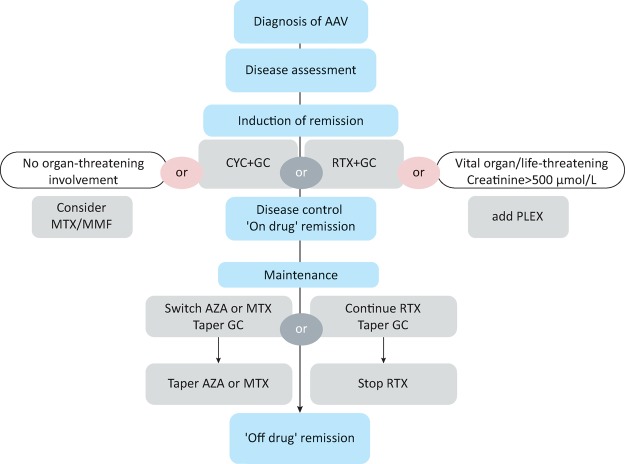

Induction of remission using cyclophosphamide (or rituximab) should be considered in all patients with new onset AAV. Other induction regimens using methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil should only be considered for patients with no evidence of organ or life-threatening disease; this is the minority of new patients. In patients presenting with a creatinine of >500 μmol/L, the addition of plasma exchange to high-dose glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide or rituximab should be considered. An algorithm for the treatment of patients with new onset AAV is given in Fig 1. The majority of trials have only included GPA and MPA patients; however, EGPA is generally treated using a similar approach.

Fig 1.

Algorithm for treating ANCA-associated vasculitis.

AAV = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides; AZA = azathioprine; CYC = cyclophosphamide; GC = glucocorticoids; MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; MTX = methotrexate; PLEX = plasma exchange; RTX = rituximab. Reproduced with permission from Ntatsaki et al.11

Cyclophosphamide

The CYCAZAREM (cyclophosphamide versus azathioprine for early remission phase of vasculitis) trial showed that oral daily cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg/day) with glucocorticoids for 3–6 months achieved remission in more than 90% of patients.9 Subsequently, the CYCLOPS trial showed that pulsed intravenous cyclophosphamide (10–15 mg/kg) was as effective at inducing remission as daily oral cyclophosphamide but with a lower cumulative dose of the drug, causing fewer side effects. Long-term follow-up of the trial participants revealed an increased risk of relapse in those participants who had received pulsed cyclophosphamide, but importantly no differences in renal function or survival.10 However, because of the reduced total dose of cyclophosphamide associated with pulsed regimens, these are favoured in recent guidelines.11,12 Mesna to reduce uroepithelial malignancy and haemorrhagic cystitis should be considered for all patients.

Rituximab

Rituximab in AAV has been tested in two randomised controlled trials: RAVE and RITUXVAS.13,14 In both studies participants initially received high-dose glucocorticoids with subsequent dose tapering. The rituximab dose in both studies was 375 mg/m2 of body surface area, once a week for four infusions. In both trials, rituximab was non-inferior to cyclophosphamide and appeared more effective for relapsing disease in RAVE. In the RAVE trial, a better response was seen in PR3 positive patients.15

An alternative regimen of 1 gm given on two occasions 2 weeks apart has been widely used and shown to be as effective.16 In the UK, rituximab may be used in AAV for primary induction in the following circumstances:

for remission induction in newly-diagnosed patients when avoiding cyclophosphamide is desirable because of relative contraindications, such as previous uroepithelial malignancy, premenopausal women who have not completed their family, previous cyclophosphamide treatment or inability to complete a planned treatment course of cyclophosphamide due to allergy or intolerance

when cyclophosphamide has not worked (after 3–6 months of treatment), either failure to control active disease or disease progression has occurred during the treatment course

for treatment of first relapse

for remission maintenance when rituximab has been used to induce remission or when alternative remission maintenance agents (azathioprine, methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil) have been ineffective, or have not been tolerated because of toxicity.

Although the RAVE13 and RITUXVAS14 trials only included GPA and MPA patients, there is anecdotal evidence from case series that rituximab may be effective in EGPA.

Remission maintenance

After successful remission induction, guidelines recommend withdrawing the initial immunosuppressive agent and commencing a maintenance regimen with either azathioprine or methotrexate.11,12 However, data are lacking on the precise duration of the maintenance regimen and recommendations have been made based on expert consensus. Early cessation of therapy (<1 year) is associated with an increased risk of relapse.17 It is generally advised that maintenance therapy is continued for at least 18–24 months before being gradually withdrawn. In general, attempts at reduction of glucocorticoids should be made prior to tapering of the immunosuppressive remission maintenance agent. The risk of relapse is greater in patients who are PR3-ANCA positive at presentation and in those who remain PR3-ANCA positive when switched from induction to maintenance immunosuppression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors increasing the risk of relapse

| Clinical presentation | Serology | Treatment related |

|---|---|---|

| GPA | PR3-ANCA at presentation | Steroid withdrawal |

| ENT involvement | ANCA positive after induction | Immunosuppressive withdrawal |

| Better renal function (creatinine <200 μmol/L) | Rise in ANCA during treatment | Lower cumulative CYC exposure |

ANCA = antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; CYC = cyclophosphamide; ENT = ear, nose and throat; GPA = granulomatosis with polyangiitis; PR3 = proteinase 3

The optimum use of rituximab for remission maintenance remains to be established. A strategy of fixed interval retreatment for up to 2 years appears to be better than retreatment based on other clinical relapse, return of peripheral B-cells or ANCA status.18 The MAINRITSAN (efficacy study of two treatments in the remission of vasculitis) trial reported that rituximab 500 mg given at days 0, 14 and at months 6, 12 and 18 was more effective in remission maintenance than azathioprine regimen.19 Hypogammaglobulinaemia has been observed after rituximab treatment and measurement of serum immunoglobulin levels prior to each course of rituximab and in those with recurrent infection is recommended.12

Treatment intent is now long term and, therefore, attention should be paid to the morbidity associated with treatment. All patients should be screened for cardiovascular disease and appropriate treatment given to reduce risk factors. Osteoporosis prevention, immunisation against pneumococcus (preferably before immunosuppression is begun) and annual influenza vaccination should be given. Patients need specific education about their condition and their treatment as they may find it difficult to obtain the necessary information.20 The increasing complexity of disease management means that a multidisciplinary approach is essential for optimal management and networks of interested clinicians need to be developed.

Prognosis

Patients with AAV are at risk of complications, both from their disease and its treatment.5 Mortality in the first year is mainly due to active vasculitis or infection, late mortality is due to infection, cardiovascular disease and malignancy; 5-year survival is around 75%. Morbidity accumulates with time because of the consequences of active disease and therapies. Around one-third of patients have five or more items of damage at a mean of 7 years post-diagnosis.5

Conclusions

The conditions that comprise AAV are challenging to diagnose but improved treatment regimens with the introduction of rituximab have improved the outlook for patients. These conditions need to be considered as chronic diseases and care needs to be organised into regional networks so that all patients benefit from access to appropriate and timely advice without necessarily having to travel to a specialist centre.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- 1.Davies DJ. Moran JE. Niall JF. Ryan GB. Segmental necrotising glomerulonephritis with antineutrophil antibody: possible arbovirus aetiology? Br Med J. 1982;285:606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6342.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennette JC. Falk RJ. Bacon PA, et al. Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1–11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilhorst M. van Passen Tervaert P. Limburg Renal Registry JW. Proteinase 3-ANCA vasculitis versus myeloperoxidase vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2314–27. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014090903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts RA. Mahr A. Mohammad AJ, et al. Classification, epidemiology and clinical subgrouping of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(Suppl 1):i14–22. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robson J. Doll H. Suppiah R, et al. Damage in the anca-associated vasculitides: long-term data from the European vasculitis study group (EUVAS) therapeutic trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:177–84. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukhtyar C. Lee R. Brown D, et al. Modification and validation of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (version 3) Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1827–32. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.101279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh JH. Kemna MJ. Cohen Tervaert JW. Kim WU. Can an increase in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody titer predict relapses in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis? Arthritis Rheum. 2016;68:1571–3. doi: 10.1002/art.39639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellmich B. Flossmann O. Gross WL, et al. EULAR recommendations for conducting clinical studies and/or clinical trials in systemic vasculitis: focus on anti‐neutrophil cytoplasm antibody‐associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:605–17. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.062711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jayne D. Rasmussen N. Andrassy K, et al. A randomized trial of maintenance therapy for vasculitis associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:36–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harper L. Morgan MD. Walsh M, et al. Pulse versus daily oral cyclophosphamide for induction of remission in ANCA-associated vasculitis: long-term follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:955–60. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ntatsaki E. Carruthers D. Chakravarty K, et al. BSR and BHPR guideline for the management of adults with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheumatology. 2014;53:2306–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yates M. Watts RA. Bajema IM, et al. EULAR/ERA-EDTA recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1583–94. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone JH. Merkel PA. Spiera R, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:221–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RB. Tervaert JW. Hauser T, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide in ANCA-associated renal vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:211–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unizony S. Villarreal M. Miloslavsky EM, et al. Clinical outcomes of treatment of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis based on ANCA type. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1166–9. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RB. Ferraro AJ. Chaudhry AN, et al. A multicenter survey of rituximab therapy for refractory antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2156–68. doi: 10.1002/art.24637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Groot K. Rasmussen N. Bacon PA, et al. Randomized trial of cyclophosphamide versus methotrexate for induction of remission in early systemic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2461–9. doi: 10.1002/art.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith RM. Jones RB. Guerry MJ, et al. Rituximab for remission maintenance in relapsing antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:3760–9. doi: 10.1002/art.34583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guillevin L. Pagnoux C. Karras A, et al. Rituximab versus azathioprine for maintenance in ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1771–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mooney J. Spalding N. Poland F, et al. The informational needs of patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis-development of an informational needs questionnaire. Rheumatology. 2014;53:1414–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]