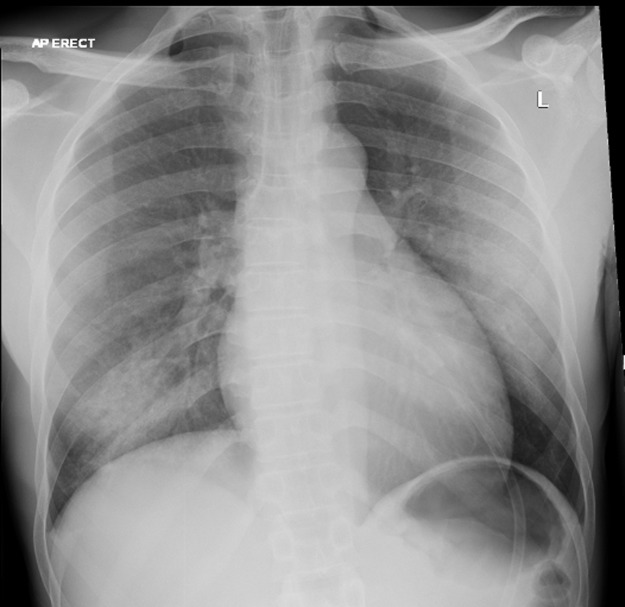

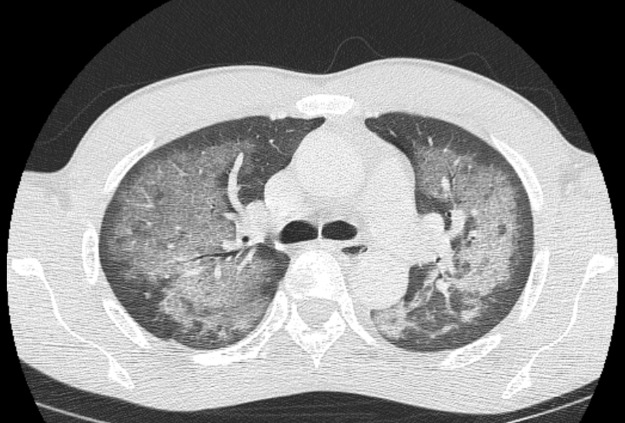

A previously well 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 48-hour history of worsening shortness of breath, dry cough, chest pain and fevers. He had no haemoptysis and reported no recent travel abroad. He had ordinarily smoked crack cocaine for the past 20 years although, in the 3 days preceding presentation to hospital, he had increased his cocaine use considerably. Peripheral blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 90% on room air and he was notably tachypnoeic. On examination, he exhibited no finger clubbing, peripheral stigmata of endocarditis or cervical lymphadenopathy. Bibasal crepitations were audible on praecordial auscultation. Blood panels showed mild neutrophilia of 10.19×109/L, normal eosinophil count, normal C-reactive protein and normocytic anaemia (haemoglobin 112 g/L). Haematinics were within normal limits and he was negative for HIV. Plain chest radiography (Fig 1) showed bilateral upper and mid-zone opacification with right lower zone and left mid-zone consolidation, but no effusions or collapse. Computerised tomography with contrast (Fig 2) demonstrated extensive bilateral ground-glass opacities in an alveolar distribution, with air bronchograms throughout. These changes spared the peripheral lung parenchyma. No mediastinal or axillary lymphadenopathy was in evidence. The patient was initially started on empirical antibiotics to cover the possibility of atypical pneumonia. In view of the above findings, a diagnosis of acute alveolitis secondary to crack cocaine inhalation was made. Although unlikely in our case, the main differentials were acute respiratory distress syndrome, heart failure and pneumonia, including Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and acute eosinophilic pneumonia.

Fig 1.

Chest radiograph on admission, showing bilateral upper and mid-zone opacification with right lower zone and left mid-zone consolidation.

Fig 2.

Computerised tomography chest with contrast demonstrating, at the level of the carina, extensive bilateral ground-glass opacities with air bronchograms in an alveolar distribution sparing the periphery.

At follow-up 1 week later, and having abstained from cocaine smoking in the interim, the patient reported a dramatic improvement in his breathing, back to premorbid baseline. SpO2 was 99% on air. A repeat chest radiograph (Fig 3) illustrated complete resolution.

Fig 3.

A repeat chest radiograph 7 days following presentation illustrated complete radiological resolution.

Clinico-radiological correlation – in particular, the temporal relationship between cocaine use and symptom onset – clinched the diagnosis as ‘crack lung’, otherwise called cocaine-induced lung injury, a syndrome of diffuse alveolar damage and haemorrhagic alveolitis occurring within 48 hours of smoking crack cocaine.1 The correct diagnosis was reached by paying close attention to the drug history and confirmed retrospectively by observing complete symptomatic and radiological resolution upon smoking cessation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions

AG drafted the manuscript, KS reviewed the patient in clinic, RJJ and IM advised on the case and critically appraised the draft manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the clinical details and images in this article.

Reference

- 1.Zimmerman JL. Cocaine intoxication. Crit Care Clin. 2012;28:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]