Abstract

Two powerful reflexes controlling cardiovascular function during exercise are the muscle metaboreflex and arterial baroreflex. In heart failure (HF), the strength and mechanisms of these reflexes are altered. Muscle metaboreflex activation (MMA) in normal subjects increases mean arterial pressure (MAP) primarily via increases in cardiac output (CO), whereas in HF the mechanism shifts to peripheral vasoconstriction. Baroreceptor unloading increases MAP via peripheral vasoconstriction, and this pressor response is blunted in HF. Baroreceptor unloading during MMA in normal animals elicits an enormous pressor response via combined increases in CO and peripheral vasoconstriction. The mode of interaction between these reflexes is intimately dependent on the parameter (e.g., MAP and CO) being investigated. The interaction between the two reflexes when activated simultaneously during dynamic exercise in HF is unknown. We activated the muscle metaboreflex in chronically instrumented dogs during mild exercise (via graded reductions in hindlimb blood flow) followed by baroreceptor unloading [via bilateral carotid occlusion (BCO)] before and after induction of HF. We hypothesized that BCO during MMA in HF would cause a smaller increase in MAP and a larger vasoconstriction of ischemic hindlimb vasculature, which would attenuate the restoration of blood flow to ischemic muscle observed in normal dogs. We observed that BCO during MMA in HF increases MAP by substantial vasoconstriction of all vascular beds, including ischemic active muscle, and that all cardiovascular responses, except ventricular function, exhibit occlusive interaction. We conclude that vasoconstriction of ischemic active skeletal muscle in response to baroreceptor unloading during MMA attenuates restoration of hindlimb blood flow.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY We found that baroreceptor unloading during the muscle metaboreflex in heart failure results in occlusive interaction (except for ventricular function) with significant vasoconstriction of all vascular beds. In addition, restoration of blood flow to ischemic active muscle, via preferentially larger vasoconstriction of nonischemic beds, is significantly attenuated in heart failure.

Keywords: exercise pressor reflex, ischemic skeletal muscle, muscle blood flow, sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction

INTRODUCTION

Stimulation of skeletal muscle afferents by metabolites, such as H+, lactic acid, and diprotonated phosphate, elicits a large pressor response, termed the muscle metaboreflex (1, 4, 14, 30, 35). Muscle metaboreflex activation (MMA) during dynamic exercise increases mean arterial pressure (MAP). In normal subjects, this pressor response occurs predominantly via large increases in cardiac output (CO) with little net peripheral vasoconstriction (3, 8, 9, 11, 32, 34, 36). CO increases due to increased heart rate (HR) and stroke volume being sustained via increased ventricular contractility, central blood volume mobilization, and right atrial pressure (7, 13, 21, 31, 32, 42, 46). Another powerful blood pressure-regulating reflex operating during exercise is the arterial baroreflex, a short-term negative-feedback reflex that maintains arterial pressure primarily by modulating peripheral vascular tone (5, 24, 37, 38, 43). Thus, the muscle metaboreflex and arterial baroreflex regulate arterial pressure via two distinct mechanisms: the muscle metaboreflex has stronger control over cardiac sympathetic activity and increases MAP by increasing CO, whereas the arterial baroreflex has stronger control over peripheral sympathetic activity and increases MAP primarily through peripheral vasoconstriction. These reflexes also interact with each other, which affects the mechanisms. In normal subjects, the arterial baroreflex buffers the muscle metaboreflex by ~50%. After sinoaortic baroreceptor denervation (SAD), the metaboreflex pressor response was about twofold greater and occurred via an increase in CO in combination with substantial peripheral vasoconstriction (20, 33). Thus, SAD revealed the ability of the muscle metaboreflex to elicit robust peripheral vasoconstriction, and these observations further support the primacy of baroreflex control over the peripheral vasculature versus the heart, inasmuch as the CO component of the muscle metaboreflex was actually somewhat smaller after SAD. In addition, central command, a feedforward mechanism activated during exercise, can also modulate the arterial baroreflex independently and in conjunction with the muscle metaboreflex, although further studies are required to address how this interaction occurs (10, 22, 25, 28).

In heart failure (HF), the strength and mechanisms of the muscle metaboreflex and arterial baroreflex are altered (11, 18, 19, 23, 39). Impaired baroreflex sensitivity in HF results in a smaller increase in MAP in response to carotid hypotension at rest (27, 44, 45) and during exercise (18, 19). With limited CO reserve in HF, the muscle metaboreflex-mediated pressor response occurs primarily via peripheral vasoconstriction (2, 6, 7, 11). This shift in metaboreflex mechanisms to peripheral vasoconstriction likely reflects the reduced ability of the baroreflex to buffer the metaboreflex. SAD in HF resulted in metaboreflex mechanisms similar to those in baroreceptor-intact HF animals, although peripheral vasoconstriction occurs to a somewhat greater extent after SAD (19).

In normal animals, baroreceptor unloading during MMA [induced by graded reductions in hindlimb blood flow (HLBF)] showed diverse interactions between different variables: MAP, ventricular function, and total vascular conductance of the nonischemic beds [nonischemic vascular conductance (NIVC)] were additive, CO and renal vascular conductance (RVC) were occlusive, and HR responses were facilitative. Moreover, a larger preferential vasoconstriction of the nonischemic vascular beds redirected blood flow to the ischemic muscle, increasing HLBF. In the present study, we investigated whether the interaction between these two powerful blood pressure-raising reflexes is altered in HF. We further studied the effect of combined metaboreflex- and baroreflex-mediated sympathoexcitation on ischemic active muscle in HF and whether blood flow to the ischemic muscle is restored.

METHODS

Experimental Animals

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wayne State University and complied with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Five adult mongrel dogs (20–25 kg; 1 male dog and 4 female dogs) were selected for the study. Animals were acclimatized to the laboratory surroundings and exercised voluntarily during experimentation; no negative reinforcement techniques were used.

Surgical Procedures

The surgical procedures and medications have been previously described elsewhere (16). Briefly, a 20-mm flow transducer was placed around the aortic root to measure CO. A telemetry pressure transmitter was tethered subcutaneously, and its tip was inserted into the left ventricle to measure left ventricular pressure (LVP). Three to four stainless steel pacing wires (0-Flexon) were secured to the right ventricular free wall. In a second procedure, through a retroperitoneal approach, blood flow transducers were placed around the terminal aorta and left renal artery to measure HLBF and renal blood flow (RBF), respectively. Two hydraulic occluders were placed around the terminal aorta distal to the flow probe to reduce HLBF. Arterial catheters were placed to measure systemic arterial pressure and femoral arterial pressure (FAP). In a final procedure, hydraulic occluders were placed around common carotid arteries ~6 cm below the carotid sinuses to achieve bilateral carotid occlusion (BCO). Animals recovered for ≥2 wk after each surgery.

Data Acquisition

Before each experiment, animals acclimated to the laboratory for ~10–20 min; they were then directed onto the treadmill. The arterial catheters were aspirated, flushed, and connected to pressure transducers (Transpac IV, ICU Medical), the flow probe cables were connected to flowmeters (model TS420, Transonic Systems), and the left ventricular telemetry implant was turned on. All hemodynamic variables were monitored as real-time waveforms by a LabScribe2 data-acquisition system (iWorx) and recorded for offline analysis.

Experimental Procedures

Three different experimental protocols were performed: BCO at rest, BCO during exercise, and BCO during MMA.

BCO at rest.

Steady-state data at rest were collected while the animal stood still on the treadmill. The carotid occluders were then inflated for 2 min to achieve BCO.

BCO during exercise.

Resting steady-state data were collected, and treadmill speed was gradually increased to 3.2 km/h at 0% grade (mild exercise). Animals exercised until all hemodynamic data were stable (~5–10 min), followed by BCO for 2 min during exercise at the same workload.

BCO during MMA.

After the collection of steady-state data at rest and during mild exercise, HLBF was gradually reduced to ~40% of free-flow exercising levels (via partial inflations of the terminal aortic occluders) to activate the muscle metaboreflex. Once steady state for MMA was achieved and data were recorded, BCO was applied for 2 min during metaboreflex activation. The large increase in MAP with BCO during metaboreflex activation causes an increase in HLBF, which in turn alters the metaboreflex stimulus. Thus, HLBF was kept constant by increasing the occluder resistance.

After completion of experiments in normal animals, rapid ventricular pacing at a rate of 220–240 beats/min was used to induce HF in the same animals. Pacing was maintained for 34 ± 3 days until classic symptoms of HF, which included depressed ventricular function and CO and tachycardia, ensued. All three experimental protocols were repeated after the induction of HF. Not all three experimental protocols were performed on the same day for all animals. When BCO at rest and BCO during exercise were performed on the same day, animals rested for ≥15–20 min between the protocols to allow all hemodynamic variables to return to baseline. On a given day, no experimental protocols were performed after the BCO during MMA.

Data Analysis

MAP, FAP, CO, HLBF, RBF, HR (triggered from the CO signal), and LVP were continuously recorded during each experiment. Other hemodynamic parameters were calculated during offline data analysis [e.g., maximal rate of rise and fall in LVP (dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, respectively), total vascular conductance (TVC), RVC, hindlimb vascular conductance (HVC), and conductance of all vascular beds except the hindlimbs (NIVC)]. Because of technical difficulties, dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin were calculated in only four animals. Vascular conductance for different vascular beds was calculated as follows: TVC = CO/MAP, RVC = RBF/MAP, HVC = HLBF/FAP, and NIVC = (CO – HLBF)/MAP. One-minute averages of all variables were taken during steady states at rest and during mild exercise, during BCO at rest and during mild exercise, during MMA, and during BCO and metaboreflex activation. Mean values were averaged across all animals to obtain the sample mean of the study. The pressor response observed with metaboreflex activation in our experiments is a combination of a reflex increase in MAP due to metaboreflex activation (MAPactive) and the passive increase in MAP due solely to the mechanical effect of terminal aortic occluders (MAPpassive). MAPpassive was calculated as COEx/(NIVCEx + HVCobserved), where the subscript Ex indicates free-flow exercise level (3, 46). MAPactive was calculated by subtraction of the passive increase in MAP from the observed MAP values at maximal metaboreflex activation. During baroreceptor unloading combined with metaboreflex activation, we kept HLBF constant by increasing the occluder resistance. We calculated the HLBF if there was no increase in occluder resistance (predicted HLBF) as (MAP during BCO)/(hindlimb vascular resistance during BCO + occluder resistance during metaboreflex activation), where hindlimb resistance was calculated as FAP/HLBF and occluder resistance during the metaboreflex was calculated as (MAP – FAP)/HLBF, all observed during metaboreflex activation.

Statistical Analysis

All hemodynamic data are reported as means ± SE. An α-level of P < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Average responses for each animal were analyzed with Systat 11.0. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used to compare hemodynamic data for effect of condition (normal vs. HF) and/or effect of settings (effect of baroreflex unloading, metaboreflex activation, and combination of both). In the event of a significant time-condition interaction, a C-matrix test for simple effects was performed.

RESULTS

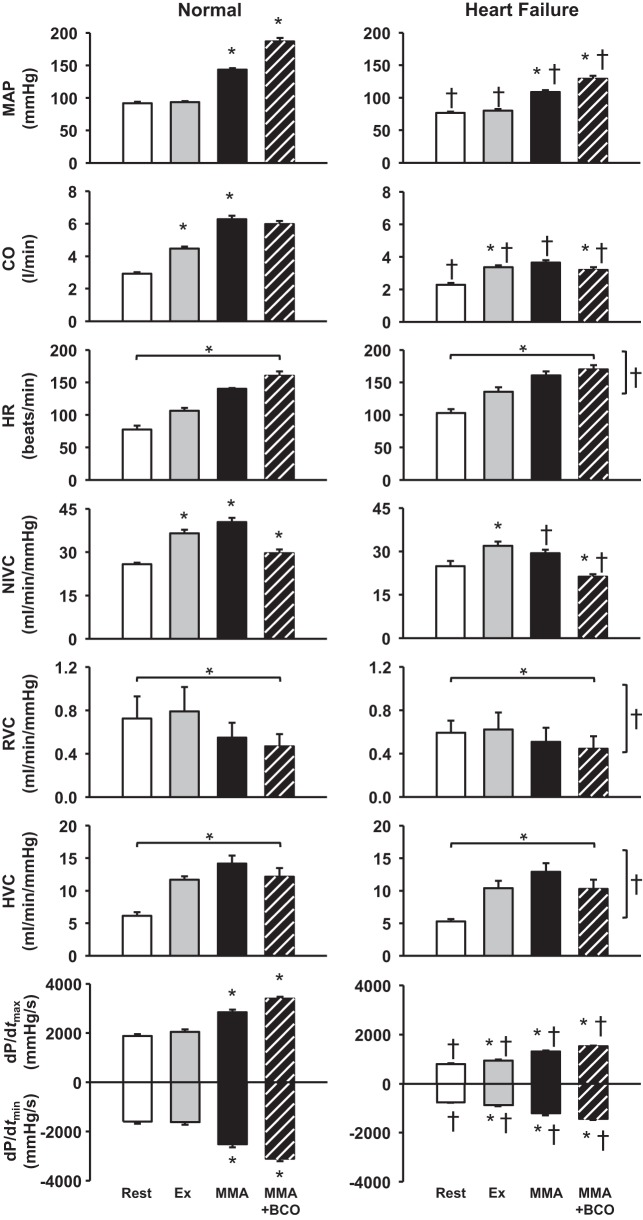

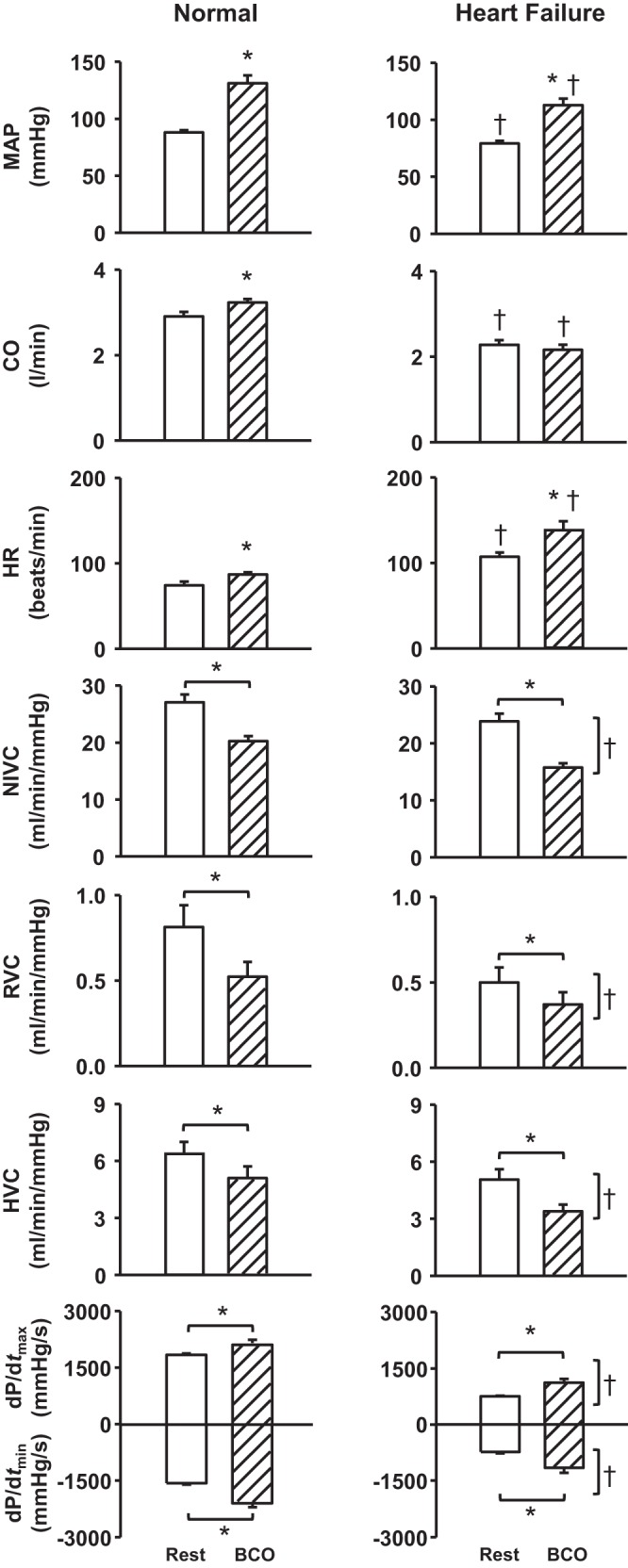

Figure 1 shows the average hemodynamic responses evoked by BCO at rest before and after induction of HF. Carotid baroreceptor unloading at rest caused a significant increase in MAP (∆: 39 ± 4 mmHg), CO, and HR. After the induction of HF, resting MAP (normal: 87 ± 3 mmHg, HF: 77 ± 3 mmHg) and CO (normal: 3.0 ± 0.1 l/min, HF: 2.3 ± 0.1 l/min) were significantly lower and resting HR (normal: 75 ± 4 beats/min, HF: 112 ± 7 beats/min) was significantly higher. BCO at rest elicited large increases in MAP (∆: 31 ± 5 mmHg) and HR in HF; however, the magnitude of the pressor response was significantly lower and the HR response was markedly higher than in normal animals. The small, but significant, increase in CO in normal animals was abolished in HF. For NIVC, RVC, HVC, dP/dtmax, and dP/dtmin, there was a significant effect of BCO and HF.

Fig. 1.

Average values for cardiovascular variables at rest and during bilateral carotid occlusion (BCO) at rest in normal animals and after the induction of heart failure. *P < 0.05 vs. rest; †P < 0.05 vs. normal. Horizontal brackets indicate a significant effect of settings (baroreceptor unloading); vertical brackets reflect a significant effect of condition (normal vs. heart failure). MAP, mean arterial pressure; CO, cardiac output; HR, heart rate; NIVC, nonischemic vascular conductance; RVC, renal vascular conductance; HVC, hindlimb vascular conductance; dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, maximal rates of rise and fall, respectively, in left ventricular pressure.

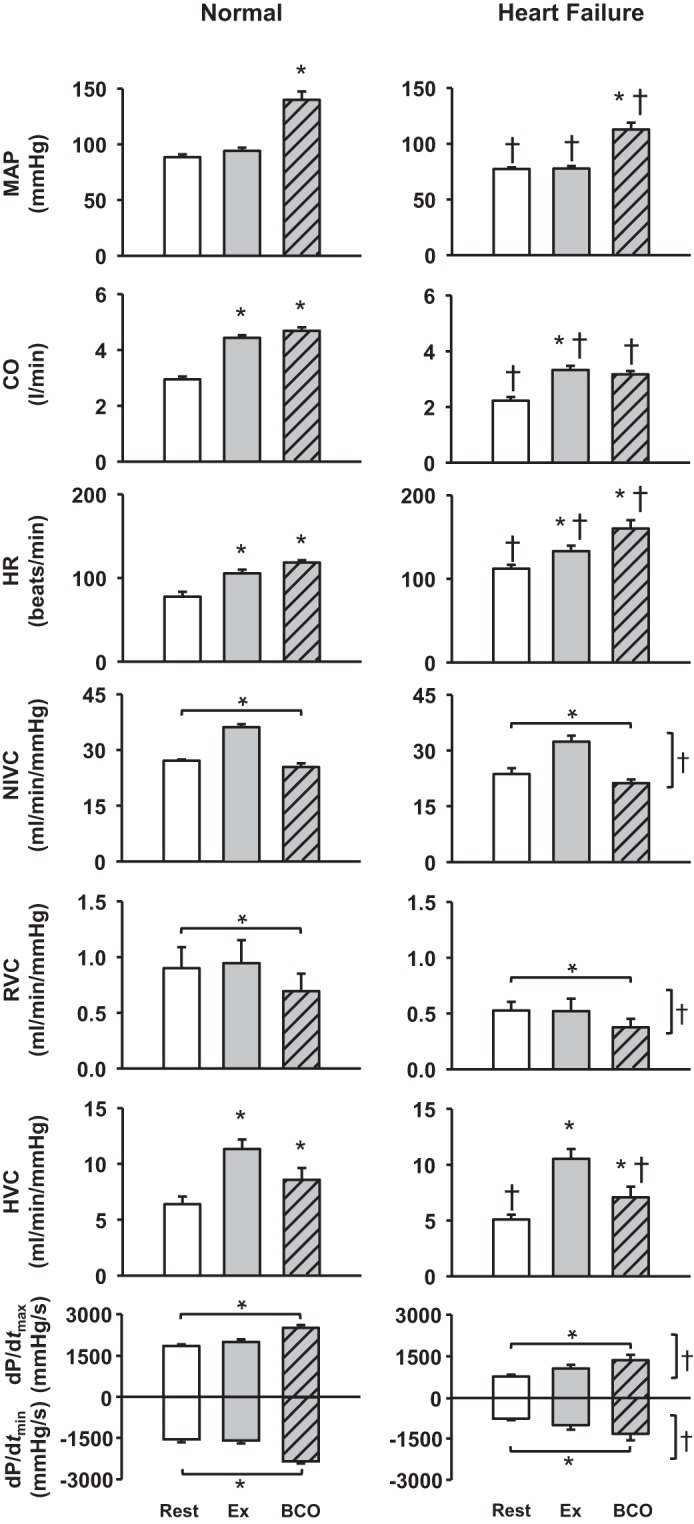

Average cardiovascular responses to BCO during exercise before and after induction of HF are shown in Fig. 2. From rest to mild exercise, there was a moderate increase in CO, HR, NIVC, and HVC. BCO during mild exercise resulted in large increases in MAP, CO, and HR and a decrease in HVC. In HF, responses to mild exercise were similar to those in normal animals but with attenuated resting and exercise levels of MAP, CO, and HVC. With BCO during exercise in HF, there was a significant increase in MAP (exercise: 78 ± 3 mmHg, BCO during exercise: 110 ± 7 mmHg) and HR (exercise: 139 ± 7 beats/min, BCO during exercise: 162 ± 8 beats/min), with no change in CO and a decrease in HVC. There was a significant effect of settings and HF on NIVC, RVC, dP/dtmax, and dP/dtmin responses.

Fig. 2.

Average hemodynamic data at rest, during mild exercise (Ex), and bilateral carotid occlusion (BCO) during exercise in normal animals and after the induction of heart failure. *P < 0.05 vs. previous setting; †P < 0.05 vs. normal. Horizontal brackets reflect a significant effect of settings; vertical brackets reflect a significant effect of heart failure. MAP, mean arterial pressure; CO, cardiac output; HR, heart rate; NIVC, nonischemic vascular conductance; RVC, renal vascular conductance; HVC, hindlimb vascular conductance; dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, maximal rates of rise and fall, respectively, in left ventricular pressure.

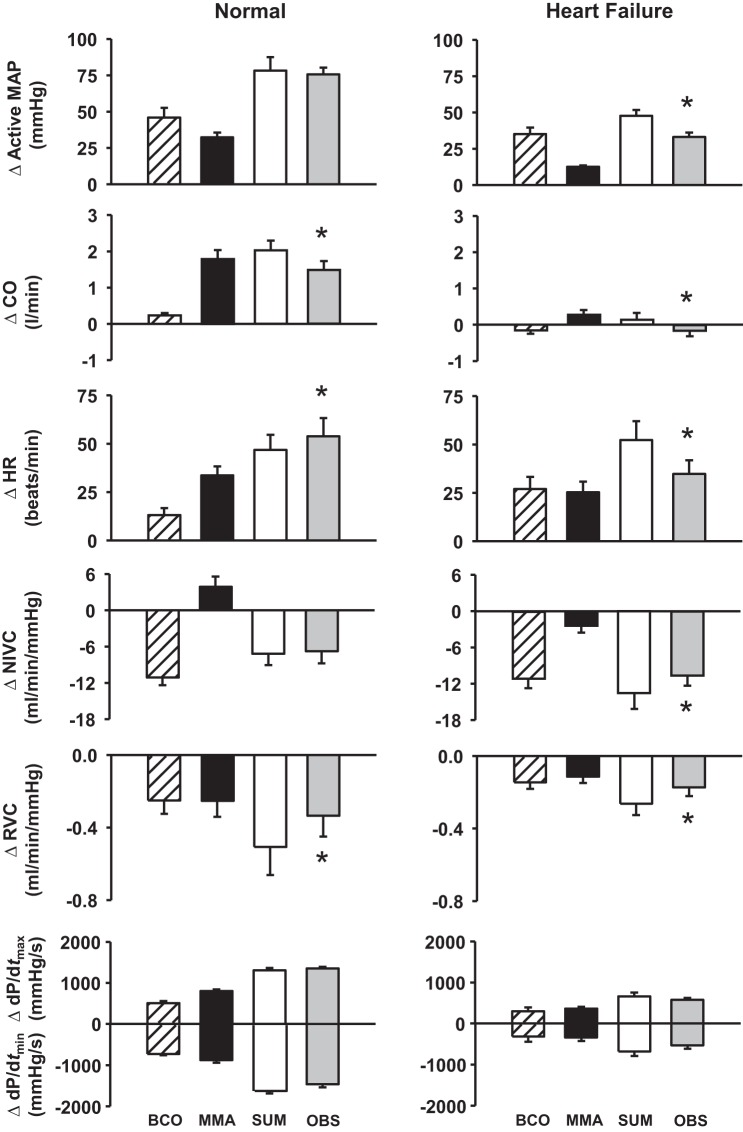

Figure 3 shows average hemodynamic changes in response to BCO during MMA before and after induction of HF. MMA during mild exercise elicits significant increases in MAP, CO, NIVC, dP/dtmax, and dP/dtmin. With BCO during metaboreflex activation, there are further large increases in MAP and ventricular dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, with significant decreases in CO and NIVC. There was a significant effect of settings on HR, RVC, and HVC in normal animals. After the induction of HF, MMA caused attenuated increases in MAP (∆: 49 ± 1 mmHg in normal vs. 28 ± 2 mmHg after induction of HF) and ventricular function compared with normal animals. The metaboreflex-induced CO increase in normal animals was abolished after the induction of HF (∆: 1.7 ± 0.2 l/min in normal vs. 0.3 ± 0.1 l/min in HF), and there was vasoconstriction in the nonischemic vasculature. BCO during metaboreflex activation caused a large pressor response, vasoconstriction of nonischemic vascular beds, and improvement in ventricular function; however, these responses were markedly lower than those observed before the induction of HF. There was a significant effect of HF and settings on HR, RVC, and HVC responses.

Fig. 3.

Average hemodynamic data at rest, during mild exercise (Ex), muscle metaboreflex activation (MMA), and bilateral carotid occlusion (BCO) during MMA in normal animals and after the induction of heart failure. *P < 0.05 vs. previous setting; †P < 0.05 vs. normal. Horizontal brackets reflect a significant effect of settings; vertical brackets reflect a significant effect of heart failure. MAP, mean arterial pressure; CO, cardiac output; HR, heart rate; NIVC, nonischemic vascular conductance; RVC, renal vascular conductance; HVC, hindlimb vascular conductance; dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, maximal rates of rise and fall, respectively, in left ventricular pressure.

To investigate the mode of interaction between the arterial baroreflex and muscle metaboreflex (i.e., additive, facilitative, or occlusive interaction), the responses during baroreceptor unloading combined with metaboreflex activation were compared with the arithmetic sum of metaboreflex-induced and BCO-induced responses during exercise. Additive interactions occur when the response during BCO + metaboreflex equals the arithmetic sum of the reflex responses when performed individually, facilitative interactions occur when the response during BCO + metaboreflex is larger than the arithmetic sum of responses during individual reflex activation, and occlusive interactions occur when the response during BCO + metaboreflex is smaller than the sum of individual reflex responses. Figure 4 shows average cardiovascular responses when the arterial baroreflex and muscle metaboreflex were activated separately and concurrently. To investigate whether the interaction between the two reflexes is altered in HF, the responses during baroreceptor unloading and metaboreflex activation in HF were compared with the arithmetic sum of metaboreflex-induced and BCO-induced responses during exercise in HF. In healthy animals, MAP, NIVC, and ventricular function responses displayed additive interaction, HR responses exhibited facilitative interaction, and CO and RVC responses demonstrated occlusive interaction. After the induction of HF, all cardiovascular parameters exhibited occlusive interaction, with the exception of ventricular function responses, which displayed additive interaction.

Fig. 4.

Absolute changes (Δ) in cardiovascular responses evoked by bilateral carotid occlusion (BCO) during exercise and muscle metaboreflex activation (MMA), calculated MMA + BCO during exercise (SUM), and observed effect of MMA + BCO (OBS). *P < 0.05 vs. SUM. MAP, mean arterial pressure; CO, cardiac output; HR, heart rate; NIVC, nonischemic vascular conductance; RVC, renal vascular conductance; dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, maximal rates of rise and fall, respectively, in left ventricular pressure

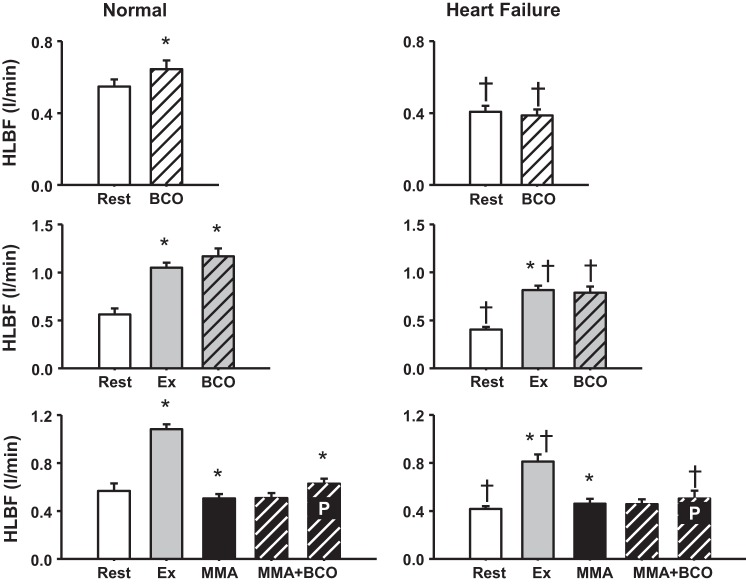

Figure 5 shows HLBF responses during BCO at rest, during mild exercise, and during MMA in normal animals and in the same animals after the induction of HF. In normal animals, there was a significant increase in HLBF with BCO at rest and during exercise that was abolished after the induction of HF (normal: 12 ± 4% increase vs. HF: 1 ± 0% increase in HLBF from exercise to BCO during exercise). BCO during MMA in normal animals causes hindlimb vasoconstriction; however, the greater vasoconstriction in other vascular beds redirects blood flow to the ischemic hindlimb vasculature. This significant increase in HLBF (predicted) during BCO combined with metaboreflex activation was substantially attenuated in HF (∆: 0.14 ± 0.02 l/min in normal and 0.07 ± 0.03 l/min in HF).

Fig. 5.

Top: average hindlimb blood flow (HLBF) at rest and during bilateral carotid occlusion (BCO) at rest. Middle: average HLBF at rest, during mild exercise (Ex), and BCO during mild exercise. Bottom: average HLBF at rest, during mild exercise (Ex), muscle metaboreflex activation (MMA), and MMA + BCO. Bars inscribed with P indicate predicted HLBF during MMA + BCO. *P < 0.05 vs. previous setting; †P < 0.05 vs. normal.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to investigate the interaction between the muscle metaboreflex and arterial baroreflex during sympathoexcitation via baroreceptor unloading during metaboreflex activation in HF. We found that BCO during metaboreflex activation in HF induces a large pressor response that occurs via peripheral vasoconstriction of all vascular beds, including even the ischemic active skeletal muscle. Unlike in normal animals, there is no preferential vasoconstriction of the nonischemic vasculature during concurrent BCO and metaboreflex activation, thereby preventing the redistribution of CO toward the ischemic beds. As such, the restoration of blood flow to the ischemic active skeletal muscle is significantly attenuated in HF. Furthermore, during baroreceptor unloading combined with metaboreflex activation after the induction of HF, all the hemodynamic responses except ventricular function converted to occlusive interaction. Although dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin responses were significantly attenuated in HF, they maintained an additive interaction upon baroreceptor unloading during metaboreflex activation. Therefore, the interaction between the muscle metaboreflex and arterial baroreflex in HF is predominantly occlusive, and the responses are significantly depressed compared with those of normal animals.

We previously showed that the interaction between the arterial baroreflex and muscle metaboreflex in normal animals is dependent on the hemodynamic parameter being investigated (15). Our results agree with the previous study (15), as MAP, NIVC, and ventricular function responses during BCO combined with MMA exhibited additive interaction, CO and RVC responses were occlusive, and HR responses showed facilitative interaction. In addition, the vasoconstriction within nonischemic vascular beds was greater during combined MMA and baroreceptor unloading than in the ischemic muscle, resulting in redistribution of CO toward the ischemic beds. After induction of HF, baroreceptor unloading during MMA induced a pressor response via peripheral vasoconstriction, and this increase in MAP was significantly attenuated in HF compared with normal animals. These results are in agreement with previous studies showing that metaboreflex activation during mild exercise in HF results in a smaller, but substantial, increase in MAP (11, 12). However, metaboreflex-mediated responses during higher exercise intensities are exaggerated in HF (11, 12). In addition, the restoration of blood flow to the ischemic muscle during combined metaboreflex activation and BCO in normal animals was significantly attenuated after induction of HF.

The mechanisms for different interactions for the hemodynamic responses are unclear. In healthy animals, the pressor response during metaboreflex activation results from an increase in CO, whereas additional increases in MAP during combined BCO and MMA occur primarily via peripheral vasoconstriction, leading to additive interaction. Since CO is already significantly elevated during MMA, large increases in afterload during simultaneous BCO and metaboreflex activation likely limit a further increase in CO, potentially resulting in occlusive interaction. HR in normal animals increases significantly during the metaboreflex and increases further with combined baroreceptor unloading and metaboreflex activation. However, after the induction of HF, the mechanisms change and the interactions are occlusive. This may be due to impaired baroreflex function in HF (18, 19, 27, 45). Metaboreflex pressor responses in HF occur primarily due to peripheral vasoconstriction, as increases in CO are limited. With BCO during metaboreflex, there is further peripheral vasoconstriction, but the likely increased afterload sensitivity in HF contributes to the lack of an increase in CO, which potentially contributes to the occlusive interaction. Resting HR is significantly elevated in HF and increases significantly during metaboreflex and combined baroreceptor unloading during metaboreflex, reaching values of ~180 beats/min. Chronotropic incompetence in HF may contribute to impaired increases in HR.

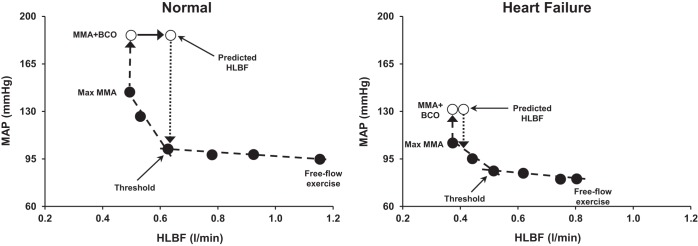

Regulation of Skeletal Muscle Blood Flow

Baroreceptor unloading during metaboreflex activation in healthy subjects causes vasoconstriction in all vascular beds, including the ischemic hindlimb vasculature. However, there is a large preferential vasoconstriction of the nonischemic vasculature, which redirects CO to the ischemic active muscle, increasing HLBF. Thus, during these experiments, we needed to increase the occluder resistance to maintain HLBF constant during the BCO. Otherwise, the pressor response and the preferential vasoconstriction in the nonischemic vasculature would have substantially increased HLBF and, thereby, decreased the stimulus for the muscle metaboreflex. Thus, when both reflexes are activated, the baroreflex acts to protect blood flow to the ischemic muscle by eliciting greater vasoconstriction in the nonischemic beds. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 6, left, when BCO was superimposed on MMA, the increase in MAP and a larger preferential vasoconstriction of nonischemic beds would have increased blood flow to the ischemic muscle enough to nearly entirely remove the metaboreflex stimulus. Inasmuch as a large fraction of nonischemic vascular conductance during exercise is active skeletal muscle (20), vasoconstriction in the nonischemic active skeletal muscle likely occurred. Previous studies from our laboratory show that the baroreflex is capable of eliciting substantial vasoconstriction in active skeletal muscle during dynamic exercise (5, 26).

Fig. 6.

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) and hindlimb blood flow (HLBF) during free-flow mild exercise and during graded reductions in HLBF eliciting muscle metaboreflex activation (MMA; ●) followed by bilateral carotid occlusion (BCO) during MMA (○) in a control experiment (normal) and after induction of heart failure in 1 animal.

After the induction of HF, BCO during metaboreflex activation caused an increase in MAP via peripheral vasoconstriction, which included vasoconstriction within the ischemic skeletal muscle. Unlike the situation in normal animals, there is very little restoration of HLBF with baroreceptor unloading during metaboreflex activation in HF. Figure 6, right, shows that the predicted increase in HLBF with BCO during MMA in HF is very small and does little to relieve the muscle metaboreflex stimulus. In normal animals, the attenuated vasoconstriction of ischemic active muscle vs. nonischemic muscle could be a result of functional sympatholysis, attenuated sympathetic vasoconstriction of active muscle due to accumulation of metabolites in the muscle (29, 40). Since functional sympatholysis is impaired in HF (41), the unopposed sympathetic vasoconstriction in the ischemic vascular bed prevents any significant increase in HLBF. Thus, in HF, the protection of blood flow to the ischemic muscle during BCO combined with metaboreflex activation is markedly attenuated. This can further exacerbate an already precarious situation wherein further vasoconstriction of ischemic skeletal muscle occurs, which could drive further sympathoactivation.

Limitations

In this study, we examined only the effects of carotid hypotension. The aortic baroreceptors were intact during the experiments, and their activation by the large increase in MAP during metaboreflex activation or baroreceptor unloading would send opposing afferent information to the brain stem. If the afferent signals from the aortic baroreceptors were removed, we would have seen even more profound changes in the hemodynamic variables during our control experiments. Also, the muscle metaboreflex was activated by reducing HLBF, which was held constant until all cardiovascular parameters reached steady state. This reduction in flow could cause fatigue, which may affect these responses during metaboreflex activation.

Perspectives and Significance

In normal animals, the arterial baroreflex buffers about one-half of the metaboreflex-induced pressor response by attenuating peripheral vasoconstriction (20, 33). In HF, mechanisms of MMA switch from a CO-mediated to a peripheral vasoconstriction-mediated pressor response (11, 19). Impaired baroreflex buffering of the metaboreflex in HF would markedly increase sympathetic vasoconstriction of all vascular beds, especially to the ischemic active muscle. Vasoconstriction of the ischemic muscle may further activate the muscle metaboreflex. We previously showed that, in HF, MMA itself causes vasoconstriction in the ischemic muscle, thereby causing a positive-feedback amplification of sympathetic nerve activity, which generates progressively greater peripheral vasoconstriction (17). This “vicious cycle” scenario may contribute importantly to the greatly elevated levels of sympathetic activity during exercise in patients with HF and may significantly contribute to the hallmark symptoms of exercise intolerance in these patients.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-55473 and HL-126706.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.K. and D.S.O’L. conceived and designed research; J.K., A.C.K., D.S., A.A., H.W.H., and D.S.O’L. performed experiments; J.K. and D.S.O’L. analyzed data; J.K., A.C.K., D.S., and D.S.O’L. interpreted results of experiments; J.K. prepared figures; J.K. and D.S.O’L. drafted manuscript; J.K., A.C.K., D.S., and D.S.O’L. edited and revised manuscript; J.K., A.C.K., D.S., A.A., H.W.H., and D.S.O’L. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jody Helme-Day and Audrey Nelson for expert technical assistance and animal care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam M, Smirk FH. Observations in man upon a blood pressure raising reflex arising from the voluntary muscles. J Physiol 89: 372–383, 1937. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1937.sp003485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann M, Venturelli M, Ives SJ, Morgan DE, Gmelch B, Witman MA, Jonathan Groot H, Walter Wray D, Stehlik J, Richardson RS. Group III/IV muscle afferents impair limb blood in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 174: 368–375, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augustyniak RA, Collins HL, Ansorge EJ, Rossi NF, O’Leary DS. Severe exercise alters the strength and mechanisms of the muscle metaboreflex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H1645–H1652, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boushel R, Madsen P, Nielsen HB, Quistorff B, Secher NH. Contribution of pH, diprotonated phosphate and potassium for the reflex increase in blood pressure during handgrip. Acta Physiol Scand 164: 269–275, 1998. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins HL, Augustyniak RA, Ansorge EJ, O’Leary DS. Carotid baroreflex pressor responses at rest and during exercise: cardiac output vs. regional vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H642–H648, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coutsos M, Sala-Mercado JA, Ichinose M, Li Z, Dawe EJ, O’Leary DS. Muscle metaboreflex-induced coronary vasoconstriction limits ventricular contractility during dynamic exercise in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H1029–H1037, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00879.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crisafulli A, Salis E, Tocco F, Melis F, Milia R, Pittau G, Caria MA, Solinas R, Meloni L, Pagliaro P, Concu A. Impaired central hemodynamic response and exaggerated vasoconstriction during muscle metaboreflex activation in heart failure patients. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2988–H2996, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00008.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crisafulli A, Scott AC, Wensel R, Davos CH, Francis DP, Pagliaro P, Coats AJS, Concu A, Piepoli MF. Muscle metaboreflex-induced increases in stroke volume. Med Sci Sports Exerc 35: 221–228, 2003. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000048639.02548.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crisafulli A, Piras F, Filippi M, Piredda C, Chiappori P, Melis F, Milia R, Tocco F, Concu A. Role of heart rate and stroke volume during muscle metaboreflex-induced cardiac output increase: differences between activation during and after exercise. J Physiol Sci 61: 385–394, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s12576-011-0163-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallagher KM, Fadel PJ, Smith SA, Strømstad M, Ide K, Secher NH, Raven PB. The interaction of central command and the exercise pressor reflex in mediating baroreflex resetting during exercise in humans. Exp Physiol 91: 79–87, 2006. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond RL, Augustyniak RA, Rossi NF, Churchill PC, Lapanowski K, O’Leary DS. Heart failure alters the strength and mechanisms of the muscle metaboreflex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H818–H828, 2000. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.3.H818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammond RL, Augustyniak RA, Rossi NF, Lapanowski K, Dunbar JC, O’Leary DS. Alteration of humoral and peripheral vascular responses during graded exercise in heart failure. J Appl Physiol 90: 55–61, 2001. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ichinose MJ, Sala-Mercado JA, Coutsos M, Li Z, Ichinose TK, Dawe E, O’Leary DS. Modulation of cardiac output alters the mechanisms of the muscle metaboreflex pressor response. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H245–H250, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00909.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman MP, Rybicki KJ, Waldrop TG, Ordway GA. Effect of ischemia on responses of group III and IV afferents to contraction. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 57: 644–650, 1984. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.3.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur J, Alvarez A, Hanna HW, Krishnan AC, Senador D, Machado TM, Altamimi YH, Lovelace AT, Dombrowski MD, Spranger MD, O’Leary DS. Interaction between the muscle metaboreflex and the arterial baroreflex in control of arterial pressure and skeletal muscle blood flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311: H1268–H1276, 2016. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00501.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur J, Machado TM, Alvarez A, Krishnan AC, Hanna HW, Altamimi YH, Senador D, Spranger MD, O’Leary DS. Muscle metaboreflex activation during dynamic exercise vasoconstricts ischemic active skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H2145–H2151, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00679.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur J, Senador D, Krishnan AC, Hanna HW, Alvarez A, Machado TM, O’Leary DS. Muscle metaboreflex-induced vasoconstriction in the ischemic active muscle is exaggerated in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 314: H11–H18, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00375.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JK, Augustyniak RA, Sala-Mercado JA, Hammond RL, Ansorge EJ, Rossi NF, O’Leary DS. Heart failure alters the strength and mechanisms of arterial baroreflex pressor responses during dynamic exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1682–H1688, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00358.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JK, Sala-Mercado JA, Hammond RL, Rodriguez J, Scislo TJ, O’Leary DS. Attenuated arterial baroreflex buffering of muscle metaboreflex in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H2416–H2423, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00654.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JK, Sala-Mercado JA, Rodriguez J, Scislo TJ, O’Leary DS. Arterial baroreflex alters strength and mechanisms of muscle metaboreflex during dynamic exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H1374–H1380, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01040.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCloskey DI, Mitchell JH. Reflex cardiovascular and respiratory responses originating in exercising muscle. J Physiol 224: 173–186, 1972. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McIlveen SA, Hayes SG, Kaufman MP. Both central command and exercise pressor reflex reset carotid sinus baroreflex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H1454–H1463, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Notarius CF, Atchison DJ, Floras JS. Impact of heart failure and exercise capacity on sympathetic response to handgrip exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H969–H976, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogoh S, Fadel PJ, Nissen P, Jans Ø, Selmer C, Secher NH, Raven PB. Baroreflex-mediated changes in cardiac output and vascular conductance in response to alterations in carotid sinus pressure during exercise in humans. J Physiol 550: 317–324, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogoh S, Wasmund WL, Keller DM, O-Yurvati A, Gallagher KM, Mitchell JH, Raven PB. Role of central command in carotid baroreflex resetting in humans during static exercise. J Physiol 543: 349–364, 2002. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Leary DS, Rowell LB, Scher AM. Baroreflex-induced vasoconstriction in active skeletal muscle of conscious dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 260: H37–H41, 1991. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.1.H37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olivier NB, Stephenson RB. Characterization of baroreflex impairment in conscious dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Am J Physio Regul Integr Comp Physiol 265: R1132–R1140, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.5.R1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raven PB, Fadel PJ, Smith SA. The influence of central command on baroreflex resetting during exercise. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 30: 39–44, 2002. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remensnyder JP, Mitchell JH, Sarnoff SJ. Functional sympatholysis during muscular activity. Observations on influence of carotid sinus on oxygen uptake. Circ Res 11: 370–380, 1962. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.11.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rotto DM, Kaufman MP. Effect of metabolic products of muscular contraction on discharge of group III and IV afferents. J Appl Physiol 64: 2306–2313, 1988. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sala-Mercado JA, Hammond RL, Kim JK, Rossi NF, Stephenson LW, O’Leary DS. Muscle metaboreflex control of ventricular contractility during dynamic exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H751–H757, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00869.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheriff DD, Augustyniak RA, O’Leary DS. Muscle chemoreflex-induced increases in right atrial pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H767–H775, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheriff DD, O’Leary DS, Scher AM, Rowell LB. Baroreflex attenuates pressor response to graded muscle ischemia in exercising dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 258: H305–H310, 1990. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.2.H305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoemaker JK, Mattar L, Kerbeci P, Trotter S, Arbeille P, Hughson RL. WISE 2005: stroke volume changes contribute to the pressor response during ischemic handgrip exercise in women. J Appl Physiol 103: 228–233, 2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01334.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinoway LI, Wroblewski KJ, Prophet SA, Ettinger SM, Gray KS, Whisler SK, Miller G, Moore RL. Glycogen depletion-induced lactate reductions attenuate reflex responses in exercising humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 263: H1499–H1505, 1992. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.5.H1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spranger MD, Sala-Mercado JA, Coutsos M, Kaur J, Stayer D, Augustyniak RA, O’Leary DS. Role of cardiac output versus peripheral vasoconstriction in mediating muscle metaboreflex pressor responses: dynamic exercise versus postexercise muscle ischemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R657–R663, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00601.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephenson RB, Donald DE. Reflexes from isolated carotid sinuses of intact and vagotomized conscious dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 238: H815–H822, 1980. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.6.H815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephenson RB, Donald DE. Reversible vascular isolation of carotid sinuses in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 238: H809–H814, 1980. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.6.H809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sterns DA, Ettinger SM, Gray KS, Whisler SK, Mosher TJ, Smith MB, Sinoway LI. Skeletal muscle metaboreceptor exercise responses are attenuated in heart failure. Circulation 84: 2034–2039, 1991. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.84.5.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas GD, Segal SS. Neural control of muscle blood flow during exercise. J Appl Physiol 97: 731–738, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00076.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas GD, Zhang W, Victor RG. Impaired modulation of sympathetic vasoconstriction in contracting skeletal muscle of rats with chronic myocardial infarctions: role of oxidative stress. Circ Res 88: 816–823, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.089341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Victor RG, Seals DR. Reflex stimulation of sympathetic outflow during rhythmic exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H2017–H2024, 1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.6.H2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walgenbach SC, Donald DE. Inhibition by carotid baroreflex of exercise-induced increases in arterial pressure. Circ Res 52: 253–262, 1983. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.52.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang W, Chen JS, Zucker IH. Carotid sinus baroreceptor sensitivity in experimental heart failure. Circulation 81: 1959–1966, 1990. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.81.6.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson JR, Lanoce V, Frey MJ, Ferraro N. Arterial baroreceptor control of peripheral vascular resistance in experimental heart failure. Am Heart J 119: 1122–1130, 1990. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(05)80243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyss CR, Ardell JL, Scher AM, Rowell LB. Cardiovascular responses to graded reductions in hindlimb perfusion in exercising dogs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 245: H481–H486, 1983. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.3.H481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]