Short abstract

It has been 12 years after Porter and Teisberg published their landmark manuscript on “Redefining Health Care.” Apart from stressing the need for a fundamental change from fee-for-service to value or outcome-based financing and to a focus on reducing waste, they emphasized the need to work along patient pathways and in Integrated Practice Units to overcome function based and specialist group silos and promote working in multidisciplinary patient-oriented teams. Integrated Practice Units are defined as “organized around the patient and providing the full cycle of care for a medical condition, including patient education, engagement, and follow-up and encompass inpatient, outpatient and rehabilitative care as well as supporting services.” Although relatively few papers are published with empirical evidence on Integrated Practice Units development, some providers have impressively developed pathways and integrated care toward alignment with Integrated Practice Units criteria. From the field, we learn that possible advantages lay in improving patient centeredness, breaking through professional boundaries, and reducing waste in unnecessary duplications. A firm body of evidence on the added value of turning pathways into Integrated Practice Units is hard to find and this leaves room for much variation. Although intuitively attractive, this development requires staff efforts and costs and therefore cost-effectiveness and budget impact studies are much needed. Randomized controlled trials may be difficult to realize in organizational research, it is long known that turning to alternative designs such as larger case study series and before–after designs can be helpful. Thus, it can become clear what added value is achievable and how to reach that.

Keywords: Care pathways, health services research, management, organized care

It has been 12 years after Porter and Teisberg published their landmark manuscript on “Redefining Health Care,” followed by papers in Harvard Business Review and the New England Journal of Medicine further specifying various aspects of Value-Based Health Care (VBHC).1–3 Apart from stressing the need for a fundamental change from fee-for-service to value or outcome-based financing and to a focus on reducing waste, they emphasized the need to work along patient pathways and in Integrated Practice Units (IPU) to overcome function based and specialist group silos and promote working in multidisciplinary patient-oriented teams. They also advocated managed competition and – as a teaser on the cover – they promised significant cost reductions combined with quality improvements.

Notwithstanding the reach of the “VBHC movement,” apart from a certain “dilution” of the concept,4 one can question its evidence base, as so far only a few peer-reviewed analyses have been published.5 Especially, empirical evidence on the value equation and on the (financial) effects of implementing these principles is still lacking.6 It can however hardly be disputed that shifting to value and outcome in combination with multidisciplinary patient orientation is endorsed by many and potentially beneficial for the performance of health-care systems.

IPUs are defined as “organized around the patient and providing the full cycle of care for a medical condition, including patient education, engagement and follow up and encompass inpatient, outpatient and rehabilitative care as well as supporting services.” As is often the case when presenting their thoughts, in various fields such as oncology and vascular services, multidisciplinary care and integrated care pathways were already proposed and taking shape. In oncology, multidisciplinarity was required in many accreditation schedules, and this was reinforced by the VBHC movement.7,8

Care pathways and Integrated Practice Units

There are different models of integrated care available, that regard different levels of health system organization, a World Health Organization report in 2016 named at least three main types: (1) the chronic care model and the PRISMA model as examples of Integrated Service Delivery Systems, (2) disease specific integrated care models, and (3) population-based models.9

In pathways, we commonly deal with disease-specific models. Within a single organization, aspects such as alignment of functions, departments, and specialties, providing coordination and uniform information to patients and putting patients’ interests before that of units’ interests are important issues. Various authors have provided input on pathway development and pathway analysis using operations management techniques.10,11 Especially, when covering a process across organizations or in a network, less quantifiable aspects become increasingly important, such as:12

Structural Integration: financial-, legal ties;

Functional Integration: guideline or rule based;

Normative Integration: common culture, shared vision;

Interpersonal Integration: teamwork and professional cooperation;

Process Integration: single coordinated process across institutions;

Influenced by: external (market) context and internal organizational characteristics.

A caveat in this is that these aspects can be very dependent on local circumstances and less accessible for targeted intervention. One can however conclude that structuring and organizing mono- and multidisciplinary pathways within organizations has become common practice and is being increasingly ground in the literature and backed up by evidence-based and peer-reviewed material.8,13

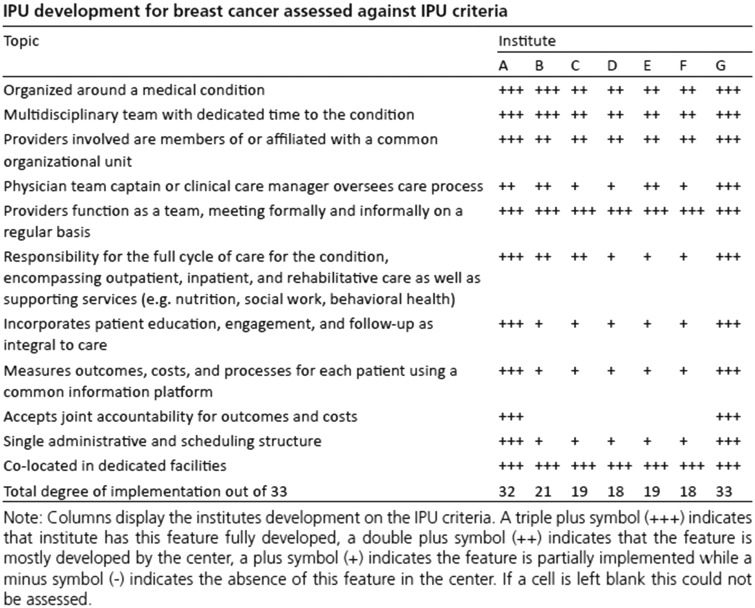

The definition that Porter provides on IPUs contains an additional set of characteristics that represents a further stage of development, such as more formal organizational of the team, the team’s finances, involving the “whole cycle of care,” and feedback on outcomes and costs. Recently, a benchmark was undertaken in seven European countries on the development of cancer pathways toward IPUs and found widely varying scores.14

Figure 1.

Scores on IPU criteria of benchmarked pathways European Cancer Centers.15

Nevertheless, some centers have impressively developed toward alignment with IPU criteria, possibly reflecting a trend in practice (Figure 1). It was concluded that the reported tool allows for the assessment of pathway organization and can be used to identify opportunities for improvement regarding the organization of care pathways toward IPUs.14

Evidence on added value of Integrated Practice Units

So far surprisingly few papers can be found in which IPU implementation is evaluated and screened on added value. Keswani et al. report on IPU development in orthopedics and mainly focus on design aspects and implementation barriers.16 Organizational issues such as striving for comprehensive IPU’s versus the use of shared services with other pathways, technological issues such as a portal or application to register and provide automated feedback on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and financing issues such as budget impact of aspects of care that are originally not within the coverage of the initial provider can hamper effective implementation. The latter could for instance be solved by bundled payments in which less restrictive rules are maintained considering the balance between inputs versus outcomes17; however, a very recent review reported mixed results on guideline adherence and costs.18 Caveats on wide implementation relate to the strict focus of IPUs versus comorbidity with which especially elderly patients are increasingly presenting. A comparable trend in “pseudo-understanding”4 may also be applicable to the IPU. A paper of Low et al. reported a significant reduction in readmissions in a modified virtual ward model shaped according to IPUs.19 The application of the IPU concept seemed however quite loose and superimposed on an earlier model of virtual wards meant to improve coordination of fragile patients care. Otherwise, no research comparing IPUs with other pathway service designs is published, which is rather surprising in view of the massive interest for VBHC.

In the hospital I lead as CEO (Rijnstate, a large teaching hospital in the Netherlands), the question was raised whether a critical paper on the achievements of VBHC was justified. The main outcry was that criticism on a range of aspects may be in place, IPU development is the one issue that merits support. We have developed the IPU principle in oncology, vascular diseases, palliative care, mother and child care, and trauma care in allocating budgets and space to a multidisciplinary team, giving them financial responsibility and starting to measure PROMs and perform outcome measurement with IPU-based dashboards. Subjective reactions were strong in emphasizing the added value in improving patient centeredness, breaking through professional boundaries, and reducing waste in unnecessary duplications. This is however a personal observation.

Further development and further research

It is clear from both the literature and practice that a firm body of evidence on the added value of turning pathways and teams into IPUs is hard to find. Moreover and apart from “dilution of the defined VBHC concept,” actual practice is lacking a strong empirical base and hence leaves room for much interpretation and implementation variation. Although intuitively attractive, this development requires management and staff efforts, restructuring costs and cost-effectiveness, and budget impact studies are much needed. Although randomized controlled trials may be difficult to realize in organizational research, it is long known that turning to alternative designs such as before and after studies, pragmatic trials and comparative case series can be sufficient to fill the most felt evidence gaps.20

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining health care. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee TH, Porter ME. The strategy that will fix healthcare. Boston: Harvard Business Review, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter ME. Standardizing patient outcomes measurement. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 504–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frederiksson JJ, Ebbevi D, Savage C. Pseudo-understanding: an analysis of the dilution of value in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf 2015; 24: 451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Ou L, Hollis SJ. A systematic review of the impact of routine collection of patient reported outcomes on patients, providers and health organisations in an oncologic setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JL, Maciejewski M, Raju S, et al. Value based insurance design: quality improvement but no cost savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013; 32: 1251–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saghatchian M, Thonon F, Boomsma F, et al. Pioneering quality assessments in European Cancer Centers. J Oncol Pract 2014; 10: e342–e349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borras JM, Albrecht T, Audiso R, et al. Policy statement on multidisciplinary cancer care. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50: 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO, Regional Office for Europe integrated care models: an overview. Geneva: World Health Organization, http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/322475/Integrated-care-models-overview.pdf (2016, accessed 19 October 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.VanHaecht K. The impact of clinical pathways on the organisation of processes. PhD dissertation, KU Leuven, Belgium, 2007.

- 11.Singer SJ, Keressey M, Freidberg M, et al. A comprehensive theory of integration. Med Care Res Rev Epub ahead of print 1 March 2018. DOI: 10.1177/1077558718767000 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Pluimers DJ, Van Vliet E, Niezink AG, et al. Development of an Instrument to analyze organisational characteristics in multidisciplinary care pathways: the case of colorectal cancer. BMC Res Notes 2015; 8: 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallhult E, Kenyon M, Liptrott S, et al. Management of veno occlusive disease: the multidisciplinary approach to care. Eur J Haematol 2017; 98: 322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wind A, Rocha Goncalves F, Marosi E, et al. Benchmarking cancer centers: from care pathways to integrated practice units. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018; 16: 1075–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wind A. Benchmarking comprehensive cancer care. Academic Thesis, University Twente, Enschede, 2017.

- 16.Keswani A. Value Based Health Care Part 2 – addressing the obstacles to implementing integrated practice units for the management of musculoskeletal disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016; 474: 2344–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aviki EM, Schleicher SM, Mullangi S, et al. Alternative payment and care-delivery models in oncology: a systematic review. Cancer 2018; 124: 3293–3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enthoven A, Crosson FJ, Shortell SM. Redefining health care: medical homes or archipelgos to navigate? Health Affairs 2007; 26: 1366–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Low LL, Tan SY, Ng MJ, et al. Applying the integrated practice unit concept to a modified virtual ward model of care for patients with highest risk of readmission. A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0168757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Harten WH, Casparie TF, Fisscher OA. Methodological considerations on the assessment of the implementation of quality management systems. Health Policy 2001; 54: 187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]