Abstract

Background

Same-day colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) immediately following incomplete optical colonoscopy (OC) would have a number of advantages for patients, while also presenting unique procedural challenges including the effect of sedation on capsule propulsion and patient tolerance of protracted preparation and fasting.

Aim

The aim of this article is to prospectively assess the efficacy of same-day CCE after incomplete OC in an unselected patient cohort.

Methods

This was an observational, prospective, single-centre study of CCE post-incomplete colonoscopies. Patients with an incomplete OC for any reason other than obstruction or inadequate bowel preparation were recruited. CCE was performed after a minimum of a one-hour fast. Once the patient was fully alert, intravenous metoclopramide was administered after capsule ingestion when possible, and a standard CCE booster protocol was then followed. Relevant clinical information was recorded. CCE completion rates, findings and their impact, and adverse events were noted.

Results

Fifty patients were recruited, mean age = 57 years and 66% (n = 32) were female. Seventy-six per cent (n = 38) of CCEs were complete; however, full colonic views were obtained in 84% (n = 42) of cases. Patients > 50 years of age were five times more likely to have an incomplete CCE and there was also a trend towards known comorbidities associated with hypomobility having reduced excretion rates. Overall diagnostic yield for CCE in the unexplored segments was 74% (n = 37), with 26% (n = 13) of patients requiring significant changes in management based on CCE findings. The overall incremental yield was 38%. CCE findings were normal 26% (n = 13), polyps 38% (n = 19), inflammation 22% (n = 11), diverticular disease 25 (n = 12), angiodysplasia 3% (n = 1) and cancer 3% (n = 1). Significant small bowel findings were found in three (6%) cases, including Crohn’s disease and a neuroendocrine tumour. A major adverse event occurred in one patient (2%), related to capsule retention.

Conclusion

Same-day CCE is a viable alternative means to assess unexplored segments of the colon after incomplete OC in selected patients.

Keywords: Colon capsule endoscopy, incomplete colonoscopy, capsule endoscopy, endoscopy, optical colonoscopy

Key summary

Established knowledge on the subject

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) is a new, noninvasive novel technique for exploring the large intestine.

Recent studies demonstrate good correlation between optical colonoscopy (OC) and CCE in detection of both significant and nonsignificant large bowel pathology.

The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommend CCE as a potential and safe means for obtaining sufficient colonic views in patients with incomplete OC without evidence of obstruction.

Significant/New findings of this study

The administration of CCE on the same day of incomplete colonoscopy is safe and feasible in the majority of patients with a significant diagnostic yield of 74% with an incremental yield of 38%.

Its use is likely to be restricted to a few patients in the setting of incomplete colonoscopy as only 50 same-day cases were completed in two years at our institution. This is not an entirely unexpected finding for a combination of reasons, including improved colonoscopy standards as well as the exclusion of those individuals in whom colonoscopy was limited by inadequate preparation.

But for those who do need it, CCE provides an adequate alternative and a good complementary procedure following incomplete OC.

Same-day CCE avoids the need for repeat bowel preparation and delayed diagnoses for patients and enables prompt treatment decisions. It also relieves some of the ever-growing burden on endoscopy and radiology services, particularly in the era of bowel screening programmes.

Background

Colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) is a new, noninvasive novel technique for exploring the large intestine. Recent studies demonstrate good correlation between OC and CCE in detection both of significant and nonsignificant large bowel pathology.1–4 The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommend CCE as a potential and safe means for obtaining sufficient colonic views in patients with incomplete OC without evidence of obstruction.5 Caecal intubation rates of greater than 90% and 95% are the current recommendations for routine and screening colonoscopies, respectively.6 Rates of incomplete colonoscopy can range from 2% to 19%.7 Currently those patients with incomplete colonoscopies for a variety of reasons, including procedure intolerance, poor bowel preparation, and fixed loops of colon, are subjected to a repeat colonoscopy or radiographic imaging as a means of obtaining appropriate colonic visualisation. This unfortunately frequently involves a repeat day of fasting, intensive bowel preparation and can even result in significant diagnostic delays.

A recent prospective trial by Spada et al. compared CCE to computed tomography (CT) colonography after incomplete OC and found that although both tests are an effective means of colonic visualisation post-incomplete OC, CCE appears to be more sensitive at detecting medium sized (6–9 mm) polyps, and also removes the need for radiation exposure.8 In addition, a multicentre trial by Triantafyllou et al. further validated the use of CCE after incomplete colonoscopy by demonstrating its ability to yield significant findings, guide further workup, as well as finding a high level of patient acceptance.9 Interestingly, this study compared groups of patients who underwent same-day (n = 25) and delayed CCE and found no difference in colonic lesion detection rates between the two groups. However, there have been no studies to date specifically examining the feasibility of same-day CCE after incomplete colonoscopy, which may offer a more convenient and cost-effective mode of colonic examination post-incomplete colonoscopy.

Study aims and methods

The aim of our study was to explore the feasibility of same-day CCE post-incomplete colonoscopy. Specifically, we hoped to examine the potential limiting factors, including adequacy of bowel preparation, the impact of sedation, bowel insufflation, or antispasmodics used during colonoscopy, which may affect subsequent CCE interpretation. The study objectives are summarised below.

Primary objectives

1. Overall completion rates defined as:

a) CCE reaching the dentate line

b) Partial completion – CCE reaching the limit of colonoscopy insertion

2. Preparation quality – as defined by a standard bowel cleansing form10 (Appendix 1)

3. Clinically significant findings defined as:

a) >6 mm polyp, or >3 polyps in any one individual

b) Detection of any other colonic abnormality including inflammation, malignancy, or significant diverticular disease which had clinical implications for the patients

4. Adverse events

Secondary objectives

Clinical implications of the findings, i.e. adjustments in patient’s treatment based on CCE findings

Confirmation of finding on follow-up colonoscopy if indicated – positive predictive value of CCE

Study design

This was an observational, prospective assessment of CCE in an unselected incomplete OC cohort from July 2015 to 2017 at our institution. CCE following incomplete OC is an approved recognised standard of care, and as such the need for ethical approval was discussed with the joint St. James’s and Tallaght Hospital Ethics Committee. Written confirmation from the ethics committee was received on 7 May 2015 that formal ethics approval was not required for this study as it was an observational study of an already approved standard of care. Following informed written consent, all patients aged 18 years and older who had an incomplete standard OC for reasons other than poor bowel preparation or suspected obstruction of the colonic lumen were invited to participate in the study following an appropriate recovery time of one-hour post-colonoscopy. Patients were required to be capable of providing informed consent and be capable of ingesting further bowel preparation. Participants were excluded if they had any of the following: a known or suspected small or large bowel stricture or obstruction, dysphagia, recent (within the last six weeks) abdominal surgery, any significant renal impairment, any contraindication to bowel preparation, an allergy to any study medication, diabetes with significant hypo/hyperglycaemia or any serious medical illness, an inability to provide informed consent, known or suspected complication post-colonoscopy including hypotension, abdominal pain, bleeding or perforation, or inadequate bowel preparation.

Procedure description

All initial colonoscopies were performed in accordance with national endoscopy guidelines, using conscious sedation with a mixture of fentanyl, midazolam and hyoscine bromide after a standard bowel cleansing agent, including polyethylene glycol, MoviPrep, or sodium picosulfate/magnesium citrate in accordance with National and International Quality in Endoscopy Standards. At the time of endoscopy, the proximal site of insertion was marked via placement of an endoscopic clip or a tattoo. Reasons for incomplete studies were noted. Eligible patients were invited to undergo CCE after a minimum of one-hour recovery time, once they were fully alert. As outlined in Table 1, upon attachment of the digital recorder device and ingestion of the capsule, when feasible, 10 mg of intravenous (IV) metoclopramide was given to overcome the antimotility effects of fentanyl given during endoscopy. Second-generation (CCE-2) PillCam colon capsules (Medtronic/Given Imaging, Yokneam, Israel) were used. Patients were monitored until the capsule reached the small intestine, at which point a booster of sodium phosphate (Fleet Phospho-Soda) was given (Table 1). This was followed by the ingestion of a mixture of oral gastrografin (diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium) and 1 l of water. It was at this point patients could leave the endoscopy department. Patients were advised to take a second booster of sodium phosphate approximately three hours later, in addition to gastrografin (diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium) and water. Patients could eat and drink following their second booster. If the patient failed to see the capsule pass within 10 hours of ingestion of the capsule, they were advised to administer a 10 mg rectal bisacodyl suppository (Table 1).

Table 1.

Colon capsule endoscopy procedure.

| Day 0 | Standard 4 l of polyethylene glycol, liquid diet. |

| Day 1: 09:00 | Incomplete colonoscopy. |

| Day 1: 1 hour post-colonoscopy | Patient invited to participate in the study. |

| Day 1: 90 minutes post-incomplete colonoscopy | Digital recorder attached/capsule swallowed + 10 mg intravenous metocloperamide administered if no contraindications |

| Small bowel reached | First booster of sodium phosphate, 40 ml + 50 ml of gastrografin followed by 1 l of water Patients can leave the endoscopy department. |

| Three hours later | Second booster of sodium phosphate, 25 ml + 25 ml of gastrografin + 0.5 l of water Patient can then eat and drink normally one hour after second booster |

| Ten hours post-capsule ingestion | If not passed, rectal bisacodyl suppository used |

Patients were requested to return the recorder to the endoscopy department the next day. An experienced physician in CCE would then review the CCE video by using RAPID software (Medtronic/Given Imaging, Yokneam, Israel). Study findings were reported and appropriate follow-up arranged. Patient demographics, indication for, initial colonoscopy findings, and sedation levels were recorded, along with key CCE data including preparation quality, completion and positivity rates, adverse events and impact on patient management.

Results

In all 50 same-day CCEs have been completed at our institution. The mean age was 57 years (22–83 years) and 66% (n = 32) were female. Indications for OC were altered bowel habit 30% (n = 15), iron deficiency anaemia 26% (n = 13), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) assessment 16% (n = 8), peri-rectal bleeding 6% (n = 3), abdominal pain 6% (n = 3), polyp surveillance 6% (n = 3), positive family history of colorectal cancer 8% (n = 4) and abnormal imaging 2% (n = 1) (Table 2). The reasons for incomplete colonoscopies were excessive looping 43% (n = 21), patient intolerance 29% (n = 15) and severe diverticular disease 26% (n = 13). The mean sedation used during OC was 5 mg midazolam (range 3–10 mg) and 75 mcg of fentanyl (range, 50–100 mcg).

Table 2.

Patient cohort characteristics and data in relation to incomplete colonoscopies.

| Total number | N = 50 |

| Female patients | N = 32 (66%) |

| Mean age | 57 years (22–83 years) |

| Indications | |

| Altered bowel habit | N = 15 (30%) |

| Iron deficiency anaemia | N = 13 (26%) |

| PR bleeding | N = 3 (6%) |

| Abdominal pain | N = 3 (6%) |

| Polyp surveillance | N = 3 (6%) |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | N = 4 (8%) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease assessment | N = 8 (16%) |

| Abnormal imaging | N = 1 (2%) |

| Reason for failed colonoscopy | |

| Looping | N = 21 (42%) |

| Patient discomfort | N = 15 (30%) |

| Diverticular disease | N = 14 (28%) |

In all only 76% (n = 38) of CCEs were complete; however, full colonic views were obtained in 84% (n = 42) of cases. Mean colonic passage time was 233 minutes, and overall image quality was deemed to be excellent in 16% (n = 8), good in 31% (n = 16), adequate in 44% (n = 22) and poor in only 9% (n = 4) of participants (Table 3). Overall 58% (n = 28) of patients received polyethylene glycol (PEG) precolonoscopy, 40% (n = 20) MoviPrep and 4% (n = 2) sodium picosulphate. Amongst these, no significant differences in CCE completion rates were noted based on bowel preparation used (PEG (n = 20), MoviPrep (n = 16) (p = 0.5) and sodium picosulphate (n = 2)).

Table 3.

Procedure completion rates and image quality.

| Complete colon capsule endoscopy procedures | 38 (76%) |

| Overall complete colonic exam rate | 42 (84%) |

| Mean colon passage time | 233 minutes |

| Image quality | |

| Poor | 4 (9%) |

| Adequate | 22 (44%) |

| Good | 16 (31%) |

| Excellent | 8 (16%) |

In terms of findings, there was more than one abnormality detected in some cases. OC findings prior to CCE were normal in 76% (n = 38), diverticular disease in 24% (n = 12) and polyps which were removed in 12% (n = 6).

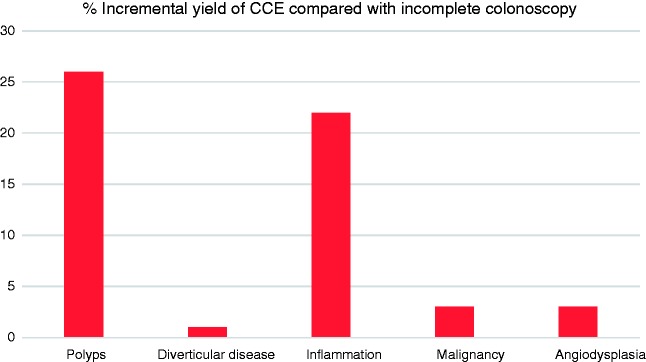

Overall diagnostic yield for CCE was 74% (n = 37) with overall incremental yield of 38% (n = 19). In all 26% (n = 13) of patients required significant changes in management based on CCE findings. CCE findings were normal 26% (n = 13), polyps 38% (n = 19), inflammation 22% (n = 11), diverticular disease 25% (n = 12), angiodysplasia 3% (n = 1), and cancer 3% (1) (Figure 1). Amongst the patients who had polyps (n = 19), seven (36%) were deemed to have significant polyps and required referral for polypectomy. Of these, four patients had a polyp > 6 mm and three patients had ≥ 3 polyps. Subsequent histology of these polyps referred for removal (n = 14) revealed tubulovillous adenoma with low-grade dysplasia in 57% of cases (n = 8), tubulovillous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia in 7% (n = 1), sessile-serrated adenoma in 14% (n = 2) and hyperplastic polyps in 21% (n = 3). As per ESGE guidelines,2 the remaining patients without significant polyps, <6 mm, were scheduled for repeat CCE screening in five years.

Figure 1.

Incremental yield of colon capsule endoscopy (CCE) compared with incomplete colonoscopies.

Based on the CCE findings, four (36%) of the IBD patients required therapy escalation and the patient with significant caecal angiodysplasia was referred for cauterisation.

In terms of the patient with a detected malignancy, this was actually noted incidentally in the small bowel and this was later confirmed as a neuroendocrine tumour on double-balloon enteroscopy, and the patient was referred for surgical resection. Other significant incidental small bowel findings included two patients with a new diagnosis of small bowel Crohn’s disease.

In terms of adverse events, two (4%) patients reported abdominal pain related to bowel preparation and one (2%) patient retained the capsule secondary to a small bowel stricture secondary to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use which later required surgical resection.

Amongst the 12 (24%) patients with incomplete CCE studies, four (33%) were related to poor preparation whereas the remaining eight (76%) failed to demonstrate full colonic views during recording. Of interest, the majority in whom complete colonic visualisation failed to be achieved, 66% (n = 8), were > 50 years of age vs 34% (n = 13) who completed the test, p = 0.04, 95% confidence interval –0.65 to 00, with an odds ratio of 5.2, p = 0.017. Relevant comorbidities which could potentially influence gut motility, such as diabetes and parkinsonism, were also higher amongst those with incomplete studies but did not reach statistical significance (50% (n = 6) vs 29% (n = 11) p = 0.2). In terms of mean sedation, those with complete studies had received slightly less sedation but this did not meet statistical significance, complete (mean sedation, midazolam 4 mg fentanyl 50 mcg) vs incomplete (midazolam 4 mg and fentanyl 75 mcg), p = 0.2 and p = 0.4, respectively. Bowel preparation was deemed to be poor in 8% (n = 4) patients overall, and all of these patients had incomplete studies.

Discussion

This prospective, single-centre study confirms the efficacy of same-day CCE for incomplete OC with an overall colonic visualisation rate of 84% (n = 42) and overall CCE completion rate of 76% (n = 38). Unlike other studies the proximal site of insertion was marked with a tattoo or endoscopic clip to ensure full colonic views were achieved during our study. Overall diagnostic yield for CCE was 74% (n = 37), with 26% (n = 13) of patients requiring significant changes in management based on CCE findings. These data compare favourably with other published CCE-2 studies to date.9,11 One study completed by Nogales et al. examined results from 96 patients from multiple Spanish centres from 2010 to 2013 who underwent CCE within 72 hours to one week following incomplete OC. Similar to our own study, complete visualisation of the colon was obtained with CCE-2 in 69 patients (71.9%) with an overall combined completion rate using OC and CCE of 92.7%.11 The diagnostic yield of CCE in this study for detecting colonic lesions in unexplored colonic segments was 60.4% with an overall impact of CCE on therapy in 44.8% of all patients.

Certainly, one of the limitations of our study relates to bowel preparation and capsule propulsion, since complete visualisation of the colon with CCE was possible in only 74% of individuals. Our study highlights the specific challenges of same-day CCE in terms of patient selection and bowel preparation optimisation. Incomplete colonic views based on CCE alone were noted in 16% of patients, and 66% of these patients were > 50 years old compared with 30% with a complete CCE. Potential comorbid conditions such as diabetes and Parkinson disease could represent potentially significant influences on both gastric motility as well as overall bowel preparation which may influence potential future same-day CCE patient selection. Although the study sample size is a limited number and a valid consideration when evaluating potential risk factors for CCE incompleteness, numbers are comparable if not superior to already published data relative to CCE after incomplete OC.8,11,12 Certainly, CT colonography may be a more appropriate selection in these individuals. Mean sedation used during OC (complete vs incomplete, mean fentanyl 50 mcg vs 75 mcg) was also higher overall in those with incomplete CCE although this did not quite reach statistical significance. Clinicians should be mindful of the impact of increased sedation on those patients in whom CCE may be a viable option with difficult colonoscopies, although IV metocloperamide is recommended to overcome the antimotility effects of sedation. Overall bowel preparation was poor in 8% of patients overall, despite excluding patients with poor bowel preparation during OC from participation. Further studies to optimise the bowel preparation regimen are needed to standardise and expand the use of CCE, including in cases of incomplete OC. Rex et al. reported slightly better results from a trial in the United States in which sodium phosphate was replaced by Suprep (sodium sulphate, potassium sulphate and magnesium sulphate) (Braintree Lab Inc, USA), maintaining the split dose of PEG.13 Other studies have reported 2 l PEG + ascorbic acid preparation as better than the standard 4 l PEG,14 and it may also be used as a booster.15 As yet there is no clear benefit for any given regimen and the optimal preparation for CCE requires further investigation.

Our study also reinforces the benefits of panenteric visualisation provided by CCE, with 10% (n = 5) of patients with significant findings in the small bowel, namely inflammation (n = 4), as well one case of small bowel malignancy. The benefits of CCE panenteric views have been highlighted in past studies by Hall et al.16 and Romero-Vázquez et al.17

In terms of safety overall, one patient had a significant complication with CCE, i.e. capsule retention secondary to an inflammatory stricture related to NSAID use. Again, this highlights the need for careful patient selection based on potential obstructive symptoms as well as risks for retention based on careful history taking.

In summary, the administration of CCE on the same day of incomplete OC is safe and feasible in the majority of patients with a significant diagnostic yield of 74%. Its use is likely to be restricted to a few patients in the setting of incomplete OC as only 50 same-day cases were completed in two years in our institution, as expected with improved OC standards and excluding those in whom OC was limited by inadequate preparation. But for those who do need it, CCE provides an adequate alternative and is a good complementary procedure following incomplete OC. Same-day CCE avoids the need for repeat bowel preparation and delayed diagnoses for patients and enables prompt treatment decisions. It also relieves some of the ever-growing burden on endoscopy and radiology services, particularly in the era of bowel screening programmes.

Appendix 1

Bowel cleansing assessment form

| Cleansing level scale | Rating | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Poor | Inadequate Large amount of faecal residue precludes a complete examination | |

| Fair | Inadequate but examination completed Enough faeces or turbid fluid to prevent a reliable examination | |

| Good | Inadequate but examination completed Enough faeces or turbid fluid to prevent a reliable examination | |

| Excellent | Adequate No more than small bits of adherent faeces | |

| Bubbles effect scale | Significant | Bubbles that interfere with the examination More than 10 % of surface area obscured by bubbles |

| Insignificant | No bubbles or bubbles that do not interfere with the examination Less than 10 % of surface area obscured by bubbles |

Declaration of conflicting interests

The capsules used in this research project were funded by Medtronic medical device company as part of a research-funded project.

Funding

Capsules were provided by medtronic as part of a research funded project.

Ethics approval

Written confirmation from the joint St. James’s and Tallaght Hospital Ethics Committee was received on 7 May 2015 that formal ethics approval was not required for this study as it was an observational study of an already approved standard of care.

Informed consent

All patients provided informed written consent.

References

- 1.Pioche M, de Leusse A, Filoche B, et al. Prospective multicenter evaluation of colon capsule examination indicated by colonoscopy failure or anesthesia contraindication. Endoscopy 2012; 44: 911–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herrerías-Gutiérrez JM, Argüelles-Arias F, Caunedo-Álvarez A, et al. PillCamColon capsule for the study of colonic pathology in clinical practice. Study of agreement with colonoscopy. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2011; 103: 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gay G, Delvaux M, Frederic M, et al. Could the colonic capsule PillCam Colon be clinically useful for selecting patients who deserve a complete colonoscopy? Results of clinical comparison with colonoscopy in the perspective of colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 1076–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sieg A, Friedrich K, Sieg U. Is PillCam COLON capsule endoscopy ready for colorectal cancer screening? A prospective feasibility study in a community gastroenterology practice. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 848–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spada C, Hassan C, Galmiche JP. Colon capsule endoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy 2012; 44: 527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 873–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holleran G, Leen R, O’Morain C, et al. Colon capsule endoscopy as possible filter test for colonoscopy selection in a screening population with positive fecal immunology. Endoscopy 2014; 46: 473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spada C, Hassan C, Barbaro B, et al. Colon capsule endoscopy versus colonography in the evaluation of patients with incomplete traditional colonoscopy: A prospective comparative trial. United European Gastroenterol J 2013; 1(Suppl 1): A126–A126. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Triantafyllou K, Viazis N, Tsibouris P, et al. Colon capsule endoscopy is feasible to perform after incomplete colonoscopy and guides further workup in clinical practice. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 79: 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leighton J, Rex D. A grading scale to evaluate colon cleansing for the PillCam COLON capsule: A reliability study. Endoscopy 2011; 43: 123–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nogales Ó, García-Lledó J, Luján M, et al. Therapeutic impact of colon capsule endoscopy with PillCam™ COLON 2 after incomplete standard colonoscopy: A Spanish multicenter study. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2017; 109: 322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baltes P, Bota M, Albert J, et al. PillCam Colon2 after incomplete colonoscopy – First preliminary results of a multicenter study. United European Gastroenterol J 2013; 1(Suppl 1): A190–A190. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rex DK, Adler SN, Aisenberg J, et al. Accuracy of PillCam COLON 2 for detecting subjects with adenomas ≥ 6 mm. Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 77: AB29–AB29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Argüelles-Arias F, San-Juan-Acosta M, Belda A, et al. Preparations for capsule endoscopy. Prospective and randomized comparative study between two preparations for colon capsule endoscopy: PEG 2 litres + ascorbic acid versus PEG 4 litres. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2014; 106: 312–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiménez-Garcia VA, Arguelles-Arias F, Romero-Vásquez J, et al. Comparative study of three protocols to cathartic preparation for the study of colon by PillCam Colon. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: S–771. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall B, Holleran G, McNamara D. PillCam COLON 2 as a pan-enteroscopic test in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7: 1230–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero-Vázquez J, Caunedo-Álvarez Á, Belda-Cuesta A, et al. Extracolonic findings with the PillCam Colon: Is panendoscopy with capsule endoscopy closer? Endosc Int Open 2016; 4: E1045–E1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]