Abstract

Background

Helicobacter pylori is transmitted through faecal-oral or oral-oral routes. Whether H. pylori infection is more prevalent in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects is unclear.

Objective

We evaluated 1) the prevalence of H. pylori infection in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects; and 2) whether presence of gastroesophageal reflux in H. pylori-infected subjects was associated with transmission of infection to their sexual partners.

Methods

We evaluated H. pylori infection by 13C Urea Breath Test in sexual partners of 161 consecutive patients with H. pylori-related dyspepsia. The case-control group consisted of 161 dyspeptic subjects undergoing the 13C Urea Breath Test. The prevalence of reflux symptoms was noted through the Leeds scale. The role of gastroesophageal reflux in transmission of H. pylori infection was evaluated by binary logistic regression. A two-tailed p value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Results

Prevalence of H. pylori infection in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects is 74.5% whereas prevalence of H. pylori infection in the control group is 32.3%, p<0.05. At the logistic regression analysis, the presence of reflux symptoms in H. pylori-infected subjects is independently associated with concomitant infection in both members of the couple (odds ratio 4.41, 95% confidence interval 1.6–12.3) and with length of cohabitation (odds ratio 2.39, 95% confidence interval 1.0–5.7).

Conclusions

The prevalence of H. pylori infection is significantly higher in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects than in controls. Members of a couple are four times more likely to be both H. pylori infected if one of the couple has reflux symptoms.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, sexual partner, transmission, gastroesophageal reflux, cohabitation

Key summary

Summarise the established knowledge on this subject:

‐ H. pylori is transmitted through faecal-oral or oral-oral routes.

‐ It is not completely clear whether H. pylori infection is more prevalent in the sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

‐ The prevalence of H. pylori infection is significantly higher in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects than in controls.

‐ Members of a couple are four times more likely to be both H. pylori infected if one of the couple has reflux symptoms.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic, spiral-shaped, flagellated Gram-negative bacillus that colonizes human gastric mucosa. H. pylori is a definite carcinogen in human beings, triggering the progressive sequence of gastric lesions that from chronic gastritis, through gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia eventually lead to distal gastric cancer.1 The prevalence varies with geographic regions, age and socioeconomic status ranging from 39.9% to 84.2%.2 The world’s average prevalence of H. pylori infection was estimated at around 58%.3

Despite being one of the world’s most widespread infections, the route of transmission of H. pylori infection is still partially unclear. The reservoir of H. pylori is the human stomach and its transmission likely occurs because of direct human-to-human transmission or environmental contamination. Person-to-person transmission can be subdivided into vertical and horizontal transmission. Vertical transmission consists of familial transmission between parents and children, whereas horizontal transmission involves contact with individuals outside the family, including environmental contamination.4

Although there is evidence supporting the existence of oral-oral, gastro-oral and faecal-oral transmission, it is still not possible to define the main route of transmission.

Furthermore, it is not completely clear whether H. pylori infection is more prevalent in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects. Some authors5 suggest that conjugal transmission could only be relevant in a high prevalence population, whereas different studies describe a strong relationship between H. pylori infection and the H. pylori status of partners.6–9

Our aim here is to evaluate the prevalence of H. pylori infection in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected individuals. Moreover, we evaluated whether the presence of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) symptoms, and acidic regurgitation in particular, in H. pylori-infected subjects was associated with a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection in their sexual partners.

Materials and methods

Study design and study population

Between January 2016 and March 2017, in our department we prospectively enrolled patients with dyspeptic symptoms to perform a 13C Urea Breath Test (UBT). The following individuals were excluded: 1) those who had received antibiotics, bismuth compounds, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID); and 2) those with history of peptic ulcer. Written, informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

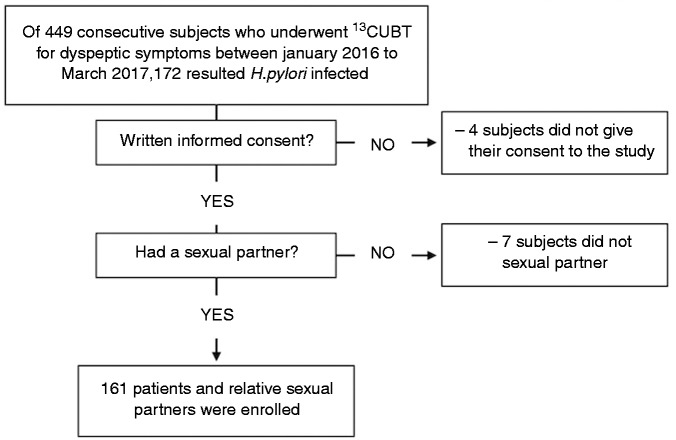

Based on the above criteria, of the 449 consecutive patients who underwent the breath test, 161 H. pylori -positive individuals were enrolled (index group) (78 males and 83 females, mean age ± standard deviation (SD) 40.7 ± 12.0 years, range 18–76 years). The flow diagram of the recruitment process is shown in Figure 1. Sexual partners of these 161 subjects also met these criteria and gave their consent to participate in the study (partner group) (84 males and 77 females, 40.5 ± 12 years, range 18–80 years). Similarly, these partners also underwent a 13C UBT. We considered sexual partners as the boyfriend, girlfriend or spouse of the H. pylori-infected subjects. All of the participants in the study were Caucasian Italians. Age, sex, level of instruction, smoking, weight, height, intercurrent cohabitation and duration of the cohabitation were recorded. Moreover, the prevalence and frequency of GER symptoms was assessed using the short-form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire (sf-LDQ), which was administered to both groups. In total, 161 subjects who were referred to our Gastroenterology Unit to perform 13C UBT for dyspeptic symptoms were matched for sex and age (74 males and 87 females, 42.4 ± 11.9 years, range 18–80 years) and enrolled as case-control group and assessed, also, for GER symptoms through the sf-LDQ.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of recruitment process.

This study received post hoc approval from the Ethical Committee of the Department of Polyspecialistic Internal Medicine “Luigi Vanvitelli” University Hospital on 22 May 2018. The protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

H. pylori test

The 13C UBT was performed through Breath ID system10 (Sofar, Italy), which allows collection of breath samples continuously from a patient before and after 13C-enriched urea administration. Following a base-line period, patients are administered 75 mg 13C urea (tablet) and 4.5 g citric acid-based powder as a drink. The ID circuit, a nasal breath sampling device, continuously transports the breath sample from the patient to the Breath ID. The determination of positive or negative results is based on a device algorithm. After 5 min, if more than two points are above six delta over baseline (DOB), the patient is considered positive. If more than two points are below three DOB, the patient is considered negative. This method has shown an accuracy comparable with standard 13C UBT in 217 dyspeptic subjects (104 naive to H. pylori testing and 113 after eradication therapy) who performed both tests on the same occasion with a concordance of results of 100% (M Romano, unpublished observations).

sf-LDQ

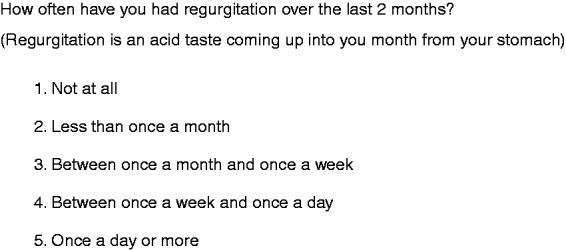

The sf-LDQ11 consists of four questions from the LDQ,12 which is long and not designed for self-completion. Each question comprises two stems concerning the frequency and severity of each symptom during the last 2 months. Moreover, it also contains a single question concerning the most troublesome symptom experienced by the patient to enable categorization of patients based on predominant heartburn or epigastric pain.

In our study, we only evaluated the prevalence and frequency of GER symptoms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Short-form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire (sf-LDQ) related to frequency of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) symptoms.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and the exact test as appropriate. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare means. Binary logistic regression was used to evaluate the relationship between the presence of H. pylori infection in partner group (no/yes = 0/1) as the dependent variable and possible predictors as the independent variables. The model was estimated using a block entry of variables. In this multivariate analysis, we used the variables GER symptoms (coded 0/1 = no/yes), sex (male/female = 0/1), body mass index (BMI), smoking (no/yes = 0/1) and intercurrent cohabitation (no/yes = 0/1). Because cohabitation and age of couples are dependent variables and therefore influence each other, we chose cohabitation rather than age in our binary logistic regression. The coefficients obtained from the logistic regression analyses were also expressed in terms of odds of occurrence of an event. A two-tailed p value of 0.05 or less was considered significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

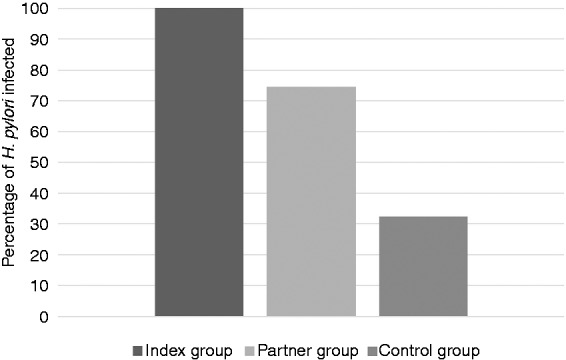

No statistical differences were described for BMI, level of instruction and smoking between index, partner and the control group (Table 1). The prevalence of H. pylori infection in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects was 120/161 (74.5%) whereas the prevalence of H. pylori infection in the control group was 52/161 (32.3%), p<0.001 (Figure 3). The prevalence of GER symptoms is more common in couples with both members infected than in those with only one member infected (Table 2). Members of 117 couples out of 161 (72.7%) were living together and, in 53/117 couples (45.3%), the length of cohabitation was longer than 15 years (data not shown). By logistic regression, the presence of GER symptoms in subjects of the index group is independently associated with transmission of infection to partners (odds ratio (OR) 4.4, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.6–12.3). Also, the length of cohabitation is an independent risk factors for transmission of H. pylori infection (OR 2.39, 95% CI 1.0–5.7) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Subjects’ baseline characteristics.

| Index group (n = 161) | Partner group (n = 161) | Control group (n = 161) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 78 (48.4) | 84 (52.2) | 74 (46.0) | 0.53 |

| H. pylori infection | 161 (100) | 120 (74.5) | 52 (32.3) | <0.001a |

| Age, mean (SD) | 40.7 (12.0) | 40.5 (12.0) | 42.4 (11.9) | 0.26 |

| Pts with regurgitation symptoms | 138 (85.7) | 46 (28.6) | – | <0.001 |

| Regurgitation frequency | <0.001 | |||

| − not at all | 23 (14.3) | 115 (71.4) | – | |

| − less than once a month | 20 (12.4) | 22 (13.7) | ||

| − between once a month and once a week | 26 (16.1) | 14 (8.7) | ||

| − between once a week and once a day | 49 (30.4) | 5 (3.1) | ||

| − once a day or more | 43 (26.7) | 5 (3.1) | ||

| BMI, mean (SD) | 24.4 (2.8) | 23.8 (2.8) | 23.8 (2.7) | 0.10 |

| BMI grade | ||||

| − underweight | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) | 0.44 |

| − normal | 88 (54.7) | 102 (63.4) | 107 (66.5) | |

| − overweight | 68 (42.2) | 53 (32.9) | 50 (31.3) | |

| − obesity grade I | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) | 3 (1.9) | |

| Instruction | – | 0.63 | ||

| − no instruction | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.9) | ||

| − elementary school | 4 (2.5) | 4 (2.5) | ||

| − middle school/diploma | 51 (31.7) | 62 (38.5) | ||

| − graduate degree | 103 (64.0) | 92 (57.1) | ||

| Smoking | 93 (57.8) | 85 (52.8) | 82 (50.9) | 0.44 |

Data are n (%) except when indicated.

BMI: body mass index; pts: patients; SD: standard deviation.

Control group vs partner group.

Figure 3.

Percentage of H. pylori infection in the three groups.

Table 2.

Prevalence and frequency of GER symptoms in couples with both members infected and in couples with only one member infected or without partners infected.

| Couples with both members infected (n=120) | Couples with one member infected (n=41) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regurgitation, n (%) | 110 (91.7) | 28 (68.3) | <0.001 |

| Regurgitation frequency, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| − not at all | 10 (8.3) | 13 (31.7) | |

| − less than once a month | 15 (12.5) | 5 (12.2) | |

| − between once a month and once a week | 15 (12.5) | 11 (26.9) | |

| − between once a week and once a day | 43 (35.8) | 6 (14.6) | |

| − once a day or more | 37 (30.9) | 6 (14.6) |

GER: gastroesophageal reflux.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis examining the relationship between the presence of GER symptoms in H. pylori-infected subjects (no/yes=0/1) as the dependent variable and other independent variables. The coefficients obtained from the logistic regression analysis were also expressed in term of the odds of occurrence of an event.

| Variable | Regression coefficient | SE | p value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GER symptoms | 1.485 | 0.524 | 0.005 | 4.41 | 1.58-12.33 |

| Sex | −0.070 | 0.411 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.41-2.08 |

| BMI | 0.130 | 0.079 | 0.10 | 1.13 | 0.97-1.32 |

| Smoking | 0.391 | 0.401 | 0.33 | 1.47 | 1.67-3.24 |

| Length of cohabitation | 0.873 | 0.441 | 0.04 | 2.39 | 1.00-5.68 |

| Constant | −4.055 |

BMI: body mass index; GER: gastroesophageal reflux; SE: standard error of estimated coefficient; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects are at a higher risk of being infected especially if one of the couple has GER.

The risk of infection among sexual partners of H. pylori-positive subjects has been evaluated by several studies with conflicting results. In 1996, Parente et al.6 raised the question of whether serological screening of partners of H. pylori-infected subjects with duodenal ulcers might be indicated. In their study, the authors showed that the spouse of a patient with a duodenal ulcer had a significantly higher seroprevalence of H. pylori infection than controls (71% vs 58%, p<0.05).

In a cohort of women who gave birth to healthy children at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Ulm, Brenner et al.5 evaluated the prevalence of H. pylori in their partners. Of 670 patients, 14.5% were H. pylori positive as measured by 13C UBT when the corresponding partner was negative compared with 35.9% of women with an H. pylori positive partner (OR 3.17; 95% Cl 2.08–4.81). At subanalysis for nationality, this association was reduced to OR 1.71 (95% Cl 1.03–2.86): in fact, within the overall population, 12.4% of women and 13.3% of men had a nationality other than German (29% were Turkish participants with a higher H. pylori prevalence). The authors concluded that conjugal transmission is unlikely to be of relevance in low-prevalence populations, but it could be relevant in high-prevalence populations.

A randomly selected sample of the general population living in a small town in central England (Market Harborough) was involved in a serological study for H. pylori infection using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test and 13C UBT as well when serological results were borderline. Out of 389 married couples tested, in 19 cases both partners were positive, in 287 cases both the husband’s and wife’s results were negative; only one partner was H. pylori infected in the remaining couples. Comparing H. pylori infection in partners with an H. pylori-positive spouse to those with an H. pylori-negative spouse, the OR was 3.18 (95% Cl 1.69–5.99).7

Singh et al.8 tested the H. pylori status of 25 couples, with one individual per couple selected as the index subject. Among infected index patients, 15 had an H. pylori-positive partner (83.0%) versus only two (28.5%) among non-infected index subjects (p<0.01). Dyspeptic symptoms and number of children were not different between the two groups (infected or non-infected spouses of H. pylori-positive index subjects). In a 1-year follow up of couples where only one partner was infected, three out of five H. pylori-negative spouses became positive. Similar results were described in 1999 by Brenner et al.5

Because the microorganism exhibits an extensive genetic heterogeneity, to confirm intra-partner spread some studies have evaluated H. pylori strains by applying molecular typing techniques. The role of H. pylori status of a patient’s spouse in reinfection after eradication success has been analyzed by Gisbert et al.13 At 12 months, eight subjects were reinfected: seven of 92 (7.6%) patients when the spouse was H. pylori positive and one of 28 (3.6%) patients when the spouse was not infected (p>0.05). Moreover, the strains in reinfected patients and their partners showed different results in the molecular study, suggesting the spouse did not act as an H. pylori reinfection reservoir for the patient. The authors concluded that the H. pylori status of the spouse did not correlate with recurrences. Different results were shown by a previous study14 in which the authors analyzed ribopatterns of H. pylori strains derived from 18 couples where both partners were infected, and described the same single strain in each of eight couples, whereas a distinct H. pylori strain was found in each partner of the remaining 10 couples. The results of our study seem to confirm those studies suggesting that having an H. pylori-infected sexual partner increases the likelihood that both members of the couple might be infected.

Because the oral cavity is not the natural niche for H. pylori, we hypothesized that an H. pylori-positive subject with GER might be more likely to infect their sexual partner than an H. pylori-positive subject without GER episodes. Therefore, we evaluated the prevalence of GER symptoms, and of acidic regurgitation in particular, in H. pylori-infected subjects both in couples with concomitant H. pylori infection and in couples where only one member was infected. The prevalence of regurgitation was significantly higher in couples with both members infected than in those where the partner was not infected. Also, the frequency of regurgitation was higher in couples with apparent transmission of the infection compared to those where transmission did not occur. Our multivariate analysis suggests that subjects are four times more likely to be H. pylori infected if their H. pylori-infected sexual partner has acidic regurgitation. Also, our study demonstrates that the longer a couple had been living together, the higher the likelihood that both members were H. pylori infected with an OR of approximately 2.4, thus supporting the relevance of person-to-person transmission. The findings of this study confirm our previous preliminary observation showing a high prevalence of H. pylori infection in the household contacts of H. pylori-infected subjects with a greater prevalence of infection not only among members of married couples but also in their children.15

This study has a number of limitations. First, we cannot exclude that in couples with both members infected, infection had occurred independently of the relationship between the subjects. To better assess this, we should have performed molecular typing to confirm that each couple was infected with the same single H. pylori strain. Also, even if this was the case, we could not rule out that both members of the couple had been exposed to the same source of infection (i.e. food, water) without an oral-to-oral transmission. Second, we did not assess H. pylori infection status in sexual partners of subjects included in the control group. The inclusion of dyspeptic people without H. pylori-infected partners in the control group might lead to a more accurate estimate of the effect of having infected partners on the prevalence of infection. Third, although heartburn and acidic regurgitation are sufficient to make a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD),16 symptoms alone do not allow us to distinguish those phenotypes with pathological exposure of the esophagus to acid compared to those without (i.e. erosive GERD or non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) vs hypersensitive esophagus and functional pyrosis). The only method to precisely assess GERD would be through 24 hour impedance pH monitoring, which was not part of the study design. However, all the patients with GERD symptoms had acidic regurgitation, which might be the more likely mechanism leading to the presence of H. pylori in the oral cavity.

In conclusion, we show that the prevalence of H. pylori infection is significantly higher in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects than in a control group of dyspeptic patients. Moreover, subjects are four times more likely to be infected with H. pylori if their H. pylori-infected sexual partners have GER symptoms. Finally, length of cohabitation seems to increase the risk of H. pylori infection.

Based on the results of this study we therefore postulate that the transmission of H. pylori infection might be, at least in part, facilitated by GER, probably through an oral-to-oral route. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated correlation of GER symptoms with the incidence of H. pylori infection in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects. Because H. pylori infection may lead to severe gastroduodenal diseases, we suggest that sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects should be tested for H. pylori infection.

Acknowledgements

Nothing to declare.

Declaration of conflicting interests

None declared.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval

This study received post hoc approval from the Ethical Committee of the Department of Polyspecialistic Internal Medicine “Luigi Vanvitelli” University Hospital on 22 May 2018. The protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written, informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

References

- 1.Ozbek A, Ozbek E, Dursun H, et al. Can Helicobacter pylori invade human gastric mucosa? An in vivo study using electron microscopy, immunohistochemical methods, and real-time polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 44: 416–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mentis A, Lehours P, Mégraud F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2015; 20(Suppl 1): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki H, Mori H. World trends for H. pylori eradication therapy and gastric cancer prevention strategy by H. pylori test-and-treat. J Gastroenterol 2018; 53: 354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarz S, Morelli G, Kusecek B, et al. Horizontal versus familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Pathog 2008; 4: e1000180–e1000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner H, Weyermann M, Rothenbacher D. Clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection in couples: Differences between high- and low-prevalence population groups. Ann Epidemiol 2006; 16: 516–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parente F, Maconi G, Sangaletti O, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastroduodenal lesions in spouses of Helicobacter pylori positive patients with duodenal ulcer. Gut 1996; 39: 629–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone MA, Taub N, Barnett DB, et al. Increased risk of infection with Helicobacter pylori in spouses of infected subjects: Observations in a general population sample from the UK. Hepatogastroenterol 2000; 47: 433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh V, Trikha B, Vaiphei K, et al. Helicobacter pylori: Evidence for spouse-to-spouse transmission. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999; 14: 519–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Bode G, et al. Active infection with Helicobacter pylori in healthy couples. Epidemiol Infect 1999; 122: 91–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirin H, Kenet G, Shevah O, et al. Evaluation of a novel continuous real time (13)C urea breath analyser for Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001; 15: 389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraser A, Delaney BC, Ford A, et al. The short-form Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire validation study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moayyedi P, Duffett S, Braunholtz D, et al. The Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire: A valid tool for measuring the presence and severity of dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998; 12: 1257–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gisbert JP, Arata IG, Boixeda D, et al. Role of partner’s infection in reinfection after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 14: 865–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgopoulos SD, Mentis AF, Spiliadis CA, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection in spouses of patients with duodenal ulcers and comparison of ribosomal RNA gene patterns. Gut 1996; 39: 634–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gravina AG, Federico A, Dallio M, et al. Intrafamilial spread of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Endoscopy 2016; 1: 1–2. (abstract).

- 16.Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 308–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]