Abstract

Background

Several studies have identified a negative association between serum glycine (Gly) levels and metabolic syndrome (MetS). However, this association has not been fully established in the elderly.

Methods

A total of 472 Chinese individuals (272 males and 200 females, 70.1 ± 6.6 years old) participated in a population-based, cross-sectional survey in Beijing Hospital. The MetS and its components were defined based on the 2006 International Diabetes Federation (IDF) standard for Asians. Serum Gly concentration was determined using isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry.

Result

The proportion of patients with MetS decreased gradually with increasing Gly levels (p for trend < 0.001), and serum Gly concentrations declined gradually with increasing numbers of MetS components (p = 0.03 for trend). After adjusting for age and gender, lower Gly levels were significantly associated with MetS and central obesity, with OR (95% CI) of 0.40 (0.25–0.65) and 0.46 (0.28–0.74). The stratified analysis conducted according to age showed that the OR between serum Gly levels and MetS was greater in those older than 65 (OR = 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51–0.86) than in those younger than 65 (OR = 0.89; 95% CI, 0.54–1.46). In the stratified analysis, using other age cut-off points, the results consistently showed that the association between serum Gly levels and MetS was more remarkable in the older groups.

Conclusions

Gly levels are associated with cardiometabolic characteristics and MetS in the elderly, and the association is more pronounced in very old people than in younger old people.

Keywords: Serum glycine, Metabolic syndrome, Elderly

Introduction

In recent years, the improvements in living standards, economic development, and lifestyle changes have led to a longer life expectancy for older people, and the global elderly population has continued to increase. With the increase of age, the incidence of cardiometabolic diseases in the elderly may rise gradually [1, 2]. However, most studies of the metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors have focused on young to middle-aged adults, and the impact of most risk factors on diseases may generally change with aging [3]. Due to the special physiological characteristics of the elderly, it is not appropriate to apply these risk factor assessment criteria to the elderly population.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is reported to be a risk factor for increased risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease and a proven risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity, especially stroke and coronary heart disease (CHD), and mortality in the elderly [4, 5]. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), MetS is highly prevalent in old people, in whom it varies from 37 to 41.9% [6]. Given that digestive and metabolic functions are gradually weakened in the elderly, eventually leading to reduced intake and absorption of nutrients, catabolism plays a dominant role in the metabolic processes of the elderly. Compared to young adults, amino acids and other nutrients may play a more important role in the elderly, and their levels in serum may mostly reflect nutritional status rather than metabolic disorder [7]. With the development of metabolomics technology, it has become an important way to evaluate nutritional level and disease risk. Recent metabolomics studies have found the relationship between serum levels of amino acids such as glycine (Gly) and cardiometabolic disease.

Gly is a major and the simplest non-essential amino acid in humans, animals, and many mammals. It is mainly generated in the liver and kidney and is used to produce creatine, purine, glucose, and collagen and is involved in anti-inflammatory processes, the immune function, and anti-oxidation reactions [8]. Recently, some studies have demonstrated the inverse association of serum Gly levels with several traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension [9], type 2 diabetes (T2D) [10], and obesity [11]. Researchers have found that circulation Gly levels in patients with MetS are significantly lower than in normal subjects [12, 13]. Moreover, serum Gly levels in obese and diabetic patients are significantly lower than those in healthy individuals, and the improvement of insulin resistance can increase serum Gly levels [14–16]. However, the associations of serum Gly levels with MetS and its components have not been fully established in the elderly.

Therefore, we proposed to use a cross-sectional study of 472 Chinese subjects, of whom about 80% are older than 65 years old, to investigate the association between serum Gly levels and MetS in the elderly and whether this association in the elderly is different from relatively young adults.

Methods

Study population

The design of and recruitment for the population-based cross-sectional study has been described in detail elsewhere [17]. Briefly, a total of 472 eligible participants (272 males and 200 females, 70.1 ± 6.6 years old) from a group of Beijing residents attending an annual physical examination in a period from August to October, 2011, were recruited randomly. People with malignant tumors, blood system diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, and have taking amino acid supplements were excluded. The sera from fasting blood samples obtained from subjects were isolated and stored at − 80 °C until being analyzed. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Beijing Hospital of the Ministry of Health, and written, informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Serum Gly measurement

Serum Gly concentrations were determined using isotope dilution liquid–chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Briefly, 0.05 ml aliquots of Gly (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) calibrators (539.8, 269.9, 134.9, 67.5, and 33.7 μmol/l) or serum samples were mixed with 0.05 ml of the isotope-labeled internal standard (Gly-D5, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, USA) solution (312.5 μmol/l). Serum Gly was extracted with 0.4 ml of acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid and analyzed using liquid chromatography method associated with mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The LC separation was performed on an Agilent 1200 series LC system. Two microliter aliquots of the prepared samples were injected onto a Waters Shield C18 column (3.5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm) maintained at 20 °C and eluted with a mobile phase of 0.01% formic acid in water-acetonitrile (90:10) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. An API 4000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Sciex Applied Biosystems) was used for the MS/MS detection. The detection was performed with positive electronic spray ionization (ESI) in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode at a source temperature of 700 °C and a voltage of 5500 V. The dwell times were 0.08 s for MRM. Nitrogen was used as the curtain, nebulizer, and collision gas at pressures of 50, 60, and 70 psi, respectively. Certain ion transitions for Gly and the internal standards were m/z 76.0 → 30.0 and 78.0 → 32.0, respectively. The calibration curve was generated using a linear regression of the peak area ratios (y) versus the amino acid concentrations (x) of the calibrators.

Other parameters and laboratory assays

Information about demographic variables—health status, smoking and alcohol drinking status, medications, and family history of diseases—were recorded using a standardized questionnaire. Height, body weight, waist circumference (WC), and sitting blood pressure (BP) were measured. The serum samples were also tested for fasting blood glucose (FBG), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), apolipoprotein (apo) AI and B, and high-sensitive C-reactive protein (CRP), using assay kits from Sekisui Medical Technologies (Osaka, Japan) on a Hitachi 7180 chemistry analyzer.

Definition of MetS

MetS and its components were defined based on the 2006 International Diabetes Federation standard for Asians with central obesity (male: WC ≥90 cm; female: WC ≥80 cm), in addition to two or more of the following criteria [18]: (1) BP ≥130/85 mmHg or taking antihypertensive drugs; (2) TG ≥1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dl) or had received treatment; (3) HDL-C: male < 1.04 mmol/L (40 mg/dl), female < 1.3 mmol/L (50 mg/dl) or had received treatment; (4) FPG ≥5.6 mmol/L (100 mg/dl) or had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

Statistical analysis

The main continuous variables were all tested for normality. Normally distributed data were expressed as means ± SD, whereas variables obeying a skewed distribution were shown as median (interquartile range). Count data were reported as frequencies and percentages. For quantitative data, the variance analysis was conducted to compute the difference across the Gly tertiles, whereas for count data, the Chi-square test was used. Correlation coefficients between Gly levels and metabolic traits were calculated by Spearman partial correlation after adjustment for age and gender. Serum Gly levels were depicted according to the number of MetS components, using a linear regression model. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which adopted the entry method and the maximum likelihood ratio test for MetS and its components. Potential confounding variables, including age; gender; smoking; alcohol drinking; family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD; and CRP, were controlled in the regression models. The performance of Gly measurements for classifying MetS status was assessed by logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic analysis. Stratified analyses were performed according to age and serum CRP levels [< 0.09 (median) and ≥ 0.09 mg/dL]. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc.) was used for statistical analysis of the data, and PASS 15.0 software was used for calculating the statistical power.

Result

Characteristics of population according to Gly tertile

The Gly levels of 472 subjects had skewed distribution (Skewness = 1.95, kurtosis = 6.53), and they could not be normally distributed after natural logarithm, logarithmic transformation of 10, and square root (SQRT) transformation. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in our study was 39.0%. As shown in Table 1, according to serum Gly tertile levels, the subjects with higher Gly levels were more likely to be female (p < 0.05). With respect to metabolic traits, BMI, WC, and TG significantly declined with increasing Gly levels, which had a dose–response relationship (all p < 0.01 for trend); in contrast, HDL-C levels increased notably (p < 0.01 for trend). However, increased Gly levels did not show association with changes in BP, TC, LDL-C, andCRP levels. Remarkably, the proportion of patients with MetS decreased gradually with increasing Gly levels (p for trend < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population by serum Gly tertiles

| Characteristica | Tertile of serum Gly | P trend b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| Number | 158 | 157 | 157 | |

| Gly, μmol/L | 219.3 (205.2–230.8) | 253.5 (247.2–261.2) | 301.1 (285.0–344.7) | < 0.001 |

| Age, years | 70.6 ± 6.7 | 69.9 ± 6.1 | 69.7 ± 6.9 | 0.253 |

| Male, n (%) | 102 (64.6) | 91 (57.9) | 79 (50.3) | 0.011 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.0 ± 3.2 | 24.4 ± 3.2 | 23.7 ± 3.4 | 0.001 |

| WC, cm | 88.6 ± 8.4 | 87.4 ± 9.2 | 84.4 ± 8.8 | < 0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 134.8 ± 16.3 | 136.6 ± 19.9 | 132.8 ± 16.9 | 0.331 |

| DBP, mmHg | 76.8 ± 8.0 | 75.7 ± 9.1 | 75.8 ± 8.0 | 0.341 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 11 (7.0) | 17 (10.8) | 15 (9.6) | 0.424 |

| Current drinker, n (%) | 20 (12.7) | 25 (15.9) | 15 (9.6) | 0.901 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 5.8 ± 1.1 | 5.8 ± 1.3 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 0.164 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 0.001 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 0.8 | 0.312 |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | 0.004 |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 2.9 (2.3–3.5) | 3.0 (2.3–3.5) | 2.9 (2.4–3.3) | 0.708 |

| Apo AI, mg/dL | 138.6 (127.3–149.2) | 137.5 (128.7–150.6) | 142.0 (130.6–153.5) | 0.075 |

| ApoB, mg/dL | 98.8 ± 21.2 | 98.3 ± 22.3 | 97.2 ± 19.7 | 0.499 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.1 (0.05–0.18) | 0.1 (0.05–0.19) | 0.08 (0.04–0.15) | 0.067 |

| MetSc, n (%) | 78 (49.4) | 59 (37.6) | 47 (29.9) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: Gly glycine, BMI body mass index, WC waist circumference, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, FBG fasting blood glucose, TC total cholesterol, TG triglyceride, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, MetS metabolic syndrome, CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Apo AI, B, CII, and CIII represent apolipoprotein AI, B, CII, and CIII, respectively

aData are mean ± SD, median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, or percentage for categorical variables

bP values for trend

cDefined according to the criteria for metabolic syndrome from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) (2006) for Asians

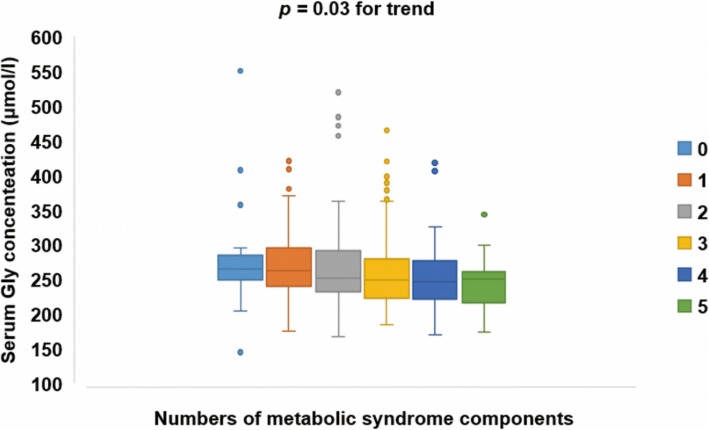

Serum Gly concentrations declined gradually with increasing numbers of MetS components (p = 0.03 for trend) (Fig. 1). The median (interquartile range) of serum Gly concentrations for those with none to five components were 265.8 (247.1–290.9), 262.6 (240.4–296.1), 252.0 (232.1–293.1), 249.9 (223.1–280.9), 247.1 (220.5–281.2), 250.7 (214.5–265.4) μmol/L, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Box-chart for serum Gly concentrations according to the number of MetS components. Data are depicted by box plots extending from the 25th to the 75th percentile and whiskers ranging from the lower limit to the upper limit. The horizontal line in the box plot represents the median, and dots in the figure represent outliers. MetS and its components were defined based on the 2006 IDF standard. Serum Gly concentrations declined gradually with an increasing number of MetS components (p = 0.03 for trend)

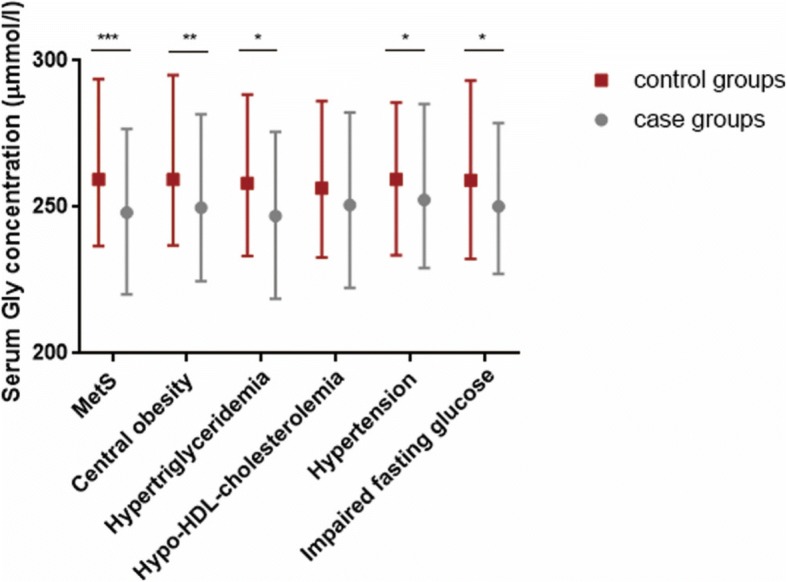

According to the definition of MetS, the population was divided into control and case groups, respectively, based on whether the population had MetS, abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, hypo-HDL-cholesterolemia, hypertension, and impaired fasting glucose (IFG). Regarding the patterns of dichotomous cardiometabolic traits, serum Gly levels were found to be lower in subjects with MetS, central obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, and IFG than in the corresponding control groups (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). No difference existed between serum Gly levels and hypo-HDL-cholesterolemia.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the circulating Gly concentrations median (interquartile range) according to MetS and its components. MetS and its components were defined based on the 2006 IDF standard. The Mann-Whitney U rank-sum test was used to estimate the difference between two groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Correlations between serum Gly levels and cardiometabolic risk factors

As shown in Table 2, partial Spearman correlation analysis demonstrated the correlation between metabolic characteristics and Gly concentration. The strongest correlation was between Gly and BMI after adjusting for age and gender (p < 0.001, R = − 0.197). Serum Gly concentration was significantly negatively associated with most of the cardiovascular risk factors, such as BMI, WC, TG, and CRP (p < 0.05) and were positively associated with protective factors, including HDL-C (p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Partial correlation coefficients between serum Gly concentration and metabolic characteristics after adjustment for age and gender

| Total R | P | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI | −0.197 | < 0.001 |

| WC | −0.193 | < 0.001 |

| SBP | −0.087 | 0.065 |

| DBP | −0.054 | 0.249 |

| FBG | −0.083 | 0.078 |

| TG | −0.142 | 0.002 |

| TC | 0.004 | 0.927 |

| HDL-C | 0.141 | 0.003 |

| LDL-C | −0.028 | 0.555 |

| Apo AI | 0.079 | 0.093 |

| ApoB | −0.075 | 0.109 |

| CRP | −0.093 | 0.049 |

All correlation coefficients were calculated after adjustment for age and gender

Abbreviations: Gly glycine, BMI body mass index, WC waist circumference, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, FBG fasting blood glucose, TC total cholesterol, TG triglyceride, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, CRP high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Apo AI, B represent apolipoprotein AI and B, respectively

Association of serum Gly levels with MetS and its components

As presented in Table 3, the associations between serum Gly levels and MetS and its components were analyzed by multivariate logistic regression. The ORs for MetS, central obesity, and hypertriglyceridemia were all meaningful no matter whether serum Gly levels were regarded as continuous variables or categorical variables (all p < 0.05). When Gly levels were used as categorical variables, the crude ORs for MetS, central obesity, and hypertriglyceridemia were lower with increasing Gly levels in model 1, which had a dose–response relationship (p < 0.05 for trend). After adjusting for age and gender (model 2), lower Gly levels were significantly associated with MetS and central obesity, with ORs (95% CI) of 0.40 (0.25–0.65) and 0.46 (0.28–0.74). Further controlling for smoking status; alcohol drinking; CRP; and family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD only slightly attenuated the strength of the association for MetS, central obesity, and hypertriglyceridemia. The results were the same when the Gly levels were used as a continuous variable. The sensitivity and specificity of Gly measurements for MetS diagnosis were 71.2 and 65.5%, respectively.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for MetS and its components according to serum Gly levels

| Gly as a continuous variable | Gly as a categorical variable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per SD increment | P | T1 | T2 | T3 | P trend a | |

| MetS | ||||||

| Model 1 b | 0.75 (0.61–0.93) | 0.008 | 1.0 | 0.61 (0.39–0.97) | 0.43 (0.27–0.70) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 c | 0.71 (0.58–0.88) | 0.002 | 1.0 | 0.59 (0.37–0.94) | 0.40 (0.25–0.65) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 d | 0.72 (0.57–0.91) | 0.005 | 1.0 | 0.66 (0.40–1.09) | 0.43 (0.26–0.71) | 0.001 |

| Central obesity | ||||||

| Model 1 b | 0.79 (0.65–0.95) | 0.013 | 1.0 | 0.58 (0.37–0.93) | 0.54 (0.34–0.87) | 0.011 |

| Model 2 c | 0.69 (0.56–0.84) | 0.0001 | 1.0 | 0.54 (0.33–0.87) | 0.46 (0.28–0.74) | 0.002 |

| Model 3 d | 0.68 (0.54–0.84) | 0.001 | 1.0 | 0.62 (0.37–1.03) | 0.49 (0.29–0.81) | 0.006 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | ||||||

| Model 1 b | 0.83 (0.67–1.04) | 0.109 | 1.0 | 0.64 (0.39–1.04) | 0.48 (0.29–0.80) | 0.004 |

| Model 2 c | 0.77 (0.61–0.97) | 0.024 | 1.0 | 0.60 (0.37–0.99) | 0.42 (0.25–0.71) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 d | 0.80 (0.63–1.00) | 0.053 | 1.0 | 0.64 (0.31–1.33) | 0.61 (0.30–1.25) | 0.176 |

| Hypo-HDL-cholesterolemia | ||||||

| Model 1 b | 0.89 (0.71–1.11) | 0.306 | 1.0 | 0.76 (0.46–1.27) | 0.76 (0.46–1.27) | 0.291 |

| Model 2 c | 0.83 (0.66–1.04) | 0.103 | 1.0 | 0.72 (0.43–1.21) | 0.68 (0.40–1.15) | 0.149 |

| Model 3 d | 0.84 (0.66–1.07) | 0.156 | 1.0 | 0.77 (0.44–1.34) | 0.74 (0.43–1.29) | 0.860 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Model 1 b | 0.95 (0.78–1.17) | 0.627 | 1.0 | 1.03 (0.61–1.72) | 0.87 (0.53–1.44) | 0.582 |

| Model 2 c | 0.97 (0.78–1.19) | 0.739 | 1.0 | 1.05 (0.62–1.76) | 0.89 (0.54–1.49) | 0.661 |

| Model 3 d | 0.96 (0.77–1.20) | 0.710 | 1.0 | 1.14 (0.66–1.97) | 0.89 (0.52–1.51) | 0.674 |

| Impaired fasting glucose | ||||||

| Model 1 b | 0.85 (0.71–1.04) | 0.097 | 1.0 | 0.96 (0.62–1.50) | 0.67 (0.43–1.05) | 0.079 |

| Model 2 c | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 0.898 | 1.0 | 1.01 (0.64–1.58) | 0.73 (0.46–1.14) | 0.168 |

| Model 3 d | 0.92 (0.75–1.13) | 0.431 | 1.0 | 1.07 (0.66–1.71) | 0.76 (0.47–1.22) | 0.253 |

aP values for trend

bModel 1: Crude risk for MetS

cModel 2: Adjusted for age and gender

dModel 3: Further adjusted for smoking status; alcohol drinking; CRP; and family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD

More significant association between serum Gly levels and MetS in the older groups

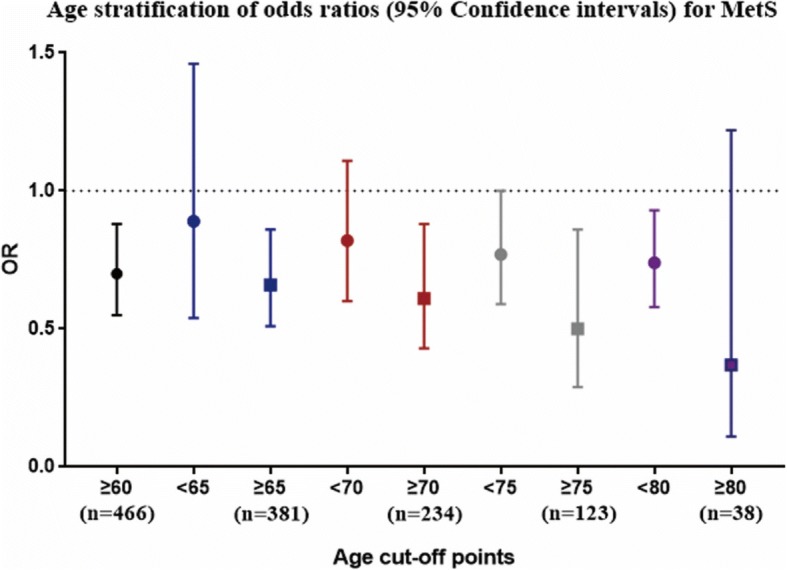

Stratified analysis of the associations of serum Gly levels and MetS was conducted according to a 65-year age cut-off point. The results showed that the OR between serum Gly levels and MetS (95% CI) was 0.71 (0.55–0.91) in the group of those older than 65, whereas in the group of those younger than 65 years old, the OR was 0.92 (0.60–1.42) in model 1, which means that the association was more pronounced in the groups of those aged ≥65 regardless of Gly levels used as a continuous variable or a categorical variable (Tables 4 and 5). What’s more, the ORs for MetS according to serum Gly levels in the groups with ages ≥65 were only a little changed after further adjusting for age and gender (model 2), as well as when additionally controlling for smoking status; alcohol drinking; CRP; and family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD (model 3). Further, when we used age stratification analysis at ages 60, 70, 75, and 80, the results also showed that the ORs between serum Gly levels and MetS were more significant in the older groups (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Stratified analysis of odds ratios (95% Confidence intervals) for MetS and its components according to serum Gly levels (per 1-SD increment)

| <65y | P | ≥65y | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per SD increment | Per SD increment | |||

| MetS | ||||

| Model 1 a | 0.92 (0.60–1.42) | 0.711 | 0.71 (0.55–0.91) | 0.006 |

| Model 2 b | 0.92 (0.60–1.41) | 0.695 | 0.65 (0.50–0.83) | 0.001 |

| Model 3 c | 0.89 (0.54–1.46) | 0.642 | 0.66 (0.51–0.86) | 0.002 |

| Central obesity | ||||

| Model 1 a | 0.77 (0.50–1.18) | 0.236 | 0.79 (0.64–0.98) | 0.028 |

| Model 2 b | 0.74 (0.48–1.15) | 0.183 | 0.67 (0.54–0.85) | 0.001 |

| Model 3 c | 0.69 (0.43–1.12) | 0.130 | 0.67 (0.52–0.86) | 0.002 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | ||||

| Model 1 a | 1.14 (0.71–1.83) | 0.586 | 0.77 (0.59–0.99) | 0.046 |

| Model 2 b | 1.11 (0.69–1.78) | 0.668 | 0.70 (0.53–0.91) | 0.007 |

| Model 3 c | 1.15 (0.70–1.88) | 0.574 | 0.72 (0.55–0.94) | 0.016 |

| Hypo-HDL-cholesterolemia | ||||

| Model 1 a | 1.47 (0.94–2.31) | 0.092 | 0.74 (0.56–0.99) | 0.043 |

| Model 2 b | 1.44 (0.90–2.28) | 0.127 | 0.69 (0.51–0.92) | 0.012 |

| Model 3 c | 1.44 (0.88–2.35) | 0.145 | 0.69 (0.51–0.94) | 0.018 |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Model 1 a | 0.97 (0.62–1.53) | 0.893 | 0.95 (0.75–1.19) | 0.633 |

| Model 2 b | 0.96 (0.60–1.52) | 0.850 | 0.95 (0.75–1.20) | 0.679 |

| Model 3 c | 0.97 (0.60–1.57) | 0.890 | 0.94 (0.74–1.21) | 0.633 |

| Impaired fasting glucose | ||||

| Model 1 a | 0.98 (0.64–1.51) | 0.926 | 0.83 (0.67–1.02) | 0.074 |

| Model 2 b | 0.98 (0.63–1.51) | 0.924 | 0.88 (0.70–1.09) | 0.232 |

| Model 3 c | 0.97 (0.61–1.55) | 0.909 | 0.92 (0.73–1.16) | 0.490 |

aModel 1: Crude risk for MetS

bModel 2: Adjusted for age and gender

cModel 3: Further adjusted for smoking status; alcohol drinking; CRP; and family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD

Table 5.

Stratified analysis of odds ratios (95% Confidence intervals) for MetS and its components according to serum Gly tertiles

| <65y | ≥65y | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | P trend a | T1 | T2 | T3 | P trend a | |

| MetS | ||||||||

| Model 1 b | 1.0 | 0.71 (0.25–2.04) | 1.08 (0.39–3.04) | 0.872 | 1.0 | 0.59 (0.36–0.98) | 0.34 (0.20–0.58) | < 0.001 |

| Model 2 c | 1.0 | 0.72 (0.25–2.07) | 1.09 (0.39–3.05) | 0.868 | 1.0 | 0.55 (0.3–0.92) | 0.29 (0.17–0.51) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 d | 1.0 | 0.62 (0.18–2.12) | 0.96 (0.30–3.01) | 0.973 | 1.0 | 0.60 (0.35–1.05) | 0.31 (0.17–0.56) | < 0.001 |

| Central obesity | ||||||||

| Model 1 b | 1.0 | 0.59 (0.20–1.71) | 0.90 (0.30–2.69) | 0.862 | 1.0 | 0.58 (0.35–0.98) | 0.48 (0.29–0.81) | 0.006 |

| Model 2 c | 1.0 | 0.62 (0.21–1.82) | 0.91 (0.30–2.76) | 0.879 | 1.0 | 0.52 (0.30–0.89) | 0.38 (0.22–0.66) | 0.001 |

| Model 3 d | 1.0 | 0.49 (0.15–1.66) | 0.73 (0.22–2.43) | 0.624 | 1.0 | 0.61 (0.35–1.09) | 0.41 (0.23–0.73) | 0.003 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | ||||||||

| Model 1 b | 1.0 | 0.51 (0.14–1.77) | 0.91 (0.29–2.87) | 0.888 | 1.0 | 0.67 (0.40–1.14) | 0.41 (0.23–0.73) | 0.002 |

| Model 2 c | 1.0 | 0.53 (0.15–1.87) | 0.92 (0.29–2.29) | 0.891 | 1.0 | 0.61 (0.35–1.05) | 0.34 (0.19–0.62) | < 0.001 |

| Model 3 d | 1.0 | 0.52 (0.14–1.95) | 0.98 (0.30–3.18) | 0.974 | 1.0 | 0.66 (0.37–1.17) | 0.38 (0.20–0.70) | 0.002 |

| Hypo-HDL-cholesterolemia | ||||||||

| Model 1 b | 1.0 | 1.67 (0.48–5.86) | 3.03 (0.90–10.11) | 0.066 | 1.0 | 0.65 (0.37–1.14) | 0.53 (0.29–0.95) | 0.032 |

| Model 2 c | 1.0 | 1.87 (0.51–6.82) | 3.28 (0.95–11.40) | 0.059 | 1.0 | 0.60 (0.34–1.07) | 0.46 (0.25–0.85) | 0.012 |

| Model 3 d | 1.0 | 2.36 (0.54–10.25) | 3.98 (0.95–16.60) | 0.058 | 1.0 | 0.63 (0.34–1.17) | 0.51 (0.27–0.97) | 0.039 |

| Hypertension | ||||||||

| Model 1 b | 1.0 | 1.10 (0.36–3.32) | 1.29 (0.42–3.99) | 0.654 | 1.0 | 1.01 (0.57–1.81) | 0.79 (0.45–1.39) | 0.405 |

| Model 2 c | 1.0 | 1.13 (0.37–3.42) | 1.30 (0.42–4.01) | 0.650 | 1.0 | 1.02 (0.57–1.83) | 0.79 (0.45–1.41) | 0.425 |

| Model 3 d | 1.0 | 1.04 (0.31–3.54) | 1.19 (0.35–4.02) | 0.784 | 1.0 | 1.16 (0.62–2.15) | 0.78 (0.43–1.41) | 0.393 |

| Impaired fasting glucose | ||||||||

| Model 1 b | 1.0 | 1.61 (0.56–4.64) | 1.06 (0.36–3.14) | 0.936 | 1.0 | 0.87 (0.53–1.42) | 0.61 (0.37–1.00) | 0.052 |

| Model 2 c | 1.0 | 1.61 (0.56–4.66) | 1.06 (0.36–3.15) | 0.936 | 1.0 | 0.91 (0.56–1.50) | 0.67 (0.40–1.10) | 0.114 |

| Model 3 d | 1.0 | 1.85 (0.58–5.86) | 1.03 (0.33–3.21) | 0.992 | 1.0 | 0.92 (0.54–1.56) | 0.70 (0.41–1.19) | 0.182 |

aP values for trend

bModel 1: Crude risk for MetS

cModel 2: Adjusted for age and gender

dModel 3: Further adjusted for smoking status; alcohol drinking; CRP; and family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD

Fig. 3.

Age stratification of odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) between serum Gly levels and MetS. Adjusted for gender; smoking status; alcohol drinking; CRP; and family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD. The y-axis represents the OR of Gly and MetS, and the x-axis represents different age cut-off points

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate the association between serum Gly levels and MetS in the elderly, showing that serum Gly levels declined gradually with increasing prevalence of MetS and number of components of MetS. In addition, after adjusting for age and gender, lower Gly levels were significantly associated with MetS and central obesity. The association was still significant after further controlling for smoking status; alcohol drinking; CRP; and family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD. Furthermore, the association between serum Gly levels and MetS was more significant in the older groups.

Several studies have previously reported the negative association between circulating Gly levels and T2D, obesity, and MetS [10, 11, 19]. Similarly, the significant decrease of Gly levels in MetS and obesity is consistent with some prior studies [12, 15]. Serum Gly concentration has been considered the only homeostatic assessment–insulin resistant (HOMA-IR)-associated predictor of both intramuscular adipose tissue and abdominal adiposity in functionally limited overweight older adults [20]. Besides, the associations of Gly levels with other components of MetS, such as hypertension and dyslipidemia, have also been found [13]. However, the current result showing no relationship of Gly levels with these two components of MetS was in contrast to the previous study. The reason for this discrepancy may be due to the minor impact of Gly on these two aspects in the elderly. Moreover, we obtained consistent results when MetS and its components were defined according to other diagnostic standards, such as the Chinese Diabetes Society (2004) and the guidelines for the prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in Chinese adults (2007).

In the present study, about 80% of subjects were older than 65 years old, and over 98% were older than 60. The chronological age was stratified by the 65-year-old, 70-year-old, 75-year-old, and 80-year-old of age cut-off points. Stratified analysis showed that the association of Gly levels with MetS was more pronounced in the older group than in the relatively younger group. The inflammatory factor, CRP, is also considered a marker of aging, and its lower level may be associated with better survival in the elderly [21, 22]. Recently, inflammatory factors, including CRP, used to evaluate biological age, were proposed by some studies [23, 24]. Therefore, we also conducted a stratified analysis of CRP that represented the biological age and found that the association between Gly levels and MetS was more obvious in the higher hs-CRP group (Table 6), which was consistent with the results of stratified analysis of chronological age. It was demonstrated that it is more important to maintain Gly at high levels in serum in the older group than in the relatively younger group.

Table 6.

Stratified analysis of odds ratios (95% Confidence intervals) for MetS and its components according to serum Gly tertiles

| MetS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 b | Model 2 c | Model 3 d | |

| CRP < 0.09 mg/dl | |||

| T1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| T2 | 0.61 (0.30–1.27) | 0.61 (0.30–1.27) | 0.64 (0.29–1.41) |

| T3 | 0.65 (0.32–1.29) | 0.64 (0.32–1.29) | 0.64 (0.30–1.34) |

| P trenda | 0.225 | 0.211 | 0.799 |

| CRP ≥ 0.09 mg/dl | |||

| T1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| T2 | 0.59 (0.32–1.11) | 0.56 (0.29–1.06) | 0.66 (0.33–1.31) |

| T3 | 0.35 (0.18–0.69) | 0.30 (0.15–0.61) | 0.32 (0.15–0.68) |

| P trenda | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

aP values for trend

bModel 1: Crude risk for MetS

cModel 2: Adjusted for age and gender

dModel 3: Further adjusted for smoking status; alcohol drinking; CRP; and family history of diabetes, hypertension, and CAD

Our study found that serum Gly concentrations declined gradually with increasing numbers of MetS components and was significantly negatively associated with BMI, WC, TG, and CRP. Therefore, it is beneficial to keep a higher Gly level in elderly people. Several indications demonstrate that Gly supplementation may be a novel therapy for obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and dietary supplementation with Gly reduces concentrations of free fatty acids and TG in an animal model of intraabdominal obesity [25]. Moreover, therapy of obesity and T2DM with Gly can improve insulin sensitivity [26], increase anti-inflammatory capacity [27], and normalize secretion of triacylglycerol-rich very-low-density lipoproteins from the liver [28]. Consequently, to hold a higher Gly level in elderly patients with MetS is a new dietary intervention that needs further confirmation.

Based on cross-sectional study of the elderly population, the present study is the first to examine the relationship between Gly levels and MetS and its components in the elderly. However, several limitations should be considered in the future. First, we were unable to obtain causality because of the cross-sectional design of the study. Thus, it is critical to conduct prospective studies in the future. Second, because of the relatively small sample size (the statistical power = 0.86), even though there was a clear trend of the associations of Gly levels and MetS and its components, only MetS and central obesity remained statistically significant after adjustment. Third, we did not record physical activity and other possible risk factors of metabolic diseases in the subjects, so possible confounding of unmeasured factors may exist, even after adjustment.

Our study demonstrated for the first time that serum Gly levels are associated with cardiometabolic characteristics and MetS in the elderly. Patients with MetS have lower Gly levels than do normal subjects. What’s more, the association between Gly levels and MetS is more pronounced in very old people than in younger old people. Our study emphasizes that it is significantly essential for the elderly population to maintain a higher Gly level in serum. Further studies are needed to confirm that Gly is a protective factor for cardiometabolic diseases in the elderly.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672075, 81301487, 81472035) and Beijing Hospital Nova Project (BJ-2018-135).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Apo

Apolipoprotein

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- CI

Confidence interval

- CRP

High-sensitive C-reactive protein

- ESI

Electronic spray ionization

- FBG

Fasting blood glucose

- Gly

Glycine

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HOMA-IR

Homeostatic assessment–insulin resistant

- IDF

International Diabetes Federation

- IFG

Impaired fasting glucose

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid chromatography method associated with mass spectrometry

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MetS

Metabolic syndrome

- MRM

Multiple reaction monitoring

- OR

Odds ratio

- SQRT

Square root

- T2D

Type 2 diabetes

- TC

Total cholesterol

- TG

Triglyceride

- WC

Waist circumference

Authors’ contributions

XL, RY, JD, LS and WC were responsible for the design of the research and the management of funds. XL, WZ, HL, SW and QZ contributed to measurements and data collection. XL, RY, LS, JD, YZ, YT and YW analyzed and checked data. XL, RY, JD and LS wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Beijing Hospital of the Ministry of Health, and written, informed consents were obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xianghui Li, Email: lxhbjmu@foxmail.com.

Liang Sun, Email: sunbmu@foxmail.com.

Wenduo Zhang, Email: zhangwenduo@medmail.com.cn.

Hongxia Li, Email: lihongxiajiao@sina.com.

Siming Wang, Email: wangsiming@163.com.

Hongna Mu, Email: hongnamu@sina.com.

Qi Zhou, Email: zhq201411@163.com.

Ying Zhang, Email: zhangying2016123@163.com.

Yueming Tang, Email: 842876298@qq.com.

Yu Wang, Email: yu_wang91@foxmail.com.

Wenxiang Chen, Email: wxchen@nccl.org.cn.

Ruiyue Yang, Email: ruiyue_yang@163.com.

Jun Dong, Email: jun_dong@263.net.

References

- 1.Tourlouki E, Matalas AL, Panagiotakos DB. Dietary habits and cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged and elderly populations: a review of evidence. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;4(4):319–330. doi: 10.2147/cia.s5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Repas TB. Challenges and strategies in managing cardiometabolic risk. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107(2):4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lind L, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J, Lampa E. Impact of Aging on the Strength of Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Longitudinal Study Over 40 Years. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(1):e007061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Ford ES. Risks for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes associated with the metabolic syndrome: a summary of the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(7):1769–1778. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.7.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denys K, Cankurtaran M, Janssens W, Petrovic M. Metabolic syndrome in the elderly: an overview of the evidence. Acta Clin Belg. 2009;64(1):23–34. doi: 10.1179/acb.2009.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadaegh F, Zabetian A, Tohidi M, Ghasemi A, Sheikholeslami F, Azizi F. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome by the adult treatment panel III, international diabetes federation, and World Health Organization definitions and their association with coronary heart disease in an elderly Iranian population. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009;38(2):142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun L, Hu C, Yang R, Lv Y, Yuan H, Liang Q, et al. Association of circulating branched-chain amino acids with cardiometabolic traits differs between adults and the oldest-old. Oncotarget. 2017;8(51):88882. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Razak MA, Begum PS, Viswanath B, Rajagopal S. Multifarious beneficial effect of nonessential amino acid, Glycine: a review. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1716701. doi: 10.1155/2017/1716701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El HM, Pérez I, Baños G. Is glycine effective against elevated blood pressure? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metabolic Care. 2006;9(1):26–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000196143.72985.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Luca G, Calpona PR, Caponetti A, Macaione V, Di Benedetto A, Cucinotta D, et al. Preliminary report: amino acid profile in platelets of diabetic patients. Metab Clin Exp. 2001;50(7):739–741. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.24193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberbach A, Blüher M, Wirth H, Till H, Kovacs P, Kullnick Y, et al. Combined proteomic and metabolomic profiling of serum reveals association of the complement system with obesity and identifies novel markers of body fat mass changes. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(10):4769. doi: 10.1021/pr2005555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badoud F, Lam KP, Dibattista A, Perreault M, Zulyniak MA, Cattrysse B, et al. Serum and adipose tissue amino acid homeostasis in the metabolically healthy obese. J Proteome Res. 2014;13(7):3455–3466. doi: 10.1021/pr500416v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamakado M, Nagao K, Imaizumi A, Tani M, Toda A, Tanaka T, et al. Plasma free amino acid profiles predict four-year risk of developing diabetes, metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and hypertension in Japanese population. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11918. doi: 10.1038/srep11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adeva-Andany M, Souto-Adeva G, Ameneiros-Rodriguez E, Fernandez-Fernandez C, Donapetry-Garcia C, Dominguez-Montero A. Insulin resistance and glycine metabolism in humans. Amino Acids. 2018;50(1):11-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Takashina C, Tsujino I, Watanabe T, Sakaue S, Ikeda D, Yamada A, et al. Associations among the plasma amino acid profile, obesity, and glucose metabolism in Japanese adults with normal glucose tolerance. Nutr Metab. 2016;13(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12986-015-0059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drabkova P, Sanderova J, Kovarik J, Kandar R. An assay of selected serum amino acids in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2015;24(3):447–451. doi: 10.17219/acem/29223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang R, Dong J, Zhao H, Li H, Guo H, Wang S, et al. Association of branched-chain amino acids with carotid intima-media thickness and coronary artery disease risk factors. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the international diabetes federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23(5):469–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ntzouvani A, Nomikos T, Panagiotakos D, Fragopoulou E, Pitsavos C, McCann A, et al. Amino acid profile and metabolic syndrome in a male Mediterranean population: a cross-sectional study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27(11):1021. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lustgarten MS, Price LL, Phillips EM, Fielding RA. Serum glycine is associated with regional body fat and insulin resistance in functionally-limited older adults. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e84034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giovannini S, Onder G, Liperoti R, Russo A, Carter C, Capoluongo E, et al. Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha as predictors of mortality in frail, community-living elderly individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(9):1679–1685. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rønning B, Wyller TB, Seljeflot I, Jordhøy MS, Skovlund E, Nesbakken A, et al. Frailty measures, inflammatory biomarkers and post-operative complications in older surgical patients. Age Ageing. 2010;39(6):758. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sebastiani P, Thyagarajan B, Sun F, Schupf N, Newman AB, Montano M, et al. Biomarker signatures of aging. Aging Cell. 2017;16(2):329–338. doi: 10.1111/acel.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang WG, Zhu SY, Bai XJ, Zhao DL, Jiang SM, Li J, et al. Select aging biomarkers based on telomere length and chronological age to build a biological age equation. Age. 2014;36(3):9639. doi: 10.1007/s11357-014-9639-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Hafidi M, Perez I, Zamora J, Soto V, Carvajal-Sandoval G, Banos G. Glycine intake decreases plasma free fatty acids, adipose cell size, and blood pressure in sucrose-fed rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287(6):R1387–R1393. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00159.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gannon MC, Nuttall JA, Nuttall FQ. The metabolic response to ingested glycine. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(6):1302–1307. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekhar RV, McKay SV, Patel SG, Guthikonda AP, Reddy VT, Balasubramanyam A, et al. Glutathione synthesis is diminished in patients with uncontrolled diabetes and restored by dietary supplementation with cysteine and glycine. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):162–167. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yue JT, Mighiu PI, Naples M, Adeli K, Lam TK. Glycine normalizes hepatic triglyceride-rich VLDL secretion by triggering the CNS in high-fat fed rats. Circ Res. 2012;110(10):1345–1354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.