Abstract

Objective:

Recent studies have shown that serum cystatin C (Cys C) is a better marker for measuring the glomerular filtration rate and may rise more quickly with acute kidney injury (AKI). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical application of serum Cys C to predict colistin-induced nephrotoxicity in comparison with serum creatinine (SCr).

Methods:

Thirty-two adult patients with no history of acute or chronic kidney injury having been planned to receive intravenous colistin for an anticipated duration of at least 1 week for any indication were recruited. At baseline and 5 days after colistin treatment, serum Cys C as well as creatinine levels were measured. The incidence of colistin-induced acute renal failure was defined according to the AKIN criteria for SCr. Rise in concentration of Cys C by more than 10% from baseline considered as AKI.

Findings:

Colistin-induced nephrotoxicity (defined as SCr ≥0.3 mg/dl) occurred in 6 patients (18.8%). A Cys C increase concentration ≥10% after 5 days of colistin treatment was detected in 15 patients (46.9%). There was a poor agreement between the presence and absence of any SCr-AKI and Cys C-AKI (κ = 0.28, P = 0.04).

Conclusion:

Serum Cys C is a better marker of renal function in early stages of AKI and predictive of persistent AKI on colistin treatment.

KEYWORDS: Colistin, cystatin C, nephrotoxicity, serum creatinine

INTRODUCTION

Colistin, a polymyxin antimicrobial agent, was originally used in the 1960s, but due to nephrotoxicity rates moving toward half, it was abandoned as other “less toxic” antimicrobials became available.[1] Colistin has recently reemerged as a last-line therapeutic agent for the treatment of multidrug-resistant pathogens including Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Since its recent reemergence, data suggest that colistin is associated with a much lower rate of renal toxicity compared with historical reports. The majority of recent studies report toxicity rates of 10%–30%.[2,3,4,5] The mechanism of nephrotoxicity is through an increase in tubular epithelial cell membrane permeability, which results in cation, anion, and water influx leading to cell swelling and cell lysis. There are also some oxidative and inflammatory pathways that seem to be involved in colistin nephrotoxicity.[6,7] Risk factors of colistin nephrotoxicity can be categorized as dose and duration of colistin therapy, co-administration of other nephrotoxic drugs, and patient-related factors such as age, sex, hypoalbuminemia, hyperbilirubinemia, underlying disease, and severity of patient illness. This nephrotoxicity seems to be dose dependent and reversible.[8,9]

Drug-induced nephrotoxicity is increasingly recognized as a significant contributor – at least 20% to kidney disease including acute kidney injury (AKI). Standard definitions of drug-induced kidney disease are lacking, leading to challenges in recognition and reporting.[10] Evaluation of nephrotoxicity through blood tests includes the measurements of blood urea nitrogen (BUN), concentration of serum creatinine (SCr), glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and creatinine clearance (CrCl). However, these assessments of nephrotoxicity are only possible when a majority of kidney function is damaged.[11,12]

The use of the SCr level for estimation of the GFR has some limitations, such as dependence on sex, age, nutrition, and body mass. In studies on colistin nephrotoxicity, SCr and RIFLE criteria are usually used for detection of nephrotoxicity.[13,14] Cystatin C (Cys C) is a cysteine protease inhibitor that is synthesized by all nucleated cells and freely filtered by the glomerulus, metabolized in proximal tubules, and not secreted. The levels of Cys C are not affected by renal conditions, increased protein catabolism, or dietetic factors. Moreover, it does not change with age or muscle mass like creatinine does. However, few studies demonstrate that older age is independently associated with higher serum Cys C levels after adjusting for CrCl.[15]

In the Ghlissi et al.[16] study, in an animal model of colistin nephrotoxicity, evaluation of change of plasma Cys C, along with urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), g-glutamyltransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, and aspartate and alanine aminotransferase for monitoring of colistin nephrotoxicity, was carried out and the results were compared with histopathological assessment. The results of the study showed that plasma Cys C is more accurate than plasma creatinine and urinary NGAL is the most sensitive biomarker for detection of colistin nephrotoxicity. The most sensitive biomarker for the detection of colistin-associated nephrotoxicity is not introduced.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical application of serum Cys C in comparison with SCr in patients receiving colistin to determine, which of them is a better biomarker for detection of colistin-induced AKI.

METHODS

This was a prospective observational study conducted in the medical wards of “Alzahra” Teaching Hospital Affiliated to Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS) from March 2016 to November 2016. The Ethics Committee of IUMS approved the study (Project number: P23/14/653). Informed consent was obtained from patients or next of kin or appropriate surrogate before participation in the study.

All adult inpatients initiating treatment with colistin for at least 1 week in the medical wards were considered potentially eligible. Exclusion criteria included preexisting renal insufficiency, use of nephrotoxic drugs before or during the study period, colistin use for <5 days, and receiving of antioxidants such as Vitamin E and N-acetylcysteine which could disrupt the results.

At days 0 and 5 of colistin treatment, serum Cys C as well as creatinine levels were measured. SCr level was determined by an Auto-analyzer (Biotechnica BT-3000, Italy) based on the modified Jaffe colorimetric reaction. Serum Cys C level was measured by the turbidimetric method (Gentian, Moss, Norway). GFR was estimated using the CKD-EPI equations for CrCl and for Cys C-based GFR.[17]

We collected data on patient demographics, date of admission, indication for colistin use, interval and dose of colistin, comorbid conditions, and the use of other potentially nephrotoxic drugs and the culture results.

Colistin was prescribed with an average dose of 360 mg, equivalent to 4.5 million units two times a day for eligible patients.

The primary outcome for this study was the occurrence of colistin-induced AKI, which was defined as AKIN criteria for AKI[18] or as a rise in concentration of Cys C by more than 10% from baseline of this marker.[19] We also evaluated the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and accuracy of the Cys C level for the detection of colistin-induced nephrotoxicity.

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA). Continuous variables were compared between groups using Mann–Whitney or t-tests, as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests. Agreement level between SCr and Cys C-AKI definitions was assessed using Cohen's kappa (agreement: <0.4, poor; 0.4–0.75, fair to good; >0.75, excellent). In all analyses, we considered the significance level of <0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 32 patients (20 males, 12 females) were enrolled in the study. The mean age of the patients was 49.22 ± 20 years (range: 19–86 years). Ventilator-associated pneumonia was the most common diagnosis at colistin initiation (n = 21, 56.6%). A. baumannii (n = 23, 71.9%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 7, 21.9%) were the most common isolated organisms. All of them were sensitive to colistin. The mean duration of treatment with colistin was 19.3 ± 17.6 days.

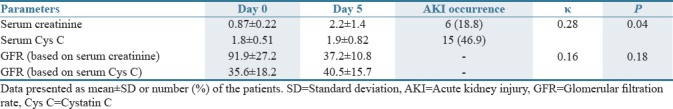

Table 1 shows the changes in serum concentrations of creatinine and Cys C at the study time points (days 0 and 5). Colistin-induced nephrotoxicity (defined as SCr ≥0.3 mg/dl) occurred in 6 patients (18.8%). A Cys C increase concentration ≥10% after 5 days of colistin treatment was detected in 15 patients (46.9%). There was poor agreement (Kappa = 0.28, P = 0.04) between the presence and absence of any SCr-AKI and Cys C-AKI.

Table 1.

Changes in serum creatinine and serum cystatin C and the glomerular filtration rate values at the study time points

Cyst C-based GFR reflects a decline in GFR following colistin administration in a much better way compared to creatinine-based GFR. Table 1 presents the mean of serum concentrations and calculated GFR of creatinine and Cys C in patients with colistin-induced nephrotoxicity. The agreement between the GFR based on the SCr and Cys C CKD-EPI formula was poor and was not statistically significant (κ = 0.16, P = 0.18).

Based on the CrCl at day 0, no one had nephrotoxicity, but the Cys C-based equation predicts that 16 patients (50%) had renal impairment (GFR <60 ml/min). At day 5 of study, the rate of nephrotoxicity was 5 (15.6%) and 20 (62.5%) according to creatinine-based GFR and Cys C-based GFR which was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Drug-induced nephrotoxicity is closely associated with acute renal damage as well as with chronic kidney diseases. However, traditional nephrotoxicity assays such as measurement of the concentration of SCr or BUN do not have the sensitivity and selectivity required to determine nephrotoxicity before the severe progression of renal damage. Because traditional standard markers such as SCr have low sensitivity and specificity, the timing of the diagnosis and treatment are often delayed. Recently, the serum concentration of Cys C was introduced as an ideal endogenous marker of GFR, and the utility of Cys C for estimating GFR and its diagnostic accuracy have been confirmed in several studies.[20,21,22,23,24] Therefore, we evaluated the utility of serum Cys C to more sensitively detect nephrotoxicity of polymyxin analogs.

Ghlissi et al.[16] showed that plasma Cys C is more accurate than plasma creatinine and urinary NGAL is the most sensitive biomarker for detection of colistin nephrotoxicity. In another study by Keirstead et al.,[25] using an animal model, the accuracy of some urinary biomarkers for the detection of AKI in polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity was evaluated. In this study, kidney injury molecule-1 and α-glutathione S-transferase were the most sensitive biomarkers for prediction of polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity. There are no additional studies about new biomarkers of kidney injury in colistin nephrotoxicity; SCr and RIFLE criteria are almost always used for the detection of colistin nephrotoxicity.

Several reports have been published regarding the utility of Cys C in pharmacotherapy with drugs affected by renal excretion. Stabuc et al.[26] found the serum concentration of Cys C to be a superior marker to that of creatinine for the detection of decreased CrCl and potentially for the estimation of GFR in cancer patients. Furthermore, Hoppe et al.[27] reported that Cys C was a better marker of the elimination of topotecan than the serum concentration of creatinine, while O'Riordan et al.[28] showed that the serum concentration of Cys C was no better than SCr for predicting digoxin clearance. Although the utility of Cys C in pharmacotherapy has not been well established, we have found that Cys C is a better marker of colistin nephrotoxicity than is SCr. Further study with a larger population is needed to establish the credibility of our finding since this study involved only a small number of samples.

The high sensitivity and specificity of Cys C as well as its independence of other factors appear to make Cys C equivalent to CrCl for early renal failure detection. Moreover, because of many errors in outpatient's measurement of CrCl, the use of Cys C may be the more appropriate method for reduced GFR estimation than CrCl.

Cys C is produced at a constant rate by all nucleated cells and its concentration is not influenced by age, sex, height, and body composition. Accordingly, Cys C concentration reflects only the balance of its primary physiological determinants: cellular generation, renal filtration, and subsequent renal degradation.[13] An increased Cys C concentration identifies early deviations in GFR and, subsequently, a “preclinical” state of kidney dysfunction that is not detected with SCr or GFR.[29]

In conclusion, the present study suggests that serum Cys C is more useful for predicting colistin nephrotoxicity than is SCr. If supported with further studies, serum concentration of Cys C and calculated GFR might be used to provide more accurate and earlier knowledge about renal dysfunction induced by colistin and to take appropriate preventive measures.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

Sarah Mousavi designed the work, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript and approved the final article. Bahareh Jamali interpreted of data for the work, revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. Mohsen Meidani collected the data, revised and approved the final manuscript. All authors are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Biswas S, Brunel JM, Dubus JC, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Rolain JM. Colistin: An update on the antibiotic of the 21st century. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2012;10:917–34. doi: 10.1586/eri.12.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azzopardi EA, Ferguson EL, Thomas DW. Colistin past and future: A bibliographic analysis. J Crit Care. 2013;28:219.e13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bialvaei AZ, Samadi Kafil H. Colistin, mechanisms and prevalence of resistance. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:707–21. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1018989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dijkmans AC, Wilms EB, Kamerling IM, Birkhoff W, Ortiz-Zacarías NV, van Nieuwkoop C, et al. Colistin: Revival of an old polymyxin antibiotic. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37:419–27. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Justo JA, Bosso JA. Adverse reactions associated with systemic polymyxin therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:28–33. doi: 10.1002/phar.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim LM, Ly N, Anderson D, Yang JC, Macander L, Jarkowski A, 3rd, et al. Resurgence of colistin: A review of resistance, toxicity, pharmacodynamics, and dosing. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:1279–91. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.12.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doshi NM, Mount KL, Murphy CV. Nephrotoxicity associated with intravenous colistin in critically ill patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1257–64. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.12.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temocin F, Erdinc S, Tulek N, Demirelli M, Bulut C, Ertem G, et al. Incidence and risk factors for colistin-associated nephrotoxicity. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2015;68:318–20. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2014.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koksal I, Kaya S, Gencalioglu E, Yilmaz G. Evaluation of risk factors for intravenous colistin use-related nephrotoxicity. Oman Med J. 2016;31:318–21. doi: 10.5001/omj.2016.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awdishu L, Mehta RL. The 6R's of drug induced nephrotoxicity. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:124. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0536-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coca SG, Yalavarthy R, Concato J, Parikh CR. Biomarkers for the diagnosis and risk stratification of acute kidney injury: A systematic review. Kidney Int. 2008;73:1008–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs TC, Hewitt P. Biomarkers for drug-induced renal damage and nephrotoxicity – An overview for applied toxicology. AAPS J. 2011;13:615–31. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9301-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang JX, Kaeslin G, Ranall MV, Blaskovich MA, Becker B, Butler MS, et al. Evaluation of biomarkers for in vitro prediction of drug-induced nephrotoxicity: Comparison of HK-2, immortalized human proximal tubule epithelial, and primary cultures of human proximal tubular cells. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2015;3:e00148. doi: 10.1002/prp2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kane-Gill SL, Smithburger PL, Kashani K, Kellum JA, Frazee E. Clinical relevance and predictive value of damage biomarkers of drug-induced kidney injury. Drug Saf. 2017;40:1049–74. doi: 10.1007/s40264-017-0565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shlipak MG, Mattes MD, Peralta CA. Update on cystatin C: Incorporation into clinical practice. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:595–603. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghlissi Z, Hakim A, Mnif H, Ayadi FM, Zeghal K, Rebai T, et al. Evaluation of colistin nephrotoxicity administered at different doses in the rat model. Ren Fail. 2013;35:1130–5. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2013.815091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Tighiouart H, Simon AL, Inker LA. Comparing newer GFR estimating equations using creatinine and cystatin C to the CKD-EPI equations in adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70:587–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai TY, Chien H, Tsai FC, Pan HC, Yang HY, Lee SY, et al. Comparison of RIFLE, AKIN, and KDIGO classifications for assessing prognosis of patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2017;116:844–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herget-Rosenthal S, Marggraf G, Hüsing J, Göring F, Pietruck F, Janssen O, et al. Early detection of acute renal failure by serum cystatin C. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1115–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grams ME, Juraschek SP, Selvin E, Foster MC, Inker LA, Eckfeldt JH, et al. Trends in the prevalence of reduced GFR in the united states: A comparison of creatinine- and cystatin C-based estimates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:253–60. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rule AD, Bailey KR, Lieske JC, Peyser PA, Turner ST. Estimating the glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine is better than from cystatin C for evaluating risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;83:1169–76. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Ärnlöv J, Inker LA, Katz R, Polkinghorne KR, et al. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:932–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamb EJ, Brettell EA, Cockwell P, Dalton N, Deeks JJ, Harris K, et al. The eGFR-C study: Accuracy of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) estimation using creatinine and cystatin C and albuminuria for monitoring disease progression in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease – Prospective longitudinal study in a multiethnic population. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emrich IE, Pickering JW, Schöttker B, Lennartz CS, Rogacev KS, Brenner H, et al. Comparison of the performance of 2 GFR estimating equations using creatinine and cystatin C to predict adverse outcomes in elderly individuals. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:636–8. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keirstead ND, Wagoner MP, Bentley P, Blais M, Brown C, Cheatham L, et al. Early prediction of polymyxin-induced nephrotoxicity with next-generation urinary kidney injury biomarkers. Toxicol Sci. 2014;137:278–91. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stabuc B, Vrhovec L, Stabuc-Silih M, Cizej TE. Improved prediction of decreased creatinine clearance by serum cystatin C: Use in cancer patients before and during chemotherapy. Clin Chem. 2000;46:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoppe A, Séronie-Vivien S, Thomas F, Delord JP, Malard L, Canal P, et al. Serum cystatin C is a better marker of topotecan clearance than serum creatinine. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3038–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Riordan S, Ouldred E, Brice S, Jackson SH, Swift CG. Serum cystatin C is not a better marker of creatinine or digoxin clearance than serum creatinine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:398–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soto K, Coelho S, Rodrigues B, Martins H, Frade F, Lopes S, et al. Cystatin C as a marker of acute kidney injury in the emergency department. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1745–54. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00690110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]