Abstract

Background:

HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a major public health problem and a development predicament that affects all sectors, drastically affecting the health, economic, and reducing social life expectancy, deepening poverty, and contributing to and exacerbating food shortages. Strict adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen is essential to obtain the desired benefit and to avoid the emergence of drug resistance and clinical failure; therefore, this study is aimed to assess the antiretroviral (ARV) adherence among the HIV patients and suggesting them by possible ways for improving the adherence.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Batu Hospital, Batu town. The sample size was found to be 160, and systemic random sampling was used to collect data by providing a pretested structured questionnaire. The qualitative data were analyzed to identify the significance of the relationship between the dependent and independent variables.

Results:

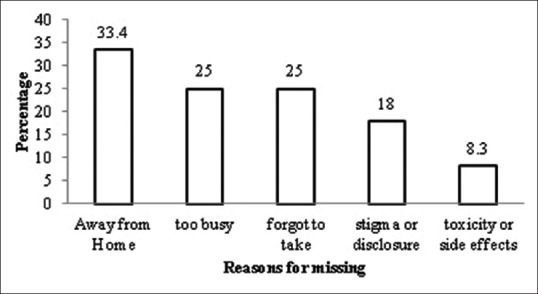

A total of 160 patients was agreed to involve in our survey, 85.6% of patients were adherent by self-report. The main reason of nonadherence cited by the patients were; being away from home for some social reasons (33.4%), being too busy with other things (25.0%), simply forgot to take their ART (25.0%), developed toxicity or side effects (8.3%), having problems for fear of stigma and disclosure (8.3%), and (7.5%) of participants also shortage of ARV medications at hand because of some public holidays or weekends that coincide with date of appointments.

Conclusion and Recommendations:

The self-report adherence rate was higher than that seen in developing countries. Programs and clinical efforts to improve medication taking in the study setups should strive to provide the regular follow-up for patients, increase patients’ awareness of the side effects of ARVs and possible remedies, integrate medications better into patients’ daily routines, improve patients’ confidence, trust, and satisfaction with their caregivers, and teach patients to use memory aids.

Keywords: Adults, antiretroviral therapy, Non adherence

INTRODUCTION

HIV is a major public health disease caused by a retrovirus that destroys the human T-lymphocytes, making more susceptible to various infectious diseases. The most advanced stage of HIV infection is acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Since the inception of the first case reported in 1981, death rates were increased to more than 2.5 millions in 2005; later, it was decreased with implementation of emergency precautions and controlling measurements by the WHO and other NGOs. Globally,[1,2] still 36.7 million people are living with HIV from a report in 2015, the global prevalence was account as 0.8% with a mean range of age was between 15 and 49 years; the deaths were drastically decreased more than 45% from 2005 due to antiretroviral therapy (ART) scale-up. Those patients who suffer from AIDS, their CD4 count is below 200 cells/mm[3] should offer ART. The ART will shorten the illness duration and improves the quality of life by reduction of viral load and increasing the level of CD4 cells.[4,5,6,7] There were 2.6 million fresh infections reporting annually, where two-thirds of new infections were from Sub-Saharan Africa countries.[3]

Ethiopia is one of the Sub-Saharan African country, their infections are epidemic with an estimation about 671,941 HIV-positive cases, among them 256,319 were male and 415,622 were female reported by the National AIDS resource center in 2016.[8] It was established in Addis Ababa in 2002, capital city of Ethiopia, a fee-based ART medication was initiated in 2003 cooperation with 12 hospital facilities. In 2005, the Global Fund, The world bank and PEPFAR program were expanded their free services to 22 hospitals to reach 211,000 populations including children.[9] In 2006, the Ethiopian government accelerated the access to the ART medication to poor patients; the ART sites reached 260.[10] By February 2009, the cases were controlled in 136,344 on ART,[11] this is feasibly the adherence to the given medication. The NARC survey showed that 1.5% of their adult population were with HIV infection 2011, where females 1.9% were more suffered than male, 1.5% population, where it was progressively decreased in 2016 to 1.1% of total, 1.4% females, 0.7% males. Even though the number of new infections is decreasing, cases attention was increased to 485,025 from 383,960 to ART medication; this may be due to lack of knowledge and attitude toward the patient adherence.

Adherence can be defined as the extent to match the prescribed medication doses taken over a given period by the patient.[12,13] Taking more than 95% of the prescribed doses are considered as optimal and less than 95% are suboptimal. Adherence to ART reduces viral load in the patient and prevents the emergence of medication change. Suboptimal therapy was associated with low CD4 cell count; it could lead to poor health outcomes and drug resistance.[14]

Adherence can be measured using different methods including medication event monitoring system, pill counting system, prescription refill, and self-adherence reports.[15] Pill counting adherence can be calculated by counting the remaining doses of medication. Self-adherences can be done by themselves, but because their forgetfulness may not give good results. However, no single adherence measurement should not be considered as accurate; it can be a combination of more than one measure of adherence can give good information.[16]

Many factors have been associated with nonadherence as stated by the WHO. In addition to these factors, including of side effects, nonavailability of drugs, forgetfulness, and finally, the fear of social rejection. These suggested factors are chosen to evaluate the association of nonadherence in our study area.

The issue of ART adherence among the adult patients is important in our chosen study area because of a little information is known either published or unpublished results about the adherence levels. Therefore, the aim of our study is to assess the associated factors with nonadherence among the HIV positive adult people receiving ART medication. The specific objectives of this work are to determine the level of adherence and identify the WHO suggested factors with their hinder to the adherence on determination of patient's knowledge, attitude, and perceptions toward ART.

METHODS

Study area and sample size

It is an institutional-based cross-sectional, descriptive study was designed and conducted on adult patients receiving ART medication at the Batu Hospital in Batu town, Eastern Ethiopia. The town is 148 km far away from the Southeast direction to Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia. The institution is run by the Ethiopian government linked to medical college with 100 beds. The sample size was referenced using 17.2% of total proportion according to a same study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia,[17] and 95% confidence interval and 5% marginal error was used to result a total of 187 patients. The study data were obtained during from January 10, 2015, to February 09, 2015.

Sampling method

The sampling frame contained names of the AIDS patients on ART attending the hospital. Patients in a comprehensive care clinic meeting the inclusion criteria were selected using a systematic random sampling method until the required sample size was obtained. The sampling interval was three.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

HIV/AIDS patients, those follow-up for more than 3 months and had an age of greater than 18 years and above were included in this study. Those who attended the ART medication below 18 years of age and less than 3 months of follow-up were excluded from the study.

Study variables

Medication adherence was selected as dependent variable and sociodemographic, cultural, and economic factors chosen as independent variables to identify the association between them.

Data collection

A questionnaire was prepared in English and translated into local languages of Afaan Oromo and Amharic. Structured questionnaires were used to collect the flawless information on background, the knowledge, attitude, perception, and practice of the use of antiretrovirals (ARVs). The patient information records were reviewed to cross-check their self-reported information on the level of adherence. The collected data were assessed and verified for wholeness after the interview ends with the participants. To keep the quality of our data, we used a pretested questionnaire for this study.

A letter of support for ethical consideration was produced before the study was carried out on the wards of Batu Hospital obtained from the Jimma University. Data were collected after an agreement with the study participants following a brief explanation on the ART adherence importance of the study. The data were collected from those who were willing to participate in this study only. Confidentiality of the collected data was maintained throughout the study.

Limitations of study

This study is limited to adult HIV-positive patients, who receiving ART, and who was attending at the ARV clinic in Batu town hospital. That makes this study is unrepresentative of the whole population of ART patients in eastern Ethiopia. Hence, the findings are generalizable to the participating hospital. Adherence and nonadherence were classified as per Robinson et al.[18]

RESULTS

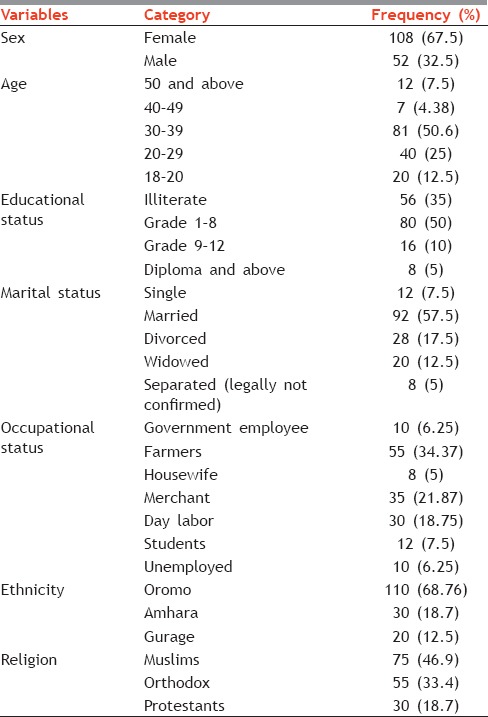

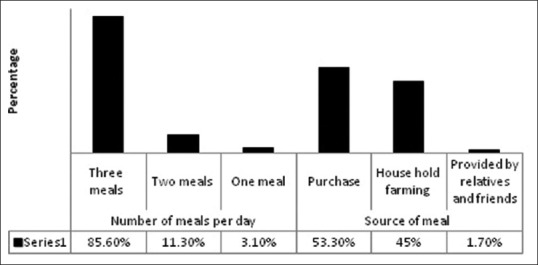

Among the total population selected for this study, twenty-seven patients were refused to participate because of either not interested or fear of social discloses. Finally, 160 participants were agreed to participate. A total of 67.5% were females and the mean age of 34.5 ± 14.45 years with a range of 18–59 years. Of the respondents, 57.5% were married, 68.75% were belongs to Oromo ethnicity, and 46.9% were Islam followers. More than 85% were either never attended the school or attended primary grade. The majority (34.37%) of them was farmers, and a total of 10 participants were claiming that they are unemployed. The majority (55.6%) of them mentioned that they had income <1200 ETB per month, 54% were living urban areas, time to travel for ARV medication was more than 1 h for 2.25%, and 78.75% using public transport to reach, more than 18% were faced stigma because of their social disclose, the sociodemographic data results as shown in Table 1. Almost all of them received the first-line ART therapy. More than half of them were under the combination of tenofovir + lamivudine + efavirenz. The source of a meal for the majority (53.3%) were purchased, and 85.6% were able to afford three meals in a day as shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic attributes of the cross-sectional survey in Batu Hospital 2015

Figure 1.

Source and number of meals having per day

Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medication

The past 2 weeks adherence was measured at their next visit. Among the total participants, 14.40% of them were followed less than 95% of their prescription instructions, considered to be nonadhered whereas 85.6% of them were adhered more than 95% to their instructions. The majority (81.2%) of them never missed a single dose and 18.8% were reportedly missing one dose since their enrollment. The patients were mentioned various reasons for nonadherences in their interview, and the reported reasons for nonadherences on missing doses were being away from home, too busy with their works, forgot to take, stigma, and disclose of status as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Reasons for nonadherence

Sociocultural factors perception toward antiretroviral therapy adherence

All patients had a positive attitude toward the ARV medication and have the same opinion of management of AIDS. The majority 82% of respondents said that neither friends nor relatives avoid them during their treatment. The rest of the respondents, 18% suffered from a stigma. The most of respondents, 92% were knew that ARV treatment reduces the viral load, but the remaining of them assumes that the ART cures the disease. Almost all of them mentioned that the hospital is the only source of medication. Most of them (55%) were under the antibiotic treatment for coinfection, the majority of them, 15% were only under the tuberculosis treatment.

Health-care facilities influence on antiretroviral therapy adherence

All of the respondents were able to follow the ART therapy, they know the importance of the course, and they counseled before they start their medication, privacy was maintained during the consultations and agreed that it was important for HIV patients to be counseled as they continue with ARV treatment because it helped to improve the CD4 cell count. The majority of respondents, 84.4% were not known about the side effects and interactions of ART.

Factors associated with adherence to antiretroviral therapy

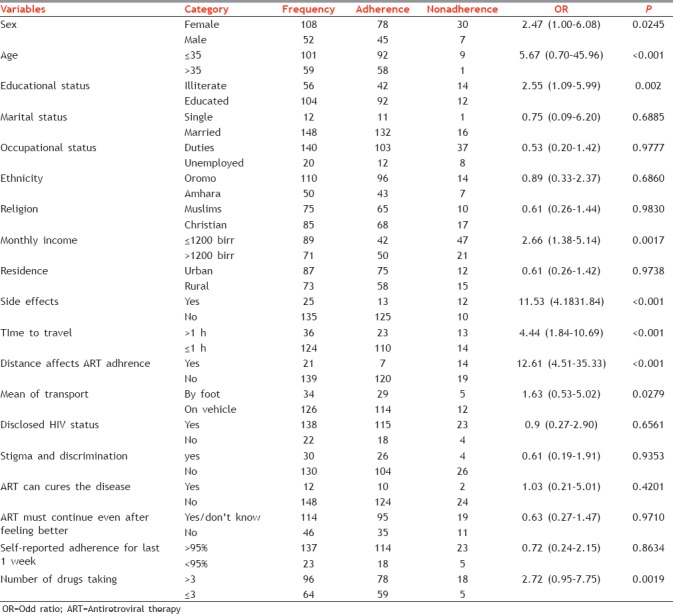

An univariate analysis found that nine variables were significantly associated with nonadherence, those whose are female (odds ratio [OR] = 2.47, P = 0.002), who are below 35 years of age (OR = 5.67, P = 0.001), had a monthly income of more than 1200 ETB (OR = 2.66, P = 0.001), educated (OR = 2.55, P = 0.002), married, had a side effects (OR = 11.53, P < 0.001), traveled more than 1 h (OR = 4.44, P < 0.001), distance effect (OR = 12.6, P < 0.001), who traveled on vehicle to reach (OR = 1.63, P = 0.027), were likely significantly affect the ART therapy, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with self-reported adherence

DISCUSSION

The overall adherence rate was found in our study was more than 85%, which is higher than observed in neighboring countries, Kenya,[19] Sudan,[20] and South Africa,[21] where the adherence rate is <80%, this adherence rate was near to the other studies conducted in different regions of the same country, Addis ababa,[22] Debreziet,[23] Jimma.[24] The high-level adherence will help to control of viral load.[25] Most of the African settings achieved an excellent rate of adherences when compared to the North-American counterparts estimated as 77%; this may be due to availability of subsidized ART medication.[26,27] The possibility of adherence might be due to (a) self-reported adherence, (b) limited to first-line medication, (c) excluding of patients who are not interested.

Many factors associated were consistent with the other studies from developing, developed countries, in our study, female ratio showed the highest nondherence than males, this finding was inline other studies in the country. Since females are busy with household management chances of forget of their doses, the reported reasons for nonadherence in African studies include forgetting, travel, fear of disclosure, shortage of pills, difficult schedules, cost, lack of access, and privacy.[28]

In a cohort study of ARV adherence among semi-urban South African living in extreme poverty, Byakika-Tusiime et al. found that lower socioeconomic status was not a predictor of adherence for patients with fully subsidized therapy.[29] In fact, adherence levels were similar to or better than those found in industrialized countries. Similarly, high levels of adherence (78%) were reported by Laurent et al.[30] In a resource-poor setting in Senegal and 66% in 3 treatment centers in Kampala, Uganda, adherence in our study was lower than the levels reported by Orrell et al.[31] but higher than that reported by Laurent et al. and Byakika-Tusiime et al. that leave our adherence rate within the range of adherence rates of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) to ARV therapy in African settings. The most reasons for missing doses were being away from home, forgetting, and being too busy. The most important factors associated with increased adherence include educational level of the patient and treatment for other coinfections. Factors that were not associated with adherence included patient gender, marital status, and discrimination.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The level of adherence was found to be (85.6%) suboptimal, but comparable to other developing countries. Stigma or fear of disclosure, being away from home, too busy with other things, the side-effects, and toxicity of ART drugs, are the main obstacles to ART adherence. HIV/AIDS patients need a special assistant usually someone living in the household who can assist with adherence issue. Support group on ARV therapy should be organized for PLWHA to enable the patient remember taking ART; reduce the workload on them, barrier to adherence.

Financial support and sponsorship

We would like to thank School of Pharmacy, Jimma University for financial support of this work and also to the CBE office for their support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank School of Pharmacy, Jimma University for financial support of this work and also to the CBE office for their support. Special thanks to the staff members of Batu Hospital ARV clinical units for their support on collection of data.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update 2016. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Core Epidemiology Slides. UNAIDS; 2016. UNAIDS. 2016. [Last accessed on 2016 Jun 12]. Available from: http://www.aidsinfo.unaids.org/

- 3.United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. AIDS Epidemic Update. UNAIDS/09.36E/JC1700E. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan DR, Salomon JA. Prevention and treatment of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in resource-limited settings. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:135–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carballo E, Cadarso-Suárez C, Carrera I, Fraga J, de la Fuente J, Ocampo A, et al. Assessing relationships between health-related quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:587–99. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021315.93360.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castro A. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: Merging the clinical and social course of AIDS. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilks C, Vitoria M. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. World Health Organization. 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HIV/AIDS Estimates and Projections in Ethiopia 2011–2016. [Last accessed on 2015 Jan 07]. Available from: http://www.etharc.org/resources/healthstat/hivaids-estimates-and-projections-in-ethiopia-2011-2016 .

- 9.Foreman M. Antiretroviral Drugs for All? Obstacles to Access to HIV/AIDS Treatment. Lessons from Ethiopia Haiti India Nepal and Zambia. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ethiopian Federal Ministry of health HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office. Single Point HIV Prevalence Estimate. 2007a [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health: HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office. Monthly HIV Care and ART Update. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ingersoll KS, Cohen J. The impact of medication regimen factors on adherence to chronic treatment: A review of literature. J Behav Med. 2008;31:213–24. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9147-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin S, Elliott-DeSorbo DK, Calabrese S, Wolters PL, Roby G, Brennan T, et al. A comparison of adherence assessment methods utilized in the United States: Perspectives of researchers, HIV-infected children, and their caregivers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:593–601. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabaté E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. World Health Organization; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markos E, Worku A, Davey G. Adherence to ART in PLWHA at Yirgalem hospital, South Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2008;22:174–179. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vitolins MZ, Rand CS, Rapp SR, Ribisl PM, Sevick MA. Measuring adherence to behavioral and medical interventions. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:188S–94S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mengesha A, Worku A. Assessment of Antiretroviral Treatment Among HIV Infected Persons in the Ministry of Defense Hospitals. MPH Thesis. AAU. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. Patient-centered care and adherence: Definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:600–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mukui IN, Ng’ang’a L, Williamson J, Wamicwe JN, Vakil S, Katana A, et al. Rates and predictors of non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive individuals in Kenya: Results from the second Kenya AIDS indicator survey, 2012. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibrahim Y, Sutan R, Latif KA, Al-Abed AA, Amara A, Adam I. Poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy and associated factors among people living with HIV in Omdurman city, Sudan. Malays J Public Health Med. 2014;14:90–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Dowdy DW, Lo M, Omer SB, Regensberg L, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy assessed by pharmacy claims predicts survival in HIV-infected South African adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:78–84. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225015.43266.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tadios Y, Davey G. Antiretroviral treatment adherence and its correlates in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2006;44:237–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayalew M. Assessment of Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among Hiv-Infected Persons in the Ministry of National Defense Force Hospitals, Addis Ababa And Debreziet. Doctoral Dissertation, Aau. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miftah A. Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence and Its Determinants among People Living With HIV/AIDS on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy at Two Hospitals in Oromiya Regional State, Ethiopia. Doctoral Dissertation, Aau. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenblum M, Deeks SG, van der Laan M, Bangsberg DR. The risk of virologic failure decreases with duration of HIV suppression, at greater than 50% adherence to antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byakika-Tusiime J, Oyugi JH, Tumwikirize WA, Katabira ET, Mugyenyi PN, Bangsberg D. Boston, USA: Ability to purchase and secure stable therapy are significant predictors of non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Kampala, Uganda. In: Tenth Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurent C, Fatou N, Gueye NF, Diakhaté N, Ndir A, Gueye M, et al. Boston, MA, USA: 2003. Long-term follow-up of a cohort patients under HAART in Senegal. In: 10th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; pp. 10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Day J, Godoka N, Nyamafeni P, Chigwanda M. Proceedings of the International AIDS Conference. 2002. Adherence to ART in clinical trial settings in Zimbabwe and Uganda: Lessons learned. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byakika-Tusiime J, Polley EC, Oyugi JH, Bangsberg DR. Free HIV antiretroviral therapy enhances adherence among individuals on stable treatment: implications for potential shortfalls in free antiretroviral therapy. PloS one. 2013;8:e70375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laurent C, Diakhate N, Gueye NF, Touré MA, Sow PS, Faye MA, Gueye M, Lanièce I, Kane CT, Liégeois F, Vergne L. The Senegalese government's highly active antiretroviral therapy initiative: an 18-month follow-up study. Aids. 2002;16:1363–70. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orrell C, Cohen K, Mauff K, Bangsberg DR, Maartens G, Wood R. A randomized controlled trial of real-time electronic adherence monitoring with text message dosing reminders in people starting first-line antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS. 2015;70:495–502. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]