Abstract

Background

Resveratrol, a polyphenol found on the surface of red fruits, is able to suppress many kinds of malignancies. Nevertheless, its mechanism of action is not yet clear. Consequently, this study aimed to elucidate its influence and explore the etiology of PCCs (prostate cancer cells).

Material/Methods

The proliferation of prostate cancer cells was determined by CCK-8 assay. Cell apoptosis was determined by Hoechst staining FC assay. Cell migration was detected by scratch test. The levels of apoptosis-related protein were detected by Western blot analysis.

Results

It was discovered that resveratrol suppresses cellular survival and migration and enhances cell death. In addition, it was revealed that resveratrol elevated ROS concentration and expression of biomarker of cell death Bax, while inhibiting Bcl2, an anti-apoptotic protein, and reinforcing expression of p53. Moreover, resveratrol remarkably increased the expressions of HIF-1α and p53 in PC cells. Resveratrol suppressed cell survival and promoted cell death, but its effects were reversed after HIF-1α knockdown, suggesting that the effects of resveratrol in PC are mediated via HIF-1α.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that resveratrol induces apoptosis via HIF-1α/ROS/p53 signaling in prostate cancer cells and may be a useful therapeutic agent against prostate cancer.

MeSH Keywords: Apoptosis, Deamino Arginine Vasopressin, MAP Kinase Kinase Kinase 5

Background

Prostate cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer. A series of innovative therapies aimed at treating terminal PC has emerged recently [1]. Nevertheless, taking public health into consideration, drugs which could prevent the development of PC, as well as drugs that could act during early stages of PC, matter the most [2]. Similar to other malignancies, PC also exhibits a few peculiar characteristics of its own and there is an urgent need to develop innovative therapeutic agents because of a series of adverse effects, as well as lack of effective conventional treatment strategies [3]. Recently, new innovative strategies have emerged that shift our attention from artificial/chemical agents to more natural agents [4,5]. Recent findings suggest that the use of dietary compounds could be an alternate strategy to control prostate cancer progression [6,7].

Resveratrol (RES) was initially discovered in polyphenol phytoalexin extracted from roots of white hellebore and was later found on the surface of various vegetables and fruits [8]. RES participates is effective against atherosclerosis [9], inflammation [10], and various malignancies [11]. Previous studies have reported the anticancer effects of resveratrol via regulation of cell death, growth, and metastasis, as well as generation of vessels [12,13]. In monocyte endothelium, RES triggers cell proliferation via regulation of the stimulation of protein kinases C and D [14]. Moreover, in MCF-7 cells, RES triggers cell death via inhibition of NF-κB and AP1[15]. Clinical trials have assessed the use of RES as a cancer preventive and therapeutic agent. However, the role of RES in prostate cancer and the underlying mechanisms responsible remain unclear. The present study was conducted to explore the mechanisms involved in the effect of RES against prostate cancer in murine prostate cancer TRAMP cells.

Material and Methods

Cell lines and cultivation

TRAMP cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (www.ATCC.org) before being preserved in DMEM containing 10% FBS (v/v), bovine insulin (0.005 mg/ml), antibiotics/antimycotics (1%), and dehydroisoandrosterone (10 nM) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Zhongshan Hospital of Dalian University.

Evaluation of cell survival

CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate cell survival. In brief, at a predetermined time point before treatment termination, each cell-containing well was supplemented with 100 μl CCK-8 solution. The cells were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. A multi-well spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, USA) was used to measure the absorbance at 450 nm.

Flow cytometry (FC)

Cold PBS was used to wash the harvested cells twice. The cells were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min and the supernatant was discarded. Binding buffer was used for resuspension. The buffer was supplemented with FITC-Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI). The mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. An FACS scan flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used to measure the fluorescence signals. The rate of cell death was calculated with the help of FlowJo software version 7.6.

Hoechst staining (HS)

Hoechst 33342 (Sigma) was used to stain fixed cells to calculate the number of dead cells. A Nikon Optical TE2000-S inverted fluorescence microscope was used to observe the morphology of dead cells. More than 400 cells from 12 randomized visual fields were assessed to quantify dead cells. Each procedure was conducted twice.

Scratch test

Trypsin was used for digestion in 6-well plates containing cells at the density of 4×105/well. Scratches were introduced in the monolayer of adhered cells using a sterile pipette tip (10 μL). Aseptic PBS was used to wash the cells and cells that washed off were eliminated. Medium was renewed with fresh medium without serum. Scratch distance was evaluated and recorded immediately and at 24 h.

Investigation of intracellular ROS

A fluorescent probe CM-H2DCFDA specific to ROS was used to examine the ROS inside the cells. Thirty-minute incubation was carried out in 25 μM H2 DCF-DA, followed by PBS washing. A multi-well spectrophotometer was used to examine the fluorescence at 485–530 nm. ROS generation in the control group was arbitrarily considered to be 100%.

siRNA and cell transfection

Fifty nanomoles of HIF-1α siRNA oligoribonucleotide purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology underwent transfection using RNAiFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Inc.). Negative siRNA served as the control. After 6 h of incubation at 37°C, admixture was eliminated. An additional 24-h incubation was carried out in the presence of medium with 0.5% serum prior to activation.

Western blot (WB) analysis

Homogenization was conducted using lysis buffer (Beyotime, China). Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was used for protein quantification. SDS-PAGE was used for protein quantification. We used 8–15% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad) to isolate the proteins, which were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA) after isolation. Immunoblots were incubated overnight in the presence of primary antibodies (anti-caspase-3, anti-Bcl2, anti-p53, anti-Bax, anti-β-actin, and anti-HIF-1α, all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA) in TBST at 4°C. Subsequently, secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP were added to the mixture. ECL plus detection agent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) was used to examine immunoreactive bands. The Omega 16ic Chemiluminescence Imaging System (Ultra-Lum, CA, USA) was used for analysis.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ±SEM. Differences between various groups were evaluated with a 2-tailed, unequal-variance t test or ANOVA prior to Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Differences were regarded as significant at P<0.05.

Results

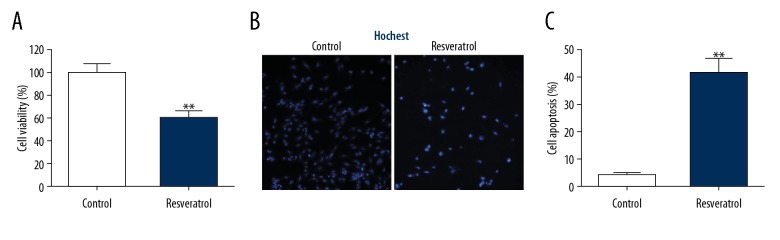

Resveratrol enhances apoptosis in TRAMP cells

To test the effect of resveratol on TRAMP cells, a cell-killing assay was performed. As shown in Figure 1A, resveratol significantly inhibited cell viability. Further cell apoptosis assays were measured by Hoechst staining and flow cytometry. Resveratrol increased cell apoptosis (Figure 1B, 1C). These data indicate that resveratrol kills tumor cells.

Figure 1.

Resveratrol enhanced cell death among TRAMP cells. TRAMP cells received a supplement of resveratrol (50 μM) for 24 h. (A) CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate cell survival. (B) Cell death was revealed by HS. (C) FC was used to evaluate cell death. Results are presented in the form of mean ±SEM from 3 independent experiments. ** P<0.01 vs. control group.

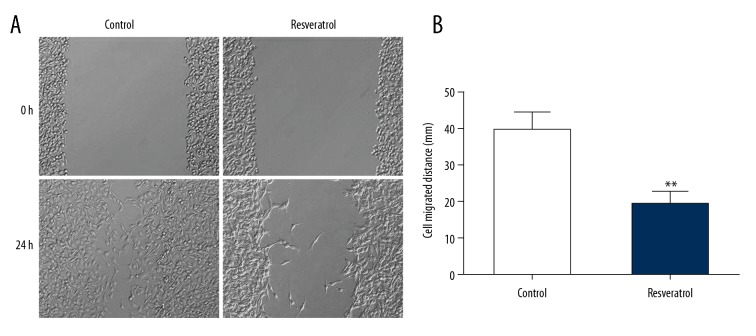

Resveratrol inhibits migration of TRAMP cells

The scratch test was used to determine cell migration to assess whether resveratrol influenced migration of TRAMP cells. In comparison to control, cell migration was remarkably suppressed in the experimental group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Resveratrol suppressed migration of TRAMP cells. TRAMP cells received a supplement of resveratrol (50 μM) for 24 h. (A) Scratch test revealed migration. (B) Cell migration distance. Results are presented as mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. ** P<0.01 vs. control group.

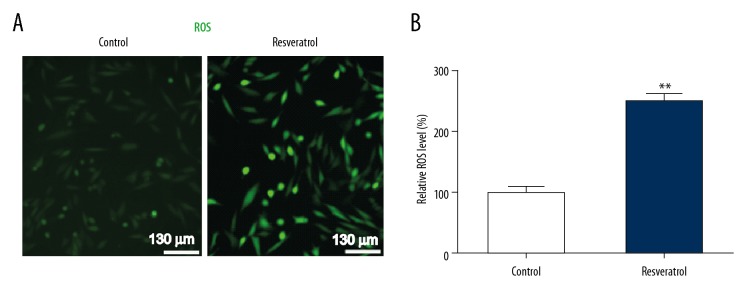

Resveratrol triggers ROS generation in TRAMP cells

To assess the influence of resveratrol on ROS in TRAMP cells, ROS levels inside the cells were evaluated using H2DCF-DA assay. Resveratrol noticeably enhanced generation of ROS, as indicated by H2DCFDA fluorescence (Figure 3), suggesting that resveratrol triggers ROS generation in TRAMP cells.

Figure 3.

Resveratrol triggers ROS generation in TRAMP cells. TRAMP cells received a supplement of resveratrol (50 μM) for 24 h. (A) ROS inside the cells was assessed via oxidation of H2DCF-DA. (B) Quantification of ROS within TRAMP cells. Results are presented in the form of mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. ** P<0.01 vs. control group.

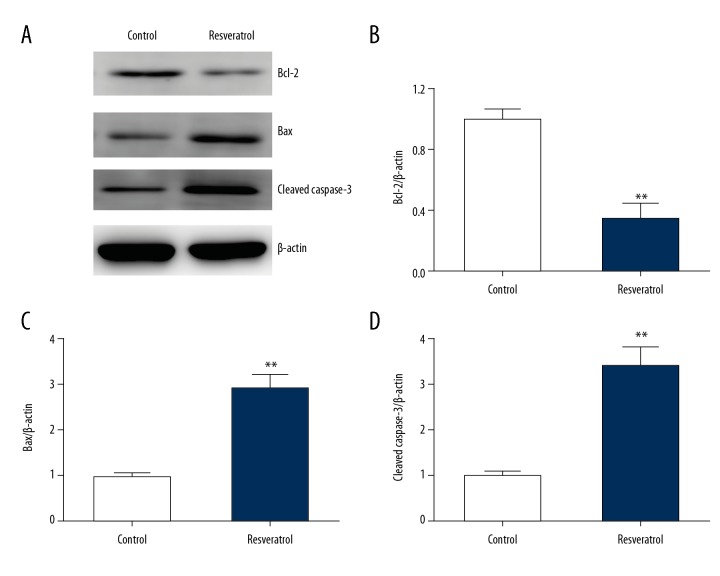

Resveratrol regulates expression of Bax and Bcl2 in TRAMP cells

WB was used to examine the effect of RES on expression of Bcl2 and Bax. RES supplementation remarkably downregulated Bcl2 expression and upregulated Bax expression in TRAMP cells (Figure 4A–4C). Moreover, RES supplementation upregulated the expression of cleaved caspase-3 in TRAMP cells (Figure 4D). This indicates that resveratrol enhanced the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins.

Figure 4.

Resveratrol regulates expression of Bax, Bcl2, and caspase-3 in TRAMP cells. TRAMP cells received a supplement of resveratrol (50 μM) for 24 h. (A–D) Representative immunoblots (A) as well as quantification of Bcl2 (B), Bax (C), and cleaved caspase-3 (D) with regard to TRAMP cells. Results are presented in the form of mean ±SEM from 3 independent experiments. ** P < 0.01 vs. control group.

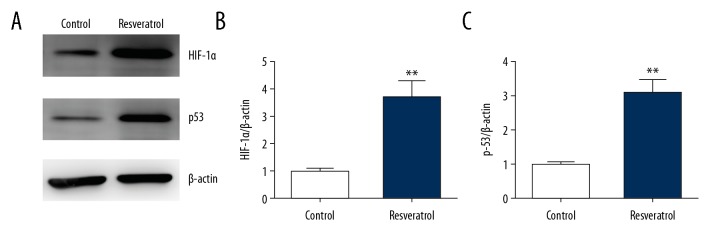

Resveratrol promotes expression of HIF-1α and p53 in TRAMP cells

WB was used to assess of the effect of RES on expression of p53 and HIF-1α in PCCs of mice, that is, TRAMP cells. RES remarkably upregulated HIF-1α expression in TRAMP cells (Figure 5A, 5B). In addition, p53 expression was also elevated in the RES-treated group (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Resveratrol promotes expression of p53 and HIF-1α in TRAMP cells. TRAMP cells received a supplement of resveratrol (50 μM) for 24 h. (A–C) Representative immunoblots (A) as well as quantification of HIF-1α (B) and p53 (C) in TRAMP cells. Results are presented in the form of mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. ** P<0.01 vs. control group.

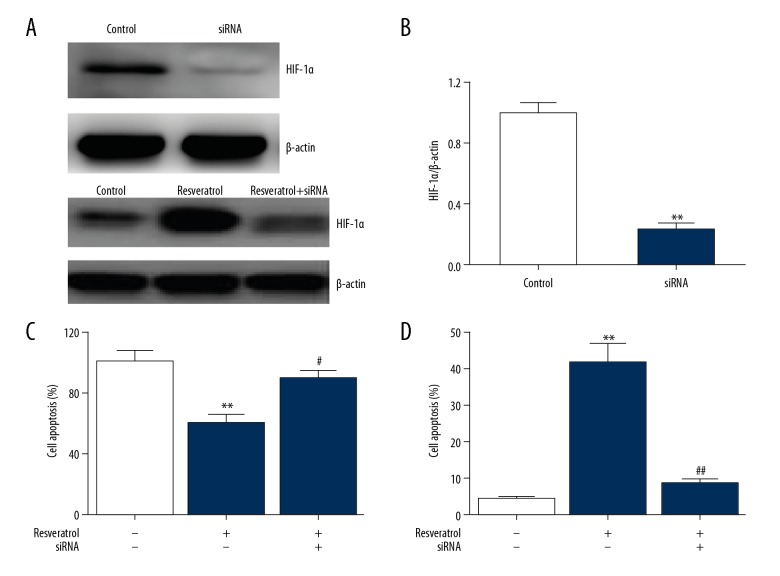

Resveratrol kills malignant cells via HIF-1α

To assess the influence of HIF-1 on cell apoptosis regulated by RES, we used siRNA specific to HIF-1α, showing that HIF-1 expression was downregulated in TRAMP cells (Figure 6A). RES suppressed cell survival and promoted cell death, but its effects were reversed after HIF-1α knockdown, as shown in Figure 6B, 6C. This suggests that the effects of RES in PC are mediated via HIF-1α.

Figure 6.

Resveratrol kills cancer cells via HIF-1α. TRAMP cells underwent 24-h transfection with HIF-1α siRNA and were subsequently supplemented with resveratrol (50 μM) for 24 h. (A, B) Representative immunoblots (A) as well as quantification of HIF-1α (B) in TRAMP cells. Results are presented in the form of mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. ** P<0.01 vs. control group. (C) CCK-8 assay was used to evaluate cell survival. (D) FC was used to evaluate cell death. Results are presented in the form of mean ±SEM from 3 independent experiments. ** P<0.01 vs. control group; # P<0.05, ## P<0.01 vs. resveratrol group.

Discussion

There is an urgent need to develop innovative strategies to prevent and treat PC [16]. Previous in vitro studies have revealed that resveratrol influences various agents associated with development of malignant cells [17–19]. With respect to PC, previous in vitro studies have revealed the influence of resveratrol on cell development, cell death, and cell cycle arrest [12,13]. Resveratrol promotes sensitivity to radiation and can downregulate androgen receptor (AR). Several in vivo studies in mice have suggested that resveratrol inhibits generation and proliferation of spontaneous PCs and xenograft malignancies [20]. In our study, we discovered that resveratrol suppressed cell survival and enhanced cell death in TRAMP cells characterized by elevated ROS level. Enhanced mitochondrial ROS levels cause malfunction in endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria, which triggers cell death. Moreover, Bcl2 participates in regulation of cell death mediated via the mitochondria-dependent pathway. Bax and Bcl2 are upstream regulators of mitochondria [21]. The ratio of Bax to Bcl2 plays an important part in triggering cell death. Consequently, in our study, resveratrol inhibited Bcl2 expression and enhanced Bax expression. Reinforced Bax expression triggers cell death. Furthermore, as a protein responsive to DNA damage as well as being a protector of cells, p53 also participates in triggering cell death [22]. Consequently, p53 expression was evaluated in TRAMP cells that received a supplement of resveratrol. Expression of p53 was elevated in TRAMP cells in comparison with the control group, suggesting that cell death triggered by resveratrol in TRAMP cells is related to enhanced p53 expression.

HIF-1α is induced under hypoxic conditions in various cancers. HIF-1α stimulates generation of vessels necessary for generation of malignancy, leading to aggression and progression [23]. HIF-1α plays an important role in physiological reaction to lack of oxygen, but its effect on malignancies is ambiguous [24]. Enhanced HIF-1α expression in several tumor cells, such as breast and kidney tumors, has been reported to enhance generation of vessels and viability of malignancies. However, in other tumors, such as ovarian carcinoma, enhanced HIF-1α expression promotes cell death [25]. With respect to PC, enhanced HIF-1α expression is associated with a shorter time before a biochemical recurrence in patients undergoing surgery or radiotherapy [26,27]. HIF-1α is upregulated independent of limited oxygen via various factors such as growth factors, free radicals, and oncogenes [28, 29]. In the present study, HIF-1α expression was always elevated in the resveratrol group compared to the control group of PCCs. Furthermore, HIF-1α knockdown eliminated the effects of resveratrol on cell death. Resveratrol promoted expression of HIF-1α, elevating ROS concentration, which induced expression of p53 and Bax, and suppressed Bcl2 expression. This was followed by enhanced caspase-3 expression, finally leading to cell death. The above findings suggest that HIF-1α is an important suppressor of the effects of resveratrol.

Conclusions

The most remarkable finding of this study is that the HIF-1α/ROS/p53 axis regulates the action of RES in TRAMP cells. RES upregulates HIF-1α expression, which enhances ROS concentration, and promotes expression of Bax and p53 while downregulating the expression of Bcl2. RES restores caspase-3 induction and promotes cell death. In summary, our study proves that resveratrol triggers cell death via the HIF-1α/ROS/p53 axis in PCCs. Our findings could provide innovative strategies to treat PC.

Footnotes

Source of support: Departmental sources

Conflict of interests

None.

References

- 1.Romero D. Prostate cancer: Genomic information improves risk prediction. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;15:68. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu J, Liao R, Su C, et al. Toxicity profile characteristics of novel androgen-deprivation therapy agents in patients with prostate cancer: A meta-analysis. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:193–98. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1419871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson D, Garmo H, Lissbrant IF, et al. Prostate cancer death after radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy: A nationwide population-based observational study. Eur Urol. 2018;73(4):502–11. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenner A. Prostate cancer: Resveratrol inhibits the AR. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:642. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A, Rimando AM, Levenson AS. Resveratrol and pterostilbene as a microRNA-mediated chemopreventive and therapeutic strategy in prostate cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2017;1403(1):15–26. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YA, Lien HM, Kao MC, et al. Sensitization of radioresistant prostate cancer cells by resveratrol isolated from Arachis hypogaea stems. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou P, Liu X, Li G, Wang Y. Resveratrol pretreatment attenuates traumatic brain injury in rats by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation via SIRT1. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:3212–17. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buttari B, Profumo E, Segoni L, et al. Resveratrol counteracts inflammation in human M1 and M2 Macrophages upon challenge with 7-oxo-cholesterol: Potential therapeutic implications in atherosclerosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/257543. 257543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Cao X, Cui Y, et al. Resveratrol alleviates lysophosphatidylcholine-induced damage and inflammation in vascular endothelial cells. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(3):4011–18. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nana AW, Chin YT, Lin CY, et al. Tetrac downregulates β-catenin and HMGA2 to promote the effect of resveratrol in colon cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2018;25:279–93. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson A, Alderete KS, Mko G, et al. Anticancer effects of resveratrol in canine hemangiosarcoma cell lines. Vet Comp Oncol. 2018;16(2):253–61. doi: 10.1111/vco.12375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Empl MT, Albers M, Wang S, Steinberg P. The resveratrol tetramer r – viniferin induces a cell cycle arrest followed by apoptosis in the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. Phytother Res. 2015;29:1640–45. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitani T, Harada N, Tanimori S, et al. Resveratrol inhibits hypoxia-inducible factor-1α-mediated androgen receptor signaling and represses tumor progression in castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2014;60(4):276–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Csiszar A, Smith K, Labinskyy N. Resveratrol attenuates TNF-alpha-induced activation of coronary arterial endothelial cells: Role of NF-kappaB inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(4):H1694–99. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00340.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moon SO, Kim W, Sung MJ, et al. Resveratrol suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced fractalkine expression in endothelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:112–19. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saunier E, Antonio S, Regazzetti A, et al. Resveratrol reverses the Warburg effect by targeting the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in colon cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6945. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07006-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanquerrosselló MD, Hernándezlópez R, Roca P, et al. Resveratrol induces mitochondrial respiration and apoptosis in SW620 colon cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2017;1861(2):431–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan BC, Mock CD, Thilagavathi R, Selvam C. Molecular mechanisms of curcumin and its semisynthetic analogues in prostate cancer prevention and treatment. Life Sci. 2016;152:135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko JH, Sethi G, Um JY, et al. The role of resveratrol in cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2589. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Wen X, Li M, et al. Targeting cancer stem cells and signaling pathways by resveratrol and pterostilbene. Biofactors. 2018;44(1):61–68. doi: 10.1002/biof.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yousef M, Vlachogiannis IA, Tsiani E. Effects of resveratrol against lung cancer: In vitro and in vivo studies. Nutrients. 2017;9 doi: 10.3390/nu9111231. pii: E1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundqvist J, Tringali C, Oskarsson A. Resveratrol, piceatannol and analogs inhibit activation of both wild-type and T877A mutant androgen receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;174:161–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan L, Tan B, Li Y, et al. Upregulation of miR-185 promotes apoptosis of the human gastric cancer cell line MGC803. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:3115–22. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.8206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiseljak-Vassiliades K, Mills TS, Zhang Y, et al. Elucidating the Role of the desmosome protein p53 apoptosis effector related to PMP-22 (PERP) in growth hormone tumors. Endocrinology. 2017;158:1450–60. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ranasinghe WK, Baldwin GS, Bolton D, et al. HIF1α expression under normoxia in prostate cancer – which pathways to target? J Urol. 2015;193:763–70. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tianchi YU, Tang B. Development of inhibitors targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and hypoxia-inducible factor-2 for cancer therapy. Medical Recapitulate. 2017 doi: 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.3.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masoud GN, Li W. HIF-1α pathway: Role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2015;5:378–89. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu J, Yang L, Zeng J, et al. Knockdown of HIF-1α by siRNA-expressing plasmid delivered by attenuated Salmonella enhances the antitumor effects of cisplatin on prostate cancer. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:7546. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07973-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li XD, Zi H, Fang C, Zeng XT. Association betweenHIF1Ars11549465 polymorphism and risk of prostate cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:44910–16. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]