Abstract

Objective

To determine if using a parachute prevents death or major traumatic injury when jumping from an aircraft.

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Private or commercial aircraft between September 2017 and August 2018.

Participants

92 aircraft passengers aged 18 and over were screened for participation. 23 agreed to be enrolled and were randomized.

Intervention

Jumping from an aircraft (airplane or helicopter) with a parachute versus an empty backpack (unblinded).

Main outcome measures

Composite of death or major traumatic injury (defined by an Injury Severity Score over 15) upon impact with the ground measured immediately after landing.

Results

Parachute use did not significantly reduce death or major injury (0% for parachute v 0% for control; P>0.9). This finding was consistent across multiple subgroups. Compared with individuals screened but not enrolled, participants included in the study were on aircraft at significantly lower altitude (mean of 0.6 m for participants v mean of 9146 m for non-participants; P<0.001) and lower velocity (mean of 0 km/h v mean of 800 km/h; P<0.001).

Conclusions

Parachute use did not reduce death or major traumatic injury when jumping from aircraft in the first randomized evaluation of this intervention. However, the trial was only able to enroll participants on small stationary aircraft on the ground, suggesting cautious extrapolation to high altitude jumps. When beliefs regarding the effectiveness of an intervention exist in the community, randomized trials might selectively enroll individuals with a lower perceived likelihood of benefit, thus diminishing the applicability of the results to clinical practice.

Introduction

Parachutes are routinely used to prevent death or major traumatic injury among individuals jumping from aircraft. However, evidence supporting the efficacy of parachutes is weak and guideline recommendations for their use are principally based on biological plausibility and expert opinion.1 2 Despite this widely held yet unsubstantiated belief of efficacy, many studies of parachutes have suggested injuries related to their use in both military and recreational settings,3 4 and parachutist injuries are formally recognized in the World Health Organization’s ICD-10 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision).5 This could raise concerns for supporters of evidence-based medicine, because numerous medical interventions believed to be useful have ultimately failed to show efficacy when subjected to properly executed randomized clinical trials.6 7

Previous attempts to evaluate parachute use in a randomized setting have not been undertaken owing to both ethical and practical concerns. Lack of equipoise could inhibit recruitment of participants in such a trial. However, whether pre-existing beliefs about the efficacy of parachutes would, in fact, impair the enrolment of participants in a clinical trial has not been formally evaluated. To address these important gaps in evidence, we conducted the first randomized clinical trial of the efficacy of parachutes in reducing death and major injury when jumping from an aircraft.

Methods

Study protocol

Between September 2017 and August 2018, individuals were screened for inclusion in the PArticipation in RAndomized trials Compromised by widely Held beliefs aboUt lack of Treatment Equipoise (PARACHUTE) trial. Prospective participants were approached and screened by study investigators on commercial or private aircraft.

For the commercial aircraft, travel was related to trips the investigators were scheduled to take for business or personal reasons unrelated to the present study. Typically, passengers seated close to the study investigator (typically not known acquaintances) would be approached mid-flight, between the time of initial seating and time of exiting the aircraft. The purpose and design of the study were explained. Owing to difficulty in enrolling patients at several thousand meters above the ground, we expanded our approach to include screening members of the investigative team, friends, and family. For the private aircraft, the boarding of aircraft was done for the explicit purpose of participating in the trial.

All participants were asked whether they would be willing to be randomized to jump from the aircraft at its current altitude and velocity. Potential study participants completed an anonymous survey using a survey app on the screening investigator’s phone or tablet. Responses were transmitted to an online database upon landing for later analysis.

We enrolled individuals willing to participate in the trial and meeting inclusion criteria in the study. We randomized patients (1:1) to the intervention or the control. We obtained written informed consent. Participants were then instructed to jump from the aircraft after being provided their assigned device. Jumps were conducted at two sites in the US: Katama Airfield in Martha’s Vineyard, MA (conducted by investigators from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center), and the Yankee Air Museum in Belleville, MI (conducted by investigators from the University of Michigan). The same protocol was followed at each site, but the type of aircraft (airplane v helicopter) differed between the two sites.

Study population

Participants aged 18 and over, seated on an aircraft, and deemed to be rational decision makers by the enrolling investigator were eligible. Only participants who were willing to be randomized in the study were ultimately enrolled and randomized. Most of the participants who were randomized were study investigators.

Interventions

Participants were randomized to wear either a parachute (National 360, National Parachute Industries, Inc, Palenville, NY; or Javelin Odyssey, Sun Path Products, Inc, Raeford, NC; supplementary materials fig 1) or an empty backpack (The North Face, Inc, Alameda, CA; or Javelin Odyssey Gearbag, Sun Path Products, Inc). The interventions were not blinded to either participants or study investigators.

Randomization

We used block randomization, stratified by site and sex with a block size of two. The trial statistician created the randomization sequence by using the R package blockrand. The research team had previously assigned unique numeric identifiers to each participant. At both sites, only one team member had access to the list of numeric identifiers. Participants were verbally assigned their treatment, which was done by order of enrolment. Allocation was not concealed to the investigator who assigned the treatment.

Data collection

We collected data on basic demographic characteristics during screening by using paper forms or the survey app.8 Characteristics included age, sex, ethnic group, height, and weight. We also collected information on participants’ medical history including a history of broken bones, acrophobia (fear of heights), previous parachute use, family history of parachute use, and frequent flier status. Flight characteristics included carrier, velocity, altitude, make and model of the aircraft, the individual’s seating section, and whether the flight was international or domestic. Velocity and altitude were captured by using flight information provided by aircraft on individual television screens when available, as well as through pilot announcements. When neither was directly available, visual estimations were made by the study investigators.

At the time of each jump, researchers recorded the altitude and velocity of the aircraft, and conducted a follow-up interview with each participant to ascertain vital status and to record any injuries sustained from the free fall within five minutes of impact with the ground, and again at 30 days after impact. We collected data electronically or with paper forms and uploaded the data to an online deidentified, password protected database.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the composite of death and major traumatic injury, defined by an Injury Severity Score greater than 15, within five minutes of impact. The Injury Severity Score is a commonly used anatomical scoring system to grade the severity of traumatic injuries.9 Separate scores are assigned to each of six anatomical regions, and the three most highly injured regions contribute to a final score ranging from 0 to 75. Higher scores indicate a more severe injury. Secondary outcomes included death and major traumatic injury assessed at 30 days after impact using the Injury Severity Score, as well as 30 day quality of life assessed by the Short Form Health Survey. The Short Form Health Survey is a multipurpose questionnaire that measures a patient’s overall health-related quality of life based on mental and physical functioning.10

Statistical analysis

The primary efficacy analysis tested the hypothesis that parachute use is superior to the control in preventing death and major traumatic injury. Based on an assumption of an average jump altitude of 4000 meters (typical of skydiving) and the anticipated effect of impact with the Earth at terminal velocity on human tissue, we projected that 99% of the control arm would experience the primary outcome at ground impact with a relative risk reduction of 95% in the intervention arm. A sample size of 14 (7 in each arm) would yield 99% power to detect this difference at a two sided α of 0.05. In anticipation of potential withdrawal after enrolment owing to last minute anxieties, a total sample size of 20 participants was targeted. Analysis was performed on an intention-to-treat basis. We performed secondary subgroup analyses stratified by aircraft type (airplane v helicopter) and previous parachute use through formal tests of statistical interaction.

We summarized continuous variables by mean (standard deviation) and categorical variables by frequency and percentage. We tabulated baseline characteristics of the two trial arms to examine for potential imbalance in variables. We tested for differences between the outcomes of the two trial arms by using Student’s t test (continuous variables) and Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables). To better understand what drove the willingness to participate in the trial, we also compared characteristics of individuals who were screened but chose not to enroll with individuals who enrolled. Baseline characteristics between those enrolled and not enrolled were compared using the same statistical tests. Confidence intervals for the difference in continuous outcomes between the two arms were constructed using T distributions. We could not calculate confidence intervals for the difference between arms (eg, risk difference, odds ratio, or relative risk) because no events were observed for any of the binary outcomes in either arm.

We performed all analyses by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

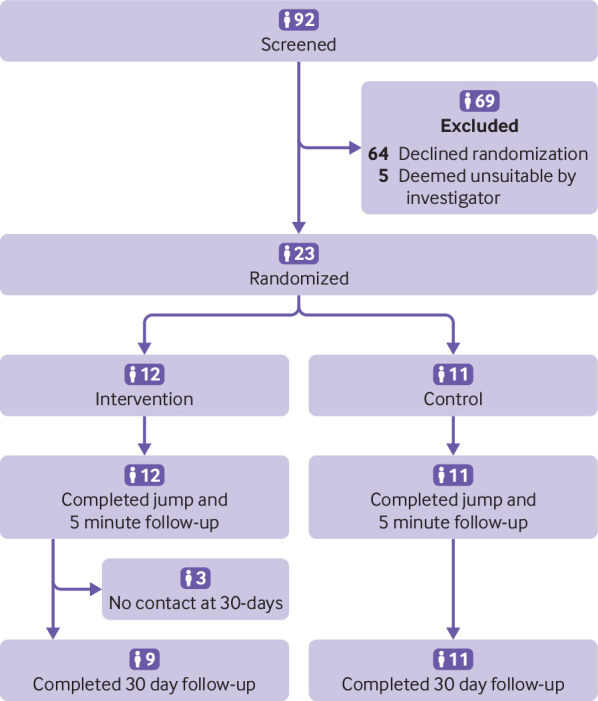

A total of 92 individuals were screened and surveyed regarding their interest in participating in the PARACHUTE trial. Among those screened, 69 (75%) were unwilling to be randomized or found to be otherwise ineligible by investigators. Figure 1 shows that a total of 23 individuals were deemed eligible for randomization.

Fig 1.

Study flow diagram

Table 1 shows that the baseline characteristics of enrolled participants were generally similar between the intervention and control arms. The median age of randomized participants was 38 years and 13 (57%) were male. Three (13%) of the randomized participants had previous parachute use and nine (39%) had a history of acrophobia. Table 2 shows that participants in the study were similar to those screened but not enrolled with regard to most demographic and clinical characteristics. However, participants were less likely to be on a jetliner, and instead were on a biplane or helicopter (0% v 100%; P<0.001), were at a lower mean altitude (0.6 m, SD 0.1 v 9146 m, SD 2164; P<0.001), and were traveling at a slower velocity (0 km/h, SD 0 v 800 km/h, SD 124; P<0.001) (table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants randomized to parachute versus control. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Parachute | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 11 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Demographics | ||

| Median (SD) age (years) | 38.1 (8.7) | 38.6 (11.0) |

| Women | 4 (36) | 6 (50) |

| Men | 7 (64) | 6 (50) |

| Ethnic group: | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| East Asian or South Asian | 4 (36) | 4 (33) |

| Black or African American | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| More than one race | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| White | 7 (64) | 8 (67) |

| Mean (SD) height (cm) | 171.8 (9.1) | 171.7 (8.4) |

| Mean (SD) weight (kg) | 75.9 (24.4) | 74.6 (13.0) |

| Medical history | ||

| Broken bones | 4 (36) | 5 (42) |

| Acrophobia | 3 (27) | 6 (50) |

| Parachute use | 3 (27) | 0 (0) |

| Family history of parachute use | 2 (18) | 0 (0) |

| Frequent flier (average >4 flights per month) | 0 (0) | 4 (33) |

| Flight | ||

| International v domestic: | ||

| International | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Domestic | 11 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Aircraft type: | ||

| Jetliner | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Biplane | 5 (46) | 6 (50) |

| Helicopter | 6 (55) | 6 (50) |

| Mean (SD) velocity (km/h) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mean (SD) altitude (m) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) |

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants versus screened individuals. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Participants | Screened | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 23 | 69 | |

| Demographics | |||

| Median (SD) age (years) | 38.4 (9.7) | 43.0 (14.9) | 0.1 |

| Women | 10 (44) | 32 (46) | |

| Men | 13 (57) | 37 (54) | |

| Ethnic group: | 0.4 | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| East Asian or South Asian | 8 (35) | 13 (19) | |

| Black or African American | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| More than one race | 0 (0) | 4 (6) | |

| White | 15 (65) | 48 (70) | |

| Mean (SD) height (cm) | 171.7 (8.5) | 171.2 (11.0) | 0.8 |

| Mean (SD) weight (kg) | 75.2 (18.9) | 73.5 (15.5) | 0.7 |

| Medical history | |||

| Broken bones | 9 (39) | 26 (38) | 0.9 |

| Acrophobia | 9 (39) | 23 (33) | 0.6 |

| Parachute use | 3 (13) | 9 (13) | >0.9 |

| Family history of parachute use | 2 (8.7) | 10 (15) | 0.7 |

| Frequent flier (average >4 flights per month) | 4 (17) | 14 (20) | >0.9 |

| Flight | |||

| International v domestic flight: | 0.02 | ||

| International | 0 (0) | 8 (21) | |

| Domestic | 23 (100) | 31 (80) | |

| Aircraft type: | <0.001 | ||

| Jetliner | 0 (0) | 69 (100) | |

| Biplane | 11 (48) | 0 (0) | |

| Helicopter | 12 (52) | 0 (0) | |

| Mean (SD) velocity (km/h) | 0 (0) | 800 (124) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SD) altitude (m) | 0.6 (0.1) | 9146 (2164) | <0.001 |

Among the 12 participants randomized to the intervention arm, the parachute did not deploy in all 12 (100%) owing to the short duration and altitude of falls. Among the 11 participants randomized to receive an empty backpack, none crossed over to the intervention arm. Figure 2 shows a representative jump (additional jumps are shown in supplementary materials fig 2).

Fig 2.

Representative study participant jumping from aircraft with an empty backpack. This individual did not incur death or major injury upon impact with the ground

Outcomes

Table 3 shows the results for the primary and secondary outcomes. There was no significant difference in the rate of death or major traumatic injury between the treatment and control arms within five minutes of ground impact (0% for parachute v 0% for control; P>0.9) or at 30 days after impact (0% for parachute v 0% for control; P>0.9). Health status as measured by the Short Form Health Survey was similar between groups (43.9, SD 1.8 for parachute v 44.0, SD 2.4 for control; P=0.9; mean difference of 0.1, 95% confidence interval −2.0 to 2.2). In subgroup analyses, there were no significant differences in the effect of parachute use on outcomes when stratified by type of aircraft or previous parachute use (P>0.9 for interaction for both comparisons).

Table 3.

Event rates for primary and secondary endpoints. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Endpoint | Parachute | Control | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On impact | ||||

| Death or major traumatic injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | >0.9 |

| Mean (SD) Injury Severity Score | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | >0.9 |

| 30 days after impact | ||||

| Death or major traumatic injury | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | >0.9 |

| Mean (SD) Injury Severity Score | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 | >0.9 |

| Health status | ||||

| Mean (SD) Short Form Health Survey score | 43.9 (1.8) | 44.0 (2.4) | 0.1 (−2.0 to 2.2) | 0.9 |

| Mean (SD) physical health subscore | 19.6 (0.7) | 19.7 (0.5) | 0.04 (−0.5 to 0.6) | 0.9 |

| Mean (SD) mental health subscore | 24.3 (1.3) | 24.3 (2.1) | 0.08 (−1.6 to 1.8) | 0.9 |

Discussion

We have performed the first randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of parachutes for preventing death or major traumatic injury among individuals jumping from aircraft. Our groundbreaking study found no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome between the treatment and control arms. Our findings should give momentary pause to experts who advocate for routine use of parachutes for jumps from aircraft in recreational or military settings.

Although decades of anecdotal experience have suggested that parachute use during jumps from aircraft can save lives, these observations are vulnerable to selection bias and confounding. Indeed, in seminal work published in the BMJ in 2003, a systematic search by Smith and Pell for randomized clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of parachutes during gravitational challenge yielded no published studies.1 In part, our study was designed as a response to their call to (broken) arms in order to address this critical knowledge gap.

Beliefs about the efficacy of commonly used, but untested, interventions often influence daily clinical decision making. These beliefs can expose patients to unnecessary risk without clear benefit and increase healthcare costs.11 Beliefs grounded in biological plausibility and expert opinion have been proven wrong by subsequent rigorous randomized evaluations.12 The PARACHUTE trial represents one more such historic moment.

Should our results be reproduced in future studies, the end of routine parachute use during jumps from aircraft could save the global economy billions of dollars spent annually to prevent injuries related to gravitational challenge.

A minor caveat to our findings is that the rate of the primary outcome was substantially lower in this study than was anticipated at the time of its conception and design, which potentially underpowered our ability to detect clinically meaningful differences, as well as important interactions. Although randomized participants had similar characteristics compared with those who were screened but did not enroll, they could have been at lower risk of death or major trauma because they jumped from an average altitude of 0.6 m (SD 0.1) on aircraft moving at an average of 0 km/h (SD 0). Clinicians will need to consider this information when extrapolating to their own settings of parachute use.

Opponents of evidence-based medicine have frequently argued that no one would perform a randomized trial of parachute use. We have shown this argument to be flawed, having conclusively shown that it is possible to randomize participants to jumping from an aircraft with versus without parachutes (albeit under limited and specific scenarios). In our study, we had to screen many more individuals to identify eligible and willing participants. This is not dissimilar to the experiences of other contemporary trials that frequently enroll only a small fraction of the thousands of patients screened. Previous research has suggested that participants in randomized clinical trials are at lower risk than patients who are treated in routine practice.13 14 This is particularly relevant to trials examining interventions that the medical community believes to be effective: lack of equipoise often pushes well meaning but ill-informed doctors or study investigators to withhold patients from study participation, as they might believe it to be unethical to potentially deny their patients a treatment they (wrongly) believe is effective.

Critics of the PARACHUTE trial are likely to make the argument that even the most efficacious of treatments can be shown to have no effect in a randomized trial if individuals who would derive the greatest benefit selectively decline participation. The critics will claim that although few medical treatments are likely to be as effective as parachutes,15 the exclusion of selected patients could result in null trial results, whether or not the intervention being evaluated was truly effective. The critics might further argue that although randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for evaluating treatments, their results are not always guaranteed to be relevant for clinicians. It will be up to the reader to determine the relevance of these findings in the real world.

Strengths and weaknesses of this study

A key strength of the PARACHUTE trial was that it was designed and initially powered to detect differences in the combination of death and major traumatic injury. Although the use of softer endpoints, such as levels of fear before and after jumping, or its surrogates, such as loss of urinary continence, could have yielded more power to detect an effect of parachutes, we believe that that our selection of bias-resistant endpoints that are meaningful to all patients increases the clinical relevance of the trial.

The study also has several limitations. First and most importantly, our findings might not be generalizable to the use of parachutes in aircraft traveling at a higher altitude or velocity. Consideration could be made to conduct additional randomized clinical trials in these higher risk settings. However, previous theoretical work supporting the use of parachutes could reduce the feasibility of enrolling participants in such studies.16

Second, our study was not blinded to treatment assignment. We did not anticipate a strong placebo effect for our primary endpoint, but it is possible that other subjective endpoints would have necessitated the use of a blinded sham parachute as a control.

Third, the individuals screened but not enrolled in the study were limited to passengers unfortunate enough to be seated near study investigators during commercial flights, and might not be representative of all aircraft passengers. The participants who did ultimately enroll, agreed with the knowledge that the aircraft were stationary and on the ground.

Finally, although all endpoints in the study were prespecified, we were unable to register the PARACHUTE trial prospectively. We attempted to register this study with the Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry (application number APPL/2018/040), a member of the World Health Organization’s Registry Network of the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. After several rounds of discussion, the Registry declined to register the trial because they thought that “the research question lacks scientific validity” and “the trial data cannot be meaningful.” We appreciated their thorough review (and actually agree with their decision).

The PARACHUTE trial satirically highlights some of the limitations of randomized controlled trials. Nevertheless, we believe that such trials remain the gold standard for the evaluation of most new treatments. The PARACHUTE trial does suggest, however, that their accurate interpretation requires more than a cursory reading of the abstract. Rather, interpretation requires a complete and critical appraisal of the study. In addition, our study highlights that studies evaluating devices that are already entrenched in clinical practice face the particularly difficult task of ensuring that patients with the greatest expected benefit from treatment are included during enrolment.

To safeguard this last issue, we see several solutions. First, overcoming such a hurdle requires extreme commitment on the part of the investigators, clinicians, and patients; thankfully, recent examples of such efforts do exist.17 Second, stronger efforts could be made to ensure that definitive trials are conducted before new treatments become inculcated into routine practice, when greater equipoise is likely to exist. Third, the comparison of baseline characteristics and outcomes of study participants and non-participants should be utilized more frequently and reported consistently to facilitate the interpretation of results and the assessment of study generalizability.14 Finally, there could be instances where clinical beliefs justifiably prevent a true randomized evaluation of a treatment from being conducted.

Conclusion

Parachute use compared with a backpack control did not reduce death or major traumatic injury when used by participants jumping from aircraft in this first randomized evaluation of the intervention. This largely resulted from our ability to only recruit participants jumping from stationary aircraft on the ground. When beliefs regarding the effectiveness of an intervention exist in the community, randomized trials evaluating their effectiveness could selectively enroll individuals with a lower likelihood of benefit, thereby diminishing the applicability of trial results to routine practice. Therefore, although we can confidently recommend that individuals jumping from small stationary aircraft on the ground do not require parachutes, individual judgment should be exercised when applying these findings at higher altitudes.

What is already known on this topic

Parachutes are routinely used to prevent death or major traumatic injury among individuals jumping from aircraft, but their efficacy is based primarily on biological plausibility and expert opinion

No randomized controlled trials of parachute use have yet been attempted, presumably owing to a lack of equipoise

What this study adds

This randomized trial of parachute use found no reduction in death or major injury compared with individuals jumping from aircraft with an empty backpack

Lack of enrolment of individuals at high risk could have influenced the results of the trial

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Creato, Alyssa DaSilva, Guillermo DaSilva, and Ethan Creato at Classic Aviators, Ltd, 12 Mattakesett Way, Katama Airfield in Martha’s Vineyard, MA, (www.biplanemv.com) for the use of their biplanes and the team at Yankee Air Museum in Belleville, MI for the use of their Bell UH-1 Iroquois (Huey) helicopter for our study.

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary materials: Supplementary materials and figures 1 and 2

Contributors: RWY had the original idea but was reluctant to say it out loud for years. In a moment of weakness, he shared it with MWY and BKN, both of whom immediately recognized this as the best idea RWY will ever have. RWY and LRV wrote the first draft. CS, DBK, JBS, EAS, and JLH provided critical review. RMD provided subject matter expertise. DSK took this work to another satirical level. All authors suffered substantial abdominal discomfort from laughter. RWY worried that BKN would not keep his mouth shut until the Christmas issue was published. All authors had full access to the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. RWY is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: There was no funding source for this study.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This research has the ethical approval of the Institutional Review Board of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (protocol no 2018P000441).

Data sharing: Anonymized trial data are available from the corresponding author.

The manuscript’s guarantor (RWY) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned have been explained.

References

- 1. Smith GC, Pell JP. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2003;327:1459-61. 10.1136/bmj.327.7429.1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Parachute Association. Skydiver's Information Manual, 2018. https://uspa.org/Portals/0/files/Man_SIM_2018.pdf

- 3. Knapik J, Steelman R. Risk factors for injuries during military static-line airborne operations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Athl Train 2016;51:962-80. 10.4085/1062-6050-51.9.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ellitsgaard N. Parachuting injuries: a study of 110,000 sports jumps. Br J Sports Med 1987;21:13-7. 10.1136/bjsm.21.1.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ICD-10-CM Code V97.2. Parachutist Accident. https://icd.codes/icd10cm/V972

- 6. Echt DS, Liebson PR, Mitchell LB, et al. Mortality and morbidity in patients receiving encainide, flecainide, or placebo. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. N Engl J Med 1991;324:781-8. 10.1056/NEJM199103213241201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:321-33. 10.1001/jama.288.3.321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.QuickTapSurvey [program]: TabbleDabble Inc., Toronto, Canada. https://www.quicktapsurvey.com

- 9. Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W, Jr, Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma 1974;14:187-96. 10.1097/00005373-197403000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220-33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schwartz AL, Landon BE, Elshaug AG, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Measuring low-value care in Medicare. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1067-76. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kunz R, Oxman AD. The unpredictability paradox: review of empirical comparisons of randomised and non--randomised clinical trials. BMJ 1998;317:1185-90. 10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nallamothu BK, Hayward RA, Bates ER. Beyond the randomized clinical trial: the role of effectiveness studies in evaluating cardiovascular therapies. Circulation 2008;118:1294-303. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kennedy-Martin T, Curtis S, Faries D, Robinson S, Johnston J. A literature review on the representativeness of randomized controlled trial samples and implications for the external validity of trial results. Trials 2015;16:495. 10.1186/s13063-015-1023-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hayes MJ, Kaestner V, Mailankody S, Prasad V. Most medical practices are not parachutes: a citation analysis of practices felt by biomedical authors to be analogous to parachutes. CMAJ Open 2018;6:E31-8. 10.9778/cmajo.20170088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Newton SI. Law of Universal Gravitation. Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, 1687. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi H-M, et al. ORBITA investigators Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA): a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018;391:31-40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32714-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials: Supplementary materials and figures 1 and 2