Abstract

Background:

Gun violence and psychological problems are often conflated in public discourse on gun safety. However, few studies have empirically assessed the effect of exposure to violence when exploring the association between gun carrying and psychological distress.

Objective:

To examine the potential effect of exposure to violence on the associations between gun carrying and psychological distress among vulnerable adolescents.

Design:

Longitudinal cohort study.

Setting:

The Pathways to Desistance study, a study of youths found guilty of a serious criminal offense in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, or Maricopa County, Arizona.

Participants:

1170 male youths aged 14 to 19 years who had been found guilty of a serious criminal offense.

Measurements:

Youths were assessed at baseline and at four 6-month intervals with regard to gun carrying (“Have you carried a gun?”), psychological distress (Global Severity Index), and exposure to violence (modified version of the Exposure to Violence Inventory).

Results:

At the bivariate level, gun carrying was consistently associated with higher levels of psychological distress. However, the association between psychological distress and gun carrying diminished or disappeared when exposure to violence was considered. Exposure to violence (as either a victim or a witness) was significantly related to gun carrying at all follow-up assessments, with increased odds of gun carrying ranging from 1.43 to 1.87 with each additional report of exposure to violence.

Limitations:

The study sample was limited to justice-involved male youths. Precarrying distress and exposure to violence could not be fully captured because many participants had initiated gun carrying before baseline.

Conclusion:

In male youths involved in the criminal justice system, the relationship between psychological distress and gun carrying seems to be influenced by exposure to violence (either experiencing or witnessing it). Further study is warranted to explore whether interventions after exposure to violence could reduce gun carrying in this population.

Primary Funding Source:

None.

Gun carrying among youths is a significant public health concern in the United States (1). Those who carry weapons are at increased risk for fighting, being injured and hospitalized, or injuring others (2–4). Firearm-associated homicide and suicide are leading causes of death among American youths (aged 10 to 24 years); rates observed among African American and Hispanic youths are disproportionately high (5).

Weapon carrying and exposure to violence have been repeatedly linked in research using samples of minority, inner-city youths (6, 7). Weapon carrying is viewed primarily as a protection-driven behavior resulting from a combination of 3 factors: fear of crime, risk perception of crime victimization, and prior victimization (8, 9). Some suggest that gun violence and psychological distress may be related, with psychological distress increasing gun carrying (10, 11). However, prior empirical examinations of this relationship among adults (12) and youths (12, 13) are limited and have relied on cross-sectional designs (12). Even less is known about the effect of exposure to violence on the association between psychological distress and gun carrying.

What is understood is that victims of crime, especially violent crime, can experience enduring deterioration in their emotional health, with symptoms of anxiety, depression, hostility, and fear (14, 15). For example, youths who are repeatedly bullied may become aggressive and hypersensitive to threats and may mis-interpret even minor slights as deliberate cruelty (16, 17). The schema of an aggressive-reactive victim has been supported by findings that link victims of bullying to violent and antisocial behaviors, including frequent fighting, carrying a weapon, and perpetrating school-related homicides (18–20). Certain psychological symptoms—specifically paranoia, delusions, and depression—have been retrospectively linked to 60% of mass shootings in the United States (21, 22).

In light of the continuing prevalence of gun violence among vulnerable adolescents and the pressing need for greater understanding of the mechanisms driving gun carrying, our study examined 3 research hypotheses clarifying the associations among gun carrying, psychological distress, and exposure to violence. First, we expected gun carrying to be linked to higher levels of psychological distress (21). Second, we expected that exposure to violence (both experienced and witnessed) would predict gun carrying (14, 15). Finally, we hypothesized that the association between psychological distress and gun carrying would become less prominent when we considered the effect of exposure to violence, as either a victim or a witness (23, 24). Understanding mechanisms, such as psychological distress and exposure to violence, that drive gun carrying among adolescents has important implications for effective delivery of services aimed at averting risk and maximizing protection from gun violence for vulnerable adolescents, their families, and their communities.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection Procedures

Data used in this study were collected as part of the Pathways to Desistance study, a longitudinal investigation of the transition of justice-involved adolescents into adulthood (25, 26). Adolescents participating in the Pathways to Desistance study had been found guilty of a serious offense (almost exclusively felony-level violent crime, property offense, or drug offense) in juvenile or adult court in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania (Philadelphia), or Maricopa County, Arizona (Phoenix), between November 2000 and January 2003. To avoid overrepresentation of drug offenders in the study, the proportion of males found guilty of a drug charge who were invited to participate was capped at 15%. The participation rate (the percentage of those invited to participate who enrolled) was 67%, and the refusal rate (the percentage of those invited to participate who did not) was 20%. These figures are favorable compared with other studies in high-risk populations (27).

Data collected from male youths (n = 1170) at the baseline assessment and 4 follow-up assessments conducted at 6-month intervals were used to study the temporal associations among gun carrying, psychological distress, and exposure to violence during adolescence. The retention rates of study participants were 94% at the 6-month follow-up, 93% at the 12-month follow-up, and 91% at the 18- and 24-month follow-ups. Further information on institutional review board approvals, recruitment, descriptions of the total sample, and data collection procedures are available in other published work (27) and at the study Web site (www.pathwaysstudy.pitt.edu).

Measures

Gun carrying was based on responses to the question, “Have you carried a gun?” gathered at the baseline and follow-up assessments. This item was taken from the Self-Reported Offending survey (28). At each assessment, participants reported gun carrying within the previous 6 months.

Scores on the Global Severity Index (GSI), computed from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) scales, were used to measure general psychological distress at the baseline and follow-up assessments. The BSI is a 53-item self-reported inventory in which participants rate the extent to which they have been bothered (0 [not at all] to 4 [extremely]) in the past week by various symptoms (29). Nine BSI subscales are designed to assess various symptom groups, including somatization (for example, “Faintness or dizziness”), obsessive-compulsive (for example, “Having to check and double-check what you do”), interpersonal sensitivity (for example, “Feeling inferior to others”), depression (for example, “Feelings of worthlessness”), anxiety (for example, “Feeling tense or keyed up”), hostility (for example, “Having urges to beat, injure or harm someone”), phobic anxiety (for example, “Feeling uneasy in crowds, such as shopping or at a movie”), paranoid ideation (for example, “Feeling that most people cannot be trusted”), and psychoticism (for example, “Never feeling close to another person”). The reliability and validity of the BSI have been examined in many studies, and the inventory is generally considered an adequate measure of psychological symptoms and distress (30). The GSI score was computed by using the mean of scores across the 9 subscales and had good internal consistency, with the Cronbach α ranging from 0.95 to0.96 across all stages of data collection.

Exposure to violence was based on responses gathered at the baseline and follow-up assessments using a modified version of the Exposure to Violence Inventory (31). The exposure-to-violence measure con tained 2 subscales. One subscale included 6 items documenting experienced violence (for example, “Have you ever been shot?”), and the second contained 7 items documenting witnessed or observed violence (for example, “Have you ever seen someone else being shot?”). The exposure-to-violence measures collected information on witnessed and experienced violence during the participants’ lifetime at the baseline assessment and during the recall period (the previous 6 months) at the follow-up assessments. To assess the internal consistency of the exposure-to-violence items, confirmatory factor analyses were conducted for each of the subscales. Based on the model fit indices for the confirmatory factor analyses, the factor structures of the subscales for experiencing and witnessing violence were found to be acceptable.

Study site, age, and race/ethnicity (white, African American, Hispanic, or other), all of which potentially influence gun carrying, were included as control variables in the multivariate models. To control for the effect of youths being out of the community in a controlled environment on the associations among carrying, GSI score, and exposure to violence, the proportion of time participants spent on the streets was included in each of the multivariate analyses.

Statistical Analysis

First, descriptive and bivariate analyses were conducted to provide an understanding of the study sample and the associations among gun carrying, GSI score, and exposure to violence. Concurrent bivariate associations among these 3 variables were examined at each time point. For each period, participants were grouped by whether they reported carrying a gun during that period (active carrying vs. no carrying). Next, average GSI score, witnessing violence, and experiencing violence were compared separately across the 2 gun-carrying groups at each follow-up.

Next, a series of binary logistic regression models predicting gun carrying during each follow-up period were fit at each time point. With each model, GSI score, experiencing violence, and witnessing violence were entered in successive stages to allow for a comparison of model fit and to determine changes in coefficients as predictors were added. A likelihood ratio test was used to assess the degree to which the addition of experiencing violence and witnessing violence improved model fit at each time point. In addition, the stability of the relationship between gun carrying and GSI score over time was examined by documenting the predictive probability of carrying based on low versus high scores on the GSI, stratified by exposure to violence across all stages of data collection.

The multiple imputation procedure in SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM) was used to impute missing data and assess whether they influenced the multivariate analyses. Multiple imputation replicates the incomplete data set multiple times by replacing the missing data in each replicate with plausible values drawn from an imputation model. The linear regression method was automatically selected by SPSS as the best imputation method for handling the missing data. Age, race/ethnicity, study site, GSI score, experiencing violence, and witnessing violence were included as independent variables in the imputation models. Ten imputed data sets were created. The binary logistic regression models were performed on each complete data set separately.

Results

Descriptive and Bivariate Analyses

Information on the full sample and the samples from the 2 study sites is shown in Table 1. A large percentage (72.9%) of Philadelphia participants (n = 605) were African American, and a large percentage (55.4%) of Phoenix participants (n = 565) were Hispanic. The average age of the participants was 16.05 years (SD, 1.16; range, 14 to 19 years) at the baseline assessment and 18.02 years (SD, 1.14; range, 16 to 21 years) at the fourth follow-up assessment. Youths from Philadelphia were slightly older than those from Phoenix. The average educational grade completed among all youths was eighth grade, with those from Philadelphia reporting higher grade completion. After controlling for age, we found no significant difference in grade completion across the study sites (P = 0.40).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Sample at Baseline, by Study Site*

| Variable | All Participants | Philadelphia | Phoenix | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 1170) | (n = 605) | (n = 565) | ||

| Race/ethnicity, % | <0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 19.2 | 10.4 | 28.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 42.1 | 72.9 | 9.2 | |

| Hispanic | 34.0 | 14.0 | 55.4 | |

| Other | 4.6 | 2.6 | 6.7 | |

| Mean age (SD), y | 16.05(1.16) | 16.15 (1.22) | 15.94(1.08) | 0.002 |

| Mean educational grade completed (SD) | 8.04(1.27) | 8.13 (1.26) | 7.93 (1.28) | 0.009 |

| Mean age at first arrest (SD), y | 13.75(1.98) | 13.82 (1.82) | 13.68 (2.15) | 0.24 |

| Mean prior arrests (SD), n | 4.42 (4.89) | 4.18 (3.97) | 4.69 (5.71) | 0.075 |

| Ever carried a gun, % | 51.1 | 50.0 | 52.7 | 0.36 |

| Mean Exposure to Violence Inventory score (SD) | ||||

| Experienced | 1.64(1.47) | 1.49 (1.38) | 1.79 (1.53) | <0.001 |

| Witnessed | 3.85(1.93) | 4.23 (1.73) | 3.44 (2.05) | <0.001 |

| Total | 5.49 (2.98) | 5.72 (2.68) | 5.24 (3.27) | 0.005 |

| Mean Global Severity Index score (SD) | 0.53(0.51) | 0.50 (0.49) | 0.56 (0.54) | 0.025 |

Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Although the proportion of males found guilty of a drug charge who were invited to participate was capped at 15%, reported substance use among participants was high, with only 9.3% reporting no prior use of alcohol or drugs at the baseline assessment. Specifically, 84.6% of participants reported using marijuana, 80.4% reported using alcohol, 26.8% reported using hallucinogens, 22.0% reported using cocaine, 20.1% reported using sedatives, 15.3% reported using ecstasy, 14.6% reported using stimulants, 13.3% reported using inhalants, and 7.3% reported using opiates.

Average age at first arrest, average number of previous arrests, and prevalence of gun carrying were similar for participants in Philadelphia and Phoenix (Table 1). Among youths who reported carrying a gun, 56.6% (n = 328) reported it during 1 of the study periods, 25.0% (n = 145) reported it during 2 periods, 10.9% (n = 63) reported it during 3 periods, 5.9% (n = 34) reported it during 4 periods, and 1.9% (n = 9) reported it during all 5 periods. White youths (40.0%) were slightly less likely to report carrying a gun than African American youths (52.5%), Hispanic youths (51.0%), and biracial youths or those from other ethnicities (50.9%) (P =0.016). Age was related to carrying at the baseline assessment, with an older average age among those who reported carrying a gun at baseline (mean, 16.20 years [SD, 1.17]) than those who did not (mean, 15.96 years [SD, 1.13]) (P = 0.001). In all of the multivariate models, both race/ethnicity and age were included as control variables.

At the baseline assessment, participants from Philadelphia scored slightly higher on the GSI than those from Phoenix. On average, Phoenix youths reported more personal experiences of violence, whereas Philadelphia youths reported witnessing violence at a higher rate. Based on these observed differences, study site was also included in the multivariate analyses in order to investigate the predictive value of psychological distress and exposure to violence on gun carrying across the 2 populations.

Next, we considered the bivariate associations between the key independent and dependent variables related to the study hypotheses. At the baseline assessment and each follow-up assessment, youths who reported carrying a gun had significantly higher GSI scores than those who did not report carrying a gun (Table 2). In addition, rates of experiencing and witnessing violence were significantly higher among those who reported carrying a gun at all stages of data collection.

Table 2.

Bivariate Analyses of Association Between Gun Carrying and Global Severity Index and Exposure to Violence Inventory Scores

| Measure, by Time Point | Gun Carriers | Noncarriers | Mean Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Mean Global Severity Index score (SD) | 0.64(0.56) | 0.49 (0.49) | 0.14(0.08–0.21) |

| Mean Exposure to Violence Inventory score (SD) | |||

| Experienced | 2.36(1.50) | 1.34(1.50) | 1.08 (0.84–1.19) |

| Witnessed | 4.75(1.60) | 3.48(1.94) | 1.27 (1.04–1.50) |

| 6 mo | |||

| Mean Global Severity Index score (SD) | 0.57 (0.48) | 0.43(0.41) | 0.14 (0.06–0.22) |

| Mean Exposure to Violence Inventory score (SD) | |||

| Experienced | 0.97 (1.22) | 0.18 (0.52) | 0.80 (0.68–0.91) |

| Witnessed | 2.69(1.89) | 1.00(1.25) | 1.68 (1.44–1.93) |

| 12 mo | |||

| Mean Global Severity Index score (SD) | 0.62 (0.53) | 0.41 (0.47) | 0.21 (0.12–0.30) |

| Mean Exposure to Violence Inventory score (SD) | |||

| Experienced | 0.83(1.03) | 0.14 (0.46) | 0.70 (0.60–0.80) |

| Witnessed | 2.79(1.76) | 0.92 (1.29) | 1.87 (1.62–2.12) |

| 18 mo | |||

| Mean Global Severity Index score (SD) | 0.49 (0.44) | 0.37 (0.42) | 0.12 (0.03–0.20) |

| Mean Exposure to Violence Inventory score (SD) | |||

| Experienced | 0.82 (1.01) | 0.13 (0.46) | 0.68 (0.51–0.78) |

| Witnessed | 2.60(1.82) | 0.79(1.20) | 1.81 (1.57–2.04) |

| 24 mo | |||

| Mean Global Severity Index score (SD) | 0.58 (0.53) | 0.36 (0.43) | 0.05 (0.12–0.31) |

| Mean Exposure to Violence Inventory score (SD) | |||

| Experienced | 0.64 (0.98) | 0.11 (0.40) | 0.53 (0.44–0.63) |

| Witnessed | 2.47 (1.87) | 0.64(1.09) | 1.83 (1.60–2.05) |

Multivariate Analysis

Table 3 displays the results of the multivariate analyses at the 4 follow-up assessments, with gun carrying predicted by GSI score, experiencing violence, and witnessing violence measured at the previous time point while controlling for study site, race/ethnicity, age, and proportion of time spent on the streets. As shown in Table 3, GSI score was a significant predictor of carrying at 3 of the 4 assessments. The increased odds of carrying ranged from 1.36 to 2.29 for each unit increase in GSI score. The results of the likelihood ratio change tests, in which we estimated 2 models and compared the fit of one with that of the other, showed that the addition of experiencing violence to the model at each time point resulted in a significant improvement in model fit. After we controlled for experiencing violence in the models, the odds of carrying predicted by GSI score were diminished, ranging from 0.83 to 1.90 for each unit increase in the score. Exposure to violence was a significant predictor of carrying at all 4 stages, with increased odds ranging from 1.63 to 1.87 for each unit increase in experiencing violence. In the final model for each time point, the results of the likelihood ratio change tests showed that the addition of witnessing violence resulted in a significant improvement in model fit. After we controlled for witnessing violence at each time point, the odds of carrying predicted by GSI score were further diminished and the score was no longer a significant predictor. Witnessing violence was a significant predictor of carrying at all 4 stages, with increased odds ranging from 1.43 to 1.59 for each unit increase.

Table 3.

Summary of Binary Logistic Regression Analyses Predicting Gun Carrying at Each Follow-up Assessment*

| Variable | Incremental Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | 24 mo | |

| Model 1 | ||||

| Global Severity Index score | 1.36(0.95–1.94) | 2.07 (1.35–3.19)‡ | 1.55 (1.07–2.27)† | 2.29 (1.46–3.61)§ |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Global Severity Index score | 0.83(0.55–2.16) | 1.66 (1.05–2.62)† | 1.28 (0.85–1.94) | 1.90 (1.18–3.07)‡ |

| Exposure to Violence Inventory score (experienced) | 1.87 (1.61–2.16)§ | 1.63 (1.31–2.04)§ | 1.85 (1.40–2.44)§ | 1.74 (1.32–2.29)§ |

| Model 3 | ||||

| Global Severity Index score | 0.77 (0.65–1.84) | 1.61 (0.99–2.58) | 1.07 (0.69–1.68) | 1.61 (0.97–2.68) |

| Exposure to Violence Inventory score (experienced) | 1.53 (1.30–1.81)§ | 1.15(0.88–1.50) | 1.29 (0.95–1.75) | 1.18 (0.87–1.61) |

| Exposure to Violence Inventory score (witnessed) | 1.46 (1.25–1.70)§ | 1.43 (1.24–1.64)§ | 1.46 (1.27–1.68)§ | 1.59 (1.36–1.85)§ |

Study site, age, race/ethnicity, and proportion of time spent on the streets were included as control variables in all models.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

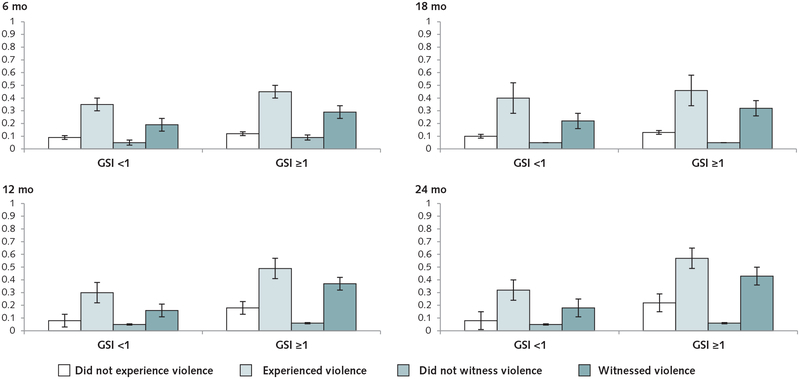

Predicted probabilities of gun carrying based on higher and lower GSI scores across the 4 follow-up assessments are shown in the Figure. The probabilities were stratified by exposure to violence (experienced or witnessed) and provide a clearer picture of the relationship among carrying, psychological distress, and exposure to violence. Across all 4 stages, the probability of carrying was highest among youths experiencing higher levels of psychological distress in combination with exposure to violence.

Figure. Predictive probabilities of gun carrying based on high vs. low scores on the GSI, stratified by exposure to violence at each follow-up assessment.

Error bars represent 95% CIs. Control variables included study site, age, race/ethnicity, and proportion of time spent on the streets. GSI = Global Severity Index.

Finally, we used the multiple imputation procedure to determine the effect of missing data on the results of the multivariate analyses. Apart from data missing due to attrition, only the GSI variable had greater than 1% missing values at any stage of data collection. For this variable, fewer than 1% of the missing values were due to incomplete interviews; other missing values (ranging from 6.8% to 26.7%) were caused by tests that were invalid due to an inadequate number of responses to items on any of the 9 BSI subscales, preventing computation of the GSI score. The analyses of the original data and the imputed data provided the same results. The results reported here are from analyses of the original data. Results using imputed data are available on request.

Discussion

Our findings highlight the importance of prevention and intervention strategies aimed at certain vulnerable subpopulations of people who may experience heightened violence as a victim, a witness, or both (32). Specifically, the results of this study suggest that psychological distress and gun carrying among serious youth offenders may be influenced by exposure to violence (either experiencing or witnessing it). The study consistently detected an association between psycho logical distress and gun carrying at various points; however, when we accounted for exposure to violence, the association was repeatedly diminished.

When strategies to reduce gun carrying and gun violence among vulnerable male youths are being considered, prevention and intervention efforts that focus on dealing with psychological distress after victimization and that are consistent with programming rooted in trauma-informed care may be most effective (32). This recommendation is in line with a recent study of youths with high exposure to trauma and violence who were experiencing a paradoxical combination of emotional numbing and hypervigilance—a “fatalistic form of PTSD” (33). Having grown desensitized to the threat of violence, participants no longer feared it because an early violent death seemed inevitable to them (33). Extreme risk-taking behaviors, such as gun carrying, commonly observed in gang-involved inner-city youths may be a form of suicidal behavior stemming from repeated exposure to violence (34, 35).

Currently, assessment for trauma-related psychological distress is not a standard of care in emergency departments, where many vulnerable minority youths affected by trauma and violence seek treatment (32). Concerted efforts, such as the Defending Childhood Initiative (36), are being made to respond to the detrimental emotional and social effects of exposure to violence among U.S. youths, and some have called for renewed efforts by health professionals to address the trauma stemming from exposure to violence by screening all youths who visit the emergency department to be treated for violent injuries and referring those experiencing psychological distress to appropriate providers (37).

Although the study findings add to our understanding of the potential influence of psychological distress and exposure to violence on gun carrying, the sample was limited to males who are serious youth offenders and is not representative of all adolescents. As a result, the generalizability of the findings is limited to male, justice-involved adolescents; however, this sub-population is precisely the group that is at greatest risk for future violence. In addition, nearly half of participants had started carrying a gun before study enrollment, so precarrying psychological symptoms and exposure to violence could not be fully captured. Furthermore, we did not explore other factors that may influence gun carrying, such as accessibility, community influences, employment, or peer behavior.

In conclusion, like other work in this area (30), these results do not provide strong support for psychological symptoms alone as markers of increased risk for violence-related behaviors, such as gun carrying (10, 22). Rather, the results suggest that pathways to gun carrying are complex. Establishing firmer restrictions on youth accessibility to guns alone has been shown to be an insufficient remedy for the unacceptably high rate of gun-related deaths among African American and Hispanic youths (1, 5, 38). Our findings indicate that access to trauma-informed treatment to address repeated exposure to violence and its psychological aftermath may be a critical element in combatting gun carrying and gun violence among high-risk, vulnerable adolescents.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Funding Source

The investigators received no funding for this study.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest. Forms can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M16-1648.

Reproducible Research Statement: Study protocol: Available from Dr. Reid (jareid2@usf.edu). Statistical code: Not available. Data set: Available at www.pathwaysstudy.pitt.edu.

References

- 1.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012; 61:1–162. [PMID: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branas CC, Richmond TS, Culhane DP, Ten Have TR, Wiebe DJ. Investigating the link between gun possession and gun assault. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:2034–40. [PMID: ] doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loughran TA, Reid JA, Collins ME, Mulvey EP. Effect of gun carrying on perceptions of risk among adolescent offenders. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:350–2. [PMID: ] doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J. Bullying and weapon carrying: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:714–20. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heron M Deaths: leading causes for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;62:1–96. [PMID: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spano R, Bolland J. Disentangling the effects of violent victimization, violent behavior, and gun-carrying for minority inner-city youth living in extreme poverty. Crime Delinq. 2013;59:191–213. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster DW, Gainer PS, Champion HR. Weapon carrying among inner-city junior high school students: defensive behavior vs aggressive delinquency. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1604–8. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esselmont C Carrying a weapon to school: the roles of bullying victimization and perceived safety. Deviant Behav. 2014;35:215–32. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilcox P, May DC, Roberts SD. Student weapon possession and the “fear and victimization hypothesis”: unraveling the temporal order. Justice Q. 2006;23:502–29. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher CE, Lieberman JA. Getting the facts straight about gun violence and mental illness: putting compassion before fear. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:423–4. [PMID: ] doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodges HJ, Scalora MJ. Challenging the political assumption that “Guns don’t kill people, crazy people kill people!” Am J Ortho-psychiatry. 2015;85:211–6. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1037/ort0000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swanson JW, Sampson NA, Petukhova MV, Zaslavsky AM, Appelbaum PS, Swartz MS, et al. Guns, impulsive angry behavior, and mental disorders: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Behav Sci Law. 2015;33:199–212. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/bsl.2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loeber R, Burke JD, Mutchka J, Lahey BB. Gun carrying and conduct disorder: a highly combustible combination? Implications for juvenile justice and mental and public health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:138–45. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green DL, Diaz N. Predictors of emotional stress in crime victims: implications for treatment. Brief Treat Crisis Interv. 2007;7:194–205. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R. Mental health needs of crime victims: epidemiology and outcomes. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:119–32. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddow JL. Residual effects of repeated bully victimization before the age of 12 on adolescent functioning. J Sch Violence. 2006; 5:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vitaro F, Boivin M, Tremblay RE. Peers and violence: a two-sided developmental perspective In: Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, Waldman ID, eds. The Cambridge Handbook of Violent Behavior and Aggression. New York: Cambridge Univ Pr; 2007:361–87. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ericson N Addressing the Problem of Juvenile Bullying. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nansel TR, Overpeck M, Pilla RS, Ruan WJ, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA. 2001;285:2094–100. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vossekuil B, Fein RA, Reddy M, Borum R, Modzeleski W. The Final Report and Findings of the Safe School Initiative. Washington, DC: U.S. Secret Service and U.S. Department of Education; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metzl JM, MacLeish KT. Mental illness, mass shootings, and the politics of American firearms. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:240–9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin R Mental health reform will not reduce US gun violence, experts say. JAMA. 2016;315:119–21. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shetgiri R, Boots DP, Lin H, Cheng TL. Predictors of weapon-related behaviors among African American, Latino, and white youth. J Pediatr. 2016;171:277–82. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.David-Ferdon C, Simon TR, Spivak H, Gorman-Smith D, Savannah SB, Listenbee RL, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC grand rounds: preventing youth violence. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:171–4. [PMID: ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulvey EP. Research on Pathways to Desistance [Maricopa County, AZ and Philadelphia County, PA]: Subject Measures, 2000–2010. (Research on Pathways to Desistance Series). Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2012. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR34488.v2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mulvey EP, Steinberg L, Fagan J, Cauffman E, Piquero AR, Chassin L, et al. Theory and research on desistance from antisocial activity among serious adolescent offenders. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2004;2:213 [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schubert CA, Mulvey EP, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Losoya SH, Hecker T, et al. Operational lessons from the Pathways to Desistance Project. Youth Violence Juv Justice. 2004;2:237 [PMID: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huizinga D, Esbensen FA, Weiher AW. Are there multiple paths to delinquency? J Crim Law Criminol. 1991;82:83–118. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PMID: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skeem JL, Schubert C, Odgers C, Mulvey EP, Gardner W, Lidz C. Psychiatric symptoms and community violence among high-risk patients: a test of the relationship at the weekly level. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:967–79. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Selner-O’Hagan MB, Kindlon DJ, Buka SL, Raudenbush SW, Earls FJ. Assessing exposure to violence in urban youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39:215–24. [PMID: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ursano RJ, Benedek DM, Engel CC. Trauma-informed care for primary care: the lessons of war. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:905–6. [PMID: ] doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richardson JB Jr, Brown J, Van Brakle M. Pathways to early violent death: the voices of serious violent youth offenders. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e5–16. [PMID: ] doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Putnam FW. Impact of trauma on child development. Juv Fam Court J. 2006;57:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaffer JN, Ruback RB. Violent victimization as a risk factor for violent offending among juveniles. Juvenile Justice Bulletin. 2002. Accessed at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/195737.pdf on 13 July 2016.

- 36.Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Office of Justice Programs; U.S. Department of Justice. Defending Childhood Initiative. 2016. Accessed at www.defendingchildhood.org on 22 December 2016.

- 37.Gambacorta D Are doctors the key to ending Philly gun violence? Philadelphia Magazine. 17 April 2016. Accessed at www.phillymag.com/news/2016/04/17/chop-youth-violence-prevention/#WRMI4VeB6Aov6FDm.03 on 15 December 2016.

- 38.Webster DW, Wintemute GJ. Effects of policies designed to keep firearms from high-risk individuals. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:21–37. [PMID: ] doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]