Abstract

Background:

Hospital-acquired infection (HAI) is one of the most common complications occurring in a hospital setting. Although previous studies have demonstrated the application of data-driven Six Sigma DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control) methodology in various health-care settings, no such studies have been conducted on HAI in the Saudi Arabian context.

Objective:

The purpose of this research was to study the effect of the Six Sigma DMAIC approach in reducing the HAI rate at King Fahd Hospital of the University, Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia.

Methods:

Historical data on HAI reported at inpatient units of the hospital between January and December 2013 were collected, and the overall HAI rate for the year 2013 was determined. The Six Sigma DMAIC approach was then prospectively implemented between January and December 2014, and its effect in reducing the HAI rate was evaluated through five phases. The incidence of HAI in 2013 was used as the problem and a 30% reduction from 4.18 by the end of 2014 was set as the project goal. Potential causes contributing to HAI were identified by root cause analysis, following which appropriate improvement strategies were implemented and then the pre- and postintervention HAI rates were compared.

Results:

The overall HAI rate was observed as 4.18. After implementing improvement strategies, the HAI rate significantly reduced from 3.92 during the preintervention phase (first quarter of 2014) to 2.73 during the postintervention phase (third quarter of 2014) (P < 0.05). A control plan was also executed to sustain this improvement.

Conclusion:

The results show that the Six Sigma “DMAIC” approach is effective in reducing the HAI rate.

Keywords: “Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control” hand hygiene; hospital-acquired infection rate; Six Sigma

INTRODUCTION

Hospital-acquired infection (HAI) in a health-care setting is one of the major causes of death and increased morbidity among hospitalized patients. It prolongs the hospital stay of affected patients and increases the cost of patient care.[1] In Europe, HAI affects 1 of 10 hospitalized patients and causes nearly 5000 annual deaths. In Saudi hospitals, the overall rate of HAIs was reported to be 8% in 2003 and 4.5 per 1000 discharged patients in 2004.[2,3,4] Likewise, in hospitals located at Taif, Saudi Arabia, the nosocomial infection rate was found to be 1.86 and 2.09 for 2010 and 2011, respectively.[5] HAI can occur within 48 h of hospital admission, 3 days of discharge or 30 days of an operation. The most common types of HAIs are bloodstream infection, ventilator-associated pneumonia, urinary tract infection and surgical site infection. The viral, bacterial or fungal pathogens of such infections are mostly resistant to at least one commonly used antibiotic. Of these, there are several multidrug-resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant S. aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci, which are becoming increasingly problematic, particularly in the critical care setting, and creating challenges in the management of HAIs.[6]

HAI leads to emotional stress, considerable increase in costs due to the increased length of hospital stay, functional disability and, in some cases, death.[7,8,9,10,11,12] In addition, increased use of drugs, need for isolation as well as the additional use of laboratory and other diagnostic studies also contribute to the increase in costs. Therefore, to ensure patient safety and reduce the cost of patient care, it is imperative to take necessary preventive measures against HAI in hospital settings. Some of these preventive measures include proper handling and disposal of sharp instruments (e.g., needles) and biomedical waste, sterilization of instruments, food and water precautions, surface sanitation, periodical medical checkup and vaccination for health-care workers, training programs, hand hygiene protocol, use of personal protective equipment (PPE), reduction in the number of visitors and isolation rooms.[13,14] Lack of hand hygiene compliance among health-care workers has been found to be the main source of HAIs.[15] Further, it is observed that a 20% increase in hand hygiene compliance reduces the rate of HAI by 40%.[16,17]

In the United States, approximately 2 million patients annually suffer from HAIs and nearly 90,000 are estimated to die.[18] Therefore, there is an urgent need to address potential risk factors and gaps in hospital processes, which in turn would reduce the occurrence of HAIs. Traditionally, measures toward reduction of HAI focus on individual performances and their errors as well as on addressing gaps in hospital processes, especially focusing on postimplementation monitoring.

Although previous studies have demonstrated the application of Six Sigma DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control) methodology in reducing HAIs, no such studies have been conducted on HAI in the Saudi Arabian context.[19,20,21] To fill this gap, the present research was conducted to study the effect of Six Sigma DMAIC approach in reducing the HAI rate at the King Fahd Hospital of the University (KFHU), Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia.

METHODS

Design and setting

This prospective study was conducted at KFHU, Al-Khobar, Saudi Arabia. First, the historical data on HAI reported at the hospital's inpatient units between January and December 2013 were collected from the hospital's Infection Control Committee, and the overall HAI rate for the year 2013 was determined. The Six Sigma DMAIC approach was then implemented between January and December 2014, and its effect in reducing the HAI rate was evaluated. Ethical approval for this study was was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, Deanship of Scientific Research, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, on May 4, 2015 (IRB No.: IRB-2014-22-225).

Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control model

The five effective phases of the Six Sigma DMAIC model are described as follows.

Define Phase

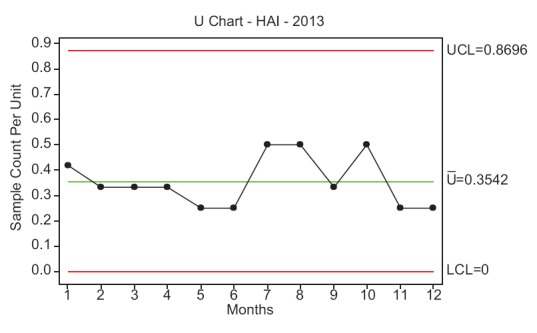

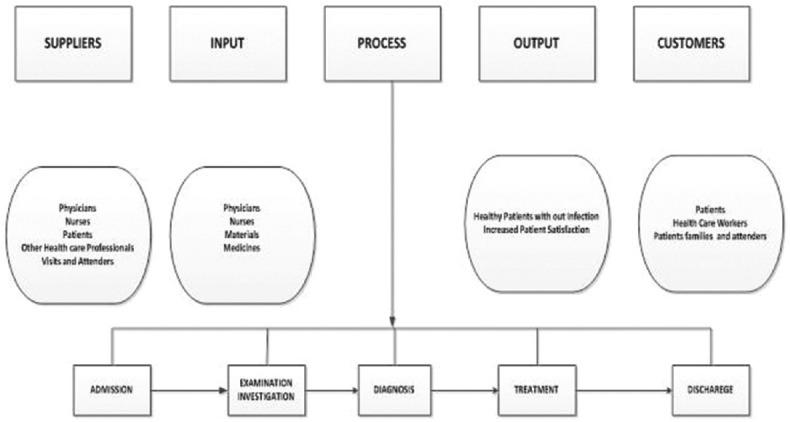

First, a project charter was prepared to define the problem, scope of the project, its goals and team members involved [Table 1]. A U-chart was used to study the data for 2013 [Figure 1]. Based on the historical data, the incidence of HAI in 2013 was defined as the problem and a 30% reduction from 4.18 by the end of 2014 was set as the project goal. Accordingly, an internal multidisciplinary team was formed, and the patient-handling process was studied using the SIPOC (suppliers, inputs, process, outputs and customers) tool [Figure 2]. Several types of infections were then identified and stratified into various categories.

Table 1.

Description of project charter

| Project charter | |

|---|---|

| Project name | Study of effect of applying Six Sigma (DMAIC) methods in reducing HAI rate in a university hospital |

| Resource plan | Champion - Principal investigator Black belt - Coinvestigator Process owner - Vice dean of clinical affairs |

| Problem statement | In 2013, the number of patients prone to HAI was high in KFHU. This could negatively affect the quality of patient care services and challenge patient safety |

| Goal statement | Reduce the HAI rate by 30% (i.e., from 4.18 to <3) by the end of December 2014 |

| Intangible benefits | Enhanced patient safety Increased patient satisfaction Improved public image and reputation of the university hospital The impact of project outcomes on the cost of patient care is not to be addressed, as the hospital is entirely managed through government funding |

| Team members | Representatives belonging to the following units: infection control, medicine, nursing, laboratory, pulmonary, environmental systems, epidemiology, radiology, quality and safety directorate, finance, central sterile services department, housekeeping and food and water supply |

| Scope | To reduce the HAI rate at all inpatient units of KFHU by the end of December 2014 |

| High-level project milestone | This project would carry through the five phases of DMAIC extending over a period of 12 months from January to December 2014 |

DMAIC – Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control; HAI – Hospital-acquired infection; KFHU – King Fahd Hospital of the University

Figure 1.

Control chart (U-chart) showing the incidence of hospital-acquired infection during the year 2013

Figure 2.

Suppliers, inputs, process, outputs and customers diagram of the patient-handling process adopted in King Fahd Hospital of the University

Measure Phase

Investigators developed a data collection plan and gathered data to stratify baseline performance. A check sheet was developed to identify any potential HAIs among patients who were hospitalized during the first quarter of 2014 [Supplementary Appendix 1, online only]. The preintervention HAI rate was calculated by dividing the number of HAIs reported in the specified period with the total number of patient-days for the same period, the result of which was then multiplied by 1000. HAI rate at KFHU during the first quarter of 2014 was measured. Subsequently, a baseline sigma for the occurrence of HAI at KFHU was calculated [Table 2].

Table 2.

Contributing factors of hospital-acquired infection

| Potential causes contributing to the occurrence of HAI |

|---|

| Poor knowledge and application of basic infection control measures |

| Overcrowding |

| Inefficient implementation of policies and procedures across the hospital |

| Insufficient knowledge about blood transfusion safety |

| Needles stick injuries/blood and fluid exposure (mucocutaneous occupational exposures in health-care workers) |

| Inadequate environmental hygienic conditions and waste disposal |

| Poor hand hygiene practices adopted by the health-care workers |

| Factors contributing to health-care workers’ poor adherence to hand hygiene |

| Lack of knowledge on guidelines/protocols |

| Busy/insufficient time |

| Sinks are inconveniently located/shortage of sinks |

| Lack of soap and paper towels |

| Understaffing/overstaffing |

| Lack of scientific information regarding the definitive impact of improved hand hygiene on health care-associated infection rate |

| Wearing gloves with a belief that glove use obviates the need for hand hygiene |

HAI – Hospital-acquired infection

Analyze Phase

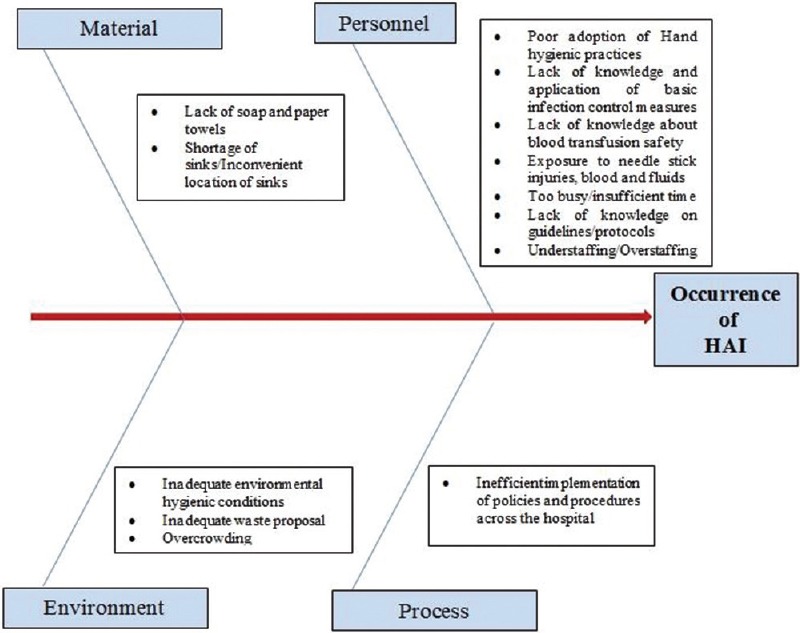

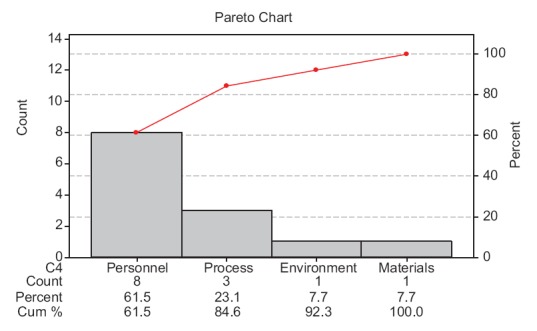

A root cause analysis (RCA) was carried out for each reported HAI case, and a checklist was prepared to find their potential causes. A cause–effect diagram was made to identify the potential causes of HAI [Figure 3] and is listed in Table 3. Further, a Pareto analysis was performed to find the vital few causes contributing to the trivial many [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Cause–effect diagram of potential causes of hospital-acquired infection at King Fahd Hospital of the University

Table 3.

Various improvement strategies to overcome the causes for hospital-acquired infection

| Improvement strategies |

|---|

| Developing and implementing infection control policies and procedures |

| Preparation and distribution of infection control booklet |

| Training programs on infection control |

| Developing and implementing of hand hygiene champion posters |

| Creation of a screensaver message on hand hygiene on all computer monitors with periodic changes |

| Creating and implementing a housekeeping hand hygiene support verification as part of the daily cleaning checklist |

| Developing a patient/visitor hand hygiene brochure and education/awareness plan and placing them in the admission packet and family lounges |

| Conducting an environmental assessment with staff and physicians for location/accessibility of hand hygiene supports and implementing a master plan for best locations on the unit as well as on portable equipment |

| Infection control policies and procedures |

| Definitions of health care-associated infections |

| Vancomycin-resistant enterococci management |

| Management of needlestick injuries/blood and fluid exposure |

| Disinfection and sterilization of patient care equipment |

| Immunization program |

| Training programs |

| Hand hygiene compliance |

| Standard precaution and isolation precaution |

| Proper use of PPE |

| Health-care worker immunization |

| Notifiable diseases/conditions to Ministry of Health |

| Types of biomedical waste and its management |

| Management of exposure to blood and body fluids spills |

PPE – Personal protective equipment

Figure 4.

Pareto chart

Improve Phase

Based on the cause–effect diagram and Pareto analysis, the internal multidisciplinary team framed the appropriate improvement strategies through various brainstorming sessions with stakeholders of KFHU [Table 4]. Such strategies were implemented for a period of 3 months (third quarter of 2014) at KFHU and postintervention HAI rate was then calculated. Further, the effectiveness of these strategies was studied by comparing the pre- and postintervention HAI rates.

Table 4.

Baseline sigma showing the occurrence of hospital-acquired infection during the first quarter of 2014

| Process Sigma components | Output/result |

|---|---|

| Number of defects opportunities per unit (O) (inpatients served in the hospital without HAI from January 2014 to March 2014) | O = 1 |

| Total number of inpatient’s days at KFHU from January 2014 to March 2014 | n = 3297 |

| Number of patients prone to HAI during the same time period (D) | D = 13 |

| DPO = (D/O) × n | 0.0040 |

| Yield (1−DPO) ×100 | 99.60 |

| Process Sigma | σ = 4.16 |

DPO – Defects per opportunity; D – Defects; O – Opportunity; HAI – Hospital-acquired infection; KFHU – King Fahd Hospital of the University

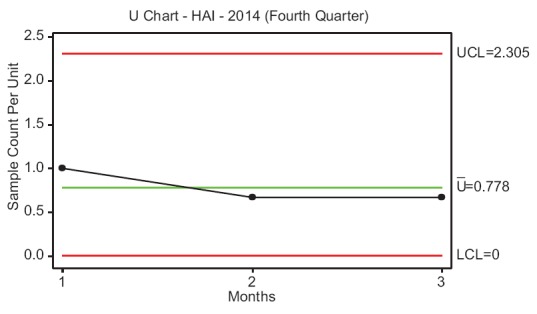

Control Phase

A control plan was executed by the Directorate of Quality and Safety of KFHU to statistically monitor the process and sustain the improvement obtained. HAI rate pertaining to the fourth quarter of 2014 was monitored, and a U-chart was used to check whether the process was under control and the improvement obtained could be sustained [Figure 5]. Further, the multidisciplinary team also conducted a periodic audit during December 2014 among the hospital employees to check their hand hygiene compliance and proper utility of all PPEs, and a random adherence rate was estimated.

Figure 5.

Control chart of hospital-acquired infection rate during the fourth quarter of 2014

Tools and techniques

Following are the various Six Sigma tools and techniques that were used to implement the DMAIC model in this study: project charter; SIPOC; control chart (U-chart); RCA; cause and effect diagram and Pareto analysis.

Data analysis

Minitab (Minitab Inc, State College, PA, USA) and SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were used for data analysis. The HAI rates between the first and third quarter of 2014 were compared using the t-test. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

To define the problem, the incidence of HAI at KFHU during the year 2013 was reported as 4.18 [Figure 1]. Further, HAI rates measured in January, February and March 2014 (first quarter of 2014) were 4.31, 3.87 and 3.54, respectively, with a mean of 3.92. Subsequently, the baseline sigma for the occurrence of HAI was calculated as 4.16 σ [Table 4]. Pareto chart revealed that issues related to the category of health-care personnel highly influenced the occurrence of HAI at KFHU [Figure 4]. Taking into consideration findings of the cause–effect diagram and Pareto analysis, various improvement strategies were framed and implemented during the third quarter of 2014. After implementation of such strategies, it was observed that the HAI rate had significantly reduced from 3.92 during the preintervention phase (first quarter of 2014) to 2.73 during the postintervention phase (third quarter of 2014) (P ≤ 0.05) [Table 5]. In the Control Phase, the HAI rate during the fourth quarter of 2014 was reported as 2.4, and the U-chart indicated that the process was under control and that sustained improvement had been achieved. From the random sample estimation of hand hygiene practice and adherence by employees toward proper utilization of PPEs during a periodic audit, it was found that 85% of employees adhered to such practices.

Table 5.

Difference between the hospital-acquired infection rates in the pre- and postintervention phases

| Period | Mean | SD | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention phase | 3.92 | 0.40 | 35.00 | 0.001* |

| Postintervention phase | 2.73 | 0.35 |

*Significant at the 0.05 level. SD – Standard deviation

DISCUSSION

The present work studied the impact of applying the Six Sigma DMAIC approach in reducing the HAI rate at KFHU.

In US hospitals, HAIs account for an estimated 1.7 million infections and 99,000 associated deaths each year,[22,23] and the overall annual direct medical cost is approximately USD35.7–45 billion.[24] In our study, HAI reported at KFHU for 2013 was 4.18, which was higher than that reported by Pennsylvania Department of Health (2.45 rate per 1000 patient days).[25] It is anticipated that reduction in HAI rate will eventually enhance patient safety, increase patient satisfaction, decrease mortality as well as reduce the length of stay and cost of patient care.

A few studies have demonstrated the utility of the Six Sigma approach in the health-care sector with a specific focus on catheter-related bloodstream infections, nosocomial urinary tract infections, MRSA infections and operating room throughput, surgery turnaround time, clinic appointment access, hospital discharge process, hand hygiene compliance, antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery, scheduling radiology procedures and meeting standards for cardiac medication administration.[19,20,21,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] However, to the best of our knowledge, in the Saudi Arabian context, this is the first-of-its-kind study describing the use of a Six Sigma model in reducing HAI rates.

This study was conducted through the five phases of DMAIC approach using different quality tools and techniques at each level. This approach helped the authors to define the appropriate goal, measure the data resources, analyze the possible causes, implement the improvement strategies and sustain the gains. During the Define Phase, the problem under investigation was clearly defined with respect to HAI incidence during the previous year, and a goal to reduce the HAI rate by 30% was set. During the Measure Phase, the HAI rate was measured as 3.92 and a baseline sigma calculation was made to measure the current performance level regarding the efficiency of infection control measures adopted at KFHU. This performance level was found to be lower than the performance indicated in the study by Drenckpohl et al., which attempted to reduce the incidence of breast milk administration errors in a neonatal intensive care unit.[33]

In the Analyze Phase, a RCA was carried out to determine the possible causes of each infectious case. After implementing the improvement strategies, the HAI rate reduced from 3.92 at the preintervention value to 2.73. This result is in accord with that of a previous study reporting a 30% decrease in nosocomial urinary tract infections after the application of the Six Sigma process improvement methodology.[20] Another study indicated a 76% reduction in central line-associated bloodstream infection in an 18-month period following the application of the Six Sigma DMAIC model at adult ICUs.[34]

During the Control Phase, a control plan was developed and implemented by the investigators to monitor and sustain the gains obtained during the Improve Phase. Most employees (85%) were found to have adhered to the hand hygiene practice and PPEs, the main components addressed during this phase. Similarly, a previous study has demonstrated that the compliance to such practices increased from 38% to 69% following the adoption of the hand washing routine; however, this increase in the adherence rate was not associated with detectable changes in the incidence of HAI.[35] In contrast, another study found the Six Sigma process to be effective in organizing the knowledge, opinions and actions of a group of professionals to implement the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's evidence-based hand hygiene practices in ICUs.[29] Despite these contradictory findings from the earlier study, our finding demonstrated that Six Sigma is an effective approach in reducing the HAI rate.

Limitations and recommendations

This study only focused on inpatient units of a university hospital in Saudi Arabia, excluding the HAI rates among outpatients. Thus, it is recommended to extend this study to focus on outpatient departments. A similar application of the Six Sigma approach can be performed in other hospital-related operations such as surgery turnaround time, clinic appointment access, antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery, radiology procedures and hospital bed availability. The cost-effectiveness of improved processes can be studied in future research.

CONCLUSION

Application of the Six Sigma DMAIC approach was found to be effective in reducing the HAI rates, thereby ensuring patient safety and satisfaction at KFHU, Dammam, Saudi Arabia. The DMAIC model described in this study may help hospital administrators and quality management personnel to identify implementation strategies and significantly reduce HAI rates in health-care settings and assist in sustaining the gains obtained.

Financial support and sponsorship

This project was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, during the academic year of 2013–2014.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to Deanship of Scientific Research, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, for funding this research project during the year 2014. The authors would like to specially thank the Infection Control Department, Nursing Department and Environment and Safety Team for their input in successful completion of First Six Sigma Project at KFHU, Saudi Arabia.

APPENDIX 1

Check sheet for analyzing the infectious cases

Age:

Patient ID:

Gender:

Weight:

Days in hospital:

Days in ICU

Procedures done: Therapeutic/Interventions antimicrobial use/Indication of antimicrobial (prophylactic-therapeutic)

Infection type:

Septicemia pneumonia upper respiratory tract ◻

Urinary tract infection ◻

Skin infection ◻

Fungal infection ◻

Others ◻

Signature of the Screening Member Date:

REFERENCES

- 1.McCormack JG, Barnes M. Nosocomial infections in a developing Middle East hospital. Infect Control. 1983;4:391–5. doi: 10.1017/s0195941700059816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inweregbu K, Dave J, Pittard A. Nosocomial infections. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2005;5:14–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balkhy HH, Cunningham G, Chew FK, Francis C, Al Nakhli DJ, Almuneef MA, et al. Hospital-and community-acquired infections: A point prevalence and risk factors survey in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10:326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abdel-Fattah MM. Surveillance of nosocomial infections at a Saudi Arabian military hospital for a one-year period. Ger Med Sci. 2005;3:Doc06. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabra MS, Abdel-Fattah MM. Epidemiological and microbiological profile of nosocomial infection in Taif hospitals, KSA (2010-2011) World J Med Res. 2012;7:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girou E, Stephan F, Novara A, Safar M, Fagon JY. Risk factors and outcome of nosocomial infections: Results of a matched case-control study of ICU patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157(4 Pt 1):1151–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9701129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponce-de-Leon S. The needs of developing countries and the resources required. J Hosp Infect. 1991;18(Suppl A):376–81. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(91)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plowman R, Graves N, Griffin M, Roberts JA, Swan AV, Cookson B, et al. London: Public Health Laboratory Service and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 1999. The Socio-economic burden of hospital-acquired infection. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wenzel RP. The Lowbury Lecture. The economics of nosocomial infections. J Hosp Infect. 1995;31:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(95)90162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittet D, Tarara D, Wenzel RP. Nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA. 1994;271:1598–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.20.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: Attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:725–30. doi: 10.1086/501572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wakefield DS, Helms CM, Massanari RM, Mori M, Pfaller M. Cost of nosocomial infection: Relative contributions of laboratory, antibiotic, and per diem costs in serious Staphylococcus aureus infections. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16:185–92. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Public Health Agency of Canada. Hand Hygiene Practices in Healthcare Settings. 2012. [Last accessed on 2016 Feb 02]. Available from: http://www.ipaccanada.org/pdf/2013-PHAC-Hand%20Hyg.iene-EN.pdf .

- 14.Provincial Infectious Diseases Advisory Committee. Routine Practices and Additional Precautions in All Health Care Settings. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care; 2012. Nov, [Last accessed on 2016 Jan 03]. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/eRepository/RPAP-All-HealthCare-Settings-Eng2012.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unnecessary Deaths: The Human and Financial Costs of Hospital Infections. 2008. [Last accessed on 2015 Dec 27]. Available from: http://www.hospitalinfection.org/ridbooklet.pdf .

- 16.McGeer A. Hand hygiene by habit. Infection prevention: Practical tips for physicians to improve hand hygiene. Ont Med Rev. 2007;74:31–2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donaldson L. Strengthening the patient's hand. London: Department of Health; 2006. Department of Health. Healthcare-associated infection. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone PW. Economic burden of healthcare-associated infections: An American perspective. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9:417–22. doi: 10.1586/erp.09.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankel HL, Crede WB, Topal JE, Roumanis SA, Devlin MW, Foley AB. Use of corporate Six Sigma performance-improvement strategies to reduce incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infections in a surgical ICU. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:349–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen BG. Reducing nosocomial urinary tract infections through process improvement. J Healthc Qual. 2006;28:W2-2-9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carboneau C, Benge E, Jaco MT, Robinson M. A lean Six Sigma team increases hand hygiene compliance and reduces hospital-acquired MRSA infections by 51% J Healthc Qual. 2010;32:61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2009.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of Healthcare-Associated Infections. [Last cited on 2010 Mar 12; Last accessed on 2016 Mar 06]. Available from: http://www.doh.dc.gov/page/healthcare-associated-infections .

- 23.Department of Health and Human Services. Action Plan to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections. 2009. Jun 22, [Last accessed on 2016 Feb 16]. Available from: http://www.doh.dc.gov/page/healthcare-associated-infections .

- 24.National Center for Preparedness, Detection and Control of Infectious Diseases Coordinating Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The Direct Medical Costs of Healthcare-Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals and the Benefits of Prevention. 2009. Mar, [Last accessed on 2016 Jan 21]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/hai/scott-ostpaper.pdf .

- 25.Pennsylvania Department of Health (PADOH) Report. Healthcare-Associated Infections in Pennsylvania. 2014. [Last accessed on 2016 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www.health.pa.gov/facilities/Consumers/Healthcare%20Associated%20Infection%20(HAI)/Documents/PennsylvaniaHAIReport2014-Final-20150923.pdf .

- 26.Adams R, Warner P, Hubbard B, Goulding T. Decreasing turnaround time between general surgery cases: A Six Sigma initiative. J Nurs Adm. 2004;34:140–8. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bush SH, Lao MR, Simmons KL, Goode JH, Cunningham SA, Calhoun BC. Patient access and clinical efficiency improvement in a resident hospital-based women's medicine center clinic. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:686–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vijay SA. Reducing and optimizing the cycle time of patients discharge process in a hospital using Six Sigma DMAIC approach. Int J Qual Res. 2014;8:169–82. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eldridge NE, Woods SS, Bonello RS, Clutter K, Ellingson L, Harris MA, et al. Using the Six Sigma process to implement the centers for disease control and prevention guideline for hand hygiene in 4 Intensive Care Units. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S35–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker BM, Henderson JM, Vitagliano S, Nair BG, Petre J, Maurer WG, et al. Six Sigma methodology can be used to improve adherence for antibiotic prophylaxis in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:140–6. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000250371.76725.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volland J. Quality intervenes at a hospital. Qual Prog. 2005;38:57. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elberfeld A, Goodman K, Van Kooy M. Using the Six Sigma approach to meet quality standards for cardiac medication administration. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2004;11:510–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drenckpohl D, Bowers L, Cooper H. Use of the Six Sigma methodology to reduce incidence of breast milk administration errors in the NICU. Neonatal Netw. 2007;26:161–6. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.26.3.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lori FB, Samantha M, Stephen C, Roopa KS, Fran W. New York: Using DMAIC as a Road Map to Approach Zero Central Line Infections. [Last accessed on 2016 Mar 15]. Available from: https://www.idsa.confex.com/idsa/2015/webprogram/Paper52953.html .

- 35.Rupp ME, Fitzgerald T, Puumala S, Anderson JR, Craig R, Iwen PC, et al. Prospective, controlled, cross-over trial of alcohol-based hand gel in Critical Care Units. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:8–15. doi: 10.1086/524333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]