Abstract

Melioidosis, a bacterial infection caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei is expanding in its endemicity around the world. Melioidosis most commonly infects adults with an underlying predisposing condition, mainly diabetes mellitus. Primary skin and soft tissue involvement is more common in younger patients. Almost every organ can be affected, but the most commonly affected organ is the lung followed by the spleen. Melioidosis has a wide range of radiological manifestations making it a mimicker. Diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion in patients with septicemia or a fever of unknown origin living in or with a travel history to endemic areas. We present a pictorial review of the radiological manifestations of melioidosis, which is a useful knowledge for radiologists to help arrive at an early diagnosis. In this pictorial review, we present the radiological manifestations chosen from 139 patients with culture proven melioidosis. Illustrated examples are chosen from our clinical experience of the past 15 years at the National University Hospital in Singapore.

Keywords: Abscess, Burkholderia infections, melioidosis

Abstract

ملخص البحث : يعانون من أمراض مزمنة كمرض السكري. وتصاب الأنسجة اللينة في المرضى الأصغر سنا. الجهاز التنفسي هو الأكثر إصابة يتبعه الطحال. للراعوم مجموعة واسعة من المظاهر الشعاعية مما يجعله مشابها لكثير من الأمراض. مما يجب استبعاد الحالات المشابهة كتسمم الدم أو الحمى غير معروفة السبب لدى القاطنين أو القادمين من المناطق التي يستوطن فيها المرض. في هذا الاستعراض يناقش الباحثان المظاهر الشعاعية المختلفة التي يمكن ان تساعد في التوصل إلى التشخيص المبكر والتي تم اختيارها من 931 مريضاً كانوا يعانون من الراعوم. تم اختيار أمثلة مهمة من خبرات الباحثين السريرية في المستشفى الجامعي الوطني في سنغافوره على مدى السنوات الخمس عشرة الماضية.

INTRODUCTION

Burkholderia pseudomallei, the cause of melioidosis, is endemic in Northern Australia and Southeast Asia.[1] It has a wide range of clinical manifestations, varying from asymptomatic infection to localized formation of the abscess to fulminating disease with multiple organ involvement and even death. It is almost impossible to diagnose it clinically. Hence, an awareness of the disease and knowledge of the various radiological manifestations may help in guiding and obtaining the appropriate diagnostic test to reach an early diagnosis. The lung is by far the most common organ to be involved, and may manifest as consolidation, abscesses, and multiple nodules with or without empyema. The spleen is the most common extrapulmonary organ to be involved.[2] A higher mortality rate is found in patients with pneumonia, disseminated, multiple organ involvement, or septicemia; compared to patients with single organ involvement without pneumonia.[3]

In this pictorial review, we present the radiological manifestations chosen from 139 patients with culture proven melioidosis. The examples are chosen from our 15 years of clinical experience at the National University Hospital in Singapore.

HISTORY AND NOMENCLATURE

Melioidosis is caused by free-living bacteria, B. pseudomallei, Gram-negative bacilli found in the natural environment (soil and surface water). First recognized in Burma in 1912 by Whitemore and Krishnaswami, it was called the Whitmore's disease.[4] In 1932, Stanton and Fletcher published their definitive monograph on the disease, which they named melioidosis (Greek, melis, a distemper of asses, eidos). This was because the disease clinically and pathophysiologically resembled glanders, a chronic debilitating disease of equines due to Pseudomonas mallei. The causative organism acquired several earlier names and was called Pseudomonas pseudomallei.[5] In 1992, Walter Burkholder named a new genus Burkholderia and moved seven species of Pseudomonas including pseudomallei into it. A number of additional related environmental bacterial species have been subsequently discovered and added to the Burkholderia genus.[6]

ROUTE OF TRANSMISSION

The organism enters the human host most commonly through a preexisting skin epithelial defect, and the majority of human cases are from percutaneous inoculation.[7] Inhalation and ingestion of causative bacteria are other known routes. Uncommon routes of transmission include near drowning, nosocomial or laboratory transmission, vertical transmission at childbirth, and sexual transmission.[7] The person-to-person route of transmission is very rare, and only standard infection control measures have been recommended for clinical care of patients with melioidosis.[8]

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Melioidosis occurs in Southeast Asia and Northern Australia as an endemic disease. Sporadic cases have increasingly been reported from tropical and subtropical countries mainly between latitudes 20°N and 20°S.[9]

There is a close association between rainfall and melioidosis, with increased exposure to muddy soils or surface water following the rains. Global expansion of the disease has been noted with increasing movement of people between countries. Therefore, melioidosis remains a risk for travelers to endemic areas.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSIS

Melioidosis mostly infects adults with a predisposing condition, mainly diabetes mellitus, which has been reported in 37-60% of patients. Other risk factors include alcoholism, renal disease, cirrhosis, chronic lung disease, thalassemia, cystic fibrosis, malignancy, steroid therapy, and other causes of immune suppression. However, melioidosis does not seem to be associated with HIV infection.[7] Healthy and immune competent individuals are still at risk of the infection, especially if the exposure load is heavy.

The clinical manifestations range from subclinical infection to fulminating disease with multiple organ involvement and even death. Definitive diagnosis is made by positive culture of the organism. The serodiagnostic test of melioidosis is indirect hemagglutination (IHA). However, IHA does not distinguish between patients with past exposure, latent infection or active melioidosis, but higher titer (>1:640) is suggestive of active disease.[9]

BODY SITES AND ORGAN INVOLVEMENTS

Almost every organ can be affected by melioidosis. Lungs, skin, and subcutaneous tissue; visceral organs such as the spleen and liver are commonly affected. Rare sites of involvement include: The central nervous system; bone and joints; cardiac and vascular systems. Although lymph nodes can be involved by B. pseudomallei, suppurative lymphadenitis is a rare presentation.[10]

IMAGING FINDINGS

Pulmonary melioidosis

The lung is the most common organ involved by melioidosis, with pneumonia as the most common clinical and radiological presentation accounting for about half of the cases of melioidosis reported in the larger series.[7] It is difficult to determine whether lung consolidation is a primary pneumonia or secondary to septicemia.

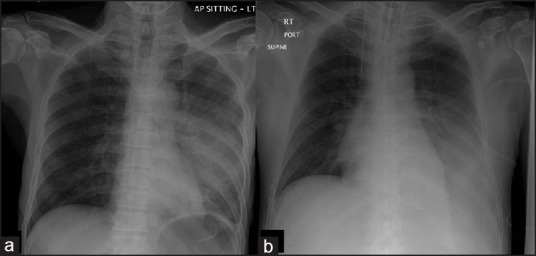

Pulmonary melioidosis is classically an upper lobe infiltrate with or without cavitation. The disease can be categorized into acute and subacute and chronic forms, which can also be subdivided into septicemic and nonsepticemic pneumonia.[11,12,13] Acute pneumonic melioidosis may have a diffuse nodular infiltrate throughout lungs, which may coalesce and cavitate with rapid progression. A discrete but progressive consolidation in one or more lobes is another radiological manifestation [Figure 1]. Acute septicemic pneumonia has a predilection for the upper lobe, whereas lower lobe involvement is more common in nonsepticemic acute melioidosis [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Acute pulmonary melioidosis. Chest X-ray at initial presentation (a) Left upper lobe infiltrate (arrow). Two days later there is interval increase with larger infiltrate. (b) Follow-up X-ray. (c) A week later shows complete opacification of the left hemithorax denoting complete involvement of the left lung.

Figure 2.

(a) Acute septicemic pneumonic melioidosis. Left upper lobe consolidation. (b) Acute nonsepticemic pneumonia in a 50-year-old patient showing left lower opacity.

Subacute and chronic melioidosis may present with mixed nodules or patchy opacities with slower progression in the subacute form.

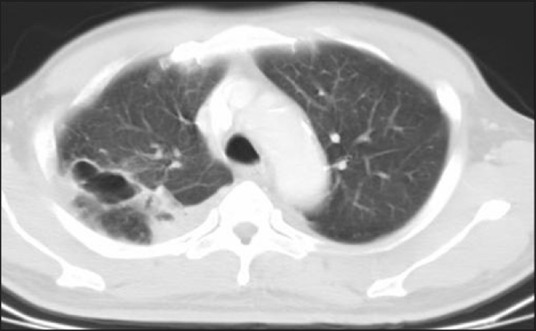

Reactivation of melioidosis varies from latent to a fulminating disease resembling the acute form. Differentiation from tuberculosis may be difficult as both may cause upper lobe infiltrate with cavitations or fibroreticular lesions. Melioidosis cavities are usually thin-walled and rarely contain air/fluid level [Figure 3]. Melioidosis spares the apex of the lung with less fibrosis in the chronic disease. Mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy is rare in melioidosis.[12]

Figure 3.

Pulmonary cavities. The melioidosis cavities have predilection for upper lobes and are usually thin-walled and rarely contain air-fluid levels.

Pleural effusion is uncommon in melioidosis; however, pleural effusion and empyema are more common in lower lobe disease. Rupture of the lung cavities may result in pneumothorax or hydropneumothorax.[9]

Patients with cystic fibrosis may get the colonization of B. pseudomallei in their lungs. Therefore, melioidosis infection should be considered in patients with a traveling history to melioidosis-endemic areas who return sick.[7]

Other uncommon and nonspecific radiological manifestations include intraparenchymal pulmonary pseudoaneurysm and fibrothorax with repeated episodes of pleural effusions and or empyema.[14]

Musculoskeletal and cutaneous melioidosis

Melioidosis infection has variable nonspecific manifestations, in which the skin, subcutaneous tissue, joints, as well as the bones are infected, resulting in septic arthritis, synovitis, osteomyelitis, and soft tissue infections including cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, sinuses or abscess formations.[15] Primary skin infection tends to occur in younger patients with fewer risk factors and more likely to present with the less severe chronic disease with ulcers, pustules, boils, and erythematous lesions. Musculoskeletal involvement is usually part of multisystem melioidosis; the localized form being less common.

VISCERAL MELIOIDOSIS

Spleen

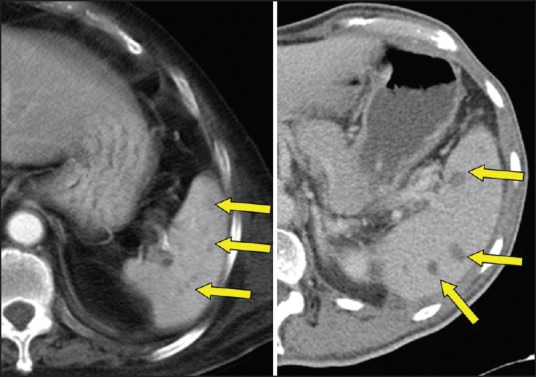

The spleen is the most commonly affected extrapulmonary visceral organ. Splenic lesions are usually multiple, small and discrete, varying from 0.5 cm to 1.5 cm [Figure 4], single or multiple multi-loculated lesions, subcapsular collections with or without perisplenic extension [Figure 5].[2] Single or multiple splenic abscesses were more commonly found in the melioidosis than in the other infections.

Figure 4.

Splenic abscesses. Multiple hypodensities in spleen in two different patients with melioidosis. Note that spleen is mildly to moderately enlarged.

Figure 5.

Splenic abscess with perisplenic extension (blue arrow) along the gastrosplenic ligament (yellow arrow).

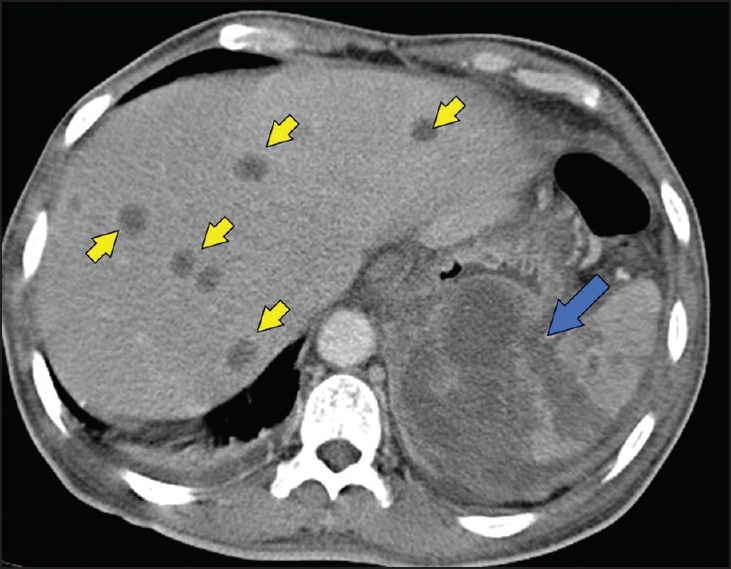

Concurrent spleen and liver abscess are more likely to be associated with melioidosis than with infections caused by other organisms [Figure 6]. B. pseudomallei is the most common causative agent found in patients with spleen and liver abscesses and therefore, empirical antibiotics should be started if the patient is from, or has traveled to an endemic area and presents with multiple splenic abscesses with or without concurrent liver abscess.

Figure 6.

Hepatosplenic melioidosis. Computed tomography scan showing multiple discrete liver abscesses (arrow heads) in the liver and extensive splenic involvement (blue arrow).

Liver

The liver is the second most common visceral organ affected by melioidosis. The radiological appearance varies from multiple discrete lesions [Figure 6], single or multiloculated lesions. Multi-loculated lesions may represent either a cluster of multiple small lesions or coalescence of multiple small abscesses. Liver involvement is usually part of multi-organ involvement rather than a solitary organ involvement.[16]

Kidneys

Involvement of the kidneys varies from multiple ill-defined or well-defined hypo-densities, rim enhancing fluid collections, abscesses, and pyelonephritis. Involvement is more often bilateral and multiple rather than a localized or unilateral disease.

Prostate

One of the unusual manifestations of melioidosis is the involvement of the prostate. Prostatic involvement should be excluded in patients with disseminated disease and lower urinary tract symptoms. Radiological manifestations vary from prostatitis with an enlarged gland and multiple small hypo-densities or abscesses to large frank fluid collections and abscess formation. Prostatic melioidosis has a predilection to the peripheral zone resulting from the bacteremic spread of B. pseudomallei to the prostate in contrast to nonmelioidosis infection. Consequently, prostate specific antigen (PSA) is either normal or mildly increased when compared to higher levels of PSA from other bacterial prostatic infections, and this is probably due to the preferential peripheral zone involvement by melioidosis.[17]

Bowel and peritoneum

Enteritis, colitis, and peritonitis are rare manifestations of melioidosis and are usually part of the disseminated disease.

Central nervous system melioidosis

Central nervous system involvement is usually part of the systemic disease. Neurological melioidosis is a rare condition with nonspecific radiological manifestations including abscess formations, meningoencephalitis, brain stem encephalitis, transverse myelitis, skull osteomyelitis, lymphadenitis, parotitis, and sinonasal disease.[16,17,18,19,20]

CONCLUSION

The radiological manifestations of melioidosis are nonspecific. However, the following findings may suggest the diagnosis of melioidosis in a patient who presents with septicemia or a fever of unknown origin and a history of recent travel to an endemic region.

Upper lobe infiltrate that spares the lung apex.

Upper lobe cavities, which are thin walled with no air fluid levels.

Multiple splenic abscesses.

Concurrent hepatic and splenic abscesses.

Lesions in the periphery of the prostate with normal or mildly raised PSA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gibney KB, Cheng AC, Currie BJ. Cutaneous melioidosis in the tropical top end of Australia: A prospective study and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:603–9. doi: 10.1086/590931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wibulpolprasert B, Dhiensiri T. Visceral organ abscesses in melioidosis: Sonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 1999;27:29–34. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199901)27:1<29::aid-jcu5>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puthucheary SD, Parasakthi N, Lee MK. Septicaemic melioidosis: A review of 50 cases from Malaysia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:683–5. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90191-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitemore A, Krishnaswami CS. An account of the discovery of hitherto undescribed infective disease occurring among the population of Rangoon. Ind Med Gaz. 1912;47:262–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leelarasamee A, Bovornkitti S. Melioidosis: Review and update. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:413–25. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Currie BJ. Melioidosis: An important cause of pneumonia in residents of and travellers returned from endemic regions. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:542–50. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00006203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brett PJ, Woods DE. Pathogenesis of and immunity to melioidosis. Acta Trop. 2000;74:201–10. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(99)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raja NS. Cases of melioidosis in a university teaching hospital in Malaysia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008;41:174–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muttarak M, Peh WC, Euathrongchit J, Lin SE, Tan AG, Lerttumnongtum P, et al. Spectrum of imaging findings in melioidosis. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:514–21. doi: 10.1259/bjr/15785231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chlebicki MP, Tan BH. Six cases of suppurative lymphadenitis caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:798–801. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ip M, Osterberg LG, Chau PY, Raffin TA. Pulmonary melioidosis. Chest. 1995;108:1420–4. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.5.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singcharoen T. CT findings in melioidosis. Australas Radiol. 1989;33:376–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1989.tb03316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puthucheary SD. Melioidosis in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2009;64:266–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anunnatsiri S, Chetchotisakd P, Kularbkaew C. Mycotic aneurysm in Northeast Thailand: The importance of Burkholderia pseudomallei as a causative pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1436–9. doi: 10.1086/592975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popoff I, Nagamori J, Currie B. Melioidotic osteomyelitis in northern Australia. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997;67:692–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1997.tb07111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ben RJ, Tsai YY, Chen JC, Feng NH. Non-septicemic Burkholderia pseudomallei liver abscess in a young man. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2004;37:254–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morse LP, Moller CC, Harvey E, Ward L, Cheng AC, Carson PJ, et al. Prostatic abscess due to Burkholderia pseudomallei: 81 cases from a 19-year prospective melioidosis study. J Urol. 2009;182:542–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currie BJ, Fisher DA, Howard DM, Burrow JN. Neurological melioidosis. Acta Trop. 2000;74:145–51. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(99)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartley PP, Pender MP, Woods ML, 2nd, Walker D, Douglas JA, Allworth AM, et al. Spinal cord disease due to melioidosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1999;93:175–6. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(99)90299-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim RS, Flatman S, Dahm MC. Sinonasal melioidosis in a returned traveller presenting with nasal cellulitis and sinusitis. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2013;2013:920352. doi: 10.1155/2013/920352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]