Abstract

Purpose

This study examined whether the neuroprotective drug, 3-n-butylphthalide (NBP), which is used to treat ischemic stroke, prevents mitochondrial dysfunction.

Materials and methods

PC12 neuronal cells were pretreated for 24 hours with NBP (10 μmol/L), then exposed to oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) for 8 hours as an in vitro model of ischemic stroke. Indices of anti-oxidative response, mitochondrial function and mitochondrial dynamics were evaluated.

Results

OGD suppressed cell viability, induced apoptosis and increased caspase-3 activity. NBP significantly reversed these effects. NBP prevented oxidative damage by increasing the activity of superoxide dismutase and lowering levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) and reactive oxygen species (ROS). At the same time, it increased expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and AMPK. NBP attenuated mitochondrial dysfunction by enhancing mitochondrial membrane potential and increasing the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes I–IV and ATPase. NBP altered the balance of proteins regulating mitochondrial fusion and division.

Conclusion

NBP exerts neuroprotective actions by enhancing anti-oxidation and attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction. Our findings provide insight into how NBP may exert neuroprotective effects in ischemic stroke and raise the possibility that it may function similarly against other neurodegenerative diseases involving mitochondrial dysfunction.

Keywords: ischemic stroke, mitochondrial dysfunction, mitochondrial dynamics, neuroprotective

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a major risk factor for vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and it is associated with high neurological disability and mortality.1–3 Within a few minutes, the cascade of reactions caused by ischemic stroke can lead to irreversible functional impairment of nerve tissue in the ischemic core. Ischemic stroke is thought to occur when cerebral artery stenosis and reduction or interruption of regional cerebral blood flow decrease the supply of oxygen and energy to brain tissue, triggering secondary vascular endothelial damage and autonomic nervous dysfunction.4,5 Cellular and animal models and postmortem studies indicate that ischemic stroke involves oxidative stress, apoptosis, calcium overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammatory and immune responses, as well as changes in microRNA levels.6–9 Mitochondrial dysfunction appears to contribute to ischemic stroke by increasing oxidative stress, perturbing calcium homeostasis and inducing neuronal apoptosis.10

Oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD), one of the most important pathogenic mechanisms in cerebral infarction,11 is widely used in vitro as a model of ischemic stroke. OGD induces oxidative stress and formation of ROS, which damage cerebral neurons. Radicals can induce lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA damage.

Drug therapies to treat ischemic stroke are unsatisfactory. The only drug so far licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat ischemic stroke is intravenous serine protease tissue-type plasminogen activator.12 Therefore, new drugs that are safe and effective against ischemic stroke are vitally important.

One promising compound is 3-n-butylphthalide (NBP), which was approved for ischemic stroke by the State Food and Drug Administration in China in 2002. In clinical studies, NBP inhibited platelet aggregation, reduced ischemia-induced oxidative damage, regulated energy metabolism, improved microcirculation and reduced brain infarct size.13–15 Whether NBP also acts to preserve mitochondrial function is unclear.

Here, we examined whether NBP may exert its neuroprotective effects in part by protecting against mitochondrial dysfunction. As an in vitro model of ischemic stroke, we exposed PC12 neuronal cells to OGD with or without NBP pretreatment; then, we measured anti-oxidation and mitochondrial function. Our findings may help clarify the mechanism of NBP against ischemic stroke and potentially other neurodegenerative diseases involving mitochondrial dysfunction.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

NBP was obtained from Shijiazhuang Pharma Group NBP Pharmaceutical with a purity of >99%. The drug was dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). The reagents MTT and JC-1 probe were purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China). Rhodamine-123, 2′,7′-dichlorofluoresceine diacetate (DCF-DA), Mito Tracker Green FM probe and the Caspase-3 Activity Assay kit were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. ELISA kits to assay superoxide dismutase (SOD), MDA, mitochondrial respiratory chain enzymes activities I–IV and mitochondrial ATPase were obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, Jiangsu, People’s Republic of China). Primary antibodies against Mfn1, Mfn2, OPA1, Drp1, Fis1, Nrf2, HO-1 and AMPK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Primary antibody against GAPDH was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Cell culture and treatments

PC12 neuronal cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in DMEM (Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS. Cultures were divided into four groups: the control group was PC12 cells cultured in DMEM and supplemented with 10% FBS; the OGD group was subjected to 8 hours of OGD; the NBP group, to NBP treatment for 24 hours; and the NBP+OGD group, to NBP pretreatment for 24 hours, followed by OGD for 8 hours. For OGD, cultures were washed three times with glucose-free DMEM and incubated in this medium. Cultures were sealed in an airtight chamber that had a volume of ~12 L, which was equilibrated for 10 minutes with 95% N2/5% CO2 in continuous flux. Finally, the chamber was sealed and placed in an incubator at 37°C for 8 h.16 Control cultures were not subjected to OGD and were instead cultured in normal oxygenated DMEM containing glucose. Each experiment was performed at least six times.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, PC12 cells (5×103 per well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and pretreated with different concentrations of NBP (0.01, 0.1, 10 or 100 μM) for 24 hours, then exposed for 24 hours to OGD. At the end of the experiment, 20 μL MTT (5 mg/mL) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 4 hours. Culture supernatants were discarded, MTT crystals were dissolved in DMSO and absorbance at 570 nm was detected using a microplate reader (iMark; Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative cell viability (%) was defined as the absorbance of the treated samples relative to that of the untreated control (defined as 100%). All experiments were performed at least three times.

TUNEL assay of apoptosis

DNA fragmentation was detected in situ using the TUNEL assay (KeyGen Biotech, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China). Briefly, samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, and then rinsed with PBS for 5 minutes and incubated for 2 minutes on ice in permeabilization solution (1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate). The TUNEL reaction mixture was added, and the samples were incubated in the dark for 1 hour at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2). Finally, samples were stained with 1 μg/mL of DAPI for 15 minutes. Samples were rinsed with PBS, then analyzed under a fluorescence microscope using an excitation wavelength in the range 450–500 nm and detection in the range 515–565 nm. The extent of apoptosis was expressed as the percentage of all DAPI-stained cells that were TUNEL-positive within the same area. For each treatment, this percentage was determined in five randomly selected fields and averaged.

Caspase-3 activity assay

Caspase-3 activity was detected using a commercial assay kit. Briefly, PC12 cells were harvested and homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid). Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 minutes; then, duplicate sets of supernatants were mixed with the caspase-3 substrate Ac-DEVD-pNA to a final concentration of 100 μM. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours, and absorbance at 450 nm was measured, reflecting cleavage of the colorimetric substrate.

Ultrastructural and morphological assessment of mitochondria

Cells treated in different ways were harvested, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and analyzed by transmission electron microscopy to reveal cellular and mitochondrial ultrastructure. Cells were also diluted with 25 nmol Mito Tracker Green fluorescent probe (1:1,000), then incubated at 37°C for 45 minutes. Cultures were washed three times with sterile PBS, fixed with paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS and seasoned. Cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope to reveal mitochondrial morphology.

Mitochondrial protein assay

Mitochondria were prepared as described with some modifications.17,18 All solution and equipment were precooled to 4°C and kept on ice throughout the procedure of mitochondrial isolation. Cells were treated in different ways, washed twice with ice-cold PBS and centrifuged at 750× g for 5 minutes at 4°C. The volume of pelleted cells was determined and five volumes of buffer A (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 250 mM sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) were added. Cells were incubated on ice for 2 minutes, then homogenized with a syringe 20–30 times, and breakage of >90% cells was confirmed. Homogenates were centrifuged twice at 750× g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were then spun at 10,000× g for 15 minutes at 4°C to obtain mitochondrial pellets, which were resuspended in buffer A. Concentration of total mitochondrial protein was estimated using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay kit (Beyotime).

SOD and MDA assays

Intracellular SOD activities and MDA levels were analyzed using commercial kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng Biotech, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China).

Intracellular ROS assay

Cultures were digested with trypsin, and digestion was terminated by addition of serum-containing culture medium. The resulting cell suspensions were centrifuged at 1,000× g for 5–10 minutes, washed 1–2 times with PBS and the cells were collected by centrifugation. A single-cell suspension was prepared and DCFH-DA was added to a final concentration of 10 μM. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C, cells were collected by centrifugation and ROS levels were determined using an upflow BD-FACSVerse cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The excitation wavelength was 488 nm, and the emission wavelength was 525 nm. Data were analyzed using CELL Quest software.

Mitochondrial membrane potential determination

Cultures were treated in different ways, the medium was aspirated, cells were washed with PBS, then incubated with 1 mL of cell culture solution and 1 mL of working solution of JC-1 stain. Cultures were then observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope.

Assays of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes (MRCC) I–IV and ATPase

Activities of MRCC I–IV were assayed using the commercial Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complex Activity Assay Kits and were quantified using an UV-9100 spectrophotometer. All assays were performed at 30°C, except for the assay of complex IV, which was performed at 25°C. Mitochondria were freeze-thawed for several rounds in hypotonic media containing 25 mM potassium phosphate and 5 mM MgCl2. Activity of MRCC I, expressed as nmol oxidized NADH/min/mg protein, was measured with or without ROT by monitoring the oxidation of 100 μM NADH at 340 nm. The activity of MRCC II, expressed as nmol reduced DCIP/min/mg protein, was assayed by adding 50 μM decylubiquinone and monitoring the reduction of 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol at 600 nm. Activity of MRCC III, expressed as nmol reduced cytochrome c/min/mg protein, was measured by tracking the reduction of cytochrome c at 550 nm with or without antimycin A, a specific inhibitor of ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase. Activity of MRCC IV, expressed as nmol oxidized cytochrome c/min/mg protein, was determined by monitoring the oxidation of cytochrome c at 550 nm.18 All measurements were performed in triplicate. The activity of ATPase was determined using commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Biotech) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blotting analysis

Cultures were harvested, washed with PBS and lysed with cell lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000× g for 15 minutes to remove insoluble material. Supernates were collected, and mitochondrial fractions were separated using the Cell Mitochondrial Isolation Kit (Beyotime) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Proteins were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit. Equal amounts of protein lysate (30 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE on 10%–12% polyacrylamide gels and electrotransferred to polyvinylidenedifluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Membranes were blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 5% skimmed milk at room temperature for 30 minutes, then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against Nrf2, HO-1, AMPK, Mfn1, Mfn2, OPA1, Drp1, Fis1 or GAPDH. Membranes were washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at room temperature for 1 hour. Protein bands were detected using chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA) with P<0.05 defined as significant. Data are presented as the mean±SD of at least three independent experiments. The significance of inter-group differences was assessed using one-way ANOVA.

Results

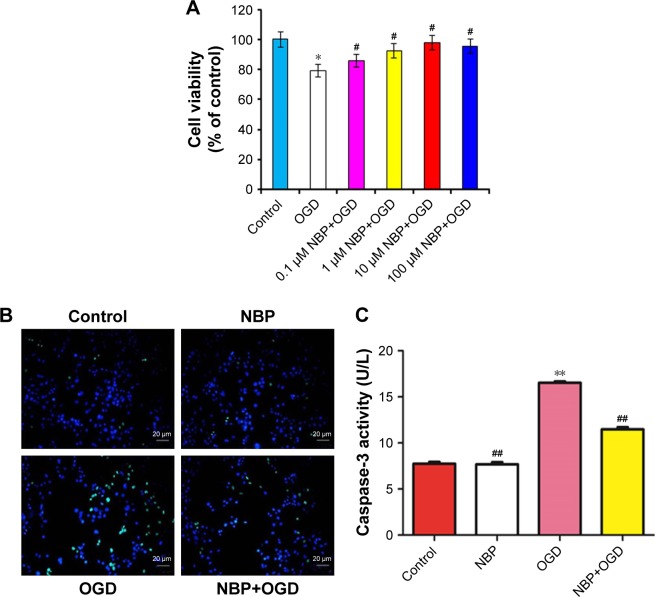

Effect of NBP on cell viability and apoptosis after OGD

PC12 cells treated with OGD for 24 hours showed 79.3%±0.004% survival relative to the control group. Cells first treated for 24 hours with NBP at 0.1, 1, 10 or 100 μmol and then exposed to OGD for 8 hours showed respective survival rates of 85.7.2%±0.010%, 92.6%±0.010%, 98.0%±0.007% and 95.6%±0.010%. Pretreatment with NBP at 0.1–100 μM led to significantly less OGD-induced cell death than without pretreatment (Figure 1A, P<0.05). Protection by 100 μM NBP was not significantly different from protection by 10 μM, suggesting that 10 μM NBP was the maximal protective dose under our experimental conditions. Therefore, this concentration was chosen for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Effect of NBP on cell viability and apoptosis following OGD.

Notes: PC12 cells were pretreated with different concentrations of NBP, then exposed to OGD. (A) Viability was measured in the MTT assay. (B) Apoptosis was detected using TUNEL staining. (C) Caspase-3 activity was measured using a commercial kit. Bars show mean±SD of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs control, #P<0.05 vs OGD-treated. **P<0.01 vs control, ##P<0.01 vs OGD-treated.

Abbreviations: NBP, 3-n-butylphthalide; OGD, oxygen and glucose deprivation.

Cells treated in these ways were examined in a TUNEL assay to determine whether NBP pretreatment can reduce OGD-induced apoptosis. OGD led to greater numbers of apoptotic cells than in control and NBP groups (Figure 1B). The smaller numbers of apoptotic cells following NBP pretreatment suggests that the drug reduces apoptosis. We further found that OGD significantly increased caspase-3 activity (Figure 1C, P<0.01), and this activity was significantly lower when cells were pretreated with NBP (Figure 1C, P<0.01). This suggests that NBP reduces neuronal apoptosis after OGD by mitigating mitochondrial damage.

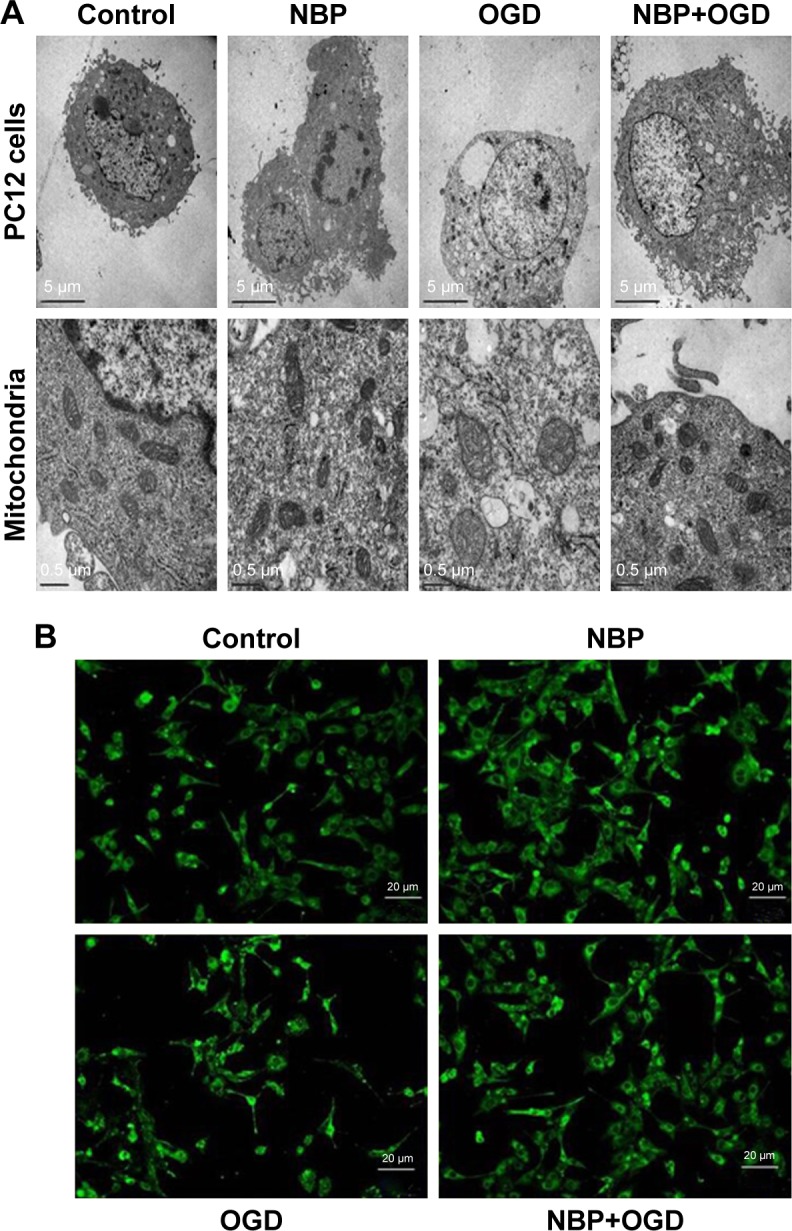

NBP helps maintain normal cellular and mitochondrial morphology after OGD

By transmission electron microscopy, cells in the control and NBP groups showed homogeneous density, clear edges of the cell membrane, abundant microvilli, uniform cell chromatin and overall normal morphology. In both conditions, the mitochondrial cristae were clear and dense. OGD caused mitochondria to shorten and mitochondrial cristae to appear coarse and ruptured. This damage was visibly less if cells were pretreated with NBP (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

The drug NBP protects PC12 cells and mitochondria from damage due to OGD.

Notes: (A) Ultrastructure of PC12 cells and mitochondria by transmission electron microscopy. (B) Morphology of mitochondria by fluorescence microscopy after staining with Mito Tracker Green FM.

Abbreviations: NBP, 3-n-butylphthalide; OGD, oxygen and glucose deprivation.

As a complement to transmission electron microscopy, mitochondria in treated cells were also examined with fluorescence microscopy after labeling the organelles with Mito Tracker Green FM. In control and NBP cells, mitochondria showed uniform, normal morphology and length (Figure 2B). OGD reduced the number of long tubular mitochondria, and most mitochondria showed a point-like change, with perinuclear aggregation. OGD also caused cells to become round, the cell body to enlarge and synapses to shorten or even disappear. These effects were visibly reduced when cells were pretreated with NBP (Figure 2B).

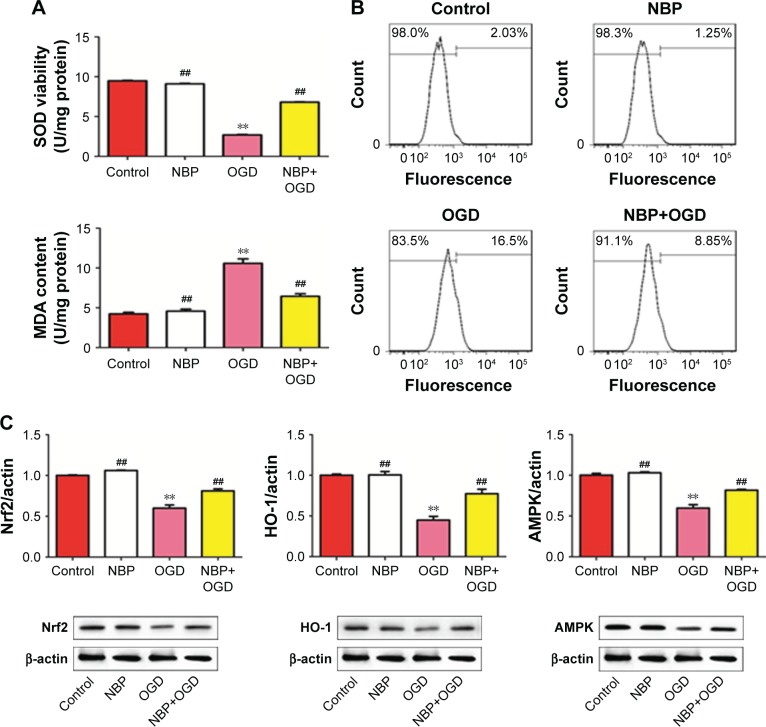

NBP protects against OGD-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells

Because accumulation of oxidative stress products is an important cause of mitochondrial damage, we asked whether OGD leads to oxidative stress and whether NBP can protect against it. While the control and NBP groups did not differ significantly in SOD activity or MDA level, OGD significantly reduced SOD activity and increased MDA level (Figure 3A, P<0.01). These effects were reversed to a significant extent by NBP pretreatment (Figure 3A, P<0.01). Similarly, ROS production increased by 16.5% after OGD, which was reduced to 8.85% with NBP pretreatment (Figure 3B). These results suggest that NBP can promote anti-oxidative effects, reducing the extent of lipid peroxidation and free radical damage to mitochondria.

Figure 3.

The drug NBP protects PC12 cells against oxidative stress induced by OGD.

Notes: (A) Effect of NBP on SOD activity and MDA levels. (B) Effect of NBP on production of ROS. (C) Effect of NBP on expression of anti-oxidant proteins. **P<0.01 vs control, ##P<0.01 vs OGD-treated.

Abbreviations: MDA, malondialdehyde; NBP, 3-n-butylphthalide; OGD, oxygen and glucose deprivation; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Consistent with an anti-oxidative effect of NBP, we found that while OGD significantly downregulated Nrf2, HO-1 and AMPK (Figure 3C, P<0.01), NBP pretreatment significantly upregulated these genes (Figure 3C, P<0.01). Nevertheless, the expression of these proteins after NBP pretreatment was still lower than in control cells.

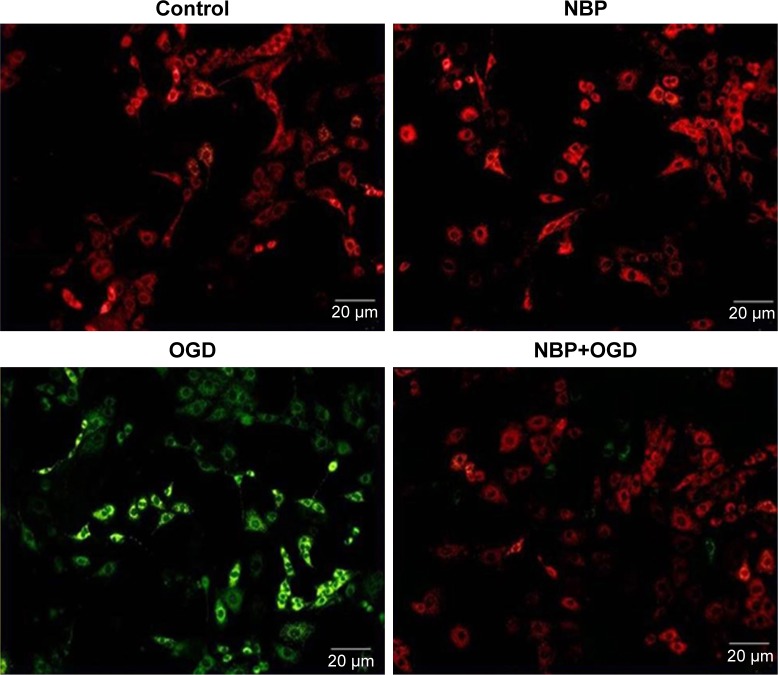

NBP helps preserve mitochondrial membrane potential after OGD

Another indicator of mitochondrial function is the mitochondrial membrane potential, so we examined this potential following OGD with or without NBP pretreatment. OGD reduced this potential, which was observed as an increase in green fluorescence. The potential was significantly higher when cells were pretreated with NBP (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of NBP on mitochondrial membrane potential in PC12 cells after OGD.

Abbreviations: NBP, 3-n-butylphthalide; OGD, oxygen and glucose deprivation.

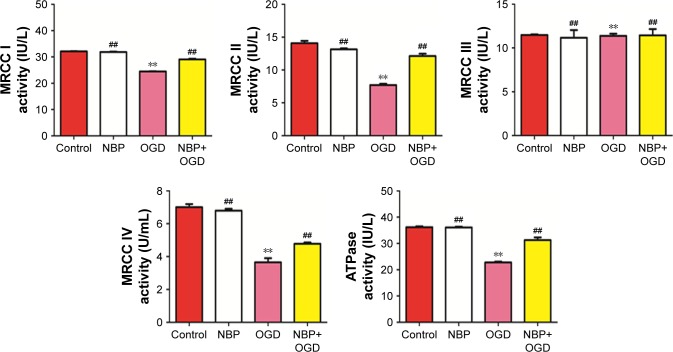

NBP boosts activity of MRCC I–IV and ATPase after OGD

To gain further insight into the effects of NBP on mitochondrial function, we measured effects of OGD with or without drug pretreatment on the activity of MRCC I–IV and ATPase. OGD significantly reduced the activity of MRCC I, II and IV, and these effects were significantly reversed by NBP pretreatment (Figure 5A–D, ##P<0.01) (MRCC III was not significantly affected by OGD or NBP). Similarly, OGD significantly reduced ATPase activity, and NBP pretreatment significantly reversed this effect (Figure 5E, P<0.01). These results suggest that NBP increases energy synthesis by mitochondria, thereby helping to reduce mitochondrial damage induced by OGD.

Figure 5.

Effect of NBP on the activity of MRCC I–IV and ATPase in PC12 cells after OGD.

Note: **P<0.01 vs control, ##P<0.01 vs OGD-treated.

Abbreviations: MRCC, mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes; NBP, 3-n-butylphthalide; OGD, oxygen and glucose deprivation.

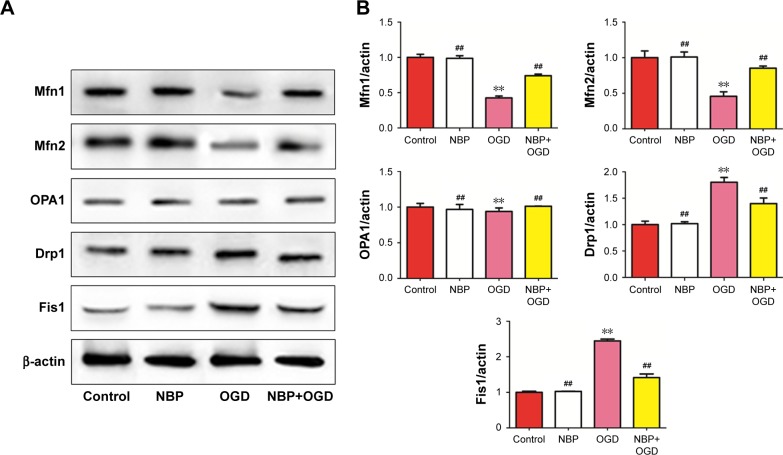

NBP may regulate mitochondrial fusion and division to preserve mitochondrial function after OGD

Mitochondria repeatedly undergo fusion and division, and a dynamic balance between the two processes is regulated by fusion-related proteins (Mfn1, Mfn2 and OPA1) and by division-related proteins (Drp1 and Fis1). OGD significantly downregulated Mfn1 and Mfn2 while upregulating Drp1 and Fis1 (Figure 6, P<0.01). These effects were significantly reversed by NBP pretreatment (Figure 6, P<0.01). (OPA1 expression was not significantly affected by OGD or NBP). These results suggest that NBP may protect PC12 nerve cells from OGD-induced damage in part by regulating the dynamic balance between mitochondrial fusion and division.

Figure 6.

Effect of NBP on mitochondrial dynamics in PC12 cells after OGD.

Notes: (A) Western blotting was used to determine relative expression levels of Mfn1, Mfn2, OPA1, Drp1 and Fis1. (B) The bars represent Mfn1, Mfn2, OPA1, Drp1 and Fis1 protein/β-ACTIN levels in NBP, OGD, NBP+OGD group compared to control. **P<0.01 vs control, ##P<0.01 vs OGD-treated.

Abbreviations: NBP, 3-n-butylphthalide; OGD, oxygen and glucose deprivation.

Discussion

Ischemic stroke threatens the lives of tens of millions of people around the world. Long-term cerebral ischemia can lead to a decline in cognitive function, which is associated with vascular dementia. Cognitive dysfunction after cerebral ischemia appears to involve free radical damage, apoptosis and mitochondrial damage.17 The present study, conducted in an in vitro model of ischemic stroke induced by OGD, suggests that all these effects can be substantially mitigated by NBP. These findings may help to explain how the drug can restore microcirculation in cerebral ischemic area and improve brain energy metabolism after acute ischemic stroke.14

In our in vitro model involving PC12 neuronal cells exposed to OGD,19 this exposure induced increased activity of caspase-3, while NBP pretreatment reversed this. Caspase-3 is a major cell death effector protease,20 and its activation is associated with apoptotic cell death phenotypes.21 In our study, this anti-apoptotic effect was associated with the following: preservation of cellular and mitochondrial morphology, as observed using two microscopy techniques; reversal in OGD-induced inhibition of SOD; production of MDA and ROS and downregulation of the anti-oxidant protein Nrf2 as well as its target proteins HO-1 and AMPK. SOD is an important anti-oxidant enzyme that acts as a first line of defense,22 and increased MDA indicates oxidative damage of membranes. Hence, increasing SOD activity and decreasing levels of MDA are beneficial for preventing oxidative damage.23,24 Nrf2 defends against oxidative stress by regulating expression of various anti-oxidant proteins.25,26 Multiple studies have shown that OGD-induced neuronal oxidative damage can be significantly attenuated by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway.27–29 AMPK regulates cellular energy metabolism, and its activation helps bring metabolic processes into balance. AMPK activates the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling axis, suggesting tight cooperation between signaling pathways controlling cellular redox and energy homeostasis.30,31

Previous work suggested that myocardial ischemia can increase ROS production and impair the function of the mitochondrial electron transport chain.32 Mitochondria are the main site of ROS production in cells and are susceptible to oxidative damage. Mitochondrial membrane potential is a sensitive indicator of mitochondrial function. Moderate cell damage can reduce this potential and enlarge the pores of the mitochondrial outer membrane, leading to the release of cytochrome c into the cytoplasm, ultimately triggering apoptosis.33 In our study, OGD significantly reduced mitochondrial membrane potential, and this effect was significantly reversed by NBP pretreatment. Similarly, OGD significantly decreased the activity of MRCC I, II and IV as well as the ATPase, and these effects were significantly reversed by NBP pretreatment. Our results suggest that NBP may protect against OGD-induced mitochondrial damage by stabilizing mitochondrial membrane potential and boosting the activity of the electron transport chain, thereby increasing mitochondrial energy synthesis.

Aberrant mitochondrial dynamics are also important causes of mitochondrial dysfunction.32 Because mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles, they repeatedly divide, fuse and form networks in cells. Defects in mitochondrial dynamics are associated with poor bioenergetic supply and pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases.34–36 Mitochondrial division and fusion are coordinated by several proteins. The mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 control fusion of the mitochondrial outer membrane, and OPA1 controls fusion of the mitochondrial inner membrane. Drp1 and Fis1 regulate mitochondrial division. Abnormal Drp1 activation triggers changes in mitochondrial morphology and impairs mitochondrial function. This increases ROS production and decreases ATP production, ultimately leading to cell death.37 OGD destroys the physiological balance between mitochondrial fusion and division: in our experiments, it significantly downregulated Mfn1 and Mfn2, and it significantly upregulated Drp1 and Fis1. These effects were significantly reversed with NBP pretreatment. Thus, the neuroprotective effects of NBP may involve, at least in part, the restoration of the dynamic balance between mitochondrial fusion and division.

Conclusion

Our study in an in vitro model of ischemic stroke provides evidence that NBP exerts neuroprotective effects by enhancing anti-oxidation and attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction. Our results may help clarify why the drug is effective in ischemic stroke and why it may be useful against other neurodegenerative diseases that involve mitochondrial dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Key Research and Development Project of Guangxi (Guike AB17195002), Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (2017GXNSFAA198249), the Scientific Research Fund of the Population and Family Planning Commission of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (S2017009), Department of Education of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (2017JGA159) and the Talents Highland of Emergency and Medical Rescue of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Khoshnam SE, Sarkaki A, Rashno M, Farbood Y. Memory deficits and hippocampal inflammation in cerebral hypoperfusion and reperfusion in male rats: neuroprotective role of vanillic acid. Life Sci. 2018;211:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen TV, Hayes M, Zbesko JC, et al. Alzheimer’s associated amyloid and tau deposition co-localizes with a homeostatic myelin repair pathway in two mouse models of post-stroke mixed dementia. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2018;6(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0603-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subic A, Zupanic E, von Euler M, et al. Stroke as a cause of death in death certificates of patients with dementia: a cohort study from the Swedish Dementia Registry. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2018:1322–1330. doi: 10.2174/1567205015666181002134155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong P, Wu D, Ye X, et al. Secondary prevention of major cerebrovascular events with seven different statins: a multi-treatment meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:2517–2526. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S135785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou D, Liu C, Zhang Q, et al. Association between polymorphisms in microRNAs and ischemic stroke in an Asian population: evidence based on 6,083 cases and 7,248 controls. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1709–1726. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S174000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fluri F, Schuhmann MK, Kleinschnitz C. Animal models of ischemic stroke and their application in clinical research. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:3445–3454. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S56071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harukuni I, Bhardwaj A. Mechanisms of brain injury after global cerebral ischemia. Neurol Clin. 2006;24(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuttolomondo A, Pecoraro R, Pinto A. Studies of selective TNF inhibitors in the treatment of brain injury from stroke and trauma: a review of the evidence to date. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:2221–2238. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S67655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijayan M, Reddy PH. Stroke, vascular dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease: molecular links. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(2):427–443. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang DB, Kinoshita C, Kinoshita Y, et al. Neuronal susceptibility to beta-amyloid toxicity and ischemic injury involves histone deacety-lase-2 regulation of endophilin-B1. Brain Pathol. 2018 Jul 20; doi: 10.1111/bpa.12647. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi NY, Kim JY, Hwang M, et al. Atorvastatin rejuvenates neural stem cells injured by oxygen-glucose deprivation and induces neuronal differentiation through activating the PI3K/Akt and ERK pathways. Mol Neurobiol. 2018 Aug 3; doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1267-6. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan Z, Xu X, Xu W, et al. Discovery of 3-n-butyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-1-one as a potential anti-ischemic stroke agent. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:3377–3391. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S84731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li L, Zhang B, Tao Y, et al. DL-3-n-butylphthalide protects endothelial cells against oxidative/nitrosative stress, mitochondrial damage and subsequent cell death after oxygen glucose deprivation in vitro. Brain Res. 2009;1290:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu CL, Liao SJ, Zeng JS, et al. DL-3n-butylphthalide prevents stroke via improvement of cerebral microvessels in RHRSP. J Neurol Sci. 2007;260(1–2):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng Y, Zeng X, Feng Y, Wang X. Antiplatelet and antithrombotic activity of L-3-n-butylphthalide in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;43(6):876–881. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200406000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang T, Wang H, Li Q, Huang J, Sun X. Modulating autophagy affects neuroamyloidogenesis in an in vitro ischemic stroke model. Neuroscience. 2014;263:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brustovetsky N, Brustovetsky T, Jemmerson R, Dubinsky JM. Calcium-induced cytochrome c release from CNS mitochondria is associated with the permeability transition and rupture of the outer membrane. J Neurochem. 2002;80(2):207–218. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao F, Li Y, Luo L, et al. Role of mitochondrial electron transport chain dysfunction in Cr(VI)-induced cytotoxicity in L-02 hepatocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;33(4):1013–1025. doi: 10.1159/000358672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao T, Fu Y, Sun H, Liu X. Ligustrazine suppresses neuron apoptosis via the Bax/Bcl-2 and caspase-3 pathway in PC12 cells and in rats with vascular dementia. IUBMB Life. 2018;70(1):60–70. doi: 10.1002/iub.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le DA, Wu Y, Huang Z, et al. Caspase activation and neuroprotection in caspase-3-deficient mice after in vivo cerebral ischemia and in vitro oxygen glucose deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(23):15188–15193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232473399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newcomb-Fernandez JK, Zhao X, Pike BR, et al. Concurrent assessment of calpain and caspase-3 activation after oxygen-glucose deprivation in primary septo-hippocampal cultures. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21(11):1281–1294. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rizvi SI, Maurya PK. Alterations in antioxidant enzymes during aging in humans. Mol Biotechnol. 2007;37(1):58–61. doi: 10.1007/s12033-007-0048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen N-Y, Liu C-W, Lin W, et al. Extract of fructus cannabis ameliorates learning and memory impairment induced by D-galactose in an aging rats model. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017(11):1–13. doi: 10.1155/2017/4757520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian Y, Zou B, Yang L, et al. High molecular weight persimmon tannin ameliorates cognition deficits and attenuates oxidative damage in senescent mice induced by D-galactose. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(8):1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okada K, Shoda J, Taguchi K, et al. Nrf2 counteracts cholestatic liver injury via stimulation of hepatic defense systems. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;389(3):431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.08.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu W, Hellerbrand C, Köhler UA, et al. The Nrf2 transcription factor protects from toxin-induced liver injury and fibrosis. Lab Invest. 2008;88(10):1068–1078. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin R, Cai J, Kostuk EW, Rosenwasser R, Iacovitti L. Fumarate modulates the immune/inflammatory response and rescues nerve cells and neurological function after stroke in rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):269. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0733-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lv C, Maharjan S, Wang Q, et al. α-Lipoic acid promotes neurological recovery after ischemic stroke by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway to attenuate oxidative damage. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;43(3):1273–1287. doi: 10.1159/000481840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y, Kabba JA, Ruan W, et al. The PGC-1α activator ZLN005 ameliorates ischemia-induced neuronal injury in vitro and in vivo. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2018;38(4):929–939. doi: 10.1007/s10571-017-0567-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang H, Feng A, Lin S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-21 prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy via AMPK-mediated antioxidation and lipid-lowering effects in the heart. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(2):227. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0307-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimmermann K, Baldinger J, Mayerhofer B, Atanasov AG, Dirsch VM, Heiss EH. Activated AMPK boosts the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling axis-A role for the unfolded protein response. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;88(PtB):417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paradies G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM, Petrosillo G. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and cardiolipin alterations in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Implications for pharmacological cardioprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018:H1341–H1352. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00028.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu W, Zhou X, Liu P, Fei W, Li L, Yun H. Isoflurane reduces hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis and mitochondrial permeability transition in rat primary cultured cardiocytes. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;14:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-14-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerveny KL, Tamura Y, Zhang Z, Jensen RE, Sesaki H. Regulation of mitochondrial fusion and division. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(11):563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perfettini JL, Roumier T, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in the control of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15(4):179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westermann B. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(12):872–884. doi: 10.1038/nrm3013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marsboom G, Toth PT, Ryan JJ, et al. Dynamin-related protein 1-mediated mitochondrial mitotic fission permits hyperproliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and offers a novel therapeutic target in pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2012;110(11):1484–1497. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.263848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]