Abstract

Early treatment is associated with improved outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), suggesting that a ‘window of opportunity’, in which the disease is most susceptible to disease-modifying treatment, exists. Autoantibodies and markers of systemic inflammation can be present (long) before clinical arthritis and maturation of the immune response seems to coincide with RA-development. The symptomatic pre-arthritis phase is now hypothesized to comprise a part of that window of opportunity. Consequently, disease modulation in this phase might prevent the occurrence of clinically-apparent arthritis, which would otherwise result in a persistent disease course. Several ongoing proof-of-concept trials are now testing this hypothesis. In this Review, the importance of adequate risk prediction for the correct design, execution and interpretation of results of these prevention trials is highlighted, as well as considerations when translating these findings into clinical practice. The patients’ perspectives are discussed, and the accuracy with which RA-development can be predicted in patients presenting with arthralgia is evaluated. Currently, the best starting position for preventive studies is proposed to be the inclusion of patients with an increased risk of RA, such as those identified as fulfilling the EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to RA.

Introduction

Early initiation of effective DMARDs and the treat-to-target approach are the cornerstones of current treatment strategies for rheumatoid arthritis (RA)1,2. Underlying the relevance of early treatment initiation is the concept of a ‘window of opportunity’, which presumes that a confined period exists in which the disease is most susceptible to the disease-modifying effects of treatment3,4. Although the exact timeline of disease progression has yet to be determined, an important proportion of this window could be situated before arthritis becomes clinically evident.

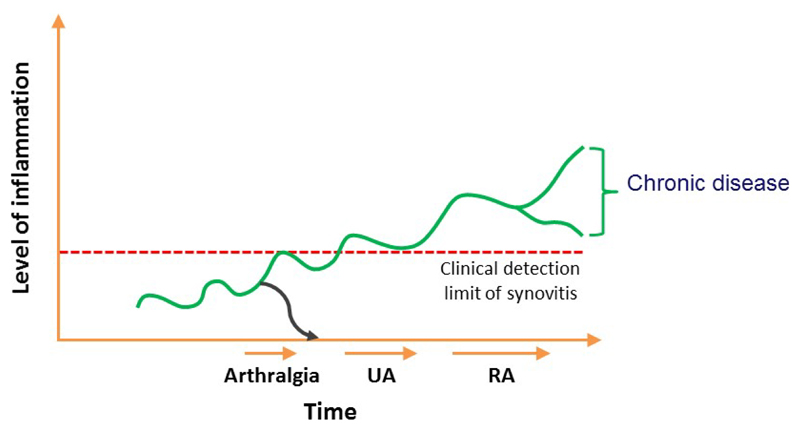

Current therapies for treating RA are effective in suppressing inflammation, but their ability to modify the persistent course of the disease is limited5. Retrospective nested case-control studies have revealed that RA-related autoantibodies and markers of systemic or local subclinical inflammation can be present years or months before the patient diagnosis6–12, demonstrating that the disease process is evolving long before the disease becomes clinically detectable. On the basis of current understandings of RA etiopathogenesis, the EULAR study group for risk factors for RA has defined several phases of RA development. These phases comprise of: genetic and environmental risk factors for RA, autoimmunity associated with RA, symptoms such as joint pain but without clinical arthritis (arthralgia) and clinical arthritis (which can be either unclassified arthritis or RA)30. Such observations have encouraged a call for ‘preventive trials’: trials that assess treatment initiation in pre-arthritis phases with the ultimate aim of preventing the onset of RA (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic view of rheumatoid arthritis development over time in relation to level of inflammation; it is presumed that disease modifying treatment initiated in the phase of arthralgia may prevent progression to persistent arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (as indicated with the blue line).

This challenge raises questions concerning how to accurately identify individuals in the pre-arthritis phases, how to avoid overtreatment and how to manage patients that are presumed to be at risk of developing RA. In this Review, we discuss what is known on the identification of patients at risk of developing RA in different pre-arthritis phases, particularly patients with arthralgia, and the methodological concerns of designing clinical trials of such patients.

Research into preventative treatment

Efficacy of early treatment

At present, all evidence supporting early treatment initiation come from studies of patients with clinically-manifest arthritis2,13. Very few trials on treatment initiated in the pre-arthritis phases have been published until now.

Results from studies of experimental animal models of arthritis suggest that providing treatment before arthritis is clinically evident is efficacious. In 2017, a systematic literature review14, which included a meta-analysis of 16 such animal model studies, demonstrated that starting immunosuppressive treatment in the induction phase of experimental arthritis (that is, before the development of clinical arthritis and the autoantibody response), has beneficial effects on arthritis severity compared with no treatment. Data was most compelling for methotrexate and abatacept (an inhibitor of T cell co-stimulation). In mice that had autoantibodies but still no clinical arthritis, representing a setting in which autoimmunity has developed but not yet clinical arthritis, treatment was also effective. Methotrexate seemed to be more effective than TNF inhibition in this setting, although the different medications were not directly compared14. Among the numerous limitations of these experimental studies, two are especially relevant when considering preventive treatment: first, the treatment period in most experiments was extended into the clinical phase and not confined to the pre-arthritis phase, and second, the outcome was arthritis severity and not the development of clinically detectable arthritis. So, although the trends in these animal studies favour the relevance of pre-arthritis treatments, larger studies with treatment confined to the pre-arthritis phase and with head-to-head comparisons of different treatments, such as methotrexate versus abatacept therapy, will yield more information on the preventive effects of DMARDs in mice.

The first placebo-controlled trial assessing the initiation of treatment in pre-arthritis in humans was published in 2009 and demonstrated that a double intramuscular injection of dexamethasone in seropositive patients with arthralgia decreased autoantibody levels, but did not prevent the development of arthritis15. In 2016, results from the PRAIRI (prevention of clinically manifest RA by B cell directed therapy in the earliest phase of the disease) trial demonstrated that a single infusion of rituximab in seropositive patients with arthralgia and any sign of systemic and/or local inflammation delayed, but did not prevent, the development of clinical arthritis (Table 1)16. Several other proof-of-concept trials are currently ongoing (Table 2). The study populations and the drugs used vary in the different trials, but the majority of the trials have as at least one of their inclusion criteria the presence of RA-related autoantibodies (an indicator of RA-associated autoimmunity). Publication of the results from these trials over the next decade will increase our understanding on whether such interventions can effectively prevent chronic arthritis and, if so, in which subsets of individuals at risk.

Table 1. Performed proof-of-concept treatment studies in patients with arthralgia.

| Study reference | Year of publication | N of subjects | Participants | Intervention | Outcome measures | Follow-up duration | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bos et al15 | 2009 | 83 | Patients with arthralgia who were either ACPA-positive or rheumatoid factor-positive, and had the presence of the shared epitope | Intramuscular injection of either dexamethasone (100 mg) or placebo at 0 and 6 weeks | Primary outcome: 50% reduction of ACPA or rheumatoid factor levels at 6 months; secondary outcome: the development of clinical arthritis | Median 26 months (IQR 21-37) | Arthritis development was similar in both groups (20% vs 21%). In each group 50% of patients had a reduction in one or both autoantibodies; in the intervention group, autoantibody levels significant decreased after 1 month (ACPA -22%, RF -14%), which persisted at 6 months for ACPA; in the placebo group no significant decreases in autoantibody levels were demonstrated. |

| Gerlag et al.16 | 2016* | 82 | Patients with arthralgia who are positive for both ACPAs and rheumatoid factor, and have CRP levels ≥3 mg/l and/or subclinical synovitis as detected by ultrasonography or MRI of the hands | Intravenous Rituximab (1000 mg) or placebo following intramuscular methylprednisolone (100 mg) premedication | Development of clinically manifest arthritis | Median 29 months (range 0–54) | 40% of patients developed arthritis in the placebo group after a median period of 11.5 months and 34% in patients in the rituximab group developed arthritis after a median period of 16.5 months, which represented a significant delay in the development of arthritis, but not a significant prevention of arthritis. |

This table demonstrates the current absence of evidence for treating patients with arthralgia in order to prevent clinical arthritis ACPA, anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies; CRP, C-reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range

abstract publication (full article not yet published)

Table 2. Summary of ongoing placebo controlled proof-of-concept trials in pre-arthritis phases (preventive trials).

| Trial name | Year of start | Planned sample size | Participants | Intervention | Primary outcome measure | Follow-up duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APIPPRA65 | 2014 | 206 | Patients with non-traumatic arthralgia who are autoantibody-positive (that is, are either positive for both rheumatoid factor and ACPAs or have high levels of ACPAs) | Abatacept (125 mg, weekly subcutaneous injections) over 12 months | Development of either clinical arthritis or RA | 24 months |

| ARIAA66 | 2014 | 95 | Patients with arthralgia who are positive for ACPAs and have subclinical inflammation in the dominant hand as detected by MRI. | Abatacept (125 mg weekly subcutaneous injections) over 6 months | Improvement of inflammation | 18 months |

| TREAT EARLIER67 | 2015 | 200 | Patients with clinically suspect arthralgia and subclinical MRI-inflammation in the most painful hand and/or foot | Methylprednisolone (120 mg single intramuscular injection) and methotrexate (25 mg, weekly)over 12 months | Development of clinically-detectable arthritis (≥2 involved joints and persisting for ≥4 weeks) | 24 months |

| STAPRA68 | 2015 | 220 | Auto-antibody positive patients (that is patients who are either positive for both rheumatoid factor and ACPAs or have high levels of ACPA | Atorvastatin (40 mg daily) over 36 months | Development of clinically-detectable arthritis` | 48 months |

| StopRA69 | 2016 | 200 | ACPA-positive individuals without inflammatory arthritis; these patients are either FDRs of patients with RA, individuals recruited at health-fairs or individuals recruited from rheumatology clinics | Hydroxychloroquine (200–400 mg daily) over 12 months | Development of clinically-apparent RA | 36 months |

ACPA, anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies; FDR, first-degree relative; RA, rheumatoid arthritis;

Until positive results are obtained from any these proof-of-concept studies, no evidence is available to support the use of DMARDs in patients without clinical arthritis, which is in line with published recommendations1,2. However, as such patients might already be experiencing pain and functional limitations, prescribing NSAIDs or other pain killers to reduce pain seems logical, as is closely monitoring these patients for the development of clinical arthritis.

The importance of risk stratification

Risk stratification is an essential strategy for advancing research in RA prevention. Adequate risk stratification is crucial when designing and interpreting the results of preventive studies; within the study population, the risk each individual has of developing the disease outcome (such as clinically-evident RA) considerably affects the power of the study. The greater the percentage of individuals included in the study that have a low risk of developing RA within one or two years (known as ‘non-informative’ inclusions), the lower the power of the study. This phenomenon is especially notable in trials of relatively low samples sizes, such as some of the preventive trials performed over the last decade15,16. The importance of risk stratification was illustrated in 2017 in a post-hoc analysis of the PROMPT (probable RA: methotrexate versus placebo treatment) trial17,18. In this trial, patients with undifferentiated arthritis were randomized to receive either methotrexate or placebo in order to either prevent the development of RA (the primary outcome) or achieve drug-free remission (the secondary outcome)17. Analysis of the whole group showed that methotrexate treatment neither prevented RA development nor resulted in drug-free remission. Initial post-hoc analysis suggested, however, that methotrexate had a beneficial effect in anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA)-positive patients but not in ACPA-negative patients. But although the ACPA-positive patients had a higher risk of developing RA than ACPA-negative patients, stratifying patients based solely on ACPA status was still too simplistic17. Previous studies investigating the natural course of undifferentiated arthritis have shown that only one-third of these patients will develop RA, whereas others develop different diagnoses or go into spontaneous remission19,20. Investigators, hence, subsequently developed and validated a model that predicts the risk of an individual patient with undifferentiated arthritis progressing to RA, taking into account data on clinical features, the presence of rheumatoid factors or ACPAs and levels of C-reactive protein (CRP)21,22. When repeating the analyses of the PROMPT trial considering only those patients predicted to have a high risk of RA by this model (>80% in the next year; referred to here as ‘high-risk’ patients), methotrexate was shown to prevent RA development (with a number needed to treat of two)18.

The PROMPT trial was performed before the development of the 2010 ACR–EULAR classification criteria for RA23. Therefore, the secondary outcome, DMARD-free remission, is of importance as this outcome was independent of classification criteria. Interestingly, methotrexate treatment increased the proportion of high-risk patients who achieved DMARD-free remission after 5 years of follow-up (none (0%) of the 11 patients in the placebo group versus four (36%) of the 11 patients in the methotrexate group)18. Further stratification of these high-risk patients by ACPA-status showed a preventive effect in both ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative patients, whereas no effect was observed in ACPA-positive or ACPA-negative patients at a lower risk of developing RA (indicating that these two latter groups contained predominantly non-informative inclusions). In other words, the previous conclusion that methotrexate might only work in ACPA-positive patients with undifferentiated arthritis was due to the fact that this group of patients included a higher proportion of high-risk patients than the group containing ACPA-negative patients with undifferentiated arthritis. Altogether, these data highlight the importance of patient stratification: only when studying patients with a high risk of developing RA was the important preventive effect observed. These results are based on post-hoc analyses with small numbers of patients, but they underline the relevance of adequate prognostication in prevention trials in order to avoid false-negative trial results.

Shared decision-making between physicians and patients requires the physician to adequately inform the patient about their risk of developing RA. In the last 2 years, qualitative studies have revealed that individuals at risk of developing RA have difficulties interpreting their probability of future RA-development when it is expressed as a percentage, and prefer to receive a yes or no answer regarding whether or not they will develop RA24–25. This finding implies the most appropriate risk prediction tools to use, when in discussions with patients in the pre-arthritis phase about whether to initial treatment, are those with high positive and negative predictive values (that is, tests with a clear-cut readout).

Translating research into clinical practice also depends on appropriate risk stratification. If the ongoing proof-of-concept studies are successful and support the treatment of patients with arthralgia in order to prevent clinically-apparent arthritis, the next question will concern whom to treat. Insufficient risk stratification at the time that positive proof-of-concept trial results emerge might result in overtreatment of patients, and include treating patients that are only considered at some risk of developing RA. This overtreatment is highly undesirable, both from the perspective of individual patients and from the socio-economic point of view. Thus, adequate risk stratification is crucial.

Perceptions of preventive treatment

Interpreting and communicating the risks and benefits of a treatment strategy with patients is complicated, particularly in the setting of preventative trials, as not only is the efficacy and safety of a particular treatment strategy uncertain, so is the baseline risk of the patient population developing RA. Therefore, studies evaluating patient perceptions should include a multidisciplinary team of patients, health professionals and rheumatologists.

The importance of patient communication is illustrated by the results of one trial investigating the benefits of personalized risk education; in this trial, those individuals at risk of RA who received personalized risk education, which incorporated factors such as smoking, diet, exercise, or dental hygiene, were more motivated to change their health behaviours than individuals who receive standard education about RA26.

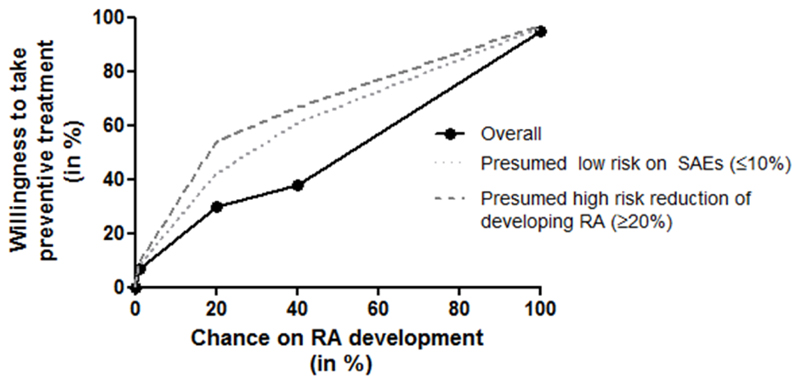

A patient’s perception of the risk and benefits of preventive treatment can affect their willingness to take such medication. As mentioned above, individuals prefer a yes or no answer on the question of whether they will develop RA23–25. In 2016, a Swiss study evaluated, from the perspective of individuals at risk of developing RA (that is, 32 asymptomatic first-degree relatives (FDR) of patients with RA), what levels of risk justify the initiation of treatment, and which factors influence this decision27. Initially, the investigators assigned all participants a hypothetical baseline risk of developing RA. The participants were then presented with hypothetical scenarios, involving potential preventive treatments in combination with a number of treatment attributes of different levels (extent of risk reduction, risk of mild and serious adverse events and mode of administration), and asked whether they would be willing to take the preventive treatment. Overall, the willingness to take preventive medication increased in parallel with the risk of developing RA; 38% of the relatives studied would be willing to take medication if the risk of RA was 40% whereas 30% and 7% would be willing to take preventive medication if the risks of RA were set at 20% and 1%, respectively. Attribute analyses revealed that the odds of accepting preventive treatment were significantly higher if treatment was associated with a ≥20% risk reduction of developing RA compared with treatment that only delayed RA development, and was also higher for treatment associated with a lower risk of serious adverse events (≤10%) compared with a higher risk (>10%). Interestingly, several factors showed no association with willingness to take preventive medication (that is, these factors did not seem to influence the individual’s decision), including a delay in the onset of RA (instead of its prevention), a risk of mild adverse events, and the mode of administration of the medication (oral, injection, infusion)27. Although larger studies on this subject are needed, as well as studies of individuals considered at risk because of their symptoms rather than because they have a FDR with RA, these data highlight the important influence patient perceptions have on willingness to take preventive medication and the contributing factors that should be taken into account when designing preventive trials and translating findings into clinical practice. Studies in the field of oncology and cardiovascular diseases have shown that adherence to preventive medications is rather poor and hence patient willingness to take such medication is of utmost importance28,29.

RA prevention in clinical practice

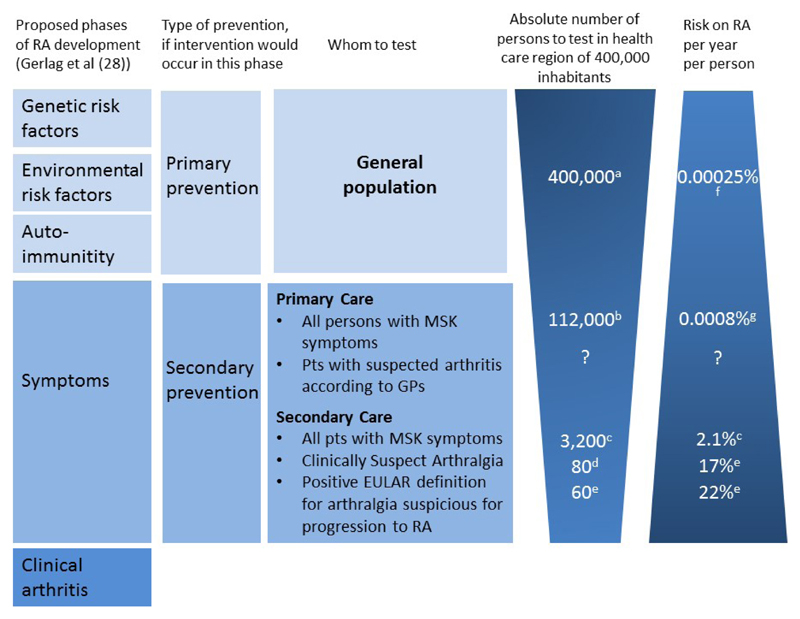

Disease prevention in different healthcare settings

Disease prevention includes a wide range of procedures and interventions, all aimed at reducing the risks and threats to patient health. Primary, secondary and tertiary prevention are different in nature (Figure 2)31. Primary prevention aims to prevent disease before it occurs and can be directed at either the whole population, individuals at high risk of disease as a result of a particular exposure (for example, individuals with specific genetic risk factors or individuals that smoke) or individuals of a specific age or gender. Examples of primary prevention are the immunization of young children and the screening and treatment of hypertension in a high-risk population (for example, individuals predicted to be at high risk based on their age, BMI and/or ethnicity) to prevent future cardiovascular events. In addition, screening for the presence of certain serological factors (for example, RA-related autoantibodies) in the general population or in FDRs of patients with RA, who have a three to four-fold increased risk of developing RA, can be considered as a test used for primary intervention. Despite the increased disease risk associated with such patients, the absolute risk of an asymptomatic individual in the general population developing disease is low, as is the absolute risk of family members of patients with RA32–34. However, the features of primary prevention are outside the scope of this Review, and are not discussed further.

Figure 2. Willingness of persons at risk for RA to take preventive medication, and factors influencing this willingness, schematic representation of data published by Finckh et al (25).

The black line is based on the reported results that 7%, 30% and 38% of persons at risk of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) were willing to take medication if the risk on RA was set at respectively 1%, 20% and 38%.(25) Qualitative studies have shown that persons prefer to receive a yes/no answer on whether or not they will progress to RA (22–24) and therefore, if the risk on RA was 100% the willingness of taking medication was set at 95%. Low risk on severe adverse events (SAEs) (≤10%) and high risk reduction of developing RA (≥20%) significantly increased the willingness to take preventive medication which is schematically depicted by the grey lines; reported odds ratios for willingness to take preventive medication were around 4 if risk on SAEs was low and around 7 if the risk reduction of developing RA was high; the odds ratios here depended also on the absolute chance on RA development.(25)

Secondary prevention aims to reduce the symptoms of a disease that has already occurred, such as joint pain. This process involves detecting and treating the disease as soon as possible to halt (or slow) disease progression. An example of secondary prevention is the regulator screening of women over the age of 50 years for breast cancer by mammography. Although the phase in which RA starts is not completely clear, interventions performed in the symptomatic phase of arthralgia (the phase preceding clinical synovitis) can be considered a form of secondary prevention (Figure 2). Tertiary prevention aims to soften the effects of an ongoing disease; in the case of RA, tertiary prevention concerns patients with clinical arthritis and/or RA, which is also beyond the scope of this Review.

Secondary intervention of patients who might progress to RA begins with the identification of patients with arthralgia; however, not all patients with arthralgia are similar, and the balance of whether or not to screen and/or treat a patient with arthralgia will depend on the pretest probability that a patient has an inflammatory form of arthralgia, which can vary depending on the healthcare setting (as discussed below).

Identifying patients at risk of developing RA

Patients at risk of developing RA can be identified by different approaches depending on the healthcare setting (Figure 2). Screening for and secondary intervention of patients with arthralgia can be performed in a primary (the general practice surgery) or secondary (the rheumatology outpatient clinic) healthcare setting. In primary care, interventions can be performed on all patients that present with any type of musculoskeletal symptoms. Although the exact numbers of individuals with musculoskeletal symptoms are unknown, such symptoms are a common complaint in primary care. However, for the vast majority of these patients, these symptoms will be unrelated to (imminent) RA, and, although the exact numbers are unknown, the proportion of these patients that have suspected arthritis will likely be small. In the United Kingdom, patients with RA have been reported to visit their general practitioner up to eight times before being referred to secondary care36; nonetheless, patients with (imminent) RA comprise a very small proportion of all patients visiting general practitioners with musculoskeletal symptoms.

Only some patients with any form of musculoskeletal symptoms are referred to secondary care, as patients are generally only referred if the GP judges that they have a decent pre-test probability of developing an inflammatory disease. Although referral criteria have been proposed for identifying patients with suspected early RA, such as the presence of metatarsophalangeal and/or metacarpophalangeal involvement, and morning stiffness of ≥30 minutes(37), most general practitioners differentiate patients using their expertise. Although fewer patients with musculoskeletal symptoms visit secondary care than primary care, this population is still heterogeneous. Patients with either clinical arthritis or evident RA represent only a small proportion of those patients with musculoskeletal symptoms that are referred to secondary care38. Similarly, only a small proportion of these patients are considered to have clinically-suspect arthritis (CSA; that is, patients with arthralgia without clinical arthritis but considered to be at risk of developing RA based on their clinical presentation. Dutch observational study showed that patients with CSA comprised only 6.5% of all patients that present to rheumatologic care without clinical arthritis and with arthralgia that was otherwise unexplained39. In secondary care, pattern recognition and clinical expertise are important for differentiating patients with arthralgia who are at risk of developing RA from patients with other types of arthralgia.

In other words, not all patients with arthralgia are similar and the probability of a patient with arthralgia developing subsequent RA varies depending on the setting the patient is selected from (figure 2). Patients with CSA, who have a higher probability of developing RA than a typical patient with arthralgia, constitute only a small subgroup of patients with arthralgia presenting in secondary care. Importantly, a study in 2016 reported that clinical expertise (that is, the judgement that a patient has CSA) has a high sensitivity for identifying at-risk patients in secondary care (80%), and that few patients that present with arthralgia and later-on progress to RA are missed by their rheumatologists38. In summary CSA seems to define a subpopulation of patients with joint pain that have a higher chance of developing RA

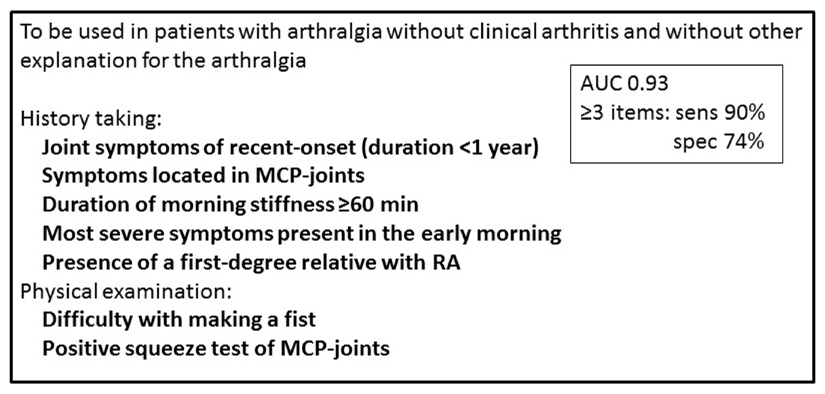

Although clinical expertise is regularly used in daily care, its subjectivity is an obvious drawback for scientific studies. Hence a EULAR taskforce set-out to explicate this particular clinical expertise in defined measurable terms and reached a definition for “arthralgia suspicious for progression to RA”40. This definition is to be used in secondary care in patients with arthralgia in whom rheumatologist consider imminent RA more likely than other diagnoses (that is, patients with CSA). The clinical definition consists of seven items; five obtained by history taking and two by physical examination (Box 1). Healthcare systems over the world are organised differently, with primary care being managed either by general practitioners or by organ specialists (such as internists, gynaecologists, orthopaedists or surgeons), resulting in different populations of patients with arthralgia. However, all these healthcare systems have rheumatologists who see patients suspected of developing RA and therefore the EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to RA is applicable in almost all health care systems. The aim of this definition is to harmonize what group of patients rheumatologists consider being at risk of developing RA. Indeed, data have revealed that this definition serves well to exclude some patients that (despite a rheumatologist’s suspicion of imminent RA) actually had a low risk of RA. Additionally, the application of this definition in patients with CSA identified a subgroup of patients with a slightly higher risk of subsequent RA compared with the remaining patients with CSA41.

Box 1. EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to rheumatoid arthritis38.

A sensitive definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to rheumatoid arthritis (RA) requires the presence of at least three of the seven items listed below*. A specific definition requires the presence of at least 4 of these items. This definition is designed be used in patients with arthralgia without clinical arthritis and without another explanation for the arthralgia.

History taking

Joint symptoms of recent onset (duration <1 year)

Symptoms located in metacarpophalangeal joints

Duration of morning stiffness ≥60 min

Most severe symptoms present in the early morning

Presence of a first-degree relative with RA

Physical examination

Difficulty with making a fist

Positive squeeze test of MCP-joints

*The reported area under the curve (AUC) of this combination of parameters is 0.93. The sensitivity and specificity of this combination of parameters in the presence of ≥3 items is 90% and 74%, respectively. These values were calculated in a validation study with the clinical expertise of a group of European expert rheumatologist that evaluated patients in their own practices as reference40

Figure 4. EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to rheumatoid arthritis (38).

AUC: area under receiver operating characteristic curve; sens: sensitivity; spec: specificity; MCP: metacarpophalangeal; RA: rheumatoid arthritis

A sensitive definition requires the presence of at least three items. A specific definition requires the presence of at least 4 items.

The reported AUC and sensitivity were calculated in a validation study with the clinical expertise of a group of European expert rheumatologist that evaluated patients in their own practices as reference.(38)

In conclusion, selecting patients with arthralgia and a high risk of developing RA, such as patients fulfilling the EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to RA, might offer an optimal starting position to investigate the mechanisms underlying this phase of RA development or designing preventive trials.

Predicting disease risk in different healthcare settings

Selecting the correct subgroup of individuals to test (risk stratification) is essential as this selection can influence the post-test probability of the tested population developing RA. This general principle is exemplified when considering ACPA-status as a predictive indicator of RA development (Table 3). In the general population, the risk of ACPA-positive individuals developing RA over 5 years is estimated to be ˜5%, with a life time risk of 16%6,7. The prevalence of ACPA-positive individuals in the general population is 1-2%42–44, and the results from a longitudinal study in this setting suggest that the presence of ACPAs in symptom-free individuals is associated with an 8.5% risk of developing RA after ˜3 years of follow-up42. These findings mean that 91.5% of individuals that are positive for ACPAs will not develop RA in the forthcoming years (and hence these patients will have false-positives diagnoses when using ACPA status as a predictive measure for RA development). Based on the prevalence of ACPA-positive individuals and the positive predictive value (PPV) of ACPA testing in the general population, the number of individuals in the general population that need be to tested in order to identify one patient who will develop RA can be estimated at ˜1200.

Table 3. Positive predictive value of ACPA testing for RA-development in different settings as observed in longitudinal studies.

| Setting | Prevalence of ACPA-positive individuals | PPV of ACPA testing for RA-development* | Estimated number of patients needed to test to identify one patient with RA‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population-wide | 1-2%42–44 | 8.5% during a median of 3 years follow-up 42 | ~1200 |

| Patients with musculoskeletal symptoms | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| Patients with CSA | 16%11 | 63% within 1 year follow-up11 | 10 |

For patients presenting with musculoskeletal symptoms in primary care, and unselected patients with musculoskeletal symptoms in secondary care, the prevalence of ACPA, the PPV of ACPA testing of such patients and the NNT to identify one patient who will develop RA is unknown.

Estimated PPV based on the number of ACPA-positive individuals who developed RA in the specified period.

Estimated NNT based on the prevalence and PPV; in the setting of the general population, the calculation was performed with a prevalence of 1%.

Several studies on ACPA-positive arthralgia have been performed in different settings (health fairs, primary care, secondary care and/or a combinations of these settings)45–47. The PPV of ACPA testing for RA-development over 1 year ranged, in these studies, between 20–34%45,46,48. As the number of individuals that underwent ACPA-testing was not reported, the number needed to be tested in order to identify a patient that will progress onto developing RA cannot be estimated. 16% of patients with CSA are estimated to be ACPA-positive11, and a positive ACPA-test in such patients is associated with a 63% risk of developing clinical arthritis within one year; thus, in this subset of patients the risk of a false-positive test result, when using ACPA-status as a predictor of arthritis development within one year, is 37%. Based on these data, the number of patients with CSA that need to be tested to identify one ACPA-positive patient who develops RA within one year is ten. Hence, the higher the a priori risk of developing RA, the higher the predictive value of ACPA-testing is for subsequent RA development (that is, the higher the PPV and lower the risk of false-positivity) and thus the lower the number of individuals that need to be tested to identify one patient who will develop RA (Table 3). Hopefully, incorporating measurements of other structural features of ACPA, such as the presence of specific glycans in the Fab or Fc domain of ACPA-molecules, will lead to better test performances of ACPA assays49,50.

Identifying imminent RA

Knowledge of ACPA status alone is insufficient to accurately stratify patients with arthralgia who are clinically at risk of developing RA (CSA), as the PPV of ACPA-testing is at most 63%11 (implying that ≥37% of ACPA-positive patients would have false-positive diagnoses), and up to half of the patients with newly-diagnosed RA are ACPA-negative and hence are missed by this approach (false-negatives). Patients prefer tests that have a have a very high predictive value (that is, a test that can confirm or exclude imminent RA). Hence, additional ways of stratifying patients are needed.

Studies have identified other potential biomarkers for predicting RA progression. For example, subclinical joint inflammation, either detected by MRI or by ultrasound, is a proven predictive indicator of RA development9–11,51. Further studies are required that directly compare the predictive accuracy of both imaging modalities, and that evaluate the minimal region needed to be imaged for maximal results; however, current data demonstrate that subclinical inflammation can predict RA development independently of autoantibody status and clinical features in patients with CSA, indicating that the presence of both autoantibodies and subclinical inflammation might further increase the risk of developing RA compared with each feature alone10,11. Increased levels of C-reactive protein can also independently predict RA-development in such patients11. Finally, preliminary studies investigating the predictive value of certain B cell or T cell characteristics, as well as of gene expression profiles in whole blood, have also shown promise. Although these studies require replication, these markers are of interest as they might provide further insight into the etiopathogenetic mechanisms of RA52–56.

Several ongoing studies are currently investigating other predictors of RA development, such as autoantibodies other than ACPAs and structural features of autoantibodies; these studies not only include patients with arthralgia but also first degree asymptomatic relatives of RA-patients in an attempt to look at individuals with a higher likelihood of development of RA than the general population57–60. Together these studies might provide additional information on RA development and help with the prediction of RA development in different at-risk populations.

Three separate studies have combined different types of predictors in arthralgia patients to develop a prediction model. Unfortunately, these studies investigated different patient populations (ACPA-positive patients with non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms in primary care, autoantibody-positive patients with arthralgia, and patients with clinically suspect arthralgia in secondary care) and so cannot be directly compared11,45,46. Although the results were promising, none of these models have yet been validated in independent patient populations. So, although information on different types of biomarkers are available, the use of different patient populations in these studies, which all have a different risk of developing RA, hampers the validation of each biomarker and/or model.

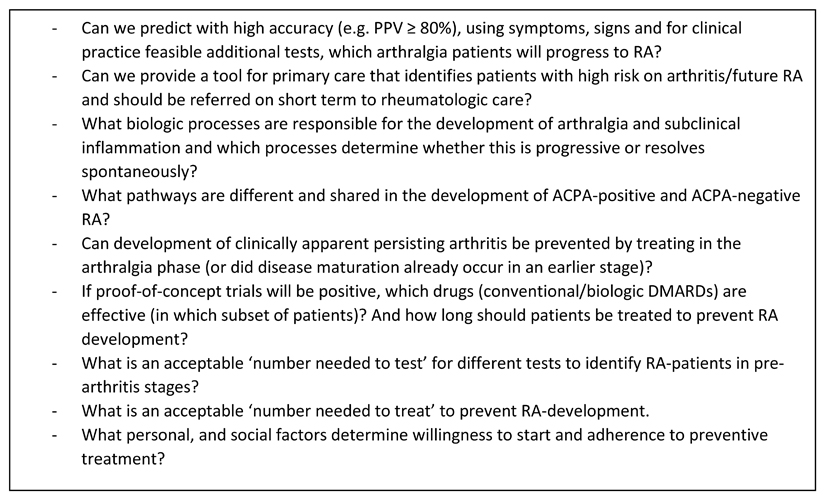

Several outstanding questions remain to be addressed when examining disease progression from arthralgia to arthritis (Box 2’. In order to be able to accurately predict RA development from the pre-arthritis phases researchers should collaborate and use similar criteria (such as the EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to RA) for evaluating clinically-relevant patient groups. The harmonization of patient selection will allow researchers to combine results of studies performed at different centres and to assess and/or validate findings from other centres. Furthermore, more extensive observational studies on the natural course of arthralgia in patients at risk of developing RA (without DMARDs treatment) are needed to improve risk stratification. This research could reveal whether physicians should initiate preventive treatment and, if so, in which groups of patients.

Box 2. Research agenda for examining the prevention of progression from arthralgia to arthritis.

For the design and interpretation of preventive studies, and translating such findings into clinical practice, several remaining questions remain to be addressed

-

-

Is it possible to predict with a high accuracy (for example, a positive predictive value of ≥80%) which patients with arthralgia will develop rheumatoid arthritis (RA), using symptoms, clinical signs and additional tests that are feasible to implement in clinical practice? And if so, how?

-

-

Will any primary care tool(s) be able to identify patients with a high risk of developing arthritis and/or future RA, who should hence be referred to rheumatologic care? And if so, which ones?

-

-

What biologic processes are responsible for the development of arthralgia and subclinical inflammation and which processes determine whether these features are progressive or will resolve spontaneously?

-

-

What are the overlapping and non-overlapping pathways that contribute to the development of anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA)-positive and ACPA-negative RA?

-

-

Can the development of clinically-apparent persisting arthritis be prevented by treating patients in the symptomatic pre-arthritis phases (or does disease maturation occur at an earlier stage)?

-

-

If proof-of-concept trials reveal beneficial effects of initiating treatment in the pre-arthritis phase, which drugs are most effective (and in which subset of patients)? And how long should patients be treated for to prevent RA development?

-

-

What is an acceptable ‘number of patients needed to test’ for tests that identify patients with RA in pre-arthritis stages?

-

-

What is an acceptable ‘number of patients needed to treat’ to prevent RA-development.

-

-

What personal and social factors determine a patient’s willingness to start preventive treatment and adhere to such treatment?

Figure 5. Research agenda.

PPV: positive predictive value; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; ACPA: anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies; DMARD: disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

Conclusions

The development of RA is a multistep process that can be ongoing years before arthritis is present. The pre-arthritis phases might be part of the therapeutic window of opportunity and disease modulation in this phase is hypothesized to prevent clinically-apparent and persistent RA from arising. To examine whether progression from arthralgia to arthritis can be prevented, identifying the correct patients (that is, accurate risk prediction) is crucial, and should overcome false-negative study results. Currently, several different approaches for identifying at-risk populations are being tested and several trials are ongoing. However, whether disease modulation in the pre-arthritis phase has beneficial effects has not yet been demonstrated. Refining the term arthralgia and specifying the clinical characteristics of patients that have arthralgia and are at risk of developing RA, such as the EULAR definition of arthralgia at risk for RA, might reduce the heterogeneity of patients included in different studies. The EULAR definition is a sensitive predictor of RA development, and reflects the expert’s opinion of imminent RA41. Therefore, this definition might offer an optimal starting position for investigating the mechanisms underlying this phase of RA development or designing preventive trials. Further research is needed to characterize the evolution from pre-arthritis to clinically overt disease in order to establish if disease modulation in this phase is effective in preventing RA (and if so, with which drugs).

Keypoints.

-

-

Early treatment initiation in patients with clinically-manifest rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is associated with improved disease outcomes; hence, disease modulation in pre-arthritis phases might prevent the occurrence of clinical arthritis.

-

-

The inclusion of patients with a low risk of developing RA might dilute possible preventive effects and result in false negative results of preventive trials.

-

-

Although a symptomatic phase typically precedes clinical arthritis in patients who develop RA, arthralgia is common and is not specific enough to identify patients at risk of developing RA.

-

-

The EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to RA, which identifies patients with arthralgia at risk of developing RA, is a good starting position for preventive trial participant selection.

-

-

Adequate stratification of patients with arthralgia at risk of developing RA requires a combination of clinical, serological and imaging markers.

Figure 3. Different approaches of identification of persons at risk of rheumatoid arthritis.

RA: rheumatoid arthritis; MSK: musculoskeletal; GP: general practitioner

a All numbers in this figure are based on data from the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), the only referral center in a health care region of 400,000 inhabitants, and for some calculation combined with data from the local GP network practices in this health care region (RNUH-LEO).(33)

b According to NIVEL and the local GP network practices (33,39), the yearly incidence of any non-traumatic musculoskeletal symptom was 294/1,000 (based on ICPC codes L1-L20, L84-L93 and T92 in the period 2009-2013 (40)). In a region of 400,000 inhabitants, there will be approximately ˜112,000 novel consultations for MSK symptoms per year.

c 3,200 novel referred patients are seen per year at the rheumatologic outpatient clinic of the LUMC; we assumed that they all have MSK symptoms. Of these, 70 were newly diagnosed with RA within the first year (average data based on data of the Leiden Early Arthritis Cohort (the only referral centre in a healthcare region of 400,000 inhabitants) of the period 2009-2013 (41). Thus, yearly risk of 70/3200=2.1%.

d At this outpatient clinic, 145 CSA-patients were identified in 1.8 year (36); this is 80 per year.

e 75% of these CSA-patients had a positive EULAR definition and 22% progressed to RA.(42) As a reference, of all CSA-patients 17% progressed to RA within one year.(11)

f Based on an incidence of 25/100,000/year in the general population.(32)

g Calculations were based on published data from local GP network practices (33,43); these practices are part of the referral region of the LUMC. The total population here is 44,350 patients. Based on the incidence of consultations for MSK symptoms as reported at B, it is estimated that approximately 13,000 consultations for MSK complaints were performed in the GP practices yearly. During 2009-2013, 43 polyarthritis cases and 5 oligoarthritis cases were observed and confirmed.(43) Thus, an incidence of 10.2 per year per 13,000 MSK complaints consultations. This is a yearly risk of 0.0008% for this group of patients.

There are no data on the number of patients in primary care that the GPs considered as suspicious for arthritis, there is also no data on the outcome of this group.

Acknowledgement

This Review was supported by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Vidi grant) and European Research Council (ERC Starting grant). The funding sources had no role in the writing of the manuscript.

Author biographies

H.W. van Steenbergen obtained her medical degree in 2012 at the Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands (cum laude). In 2016 she received her Ph.D. in rheumatology at the Leiden University Medical Centre also in Leiden. Her main research focus is early recognition of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and imaging in (early) RA. From 2016 to 2017 she was involved in the EULAR task force that developed the definition for arthralgia suspicious for progression to RA. She has published >40 papers in international peer-reviewed journals. Since December 2015 she has been a training rheumatologist at the Leiden University Medical Centre.

J.A. Pereira da Silva received his MD. from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Coimbra, Portugal, in 1982 and his Ph.D. in medicine and rheumatology from the University College London, UK, in 1993. He has a longstanding dedication to medical education, consolidated in his activities as the chairman of the EULAR standing committee for education and training (from 2001 to 2005) and the president of the European board of rheumatology from 2006 to 2010. He has published >150 papers in national and international peer-reviewed journals and currently serves on the editorial board of several scientific journals in the area of rheumatology.

T.W.J. Huizinga received his medical degree from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, in 1986 and his Ph.D. from the same university in 1989 (cum laude). He finished his rheumatology training in the University of Leiden in 1997. He has a longstanding dedication to patient care and research and became professor of rheumatology in 2000 and the chairman of the department of rheumatology in 2007. He has published >600 papers in national and international peer-reviewed journals and currently serves on the editorial board of several scientific journals in the area of rheumatology. His H-factor is 86 and he has served on many international committees, including both EULAR and ACR committees.

A.H.M. van der Helm-van Mil obtained her medical degree in 1998 (cum laude) at the University of Leiden, Leiden, the Netherlands, where she also became a ratified internist in 2005, rheumatologist in 2006 and obtained her Ph.D. in 2006 (cum laude). She was head of the outpatient clinic at the University of Leiden from 2007 to 2016. Since 2015 she has been an appointed professor at the department of rheumatology in the Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, and at the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Her research is aimed at understanding the processes underlying disease progression in the earliest phases of RA and predicting the disease course of patients presenting with arthralgia and early arthritis. She has authored >200 articles and has received several grants and prizes.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors wrote the article, provided substantial contributions to discussions of its content, and undertook review and/or editing of the manuscript before submission.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reference List

- 1.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, Buch M, Burmester G, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Mar 1;73(3):492–509. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Combe B, Landewe R, Daien CI, Hua C, Aletaha D, Álvaro-Gracia JM, et al. 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jun 1;76(6):948–959. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boers M. Understanding the window of opportunity concept in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Jul 1;48(7):1771–4. doi: 10.1002/art.11156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Nies JA, Tsonaka R, Gaujoux-Viala C, Fautrel B, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. Evaluating relationships between symptom duration and persistence of rheumatoid arthritis: does a window of opportunity exist? Results on the Leiden Early Arthritis Clinic and ESPOIR cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 May 1;74(5):806–12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ajeganova S, van Steenbergen HW, van Nies JAB, Burgers LE, Huizinga TWJ, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-free sustained remission in rheumatoid arthritis: an increasingly achievable outcome with subsidence of disease symptoms. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 May 1;75(5):867–73. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielen MM, van Schaardenburg D, Reesink HW, van de Stadt RJ, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, de Koning MHMT, et al. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: A study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Feb 1;50(2):380–6. doi: 10.1002/art.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, de Jong BA, Berglin E, Hallmans G, Wadell G, Stenlund H, et al. Antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptide and IgA rheumatoid factor predict the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003 Oct 1;48(10):2741–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sokolove J, Bromberg R, Deane KD, Lahey LJ, Derber LA, Chandra PE, et al. Autoantibody Epitope Spreading in the Pre-Clinical Phase Predicts Progression to Rheumatoid Arthritis. PLoS ONE. 2012 May 25;7(5):e35296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van de Stadt LA, Bos WH, Meursinge Reynders M, Wieringa H, Turkstra F, van der Laken C, et al. The value of ultrasonography in predicting arthritis in auto-antibody positive arthralgia patients: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010 May 20;12(3):R98. doi: 10.1186/ar3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nam JL, Hensor EMA, Hunt L, Conaghan PG, Wakefield RJ, Emery P. Ultrasound findings predict progression to inflammatory arthritis in anti-CCP antibody-positive patients without clinical synovitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Dec 1;75(12):2060–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Steenbergen HW, Mangnus L, Reijnierse M, Huizinga TWJ, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. Clinical factors, anticitrullinated peptide antibodies and MRI-detected subclinical inflammation in relation to progression from clinically suspect arthralgia to arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Oct 1;75(10):1824–30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Steenbergen HW, Huizinga TW, van der Helm-van Mil AH. Review: The Preclinical Phase of Rheumatoid Arthritis: What Is Acknowledged and What Needs to be Assessed? Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Sep 1;65(9):2219–32. doi: 10.1002/art.38013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Nies JA, Krabben A, Schoones JW, Huizinga TWJ, Kloppenburg M, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. What is the evidence for the presence of a therapeutic window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis? A systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 May 1;73(5):861–70. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekkers JS, Schoones JW, Huizinga TW, Toes RE, van der Helm-van Mil AH. Possibilities for preventive treatment in rheumatoid arthritis? Lessons from experimental animal models of arthritis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Feb 1;76(2):458–67. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bos WH, Dijkmans BA, Boers M, van de Stadt RJ, Schaardenburg D. Effect of dexamethasone on autoantibody levels and arthritis development in patients with arthralgia: a randomised trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Mar 1;69(3):571–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerlag DM, Safy M, Maijer KL, Tas SW, Starmans-Kool M, van Tubergen A, et al. A Single Infusion of Rituximab Delays the Onset of Arthritis in Subjects at High Risk of Developing RA [abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10) Available from: http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/a-single-infusion-of-rituximab-delays-the-onset-of-arthritis-in-subjects-at-high-risk-of-developing-ra/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Dongen H, van Aken J, Lard LR, Visser K, Ronday HK, Hulsmans HMJ, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate treatment in patients with probable rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res Off J Arthritis Health Prof Assoc. 56(5):1424–1432. doi: 10.1002/art.22525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgers LE, Allaart CF, Huizinga TWJ, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. Brief Report: Clinical Trials Aiming to Prevent Rheumatoid Arthritis Cannot Detect Prevention Without Adequate Risk Stratification: A Trial of Methotrexate Versus Placebo in Undifferentiated Arthritis as an Example. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 May 1;69(5):926–31. doi: 10.1002/art.40062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison BJ, Symmons DP, Brennan P, Barrett EM, Silman AJ. Natural Remission in Inflammatory Polyarthritis: Issues of Definition and Prediction. Rheumatology. 1996 Nov 1;35(11):1096–100. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.11.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Aken J, van Dongen H, le Cessie S, Allaart CF, Breedveld FC, Huizinga TWJ. Comparison of long term outcome of patients with rheumatoid arthritis presenting with undifferentiated arthritis or with rheumatoid arthritis: an observational cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Jan 1;65(1):20–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.038471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Helm-van Mil AHM, le Cessie S, van Dongen H, Breedveld FC, Toes REM, Huizinga TWJ. A prediction rule for disease outcome in patients with Recent-onset undifferentiated arthritis: How to guide individual treatment decisions. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Feb 1;56(2):433–40. doi: 10.1002/art.22380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Helm-van Mil AHM, Detert J, Cessie SL, Filer A, Bastian H, Burmester GR, et al. Validation of a prediction rule for disease outcome in patients with recent-onset undifferentiated arthritis: Moving toward individualized treatment decision-making. Arthritis Rheum. 2008 Aug 1;58(8):2241–7. doi: 10.1002/art.23681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, 3rd, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Cohen MD, Combe B, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Sep;69(9):1580–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newsum EC, van der Helm-van Mil AH, Kaptein AA. Views on clinically suspect arthralgia: a focus group study. Clin Rheumatol. 2016 May;35(5):1347–52. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stack RJ, Stoffer M, Englbrecht M, Mosor E, Falahee M, Simons G, et al. Perceptions of risk and predictive testing held by the first-degree relatives of patients with rheumatoid arthritis in England, Austria and Germany: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016 Jun 1;6(6):e010555. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sparks JA, Iversen MD, Yu Z, Triedman NA, Prado MG, Miller Kroouze R, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of Rheumatoid Arthritis Risk Disclosure Personalized to Genetics, Autoantibodies, and Lifestyle Among Unaffected First-Degree Relatives: The Personalized Risk Estimator for RA (PRE-RA) Family Study [abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10) Available from: http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/a-randomized-controlled-trial-of-rheumatoid-arthritis-risk-disclosure-personalized-to-genetics-autoantibodies-and-lifestyle-among-unaffected-first-degree-relatives-the-personalized-risk-estimator-f/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finckh A, Escher M, Liang MH, Bansback N. Preventive Treatments for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Issues Regarding Patient Preferences. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016 Aug;18(8):51. doi: 10.1007/s11926-016-0598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith SG, Sestak I, Forster A, Partridge A, Side L, Wolf MS, et al. Factors affecting uptake and adherence to breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016 Apr 1;27(4):575–90. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 patients. Am J Med. 2012 Sep;125(9):882–887.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerlag DM, Raza K, van Baarsen LG, Brouwer E, Buckley CD, Burmester GR, et al. EULAR recommendations for terminology and research in individuals at risk of rheumatoid arthritis: report from the Study Group for Risk Factors for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 May 1;71(5):638–41. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonita R, Beaglehole R, Kjellström T. Basic epidemiology. 2nd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frisell T, Holmqvist M, Källberg H, Klareskog L, Alfredsson L, Askling J. Familial Risks and Heritability of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Role of Rheumatoid Factor/Anti–Citrullinated Protein Antibody Status, Number and Type of Affected Relatives, Sex, and Age. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Nov 1;65(11):2773–82. doi: 10.1002/art.38097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Familial associations of rheumatoid arthritis with autoimmune diseases and related conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Mar 1;60(3):661–8. doi: 10.1002/art.24328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. The Lancet. 2010 Oct 1;376(9746):1094–108. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60826-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Dungen C, Hoeymans N, Gijsen R, van den Akker M, Boesten J, Brouwer H, et al. What factors explain the differences in morbidity estimations among general practice registration networks in the Netherlands? A first analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008 Jan 1;14(s1):53–62. doi: 10.1080/13814780802436218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Audit Office. Services for people with rheumatoid arthritis. 2009 Available from: http://www.nao.org.uk/report/services-for-people-with-rheumatoid-arthritis/

- 37.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Dougados M, Kalden JR, Schiff MH, Smolen JS. Early referral recommendation for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis: evidence based development of a clinical guide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002 Apr 1;61(4):290–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.4.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Steenbergen HW, van der Helm-van Mil AH. Clinical expertise and its accuracy in differentiating arthralgia patients at risk for rheumatoid arthritis from other patients presenting with joint symptoms. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2016 Jun;55(6):1140–1. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Steenbergen HW, van Nies JAB, Huizinga TWJ, Bloem JL, Reijnierse M, Mil AHM van der H. Characterising arthralgia in the preclinical phase of rheumatoid arthritis using MRI. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jun;74(6):1225–32. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Steenbergen HW, Aletaha D, de Voorde LJJB, Brouwer E, Codreanu C, Combe B, et al. EULAR definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Mar 1;76(3):491–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgers L, Siljehult F, Brinck RT, et al. OP0073 Performance of the eular definition of arthralgia suspicious for progression to rheumatoid arthritis – a longitudinal study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2017;76:82. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hensvold AH, Frisell T, Magnusson PKE, Holmdahl R, Askling J, Catrina AI. How well do ACPA discriminate and predict RA in the general population: a study based on 12 590 population-representative Swedish twins. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jan 1;76(1):119–25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Zanten A, Arends S, Roozendaal C, Limburg PC, Maas F, Trouw LA, et al. Presence of anticitrullinated protein antibodies in a large population-based cohort from the Netherlands. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 Jul 1;76(7):1184–90. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haji Y, Rokutanda R, Kishimoto M, Okada M. Anti-cyclic citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) positivity in general population and follow-up results for ACPA positive persons [abstract] Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2016;68(suppl 10) [Internet] Available from: http://acrabstracts.org/abstract/anti-cyclic-citrullinated-protein-antibody-acpa-positivity-in-general-population-and-follow-up-results-for-acpa-positive-persons/ [Google Scholar]

- 45.van de Stadt LA, Witte BI, Bos WH, van Schaardenburg D. A prediction rule for the development of arthritis in seropositive arthralgia patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Dec 1;72(12):1920–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rakieh C, Nam JL, Hunt L, Hensor EMA, Das S, Bissell L-A, et al. Predicting the development of clinical arthritis in anti-CCP positive individuals with non-specific musculoskeletal symptoms: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Sep;74(9):1659–66. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Hair MJ, Landewé RB, van de Sande MG, van Schaardenburg D, van Baarsen LGM, Gerlag DM, et al. Smoking and overweight determine the likelihood of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Oct 1;72(10):1654–8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van de Stadt LA, de Koning MH, van de Stadt RJ, Wolbink G, Dijkmans BAC, Hamann D, et al. Development of the anti–citrullinated protein antibody repertoire prior to the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Nov 1;63(11):3226–33. doi: 10.1002/art.30537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rombouts Y, Ewing E, van de Stadt LA, Selman MHJ, Trouw LA, Deelder AM, et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies acquire a pro-inflammatory Fc glycosylation phenotype prior to the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015 Jan 1;74(1):234–41. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rombouts Y, Willemze A, van Beers JJBC, Shi J, Kerkman PF, van Toorn L, et al. Extensive glycosylation of ACPA-IgG variable domains modulates binding to citrullinated antigens in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016 Mar 1;75(3):578–85. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kleyer A, Krieter M, Oliveira I, Faustini F, Simon D, Kaemmerer N, et al. High prevalence of tenosynovial inflammation before onset of rheumatoid arthritis and its link to progression to RA—A combined MRI/CT study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016 Oct;46(2):143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Janssen KMJ, Westra J, Chalan P, Boots AMH, de Smit MJ, van Winkelhoff AJ, et al. Regulatory CD4+ T-Cell Subsets and Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibody Repertoire: Potential Biomarkers for Arthritis Development in Seropositive Arthralgia Patients? PLoS ONE. 2016;11(9):e0162101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Beers-Tas MH, Marotta A, Boers M, Maksymowych WP, van Schaardenburg D. A prospective cohort study of 14-3-3η in ACPA and/or RF-positive patients with arthralgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016 Apr 1;18(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0975-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lübbers J, van Beers-Tas MH, Vosslamber S, Turk SA, de Ridder S, Mantel E, et al. Changes in peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets during arthritis development in arthralgia patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016 Sep 14;18(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1102-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chalan P, Kroesen B-J, van der Geest KSM, Huitema MG, Abdulahad WH, Bijzet J, et al. Circulating CD4+CD161+ T lymphocytes are increased in seropositive arthralgia patients but decreased in patients with newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e79370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Baarsen LG, Bos WH, Rustenburg F, van der Pouw Kraan TCTM, Wolbink GJJ, Dijkmans BAC, et al. Gene expression profiling in autoantibody-positive patients with arthralgia predicts development of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Mar 1;62(3):694–704. doi: 10.1002/art.27294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kolfenbach JR, Deane KD, Derber LA, O’Donnell C, Weisman MH, Buckner JH, et al. A prospective approach to investigating the natural history of preclinical rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using first-degree relatives of probands with RA. Arthritis Care Res. 2009 Dec 15;61(12):1735–42. doi: 10.1002/art.24833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.National Institute for Health Research, Manchester Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit. [Accessed on 02 sept 2017]; http://www.preventra.net/

- 59.http://www.arthritis-checkup.ch/index_gb.html#. Accessed on 02 sept2017

- 60.El-Gabalawy HS, Robinson DB, Hart D, Elias B, Markland J, Peschken CA, et al. Immunogenetic Risks of Anti-Cyclical Citrullinated Peptide Antibodies in a North American Native Population with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Their First-degree Relatives. J Rheumatol. 2009 Jun 1;36(6):1130–5. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nielen MM, Spronk I, Davids R. Incidentie en prevalentie van gezondheidsproblemen in de Nederlandse huisartsenpraktijk in 2014. [accessed on 10 May 2017];Uit: NIVEL Zorgregistratie Eerste Lijn [Internet] 2017 Available from: https://www.nivel.nl/nl/NZR/incidenties-en-prevalenties. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lamberts H, Wood M. International classification of primary care. Int Classif Prim Care. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Newsum EC, de Waal MW, van Steenbergen HW. How do general practitioners identify inflammatory arthritis? A cohort analysis of Dutch general practitioner electronic medical records. 2016 May;55(5):848–53. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Rooy DP, van der Linden MP, Knevel R, Huizinga TWJ, van der Helm-van Mil AHM. Predicting arthritis outcomes—what can be learned from the Leiden Early Arthritis Clinic? Rheumatology. 2011 Jan 1;50(1):93–100. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.ISRCTN registry. isrctn.com. 2015 doi: 10.1186/ISRCTN46017566. [DOI]

- 66.US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2016 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02778906.

- 67.Nederlands Trial Register. Trialregister.nl. 2014 http://www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/admin/rctview.asp?TC=4853.

- 68.Nederlands Trial Register. Trialregister.nl. 2015 http://www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/admin/rctview.asp?TC=5265.

- 69.US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov. 2017 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02603146.