Abstract

The artificial induction of tolerance in transplantation is gaining strength. In mice, a differential role of extracellular adenosine (eADO) for regulatory (Tregs) and effector (Teffs) T cells has been proposed: inhibiting Teffs and inducing Tregs. The aim of this study was to analyze the action of extracellular nucleotides in human T cells, and moreover, examine the influence of CD39 and CD73 ectonucleotidases and subsequent adenosine signaling through adenosine 2 receptor (A2R) in the induction of clinical tolerance after liver transplantation. The action of extracellular nucleotides in human T cells was analyzed by in vitro experiments with isolated T cells. Additionally, 17 liver transplant patients were enrolled in an immunosuppression withdrawal trial, and the differences in the CD39-CD73-A2R axis were compared between tolerant and non-tolerant patients. In contrast to the mice, the activation of human Tregs was inhibited similarly to Teffs in the presence of eADO. Moreover, the expression of the enzyme responsible for the degradation of ADO, adenosine deaminase (ADA), was higher in tolerant patients with respect to the non-tolerant group along the immunosuppression withdrawal. Our data support the idea that eADO signaling and its degradation may play a role in the complex system of regulation of liver transplantation tolerance.

1. Introduction

The achievement of immune tolerance to an allogenic graft has been a field of intense research over the last decade, fueled by a critical need to avoid immunosuppression (IS)-related side effects. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been implicated in this process (1). Although the precise mechanism of action of Tregs is still under debate, several studies have shown, for example, that Tregs use several mechanisms to inhibit effector T cells (Teffs): modulation of dendritic cell function; interleukin (IL)-2 deprivation; direct cytotoxicity toward Teffs; and secretion of inhibitory cytokines, such as IL-10, IL-35 or Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (2). Interestingly, Tregs can also use the metabolism of extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to perform IS (3). ATP is released into the extracellular milieu under inflammatory responses, hypoxia, or other types of cell injury, such as in organ transplantation. Extracellular ATP is sensed by the ionotropic purinergic receptor P2X7 (P2X7R) on innate and adaptive immune cells (4) and it has been associated with allograft rejection (5–7). However, inflammation promoted by extracellular nucleotides is subject to regulation by some members of the ectonucleoside family, such as ectonucleotidase triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (CD39) and ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73) (8). CD39 degrades ATP to ADP and then to AMP. Further, CD73 degrades 5′-AMP to adenosine (ADO), which is deaminated by adenosine deaminase (ADA) to inosine (3). CD39 and CD73 are highly expressed in the plasma membranes of murine Tregs, whereas in human Tregs, CD39 is primarily expressed by immunosuppressive Tregs that express FOXP3, and CD73 is weakly present (9). This increment of ATP-metabolizing activity is critical for the immunosuppressive activity of Tregs because it facilitates the pericellular generation of ADO, a substantial component of the immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory functions of Tregs (10). ADO acts via four cell surface G-protein-coupled receptors: the P1 receptors A1, A2A, A2B and A3. Although A2BR plays some role (11), there is evidence for the major role of A2AR in the regulation of T lymphocytes based on studies with A2AR-deficient mice. These effects include the apoptosis of resting T cells, inhibition of activation-induced cell death of activated T cells, inhibition of T cell mobility, migration to lymph nodes and adhesion to the endothelium or induction of T cell anergy (10, 12, 13). Moreover, A2AR agonists attenuated allograft rejection and alloantigen recognition by an action on T lymphocytes (14). However, while A2AR stimulation on murine Teffs directly inhibits their activation, A2AR stimulation expanded Tregs, which also expressed CD39, CD73 and Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 (CTLA-4). Thus, A2AR stimulation numerically and functionally enhanced a Treg-mediated immunosuppressive mechanism (15). Additionally, T cell stimulation in the presence of A2AR agonist induced FOXP3 and Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) mRNA in T cells, suggesting newly induced Tregs (iTregs) (13).

Similarly, there has been a discussion on how ADO exerts its differential function over T cells; although cyclic AMP (cAMP) and low IL-2 levels are key (16), the precise mechanism remains unsolved. Sitkovsky (17) proposed a system by which the cAMP-elevating A2R and the cAMP response element (CRE)-mediated transcription in Tregs and Teffs play key roles in this model. Nevertheless, inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) could have an important role, as it has been described a potential involvement of ICER in Treg-mediated suppression of IL-2 production in responder CD4+CD25– T lymphocytes (18).

However, these data are based on murine experiments, whereas there are few studies analyzing the differential response of human T cells towards extracellular nucleotides. The aim of the present study was to determine the capacity of ADO to impair the proliferation and activity of human Teffs while improving Treg capacities, similar to murine cells. Similarly, we analyzed the immunosuppressant capacity of a new inactive, phosphorylated form of the A2AR agonist, 2-(cyclohexylethylthio)-AMP, which is de-phosphorylated by CD73 in an inflammatory environment. Moreover, we studied the influence of ADO signaling through activation of the CD39-CD73-A2R axis in the induction of clinical tolerance after liver transplantation in samples obtained from non-tolerant and operationally tolerant liver recipients during IS withdrawal.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and purification of T cells

Blood from healthy volunteers was collected upon informed consent for T cell purification and in vitro studies. Total T cells were purified from PBMCs using the Human CD3+ T Cell Enrichment Column (R&D Systems). The purity of T cells was 94.4 ± 1.7 %. Tregs and CD4+CD25- T conventional (Tconv) cells were separated by using the EasySep™ Human CD4+CD127lowCD25+ Regulatory T Cell Isolation Kit (StemCell Technologies) (85.8 ± 5.5 and 93.6 ± 2.1 % of purity, respectively).

2.2. Culture conditions

1-5 x 105/ml isolated T cells were cultured in ImmuneCult-XF T Cell Expansion Medium with ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activator (StemCell Technologies) for 4 days at 37 ºC and 5 % CO2. When isolated Tregs or Tconv were cultured alone and where indicated, 200 U/ml human IL-2 were added to the culture. When a second round of stimulation was performed, cells from the first culture were extensively washed, counted and re-cultured for another 4 days. Media and/or cells were harvested at different time points depending on the type of analysis required. Nucleotides and/or inhibitors were added at the beginning of the culture.

2.3. Proliferation assays

Responder T cells were stained with 5 μM carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) for 15 min prior to cell culture. After appropriate culture conditions, the proliferation index (PI) was determined by flow cytometry (FC) gating for total CD4+ T cells or CD4+FOXP3highTregs and CD4+FOXP3dim/- Teffs. When isolated Tregs or Tconv were proliferated alone the PI was determined by colorimetric Cell Proliferation ELISA BrdU (Roche).

2.4. Treg suppressive assay

Isolated responder Tconv (RCs) were autologous to isolated suppressor Tregs (S). RCs were stained with CFSE, whereas S were cultured for 24 h in the presence or absence of 30 μM ADO. Subsequently, S were extensively washed and added to RCs at R:S ratios of 1:0.5 and 1:1 in a complete medium containing IL-2 (150 IU/mL) and ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28 T Cell Activator in 96-well plates and then co-cultured for 4 days. After harvest, the suppression of CFSE-labeled RCs proliferation was analyzed by FC.

2.5. Patients

A total of 22 liver transplant (LT) patients and 12 healthy donors (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1) participated in the present study under informed consent, and a non-randomized prospective IS weaning trial was approved by the ethical committee of the Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca (Murcia, Spain - PI12/02042) and conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. For detailed IS withdrawal protocol and blood samples see Supporting Information or visit www.isrctn.com Clinical Trial number ISRCTN15775356.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

| Groups |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy (n = 12) | Non-Tol (n = 12) | Tol (n = 5) | P | |

| Age [Mean ± SE; median (range)] | [64 ± 0.7; 63.5 (60-68)]** | [70.8 ± 1.2; 70.5 (63-78)] | [70.6 ± 3; 71 (61-80)] | 0.958 |

| Age at transplantation [Mean ± SE; median (range)] | - | [62.4 ± 1.3; 63.5 (56-71)] | [58.6 ± 2.2; 59 (52-65)] | 0.186 |

| Years from transplant to weaning start [Mean ± SE; median (range)] | - | [6 ± 0.9; 5 (4-14)] | [9 ± 1.3; 9 (6-12)] | 0.047 |

| Gender (n; %) | 0.472 | |||

| Male | (8; 67) | (9; 75) | (3; 60) | |

| Female | (4; 33) | (3; 25) | (2; 40) | |

| Basal AST (U/ml) [Mean ± SE; median (range)] | [18.8 ± 1.2; 18 (14-29)] | [19.7 ± 1.4; 17 (14-30)] | [18.5 ± 1.1; 18.5 (15-22)] | 0.527 |

| Basal ALT (U/ml) [Mean ± SE; median (range)] | [17.4 ± 1.6; 16.5 (9-29)] | [18.3 ± 1.4; 17 (11-29)] | [16.8 ± 2.3; 18 (8-21)] | 0.591 |

| Co-morbid medical problems (n;%) | ||||

| Diabetes | - | (5; 42) | (1; 20) | 0.395 |

| Hypertension | - | (9; 75) | (2; 40) | 0.205 |

| Hyperlipidemia | - | (5; 42) | (1; 20) | 0.395 |

| Renal dysfunction | - | (2; 17) | (1; 20) | 0.676 |

| Diseases (n; %) | ||||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | - | (7; 58) | (3; 60) | 0.686 |

| HBV | - | (2; 17) | 0.485 | |

| Cryptogenic liver cirrhosis | - | (3; 25) | (2; 40) | 0.472 |

| Drug-based IS (n; %) | ||||

| Cyclosporine A | - | (3; 25) | (2; 40) | 0.472 |

| Tacrolimus | - | (9; 75) | (3; 60) | 0.472 |

| Basal CNI concentration (ng/ml) [Mean ± SE; median (range)] | ||||

| Cyclosporine A | - | [61.5 ± 11; 61.5 (50.5-72.5)] | [57.1 ± 11.7; 57.1 (45.4-68.7)] | 0.667 |

| Tacrolimus | - | [7 ± 0.7; 7.3 (4.5-10.9)] | [8.3 ± 0.2; 8.5 (8-8.5)] | 0.067 |

| Complementary IS | ||||

| Mycophenolate mofetil | - | (6; 50) | (2; 40) | 0.563 |

| Prednisolone | - | (2; 17) | 0.485 | |

| Everolimus | - | (1; 20) | 0.294 | |

ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase ; CNI: Calcineurin inhibitor; HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

Healthy volunteers were significantly different in age (p = 0.014) compared with patients.

The mean age for both LT patient groups was 71 years old, with a mean age at transplantation of 59 and 62 years old, respectively. Although there was a statistically significant difference in age between the healthy subjects and patients (p = 0.01), no other baseline parameters showed any difference among groups (data not shown). In accordance with previous studies (19, 20), the Tol group had a longer time from transplant to IS weaning compared with the non-Tol group (9.0 ± 3.0 and 6.0 ± 2.9 years, respectively. p = 0.047). All the transplant patients received calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) as a basal IS (71 % Tacrolimus; 29 % Cyclosporin A), typically in a dual therapy with a complementary drug (mycophenolate mofetil (47 %); prednisolone (12 %) and everolimus (6 %)).The most frequent underlying disease previous to transplantation was alcoholic cirrhosis (59 %), followed by cryptogenic cirrhosis (29 %) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) (12 %); the principal co-morbid medical problems detected in these patients were hypertension (65 %),diabetes or hyperlipidemia (35 %) and renal dysfunction (18 %) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1).

2.6. Flow cytometry

All samples were subjected to flow cytometry analysis in a BD FACSCanto flow cytometer and FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) by gating for singlets based on forward and side scatter parameters. The data were analyzed by FCS Express 5 software (DeNovo Software). Detailed flow cytometry experiments can be read in the Supporting information.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The homogeneity of variances (homoscedasticity) was analyzed with the F test. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni's post-test was used whenever parametrical testing applied (normal distribution and homoscedasticity), and the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's post-test was used when the data set had to be analyzed with a nonparametric test. The evolution of variables in each group of patients was analyzed by a Friedman test. A two-way ANOVA for matched values with Bonferroni's post-test was used to compare both groups of patients. Two-tailed p values less than 0.05 were regarded as significant. Correlation analyses were evaluated using Spearman’s correlation. The statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software Inc.).

3. Results

3.1. Extracellular nucleotides inhibit human CD4+ T cell proliferation after its degradation to ADO

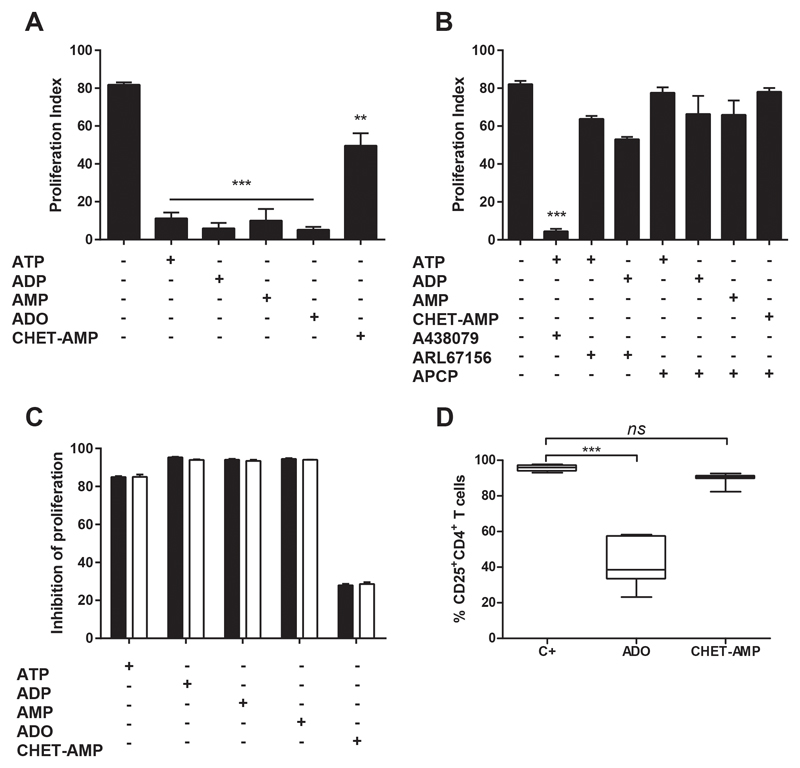

First, we examined the effect of extracellular nucleotides in the in vitro proliferation of human T cells after classical activation with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the absence of added IL-2. To this end, we followed the proliferation of CFSE-stained CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry (Figure S1A). As shown in Figure 1A, all added nucleotides (ATP, ADP and AMP), and even the nucleoside ADO, inhibited the CD4+ T cell proliferation, as well as the IFN-γ and IL-2 production (Figure S1B). These results were also obtained in the presence of 2-(cyclohexylethylthio)-AMP (CHET-AMP) (Figure 1A and Figure S1B), an inactive A2AR agonist, which requires CD73 de-phosphorylation to its active form, CHET-ADO (21) (Figure S1C) and which is able to avoid classical A2R agonist side effects, such as hypotension (22). The activation of P2X7R by extracellular ATP was discarded, as the use of its specific antagonist A438079 had no effect on T cell proliferation inhibition (Figure 1B). However, the inhibition of the degradation of ATP and ADP by blocking the activity of CD39 by ARL67156 or the de-phosphorylation of AMP or CHET-AMP inhibiting CD73 with APCP, completely reverted the inhibition of T cell proliferation exerted by these nucleotides, suggesting ADO as responsible for this inhibition (Figure 1B). The addition of recombinant human IL-2 to the culture had no any effect on the ADO-dependent inhibition of proliferation (Figure 1C). Likewise, the CD25 expression in CD4+ T cells after of activation was down-regulated in the presence of ADO (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Effect of extracellular nucleotides in human CD4+ T cell proliferation.

A-B) Percentage of proliferating total CD4+ T cells as analyzed by flow cytometry. T cells were gated for live cells and then for CD4+ cells, and the loss of CFSE fluorescence was acquired in FL1 channel as shown in Figure S1A. Cultures were performed over 4 days by CD3/CD28 engagement in the presence of 100 μM ATP, ADP, AMP, ADO or CHET-AMP (A-B), as well as 50 μM A438079, 50 μM ARL67156 or 10 μM APCP (B) where indicated. C) Inhibition of the proliferation of CD4+T cells after 4 days of culture with anti-CD3/CD28 and the indicated nucleotide/nucleoside or CHET-AMP. Cultures were performed in the presence (white bars) or absence (black bars) of 200 U/ml recombinant human IL-2. d) Percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing CD25. Cultures were performed as in A in the absence (C+) or presence of ADO or CHET-AMP. n ≥ 4 in all experiments. The results are presented as the means ± SD. **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ns = non-significant.

3.2. ADO inhibits the proliferation of Tregs similar to Teffs

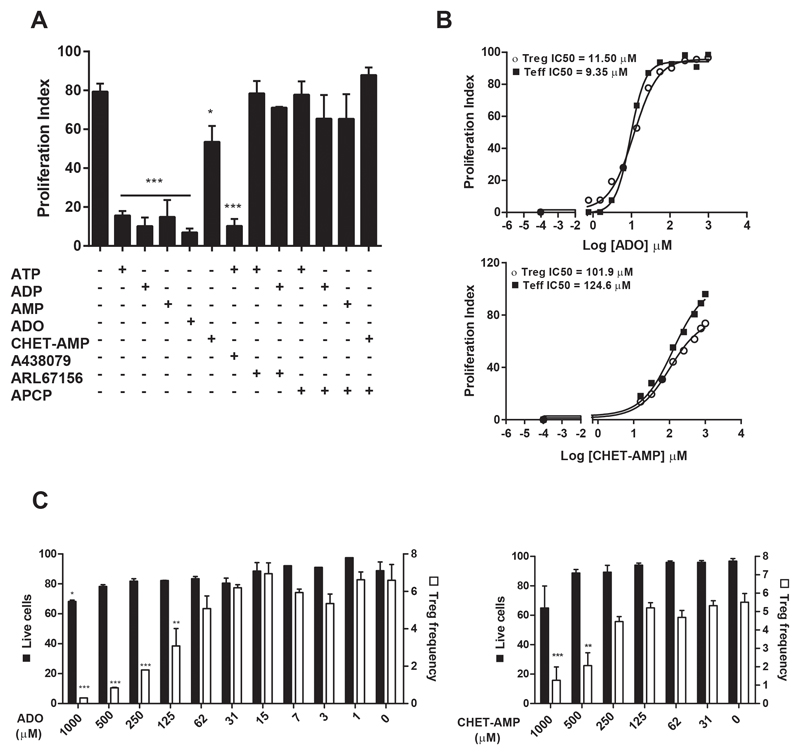

We further analyzed the evolution of Tregs gating for CD4+FOXP3high cells on the in vitro activated T cells (23) (Figure S2A). Thereby, we observed the same profile of inhibition of the proliferation as for total CD4+ T cells (Figure 2A), although the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for ADO was slightly higher, but not statistically significant, for Tregs (11.50 μM) than for Teffs (9.35 μM) (Figure 2B). Similar IC50 values were obtained for the other nucleotides (Figure S2B). However, CHET-AMP was not as effective as ADO, reaching an IC50 of approximately 100 μM for both T cell populations (Figure 2B). No changes in the viability of Tregs or Teffs was observed at low nucleotide concentrations (30 μM) (Figure S2C); nevertheless, higher concentrations of ADO and CHET-AMP affected the viability and particularly Treg frequency in the culture (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Effect of extracellular nucleotides in human Treg proliferation.

A) Percentage of proliferating Tregs as analyzed by flow cytometry. Tregs cells were gated for live cells and then for CD4+FOXP3high cells, and the loss of CFSE fluorescence was acquired in FL1 channel as shown in Figure S2A. Cultures were performed as in Figure 1A. B) The IC50 for ADO and CHET-AMP was calculated by adding different concentrations of the nucleoside to the proliferating T cell cultures performed as in A. C) Cultures were performed as in B. The percentage of CD4+FOXP3high cells respect to the total CD4+ cells was represented as Treg frequency. Live cells were expressed as the percentage of the Ghost Dye™ Red 780 unstained T CD4+ cells with respect to the total CD4+ cells. n ≥ 4 in all experiments. The results are presented as the means ± SD. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

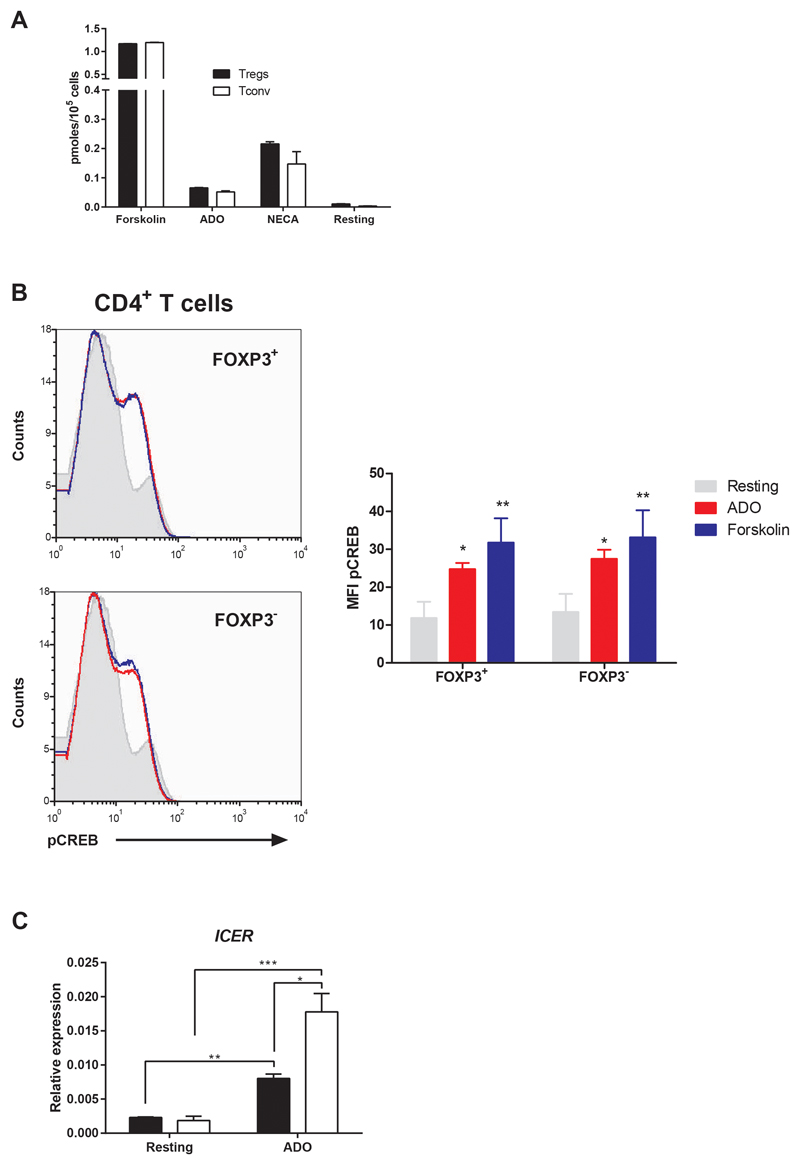

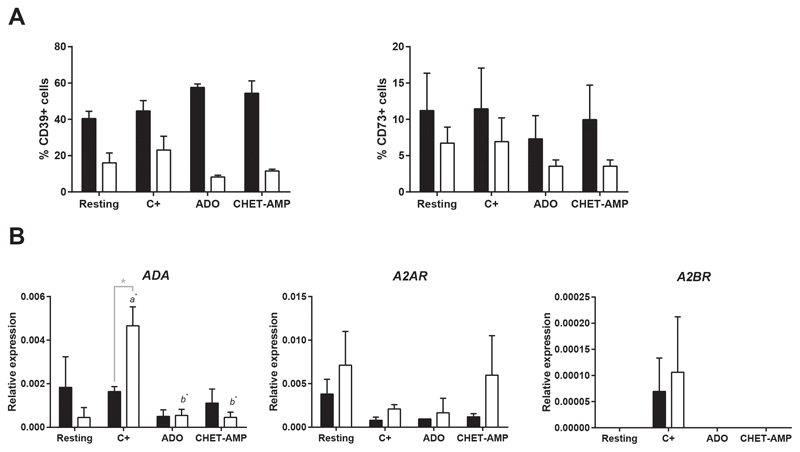

3.3. ADO activates cAMP signaling but does not change the expression of the CD39-CD73-A2R axis in human T cells

ADO-dependent A2 receptor activation and the subsequent cAMP increase in T cells have been previously described (4). To compare this activation between human Tregs and Teffs, we incubated isolated human Tregs or CD4+CD25-Tconv in the presence of ADO, and we observed an increase in the production of intracellular cAMP (Figure 3A), similar to that obtained in the presence of the adenosine receptor agonist NECA. Nevertheless, no differences were observed between both T cell populations. Similar results were obtained for the cAMP signaling pathway down-stream transcription factor cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB); the phosphorylation of serine 133 was the same for Tregs and Teffs (Figure 3B). However, when we analyzed the expression of ICER, we observed a significant increase in Tconv after 48 h of incubation with ADO whereas this increase was less marked for Tregs (Figure 3C). On the other hand, we examined the effect of eADO on the CD39-CD73-A2R axis in human T cells. The expression of CD39 and CD73, in both Tregs and Teffs, did not significantly change when eADO or CHET-AMP were present in total T cell proliferation culture, as analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 4A). The remaining components of the axis were analyzed by genetic expression due to the absence of working antibodies. To this end, Tregs and Tconv were isolated and cultured separately. The same rate of inhibition of the proliferation was observed for any extracellular nucleotide added as for total T cells (Figure S3A). In this case, the expression of ADA was increased significantly after CD3/CD28 activation in Tconv but not in Tregs. eADO and even CHET-AMP were able to dampen this increase (Figure 4B). However, the levels of CD26, a surface-bound glycoprotein associated with plasma membrane ADA, did not significantly change in any case (Figure S3B). However, A2 receptors did not show any significant change, although we could observe the overexpression of A2BR after activation in both T cell populations with respect to resting and eADO or CHET-AMP conditions (Figure 4B). Nevertheless, the maximum level of A2BR expression in T cells was 10 to 20-fold lower than A2AR expression (Figure S3C).

Figure 3. Effect of ADO in the cAMP signaling pathway in human CD4+ T cells.

A) Intracellular cAMP concentration in isolated Tregs and Tconv activated with 10 μM Forskolin, 30 μM ADO and 10 μM NECA or rested for 30 min. B) Histogram representing the MFI of phosphorylated CREB as measured by flow cytometry in isolated CD4+ T cells after its activation with 30 μM ADO or 10 μM forskolin. CD4+ T cells were obtained by density centrifugation of whole blood previously incubated with the RosetteSep Human CD4 T Cell Enrichment Cocktail (StemCell Technologies). C) Effect of ADO in the relative expression of ICER in isolated Tregs (black bar) or Tconv (white bar) as determined by qPCR. Cells were incubated in presence of 30 μM ADO during 48 h without CD3/CD28 engagement. n ≥ 4 in all experiments. The results are presented as the means ± SD. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

Figure 4. Effect of ADO signaling in the CD39-CD73-A2R axis.

A) Percentage of CD4+CD25highTregs (black bars) and Teff (white bars) that express membrane CD39 and CD73 as determined by flow cytometry. B) Relative expression of ADA, A2AR and A2BR in isolated Tregs (black bars) and Tconv (white bars) as determined by qPCR. Isolated T cells were processed directly (Resting) or proliferated by CD3/CD28 engagement for 4 days in the absence (C+) or presence of 30 μM ADO or 100 μM CHET-AMP before analysis. n ≥ 4 in all experiments. The results are presented as the means ± SD. a represents statistically significant differences between the C+ and resting sample, while b represents statistically significant differences compared to the C+. *p ≤ 0.05.

3.4. ADO inhibition of human T cell activation is reversible but does not affect nTregs suppressor capacity

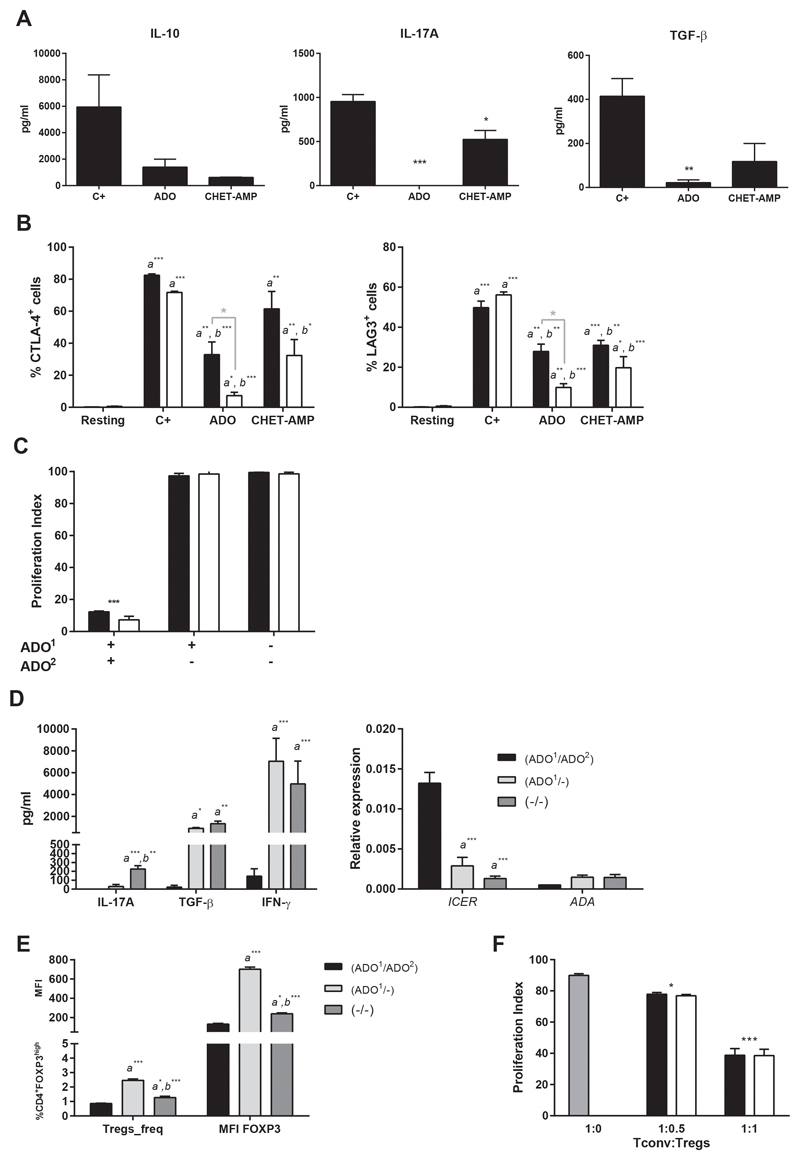

We examined whether eADO signaling would affect the release of principal cytokines involved in Tregs function. As shown in Figure 5A, IL-10, IL-17A and TGF-β secretion was decreased in the presence of eADO or CHET-AMP after total T cell activation, even when both T cell populations were incubated separately (Figure S4A). The same effect was observed when we analyzed the T cell activation markers CTLA-4 and LAG-3. Activated T cells increased the membrane expression of both proteins, whereas eADO or even CHET-AMP moderated this increase (Figure 5B). Nevertheless, the decrease in CTLA-4 and LAG-3 was markedly higher in Teffs than in Tregs. However, when we removed eADO from the culture, T cells recovered its proliferation capacity (Figure 5C), and IFN-γ and TGF-β production, besides a low release of IL-17A (Figure 5D). Moreover, expression of ICER induced by ADO decreased after eADO removal, whereas ADA expression slightly increased when eADO was withdrawn (Figure 5D). Likewise, when eADO was removed, we found a higher frequency of FOXP3highTregs with a higher FOXP3 expression (Figure 5E) when compared with those cultures in absence of eADO (Figure 5E).

Figure 5. Effect of ADO in T cells functionality.

A) Secreted IL-10, IL-17A and TGF-β cytokines from total T cell cultures. B) Percentage of CD4+FOXP3highTregs (black bars) and Teffs (white bars) that express membrane CTLA-4 or LAG-3 as determined by flow cytometry. C) Proliferation index of Tregs (black bars) and Teffs (white bars) cultured in a double-round fashion as explained in Material and Methods. Cells were CFSE-stained after the first round of culture. ADO1 indicate the addition of 30 μM of ADO in the first round of culture and ADO2 indicated the addition of the same amount of ADO in the second round of culture. D) Secreted IL-17A, TGF-β and IFN-γ and relative expression of ICER and ADA from total T cells after a double-round culture performed as in Figure 5C. E) Percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing FOXP3high (Treg_freq) and MFI of FOXP3 on those Tregs from total T cells after a double-round culture performed as in C. a represents statistically significant differences compared with ADO1/ADO2 stimulation whereas b represents statistically significant differences compared with ADO1/- stimulation. F) Tregs suppressor capacity was analyzed by the decrease of the proliferation index of Tconv. 50 x 103 CFSE stained Tconv were activated by anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence of increased amounts of isogeneic Tregs previously incubated with (white bars) or without (black bars) 30 μM ADO for 24 h. Gray bar represents the positive control proliferation of Tconv in the absence of Tregs. X-axis represents the Tconv:Tregs ratio. n ≥ 4 in all experiments. The results are presented as the means ± SD. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

On the other hand, when we studied the suppressor ability of nTregs, we observed that eADO had no effect, such as 24h eADO-stimulated nTregs were able to inhibit the proliferation of isogeneic Tconv at the same level as control nTregs (Figure 5F).

3.5. Tolerant liver transplant patients present differences in ADA expression compared to non-tolerant patients along an IS withdrawal process

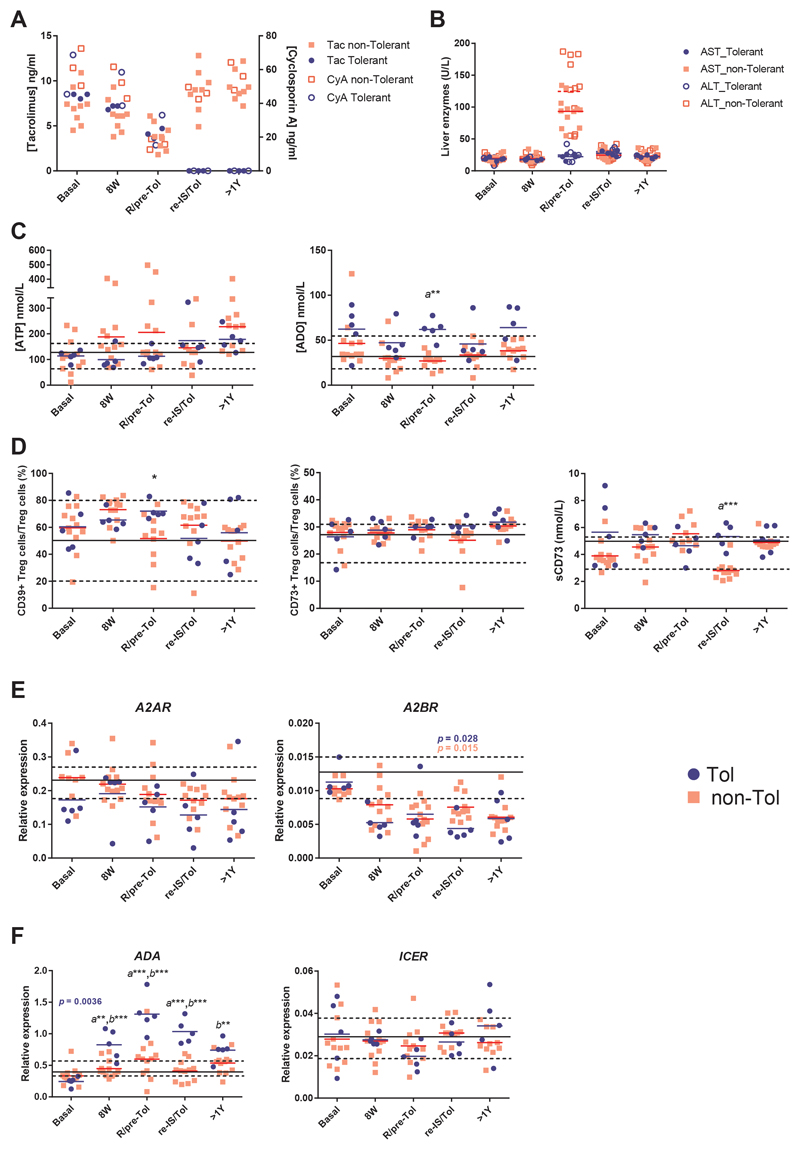

To determine the influence of ADO signaling through the activation of theCD39-CD73-A2R axis in the induction of clinical tolerance after liver transplantation, 17 LT patients were subjected to IS withdrawal (see Table 1 and Supporting information for demographic characteristics). Likewise, 12 healthy volunteers were analyzed. Five LT patients became tolerant (Tol; 3 male, 2 female), while the other 12 patients experienced a rejection episode and were grouped as non-tolerant patients (non-Tol; 9 male, 3 female). Five prospective samples from each LT patient were selected (see Supporting Information) based on the blood IS and liver enzymes concentration (Figures 6 A-B). Basal IS was decreasing in parallel and in a gradual form for both groups of patients in the first 3 selected time-points. At the moment of rejection, the 12 patients presented a mean of IS reduction of 53.53 ± 4.83 % (Figure 6A), whereas liver enzymes increased up to 93.21 ± 6.85 and 124.7 ± 15.83 U/L, for AST and ALT, respectively (Figure 6B). Selected samples for Tol patients at this time-point (pre-Tol) showed no significant differences in IS reduction (55.30 ± 4.71 %; p = 0.83) (Figure 6A), whereas liver enzymes remained under normal values (22.25 ± 2.01 and 24.75 ± 5.23 U/L, respectively. ***p < 0.0001) (Figure 6b). When the plasma concentrations of ATP or ADO were analyzed, ATP was slightly higher in non-Tol patients from the beginning of IS withdrawal until rejection, compared with Tol group (Figure 6C). However, the plasma ADO concentration was higher in the Tol group with respect to the non-Tol group, reaching a significant difference in the R/pre-Tol sample (Figure 6C). Both parameters presented a slight but significant negative correlation (r = -0.364; **p = 0.004) (Figure S5A). Similarly, we found significant differences between both groups in the axis CD39-CD73-A2R during the IS withdrawal follow-up, principally at the R/pre-Tol and re-IS/Tol samples (Figures 6D-E). Tol patients had a higher frequency of CD39+ Tregs than non-Tol patients at the R/pre-Tol time-point (Figure 6D), whereas CD73 expression remained unaltered. Although CD73 is weakly present in the plasma membrane of human Tregs, these cells possess high levels of intracellular CD73 and therefore have the potential to up-regulate surface ectonucleotidase activity in the appropriate circumstances or to secrete sCD73 to the extracellular medium(9). So, we analyzed the presence of soluble CD73 (sCD73) in the plasma of the patients, and we observed a higher concentration in the Tol group at the re-IS/Tol time-point (Figure 6D). Additionally, sCD73 correlated positively with the CD73 MFI of Tregs (r = 0.553; ***p ≤ 0.001) (Figure S5B). However, neither A2AR nor A2BR expression presented significant differences between both groups of patients, although A2BR expression decreased significantly along the process of IS withdrawal in both groups (Figure 6E). Likewise, we did not found differences when we activated the patient PBMCs in the presence or absence of 30 μM ATP and analyzed the inhibition of the proliferation between both groups of patients. (Figure S5C). Strikingly, the higher changes were observed in the relative ADA gene expression. The evolution of this expression clearly changed with time in Tol patients (p = 0.0036) and was much higher in Tol patients with respect to the non-Tol group from 8W until the re-IS/Tol sample, showing significant differences between both groups (Figure 6F). Moreover, ADA expression in Tol patients was also significantly different compared with the healthy volunteers at the same time-points (Figure 6F). CD26 did not follow the same evolution as ADA expression, although a weak positive correlation between ADA expression and the MFI of CD26 in Teffs was observed (r = 0.298; p = 0.019) (Figure S5D). Similarly, relative ICER expression did not change between groups (Figure 5F), but we could observe a negative correlation (r = -0.554; p = 0.032) with ADA expression into the Tol group when we analyzed the time-points from 8W until re-IS/Tol (Figure S5E), just when ADA experimented significantly changes in its expression.

Figure 6. ADO signaling in tolerant liver transplant patients.

A-B) Plasma levels of cyclosporin A or Tacrolimus (A) and the principal liver enzymes AST or ALT (B) in the IS withdrawal follow-up for the 17 studied patients. C) Plasma levels of ADO and ATP expressed in nM as determined by UPLC-MS-UV or bioluminescence, respectively. D) The percentage of Tregs (CD4+CD25highCD127low/-) that express CD39 or CD73 as determined by flow cytometry from PBMCs and plasma levels of sCD73 as measured by ELISA (Deltaclon). E-F) The relative expression of A2AR, A2BR, ADA and ICER as determined by qPCR from stabilized whole blood. A significant p value in the evolution of ADA and A2BR relative expression as calculated by Friedman test is represented in blue for the Tol group and red for the non-Tol patients. Significant differences among groups in each time-point were calculated by using two-way ANOVA for matched values with Bonferroni's post-test. Mean (solid line) and 25-75 % percentile (dotted lines) from 12 healthy volunteers was plotted for each variable. a represents statistically significant differences between the Tol and non-Tol group, while b represents statistically significant differences compared to the healthy group. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001.

4. Discussion

The concept of artificially induce a state of operational tolerance in solid organ transplantation is gaining strength. Clinical trials injecting in vitro expanded Tregs or replacing classical immunosuppressive drugs by rapamycin derivatives, based on the differential effect exerted by rapamycin over human Tregs and Teffs, are some examples (24). Similarly, a differential role of eADO signaling for Tregs and Teffs has been proposed: inhibiting Teffs activity and inducing or enhancing Tregs activity (12). However, these data have been based on murine experiments, whereas only a differential role for extracellular nucleotides metabolism between human Tregs and non-Tregs has been proposed in the context of HIV infection (25).

Thereby, we examined the capacity of extracellular nucleotides to impair the proliferation and the activity of human Teffs whereas improve Treg capacities, similar to murine cells. Our study show that relatively low concentrations of nucleotides and even ADO (IC50 ≈ 10 μM) inhibited T cell proliferation, similar to other published works (26). As expected, the inhibition of T cell proliferation was mediated by ADO after extracellular nucleotide degradation by the sequential action of CD39 and CD73. This eADO binds to A2R of T cells, evoking an increase in cAMP and activating cAMP downstream signaling. However, although ADO inhibited the proliferation of human Teffs as expected, the differential effect on Tregs did not follow the same pattern as established for mice. eADO inhibited both the proliferation and the activation of Tregs and Teffs with the same effectiveness, blocking the proliferation of Tregs, repressing the production of inhibitory cytokines such as TGF-β or IL-10 and down-regulating the expression of LAG-3 and CTLA-4, opposite to what happens in mice (13–15). An indirect cause of the inhibitory effects due to lack of IL-2 production by Tconv could be excluded, as addition of high concentrations of IL-2 to both total CD4+ or isolated Treg cells did not change the results. Whereas the stimulation of A2AR increased the number of mouse Tregs expressing CD39 and CD73 (15), ADO signaling does not appear to affect the CD39-CD73-A2R axis expression in human Tregs. Even though T cell activation is clearly inhibited by eADO, those do not become completely anergic T cells. When eADO was removed, T cells returned to be activated by TCR engagement. Interestingly, Treg activation returned stronger after removing eADO, with high expression of FOXP3, high TGF-β secretion and maintaining its suppressor capacity. It could be explained by the elevated expression of ICER in the presence of eADO. TGF-β-mediated conversion of responders to iTregs, occurs through CREB binding protein (CBP)/CREB-mediated transcription of FOXP3. However, if ICER is induced, it competes with CREB for DNA binding and may lead to uncoupling of a CBP-mediated TGF-β transcriptional response (18). Nevertheless, after eliminating the eADO, and so the induction of ICER, these cells are able to hugely express FOXP3.

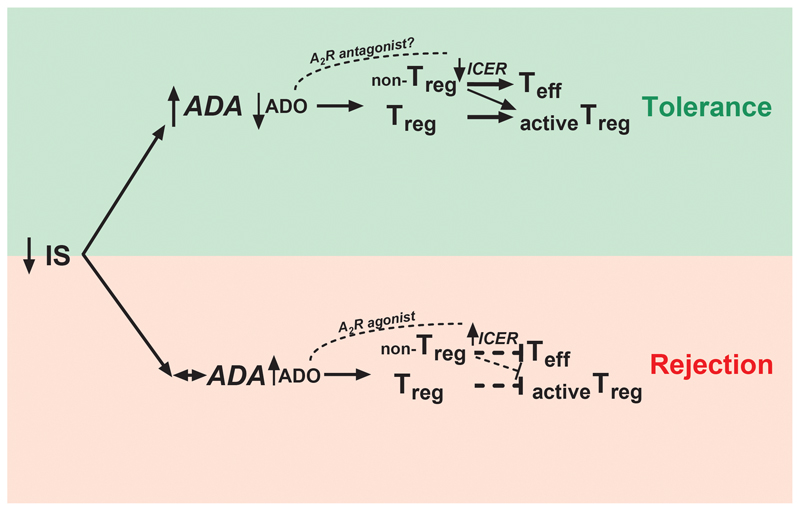

The modulation of the axis CD39-CD73-A2R is a hot topic in the field of transplantation and tolerance (27). However, we found no or slight differences both in the expression of the axis CD39-CD73-A2R and even in the anti-proliferative action of extracellular nucleotides between patient groups. Only the percentage of CD39+ Tregs and the plasmatic levels of soluble CD73 reached statistically significant differences between patient groups, although not with healthy volunteers, at the time-point when both groups separated into the Tol and non-Tol groups, and typically disappear with time. This phenomenon was previously found for mRNA FOXP3 expression (28), although we cannot discard that those differences are both as a result of the rejection process or due to a difference in the IS levels, at R/pre-Tol or re-IS/Tol time-points, respectively. Likewise, the differences in CD39+ Tregs could be attributable to cells migrating into the graft. Recently, Durant et al (29) have reported that the ability of memory Tregs from kidney transplant tolerant patients to degrade extracellular ATP was higher when compared with immunosuppressed patients with stable graft function. This ability correlated with a higher expression of CD39 by these memory Tregs (30). Even though liver and kidney tolerant patients exhibited distinct transcriptional and cell-phenotypic patterns (31), a future analysis of the expression of CD39 among different Treg subsets in Tol LT patients would be of great interest. Strikingly, only ADA mRNA expression presented significant differences in the evolution along the IS withdrawal in Tol patients, whereas its expression remained unaltered in the non-Tol group. Moreover, the differences began to be noticeable before the rejection episode, and were significantly different respect to healthy samples, which confers to ADA expression a great value as a new tolerance biomarker. ADA is ubiquitously expressed and functions as part of the purine salvage pathway. In certain cell types, is also complexed with CD26 on the cell surface. ADA catalyzes the deamination of adenosine, forming inosine. ADA deficiency evokes an accumulation of ADO which may mediate a defective TCR activation in vivo, leading to severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) (32). At similar levels of IS, non-Tol patients are not able to induce the expression of ADA, which would entail a lower degradation of ADO, enabling its accumulation (Figure 7). However, we did not see accumulation of plasmatic ADO in non-Tol patients. Nevertheless, the levels of plasma ADO were in the range of nM (Figure 6C), similar to those previously published (33), whereas IC50 for eADO in the in vitro experiments was about 10 μM. This difference could be due to the extracellular nucleotide concentration reached in the proximity of the plasma membrane surface, where they bind their receptors, which can be up to 20-fold higher than those measured in the bulk medium (34, 35). Curiously, Tregs from ADA deficient-SCID patients were reduced in number and showed decreased suppressive activity, which were corrected after gene therapy (36). In Tol patients, overexpression of ADA would favor the activation of Tregs (Figure 7). It could also be related with the decrease of ICER after eADO degradation, allowing the induction of new Tregs coming from non-Tregs (18) (Figure 7). Although does not exist a complete correlation between ADA and ICER evolution in the prospective study, it is worth noting that patient samples were extracted from complete blood, whereas in vitro experiments were carried out in isolated T cells. Further studies to determine the exact cells which modulate this expression after IS withdrawal will be necessary. Moreover, these findings are consistent with the idea that tolerance needs an active and well-functioning immune systemduring the process (37).

Figure 7. Schematic diagram linking the in vitro data to functional tolerogenic results in the patients.

Increase of ADA expression after IS withdrawal distinguished Tol from non-Tol patients. ADA increase could be related with a higher degradation of ADO and therefore a down-regulation of ICER, evoking stronger activation of Tregs and promoting tolerance.

In theory, the ability of A2AR agonists to promote T cell tolerance in mice suggests that such agents could be used in transplantation, promoting long-term, peripheral tolerance in the absence of continued IS (13). However, paradoxically, and considering the present data, the use of these agonists in human transplantation point to be harmful because they mimic a rejection scenario (Figure 7). Nevertheless, the use of A2R antagonists could be considered as beneficial in the search for a state of operational tolerance (Figure 7).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from Fundación Mutua Madrileña (FMM13) for A.B-M., Instituto de Salud Carlos III- Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (PI12/02042) for J.A.P. and Instituto de Salud Carlos III–Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (PI13/00174), Sysmex, Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (SAF2017-88276-R) and the European Research Council (ERC-2013-CoG 614578) for P.P. as Principal Investigators.

We want to acknowledge the patients and healthy volunteers enrolled in this study and the BioBank "Biobanco en Red de la Región de Murcia" (PT13/0010/0018) integrated in the Spanish National Biobanks Network (B.000859) for its collaboration.

Abbreviations

- CHET-AMP

2-(cyclohexylethylthio)-AMP

- ADO

adenosine

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- ADA

adenosine deaminase

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- A2R

adenosine A2 receptor

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- CFSE

carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- cAMP

cyclic AMP

- CRE

cAMP response element

- Tconv

conventional T cells

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4

- NTPDase1, ENTPD1,CD39

ecto-nucleotide triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1

- CD73

ecto-5’-nucleotidase

- Teffs

effector T cells

- eADO

extracellular adenosine

- FOXP3

Forkhead box P3

- IS

immunosuppression

- ICER

inducible cAMP early represor

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- LT

liver transplant

- LAG-3

lymphocyte-activation gene 3

- non-Tol

non-tolerant patients

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- sCD73

soluble CD73

- Tol

tolerant patients

- TGF-β

tumor growth factor β

Footnotes

ORCIDs: A.B-M. (0000-0001-5212-5006); L.M-A. (0000-0001-7497-6709); J.I.H. (0000-0001-5416-3073); A.E-T. (0000-0003-4922-1456); C.E.M. (0000-0002-0013-6624); P.A. (0000-0002-8152-3545); P.P. (0000-0002-9688-1804); J.A.P. (0000-0001-5017-7240).

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Sanchez-Fueyo A, Strom TB. Immunologic basis of graft rejection and tolerance following transplantation of liver or other solid organs. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(1):51–64. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pons JA, Revilla-Nuin B, Baroja-Mazo A, Ramírez P, Parrilla P. Experimental Organ Transplantation. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2013. Regulatory T cells in Transplantation; pp. 389–420. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salcido-Ochoa F, Tsang J, Tam P, Falk K, Rotzschke O. Regulatory T cells in transplantation: does extracellular adenosine triphosphate metabolism through CD39 play a crucial role? Transplantation Reviews. 2010;24(2):52–66. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cekic C, Linden J. Purinergic regulation of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16(3):177–192. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amores-Iniesta J, Barbera-Cremades M, Martinez CM, Pons JA, Revilla-Nuin B, Martinez-Alarcon L, et al. Extracellular ATP Activates the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Is an Early Danger Signal of Skin Allograft Rejection. Cell Rep. 2017;21(12):3414–3426. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vergani A, Fotino C, D'Addio F, Tezza S, Podetta M, Gatti F, et al. Effect of the purinergic inhibitor oxidized ATP in a model of islet allograft rejection. Diabetes. 2013;62(5):1665–1675. doi: 10.2337/db12-0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vergani A, Tezza S, D'Addio F, Fotino C, Liu K, Niewczas M, et al. Long-term heart transplant survival by targeting the ionotropic purinergic receptor P2X7. Circulation. 2013;127(4):463–475. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.123653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, Friedman D, Usheva A, Erat A, et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204(6):1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandapathil M, Hilldorfer B, Szczepanski MJ, Czystowska M, Szajnik M, Ren J, et al. Generation and accumulation of immunosuppressive adenosine by human CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(10):7176–7186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnstock G, Boeynaems J-M. Purinergic signalling and immune cells. Purinergic Signalling. 2014;10(4):529–564. doi: 10.1007/s11302-014-9427-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaji W, Tanaka S, Tsukimoto M, Kojima S. Adenosine A(2B) receptor antagonist PSB603 suppresses tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting induction of regulatory T cells. J Toxicol Sci. 2014;39(2):191–198. doi: 10.2131/jts.39.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Extracellular Adenosine-Mediated Modulation of Regulatory T Cells. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zarek PE, Huang CT, Lutz ER, Kowalski J, Horton MR, Linden J, et al. A2A receptor signaling promotes peripheral tolerance by inducing T-cell anergy and the generation of adaptive regulatory T cells. Blood. 2008;111(1):251–259. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sevigny CP, Li L, Awad AS, Huang L, McDuffie M, Linden J, et al. Activation of Adenosine 2A Receptors Attenuates Allograft Rejection and Alloantigen Recognition. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;178(7):4240–4249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohta A, Kini R, Ohta A, Subramanian M, Madasu M, Sitkovsky M. The development and immunosuppressive functions of CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are under influence of the adenosine-A2A adenosine receptor pathway. Frontiers in Immunology. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bopp T, Becker C, Klein M, Klein-Hessling S, Palmetshofer A, Serfling E, et al. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate is a key component of regulatory T cell mediated suppression. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204(6):1303–1310. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sitkovsky MV. T regulatory cells: hypoxia-adenosinergic suppression and re-direction of the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(3):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodor J, Fehervari Z, Diamond B, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cell-mediated suppression: potential role of ICER. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2006;81(1):161–167. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0706474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de la Garza RG, Sarobe P, Merino J, Lasarte JJ, D'Avola D, Belsue V, et al. Trial of complete weaning from immunosuppression for liver transplant recipients: factors predictive of tolerance. Liver Transpl. 2013;19(9):937–944. doi: 10.1002/lt.23686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revilla-Nuin B, de Bejar A, Martinez-Alarcon L, Herrero JI, Martinez-Caceres CM, Ramirez P, et al. Differential profile of activated regulatory T cell subsets and microRNAs in tolerant liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2017;23(7):933–945. doi: 10.1002/lt.24691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Tayeb A, Iqbal J, Behrenswerth A, Romio M, Schneider M, Zimmermann H, et al. Nucleoside-5'-monophosphates as prodrugs of adenosine A2A receptor agonists activated by ecto-5'-nucleotidase. J Med Chem. 2009;52(23):7669–7677. doi: 10.1021/jm900538v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flogel U, Burghoff S, van Lent PLEM, Temme S, Galbarz L, Ding Z, et al. Selective Activation of Adenosine A2A Receptors on Immune Cells by a CD73-Dependent Prodrug Suppresses Joint Inflammation in Experimental Rheumatoid Arthritis. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(146):146ra108–146ra108. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Voort EI, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. Transient expression of FOXP3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(1):129–138. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baroja-Mazo A, Revilla-Nuin B, Parrilla P, Martinez-Alarcon L, Ramirez P, Pons JA. Tolerance in liver transplantation: Biomarkers and clinical relevance. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(34):7676–7691. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i34.7676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Abente J, Correa-Rocha R, Pion M. Functional Mechanisms of Treg in the Context of HIV Infection and the Janus Face of Immune Suppression. Front Immunol. 2016;7:192. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hesdorffer CS, Malchinkhuu E, Biragyn A, Mabrouk OS, Kennedy RT, Madara K, et al. Distinctive immunoregulatory effects of adenosine on T cells of older humans. The FASEB Journal. 2011;26(3):1301–1310. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-197046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castillo-Leon E, Dellepiane S, Fiorina P. ATP and T-cell-mediated rejection. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2018;23(1):34–43. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pons JA, Revilla-Nuin B, Baroja-Mazo A, Ramírez P, Martínez-Alarcón L, Sánchez-Bueno F, et al. FoxP3 in Peripheral Blood Is Associated With Operational Tolerance in Liver Transplant Patients During Immunosuppression Withdrawal. Transplantation. 2008;86(10):1370–1378. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318188d3e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Durand M, Dubois F, Dejou C, Durand E, Danger R, Chesneau M, et al. Increased degradation of ATP is driven by memory regulatory T cells in kidney transplantation tolerance. Kidney Int. 2018;93(5):1154–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braza F, Dugast E, Panov I, Paul C, Vogt K, Pallier A, et al. Central Role of CD45RA- Foxp3hi Memory Regulatory T Cells in Clinical Kidney Transplantation Tolerance. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(8):1795–1805. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lozano JJ, Pallier A, Martinez-Llordella M, Danger R, Lopez M, Giral M, et al. Comparison of transcriptional and blood cell-phenotypic markers between operationally tolerant liver and kidney recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(9):1916–1926. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitmore KV, Gaspar HB. Adenosine Deaminase Deficiency – More Than Just an Immunodeficiency. Frontiers in Immunology. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorman MW, Feigl EO, Buffington CW. Human Plasma ATP Concentration. Clinical Chemistry. 2006;53(2):318–325. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.076364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beigi R, Kobatake E, Aizawa M, Dubyak GR. Detection of local ATP release from activated platelets using cell surface-attached firefly luciferase. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(1 Pt 1):C267–278. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.1.C267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pellegatti P, Falzoni S, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Di Virgilio F. A novel recombinant plasma membrane-targeted luciferase reveals a new pathway for ATP secretion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(8):3659–3665. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sauer AV, Brigida I, Carriglio N, Hernandez RJ, Scaramuzza S, Clavenna D, et al. Alterations in the adenosine metabolism and CD39/CD73 adenosinergic machinery cause loss of Treg cell function and autoimmunity in ADA-deficient SCID. Blood. 2012;119(6):1428–1439. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-366781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop GA, McCaughan GW. Immune activation is required for the induction of liver allograft tolerance: Implications for immunosuppressive therapy. Liver Transplantation. 2001;7(3):161–172. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.22321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.