Abstract

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM), also referred to as mediastinal emphysema, is defined as the presence of free air in the mediastinal cavity without a clear and identifiable cause. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, in general, is a relatively rare condition, more so in the setting of pregnancy or labor. Clinically, SPM may present as dyspnea, chest pain, and subcutaneous swelling, which may be of serious concern in the setting of pregnancy. A comprehensive literature review revealed that the majority of patients are primiparas, of a younger age, and have term or longer durations of pregnancy. The second stage of labor was found to be most commonly associated with the development of SPM. The pathomechanism suggests that performing the Valsalva maneuver during the active stages of labor may play a role in the development of SPM. Once diagnosed, patients with SPM in pregnancy are admitted to the hospital, treated conservatively, and followed until resolution. SPM must be diagnosed and managed promptly due to rare but serious complications. In addition, dyspnea or chest pain with an unknown etiology should include SPM in the differential diagnosis, especially in the setting of pregnancy and labor.

Keywords: spontaneous pneumomediastinum, pneumomediastinum, pregnancy, labor, subcutaneous emphysema, dyspnea, chest pain

Introduction and background

Introduction

Pneumomediastinum (PM) is defined as the presence of free air in the mediastinal cavity, which was originally described by Laënnec in 1819 [1]. Pneumomediastinum is most commonly seen secondary to a known cause, such as blunt force trauma or iatrogenic in nature (i.e. endoscopic procedures or central line placement). However, PM without a clearly defined etiology is termed spontaneous pneumomediastinum (SPM). SPM, though with the moniker “spontaneous,” may occur due to various physiologic or pathologic processes. It is most often seen in the setting of underlying pulmonary conditions, such as asthma, interstitial lung disease, or chronic tobacco use [2]. A physiologic process in which SPM may occur is in the setting of pregnancy, labor, and delivery. Though it is a rare occurrence, it may indicate other, possible, serious underlying pathologies. Its clinical presentation is also often confused with that of other chronic pulmonary conditions and may remain undiagnosed. Herein, the authors attempt to summarize the entity of SPM in the setting of pregnancy through a case and literature review. The goal is to form an awareness of the clinical presentation and course of SPM in pregnancy. The findings of our comprehensive review are presented along with a review of the literature outlining the clinical presentation, diagnostic algorithm, as well as the therapeutic process in the setting of SPM.

Methods

A search was conducted of the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE/PubMed databases, with the objective of identifying all articles published in the English language between January 1980 and May 2018 with “spontaneous pneumomediastinum” or “mediastinal emphysema” in conjunction with “pregnancy” or “labor.” Combinations of medical subject heading terms associated with spontaneous pneumomediastinum in pregnancy or labor were also searched, including “postpartum pneumomediastinum,” “peripartum pneumomediastinum,” and “obstetric mediastinal emphysema.” We mainly selected publications that were recently published but did not exclude any relevant older manuscripts. We also searched the reference lists of all articles identified by this search strategy and selected those judged to be relevant. All pertinent literature was retrieved, analyzed, and thoroughly searched in order to identify any potential additional manuscripts that could be referenced. All data were accessed between January and June 2017. Our comprehensive PubMed/MEDLINE search revealed a total of 184 manuscripts, of which duplicates, articles not of the English language, or not related to our focus were excluded. This yielded a total of 44 manuscripts that were completely assessed and incorporated into this review.

Review

Pregnancy and pneumomediastinum

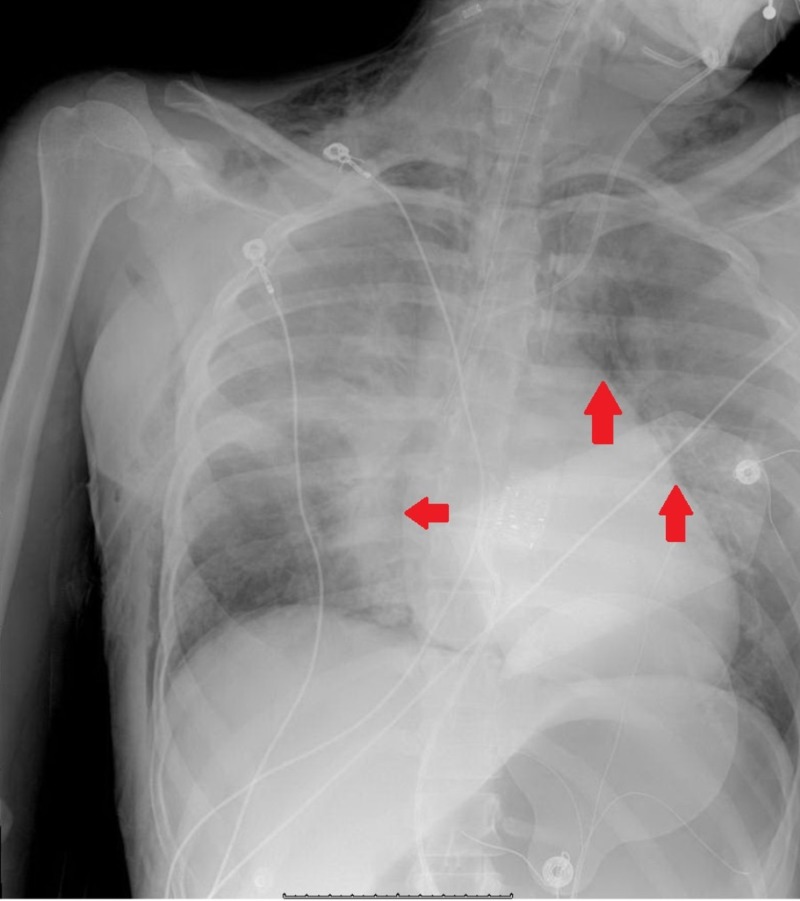

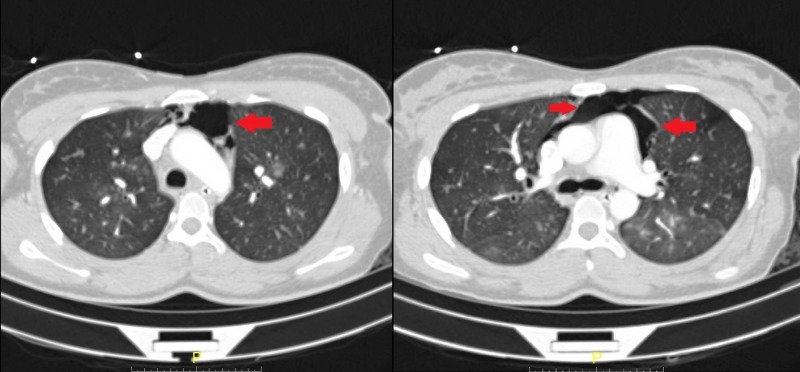

The mediastinal cavity is delineated laterally by the pleural cavities, inferiorly by the diaphragm, superiorly by the thoracic inlet, anteriorly by the sternum, and posteriorly by the thoracic vertebrae. The structures encompassed in the mediastinum are primarily cardiac in nature, including the heart, pericardium, as well as the great vessels. Pneumomediastinum refers to the presence of free air within the mediastinal cavity. SPM, initially described by Laennec in 1819, was further characterized in a case series by Hamman in 1939 [3]. Radiologic findings have been shown in Figures 1-2. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, in general, is a relatively rare condition with a reported incidence of less than 1:44,000 and in the setting of pregnancy or labor, approximately 1:100,000 [4-5]. Though many pre-existing medical conditions have been thought to predispose to the development of SPM, the pathophysiologic process is the same [2].

Figure 1. Chest X-ray showing the presence of pneumomediastinum.

Red arrows point to free air around the heart silhouette.

Figure 2. Computer tomography showing the presence of free air in the mediastinum anterior to the heart and great vessels.

Red arrows point to the pockets of free air in the mediastinal cavity.

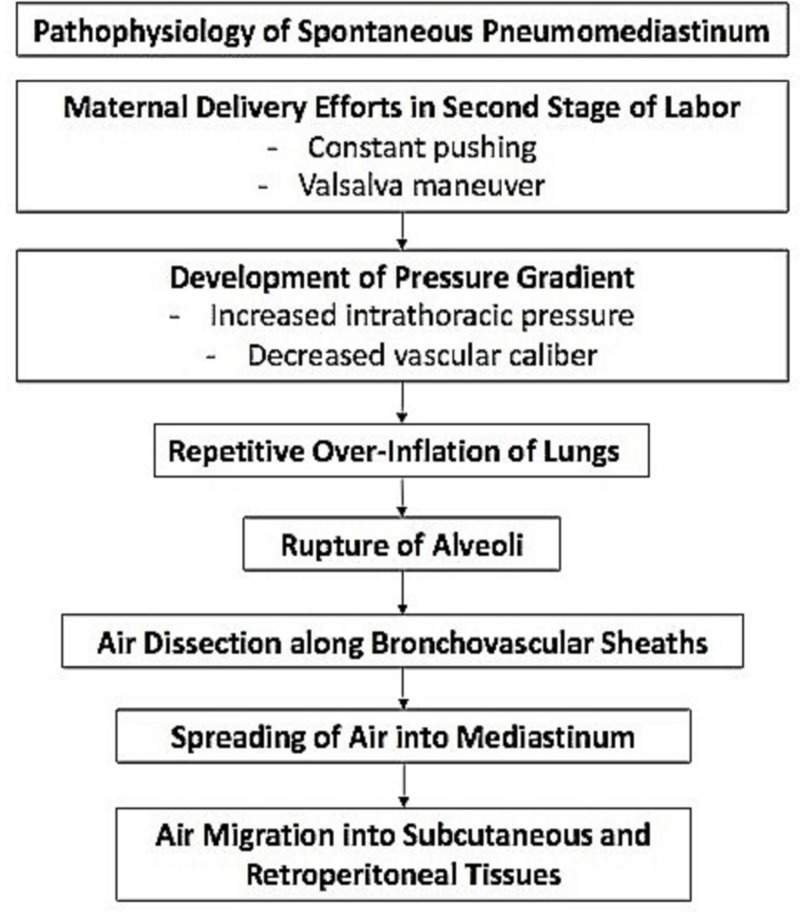

Theory has it that sudden changes in intrathoracic pressure may precede the development of SPM. The pathogenesis of SPM was first proposed by Macklin in 1939. His proposed mechanism was that alveolar ruptures lead to air dissection along bronchovascular sheaths with the eventual spreading of this inspired air into the mediastinum [6]. This was later coined the "Macklin Effect" in 1944, which broke down the formation of PM into a linear process beginning with alveolar ruptures, leading to air dissecting along bronchovascular sheaths and culminating with the spread of interstitial emphysema into the mediastinum [7]. In the setting of pregnancy, it has been theorized that the Valsalva maneuver produced associated with the second stage of labor may cause a rupture of the alveoli leading to this condition and the propagation of the Macklin effect.

There are four stages of labor. The first stage lasts from the onset of true labor to complete dilation of the cervix. The second stage spans from a complete dilation of the cervix to the birth of the baby. The third stage lasts from the birth of the baby to the delivery of the placenta. The fourth stage spans from the delivery of the placenta to the stabilization of the patient's condition, usually at about six hours postpartum [8]. SPM is most often seen in the second stage of labor and does not negatively affect the following pregnancies. This may due to the “pushing” and strain faced in this stage of labor.

Pathophysiology

As mentioned, the Valsalva maneuver has been implicated in the development of SPM. The Valsalva maneuver is a forced expiratory effort against a closed glottis, which results in a change in intrathoracic pressure, affecting venous return, cardiac output, arterial pressure, and heart rate. During Valsalva, the intrathoracic pressure becomes positive due to the compression of the thoracic organs. Of the various explanations for pneumomediastinum in pregnancy, the most widely accepted theory implicates the rupture of marginal pulmonary alveoli as a result of repetitive overinflation of the lungs and of high intra-alveolar pressures during the second stage of labor [9]. In maternal delivery efforts, constant pushing during labor consequently results in increased intrathoracic pressure in the presence of decreased vascular caliber; this establishes a pressure gradient in the vascular sheath, which allows air to dissect into the mediastinum. From the mediastinum, air migrates along the fascial planes into the subcutaneous and retroperitoneal tissues [10-11]. An outline of this process has been shown in Figure 3 [12].

Figure 3. The proposed pathophysiologic process of spontaneous pneumomediastinum in pregnancy.

In addition to the “pushing” associated with the delivery of the fetus, other physiological alterations of the respiratory system occur during the latter parts of pregnancy. These changes are mainly the consequence of the progestin stimulation of the respiratory drive and consist of a reduction in the functional residual capacity and an increase of about 70% in alveolar ventilation due to a breathing pattern with augmented respiratory rate and tidal volume. This may also contribute to the development of SPM [12]

Clinical characteristics

Our literary search methodology resulted in a total of 34 cases of pregnancy or labor-related spontaneous pneumomediastinum, which have been presented in Table 1 [5,13-41]. From our results, we have focused on certain patient characteristics, such as the duration of the pregnancy, parity, smoking history, as well as presenting signs and symptoms. SPM in pregnancy is typically seen in young patients; of the cases we have examined, the average age was 23.4 +/- 5.7 years of age. The majority of patients were nonsmokers without a previous history of asthma, showing that the diagnosis can be designated as “spontaneous” due to the unclear etiology.

Table 1. Summary of spontaneous pneumomediastinum cases in pregnancy.

| Author | Age | Parity | Stage of Labor | Duration of Labor (hours) | Duration of Pregnancy (weeks) | Treatment |

| Crean et al. 1981 [5] | 22 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 12 | N/A | Oxygen |

| Hubbert et al. 1981 [13] | 17 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | N/A | Oxygen, fentanyl, diazepam, & succinycholine |

| 18 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | N/A | Oxygen | |

| Karson et al. 1984 [14] | 20 y/o | 1st | 1st stage | N/A | 9 | Pyridoxine 2x daily |

| 20 y/o | 1st | 1st stage | N/A | 42 | None | |

| Jensen et al. 1987 [15] | 24 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 10.5 | 41 | Oxygen |

| Ramirez-Rivera et al. 1990 [16] | 15 y/o | 1ST | 2nd stage | 14 | N/A | Oxygen |

| Jayran-Nejad et al. 1993 [17] | 18 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 15.6 | 42 | Analgesia |

| Seidl et al. 1994 [18] | 23 y/o | 2nd | N/A | N/A | 42 | None |

| Gocmen et al. 1997 [19] | 17 y/o | 1st | N/A | 11 | 39 | Symptomatic management & monitoring |

| Shyamsunder et al. 1999 [20] | 18 y/o | 2nd | 2nd stage | N/A | 6 | None |

| Gorbach et al. 1997 [21] | 21 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | 4 | 9 | IV Fluids, Promethazine |

| Raley et al. 1997 [22] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 41 | Oxygen |

| Dhrampal et al. 2001 [23] | 36 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | 37 | Oxygen & analgesia |

| Sutherland et al. 2002 [24] | 32 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 8 | N/A | None |

| 22 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 13 | N/A | None | |

| Miguil et al. 2004 [25] | 19 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | 40 | Oxygen & analgesia |

| Balkan et al. 2006 [26] | 25 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | N/A | 36 | Oxygen |

| Bonin et al. 2006 [10] | 27 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 6 | 38 | Lorazepam for anxiety; anxiolytics for dyspnea |

| North et al. 2006 [27] | 32 y/o | N/A | 2nd | N/A | N/A | Laxatives |

| Yadav et al. 2008 [28] | 21 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 1.3 | N/A | Oxygen & analgesics |

| Mahboob et al. 2008 [9] | 24 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | 39 | Oral antibiotics |

| Zapardiel et al. 2009 [29] | 29 y/o | 1st | 4th stage – only time | 7 | 39 | Oxygen |

| Speksnijder et al. 2010 [30] | 15 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | 28 | Insulin, fluid, & potassium supplementation |

| Beynon et al. 2011 [31] | 18 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 4.3 | 39 + 2 | Antibiotics & analgesia |

| Wozniak et al. 2011 [32] | 20 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | 41 | Observation |

| Shrestha et al. 2011 [33] | 19 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | N/A | 36 | None |

| Kuruba et al. 2011 [34] | 32 y/o | 2nd | 2nd stage | 1.5 | 40 | None |

| McGregor et al. 2011 [35] | 27 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 1.5 | 40 | Oxygen & analgesia |

| Khoo et al. 2012 [36] | 33 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 12 | 40 | Analgesia & best rest |

| Kouki et al. 2013 [37] | 23 y/o | 1st | 2nd stage | 9 | 40 | Oxygen & analgesics and sedatives |

| Cho et al. 2015 [38] | 28 y/o | 1ST | 2nd stage | 5 | 36 | Oxygen & analgesics |

| Scala et al. 2016 [39] | 30 y/o | N/A | N/A | N/A | 40 | None |

| Nagarajan et al. 2017 [40] | 30 y/o | N/A | 2nd stage | N/A | 41 | Observation |

| Berdai et al. 2017 [41] | 22 y/o | 1ST | 2nd stage | 2H | 40 | Oxygen |

Parity

Parity was of interest in this patient population, as it has been reported that the second stage of labor is prolonged in a nulliparous woman as compared to a multiparous woman. In a study by Albers et al., it was found that the mean length of the second stage of labor in nulliparas was 54 minutes versus 18 minutes for multiparas [42]. Of the cases we have reviewed and the ones that have provided a parity status, it was found that 20/34 (58.8%) of cases were of women who were primiparas. It appears as if subsequent pregnancies are not as affected, as only 3/34 (8.8%) were observed to be in second pregnancies and beyond.

Pregnancy Duration and Delivery

As the majority of cases described are associated with pregnancy, the authors felt it necessary to analyze the duration of pregnancy among all cases. Cases that did not provide the duration of pregnancy or in the cases of early termination or fetal demise, duration of pregnancy was not considered. Of the cases that were reviewed, it was determined that the average length of pregnancy was 39.04 +/- 2.94 weeks. This is in line with previously reported works that reported that pregnancy-associated SPM most commonly occurs in the setting of full-term vaginal births [5]. Pregnancy-associated SPM is almost always seen in the setting of natural vaginal delivery, the pathophysiology of which has been discussed above. In very few cases, SPM in pregnancy has been seen in the first and fourth stages of labor, with 28 (80%) of cases occurring in the second stage of labor.

Signs and Symptoms

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, in general, presents with similar signs and symptoms among patients. The most commonly reported symptom is chest pain, followed by dyspnea [2]. Here, we focused on spontaneous pneumomediastinum presented during pregnancy. Of the cases that were reported, a summary of presenting clinical signs and symptoms has been shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Clinical signs and symptoms of pregnancy-associated SPM.

SPM: spontaneous pneumomediastinum

| Signs & Symptoms | Number of Cases (%) |

| Swelling & Subcutaneous Emphysema (face, neck, etc.) | 21 (60.0) |

| Dyspnea | 16 (45.7) |

| Chest Pain | 13 (37.1) |

| Crepitus | 10 (28.6) |

| Tachycardia | 7 (20.0) |

| Vomiting | 5 (14.3) |

| Cough | 3 (8.6) |

Although not in the situation of pregnant patients, SPM has been reported due to straining exercises, which also involve the Valsalva maneuver, and forceful coughing. It additionally has been reported in patients with a history of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and upper respiratory infection [2].

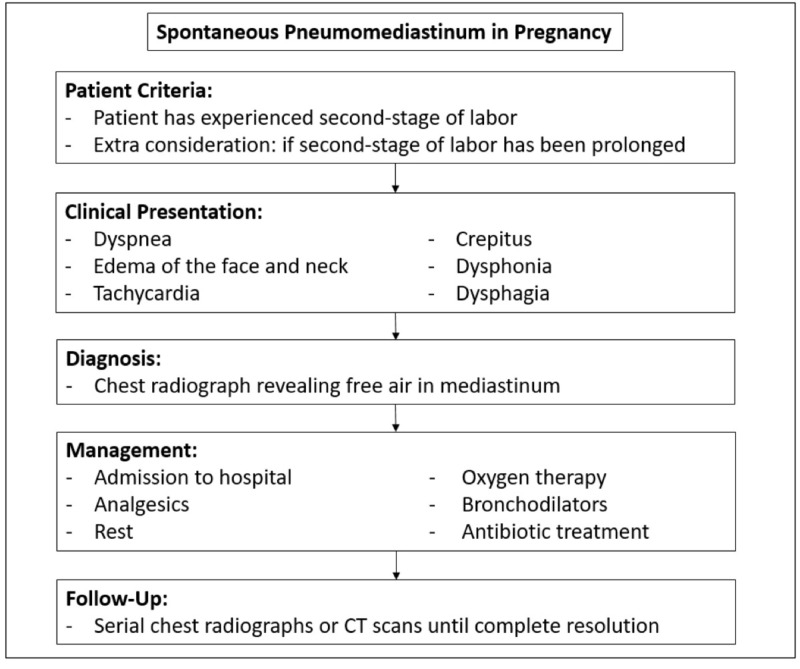

Management and complications

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum, in general, is not often included in the differential diagnosis and even more so in the setting of pregnancy due to its vague presentation. It is often treated as another causative factor of chest pain, dyspnea, and wheezing, such as asthma exacerbation. SPM usually follows a benign course and management is often conservative. The majority of patients admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of SPM are treated with analgesics, rest, oxygen therapy, bronchodilators, and occasionally antibiotic treatment [2,43]. If any pre-disposing condition (asthma, infection, airway obstruction, etc.) is responsive to pharmacological management, then SPM is self-limiting [2,44]. A diagnostic algorithm has been provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Diagnostic and management algorithm of SPM in pregnancy.

SPM: spontaneous pneumomediastinum

Complications of SPM are rare as the diagnosis is often expeditious due to an often overly ominous presentation. Timely management is important to avert any serious complications. If untreated or not monitored, SPM has shown a possibility to convert to tension or malignant PM, which may lead to a compression of the great vessels, ultimately having a deleterious effect on the fetus in the setting of pregnancy [7]. Mortality is extremely rare, as it is known that spontaneous pneumomediastinum typically resolves quickly by the free air being absorbed into the surrounding tissue. In the 34 cases we observed, there were no reports of complications and all cases were managed conservatively.

Conclusions

Spontaneous pneumomediastinum is a rare occurrence in the physiologic setting of pregnancy, labor, and delivery. It is thought the Valsalva maneuver produced in natural vaginal delivery and its physiologic consequences are the impetus for the development of SPM. A review of case reports in the literature revealed that a majority of patients are primiparas, of a younger age, and have term or longer durations of pregnancy. As the literature suggests, the second stage of labor is most commonly associated with the development of SPM. The cases reviewed are associated with the most common clinical signs and symptoms of SPM such as chest pain and dyspnea. Once diagnosed, patients should be admitted to the hospital, monitored, treated with analgesics, rest, and oxygen therapy until complete or near resolution. Once released from the hospital, patients may be followed with serial chest radiographs or CT scans until complete resolution. Physicians need to be aware of the possibility of SPM in parturient patients and include SPM in the differential, especially in the setting of dyspnea, chest pain, and relevant physical findings.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Rene Theophile Hyacinthe Laennec ( 1781-1826): the man behind the stethoscope. Roguin A. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:230–235. doi: 10.3121/cmr.4.3.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: time for consensus. Sahni S, Verma S, Grullon J, Esquire A, Patel P, Talwar A. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:460–464. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.117296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Hamman L. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1939;64:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, et al. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:1110–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in pregnancy. Case report. Crean PA, Stronge JM, FitzGerald MX. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981;88:952–954. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1981.tb02236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Transport of air along sheaths of pulmonic blood vessels from alveoli to mediastinum: clinical implications. Macklin CC. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 1939;64:913–926. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malignant interstitial emphysema of the lungs and mediastinum as an important occult complication in many respiratory diseases and other conditions: an interpretation of the clinical literature in the light of laboratory experiment. Macklin MM, Macklin CC. https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/Citation/1944/12000/Malignant_Interstitial_Emphysema_of_the_Lungs_and.1.aspx Medicine. 1944;23:281–358. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacker NF, Hobel CJ. Essentials of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2016. Normal labor, delivery, and postpartum care; pp. 96–125. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamman's syndrome: an atypical cause of postpartum chest pain. Mahboob A, Eckford SD. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:652–653. doi: 10.1080/01443610802378066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamman's syndrome (spontaneous pneumomediastinum) in a parturient: a case report [Article in English, French] Bonin MM. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28:128–131. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Postpartum pneumomediastinum (Hamman's syndrome) Majer S, Graber P. CMAJ. 2007;177:32. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pneumomediastinum: elucidation of the anatomic pathway by liquid ventilation. Jamadar DA, Kazerooni EA, Hirschl RB. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:309–311. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199603000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spontaneous tension pneumothorax and mediastinal emphysema associated with anesthesia for cesarean section. Hubbert CH, Roberson WT, Solomon JA. AANA J. 1981;49:59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pneumomediastinum in pregnancy: two case reports and a review of the literature, pathophysiology, and management. Karson EM, Saltzman D, Davis MR. https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/1984/09001/Pneumomediastinum_in_Pregnancy__Two_Case_Reports.10.aspx. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labor complicated by spontaneous emphysema. Jensen H, Asmussen I, Eliasen B. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66:567–568. doi: 10.3109/00016348709015738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Ramirez-Rivera J. Bol Asoc Med P R. 1990;82:359–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subcutaneous emphysema in labour. Jayran-Nejad Y. Anaesthesia. 1993;48:139–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1993.tb06853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema following vaginal delivery. Case report and review of the literature. Seidl JJ, Brotzman GL. http://go.galegroup.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA15828762&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=00943509&p=AONE&sw=w. J Fam Pract. 1994;39:178–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postpartum subcutaneous emphysema with pneumomediastinum. Göçmen A, Gül T, Sezer FA, Erden AC, Yilmaztürk A. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1997;119:86–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pneumomediastinum: the Valsalva crunch. Shyamsunder AK, Gyaw SM. Md Med J. 1999;48:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum secondary to hyperemesis gravidarum. Gorbach JS, Counselman FL, Mendelson MH. J Emerg Med. 1997;15:639–643. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(97)00142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum presenting as jaw pain during labor. Raley JC, Andrews JI. https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2001/11001/Spontaneous_Pneumomediastinum_Presenting_as_Jaw.4.aspx. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:904–906. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spontaneous cervical and mediastinal emphysema following childbirth. Dhrampal A, Jenkins J. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:93–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.01840-19.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pneumomediastinum during spontaneous vaginal delivery. Sutherland FW, Ho SY, Campanella C. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:314–315. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax associated with labour. Miguil M, Chekairi A. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13:117–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in 3rd trimester of pregnancy. Balkan ME, Alver G. http://www.atcs.jp/pdf/2006_12_5/362.pdf. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;12:362–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spontaneous cervical surgical emphysema and pneumomediastinum: a rare complication of childbirth. North CE, Candelier CK. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26:571–572. doi: 10.1080/01443610600821739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman's syndrome) in a labouring patient. Yadav Y, Ramesh L, Davies JA, Nawaz H, Wheeler R. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:651–652. doi: 10.1080/01443610802378058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pneumomediastinum during the fourth stage of labor. Zapardiel I, Delafuente-Valero J, Diaz-Miguel V, Godoy-Tundidor V, Bajo-Arenas JM. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2009;67:70–72. doi: 10.1159/000162103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a rare presentation of diabetic ketoacidosis in a pregnant woman. Speksnijder L, Duvekot JJ, Duschek EJ, Jebbink MC, Bremer HA. Obstet Med. 2010;3:158–160. doi: 10.1258/om.2010.100028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum following normal labour. Beynon F, Mearns S. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.07.2011.4556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Postpartum pneumomediastinum manifested by surgical emphysema. Should we always worry about underlying oesophageal rupture? Wozniak DR, Blackburn A. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.04.2011.4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Subcutaneous emphysema in pregnancy. Shrestha A, Acharya S. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2011;51:141–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Postpartum spontaneous pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema: Hamman's syndrome. Kuruba N, Hla TT. Obstet Med. 2011;4:127–128. doi: 10.1258/om.2011.110038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum during second stage of labour. McGregor A, Ogwu C, Uppal T, Wong MG. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.04.2011.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum with severe subcutaneous emphysema secondary to prolonged labor during normal vaginal delivery. Khoo J, Mahanta VR. Radiol Case Rep. 2012;7:713. doi: 10.2484/rcr.v7i3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Postpartum spontaneous pneumomediastinum 'Hamman's syndrome'. Kouki S, Fares AA. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-010354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum (Hamman's syndrome): a rare cause of postpartum chest pain. Cho C, Parratt JR, Smith S, Patel R. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-12-2010-3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in pregnancy: A case report. Scala R, Madioni C, Manta C, Maggiorelli C, Maccari U, Ciarleglio G. Rev Port Pneumol (Eng) 2016;22:129–131. doi: 10.1016/j.rppnen.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Intrapartum spontaneous pneumomediastinum and surgical emphysema (Hamman's syndrome) in a 30-year-old woman with asthma. Nagarajan DB, Ratwatte MD, Mathews J, Siddiqui M. BMJ Case Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-219223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum in labor. Berdai MA, Benlamkadem S, Labib S, Harandou M. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2017;2017:6235076. doi: 10.1155/2017/6235076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The duration of labor in healthy women. Albers LL. https://www.nature.com/articles/7200100. J Perinatol. 1999;19:114–119. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spontaneous pneumomediastinum. A report of 25 cases. Abolnik I, Lossos IS, Breuer R. Chest. 1991;100:93–95. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema of the head, neck, and mediastinum. Steffey WR, Cohn AM. Arch Otolaryngol. 1974;100:32–35. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1974.00780040036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]