Abstract

Background

This review aimed at examining the prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals in Western countries. Furthermore, possible occupational risk factors were analyzed.

Methods

The literature search was conducted from June to July 2016, with an update in December 2017 using the databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, LIVIVO, Science Direct, PubMed, and Web of Science. The quality assessment was performed with a standardized instrument consisting of 10 items. A meta-analysis was carried out to compute pooled prevalence rates for musculoskeletal diseases and pain.

Results

A total of 41 studies were included in this review; 30 studies met the criteria for the meta-analysis. Prevalence rates of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals ranged from 10.8% to 97.9%. The neck was the body region affected most often (58.5%, 95% CI = 46.0–71.0) followed by the lower back (56.4%, 95% CI = 46.1–66.8), the shoulder (43.1%, 95% CI = 30.7–55.5) and the upper back (41.1%, 95% CI = 32.3–49.9). Potential occupational risk factors included an awkward working posture, high number of treated patients, administrative work, vibration, and repetition.

Conclusions

Musculoskeletal diseases and pain are a significant health burden for dental professionals. This study showed high prevalence rates for several body regions. Therefore, suitable interventions for preventing musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals are needed.

Background

Musculoskeletal diseases and pain are a major health concern among dental professionals in Western countries. Musculoskeletal diseases are defined as a group of diseases and complaints that affect different structures of the musculoskeletal system. These include the nerves, tendons, muscles, joints, ligaments, bones, blood vessels, and supporting structures such as intervertebral discs [1–3]. Musculoskeletal diseases and pain can occur from a single or cumulative trauma and cause pain or sensory disturbances in various regions of the body like the back, neck or shoulders. They can develop either as acute or chronic conditions—the latter are common, representing 30 to 40% of all chronic diseases [2,3]. Some studies have reported that musculoskeletal diseases and pain considerably contribute to reduced productivity and poorer quality of work, decreased job satisfaction, occupational accidents, sick leave, and leaving the profession via premature retirement. Moreover, musculoskeletal diseases and pain can result in high expenditures for medical treatments [1,2,4,5]. In Germany, for instance, the medical costs for musculoskeletal diseases and pain amounted to 34.2 billion euros in 2015, equaling 10.1% of all medical expenditures [6].

Having a healthy musculoskeletal system is especially important for dental professionals, as dentistry is a physically and mentally demanding occupation. In their work, dental professionals have to perform precise hand movements, use vibrating instruments, adopt static postures, use psychomotor skills, and perform repetitive monotonous tasks over long periods of time [7]. As a result, it is necessary to have a deep understanding of the development and the occupational etiology of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals. Musculoskeletal diseases and pain are influenced by various factors, including physical (e.g., height, weight, sex), occupational (e.g., overuse of a body region, uncomfortable posture, insufficient breaks), and socio-psychological characteristics (e.g., high work intensity, stress) [8].

There are some systematic literature reviews focusing on the morbidity and etiology of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals. The last one was published by Hayes et al. in 2009 [9]. Therefore, a systematic review and assessment of current studies is warranted.

The objective of the current study was to determine the frequency and severity of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals in Western countries. The focus lay on analyzing the prevalence in different regions of the body. Moreover, studies on possible occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal diseases and pain were reviewed.

Methods

The present review was performed systematically in line with the proposal for reporting Meta-analyses Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE checklist) [10].

The study protocol for this review was written in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement [11]. It can be obtained from the corresponding author. The protocol is available in English and documents intended research methods for this review process.

Neither an ethics committee approval nor informed consent were required for the systematic review of published literature. There was no contact to possible study participants at any time.

Eligibility criteria

For the screening and eligibility assessment of identified sources, several criteria were defined in line with the PEOS (population, exposure, outcome, study design) criteria. Studies were included if the study population consisted of dental professionals working in general oral healthcare facilities. Dental professionals comprised, for example: dentists, orthodontists, dental surgeons / hygienists / assistants / technicians, and dental students. The study population was exposed to specific working conditions facing dentistry. The exposure was therefore represented by the occupation in dentistry. Moreover, studies were considered if they analyzed prevalence rates and/or occupational risk factors. Outcome measures were musculoskeletal diseases and/or pain. Musculoskeletal diseases (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome, median mononeuropathy, or osteoarthritis) can be diagnosed by validated and standardized diagnostic methods like laboratory tests based on blood samples, radiographs, computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scanning, arthroscopy and ultrasonography [12,13]. Musculoskeletal pain (e.g., back, neck, and shoulder pain or hand symptoms) is often nonspecific and thus more difficult to be verified. Clinical provocation tests, nerve conduction/muscle tests, sensation tests, and palpation can be used to verify musculoskeletal pain reported by patients [14,15]. All types of pain (e.g., acute vs. chronic, specific vs. nonspecific) were considered. Only observational studies such as cross-sectional studies (prevalence studies), retrospective and prospective cohort studies, and case-control studies were included. The studies had to be published in peer-reviewed journals and accessible as full-text. Appropriate study settings were dental practices, orthodontic practices, dental clinics / hospitals, and dental schools. The authors only selected studies published in English.

Filter criteria

In addition to the eligibility criteria some filter criteria were defined during the later review process. After the full-text screening and following eligibility assessment, 179 studies were considered suitable for inclusion based on the predefined eligibility criteria. Especially due to the large number of studies, further exclusion criteria were applied in stages. Firstly, studies published before 2005 were excluded. Secondly, the authors excluded all studies that contained fewer than 50 study participants. Thirdly, studies with less than 50% of quality criteria (see below) met were not considered. Finally, all studies carried out in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America were excluded. Further reasons for selecting these filter criteria were as follows: a) we excluded studies before 2005 for being able to display a current state of knowledge on this topic. Hence we decided to analyze studies not older than 13 years. b) We did not consider studies with fewer than 50 participants as the empirical validity is assumed to be limited in smaller studies. c) We excluded studies from developing countries (Africa, Asia, Central and South America) as working conditions of dental professionals and occupational safety differ significantly from those in industrialized countries. The comparability of study results would not be given.

Information sources and search strategy

The systematic database search was carried out from June to July 2016 in MEDLINE, CINAHL, LIVIVO, Science Direct, PubMed, and Web of Science. Moreover, reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles were hand searched to uncover further sources. Other scientific experts of this study topic were contacted by email to receive additional information about current publications.

The following search terms and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used to search all included databases, for instance:

Dent* OR dental personnel OR oral health OR orthodontists

AND

Occupational exposure OR occupational risk* OR risk factors

AND

Musculoskeletal diseases OR musculoskeletal pain OR work-related upper-extremity musculoskeletal disorders.

A detailed description of the general search strategy is provided in S1 Appendix. The strategy was adapted to the setup of the individual database.

A systematic update search in December 2017 revealed 14 further studies fulfilling the eligibility criteria of this review. After the consideration of all filter criteria, 2 studies remained [16,17].

Literature screening

The literature screening and eligibility assessment of the studies were performed independently by two authors (JL and AK). The screening process comprised title and abstract screening as well as full-text screening. For this purpose, a standardized screening instrument was developed. If a study met all specified eligibility and filter criteria, it was included in the review. Disagreements between the two authors were resolved by discussion. JL and AK ultimately agreed on all included studies.

Data collection

Data extraction for the included studies was carried out by JL and AK independently. A standardized data extraction tool was developed for collecting information on study characteristics (e.g., study design, location, setting, study population) and study results (e.g., sample size, prevalence rates, risk estimates). The extraction tool consisted of 20 items. In case of uncertainty, a discussion took place between the authors. JL extracted the detailed data using Microsoft Excel 2013 spreadsheets. If possible, a calculation of missing values was performed. Some study authors were contacted by email to obtain more information on the presented results or missing data.

Quality assessment

Following the screening and data extraction, the included studies were assessed in terms of study quality. The assessment was performed by two authors (JL and AK) independently. Diverging results were discussed and resolved among the authors. A standardized instrument was created for this quality assessment. It comprised 10 items that were categorized in 6 quality criteria (Table 1). All items were taken from two well-validated checklists [18–20] and modified. The items (e.g., “the study population was clearly described”) were to be answered with “yes” (1 point), “no” (0 points), or “unclear” (0 points). The study quality was finally assessed by adding up the points. This yielded a scale from 0 to 10. Only studies with at least five points were included. Studies with a score from 10 to 8 were considered of high quality and studies with a score from 7 to 5 of moderate quality.

Table 1. Checklist for the quality assessment of studies analyzing MSDs/MSP among dental professionals.

| Number | Criterion | Item |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Study purpose | A specific, clearly stated purpose of the study was described.* |

| 2 | Study design | A prospective/retrospective design was used.** |

| 3 | Study population | The study population was clearly described.* |

| 4 | The participation rate was ≥ 70% (baseline).** | |

| 5 | Assessment of exposure | The occupational exposure was clearly defined.** |

| 6 | The exposure was assessed by a standardized method.** | |

| 7 | Assessment of outcome | The outcome was clearly defined.** |

| 8 | The outcome was assessed by a standardized method.** | |

| 9 | Analysis and data presentation | Risk estimates or raw data were given.* |

| 10 | The study controlled for confounding.* |

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

A meta-analysis was conducted to enable comparability of prevalence data from different studies. Data on prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases and pain were extracted and pooled using the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet developed by Neyeloff et al. [21]. Pooled prevalence rates were calculated separately by the prevalence period for the total prevalence and for prevalence in different body regions. Only studies that used the following prevalence periods were considered: point (current), weekly (7 days) and annual (12 months) prevalence. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistics with I2 ≥ 25% considering low, ≥ 50% moderate and ≥ 75% high heterogeneity [22]. If heterogeneity of the effects between studies existed, random- effects models were used to compute the pooled effect estimate for the prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases and pain. The pooled prevalence rates were reported with 95% confidence intervals.

Depending on availability, we report odds ratios (OR) or adjusted OR (AOR) from studies analyzing risk factors for musculoskeletal diseases and pain. No meta-analysis was performed for this part, as the exposures and outcomes were not homogenously defined.

Results

Study selection

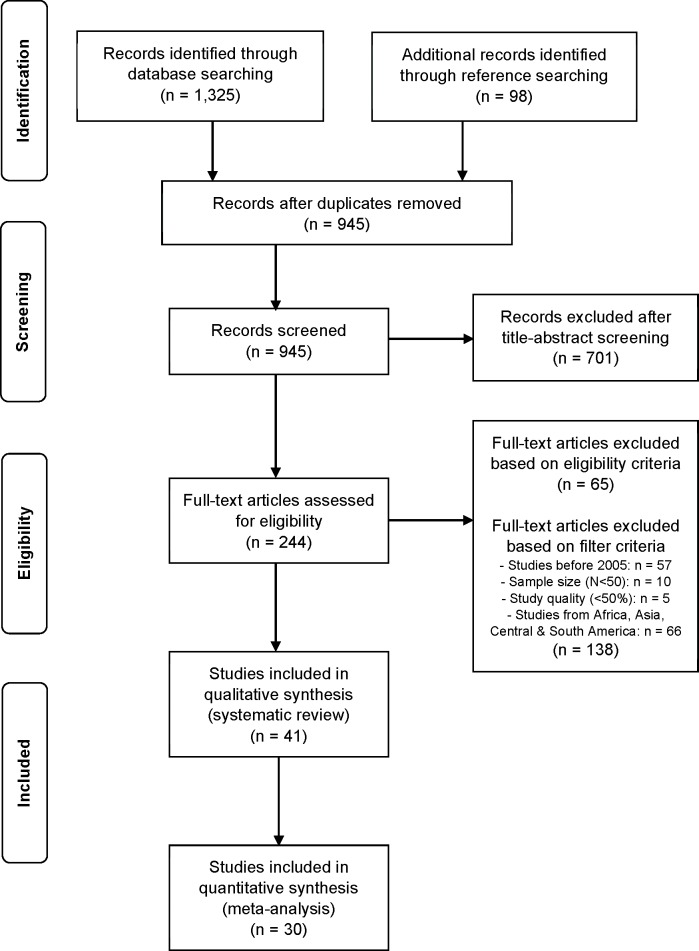

The literature search yielded 1,325 titles (Fig 1). Through reference searching, 98 additional studies were found. After adjusting for duplicates, 945 titles remained. Of these, 701 studies were excluded after the title- and abstract screening, as they did not fulfill the eligibility criteria. Of the remaining 244 studies that were subjected to the full-text screening, 65 did not meet the eligibility criteria. Based on the additional filter criteria, 138 sources were excluded afterwards. Main reasons for exclusion from this review were a different study topic (e.g., interventions related to MSDs/MSP), study population (e.g., patients) or a divergent study design (e.g., review, intervention study). In the end, 41 studies were considered suitable to be included in this review. They comprised 33 cross-sectional studies, 3 cohort studies and 5 case-control studies. Of these, 30 studies (73.1%) met the criteria for the meta-analysis. Reasons for exclusion of 11 studies [17,23–32] from the meta-analysis were a differing prevalence period or missing prevalence data.

Fig 1. Study selection process for this systematic review (PRISMA flowchart).

Study characteristics

All included sources were observational studies analyzing prevalence rates and/or occupational risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals. They were published in English between 2005 and 2017, with the most studies issued per year in 2006 (n = 7; Table 2). In line with the fourth filter criterion, all studies were conducted in Western countries. Approximately half of the studies (n = 23) came from Europe (e.g., Sweden, Finland, Croatia, and Spain) and one quarter each from North America (USA; n = 10) and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand; n = 8). Seventeen studies (41.4%) took place in general dental practices, 16 (39.0%) in dental hospitals/clinics, 15 (36.5%) in dental schools, 5 (12.1%) in orthodontic practices, and one study (2.4%) in an endodontic practice. Some studies were carried out in multiple settings.

Table 2. Study characteristics of included studies analyzing MSDs/MSP among dental professionals (n = 41).

| Reference | Country | Setting | Study population | Sample size (N) | Dental profes-sionals (n) | Prevalence: period of timea | Prevalence: study outcome | Prevalence of MSDs/MSP (n+, %)b,c | Occupational risk factors | Study quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional studies (n = 33) | ||||||||||

| Abou-Atme 2006 [33] | Italy, Europe & Lebanon, Asia | dental school, university | dental students, non-dental students | 530 | 292 | current | a) TMJ pain; b) TMJ sounds | a) Italian dental students: 21 (18.4), Lebanese dental students: 25 (14.0); b) Italian dental students: 38 (33.3), Lebanese dental students: 48 (27.0) |

not surveyed | 5 (moderate) |

| Ayers 2009 [7] | New Zealand, Oceania | dental practice | dentists | 566 | 566 | 7 days, 12 months | MSP (general) | see Table 3 | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Cherniack 2006 [51] | USA, North America | dental hospital/clinic, dental school | dental hygienists, dental hygiene students | 160 | 160 | 12 months | a) MSP; b) CTS |

a) 108 (67.5); b) 20 (12.5) |

vibration | 8 (high) |

| Ding 2007 [25] | Finland, Europe | dental practice, schools | dentists, teachers | 543 | 295 | 1 month | osteoarthritis | 32 (10.8) | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Gijbels 2006 [14] | Belgium, Europe | dental practice, dental hospital/clinic | dentists | 388 | 388 | current | MSDs (general) | 43 (11.0) | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Harutunian 2011 [23] | Spain, Europe | dental school | teaching faculty members, dental students | 74 | 74 | 6 months | MSDs (general) | 59 (79.7) | not surveyed | 8 (high) |

| Hayes 2009a [34] | Australia, Oceania | dental school | dental hygiene students | 126 | 126 | 12 months | MSP (general) | see Table 3 | administrative work | 9 (high) |

| Hayes 2012 [27] | Australia, Oceania | dental practice, orthodontic practice | dental hygienists | 560 | 560 | not stated | MSDs (general) | not stated | workplace, hand scaling, sonic/ ultrasonic scaling | 7 (moderate) |

| Hayes 2013 [35] | Australia, Oceania | dental practice, orthodontic practice | dental hygienists | 560 | 560 | 12 months | MSP (general) | see Table 3 | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Hodacova 2015 [36] | Czech Republic, Europe | dental practice, orthodontic practice, dental hospital/clinic | dentists | 575 | 575 | 12 months | MSDs (general) | 563 (97.9) | workload/job demand, number of treated patients | 9 (high) |

| Humann 2015 [37] | USA, North America | dental hospital/clinic | dental hygienists | 488 | 488 | current | MSDs (general) | 468 (95.9) | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Kierklo 2011 [38] | Poland, Europe | dental practice, orthodontic practice, dental hospital/clinic | dentists | 220 | 220 | current | MSDs (general) | 202 (91.8) | not surveyed | 5 (moderate) |

| Kulcu 2010 [39] | West Turkey, Europe | dental school | dentists, dental nurses, dental students | 206 | 206 | current | a) low back pain; b) neck pain |

a) 125 (60.6); b) 70 (33.9) |

not surveyed | 6 (moderate) |

| Leggat 2006 [40] | Australia, Oceania | dental practice, dental hospital/clinic | dentists | 285 | 285 | 12 months | MSDs (general) | 249 (87.3) | not surveyed | 8 (high) |

| Lindfors 2006 [41] | Sweden, Europe | dental hospital/clinic | dental professionals (dentists, dental hygienists, dental nurses) | 945 | 945 | current | MSDs (general) | 765 (80.9) | not surveyed | 9 (high) |

| Nordander 2013 [57] | Sweden, Europe | dental practice, dental hospital/clinic | dentists, dental hygienists | not stated | 84 | 7 days, 12 months | MSDs (general) | 55 (65.5), 81 (96.4) | not surveyed | 6 (moderate) |

| Palliser 2005 [42] | New Zealand, Oceania | dental practice, dental hospital/clinic | dentists | 413 | 413 | 7 days, 12 months | MSP (general) | see Table 3 | not surveyed | 9 (high) |

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | Serbia, Europe | dental practice, orthodontic practice, dental hospital/clinic | dental professionals (dentists, oral surgery specialists, endodontists, orthodontists, prosthodontics, general dental consultants, pediatric dental consultants) | 356 | 356 | current | a) MSDs (general); b) CTS |

a) 294 (82.5); b) 81 (22.8) |

working time (hours/days), no breaks, number of treated patients, time of conversation with patients, administrative work, awkward working posture | 9 (high) |

| Peros 2011 [43] | Croatia, Europe | dental school | dental students | 152 | 152 | current | back pain | 95 (62.5) | not surveyed | 8 (high) |

| Puriene 2008 [44] | Lithuania, Europe | dental practice, dental hospital/clinic | dentists | 1,670 | 1,670 | 12 months | a) acute MSDs (general); b) chronic MSDs (general) |

a) 1,445 (86.5); b) 651 (38.9) |

not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Rising 2005 [28] | USA, North America | dental school | dental students | 271 | 271 | 3 months | MSDs (general) | 170 (62.7) | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Rythkonen 2006 [52] | Finland, Europe | dental hospital/clinic | dentists | 295 | 295 | current | hand symptoms | 142 (48.1) | working tasks (general) | 8 (high) |

| Sakzewski 2015 [45] | Australia, Oceania | not described | dentists, orthodontists | 466 | 466 | 7 days, 12 months | MSDs (general) | 196 (42.0), 401 (86.0) | not surveyed | 8 (high) |

| Samotoi 2008 [46] | New Zealand, Oceania | not described | dental therapists | 323 | 323 | 7 days, 12 months | MSP (general) | see Table 3 | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Shaffer 2012 [24] | USA, North America | dental school | dental students | 55 | 55 | 6 months | median mononeuro-pathy | 6 (10.9) | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Solovieva 2006 [29] | Finland, Europe | dental practice, dental hospital/clinic | dentists | 291 | 291 | 10 years | Osteoarthritis a) general; b) thumb, index & middle fingers; c) ring & little fingers |

a) 140 (48.1); b) 70 (24.0); c) 134 (46.0) |

being dental professional, working tasks (general) | 8 (high) |

| Sustova 2013 [47] | Czech Republic, Europe | not described | dentists | 581 | 581 | 12 months | MSDs (general) | 557 (95.8) | not surveyed | 8 (high) |

| Thornton 2008 [48] | USA, North America | dental school, dental hospital/clinic | dental students | 590 | 590 | 12 months | MSDs (general) | 358 (60.6) | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Vodanovic 2016 [17] | Croatia, Europe | dental practice | dentists | 506 | 506 | past years | MSP (general) | see Table 3 | not surveyed | 6 (moderate) |

| Warren 2010 [30] | USA, North America | dental school, dental hospital/clinic | dental hygienists, dental hygiene students | 160 | 160 | not stated | MSDs (general) | not stated | vibration, repetition, awkward working posture | 8 (high) |

| Yee 2005 [49] | USA, North America | dental practice | dental hygienists | 529 | 529 | 12 months | MSDs (general) | 482 (91.1) | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Zarra 2014 [58] | Greece, Europe | endodontic practice | endodontists | 120 | 120 | 12 months | MSDs (general) | 73 (60.8) | number of treated patients, awkward working posture | 8 (high) |

| Zitzmann 2008 [50] | Switzerland, Europe | dental practice | dentists, dental hygienists, dental assistants | 1,945 | 1,945 | 7 days | MSP (general) | see Table 3 | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Cohort studies (n = 3) | ||||||||||

| Ding 2011 [26] | Finland, Europe | dental practice, schools | dentists, teachers | baseline: 543, follow up: 482 | baseline: 295, follow up: 264 | 1 month at both surveys | osteoarthritis | baseline: 32 (10.8), 4 year follow up: not stated | not surveyed | 10 (high) |

| Marklund 2008 [53] | Sweden, Europe | dental school | dental students | baseline: 371, follow up: 308 | baseline: 371, follow up: 308 | current at both surveys | a) jaw muscle symptoms; b) jaw muscle signs; c) myofascial pain |

a) baseline: 41 (11.0), 1 year follow up: 47 (15.2); b) baseline: 129 (34.7), 1 year follow up: 138 (44.8); c) baseline: 25 (6.7), 1 year follow up: 24 (7.8) |

not surveyed | 8 (high) |

| Morse 2007 [54] | USA, North America | dental school, dental hospital/clinic | dental hygienists, dental hygiene students | 160 | 160 | 12 months | MSP (general) | see Table 3 | being dental professional, working tasks (general), awkward working posture | 6 (moderate) |

| Case-control studies (n = 5) | ||||||||||

| Cherniack 2008 [55] | USA, North America | not described | dental hygienists, shipyard workers | baseline: 308, follow up: 201 | baseline: 94, follow up: 66 | current at both surveys | CTS | baseline: 14 (14.9), 2 year follow up: 6 (9.0) | not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

| Ding 2010 [56] | Finland, Europe | not described | dentists, teachers | 543 | 295 | current | osteoarthritis | LH: 24 (8.1), RH: 32 (10.8) | dental instruments | 8 (high) |

| Marklund 2010 [31] | Sweden, Europe | dental school | dental students | baseline: 280, follow ups: not stated | baseline: 280, follow ups: not stated | 1 month, 12 months, 2 years | a) TMD symptoms; b) TMD signs; c) TMJ signs/ symptoms; d) jaw muscle signs/ symptoms |

a) baseline: 70 (25.0); b) baseline: 129 (46.0); c) baseline: 84 (30.0), 1st year follow-up: 86 (12.0), 2nd year follow-up: 125 (28.0); d) baseline: 104 (37.1), 1st year follow-up: 132 (27.0), 2nd year follow-up: 148 (26.0) |

not surveyed | 10 (high) |

| Marklund 2010a [32] | Sweden, Europe | dental school | dental students | baseline: 280, follow ups: not stated | baseline: 280, follow ups: not stated | 1 month, 12 months, 2 years | a) TMD symptoms; b) jaw pain; c) spinal pain; d) TMD pain |

a) 2nd

year follow-up: 48 (17.1); b) 2nd year follow-up: 49 (17.5); c) 2nd year follow-up: 63 (22.5); d) 2nd year follow-up: 33 (11.7) |

not surveyed | 10 (high) |

| Werner 2005 [15] | USA, North America | dental school, agencies | dental students, dental hygiene students, clerical workers | 507 | 343 | 12 months | a) CTS; b) shoulder tendinitis; c) elbow tendinitis; d) wrist/hand/ finger tendinitis |

a) 2 (0.58); b) 8 (2.33); c) 1 (0.29); d) 5 (1.45) |

not surveyed | 7 (moderate) |

Abbreviations: CTS: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, LH: left hand, MSDs/MSP: musculoskeletal diseases/musculoskeletal pain, RH: right hand, TMD: temporomandibular disorders, TMJ: temporomandibular joint, USA: United States of America

a If the period of time is not stated in the study, it is labeled as “current” in this review.

b If written in italic letters, incidence of MSDs/MSP was reported only.

c If “see Table 3”, prevalence of MSDs/MSP was reported for body regions only.

A variety of dental professionals represented the sample in the included studies, for instance: dentists, orthodontists, dental hygienists, dental nurses, dental therapists, and dental students. Dentists were the most common study participants (n = 20, 48.7%), followed by dental students (n = 15, 36.5%), and dental hygienists (n = 11, 26.8%). The sample size ranged from 55 to 1,945 subjects, with an average of 448 subjects. Twenty-five studies (60.9%) analyzed musculoskeletal diseases or pain in general and 16 studies (39.1%) focused on a certain disease or kind of pain (e.g., CTS, osteoarthritis, back pain, TMJ pain). The most frequently used survey instrument was questionnaires (n = 24, 58.7%) [7,16,17,23,27, 28,33–50], followed by clinical examinations (n = 15, 36.5%) [14,15,24–26,29–32,51–56], posture analyses (n = 1, 2.4%) [57], and interviews (n = 1, 2.4%) [58].

Prevalence rates of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals varied from 10.8% to 97.9%. The highest prevalence rate (97.9%) was reported in a high quality study for dentists suffering from musculoskeletal diseases in general within the previous 12 months [36]. With respect to the prevalence period, the point prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases and pain ranged from 11.0% to 95.9%, with a pooled prevalence rate of 58.0% (95% CI = 38.8–77.2, I2 = 98.8%, n = 12). The annual prevalence varied from 12.5% to 97.9%, with a pooled prevalence rate of 78.0% (95% CI = 60.2–95.8, I2 = 98.1%, n = 10).

Eight studies [16,24–26,29,51,55,56] examined the prevalence of particular musculoskeletal diseases among dental professionals. They have been diagnosed by clinical examinations including neuromuscular examinations, provocation and nerve conduction tests, vibration sensory tests, or x-rays depending on the analyzed study outcome. The prevalence of CTS among dental professionals ranged from 12.5% to 22.8% (n = 3). Prevalence rates of osteoarthritis varied from 10.8% to 48.1% (n = 4). One study reported the prevalence of median mononeuropathy (10.9%).

Based on the ten quality criteria, 20 studies (48.7%) were classified as high quality (8–10 points) [16,23,26,29–32,34,36,40–43,45,47,51–53,56,58] and 21 studies (51.3%) as moderate quality (5–7 points) [7,14,15,17,24,25,27,28,33,35,37–39,44,46,48–50,54,55,57], with an average of 7.5 points. Due to the third filter criterion, there were no studies of low quality. The most common reasons for a moderate methodological quality were weaknesses in study design, data analysis and response rate.

Prevalence by body region

Several studies examined the prevalence in selected regions of the body (Table 3). In this review, the 10 most frequently analyzed body regions are displayed in descending order. The neck was the most frequently affected body region (in 15 out of 23 studies) [7,16,23,24,34–36,40,42,45–50], followed by the back (in 5 out of 23 studies) [14,17,38,42,44] and the shoulders (in 3 out of 23 studies) [37,45,54]. The annual prevalence of neck pain was between 29.1% and 84.8%. Back pain in general showed annual prevalence rates from 26.7% to 57.1%. That of lower back pain was higher and ranged from 28.5% to 74.9%. Shoulder pain had annual prevalence rates between 6.1% and 69.6%. The weekly prevalence of neck pain varied from 19.7% to 75.0%, that of lower back pain from 21.0% to 28.5% and that of shoulder pain from 16.7% to 28.9%. The point prevalence of neck pain was between 33.1% and 49.5%. Lower back pain showed point prevalence rates from 29.3% to 70.0%, and shoulder pain from 20.0% to 34.6%.

Table 3. Selected studies analyzing the prevalence of MSDs/MSP among dental professionals stratified by body region and period of time (n = 23).

| Reference | Dental profes-sionals (n) | Prevalence: period of timea | Backb (n+, %) |

Neck (n+, %) |

Hand/wrist (n+, %) |

Shoulder (n+, %) | Elbow (n+, %) |

Hip (n+, %) |

Knee (n+, %) |

Foot/ankle (n+, %) | Arm (n+, %) |

Leg (n+, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayers 2009 [7] | 566 | 7 days, 12 months | UB: 70 (12.3), 169 (29.8), LB: 120 (21.2), 325 (57.4) |

112 (19.7), 332 (58.6) | 56 (10.0), 141 (24.9) | 95 (16.7), 257 (45.4) | 23 (4.0), 57 (10.0) | 30 (5.3), 84 (14.8) | 54 (9.5), 118 (20.8) | 34 (6.0), 74 (13.0) | not stated | not stated |

| Gijbels 2006 [14] | 388 | current | LB: 209 (53.8) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Harutunian 2011 [23] | 74 | 6 months | 30 (40.5), LB: 39 (52.7) | 43 (58.1) | 20 (27.0) | 18 (24.3) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Hayes 2009a [34] | 126 | 12 months | UB: 52 (41.2), LB: 72 (57.1) |

81 (64.2) | 52 (41.2) | 60 (47.6) | 7 (5.5) | 14 (11.1) | 33 (26.1) | 16 (12.6) | 8 (6.3) | 4 (3.1) |

| Hayes 2013 [35] | 560 | 12 months | UB: 346 (61.7), LB: 380 (67.8) |

475 (84.8) | 336 (60.0) | 390 (69.6) | 77 (13.7) | 92 (16.4) | 58 (10.3) | 56 (10.0) | 122 (21.7) | 31 (5.5) |

| Hodacova 2015 [36] | 575 | 12 months | UB: 286 (49.7), LB: 431 (74.9) |

449 (78.0) | 223 (38.7) | 300 (52.1) | 163 (28.3) | 231 (40.1) | 217 (37.7) | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Humann 2015 [37] | 488 | current | UB: 145 (29.7), LB: 143 (29.3) |

162 (33.1) | 101 (20.6) | 169 (34.6) | not stated | 84 (17.2) | not stated | not stated | 94 (19.2) | not stated |

| Kierklo 2011 [38] | 220 | current | 44 (20.0), LB: 154 (70.0) | 103 (46.8) | 104 (47.2) | 44 (20.0) | 33 (15.0) | not stated | 35 (15.9) | 34 (15.4) | not stated | not stated |

| Leggat 2006 [40] | 285 | 12 months | UB: 98 (34.3), LB: 153 (53.6) |

164 (57.5) | 96 (33.6) | 152 (53.3) | 37 (12.9) | 36 (12.6) | 54 (18.9) | 33 (11.5) | not stated | not stated |

| Morse 2007 [54] | 160 | 12 months | not stated | not stated | not stated | 43 (26.8) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Palliser 2005 [42] | 413 | 7 days, 12 months | UB: 72 (17.4), 133 (32.2), LB: 118 (28.5), 260 (62.9) |

111 (26.8), 260 (62.9) | 86 (20.8), 172 (41.6) | 101 (24.4), 202 (48.9) | 34 (8.2), 69 (16.7) | 39 (9.4), 88 (21.3) | 47 (11.3), 90 (21.7) | 37 (8.9), 73 (17.6) | not stated | not stated |

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | 356 | current | LB: 163 (45.7) | 176 (49.5) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Puriene 2008 [44] | 1,670 | 12 months | acute: 1,520 (91.0), chronic: 954 (57.1) | not stated | acute: 1,388 (83.1), chronic: 508 (30.4) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Sakzewski 2015 [45] | 466 | 7 days, 12 months | UB: 90 (19.3), 104 (22.3), LB: 130 (27.8), 133 (28.5) |

130 (27.8), 143 (30.6) | 68 (14.5), 78 (16.7) | 135 (28.9), 143 (30.6) | 35 (7.5), 39 (8.3) | 55 (11.8), 60 (12.8) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Samotoi 2008 [46] | 323 | 7 days, 12 months | UB: 47 (14.5), 98 (30.3), LB: 68 (21.0), 167 (51.7) |

84 (26.0), 179 (55.4) | 76 (23.5), 149 (46.1) | 85 (26.3), 164 (50.7) | 31 (9.5), 72 (22.2) | 40 (12.3), 74 (22.9) | 25 (7.7), 54 (16.7) | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Shaffer 2012 [24] | 55 | 6 months | not stated | 15 (27.2) | 3 (5.4) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | 15 (27.2) | not stated |

| Sustova 2013 [47] | 581 | 12 months | UB: 286 (49.2), LB: 431 (74.1) |

449 (77.2) | 223 (38.3) | 300 (51.6) | 163 (28.0) | 231 (39.7) | 217 (37.3) | not stated | not stated | 204 (35.1) |

| Thornton 2008 [48] | 590 | 12 months | 158 (26.7) | 172 (29.1) | 72 (12.2) | 111 (18.8) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Vodanovic 2016 [17] | 506 | past years | UB: 386 (76.2), LB: 379 (74.9) |

not stated | 372 (73.5) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | 276 (54.5) | |

| Werner 2005 [15] | 343 | 12 months | not stated | not stated | 69 (20.1) | 21 (6.1) | 55 (16.0) | not stated | not stated | not stated | see elbow | not stated |

| Yee 2005 [49] | 529 | 12 months | UB: 323 (61.0), LB: 331 (62.5) |

395 (74.6) | 354 (66.9) | 321 (60.6) | 154 (29.1) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

| Zarra 2014 [58] | 120 | 12 months | LB: 36 (30.0) | 36 (30.0) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | 64 (53.3) | 13 (10.8) |

| Zitzmann 2008 [50] | 1,945 | 7 days | 1,400 (71.9) | 1,459 (75.0) | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated | not stated |

Abbreviations: LB: lower back, UB: upper back

a If the period of time is not stated in the study, it is labeled as “current” in this review.

b If no explanation is given, the prevalence belongs to the back in general.

Our meta-analysis showed consistent results for all prevalence periods, except point prevalence (Table 4). The greatest annual prevalence was observed for the neck 58.5% (95% CI = 46.0–71.0), the lower back 56.4% (95% CI = 46.1–66.8), the shoulders 43.1% (95% CI = 30.7–55.5), and the upper back 41.1% (95% CI = 32.3–49.9). The weekly prevalence was considerably lower: 35.1% (95% CI = 12.7–57.5), 24.5% (95% CI = 20.5–28.5), 23.9% (95% CI = 18.0–29.8), and 15.7% (95% CI = 12.5–18.9), respectively. In contrast to this, the highest point prevalence was indicated for the lower back 49.2% (95% CI = 33.0–65.4), the neck 42.8% (95% CI = 31.5–54.0), the hand/wrist 33.6% (95% CI = 7.6–59.6), and the shoulders 27.3% (95% CI = 13.0–41.7). For all examined body regions and periods of time, significant heterogeneity was observed between the included studies (I2 22.3–99.2%). Heterogeneity was particularly high (> 84%) in 21 (out of 27) cases.

Table 4. Pooled prevalence rates of MSDs/MSP among dental professionals stratified by body region and period of time.

| Prevalence: period of timea,b | Back (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Upper back (%, CI, I2c, n) | Lower back (%, CI, I2c, n) | Neck (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Hand/wrist (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Shoulder (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Elbow (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Hip (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Knee (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Foot/ankle (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Arm (%, CI, I2c, n) |

Leg (%, CI, I2c, n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | n/a | n/a |

49.2

(33.0–65.4) 95.2 (n = 4) |

42.8

(31.5–54.0) 87.0 (n = 3) |

33.6 (7.6–59.6) 96.3 (n = 2) |

27.3

(13.0–41.7) 92.4 (n = 2) |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| 7 days | n/a |

15.7

(12.5–18.9) 66.7 (n = 4) |

24.5

(20.5–28.5) 66.5 (n = 4) |

35.1

(12.7–57.5) 99.2 (n = 5) |

16.9 (10.8–22.9) 90.4 (n = 4) |

23.9 (18.0–29.8) 85.1 (n = 4) |

7.1 (4.5–9.7) 77.5 (n = 4) |

9.5 (5.9–13.1) 84.4 (n = 4) |

9.4

(7.5–11.4) 22.3 (n = 3) |

7.2 (4.4–10.1) 62.9 (n = 2) |

n/a | n/a |

| 12 months |

41.9

(12.2–71.7) 99.1 (n = 2) |

41.1

(32.3–49.9) 95.5 (n = 10) |

56.4

(46.1–66.8) 95.5 (n = 11) |

58.5

(46.0–71.0) 97.3 (n = 12) |

35.9 (27.8–44.0) 97.4 (n = 13) |

43.1 (30.7–55.5) 98.4 (n = 13) |

17.2 (12.5–21.9) 94.3 (n = 11) |

21.2 (14.8–27.6) 95.2 (n = 9) |

23.6 (16.3–30.8) 95.3 (n = 8) |

12.8 (10.1–15.4) 60.3 (n = 5) |

25.7 (8.4–43.1) 96.5 (n = 3) |

13.5 (1.7–25.3) 97.8 (n = 4) |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval, n/a: not applicable

a If the period of time is not stated in the study, it is labeled as “current” in this review.

b No pooled prevalence rates were calculated for the “6 months” or “past years” prevalence periods due to low use in the original studies.

c I2 statistics: ≥ 25% considered low, ≥ 50% moderate and ≥ 75% high heterogeneity.

Occupational risk factors

In the literature, a number of possible occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals have been identified. Findings of selected studies are displayed in Table 5. A review of the included studies revealed 15 occupational risk factors.

Table 5. Selected studies analyzing occupational risk factors for MSDs/MSP among dental professionals (n = 11).

| Reference | Risk factor (predictor)a | MSDs/MSP (outcome)b | OR | 95%-CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profession | |||||

| 1. Being dental professional | |||||

| Morse 2007 [54] | being dental hygienist (ref. (non-) dental students) |

neck pain | 3.50 | 1.80–6.90* | <0.05 |

| shoulder pain | 2.70 | 1.20–5.90* | <0.05 | ||

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| neck pain | 5.00 | 1.70–15.00* | <0.05 | ||

| shoulder pain | 2.70 | 1.20–5.90* | <0.05 | ||

| Solovieva 2006 [29] | being dental specialist (ref. general dental practitioners) |

osteoarthritis in any finger joint | 1.22 | 0.63–2.35 | ns |

| Workplace | |||||

| 2. Workplace | |||||

| Hayes 2012 [27] | general private practice (ref. other practices) |

shoulder pain | 1.53 | 1.00–2.34* | <0.05 |

| Hayes 2012 [27] | periodontal practice (ref. other practices) |

forearm pain | 2.42 | 1.19–4.90** | <0.01 |

| Work schedule | |||||

| 3. Working time (hours/days) | |||||

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | number of working days/week | MSP | 0.60 | 0.47–0.77*** | <0.001 |

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| MSP | 0.92 | 0.55–1.56 | ns | ||

| 4. No breaks | |||||

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | no break between interventions | MSP | 6.89 | 3.80–12.50*** | <0.001 |

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| MSP | 6.51 | 2.58–16.41*** | <0.001 | ||

| 5. Workload/job demand | |||||

| Hodacova 2015 [36] | psychologically demanding work | low back pain | 1.89 | 1.23–2.88** | <0.01 |

| neck pain | 2.90 | 1.83–4.59** | <0.01 | ||

| shoulder pain | 1.83 | 1.12–3.01* | <0.05 | ||

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| neck pain | 2.39 | 1.46–3.89** | <0.01 | ||

| Patients | |||||

| 6. Number of treated patients | |||||

| Hodacova 2015 [36] | >20 patients/day (ref. <20 patients) |

low back pain | 1.56 | 1.11–2.20* | <0.05 |

| neck pain | 1.36 | 1.00–1.92* | <0.05 | ||

| shoulder pain | 1.50 | 1.03–2.20* | <0.05 | ||

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | average number of patients | MSP | 0.95 | 0.93–0.97*** | <0.001 |

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| MSP | 0.96 | 0.94–0.98*** | <0.001 | ||

| Zarra 2014 [58] | 6–8 patients/day (ref. <6 patients) |

MSDs | 3.52 | 1.68–18.10* | <0.05 |

| 7. Time of conversation with patients | |||||

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | time of conversation with patients | MSP | 3.16 | 1.45–6.89*** | <0.001 |

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| MSP | 2.13 | 0.52–8.71 | ns | ||

| Working tasks | |||||

| 8. Working tasks (general) | |||||

| Morse 2007 [54] | number of hours of cleaning teeth | neck pain | 2.10 | 1.20–3.90* | <0.05 |

| Morse 2007 [54] | amount of polishing teeth | shoulder pain | 2.50 | 1.40–4.50* | <0.05 |

| Rythkonen 2006 [52] | total time during work history in dental filling and root treatment | finger symptoms | |||

| (medium) | 1.46 | 0.80–2.68 | ns | ||

| (high) | 1.92 | 1.03–3.60* | <0.05 | ||

| (ref. low) | |||||

| Rythkonen 2006 [52] | average hours/week spent on dental filling and root treatment during the past 12 months | finger symptoms | |||

| (medium) | 1.50 | 0.83–2.71 | ns | ||

| (high) | 1.06 | 0.56–2.00 | ns | ||

| (ref. low) | |||||

| Solovieva 2006 [29] | cluster 2: 50% restorative treatments and endodontics, 50% prosthodontics, periodontics and surgical treatments | osteoarthritis in any finger joint | 1.68 | 0.81–3.46 | ns |

| cluster 3: 100% restorative treatments and endodontics | 1.59 | 0.86–2.93 | ns | ||

| (ref. cluster 1: variable working tasks) | |||||

| 9. Administrative work | |||||

| Hayes 2009a [34] | computer-based work (<5 hours) | low back pain | 16.83 | 2.44–138.13** | <0.01 |

| neck pain | 12.89 | 1.92–102.69** | = 0.01 | ||

| (6–10 hours) | shoulder pain | 7.03 | 1.42–39.49* | <0.05 | |

| upper back pain | 5.29 | 1.21–25.56* | <0.05 | ||

| Hayes 2009a [34] | desk-based work (16–20 hours) (ref. <5 hours) |

neck pain | 19.70 | 1.34–378.94* | <0.05 |

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | computer-based work | MSP | 1.59 | 1.02–2.48* | <0.05 |

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| MSP | 1.28 | 0.66–2.49 | ns | ||

| 10. Hand scaling | |||||

| Hayes 2012 [27] | hand scaling | neck pain | 4.22 | 1.26–14.09* | <0.05 |

| 11. Sonic/ultrasonic scaling | |||||

| Hayes 2012 [27] | ultrasonic scaling | shoulder pain | 3.11 | 1.20–8.05* | <0.05 |

| upper back pain | 3.43 | 1.24–9.44* | <0.05 | ||

| lower back pain | 2.76 | 1.07–7.13* | <0.05 | ||

| Work equipment | |||||

| 12. Dental instruments | |||||

| Ding 2010 [56] | fingers with low pinch strength | symptomatic osteoarthritis | |||

| (left hand) | 2.00 | 1.10–3.80* | <0.05 | ||

| (right hand) | 3.30 | 1.80–6.20* | <0.05 | ||

| Working conditions | |||||

| 13. Vibration | |||||

| Cherniack 2006 [51] | vibration exposure (years) | weak hand grip | 1.77 | 1.12–2.80* | <0.05 |

| vibration exposure (years), raised VPT | 1.55 | 1.14–2.12* | <0.05 | ||

| Warren 2010 [30] | vibration (hours/day) | cold hands | 1.03 | not stated | ns |

| numb/tingling | 1.08 | not stated | <0.10 | ||

| fingers numb/tingling & cold | 1.05 | not stated | ns | ||

| neck symptoms | 1.05 | not stated | ns | ||

| shoulder symptoms | 0.97 | not stated | ns | ||

| elbow symptoms | 1.09 | not stated | <0.10 | ||

| forearm symptoms | 1.12 | not stated | ns | ||

| back symptoms | 0.96 | not stated | ns | ||

| decrease in hand grip strength | 1.12 | not stated | <0.05 | ||

| CTS right | 1.13 | not stated | <0.05 | ||

| CTS left | 1.10 | not stated | ns | ||

| DeQuervains right | 0.93 | not stated | ns | ||

| ulnar neuritis right | 1.10 | not stated | ns | ||

| ulnar neuritis left | 1.14 | not stated | ns | ||

| flexor tendinitis right | 1.00 | not stated | ns | ||

| flexor tendinitis left | 1.01 | not stated | ns | ||

| extensor tendinitis right | 1.07 | not stated | ns | ||

| extensor tendinitis left | 1.07 | not stated | <0.10 | ||

| 14. Repetition | |||||

| Warren 2010 [30] | repetitive movements | cold hands | 2.16 | not stated | ns |

| numb/tingling | 2.21 | not stated | <0.05 | ||

| fingers numb/tingling & cold | 1.79 | not stated | ns | ||

| neck symptoms | 1.42 | not stated | ns | ||

| shoulder symptoms | 0.77 | not stated | ns | ||

| elbow symptoms | 2.70 | not stated | <0.10 | ||

| forearm symptoms | 2.20 | not stated | ns | ||

| back symptoms | 1.36 | not stated | ns | ||

| decrease in hand grip strength | 2.80 | not stated | <0.05 | ||

| CTS right | 1.65 | not stated | ns | ||

| CTS left | 2.46 | not stated | ns | ||

| DeQuervains right | 439.51 | not stated | ns | ||

| ulnar neuritis right | 0.87 | not stated | ns | ||

| ulnar neuritis left | 0.73 | not stated | ns | ||

| flexor tendinitis right | 7.94 | not stated | <0.05 | ||

| flexor tendinitis left | 2.54 | not stated | ns | ||

| extensor tendinitis right | 1.77 | not stated | <0.10 | ||

| extensor tendinitis left | 1.42 | not stated | ns | ||

| 15. Awkward working posture | |||||

| Morse 2007 [54] | working with a bent neck | neck pain | 2.10 | 1.30–3.40* | <0.05 |

| Morse 2007 [54] | holding arms above shoulder height | shoulder pain | 1.50 | 1.00–2.40* | <0.05 |

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | working in the same position longer than 40 minutes | MSP | 2.65 | 1.43–4.89** | <0.01 |

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| MSP | 2.51 | 1.21–5.17* | <0.05 | ||

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | discomfort while working in a certain body position | MSP | 11.88 | 6.39–22.09*** | <0.001 |

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| MSP | 10.82 | 5.38–21.78*** | <0.001 | ||

| Pejcic 2017 [16] | preferred working position (sitting or standing) |

MSP | 1.63 | 1.11–2.38* | <0.05 |

| multivariate analysis: | |||||

| MSP | 2.02 | 1.20–3.42** | <0.01 | ||

| Warren 2010 [30] | static reach/grip | cold hands | 0.53 | not stated | ns |

| numb/tingling | 1.02 | not stated | ns | ||

| fingers numb/tingling & cold | 0.75 | not stated | ns | ||

| neck symptoms | 0.83 | not stated | ns | ||

| shoulder symptoms | 1.20 | not stated | ns | ||

| elbow symptoms | 0.69 | not stated | ns | ||

| forearm symptoms | 0.67 | not stated | ns | ||

| back symptoms | 0.90 | not stated | ns | ||

| decrease in hand grip strength | 1.48 | not stated | ns | ||

| CTS right | 1.25 | not stated | ns | ||

| CTS left | 1.97 | not stated | ns | ||

| DeQuervains right | 1.03 | not stated | ns | ||

| ulnar neuritis right | 2.00 | not stated | ns | ||

| ulnar neuritis left | 1.82 | not stated | ns | ||

| flexor tendinitis right | 0.96 | not stated | ns | ||

| flexor tendinitis left | 1.05 | not stated | ns | ||

| extensor tendinitis right | 0.70 | not stated | ns | ||

| extensor tendinitis left | 0.95 | not stated | ns | ||

| Zarra 2014 [58] | awkward postures during clinical practice (ref. no awkward postures) |

MSDs | 4.56 | 1.34–15.51* | <0.05 |

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval, CTS: carpal tunnel syndrome, MSDs/MSP: musculoskeletal diseases/musculoskeletal pain, ns: not significant (p>0.05), OR: odds ratio, ref: reference group, VPT: vibrotactile perception thresholds

a If no reference group is given, the information is not stated in the study.

b If a uni- and multivariate regression analysis was conducted, the first results refer to the univariate and the following to the multivariate analysis.

* significant result

** very significant result

*** highly significant result.

The prevalence of musculoskeletal pain seems to be positively associated with being a dental professional. One study found significantly higher odds of suffering from neck or shoulder pain for dental hygienists compared to (non-) dental students (AOR = 5.00, CI = 1.70–15.00, p < 0.05; AOR = 2.70, CI = 1.20–5.90, p < 0.05) [54]. Pejcic et al. reported that having no breaks between interventions significantly increased the odds of musculoskeletal pain (AOR = 6.51, CI = 2.58–16.41, p < 0.001) [16]. Therefore, the work schedule appears to have an important influence on the prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases and pain. Beyond this, another study stated that psychologically demanding work probably caused neck pain among dental professionals (AOR = 2.39, CI = 1.46–3.89, p < 0.01) [36]. Zarra et al. examined the influence of the number of treated patients on the risk of suffering from musculoskeletal diseases. They found that the odds were 3.52 times higher for dental professionals who treated 6 to 8 patients per day in comparison to colleagues treating less than 6 patients (CI = 1.68–18.10, p < 0.05) [58]. Hodacova et al. confirmed this result but for 20 patients per day [36].

In addition, several working tasks appear to be positively correlated with the risk of musculoskeletal pain. One study indicated that an increasing number of hours of cleaning teeth increased the odds of neck pain (OR = 2.10, CI = 1.20–3.90, p < 0.05) [54]. The authors also found that the amount of teeth polishing done is a possible etiological factor for shoulder pain (OR = 2.50, CI = 1.40–4.50, p < 0.05) [54]. Hayes et al. described that hand scaling significantly increased the odds of neck pain (OR = 4.22, CI = 1.26–14.09, p < 0.05) and ultrasonic scaling the odds of shoulder pain (OR = 3.11, CI = 1.20–8.05, p < 0.05), upper back pain (OR = 3.43, CI = 1.24–9.44, p < 0.05), and lower back pain (OR = 2.76, CI = 1.07–7.13, p < 0.05) [27]. Furthermore, the authors stated in a previous study that musculoskeletal pain may have been caused by administrative work. Dental professionals who performed desk-based work for 16–20 hours ran a 19.70 times higher odds of having neck pain than colleagues performing fewer than 5 hours (CI = 1.34–378.94, p < 0.05) [34]. Similar results were reported for computer-based work [34]. One study investigated the influence of vibration on the risk of musculoskeletal diseases, such as CTS. The results indicated that vibration increased the odds of CTS in the right hand by 1.13 times (CIs not stated, p < 0.05) [30].

Moreover, awkward working posture through cramped, twisted and prolonged sitting or standing positions was the most frequently analyzed etiological factor of musculoskeletal diseases and pain. Pejcic et al. demonstrated that discomfort while working in a certain body position probably caused musculoskeletal pain among dental professionals (AOR = 10.82, CI = 5.38–21.78, p < 0.001). The authors also showed that working in the same position longer than 40 minutes significantly increased the odds of musculoskeletal pain (AOR = 2.51, CI = 1.21–5.17, p < 0.05) [16]. These findings were in line with conclusions of other studies [30,54]. Finally, in a study by Zarra et al., dental professionals who worked with awkward postures during clinical practice ran a 4.56 times higher odds of musculoskeletal diseases than colleagues working without awkward postures (CI = 1.34–15.51, p < 0.05) [58].

Discussion

This literature review presents the most current state of research on the prevalence and occupational risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals in Western countries. Our findings were drawn from 41 research articles published from 2005 to 2017. Prevalence rates of musculoskeletal diseases and pain ranged from 10.8% to 97.9%, with a pooled annual prevalence rate of 78.0% (95% CI = 60.2–95.8). In most of the studies, the prevalence rates were high (above 60%). Therefore, dental professionals are particularly at risk of musculoskeletal diseases and pain.

This was also evident when looking at the prevalence rates of the individual body regions. In this review and meta-analysis, the neck was the most frequently affected body region (pooled annual prevalence: 58.5%, 95% CI = 46.0–71.0). Ohlendorf et al. conducted a kinematic analysis of occupational musculoskeletal loadings in several body regions among dentists. The authors observed disadvantageous joint angle distributions in the 75th and 95th percentile of the head and cervical spine during the treatment of patients. This static working posture possibly contributed to particular muscular strains in the neck [59,60]. Some other studies also found high prevalence rates for neck pain (above 66%) among Asian dental professionals [2,61,62]. In the back region, lower back pain (pooled annual prevalence: 56.4%, 95% CI = 46.1–66.8) was most common compared to the back in general (pooled annual prevalence: n/a) and the upper back (pooled annual prevalence: 41.1%, 95% CI = 32.3–49.9). One study observed among dental professionals a characteristic twisting of the back during the treatment of patients, caused by a greater right tilt of the lumbar spine and a left tilt of the thoracic spine [59]. Howarth et al. found similar results in their study and concluded that forced postures while sitting are significantly associated with pain in the lower back. Dental hygienists, for instance, spend 66% of their working time seated, 40% of it with a forward bent trunk posture of 30 degrees [63]. High prevalence rates for lower back pain (above 57%) among Asian dental professionals were also reported by Aljanakh et al. [1], Batham et al. [61] and Kumar et al. [64]. Furthermore, our meta-analysis showed that musculoskeletal diseases and pain were also common in the shoulders (pooled annual prevalence: 43.1%, 95% CI = 30.7–55.5) and in the hand/wrist (pooled point prevalence: 33.6%, 95% CI = 7.6–59.6). Several other studies confirmed this result for Asian dental professionals [2,62,65,66]. These findings suggest that dental professionals primarily use upper body regions at work. Especially during the treatment of patients and administrative work, which account for around 70% of all dental tasks, upper extremities like the hand/wrist or shoulder are increasingly under muscular strain [59]. Thus, dental professionals are particularly vulnerable to musculoskeletal diseases and pain in the shoulder and hand/wrist.

This literature review revealed 15 possible occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals. Our findings indicate that administrative work like desk-based (OR = 19.70, CI = 1.34–378.94) and computer-based (OR = 12.89, CI = 1.92–102.69) work had the highest significant influence on the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain (here: neck pain) [34]. However, the large confidence intervals might indicate that these results are not robust. Several studies found that administrative work on the computer or desk is combined with disadvantageous static sitting positions that may cause twisting, forced postures and eventually diseases or pain in the neck or other body regions [16,30,54,63]. The second most important occupational risk factor was the awkward working posture. Pejcic et al. found that discomfort while working in a certain body position significantly increased the odds of musculoskeletal pain (AOR = 10.82, CI = 5.38–21.78) [16]. Several other studies from Asia and South America found similar results for dental professionals [64,67,68]. Awkward working postures result from specific dental tasks like hand scaling, ultrasonic scaling and cleaning/polishing teeth [27,54]. Consequently, dental professionals are particularly vulnerable to musculoskeletal diseases and pain due to forced postures. In third place, the work schedule seems to be associated with the risk of musculoskeletal diseases and pain. One study reported that having no breaks between interventions significantly increased the odds of musculoskeletal pain by 6.51 times (CI = 2.58–16.41) [16]. Fals Martínez et al. confirmed this finding for South American dental professionals [67]. Insufficient breaks during dental activities that are very demanding to the musculoskeletal system lead to an overstraining of the system. As a consequence, musculoskeletal diseases and pain can occur [16]. Finally, several dental tasks appear to be correlated with the prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases and pain. For instance, Hayes et al. stated that hand scaling may have caused neck pain among dental professionals (OR = 4.22, CI = 1.26–14.09) [27]. One other study from South Africa showed similar results [69]. Some dental tasks like hand scaling increase the risk of musculoskeletal diseases and pain especially due to awkward working postures that are combined with the performance of this dental activity (see above) [27,54].

Ultimately, our findings indicate that many occupational risk factors are associated with musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals. However, it is evident that the individual risk factors were analyzed in only a few studies. Therefore, it was difficult to compare results for the individual risk factors. Furthermore, musculoskeletal diseases and pain are multifactorial [70]. Often, several factors play a role in the development of musculoskeletal diseases and pain, and the respective degree of influence is difficult to determine. Kihun et al. stated that musculoskeletal diseases and pain are influenced by physical, occupational, and socio psychological factors (see background) [8]. Hence, occupational risk factors are one of a number of factors contributing to the causation of musculoskeletal diseases and pain [70]. However, the findings of the current review showed that an occupation in dentistry and its related factors significantly contribute to the development of musculoskeletal diseases and pain.

Moreover, several intervention studies already examined the effectiveness of various preventative measures against musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals [43,71–73]. The studies found, for instance, that regular physical activity before and after work, back exercises, dynamic sitting, and magnification loupes can significantly contribute to the reduction of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals.

Strengths and limitations

This literature review and meta-analysis as well as its included studies contain several methodological strengths and limitations. Firstly, this work only considered studies from Western countries. Therefore, the working conditions and environment of the individual oral healthcare facilities in the studies can be considered as similar. As a consequence, the study results were comparable with each other when focusing on the geographical areas.

Furthermore, the literature search revealed many studies related to the described research topic. However, the research focus of the included sources often varied from each other. The studies used different study designs and outcomes related to musculoskeletal diseases and pain, diverging subgroups according to the study population and different periods of time related to the prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases and pain. The comparability of the study results was limited by this reason so that general conclusions were difficult to make. This weakness was solved by summarizing and pooling the results by topic (e.g., separately for the prevalence period, outcomes, and body regions).

In addition, the included studies used divergent survey instruments like a questionnaire (58.7%) (mainly a modified version of the Standardized Nordic Questionnaire [74]), clinical examination (36.5%) and posture analysis or interview (both 2.4%). The Nordic Questionnaire is a well-validated and common measurement tool that seems to be suitable for examining the prevalence of musculoskeletal diseases and pain [74]. In all cases, the clinical examination, posture analysis, and interview were conducted using standardized well-validated checklists or other survey instruments. Consequently, the results of the included studies were accurate and mutually comparable in this case. It was therefore possible to draw reliable conclusions and generalize the results if they were analyzed and pooled by topic (see above).

The current research topic showed many studies (n = 945) that were suitable for inclusion in this review. Due to the high number of studies additional filter criteria were applied. Overall, 41 studies were included, which correspond to a sufficient number of studies representing relevant data for this review.

Further, this review only considered observational studies from peer reviewed journals and no grey literature. Therefore, a sufficient methodological quality of the studies was ensured. Moreover, there were many missing values in the original studies, but the majority of missing data could be calculated so that presented results only contain few missing values (see Tables 2–5).

The assessment of the methodological study quality was carried out with an instrument based on two standardized, well-validated checklists [18–20]. The instrument was applicable to all types of observational studies that were included. The study quality of included sources was satisfactory, with an average of 7.5 points. Almost half of the studies had a high (48.7%) or moderate (51.3%) quality. By employing the third filter criterion, there were no studies of low quality. However, the quality assessment revealed some weaknesses in methodology. The majority of included studies (n = 37, 90.2%) did not use a prospective or retrospective study design for examining the cause effect relationship between occupational risk factors and musculoskeletal diseases and pain. Likewise, more than half of the studies (n = 25, 60.9%) did not control for confounding in their statistical analyses. The response rate was below 70% in around half of the studies (n = 22, 53.6%).

Our meta-analysis included 30 out of 41 studies that were 73.1%. Reasons for the exclusion of 11 studies were a differing prevalence period or missing prevalence data. The pooled analysis enabled comparability of prevalence data from different studies. The applied analysis tool from Neyeloff et al. [21] was an appropriate and simple option for pooling and weighting prevalence data from several studies. Moreover, significant and high heterogeneity between the included studies was observed, especially resulting from different study designs, study populations, survey instruments, and study outcomes. As a result of this and a small number of studies in the sub-analyses, the described pooled prevalence rates should be interpreted cautiously.

Conclusions

This literature review showed evidence that musculoskeletal diseases and pain are a major health burden for dental professionals. Our findings revealed high prevalence rates for various diseases and types of pain related to the musculoskeletal system. Several body regions were affected by musculoskeletal diseases and pain, especially the neck, back, and shoulders. In addition, many possible occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal diseases and pain could be identified, such as awkward working posture, hand scaling and high number of treated patients. Hence, suitable interventions for preventing musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals are needed. In the long term this could significantly reduce the burden of disease, costs of illness, absenteeism from work, and occupational accidents.

The results of our study are a valuable base for occupational health practitioners or accident and health insurances. The stakeholders can employ our work for the development of promoting health and preventing interventions. Identified occupational risk factors of this review offer initial ideas for the development of preventing measures. A good ergonomic design of the dental workplace is especially essential to reduce awkward working postures during clinical practice and administrative work. Therefore, further research is needed on possible ergonomic and organizational measures to reduce musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals for the long term.

In sum, this review indicates that many studies in Western countries focused on the prevalence and occupational risk factors of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals. But there is still no current study from Germany. More longitudinal studies examining the etiology of musculoskeletal diseases and pain among dental professionals are essential.

Supporting information

(247 KB PDF).

(PDF)

(309 KB PDF).

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors address special thanks to the supervisory board of the Institution for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention in the Health and Welfare Services (BGW) for the encouragement of this study. The supervisory board of the BGW supported the idea to perform this review.

Abbreviations

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- BGW

Institution for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention in the Health and Welfare Services

- CI

confidence interval

- CTS

carpal tunnel syndrome

- LB

lower back

- LH

left hand

- MSDs/MSP

musculoskeletal diseases/musculoskeletal pain

- n/a

not applicable

- ns

not significant

- OR

odds ratio

- PEOS

population exposure, outcome, study design

- PRISMA

preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- ref

reference group

- RH

right hand

- TMD

temporomandibular disorders

- TMJ

temporomandibular joint

- UB

upper back

- UKE

University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf

- USA

United States of America

- VPT

vibrotactile perception thresholds

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

No special funding was received for this study. However, the Competence Center for Epidemiology and Health Services Research for Healthcare Professionals (CVcare) of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) receives an unrestricted fund from the Institution for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention in the Health and Welfare Services (BGW) on an annual basis to maintain the working group at the UKE. The funder played no role in study design, data collection and analyses, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The BGW is not responsible for the contents of the present review.

References

- 1.Aljanakh M, Shaikh S, Siddiqui AA, Al-Mansour M, Hassan SS. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dentists in the Ha’il Region of Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2015; 35 (6): 456–461. 10.5144/0256-4947.2015.456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aminian O, Banafsheh Alemohammad Z, Sadeghniiat-Haghighi K. Musculoskeletal disorders in female dentists and pharmacists: a cross-sectional study. Acta Med Iranica. 2012; 50 (9): 635–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nermin Y. Musculoskeletal disorders (Msds) and dental practice. Part 1. General information-terminology, aetiology, work-relatedness, magnitude of the problem, and prevention. Int Dent J. 2006; 56 (6): 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanc D, Farre P, Hamel O. Variability of musculoskeletal strain on dentists: an electromyographic and goniometric study. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2014; 20 (2): 295–307. 10.1080/10803548.2014.11077044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aminian O, Alemohammad ZB, Hosseini MH. Neck and upper extremity symptoms among male dentists and pharmacists. Work. 2015; 51 (4): 863–868. 10.3233/WOR-141969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stahl T. Krankheitskosten 2015 nach Krankheiten. 2017; Available from: https://www.destatis.de/DE/PresseService/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2017/09/PD17_347_236.html. Accessed 29 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayers KMS, Thomson WM, Newton JT, Morgaine KC, Rich AM. Self-reported occupational health of general dental practitioners. Occup Med. 2009; 59 (3): 142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho Kihun, Cho Hwi-Young, Han Gyeong-Soon. Risk factors associated with musculoskeletal symptoms in Korean dental practitioners. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016; 28 (1): 56–62. 10.1589/jpts.28.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes M, Cockrell D, Smith. A systematic review of musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009; 7 (3): 159–165. 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2009.00395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000; 283 (15): 2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Sys Rev. 2015; 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grifka J, Linhardt O, Liebers F. Mehrstufendiagnostik von Muskel-Skelett-Erkrankungen in der arbeitsmedizinischen Praxis. 2005; Available from: https://www.baua.de/DE/Angebote/Publikationen/Schriftenreihe/Sonderschriften/S62.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1. Accessed 13 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villa-Forte A. Tests for Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2018; Available from: https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/bone,-joint,-and-muscle-disorders/diagnosis-of-musculoskeletal-disorders/tests-for-musculoskeletal-disorders. Accessed 28 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gijbels F, Jacobs R, Princen K, Nackaerts O, Debruyne F. Potential occupational health problems for dentists in Flanders, Belgium. Clin Oral Investig. 2006; 10 (1): 8–16. 10.1007/s00784-005-0003-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner RA, Franzblau A, Gell N, Hamann C, Rodgers PA, Caruso TJ, Perry F et al. Prevalence of upper extremity symptoms and disorders among dental and dental hygiene students. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2005; 33 (2): 123–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pejčić N, Petrović V, Marković D, Miličić B, Dimitrijević II et al. Assessment of risk factors and preventive measures and their relations to work-related musculoskeletal pain among dentists. Work. 2017; 57 (4): 573–593. 10.3233/WOR-172588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vodanović M, Sović S, Galić I. Occupational health problems among dentists in Croatia. Acta stomatologica Croatica. 2016; 50 (4): 310–320. 10.15644/asc50/4/4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ariens GA, van Mechelen W, Bongers PM, Bouter LM, van der Wal G. Physical risk factors for neck pain. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000; 26 (1): 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ariens GA, van Mechelen W, Bongers PM, Bouter LM, van der Wal G. Psychosocial risk factors for neck pain: a systematic review. Am J Indus Med. 2001; 39 (2): 180–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Rijn RM, Huisstede BM, Koes BW, Burdorf A. Associations between work-related factors and the carpal tunnel syndrome—a systematic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2009; 35 (1): 19–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neyeloff JL, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB. Meta-analyses and forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2012; 5 (1): 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003; 327 (7414): 557–560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harutunian K, Gargallo-Albiol J, Figueiredo R, Gay-Escoda C. Ergonomics and musculoskeletal pain among postgraduate students and faculty members of the School of Dentistry of the University of Barcelona (Spain). A cross-sectional study. Medicina oral, patología oral y cirugía bucal. 2011; 16 (3): 425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaffer SW, Moore R, Foo S, Henry N, Moore JH et al. Clinical and electrodiagnostic abnormalities of the median nerve in US Army dental assistants at the onset of training. US Army Med Dep. 2012; 72–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding H, Solovieva S, Vehmas T, Riihimaki H, Leino-Arjas P. Finger joint pain in relation to radiographic osteoarthritis and joint location—a study of middle-aged female dentists and teachers. Rheumatol. 2007; 46 (9): 1502–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding H, Solovieva S, Leino-Arjas P. Determinants of incident and persistent finger joint pain during a five-year follow up among female dentists and teachers. Arthritis Care Res. 2011; 63 (5): 702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes MJ, Taylor JA, Smith DR. Predictors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dental hygienists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012; 10 (4): 265–269. 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2011.00536.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rising DW, Bennett BC, Hursh K, Plesh O. Reports of body pain in a dental student population. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005; 136 (1): 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solovieva S, Vehmas T, Riihimaki H, Takala EP, Murtomaa H et al. Finger osteoarthritis and differences in dental work tasks. J Dent Res. 2006; 85 (4): 344–348. 10.1177/154405910608500412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren N. Causes of musculoskeletal disorders in dental hygienists and dental hygiene students: a study of combined biomechanical and psychosocial risk factors. Work. 2010; 35 (4): 441–454. 10.3233/WOR-2010-0981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marklund S, Wanman A. Risk factors associated with incidence and persistence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. Acta Odontol Scand. 2010; 68 (5): 289–299. 10.3109/00016357.2010.494621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marklund S, Wiesinger B, Wanman A. Reciprocal influence on the incidence of symptoms in trigeminally and spinally innervated areas. Eur J Pain. 2010a; 14 (4): 366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abou-Atme YS, Zawawi KH, Melis M. Prevalence, intensity, and correlation of different TMJ symptoms in Lebanese and Italian subpopulations. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006; 7 (4): 71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayes MJ, Smith DR, Cockrell D. Prevalence and correlates of musculoskeletal disorders among Australian dental hygiene students. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009a; 7 (3): 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayes MJ, Smith DR, Taylor JA. Musculoskeletal disorders and symptom severity among Australian dental hygienists. BMC Res Notes. 2013; 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodacova L, Sustova Z, Cermakova E, Kapitan M, Smejkalova J. Self-reported risk factors related to the most frequent musculoskeletal complaints among Czech dentists. Indus Health. 2015; 53 (1): 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humann P, Rowe DJ. Relationship of musculoskeletal disorder pain to patterns of clinical care in California dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2015; 89 (5): 305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kierklo A, Kobus A, Jaworska M, Botulinski B. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dentists—a questionnaire survey. AAEM. 2011; 18 (1): 79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulcu DG, Gulsen G, Altunok TC, Kucukoglu D, Naderi S. Neck and low back pain among dentistry staff. Turk J Rheumatol. 2010; 25 (3): 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leggat PA, Smith DR. Musculoskeletal disorders self-reported by dentists in Queensland, Australia. Austr Dent J. 2006; 51 (4): 324–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindfors P, Thiele U von, Lundberg U. Work characteristics and upper extremity disorders in female dental health workers. J Occup Health. 2006; 48 (3): 192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palliser CR, Firth HM, Feyer AM, Paulin SM. Musculoskeletal discomfort and work-related stress in New Zealand dentists. Work Stress. 2005; 19 (4): 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peros K, Vodanovic M, Mestrovic S, Rosin-Grget K, Valic M. Physical fitness course in the dental curriculum and prevention of low back pain. J Dent Educ. 2011; 75 (6): 761–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puriene A, Aleksejuniene J, Petrauskiene J, Balciuniene I, Janulyte V. Self-reported occupational health issues among Lithuanian dentists. Indus Health. 2008; 46 (4): 369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakzewski L, Naser-ud-Din S. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Australian dentists and orthodontists: Risk assessment and prevention. Work. 2015; 52 (3): 559–579. 10.3233/WOR-152122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samotoi A, Moffat SM, Thomson WM. Musculoskeletal symptoms in New Zealand dental therapists: prevalence and associated disability. NZ Dent J. 2008; 104 (2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sustova Z, Hodacova L, Kapitan M. The prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dentists in the Czech Republic. Acta Med. 2013; 56 (4): 150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thornton LJ, Barr AE, Stuart-Buttle C, Gaughan JP, Wilson ER et al. Perceived musculoskeletal symptoms among dental students in the clinic work environment. Ergonomics. 2008; 51 (4): 573–586. 10.1080/00140130701728277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yee T, Crawford L, Harber P. Work environment of dental hygienists. J Occup Environ Med. 2005; 47 (6): 633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zitzmann NU, Chen MD, Zenhausern R. Frequency and manifestations of back pain in the dental profession. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2008; 118 (7): 610–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]