Heart failure is a constellation of symptoms and signs of fluid retention caused by abnormalities in the pericardium, myocardium, endocardium, heart valves, or coronary vessels. It is classified by the presence of an ejection fraction (EF) that is reduced (≤40%), borderline (41%–49%), or preserved (≥50%), and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality for both women and men.1 It remains a leading cause of hospitalization and accounts for about 8% of all cardiovascular death.2 There are many sex differences and this article focuses on those related to epidemiology, cause, diagnosis, medical therapy, and cardiac rehabilitation among heart failure patients with reduced EF.

EPIDEMIOLOGY, PROGNOSIS, AND CAUSES

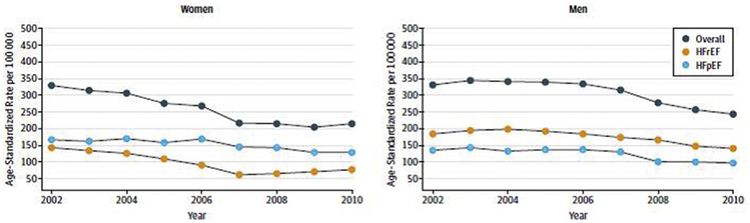

Heart failure affects approximately 6.5 million adults in the United States, and nearly 50% of these are women. In 2013, approximately 500,000 new cases of heart failure occurred among women 55 years or older, with a similar but lower incidence among men.2 Based on Olmsted County, Minnesota, data, the incidence of heart failure has declined over the years with a greater reduction in women with heart failure and reduced EF compared with men with heart failure and reduced or preserved EF (Fig. 1).3 The prevalence of heart failure increases with age for both sexes with men more likely than women to have heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF). HFrEF is defined as an EF less than or equal to 40% and occurs in approximately 46% of those hospitalized with heart failure.4 Compared with men, women hospitalized with HFrEF are more likely to be older, have hypertension and valvular disease, and less likely to have coronary artery disease or peripheral vascular disease.5 There are no significant sex differences in in-hospital mortality among patients with HFrEF (2.69% women vs 2.89% men, P = .20) and women and men share many risk factors, including age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and history of renal failure or dialysis.6 Approximately 40% of the patients hospitalized with HFrEF are women, and 5-year mortality for women and men with HFrEF is similar to heart failure patients with preserved EF (75.3% vs 75.7%, respectively).4

Fig. 1.

Sex differences in incidence of heart failure with reduced EF (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved EF (HFpEF). Data regarding the incidence of age-adjusted heart failure in Olmsted County, Minnesota, between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2010, were stratified by sex and EF. The incidence of heart failure declined for both women and men but was greater in women with HFrEF compared with men with HFrEF or HFpEF. (From Gerber Y, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. A contemporary appraisal of the heart failure epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(6):996–1004; with permission.)

DIAGNOSIS

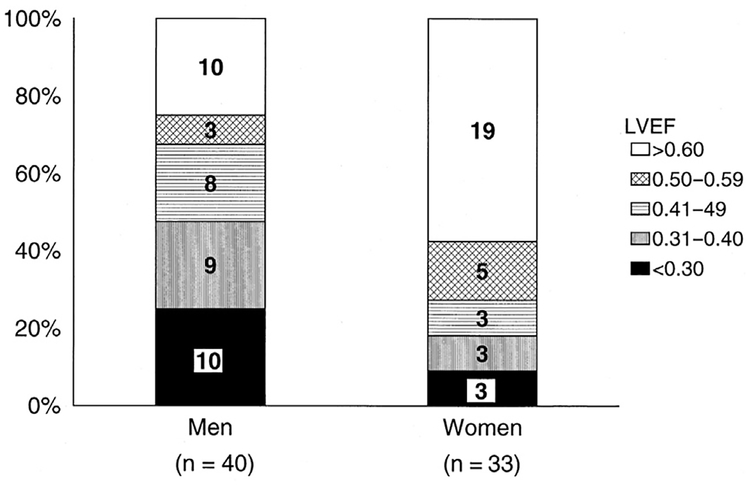

The diagnosis of HFrEF is defined by an EF less than or equal to 40% by imaging. According to the American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association heart failure guidelines, a 2-dimensional echocardiogram with Doppler should be performed on all heart failure patients to evaluate ventricular function, cardiac size, wall thickness and motion, and valve function during the initial evaluation and subsequent visits when there are changes in the clinical status or therapy expected to improve ventricular function. Cardiac MRI, cardiovascular computed tomography, nuclear stress testing, or cardiac catheterization may also be considered.1 Based on population studies, including data from the Framingham Heart Study, HFrEF is less likely in women (Fig. 2).7 In a recently published article by Shah and colleagues4 involving more than 254 hospitals, women represented about 40% of patients hospitalized with HFrEF. The symptoms and signs of heart failure are similar between women and men; however, women with HFrEF are more likely than men to have dyspnea, third heart sound (S3) gallop, jugular venous distension, and leg edema.8

Fig. 2.

Sex differences in left ventricular EF (LVEF) among subjects from the Framingham Heart Study who developed heart failure (N = 73). (From Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, et al. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 999;33(7):1948–50; with permission.)

BIOMARKERS

Biomarkers such as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) are useful to support clinical evaluation, diagnosis, and prognosis of heart failure, especially in cases in which uncertainty is present.1 Women tend to have higher natriuretic peptide levels when compared with men with decompensated heart failure, including those with HFrEF (median BNP in women 1259 vs men 1113 pg/mL, P<.001). BNP is predictive of in-hospital mortality for both women and men almost regardless of the EF (Table 1).5 The utility of serial measurements of natriuretic peptides can be helpful to guide optimal dosing of medical therapy with neurohormonal blocking agents, although sex-specific data are lacking.1 An elevated troponin in the setting of chronic HFrEF portrays a poor prognosis for both women and men, especially when there is no significant coronary artery disease.9 Newer biomarkers, such as soluble suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (ST2) and galactin-3, may have further potential for diagnosis, evaluation, and prognostic value; however, studies are still needed before routine clinical application.10,11

Table 1.

Sex differences in adjusted odds ratio for log brain natriuretic peptide and in-hospital mortality stratified by ejection fraction

| Model 1, Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI), P Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | All Patients (N = 98,579) | EF <40% Female (n = 17,262) | EF <40% Male (n = 29,171) | EF 40%–49% Female (n = 6666) | EF 40%–49% Male (n = 7085) | EF >50% Female (n = 24,907) | EF >50% Male (n = 13,488) |

| Unadjusted | 1.45 (1.32–1.58), P<.0001 |

1.51 (1.23–1.86), P = .0001 |

1.48 (1.27–1.74), P<.0001 |

1.35 (1.04–1.75), P = .0265 |

1.28 (1.05–1.56), P = .0163 |

1.53 (1.38–1.71), P<.0001 |

1.32 (1.16–1.52), P<.001 |

| Multivariate adjusted | 1.34 (1.14–1.58), P<.0004 |

1.25 (0.97–1.61), P = .0876 |

1.28 (1.05–1.56), P = .0161 |

1.20 (0.84–1.71), P = .3231 |

1.18 (0.92–1.52), P = .1857 |

1.52 (1.34–1.71), P<.0001 |

1.25 (1.02–1.52), P = .0291 |

From Hsich EM, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Hernandez AF, et al. Relationship between sex, ejection fraction, and B-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients hospitalized with heart failure and associations with inhospital outcomes: findings from the get with the guideline-heart failure registry. Am Heart J 2013;16(6):1063–9; with permission.

MEDICAL THERAPY

Over the last few decades, many HFrEF therapies have been proven to improve outcomes. Among the established medical therapies for HFrEF, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, aldosterone antagonists, and hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate have been shown in randomized controlled trials to improve symptoms, reduce burden of hospitalization, and decrease mortality.1 Newer agents, such as angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor and the hyper-polarization channel blocker ivabradine, have recently been proven to be beneficial and added to the treatment guidelines for HFrEF.12

Currently, there are no HFrEF sex-specific guidelines because women have been underrep-resented in clinical trials and sex-specific data were rarely prospectively analyzed. Female participation in landmark trials ranged from 0% to 40% with an average of about 20% women (Table 2).13 One HFrEF trial to date, the Beta-Blocker Evaluation of Survival Trial (BEST),14 has prospectively stratified patients by sex. All other studies either analyzed data retrospectively or via post hoc analysis.13 This article summarizes the sex-specific data for all guideline HFrEF medical therapy based on the limited data available.

Table 2.

Representation of women in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction clinical trials

| Medical Therapy for HFrEF | Name | Trial (% Women, Number Women) |

|---|---|---|

| Beta blockers | Carvedilol | COPERNICUS22 (20%, 469) |

| US Carvedilol Study21 (23%, 256) | ||

| Metoprolol succinate | MERIT-HF24 (23%, 898) | |

| Bisoprolol | CIBIS II23 (19%, 515) | |

| ACEI | Captopril, enalapril, ramipril, trandolapril, zofenopril | Meta-analysis17 (19%, 2373) |

| Captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, quinapril, ramipril | Meta-analysis16 (23%, 1587) | |

| ARB | Valsartan | Val-HeFT19 (20%, 1003) |

| Losartan | ELITE II42 (31%, 966) | |

| Candesartan | CHARM—low EF18 (26%, 1188) | |

| Aldosterone antagonist or MRA | Eplerenone | EPHESUS27 (29%, 1918) |

| EMPHASIS-HF26 (22%, 610) | ||

| Spironolactone | RALES25 (27%, 446) | |

| Hydralazine or isosorbide dinitrate | V-HeFT I28 (0%, 0) | |

| V-HeFT II29 (0%, 0) | ||

| A-HeFT30 (40%, 420) | ||

| Digoxin | DIG33 (22%, 1520) | |

| Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor | Sacubitril-valsartan | PARADIGM-HF34 (22%, 1832) |

| Ivabradine | SHIFT35 (23%, 1535) |

Abbreviations: A-HeFT, African-American Heart Failure Trial; CHARM, Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Mortality and Morbidity; CIBIS, Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study; COPERNICUS, Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival Study; DIG, Digitalis Investigation Group; ELITE, Evaluation of Losartan in the Elderly; ELITE EMPHASIS-HF, Eplere-none in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure; EPHESUS, Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study; MERIT-HF, Metoprolol Extended-Release Randomized Intervention Trial in Heart Failure; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; PARADIGM-HF, Prospective Comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure; RALES, Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study; SHIFT, Systolic Heart Failure Treatment with the If Inhibitor Ivabradine Trial; V-HeFT, Valsartan Heart Failure Trial.

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

ACEIs have been shown to be beneficial since the late 1980s when enalapril improved survival in patients with severe congestive heart failure when compared with placebo in the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS) trial.15 ACEIs are recommended for all patients with HFrEF.1 However, the benefits in women are unclear because too few women participated in the landmark trials. Two different large meta-analyses with more than 1500 women showed a trend toward improvement in survival and reduction in hospitalizations for women with HFrEF but no clear benefit because the 95% confidence intervals were wide and crossed 1.0.16,17

Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

ARBs are often used in ACEI-intolerant HFrEF patients, and deemed to have similar morbidity and mortality benefits.12 Sex-specific data for ARBs are limited, with candesartan and valsartan appearing beneficial in women with HFrEF. Pooled data from 2 Candesartan in Heart Failure Assessment of Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) trials (CHARM-Alternative to an ACEI and CHARM-Added to an ACEI) showed reduction of the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization for the 592 women with symptomatic heart failure and left ventricular EF less than or equal to 40% treated with candesartan when compared with the 596 women in the control group.18 In the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT), valsartan was compared with placebo for patients with symptomatic HFrEF (EF ≤40%). Although valsartan did not significantly reduce mortality among women (N = 1003 women total in trial), it did reduce heart failure hospitalization with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.74 (95% CI 0.55–0.98).13,19

Beta Blockers

Three beta-adrenergic receptor blockers (carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, and bisoprolol) are recommended and have been shown to improve survival in HFrEF with a relative risk reduction of mortality by about 30%.1,20 Carvedilol is a nonselective, β-blocker with α-blocking and antioxidant properties. Trials such as the US Carvedilol Heart Failure Study and the Carvedilol Prospective Randomized Cumulative Survival Study (COPERNICUS) demonstrated benefit of carvedilol in women with symptomatic heart failure.21,22 In the US Carvedilol Heart Failure Study, there were 256 women with HFrEF (EF ≤35%) and those treated with carvedilol had reduced mortality (HR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07–0.69).21 In the COPERNICUS trial, which determined the effect of carvedilol in severely symptomatic patients with an EF less than 25%, carvedilol reduced the combined endpoint of death or hospitalization among the 469 women studied, mostly driven by a reduction in hospitalization.22 Bisoprolol and metoprolol succinate are β−1 selective adrenergic antagonists that have proven benefit in HFrEF. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval was only for metoprolol succinate because bisoprolol was not studied in the United States. In the European Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study (CIBIS II), bisoprolol improved all-cause mortality among the women participants (N = 515 women) when compared with controls.23 In the Metoprolol Extended-Release Randomized Intervention Trial in Heart Failure (MERIT-HF), metoprolol succinate reduced heart failure hospitalization by 42% among women with symptomatic heart failure and an EF less than or equal to 40%, and by 72% in women with an EF less than 25%.24

Aldosterone Antagonists

Aldosterone antagonists are recommended for all HFrEF with symptoms and an EF less than or equal to 35% or an EF less than or equal to 40% after an acute myocardial infarction.1 These drugs are quite favorable for women based on subgroup post hoc analysis as demonstrated by the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES), which included 446 women25; the Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure (EMPHASIS-HF), which included 516 women26; and the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (EPHESUS), which included 1918 women.27 The RALES trial compared aldosterone to placebo in both ischemic and nonischemic heart failure patients with moderate-severe symptoms (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class III-IV) and an EF less than or equal to 35%, and demonstrated that women taking aldosterone had a reduction in mortality.25 The EMPHASIS-HF study compared ischemic and nonischemic heart failure patients with mild symptoms (NYHA class II) and an EF less than 35% to eplerenone versus placebo. Among the women participants, the combined endpoint of mortality and heart failure hospitalization was reduced in those taking the drug.26 The EPHESUS trial studied the effects of eplerenone among patients with an acute myocardial infarction and an EF less than or equal to 40%, and found women taking eplerenone had a reduction in mortality.27

Hydralazine-Isosorbide Dinitrate

The combination of hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate in those who cannot tolerate an ACEI nor ARB was found to improve survival; however, this was only studied in men.28,29 The only hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate study that included women was the African-American Heart Failure Trial (A-HEFT), which was notable for enrolling 41% women (N = 420 women) with moderate-severe heart failure (NYHA class III-IV). This study demonstrated that the combination therapy improved survival, quality of life, and reduced hospitalization for African American women when added to ACEI or ARB and beta blockers.30

Digoxin

Since being first described in the 1700s to treat heart failure,31 digoxin was commonly used and can be beneficial in reducing heart failure hospitalizations.1 However, in the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, the post hoc subgroup analysis demonstrated increased mortality in women with an adjusted HR of 1.23 (95% CI 1.02–1.47).32 Most likely, this was due to increased serum levels of 1.2 to 2.0 ng/mL, with improved survival between 0.5 to 0.9 ng/mL for both sexes, in a retrospective analysis.33 Given the lack of survival benefit with digoxin and the multiple benefits of other therapies, recommendations are to optimize other therapies before adding digoxin as current care.

Sacubitril-Valsartan

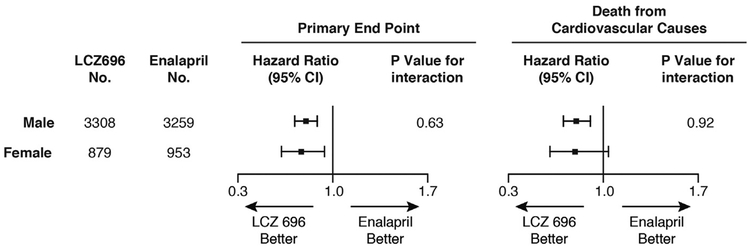

In 2014, the Prospective Comparison of ARNI [angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor] with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure (PARADIGM-HF) trial results were published. It compared a neprilysin inhibitor (sacubitril) combined with an ARB (valsartan) versus an ACEI (enalapril) in symptomatic heart failure patients (NYHA class II-IV) with an EF less than or equal to 40% (criteria amendment on Dec 15, 2010, changed to EF ≤35%). The PARADIGM-HF trial included 21% women (N = 1832) and demonstrated a reduction in the primary combined endpoint of cardiovascular mortality and heart failure hospitalization for women taking an ARNI when compared with women taking an ACEI. This benefit in women was driven by hospitalizations and not mortality (Fig. 3), raising the question of whether the neprilysin inhibitor added to the known benefit of valsartan to reduce hospitalization in women.34 The ideal control for PARADIGM-HF would have been valsartan so that the effect of adding the neprilysin inhibitor could have been determined because the benefits of ACEI in women remain unclear.17

Fig. 3.

Sex differences in outcome among HFrEF subjects in PARADIGM-HF taking sacubitril-valsartan (LCZ696) versus control therapy (enalapril). The combined primary endpoint was mortality and heart failure hospitalization. (Adapted from McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371(11):993–1004; with permission.)

Ivabradine

Ivabradine was approved by the FDA in 2015 after the Systolic Heart Failure Treatment with the If Inhibitor Ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) trial in Europe demonstrated significant reduction in hospitalization for worsening heart failure. The trial included 23% women (N = 1535) in sinus rhythm who had chronic symptomatic systolic heart failure (NYHA class II-IV) with a resting heart rate greater than or equal to 70 beats per minute and an EF of less than or equal to 35%. A subgroup analysis on sex demonstrated similar effectiveness in women when compared with men.35

Antiplatelet Agents and Anticoagulation

The Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOVLD) trial demonstrated that women had an increased risk of thromboembolic events compared with men, 2.4 events per 100 participant-years of follow-up versus 1.8 events per 100 participant-years of follow-up. The trial was composed of 14% women (N = 921) with an EF less than or equal to 35%, and it excluded those with atrial fibrillation. A multivariable analysis noted sex differences in risk factors with a lower EF associated with higher risk of thromboembolic events in women but not in men. Usage of antiplatelet therapy was associated with a lower risk of thromboembolic events in both women and men although anticoagulant therapy was not. There were also sex differences in the type of thromboembolic events, with women having a higher percentage of pulmonary embolic events than men (24% vs 14%, P = .1).36 To further explore prevention of thromboembolic events, the Warfarin versus Aspirin in Reduced Cardiac Ejection Fraction (WARCEF) trial was designed. The results showed no difference between agents in the risk of ischemic stroke, intra-cerebral hemorrhage, or death from any cause. The data were never analyzed for sex differences but did include 20% women (N = 461) with symptomatic HFrEF.37

Cardiac Rehabilitation

The Heart Failure: A Controlled Trial Investigating Outcomes of Exercise Training (HF-ACTION) trial included 28% women (N = 661) with symptomatic heart failure and an EF less than or equal to 35%. After adjustment for prognostic predictors, it demonstrated modest significant reductions in all-cause mortality or hospitalization, as well as in cardiovascular mortality or heart failure hospitalizations. Based on subgroup post hoc analysis, women benefited from an exercise training program and possibly more than men.38

CardioMEMS

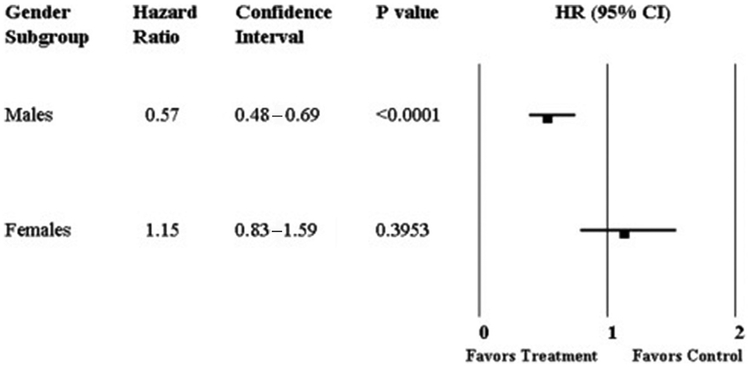

The CardioMEMS (St Jude Medical-St Paul Tech Center, St. Paul, MN) is a device permanently implanted in the pulmonary artery to monitor pulmonary pressures to guide medical therapy for acute decompensated heart failure. The utility of the device was studied in the CardioMEMS Heart Sensor Allows Monitoring of Pressure to Improve Outcomes in NYHA Class III Patients (CHAMPION) study. CHAMPION was a single-blinded randomized controlled trial that included 78% (N = 431) HFrEF patients.39 In a subgroup analysis of those with HFrEF that included 24% women (n = 111), treatment with the CardioMEMS demonstrated a 43% risk reduction in heart failure hospitalization and a 57% reduction in mortality.40 The CHAMPION trial has been widely criticized for many reasons, including sex differences in outcomes. The FDA reviewed the analysis and did not consider the statistical methods adequate to account for the greater than expected variability in the primary endpoint of hospitalizations. Additionally, sex-specific data for the entire cohort (74% of total women were HFrEF), showed that the CardioMEMS reduced heart failure hospitalization in men but not women (Fig. 4), although the sponsors stated that the study was inadequately powered to detect sex differences due to the small number of events in women.41

Fig. 4.

Sex differences in HR for heart failure hospitalization among subjects with and without CardioMEMS. (From Loh JP, Barbash IM, Waksman R. Overview of the 2011 Food and Drug Administration Circulatory System Devices Panel of the Medical Devices Advisory Committee Meeting on the CardioMEMS Champion Heart Failure Monitoring System. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61(15):1571–5; with permission.)

SUMMARY

HFrEF is less common in women than men but with several sex differences in the underlying disease. Women with HFrEF are more likely than men to have hypertension and valvular disease, and less likely to have coronary artery disease. In-hospital mortality is similar and low; however, when hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure, the 5-year mortality rate is very high for both men and women. Natriuretic peptide serum levels are higher in women with decompensated heart failure than men but yield similar prognostic risk for in-hospital mortality. The CardioMEMS is used to monitor acute decompensated heart failure events and guide therapy, although their utility in women remains unclear based on information from the CHAMPION trial. There remains no sex-specific guideline therapy for HFrEF because women were underrepresented in clinical trials and studies were never designed to prospectively study sex differences. Based on post hoc analyses or retrospective studies, β-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, ARBs, and ivabradine seem beneficial in women with HFrEF. The combination of hydralazine and isosorbide was studied in black women with HFrEF and found to reduce mortality, reduce hospitalizations, and improve quality of life. More studies are needed and should be prospectively designed to study sex differences to better understand the effects of drugs and technology on women with HFrEF.

KEY POINTS.

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) affects more men than women but has significant morbidity and mortality for all patients.

There are sex differences in the underlying disease causing HFrEF, with women more likely to have hypertension and valvular disease, and less likely to have coronary artery disease, than men.

There are no sex-specific heart failure guidelines for medical management because women were underrepresented in clinical trials and the landmark trials were not prospectively designed to study sex differences.

Post hoc and retrospective analysis suggest that β-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, angiotensin receptor blockers, and ivabradine are beneficial in all women with HFrEF, and the combination of hydralazine and isosorbide is beneficial in black women with HFrEF.

Post hoc analysis suggests that sacubitril-valsartan is better than enalapril for women with HFrEF but it remains unclear if the benefit is due to valsartan or the combination of valsartan and sacubitril.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Eileen Hsich is supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health under Award Number R01HL141892. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013;128(16): e240–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135(10):e146–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerber Y, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. A contemporary appraisal of the heart failure epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(6):996–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah KS, Xu H, Matsouaka RA, et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70(20):2476–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsich EM, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Hernandez AF, et al. Relationship between sex, ejection fraction, and B-type natriuretic peptide levels in patients hospitalized with heart failure and associations with inhospital outcomes: findings from the Get With The Guideline-Heart Failure Registry. Am Heart J 2013; 166(6):1063–71.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsich EM, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Hernandez AF, et al. Sex differences in in-hospital mortality in acute de-compensated heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Am Heart J 2012;163(3): 430–7, 437.e1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, et al. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33(7):1948–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnstone D, Limacher M, Rousseau M, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). Am J Cardiol 1992; 70(9):894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egstrup M, Schou M, Tuxen CD, et al. Prediction of outcome by highly sensitive troponin T in outpatients with chronic systolic left ventricular heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2012;110(4):552–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow SL, Maisel AS, Anand I, et al. Role of bio-markers for the prevention, assessment, and management of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135(22):e1054–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motiwala SR, Sarma A, Januzzi JL, et al. Biomarkers in ACS and heart failure: should men and women be interpreted differently? Clin Chem 2014;60(1):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update on new pharmacological therapy for heart failure: an update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2016;134(13):e282–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsich EM, Pina IL. Heart failure in women: a need for prospective data. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54(6):491–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghali JK, Krause-Steinrauf HJ, Adams KF, et al. Gender differences in advanced heart failure: insights from the BEST study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42(12):2128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure. Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 1987;316(23):1429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garg R, Yusuf S. Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. Collaborative Group on ACE Inhibitor Trials. JAMA 1995;273(18):1450–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shekelle PG, Rich MW, Morton SC, et al. Efficacy of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and beta-blockers in the management of left ventricular systolic dysfunction according to race, gender, and diabetic status: a meta-analysis of major clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41(9):1529–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young JB, Dunlap ME, Pfeffer MA, et al. Mortality and morbidity reduction with Candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction: results of the CHARM low-left ventricular ejection fraction trials. Circulation 2004; 110(17):2618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohn JN, Tognoni G. A randomized trial of the angiotensin-receptor blocker valsartan in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345(23):1667–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fonarow GC, Yancy CW, Hernandez AF, et al. Potential impact of optimal implementation of evidence-based heart failure therapies on mortality. Am Heart J 2011;161(6):1024–30.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Packer M, Bristow MR, Cohn JN, et al. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. N Engl J Med 1996;334(21):1349–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packer M, Fowler MB, Roecker EB, et al. Effect of carvedilol on the morbidity of patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of the carvedilol prospective randomized cumulative survival (COPERNICUS) study. Circulation 2002;106(17):2194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon T, Mary-Krause M, Funck-Brentano C, et al. Sex differences in the prognosis of congestive heart failure: results from the Cardiac Insufficiency Bisoprolol Study (CIBIS II). Circulation 2001;103(3): 375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghali JK, Pina IL, Gottlieb SS, et al. Metoprolol CR/XL in female patients with heart failure: analysis of the experience in Metoprolol Extended-Release Randomized Intervention Trial in Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Circulation 2002;105(13):1585–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999;341(10):709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med 2011;364(1):11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;348(14):1309–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohn JN, Archibald DG, Ziesche S, et al. Effect of vasodilator therapy on mortality in chronic congestive heart failure. Results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med 1986; 314(24):1547–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohn JN, Johnson G, Ziesche S, et al. A comparison of enalapril with hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate in the treatment of chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991;325(5):303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor AL, Lindenfeld J, Ziesche S, et al. Outcomes by gender in the African-American Heart Failure Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48(11):2263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodsley J, Elmsly P, Leigh Sotheby Medical transactions, Vol. 3 College of Physicians in London; 1785. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rathore SS, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. Sex-based differences in the effect of digoxin for the treatment of heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002;347(18): 1403–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams KF Jr, Patterson JH, Gattis WA, et al. Relationship of serum digoxin concentration to mortality and morbidity in women in the digitalis investigation group trial: a retrospective analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46(3):497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371(11):993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2010;376(9744):875–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dries DL, Rosenberg YD, Waclawiw MA, et al. Ejection fraction and risk of thromboembolic events in patients with systolic dysfunction and sinus rhythm: evidence for gender differences in the Studies of Left Ventricular dysfunction trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;29(5):1074–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Homma S, Thompson JL, Pullicino PM, et al. Warfarin and aspirin in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm. N Engl J Med 2012;366(20): 1859–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, et al. Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301(14):1439–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377(9766):658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Givertz MM, Stevenson LW, Costanzo MR, et al. Pulmonary artery pressure-guided management of patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70(15): 1875–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loh JP, Barbash IM, Waksman R. Overview of the 2011 Food and drug administration circulatory system devices panel of the medical devices advisory committee meeting on the CardioMEMS champion heart failure monitoring system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61(15):1571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Segal R, et al. Effect of losartan compared with captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: randomised trial—the Losartan Heart Failure Survival Study ELITE II. Lancet 2000;355(9215):1582–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]