Abstract

Despite continuity in the desire for sex and partnership, many older adults experience a lack of intimacy in late life. The use of assisted living is a complicating factor for understanding issues of partnership, sex, and intimacy for older adults. Using in-depth interviews with 23 assisted living residents and grounded theory methods, we examined how residents negotiate a lack of intimacy in assisted living. The process of negotiation entailed three factors: desire, barriers, and strategies. Although some residents continued to desire intimacy, there was a marked absence of dating or intimacy in our study sites. Findings highlight unique barriers to acting on desire and the strategies residents used as aligning actions between desire and barriers. This research expands previous studies of sexuality and older adults by examining the complex ways in which they balanced desire and barriers through the use of strategies within the assisted living environment.

Images of dating in late life tend to be fraught with age stereotypes and contradictions. Obvious and subtle messages suggest that sex is normal and desirable for healthy, young adults, but that older adults are asexual and no longer interested (Walz, 2002). These messages exist in contrast to representations of sexually active third-agers (Vares, 2009). As with all stereotypes the actual experience of sex and intimacy in late life is more complex and variable (Lindau et al., 2007). While younger adults tend to engage in sexual behaviors more often than older adults, the majority of older adults remain interested in sex and value it as an important component of quality of life (DeLamater, 2012; DeLamater & Sill, 2005; Lindau et al., 2007; Waite, Laumann, Das, & Schumm, 2009). However, the opportunity and desire for sex and intimacy in later life vary depending on access to intimate partnerships, health of self and partner, living arrangements, and life course experiences (Burgess, 2004; Carpenter, 2010; Fileborn, Thorpe, Hawkes, Minichiello, & Pitts, 2015).

A decline in the frequency of sexual activity and interest in sex is not solely influenced by chronological aging but is also dependent on one’s social circumstances (Karraker & DeLamater, 2013; Lindau et al., 2007). Thus, desire for sex and intimacy does not always align with opportunity. Other predictors of a decrease in sexual activity include a lack of available partners (Ginsberg, Pomerantz, & Kramer-Feeley, 2005; Gott & Hinchliff, 2003; Lindau et al., 2007), health status (Karraker & DeLamater, 2013; Laumann & Waite, 2008; Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010; Syme, Klonoff, Macera, & Brodine, 2012), and the age and health status of one’s partner (Gott & Hinchliff, 2003; Karraker & DeLamater, 2013; Lindau et al., 2007; Lodge & Umberson, 2012; Syme et al., 2012). Sexual desire and activity in late life may reflect earlier life patterns (Burgess, 2004; Carpenter, 2010). Additionally, initiating dating after the death of a spouse is challenging for both men and women because of uncertainty about how to negotiate the changing landscape of dating and intimacy (Moore & Stratton, 2001; van den Hoonaard, 2001). Only about 14% of older singles are involved in dating relationships and widowed singles are less likely to date then divorced or never married older adults (Brown & Shinohara, 2013). Finally, older adults may internalize stereotypes about aging bodies, dating, intimacy, and sexuality (Clarke, 2011) and limit their pursuit of intimacy and relationships (Jen, 2017).

Sexuality in Long-Term Care

A complicating factor for understanding issues of sex and intimacy for older adults is the use of long-term care (LTC). While there is a growing body of literature addressing sexuality and aging in general, studies examining issues of sexuality and intimacy in LTC remain relatively limited, primarily focused on skilled nursing facilities, and rarely include the resident perspective (Aizenberg, Weizman, & Barak, 2002; Elias & Ryan, 2011). Most existing research focuses on general issues of sexuality in LTC (Aizenberg et al., 2002; Di Napoli, Breland, & Allen, 2013; Elias & Ryan, 2011; Mroczek, Kurpas, Gronowska, Kotwas, & Karakiewicz, 2013) or on specific issues such as barriers, attitudes and knowledge of staff, and concerns about sexual abuse and sexually inappropriate behaviors (Mahieu & Gastmans, 2015; Makimoto, Kang, Yamakawa, & Konno, 2015; Tucker, 2010). Entering a LTC setting does not automatically result in decreased interest in sex (Elias & Ryan, 2011; Mahieu & Gastmans, 2015). However, barriers to sexual expression for residents include contextual and structural barriers such as a lack of privacy, negative staff attitudes and behaviors, a focus on safety, lack of communication about sexuality, and the absence of available partners (Barmon, Burgess, Bender, & Moorhead, 2017; Elias & Ryan, 2011; Makimoto et al., 2015; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2016; Villar, Celdrán, Fabà, & Serrat, 2014), as well as individual barriers including internalized ageism, religiosity, health status, and continuing to honor marital vows (Jen, 2017; Palacios-Ceña et al., 2016). Sexually active residents report barriers to engaging in sex such as negative staff attitudes, feelings of guilt, and feeling undesirable (Langer, 2009).

Context of Assisted Living

In contrast to skilled nursing facilities, assisted living (AL) is a mid-range LTC environment which offers a more homelike atmosphere with greater opportunities for privacy and independence while providing personal care, meals, and 24-hour protective oversight (Utz, 2003). As one of the fastest growing forms of housing for older adults, there are approximately 30,200 AL communities across the United States serving over 835,2500 older adults (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016). Predominantly private-pay, these facilities traditionally cater to a financially secure, primarily White population of seniors (Feng, Fennell, Tyler, Clark, & Mor, 2011). In line with the social model of care over 90 percent of AL residents reside in private rooms or with a relative in a shared room, but share meals and activities with other residents (AAHSA et al., 2009).

Although congregate living among older adults requires social contact through common space, shared meals, and activities, this physical closeness does not guarantee social engagement (Kemp, Ball, Hollingsworth, & Perkins, 2012). Most existing research focuses on social relationships (i.e. friendships) which may or may not include intimate or dating relationships. For AL residents who have control over their living situation, such as the decision and ability to finance the move, they experience greater overall well-being and higher satisfaction with their social relationships (Burge & Street, 2010; Street & Burge, 2012). AL resident relationships can predict life satisfaction (Park, 2009) and quality of life (Ball et al., 2005; Ball et al., 2000). Yet, residents do not have an equal chance to engage in relationships. Functional and cognitive impairments limit opportunity for social relationships to develop (Dobbs et al., 2008; Iecovich & Lev-Ran, 2006; Kemp et al., 2012; Sandhu, Kemp, Ball, Burgess, & Perkins, 2013). Furthermore, these relationships are not unilateral and are not always positive or supportive (Kemp et al., 2012). Additionally, the context of AL is not fixed. AL residents are embedded in a social and institutional environment that is continually evolving (Perkins, Ball, Kemp, & Hollingsworth, 2013; Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012). These fluctuations shape residents’ experiences of AL over time and the ability to age in place.

This paper addresses the gaps in the existing literature by examining intimacy and sexuality in AL from the residents’ perspective. Using a grounded theory perspective we explore how residents negotiate sexuality and intimacy within this context. The goal of the larger study and this paper is to understand the creation of the personal and social meanings associated with intimacy, as well as the various processes that are operating in this setting.

Method

This analysis is from a larger National Institute on Aging-funded qualitative study exploring how sexuality and intimacy are negotiated in AL facilities. The larger two-year study (2009–2011) investigated how residents, family, staff, and administrators negotiate sexuality and intimacy in AL facilities. Focusing on the residents’ perspective, the goal of this analysis is to explore barriers and facilitators to resident sexual expression in AL. Using principles of grounded theory, we analyze the interviews from residents who live in AL. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Georgia State University (#H08476). The names of individuals and AL communities used throughout the manuscript are pseudonyms.

Data Collection

The setting for this study was six purposively sampled facilities that differed in size, ownership, and location (urban, suburban, exurban) with the metropolitan Atlanta area. Although the homes varied according to these factors, they were similar in other areas such as sex-ratio (predominately female), level of support, and race (predominately White). Table 1 provides a comparison of these homes. The homes ranged in capacity from 50 to 109 residents. All homes were below their licensed size and had, on average, 16 empty beds. In general, residents required assistance with a number of activities of daily living (ADLs) including needing help with transferring, taking medication, dressing, bathing, and toileting. Aster Gardens chose not to share demographic information on their residents. However, our observations found the population to be most similar to Somerset Manor and Forest Glen.

Table 1.

Select Characteristics by Facility

| Characteristic | Rosewood Hills | Somerset Manor | Forest Glen | Aster Gardens | White Sand Plantation | Sycamore Estates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | 50 | 60 | 109 | 75 | 75 | 70 |

| # of residents during study period | 43 | 48 | 90 | 65c | 40 | 58 |

| Ownership | Corporate | Corporate | Corporate | Corporate | Private | Private onthly |

| fee range | $3050 – $3200 | $2993 – $3850 | $1995 – $4075 | $2195 – $5545 | $3000 – $3700 | $1200 – $4000 |

| Religious culture | Baptist | Various Resident’s Choice | Various Resident’s Choice | Various Resident’s Choice | Various Resident’s Choice | Various Resident’s Choice |

| Religious activities | Daily Devotionals Residents pray for one another | Weekly Church Service | Daily Spiritual and Emotional Activity | Weekly Church Service | Weekly Devotionals | Weekly Devotionals |

| Percent men | 21 | 19 | 37 | Not Reported | 28 | 36 |

| Percent racial minority | -- | 6 | 3 | Not Reported | 2 | 10 |

| Percent under 65 | -- | 6 | 6 | Not Reported | -- | -- |

| Percent over 85 | 67 | 48 | 6 | Not Reported | 77 | 57 |

| Percent non-widoweda | 7 | 6 | Not Reported | Not Reported | 30 | 10 |

| Percent requiring assistance with two ADLs | 43 | 13 | 10 | Not Reported | 50 | 22 |

| Percent requiring assistance with three ADLs | 43 | 23 | 20 | Not Reported | 50 | 78 |

| Percent with dementia diagnosis | 37 | 21 | 39 | Not Reported | 75 | 49 |

| Dementia care unit | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yesb | Yes |

| Percent unable to exit without assistance | 67 | 21 | 10 | Not Reported | 60 | 0 |

Figures include divorced, currently married, and never married

Totals reflect residents in dementia care unit for this facility, but not other facilities

Figure is estimated

Following the selection and consent of each AL, the study PI and trained doctoral students began building rapport with residents, staff members, and family members by attending activities, residents’ council and staff meetings, and placing introductions in newsletters. Our team spent approximately 200 hours across the six homes volunteering and observing day-to-day activities of residents. Interviews with residents were solicited through personal contact with residents and flyers distributed in the home. We aimed to achieve variation in our sample to include men and women who were single (never married), divorced, widowed, and married. We did not recruit residents living in dementia care units or who had known cognitive impairment. All participants were offered a $25 incentive to participate. Additional details of the recruitment and selection process are detailed in previous work by the authors (Burgess, Barmon, Moorhead, Perkins & Bender, 2016; Barmon et al., 2017).

The team conducted open-ended, semi-structured individual interviews with 24 residents. One interview was excluded from the final sample (n=23) due to cognitive impairment which resulted in a limited ability to respond to the interview questions. Participant characteristics are further detailed in Table 2. Individual interviews lasted between 14 and 88 minutes and the average length of interviews was 28.4 minutes. Interviews were conducted in private resident rooms or private spaces within the facility. Interviews began with a discussion of reasons for selecting the facility and general satisfaction with activities, care, environment, and privacy. The majority of the interview focused on perceptions of dating, intimacy, and sexual behaviors within the facility including probes about opportunities for sex and intimacy, desire to engage in intimate or sexual behaviors, and same sex relationships. Additional questions were asked about appropriate behaviors and how and when staff or family should intervene. See Table 3 for a sample of the interview guide.

Table 2.

Resident Characteristics

| Characteristic | n |

|---|---|

| Age Group | |

| 55–64 | 2 |

| 65–74 | 4 |

| 75–84 | 11 |

| 85–94 | 6 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 16 |

| Male | 7 |

| Race | |

| Black | 1 |

| White | 22 |

| Marital Status | |

| Divorced | 9 |

| Married | 7 |

| Single | 1 |

| Widowed | 9 |

| Education | |

| GED | 5 |

| HS Diploma | 7 |

| Trade/Vocational Training | 8 |

| Some college or Associates Degree | 1 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 2 |

| Subjective Health | |

| Fair | 4 |

| Good | 14 |

| Excellent | 5 |

| Length of residence | |

| <1 year | 8 |

| 1–2 years | 10 |

| 3–4 years | 3 |

| 5+ years | 2 |

| Distance from previous residence | |

| <25 miles | 15 |

| 25–75 miles | 5 |

| >75 miles | 3 |

Table 3.

Sample Resident Interview Questions

| Main Question | Topics for Probes (not exhaustive) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tell me a little about the decision to move here. | Involvement in decision; precipitating causes; additional factors in decision |

| 2. | Describe you average day. | Activity involvement; interest in activities |

| 3. | What is it like to live here? | Satisfaction; staff interactions; resident cohesion; desire for change |

| 4. | How much privacy do you have? | Satisfaction; privacy violations; rooms v. common areas |

| 5. | What are your thoughts on dating and intimacy in assisted living? | Same-sex relationships; appropriateness; privacy |

| 6. | Have you noticed people form romantic relationships here? | Sexual or dating behaviors; frequency; consequences |

| 7. | What do you think are appropriate/inappropriate sexual or intimate behaviors in assisted living? | Perception of agreement from other residents; what should happen when perceived inappropriate behaviors occur |

| 8. | What kinds of freedoms of sexual expression do you think residents should have? | Residents with dementia; differences in cognitive function between two residents |

| 9. | Are there residents, including yourself, who would like to be involved in romantic or intimate relationship but don’t have the opportunity? | Barriers; consequences; perceived social or demographic differences; other resident reactions |

| 10. | How have your ideas about of sexuality and intimacy changed as you’ve gotten older? | Changes at various life transitions (marriage, divorce, death of spouse) |

| 11. | How have you attitudes and approaches to issues of sexuality and intimacy changed since you moved here? | Reasons for changes |

| 12. | Is there anything we haven’t covered that you think is important to discuss or to know about regarding residents’ sexual and intimate behaviors? |

Data Analysis

All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed in their entirety. Data were analyzed using a combination of across-case and within-case analysis (Ayres, Kavanaugh, & Knafl, 2003). The team initially analyzed the data using the tenants of grounded theory methods (GTM) (Charmaz, 2006; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). GTM uses constant comparative methods, allowing us to identify key themes and concepts that emerged from the data. In the early phases of data collection and analysis, we created initial codes through careful reading of several transcripts and independent line-by-line coding. The analysts met on a weekly basis to further refine coding and create a final coding structure, which was applied to subsequent transcripts and field notes. As we refined our categories, we used theoretical sampling to link these with relevant concepts in the literature (Morse & Field, 1995). For example, a process we identified as “strategies” was refined using the concept of accounts (Bonneson & Burgess, 2004; Scott & Lyman, 1968) from the symbolic interactionist tradition. Later interview guides were modified to achieve theoretical saturation of concepts as the collection and analysis process progressed. A more thorough description of our GTM coding process is detailed in previous work by the authors (Burgess et al., 2016; Barmon et al., 2017). Tentative relationships or connections between the themes were explored, modified, and confirmed to inductively produce a model of sexual desire in ALs.

Using GTM coding techniques allowed us to identify the important themes and categories for understanding sexuality in AL; however, in many cases resident desire was more implicit than explicit. In order to ensure we were fully capturing resident experiences, the first author engaged in “overreading” of interview text (Ayres et al., 2003; Poirier & Ayres, 1997). Overreading allows the analyst to examine repetitions, omissions, or incongruences in individual accounts that might be difficult to identify when using across-case coding techniques. While reading participant narratives, the first author compared text within each individual interview to itself and to all other interviews in the sample using the themes generated from the grounded theory analysis as a framework. These combined analyses led to our identification of a process of negotiating a lack of intimacy in AL. The term intimacy in this paper emerged from the language and experiences of our participants. Intimacy includes a broad continuum from flirting and teasing, romantic touch, romantic companionship, and partnered sexual behaviors. After the model was complete, all authors reviewed the model to confirm it accurately depicted the complex interaction between the individual and personal desires for intimacy (desires), the social and cultural contexts of AL (barriers), and individual explanations about acting on desire (strategies). We used NVivo 11 (QSR International, 2016) to assist with data management and storage of all qualitative data and SPSS 16 for descriptive statistical information.

Findings

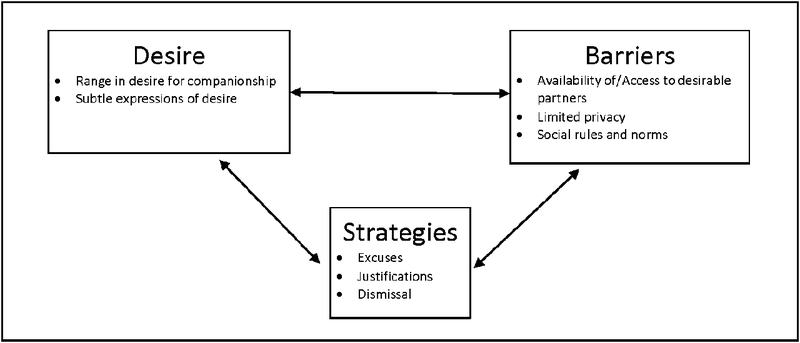

The process of negotiating the lack of intimacy in AL entailed three factors: desire, barriers, and strategies. As shown in Figure 1, residents’ explanation of the lack of intimacy in AL reflected their experiences of desire, barriers, and strategies. Furthermore, these expressions and experiences are embedded in the social and interactional context of AL. Desire was implicitly and explicitly present in resident responses to the question, “what do (or might) residents want for companionship?” The expression of desire ranged from no desire to actively trying to find an intimate companion. This was present in subtle ways, such as flirting and joking, as well as overt ways as trying to sit with someone or walk them to their room. The category of barriers explained the limits to seeking intimacy and included subtle and obvious institutional and individual level barriers. Strategies included residents’ excuses and justifications for not wanting intimacy as well as active dismissal of desire when desire was not met with opportunity for partnership. These three categories were dynamically related to one another and had varying levels of influence in an individual’s narrative. For example, a resident might express desire through flirting (desire), but experience social sanctions for violating social norms (barrier), which results in an active dismissal of desire (strategy). Alternatively, a resident might express no desire for intimacy (desire), but provide an excuse, such as “I’m too old” for their lack of desire (strategy). The model allows for variability in life course experiences before and during AL residency that influences one’s narratives and experiences. Expressions of desire and engagement of strategies could shift across time or place depending on the number and types of barriers and opportunities present.

Figure 1:

Negotiating the lack of intimacy in assisted living

Desire

Range in desire.

The sense of longing for intimacy was expressed in various ways by residents in AL and ranged along a continuum from no interest to actively seeking an intimate relationship. When asked directly about desire, few residents immediately responded that they wanted an intimate relationship, but further probing revealed an underlying desire. Female resident’s spoke of wanting a man who will “put his arms around you and pull you up a little bit,” pamper you, or sit with you. Residents also wanted human touch or attention:

I think [people want relationships], I really do…everybody needs a human touch. You know whether it’s friendly, sexual, or just somebody walking by and patting you on the arm, or patting you on the back. We all crave you know that kind of touching or attention. You know we don’t want to be a number. We have room numbers, but I’m a real person behind that door. (Gloria, Somerset Hills)

While women talked about desire in more general terms, men were more willing to talk about their own desire for intimacy. For example, Donald at Forest Glen said:

And you read stories about romances in these facilities so you figure what the hell, why not. It doesn’t work out. I’m always telling these women, “You don’t use it, you’re going to lose it”…The hell with sex—you just want companionship. Sex is the last thing at my age you want. And you just want to have someone to talk to and someone you can count on. It seems impossible….I’m not looking for sex. I’m looking for companionship…Someone to talk to. Cuddle with…I said, “Let’s go to bed and cuddle.” [Laughs]

Subtle expressions of desire.

We found flirting, teasing, and sexual joking were subtle expressions of desire in AL. In some cases, this behavior was merely a way to pass the time or feel wanted and not an overture to sexual behavior. Although residents frequently described seeing others flirt or engaged in flirtation, it was rarely reciprocated. For example, Ethel at Forest Glen said, “I’ve had lots of flirting done with me but…I’m not about to get connected with another man. Even though some of them have tried it.”

Sexual joking was also present in some facilities, but rarely taken seriously. Charmaine, a newer resident at Forest Glen relayed the following exchange:

The females seem to be fighting back from…’I’m not going to die here. I was brought here to die.’ And somebody made a sexual comment and I found it amusing…She says, ‘Well, death may not be so bad after I have my chance again with a man.’

Sexual joking among residents was evidence that some level of desire for intimacy existed, but was rarely acted upon.

Barriers

The context of AL presents a unique set of barriers for intimacy. Most of the residents in this study thought fellow residents could be in a relationship if they wanted while simultaneously listing barriers to finding intimate companionship. These included the availability of and access to desirable partners, limited privacy, and social rules and norms, including gossip and the perception that dating and intimacy are forbidden in AL.

Availability of and access to desirable partners.

The availability and access to desirable partners was limited by both the structure of the AL environment and the demographics of the AL population. Most facilities were closed environments where the ability to establish new intimate relationships outside the AL were curtailed. For example, the front door at White Sands Plantation was kept locked and all residents, regardless of cognitive status, needed permission to leave. Although other facilities were unlocked, they were located in areas without walkable amenities. Somerset Manor, Aster Gardens, and Sycamore Estates were located on busy commercial throughways without sidewalks or crosswalks nearby. As a result, residents rarely left the facility except by car in the company of others such as an AL sponsored trip or family member. Donald, a resident at Forest Glen who was very interested in finding an intimate partner said, “Well, I couldn’t date because you’re locked in this place, unless you have a car. Where are you going to date, you know?” Mick, a resident at Sycamore Estates, compared his current living situation to his previous independent living situation:

When I used to sit at my other place there was a gal who was a hooker who stayed there…did we have intimacyyyy, yes. Did I have intimacy with anybody else there, yes. But that was there, and this is now and that’s a different story.

Thus, the characteristics of the residents shaped the opportunity structure for intimacy within AL. In homes with fewer men, particularly those perceived as potential partners, there was limited opportunity for cross-sex relationships to develop because, as Gloria from Somerset Hills noted, “the pickings are very slim.” Emily at White Sands Plantation said: “We have…only three men. And grumpy old men. And so I don’t think there’s any relationships… nobody would want those three.” The health status of the residents also made a difference. If the vast majority of the residents in a home were frail and experiencing cognitive decline, then interest in and opportunities for intimacy were further limited. Additionally, none of the residents in this study disclosed a desire for same-sex intimate relationships.

In some of the larger ALs there were more men, but they tended to self-segregate. At Forest Glen, Rose reported:

The men here, I must say, they stay pretty well together. They’re not minglers with the women to speak of. They stay pretty well as a group of men. Like they eat together, they play cards together and very rarely do you find one of them that will sit down and talk with a woman—it’s very unusual. They’ll say, ‘Good morning,’ and ‘How are you?’ But sitting down, having a conversation—I’ve never had one come up to me…They stay pretty well to themselves.

Limited privacy.

Lack of privacy was also a seen as a potential barrier to intimacy for residents. The design of AL, with residents predominately living in private rooms, should provide opportunities for privacy; however, actions of staff limited the privacy residents experienced. Gloria, a resident at Somerset Manor, explained the need for staff to be more respectful of residents’ privacy:

One of the main [barriers] I would think of would be privacy. And we don’t have it here…talk to anybody in here. They get dressed and undressed in the bathroom because it’s the only time they can have privacy is to close that door and flip the lock on it. Most of ‘em [staff] it’s one quick knock and the door’s open. Some don’t even do that…that’s wrong…You know there’s a lock on the door but that doesn’t stop ‘em. They have keys. Which they should. But you know to have intimacy? That’d be real tough unless you plan, you know hanging out in the bathroom, I don’t know how a person would even manage it. Because, as I said, one quick knock and some of ‘em don’t do that.

Social rules and norms.

We found that subtle and overt social norms influenced the actions of and interactions between residents, creating additional in barriers to intimacy for residents in AL. For example, residents feared being the subject of gossip. Emily at White Sands Plantation explained:

I think it would be difficult for a woman and a man in the same place to meet and start dating here. Because boy-oh-boy everybody would be yapping from the minute that happened, and I would think it would be not a good situation.

Rose (Forest Glen) elaborated, “I think [going] in the room, that would not be good. They would be looked down upon at no end. By the majority they would be looked down upon, believe me.”

Mildred was one of the few women at Rosewood Hills that was interested in a relationship but had a difficult time finding anyone interested. She provided an example of how gossip and criticism occurred when she tried:

When I first moved over here and Howard, big Howard come in, I flirted with him. And sit at the table with him. All the time. When he eats, we eat together. But they criticize, the criticisms just got a little strong. So I just up and got me another table.

Regardless of whether residents acknowledged a desire for intimacy, the expression of interest was tempered by social norms about the appropriateness of intimacy in AL and the perception of the culture within the facility. These perceptions ranged from believing some dating might be appropriate to describing all intimate behaviors as inappropriate or “a sin.” Some residents believed any intimate behavior, especially those involving sexual contact, is forbidden and banned within AL despite the absence of policies or discussions regarding restrictions of such behavior. For example, Genie perceived concrete barriers to dating, “I don’t think they’d let you date here. Uh uh. Well I know they wouldn’t let you go out unless you had somebody—a chaperone.” In contrast, others mentioned subtle ways that intimacy was limited. Howard from Rosewood Hills explained, “Thing is [the administrator] runs a tight place. And I don’t think it could go on if it really was out here…So I think this, I would think as far as cleanliness of mind here is great.”

In one instance, a resident described the social sanctions from the administrator and his family when he tried to pursue an intimate relationship with fellow residents. He explained:

I would, you know, talk to the women that are young yet—young. Well I mean that--that can understand my language. And they called my daughter and says, “You better watch your father. He’s getting too aggressive with these women.” [Laughs] I’d walk them home after a movie over here. Or you know I’d talk with them, I’d sit with them. So I says, well, I’m not going to change my personality for anybody and let it go at that. (Donald, Forest Glen).

Strategies

We found three main strategies residents used to negotiate the lack of intimacy in AL: excuses, justifications, and dismissal. These strategies are born from social interactions with others in AL and serve as ways for residents to maintain their identities and status when faced with the gap between desire and opportunity. Excuses were self-directed and minimized desire while denying any responsibility for doing so. Rather, residents attributed external sources, such as age or health. Justifications also minimized desire, but accept some responsibility for the act. Justifications included responses about dyadic concerns in a relationship such as not wanting to be a burden or to care for another person or continued dedication to a deceased spouse. Although rare, some residents enacted a strategy of actively dismissing their own desire. The strategy of dismissal served as an aligning action between desire and barriers and was apparent in resident narratives with high levels of desire who experienced multiple barriers.

Excuses.

When directly asked if they had desire for dating or sex, most residents immediately responded “no” with a quick explanation why they were not interested. Many residents excused their lack of desire by invoking biological reasons, including age and health. The most common reason given was that they were “too old for that.” Female residents explained that as you get older “you get less interested in men,” and the man would “have to be very, very special.” Strategies existed in relation to desire and the barriers previously discussed. For example, Eunice (Aster Gardens) initially said neither she nor her peers would be interested in dating because they were old, but “if there were more men here, yeah, they probably would, but I don’t know (chuckles). That’s a hard thing to say after you get on, up in years.”

Men also relied on the narrative they were too old to date, but frequently couched it in discussions of erectile dysfunction (ED). For example, Tom at Aster Gardens equated sexual function with desire. After explaining he had ED, he said,

When you’re 85 years old, you don’t worry about things like that…nature takes care of that…old age takes care of that. So you no longer have desire. But age takes care of it. But if I had somebody to make love to that I could, I’d load up on Viagra and I’d still take care of that, take care of myself. But there’s no reason to do it if you don’t have anybody to make love to.

Justifications.

Residents also discussed how their age would be a limiting factor for the interpersonal aspects of a relationship, which justified their lack of desire. This included not “having the patience” for another person’s needs or feeling like their health problems would be a burden to others or that it would be unfair. As Howard at Rosewood Hills said,

To dump this old eighty year old body with anybody would the biggest crime that I know of. Stop to think about that. I mean really. I don’t think that it would be to the good of the people even that were participating in it to for themselves. Friendship, I’m all for it.

The environment of AL is dominated by the experience of widowhood. On the individual level, the residents were predominantly women and most were widows. Being a widow or a widower strongly influenced individual’s attitudes and behaviors about intimacy. We found that many widows and widowers in AL maintained a deep connection with their deceased spouse. Residents used their status as a widow or widower to justify their lack of desire in forming future relationships. Violet, a resident at Aster Gardens, shared: “well at times you get very lonely, especially after my husband passed away. Of course I’ve not met anyone of that caliber.” Ethel, a newly widowed resident at Forest Glen, described her reaction when a fellow resident started flirting with her:

When you’re married almost 60 years to the same man it’s hard to go on without him period. But especially somebody that wants to have a real deep relationship. I can’t handle it. Not yet. Maybe later…I’m hoping later. No, I don’t even think about that because I just loved him so much. And so I don’t want to do anything that would look bad or make me feel bad and so I just stay away from other people.

Both widows and widowers maintained physical cues of their ties to former spouses. Many continued to wear wedding rings. These ever present images and reminders also served as barriers for those that were interested in pursuing relationships with widows and widowers.

While most regarded their former or deceased spouse with reverence, some residents described dating or intimacy as a chore or in negative terms. Emily, a divorced woman at White Sand Plantation said she had no interest in dating because she did not “want to start all over again and try and train another one. [Laughing] I did my job on one.” Additionally, because many people move to AL for support, some residents felt it was time to focus on their own needs and not the needs of others. For example, Eunice at Aster Gardens said:

Well, you know when you have a man or somebody…you have to consider them and have to kinda concede to what they want to do at times and I, at 86 years old, I don’t want anybody to look after but myself (chuckles).

Female residents described not trusting others in the AL as justification for not having desire. Building trust takes time and for some it takes longer than others. This lack of trust impacted their ability to consider companionship. Roberta, a resident at Somerset Manor said she avoided getting close to people if she feels they are “getting too friendly” because she just doesn’t “trust people.” Others felt that “in a place like this [AL], you don’t ever know who you can trust.” Ethel, a resident at Forest Glen, described her fears about men’s ability to control their urges. She said, “some men are…he’ll grab you and do something with you if he could.” Ethel used her fear as a justification to limit her contact with two men flirting with her.

Dismissal.

Not all strategies were used to explain a lack of desire. Although less frequent, some residents used strategies to further explain barriers to acting on their desire. For residents who expressed desire and tried acting on it, when the barriers to intimacy became visible they actively tried to dismiss their own desires. For example, Mildred at Rosewood Hills said, “I’d just forgot about it [intimacy]. Just let all that kind of stuff just forget. Just don’t even look at it. And I don’t even think about it.” Mick also described needing to “just leave it [intimacy] alone” since he moved into Sycamore Glen “because there’s nobody here to get involved with.” When faced with the barrier of access to desirable partners, Mick actively dismissed his desire.

Discussion and Conclusion

Some residents expressed a range of desire for intimacy in AL, but there was a marked absence of dating and intimate behaviors. Negotiating the lack of intimacy emerged as central to the experiences of residents in our study sites. The lack of intimacy has implications for resident quality of life within AL. Desire for intimacy, human touch, and attention does not automatically go away when moving into AL or as people age (Karraker & DeLamater, 2013; Lindau et al., 2007). People carry their previous life experiences, including wants and desires, into these settings (Carpenter, 2010). In some cases, they enact strategies (i.e., excuses, justifications, and active dismissal of desire) to remove desire from the equation, especially when facing barriers.

Although all forms of LTC present challenges for intimacy, barriers in AL are distinct because the philosophy embedded in the AL industry does not always align with residents’ experiences within AL (Barmon et al., 2017; Perkins et al., 2012). An additional challenge to negotiating intimacy in AL was the variability in levels of dependency and expressions of desire in each facility. We found numerous barriers to intimacy in the AL environment where the sexual marketplace is even more limiting due to residents’ health and functional status. Our research highlighted additional barriers to desire, lack of privacy, and social norms including the fear of gossip, which were specific to the AL environment. Without access to truly private spaces, many AL residents are not comfortable pursing relationships. This finding supported existing research (Barmon et al., 2017; Villar et al., 2014). In the enclosed environment of AL, peers and staff monitored intimate behavior. In some ALs, flirting and dating were more common, particularly if the sex ratio allowed for opportunity, while in others, sexuality and intimacy were suppressed. Some residents in these homes were quick to rebuke even the innocent or light-hearted flirting from male residents. This parallels research that found widows rejected cross-sex friendships out of concern that men or peers might perceive it as romance (Adams, 1985; van den Hoonaard, 2001). The sex-ratio in the homes in our sample ranged from approximately 1:5 in Rosewood Hills and Somerset Manor to 1:3 in Forest Glen and Sycamore Estates further restricting intimate partnership opportunities. It is possible that lesbian and gay seniors resided in these homes, but chose not to disclose to the research team, fellow residents, or care staff. This could have been out of concerns about discriminatory care or treatment from fellow residents or care staff (Czaja et al., 2016; Furlotte, Gladstone, Cosby, & Fitzgerald, 2016; Stein, Beckerman, & Sherman, 2010).

This research expands previous studies of sexuality and older adults by examining the complex ways in which AL residents balanced desire, barriers, and strategies to negotiate the lack of intimacy in this environment. Regardless of the priority of desire for intimacy in their lives AL residents express desire, face barriers, and enact strategies in relation to others in AL. Drawing on the symbolic interactionist tradition, we found that strategies, much like accounts (Scott & Lyman, 1968), were techniques residents used to manage social interactions related to sexuality and intimacy in AL and served as aligning actions when desire and opportunity were out of balance (Bonnesen & Burgess, 2004; Scott & Lyman, 1968). AL residents also drew on dominate stereotypes of sexuality and aging in order to reinforce the notion that they were “too old” to purse intimate relationships. This internalized ageism shapes the experiences of older adults both within and external to AL (Clark, 2011; Jen, 2017; Yelland & Hosier, 2017).

The reminiscence of past relationships may “serve as an important source of intimacy” for older adults who have no other outlet (Connidis, 2006, p. 139). Building on Lopata’s (1981) concept of sanctification, we assert that an expanded notion of spousal sanctification recognizes a reprioritizing of current or future intimate partnerships in favor of focusing on memories of past relationships when opportunities for future relationships are lacking. Other residents coped with the imbalance between desire and opportunity by attempting to manage or ignore their needs for intimacy.

Our findings have implications for practice within AL facilities, it is important for administrators and staff to recognize some residents continue to desire intimacy and it is important to be attuned to group dynamics to include positive things like flirting, but negative repercussions like gossip and criticism. This can be accomplished through staff training about issues of aging, sexuality, and intimacy. Additionally, as facilities change with the ebb and flow of residents to include characteristics such as more men, presence of cognitive impairment, or residents seeking intimacy, facilities will need to be able to adapt to these situations and make space for these residents.

Finally, when choosing AL facilities, it is likely occurring in a time of crisis and questions about intimacy and desire are not part of the selection criteria, especially if an adult child is selecting the facility for the parent. It is important that residents and their families are attuned to these needs and that they are in congruence with the facility structure. Residents who expressed greater desire, but felt their home was restrictive, repressive, or lacking all opportunity also described less satisfaction with the facility as a whole. While we cannot determine causality, it is notable that desire and lack of opportunity for intimacy is connected with quality of life.

This study had limitations. First, this purposive sample of six AL facilities in and around a large Southern city is not generalizable to all AL or different geographic regions. However, our goal was to develop an explanatory model using GTM for examining the negotiation of sexuality and intimacy in AL settings. Future research can explore desire among a broader geographic sampling of AL that would allow for greater variation in a number of factors including age, health status, and religiosity. Second, this research is cross-sectional. Our research was conducted for six to eight weeks in each home, but a longer time frame or multiple time points for data collection would allow for a better understanding of the fluidity of desire over time and how residents’ sexual behaviors might adapt to this change. Third, despite asking about perceptions and opportunities for LGBT relationships, none of the residents in our sample identified as LGBT. There is an increasing recognition of the distinct needs of LGBT older adults and future research is needed to explore the desires, barriers, and opportunities for intimacy for this population (Fredriksen-Goldsen, Jen, Bryan, & Goldsen, 2016; White & Gendron, 2016).

Despite these limitations, our research provides an explanatory framework for understanding sexuality and intimacy in a unique setting. With greater numbers of older adults moving into the AL setting, administrators, staff, and family members must consider the social and intimate needs of residents. AL administrators can play an important role in fostering individual agency among residents through regular staff training regarding myths and stereotypes about sexuality and gender. These factors can also have meaningful implications for outside stakeholders as well. For example, researchers or health professionals should consider the influence of both individual and institutional pressures when designing interventions or programs for residents in AL settings. As a result, future research should explore the salience of lack of intimacy for future cohorts of AL residents. Finally, as new cohorts of residents with more variable marital life course, particularly higher rates of divorce, and different sexual norms transition to AL, the complex and fluctuating influences on residents’ ability to engage in dating, intimacy, and sexuality will continue to be an important element of the social world of long-term care.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the residents who participated in the study. They thank J. Lloyd Allen, Abhinandran Batra, and Marik Xavier-Brier for their assistance throughout the data collection process and thank Molly Perkins, Candace Kemp, and Jennifer Craft Morgan for their feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health to Elisabeth O. Burgess (R21 1AG030171).

Biographies

Alexis A. Bender, PhD, is an Assistant Professor with the Emory Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics in the Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. Her research interests include disability, trauma, and life course transitions; behavioral health; and relationships over the life course.

Elisabeth O. Burgess, PhD, is a Professor of Gerontology and Sociology and Director of the Gerontology Institute at Georgia State University in Atlanta. Her research interests include sexuality and intimacy over the life course, attitudes about age and older adults, caregiving, and aging families.

Christina Barmon, PhD, MPH, is an Assistant Professor of Gerontology and Sociology at Central Connecticut State University. Her research focuses on the intersection between sex, aging, and health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Alexis A. Bender, Email: alexis.anne.bender@emory.edu, Emory University School of Medicine, Division of General Medicine & Geriatrics, 1841 Clifton Road 5th Floor, Atlanta, Georgia 30329, Office: 404-712-6567 Fax: 404-728-6425.

Elisabeth O. Burgess, Email: eburgess@gsu.edu, Georgia State University, 605 One Park Place, Atlanta, GA 30303, 404-413-5210.

Christina Barmon, Email: cbarmon@ccsu.edu, Central Connecticut State University, Social Sciences Hall - Suite 317, 1615 Stanley Street, New Britain, CT 06050.

References

- Adams RG (1985). People would talk: Normative barriers to cross-sex friendships for elderly women. The Gerontologist, 25(6), 605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizenberg D, Weizman A, & Barak Y (2002). Attitudes toward sexuality among nursing home residents. Sexuality and Disability, 20(3), 185–189 doi:https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1021445832294. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging, American Seniors Housing Association, Assisted Living Foundation of America, National Center for Assisted Living, National Investment Center for the Seniors Housing & Care Industry. (2009). 2009 Overview of Assisted Living. Retrieved from https://www.ahcancal.org/ncal/facts/Documents/09%202009%20Overview%20of%20Assisted%20Living%20FINAL.pdf

- Ayres L, Kavanaugh K, & Knafl K (2003). Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 13(6), 871–883. doi: 10.1177/1049732303255359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Hollingsworth C, King SV, & Combs BL (2005). Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Whittington FJ, Perkins MM, Patterson VL, Hollingsworth C, King SV, & Combs B (2000). Quality of life in assisted living facilities: Viewpoints of residents. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 19(3), 304–325. doi: 10.1177/073346480001900304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barmon C, Burgess EO, Bender AA, & Moorhead JR (2017). Understanding sexual freedom and autonomy in assisted living: Discourse of residents’ rights among staff and administrators. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(3) 457–467. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnesen JL, & Burgess EO (2004). Senior moments: The acceptability of an ageist phrase. Journal of Aging Studies, 18(2), 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Shinohara SK (2013). Dating relationships in older adulthood: A national portrait. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1194–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge S, & Street D (2010). Advantage and choice: Social relationships and staff assistance in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65(3), 358–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess EO (2004). Sexuality in midlife and later life couples In Harvey JH, Wenzel A, & Sprecher S (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 437–454). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess EO, Barmon C, Moorhead JR, Perkins MM, & Bender AA (2016). “That is so common everyday…everywhere you go”: Sexual harrassment of workers in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0733464816630635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LM (2010). Gendered sexuality over the life course: A conceptual framework. Sociological Perspectives, 53(2), 155–177. doi:doi: 10.1525/sop.2010.53.2.155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA (2006). Intimate Relationships: Learning from later life experience In Calasanti T & Slevin KF (Eds.), Age Matters: Realigning Feminist Thinking (pp. 123–154). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja SJ, Sabbag S, Lee CC, Schulz R, Lang S, Vlahovic T, & Thurston C (2016). Concerns about aging and caregiving among middle-aged and older lesbian and gay adults. Aging & mental health, 20(11), 1107–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater J (2012). Sexual Expression in Later Life: A Review and Synthesis. The Journal of Sex Research, 49(2–3), 125–141. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.603168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater J, & Sill M (2005). Sexual desire in later life. Journal of sex research, 42(2), 138–149. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Napoli EA, Breland GL, & Allen RS (2013). Staff knowledge and perceptions of sexuality and dementia of older adults in nursing homes. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(7), 1087–1105. doi: 10.1177/0898264313494802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D, Eckert JK, Rubinstein B, Keimig L, Clark L, Frankowski AC, & Zimmerman S (2008). An ethnographic study of stigma and ageism in residential care or assisted living. The Gerontologist, 48(4), 517–526. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias J, & Ryan A (2011). A review and commentary on the factors that influence expressions of sexuality by older people in care homes. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(11–12), 1668–1676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Fennell ML, Tyler DA, Clark M, & Mor V (2011). Growth of racial and ethnic minorities in US nursing homes driven by demographics and possible disparities in options. Health Affairs, 30(7), 1358–1365. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fileborn B, Thorpe R, Hawkes G, Minichiello V, & Pitts M (2015). Sex and the (older) single girl: Experiences of sex and dating in later life. Journal of Aging Studies, 33, 67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Jen S, Bryan AE, & Goldsen J (2016). Cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias in the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) older adults and their caregivers: Needs and competencies. Advance online publication. Journal of Applied Gerontology, doi: 10.1177/0733464816672047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlotte C, Gladstone JW, Cosby RF, & Fitzgerald KA (2016). “Could We Hold Hands?” Older Lesbian and Gay Couples’ Perceptions of Long-Term Care Homes and Home Care. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 35(4), 432–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg TB, Pomerantz SC, & Kramer-Feeley V (2005). Sexuality in older adults: behaviours and preferences. Age and Ageing, 34(5), 475–480. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott M, & Hinchliff S (2003). How important is sex in later life? The views of older people. Social Science & Medicine, 56(8), 1617–1628. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00180-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R, Caffrey C, Rome V, & Lendon J (2016). Long-Term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States: Data From the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014 3 (38). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd CL (2011). Facing age: Women growing older in anti-aging culture (Vol. 1). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Iecovich E, & Lev-Ran O (2006). Attitudes of functionally independent residents toward residents who were disabled in old age homes: The role of separation versus integration. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 25(3), 252–268. doi: 10.1177/0733464806288565 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jen S (2017). Older women and sexuality: Narratives of gender, age, and living environment. Journal of women & aging, 29(1), 87–97. doi: 10.1080/08952841.2015.1065147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karraker A, & DeLamater J (2013). Past-year sexual inactivity among older married persons and their partners. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(1), 142–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01034.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Hollingsworth C, & Perkins MM (2012). Strangers and friends: Residents’ social careers in assisted living. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(4), 491–502. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer N (2009). Late life love and intimacy. Educational Gerontology, 35(8), 752–764. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, & Waite LJ (2008). Sexual dysfunction among older adults: Prevalence and risk factors from a nationally representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57–85 years of age. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(10), 2300–2311. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00974.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, & Gavrilova N (2010). Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: evidence from two US population based cross sectional surveys of ageing. BMJ, 340: c810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, & Waite LJ (2007). A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(8), 762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodge AC, & Umberson D (2012). All shook up: Sexuality of mid- to later life married couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(3), 428–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00969.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopata HZ (1981). Widowhood and husband sanctification. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43(2), 439–450. [Google Scholar]

- Mahieu L, & Gastmans C (2015). Older residents’ perspectives on aged sexuality in institutionalized elderly care: A systematic literature review. International journal of nursing studies, 52(12), 1891–1905. doi:j.ijnurstu.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makimoto K, Kang HS, Yamakawa M, & Konno R (2015). An integrated literature review on sexuality of elderly nursing home residents with dementia. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 21, 80–90. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AJ, & Stratton DC (2001). Resilient widowers: Older men speak for themselves: New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, & Field PA (1995) Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek B, Kurpas D, Gronowska M, Kotwas A, & Karakiewicz B (2013). Psychosexual needs and sexual behaviors of nursing care home residents. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 57(1), 32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Ceña D, Martínez-Piedrola RM, Pérez-de-Heredia M, Huertas-Hoyas E, Carrasco-Garrido P, & Fernández-de-las-Peñas C (2016). Expressing sexuality in nursing homes. The experience of older women: A qualitative study. Geriatric Nursing, 37(6), 470–477. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park NS (2009). The relationship of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28(4), 461–481. doi: 10.1177/0733464808328606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Kemp CL, & Hollingsworth C (2013). Social relations and resident health in assisted living: An application of the convoy model. The Gerontologist, 53(3), 495–507. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins MM, Ball MM, Whittington FJ, & Hollingsworth C (2012). Relational autonomy in assisted living: A focus on diverse care settings for older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 26(2), 214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier S, & Ayres L (1997). Endings, secrets, and silences: Overreading in narrative inquiry. Research in nursing & health, 20(6), 551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. (2016). NVivio qualitative data analysis software (Version 11). Victoria, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu NK, Kemp CL, Ball MM, Burgess EO, & Perkins MM (2013). Coming together and pulling apart: Exploring the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(4), 317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MB, & Lyman SM (1968). Accounts. American Sociological Review, 33, 46–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, & Corbin J (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Beckerman NL, & Sherman PA (2010). Lesbian and gay elders and long- term care: Identifying the unique psychosocial perspectives and challenges. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 53(5), 421–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street D, & Burge SW (2012). Residential context, social relationships, and subjective well- being in assisted living. Research on Aging, 34(3), 365–394. doi: 10.1177/0164027511423928 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syme ML, Klonoff EA, Macera CA, & Brodine SK (2012). Predicting sexual decline and dissatisfaction among older adults: The role of partnered and individual physical and mental health factors. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 68(3)m 323–332. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbs087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker I (2010). Management of inappropriate sexual behaviors in dementia: A literature review. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(5), 683–692. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz RL (2003). Assisted living: The philosophical challenges of everyday practice. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 22(3), 379–404. doi: 10.1177/0733464803253589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoonaard DK (2001). The widowed self: The older woman’s journey through widowhood. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vares T (2009). Reading the’sexy oldie’: Gender, age (ing) and embodiment. Sexualities, 12(4), 503–524. doi: 10.1177/1363460709105716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villar F, Celdrán M, Fabà J, & Serrat R (2014). Barriers to sexual expression in residential aged care facilities (RACFs): comparison of staff and residents’ views. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(11), 2518–2527. doi: 10.1111/jan.12398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, Laumann EO, Das A, & Schumm LP (2009). Sexuality: Measures of partnerships, practices, attitudes, and problems in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(suppl_1), i56–i66. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz T (2002). Crones, dirty old men, sexy seniors: Representations of the sexuality of older persons. Journal of Aging and Identity, 7(2), 99–112. doi:https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1015487101438. [Google Scholar]

- White JT, & Gendron TL (2016). LGBT elders in nursing homes, long-term care facilities, and residential communities In Handbook of LGBT Elders (pp. 417–437). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yelland E, & Hosier A (2017). Public attitudes toward sexual expression in long-term care: Does context natter? Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(8), 1016–1031. doi: 10.1177/0733464815602113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]