Abstract

Background:

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is prevalent among female patients at fracture clinics; however, previous research suggests health care providers (HCPs) are unprepared to identify victims and provide appropriate support. To address this gap in care, we developed an IPV educational program and conducted a study to measure the impact of this program on HCPs’ IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours.

Methods:

We enrolled 140 participants (orthopedic surgeons, surgical trainees, nonphysician HCPs and research and administrative staff) from 7 fracture clinics in North America who completed the 2-hour educational program. We used a pretest–posttest study design to assess knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours. We administered the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey before, immediately after and 3 months after training and generated scores for each of the 10 subscales. Our primary outcome was change in score for the actual knowledge subscale from before training to 3 months after training. We used linear regression to conduct all analyses.

Results:

We found significant improvement on the actual knowledge subscale 3 months after the training (mean difference [MD] 2.44, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.79 to 3.09). We found statistically significant improvements on 7 additional subscales 3 months after training (perceived preparation [MD 1.96, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.13], perceived knowledge [MD 2.05, 95% CI 1.88 to 2.23], practice issues [MD 6.10, 95% CI 4.98 to 7.23], preparation [MD 1.06, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.22], legal requirements [MD 1.50, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.70], workplace issues [MD 1.11, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.26] and self-efficacy [MD 0.54, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.63]) and on all 10 subscales immediately after training (actual knowledge [MD 3.35, 95% CI 2.77 to 3.94], perceived preparation [MD 2.06, 95% CI 1.88 to 2.23], perceived knowledge [MD 2.14, 95% CI 1.98 to 2.30], practice issues [MD 4.08, 95% CI 3.35 to 4.82], preparation [MD 1.04, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.20], legal requirements [MD 1.66, 95% CI 1.47 to 1.85], workplace issues [MD 1.08, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.20], self-efficacy [MD 0.56, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.63], alcohol/drugs [MD 0.20, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.30] and victim understanding [MD 0.15, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.25]).

Interpretation:

Our educational program led to significant improvements in participants’ readiness to manage IPV. This finding suggests HCPs are better prepared to help patients who experience IPV; however, future research should aim to investigate the impact of this program directly on patients.

Intimate partner violence (IPV), also known as domestic violence, is defined as harm inflicted by one’s past or current partner and may consist of physical, sexual, economic or psychological abuse.1 Previous research has shown that musculoskeletal injuries are the second most common physical manifestation of IPV.2 Additionally, a large prevalence study found that 1 in 6 women who present to fracture clinics have experienced IPV in the past year (i.e., current IPV), and 1 in 50 are presenting for an injury sustained directly from IPV.3 This means that for every 1000 female patients, we can expect that 170 are currently experiencing IPV and 20 are presenting for treatment of injuries directly caused by IPV. Orthopedic surgeons and other health care providers (HCPs) treating women in fracture clinics are therefore well positioned to identify and provide critical assistance to women experiencing IPV. However, they often report feeling unprepared to ask female patients about IPV.4–6 Recent research suggests that these challenges can be overcome with educational programs within a clinical setting.7 However, other research has questioned the effectiveness of educational programs that are implemented without system support at changing actual practice behaviours.8 Despite this, the World Health Organization recommends that HCPs receive IPV training both as part of their schooling and as continuing professional education, emphasizing that training should teach how best to respond to IPV as opposed to solely focusing on how to identify it.9

To address this need in orthopedics we developed EDUCATE, an IPV educational program for HCPs who see patients in the fracture clinic. The purpose of the program was to empower HCPs with the knowledge and skills required to comfortably identify and assist women who have experienced IPV. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of this program on participants’ readiness to manage IPV by determining changes in IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours 3 months after program completion.

Methods

Study design and participants

This pretest–posttest study was designed to evaluate the impact of the EDUCATE program on participants’ IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours. The EDUCATE program was implemented at 6 fracture clinics in Canada (Hamilton Health Sciences–General Site, University of Calgary, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. Michael’s Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre and St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton) and 1 in the United States (The CORE Institute). All 7 fracture clinics provide treatment to patients with a variety of musculoskeletal injuries requiring care from an orthopedic surgeon such as fractures, sprains and dislocations. Participants were orthopedic surgeons, orthopedic surgery residents or fellows, medical students, nonphysician HCPs, clinical research personnel and booking clerks who see patients in the fracture clinic and agreed to complete the EDUCATE program. The number of potential participants across each site varied from 12 to 86 (39 at Hamilton Health Sciences–General Site, 49 at the University of Calgary, 32 at Memorial University of Newfoundland, 28 at St. Michael’s Hospital, 37 at the London Health Sciences Centre, 12 at St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton and 86 at The CORE Institute). All 7 clinics enrolled participants into the study. All participants provided written informed consent.

The EDUCATE program

The EDUCATE program consisted of 3 components: (1) an introductory video, (2) 3 online modules and (3) an in-person training session led by the local IPV champion(s) (Table 1). Following completion of the program, bimonthly training updates were distributed to participants.

Table 1:

EDUCATE program content

| Component | Content | Purpose | Time | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A video presentation about the importance of orthopedic surgeons and other HCPs becoming involved in IPV identification and assistance. The video also introduced the IPV education program. The video is available through https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7NLxpslVro |

|

3 min | Viewed individually at participants’ convenience or as part of the in-person training session, depending on the champion’s preference |

| 2 | Three interactive online modules that are part of the series entitled “Responding to Domestic Violence in Clinical Settings” available through dveducation.ca.22 The modules focus on conveying background knowledge (e.g., definitions, prevalence, dynamics of abusive relationships, barriers to leaving an abusive relationship), as well as clinical skills pertaining to IPV identification and assistance. This training was designed to help trainees achieve competency in identifying and providing assistance to women who have experienced IPV. |

|

Approx. 1 h | Viewed individually at participant’s convenience or as part of the in-person training session, depending on the champion’s preference |

| 3 | The local IPV champion(s) delivered an in-person PowerPoint presentation that included a lecture explaining how to ask women about IPV in the fracture clinic and provide assistance to women experiencing IPV. This presentation included 2 videos demonstrating IPV identification and assistance within a health care setting, as well as 4 case-based scenarios. Champions were provided with mock cases but were encouraged to discuss real-life cases from their practice, if possible. Trainees were given a chance to role play and discuss how they would respond to these cases in their practice. The presentation concluded with a discussion of local IPV policies, protocols and procedures and community resources. Trainees were then provided with an opportunity to ask questions and have a group discussion about the training content. |

|

Approx. 1 h | In-person group training session led by champion |

| Ongoing | Local IPV champions received bimonthly training updates from the Methods Centre (McMaster University). Local IPV champions were responsible for distributing these updates to trainees (e.g., through presentations at rounds, training meetings, and email). |

Note: HCP = health care provider, IPV = intimate partner violence.

The EDUCATE program builds upon a previous educational program developed and evaluated by members of the study team.10 To develop the EDUCATE program, we conducted a scoping review that reviewed and synthesized all of the literature evaluating IPV educational programs in health care settings.7 Additionally, we held in-depth consultations with orthopedic surgeons and a social worker with over 25 years’ experience working with people who have experienced IPV. Finally, drafts of the program were reviewed by members of our knowledge user team, which consisted of representatives from the Canadian Orthopaedic Association, family medicine, emergency medicine, physiotherapy, midwifery and IPV services. The program is based upon Bandura’s self-efficacy theory for changing behaviour.11 As current evidence indicates that a multifaceted approach results in a higher uptake and retention of knowledge, 12 the EDUCATE program includes multiple training methods. The program also incorporates adult learning principles, the hallmark of problem-based learning.13 Problem solving is a central component of self-management and is a key element of most successful individual and group self-management programs reporting improved outcomes.14 Research on both adult education and effective knowledge transfer suggests that interactive strategies are necessary to be successful.15–18

Program delivery

The program was delivered to fracture clinics using a train-the-trainer model. In this model, 1 or more people from each participating fracture clinic (i.e., surgeons, surgical trainees, nonphysician HCPs or clinical research personnel) were identified to become local IPV champions. Local IPV champions received in-depth training about the EDUCATE program from a social worker. The champion training was delivered through a 1.5-hour in-person session held at a large annual meeting of a prominent orthopedic association. The meeting was attended by 7 of the 11 champions from 4 of the 7 participating fracture clinics. The remaining 4 champions from 3 of the participating fracture clinics received training via teleconference. Local IPV champions were responsible for becoming program curriculum experts to implement the program at their local fracture clinics and were encouraged to tailor the training content to maximize applicability.

Study procedures

The EDUCATE program was implemented between Oct. 24, 2016, and June 28, 2017, and study recruitment took place between Oct. 24, 2016, and May 24, 2017. Local investigators and research coordinators invited potentially eligible individuals at their fracture clinic to participate in the study. Data collection occurred at baseline (i.e., before participants completed the EDUCATE program) as well as immediately and 3 months after program completion. All participants completed the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey at baseline and both follow-up periods to assess IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours. The questionnaire was completed either electronically or on paper in the same format at each assessment. Participants were not provided with the correct responses at any point in the study. Additionally, participants completed a demographic questionnaire at baseline. All data collection was performed by local research personnel.

Outcomes

We used the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey to assess changes in IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours.19 The Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey is a self-administered questionnaire and consists of 10 validated subscales that are scored individually: (a) perceived preparation to manage IPV, (b) perceived knowledge of important IPV issues, (c) actual knowledge, (d) preparation, (e) legal requirements, (f) workplace issues, (g) self-efficacy, (h) alcohol/drugs, (i) victim understanding and (j) practice issues.16,19 We determined a priori that our primary outcome would be the change in score on the actual knowledge subscale of the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey from baseline to 3 months after training. This was selected for the primary outcome as it was deemed to be the most clinically important. Additionally, we determined a priori that changes in score for all other subscales of the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey between baseline and 3 months, and changes in score for all subscales of the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey between baseline and the period immediately after training, would be exploratory outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Our sample size was based on the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for the actual knowledge subscale of the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey. As no previous research has been conducted to determine the MCID, we considered one-half of the subscale’s standard deviation (SD) to be a proxy for the MCID. While this is not the standard approach to calculating the MCID, previous research has found that the MCIDs for most health-related quality of life measures can be approximated by half the SD20 and we extrapolated this finding to the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey. Previous research has reported SDs for the actual knowledge subscale of the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey ranging from 5.00 to 5.18.19,21 We used a conservative estimate of 2.5 for the MCID and 8 for the SD of change. Using these assumptions and an α of 0.05 and a β of 0.10, we require a sample size of 110 participants for the analysis to be adequately powered to detect changes. This sample size was inflated to 138 participants to account for an anticipated loss-to-follow-up rate of 20%10 and rounded to a required sample size of 140 participants for convenience.

To analyze the impact of the EDUCATE program on participants’ IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours, we first scored each questionnaire as per the algorithm published by the questionnaire developer.19 Our primary analysis was conducted using multiple linear regression analysis with change in score on the actual knowledge subscale entered into the model as the dependent variable. Additionally, we decided a priori to include pretraining Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey score, age, sex, health care profession and previous IPV training as independent variables in the model to control for potential confounding. We entered pretraining Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey score and age into the model as continuous variables and all other independent variables as dichotomous or categorical variables (i.e., sex, profession and previous IPV training). We entered all variables into the model simultaneously and included all participants who completed the survey at both baseline and 3 months after training. We presented results using a mean difference from baseline to 3 months after training with 95% confidence interval (CI). We repeated this analysis for all exploratory outcomes. Additionally, we conducted an a priori sensitivity analysis to report results obtained from a paired t-test analysis for the primary outcome as well as for all exploratory outcomes. We present mean scores for each subscale for the survey completed at baseline, immediately after training and 3 months after training. All tests were 2-tailed and used an α level of 0.05. We used SAS software, version 9.4, to conduct all statistical analyses.

Ethics approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee at McMaster University and at each participating institution.

Results

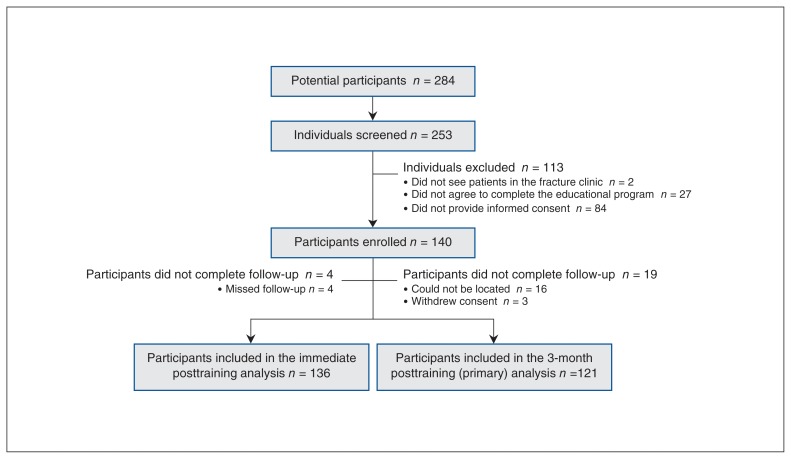

We enrolled 140 participants into the study. Participants included 70 surgical trainees (50.0%), 32 nonphysician HCPs (22.9%), 28 orthopedic surgeons (20.0%) and 10 research or administrative staff (7.1%). We achieved 3-month follow-up for 121 of the 140 enrolled participants (86.4%, Figure 1). The mean age of participants was 35.7 (SD 10.2) years. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1:

Study participant flowchart.

Table 2:

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr,* mean ± SD | 35.7 ± 10.2 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 96/140 (68.6) |

| Female | 44/140 (31.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 107/140 (76.4) |

| South Asian | 16/140 (11.4) |

| East Asian | 11/140 (7.9) |

| Middle Eastern | 3/140 (2.1) |

| Black (African/Caribbean) | 1/140 (0.7) |

| Other | 2/140 (1.4) |

| Profession | |

| Orthopedic surgery resident | 62/140 (44.3) |

| Orthopedic surgeon | 28/140 (20.0) |

| Orthopedic technician | 11/140 (7.9) |

| Nurse | 10/140 (7.1) |

| Research personnel | 9/140 (6.4) |

| Orthopedic surgery fellow | 6/140 (4.3) |

| Physiotherapist | 5/140 (3.6) |

| Physician/surgical assistant | 5/140 (3.6) |

| Medical student | 2/140 (1.4) |

| Occupational therapist | 1/140 (0.7) |

| Booking clerk | 1/140 (0.7) |

| Amount of previous IPV training, h | |

| 0 | 67/139 (48.2) |

| 1–5 | 65/139 (46.8) |

| 6–15 | 7/139 (5.0) |

| Type of previous IPV training | |

| Attended a lecture/talk | 64/72 (88.9) |

| Watched a video | 25/72 (34.7) |

| Completed online training | 9/72 (12.5) |

| Attended skills-based training workshop | 7/72 (9.7) |

| Other | 3/72 (4.2) |

| Setting of previous IPV training | |

| Medical or professional school | 33/72 (23.6) |

| Residency/placement/internship | 20/72 (14.3) |

| Workplace | 18/72 (12.9) |

| Professional education | 12/72 (8.6) |

| Self-learning | 3/72 |

| Volunteer position | 2/72 |

| Research | 1/72 |

Note: IPV = intimate partner violence, SD = standard deviation.

n = 139.

Participants’ scores on the primary outcome, change in score for the actual knowledge subscale of the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey between baseline and 3 months after training, significantly improved (2.44 [95% CI 1.79 to 3.09]). There were no statistically significant differences in the magnitude of improvements experienced by different groups of HCPs (p = 0.24) or between HCPs with previous IPV training and those without (p = 0.59). During this time period, participants’ scores also significantly improved on 7 of the 9 other subscales of the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey (Table 3). No statistically significant differences were seen for the alcohol/drugs and victim understanding subscales between baseline and 3 months after training. Participants’ scores on all 10 subscales of the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey significantly improved between baseline and immediately after training (Table 3). Our sensitivity analyses using paired t tests showed similar results (Table 4).

Table 3:

Change in scores on Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey subscales between baseline and immediately after training and between baseline and 3 months after training

| Subscale* | Score, mean ± SD | Regression analysis, mean difference (95% CI) n = 136 |

Score, mean ± SD | Regression analysis, mean difference (95% CI) n = 121 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Immediately after training | Baseline | 3 months after training | |||

| Actual knowledge | 26.71 ± 4.88 | 30.06 ± 3.95 | 3.35 (2.77 to 3.94) | 26.60 ± 4.79) | 29.04 ± 3.89 | 2.44 (1.79 to 3.09) |

| Perceived preparation | 2.69 ± 1.10 | 4.74 ± 1.14 | 2.06 (1.88 to 2.23) | 2.63 ± 1.06 | 4.59 ± 1.12 | 1.96 (1.79 to 2.13) |

| Perceived knowledge | 2.76 ± 1.10 | 4.89 ± 1.01 | 2.14 (1.98 to 2.30) | 2.71 ± 1.08 | 4.77 ± 1.05 | 2.05 (1.88 to 2.23) |

| Practice issues | 5.53 ± 5.96 | 9.62 ± 5.91 | 4.08 (3.35 to 4.82) | 5.73 ± 6.27 | 11.83 ± 7.74 | 6.10 (4.98 to 7.23) |

| Opinion subscales | ||||||

| Preparation | 3.70 ± 1.17 | 4.75 ± 0.94 | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.20) | 3.68 ± 1.20 | 4.74 ± 0.97 | 1.06 (0.89 to 1.22) |

| Legal requirements | 3.44 ± 1.55 | 5.10 ± 1.17 | 1.66 (1.47 to 1.85) | 3.41 ± 1.51 | 4.91 ± 1.12 | 1.50 (1.30 to 1.70) |

| Workplace issues | 3.04 ± 0.90 | 4.12 ± 0.82 | 1.08 (0.96 to 1.20) | 3.00 ± 0.92 | 4.11 ± 0.88 | 1.11 (0.97 to 1.26) |

| Self-efficacy | 3.56 ± 0.45 | 4.12 ± 0.49 | 0.56 (0.49 to 0.63) | 3.56 ± 0.45 | 4.09 ± 0.57 | 0.54 (0.45 to 0.63) |

| Alcohol/drugs | 4.24 ± 0.55 | 4.44 ± 0.58 | 0.20 (0.10 to 0.30) | 4.26 ± 0.56 | 4.28 ± 0.46 | 003 (−0.05 to 0.11) |

| Victim understanding | 4.94 ± 0.69 | 5.08 ± 0.77 | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.25) | 4.95 ± 0.70 | 4.95 ± 0.78 | 0.002 (−0.11 to 0.11) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation.

Ranges and estimated minimally important clinical differences (MCIDs)† for subscales (range, MCID): actual knowledge (0 to 38, 2.42); perceived preparation to manage IPV (1 to 7, 0.55); perceived knowledge of important IPV issues (1 to 7, 0.55); practice issues (0 to 58, 3.06); preparation (1 to 7, 0.59); legal requirements (1 to 7, 0.77); workplace issues (1 to 7, 0.45); self-efficacy (1 to 7, 0.22); alcohol/drugs (1 to 7, 0.28); and victim understanding (1 to 7, 0.35).

MCIDs were estimated as half the subscales’ standard deviations.20

Table 4:

Change in scores on Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey subscales between baseline and immediately after training and between baseline and 3 months after training

| Subscale | Score, mean ± SD | Paired t-test analysis, mean difference (95% CI) n = 136 |

Score, mean ± SD | Paired t-test analysis, mean difference (95% CI) n = 121 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Immediately after training | Baseline | 3 months after training | |||

| Actual knowledge | 26.71 ± 4.88 | 30.06 ± 3.95 | 3.35 (2.57 to 4.13) | 26.60 ± 4.79) | 29.04 ± 3.89 | 2.44 (1.54 to 3.33) |

| Perceived preparation | 2.69 ± 1.10 | 4.74 ± 1.14 | 2.06 (1.85 to 2.27) | 2.63 ± 1.06 | 4.59 ± 1.12 | 1.96 (1.75 to 2.17) |

| Perceived knowledge | 2.76 ± 1.10 | 4.89 ± 1.01 | 2.14 (1.93 to 2.35) | 2.71 ± 1.08 | 4.77 ± 1.05 | 2.05 (1.84 to 2.27) |

| Practice issues | 5.53 ± 5.96 | 9.62 ± 5.91 | 4.08 (3.29 to 4.88) | 5.73 ± 6.27 | 11.83 ± 7.74 | 6.10 (4.91 to 7.30) |

| Opinion subscales | ||||||

| Preparation | 3.70 ± 1.17 | 4.75 ± 0.94 | 1.04 (0.82 to 1.27) | 3.68 ± 1.20 | 4.74 ± 0.97 | 1.06 (0.81 to 1.30) |

| Legal requirements | 3.44 ± 1.55 | 5.10 ± 1.17 | 1.66 (1.38 to 1.94) | 3.41 ± 1.51 | 4.91 ± 1.12 | 1.50 (1.21 to 1.80) |

| Workplace issues | 3.04 ± 0.90 | 4.12 ± 0.82 | 1.08 (0.94 to 1.23) | 3.00 ± 0.92 | 4.11 ± 0.88 | 1.11 (0.93 to 1.30) |

| Self-efficacy | 3.56 ± 0.45 | 4.12 ± 0.49 | 0.56 (0.48 to 0.64) | 3.56 ± 0.45 | 4.09 ± 0.57 | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.64) |

| Alcohol/drugs | 4.24 ± 0.55 | 4.44 ± 0.58 | 0.20 (0.08 to 0.32) | 4.26 ± 0.56 | 4.28 ± 0.46 | 0.03 (−0.09 to 0.15) |

| Victim understanding | 4.94 ± 0.69 | 5.08 ± 0.77 | 0.15 (0.03 to 0.26) | 4.95 ± 0.70 | 4.95 ± 0.78 | 0.002 (−0.13 to 0.13) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, SD = standard deviation.

Interpretation

Our educational program led to statistically significant improvements in participants’ IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours, both immediately and 3 months after program completion. This suggests that personnel who see patients in the fracture clinic feel better prepared to manage IPV after completing the educational program. Because of the absence of established MCIDs for the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey, it was not possible to determine whether the statistically significant improvements observed in our study were also clinically important. However, previous research has found that the MCIDs for most health-related quality of life measures can be approximated by half the SD.20 Assuming this can be extrapolated from health-related quality of life to the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey, it suggests that changes on 8 of the 10 subscales (actual knowledge, perceived preparation, perceived knowledge, practice issues, preparation, legal requirements, workplace issues, self-efficacy) are also clinically important in testing both immediately and 3 months after program completion. However, this method only suggests the presence of a clinically important improvement so this finding should be interpreted with caution until research establishes the MCIDs for the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey using more precise methods.

Despite the high prevalence of IPV in female patients with orthopedic injuries, only 1 previous study, conducted by members of the study team as preliminary work for the current study, has assessed the effectiveness of an IPV educational program in an orthopedic setting.10 Similar to our findings, this study reported that the educational intervention significantly improved participants’ knowledge immediately following completion of the course (mean difference in scores from baseline to immediately after course: 16% [95% CI 7% to 25%]) and that these improvements were retained 3 months later (mean difference in scores from baseline to 3 months after course: 11% [95% CI 1% to 19%]). However, this study was limited by the small sample size (n = 33), the restriction of the population to surgical trainees from 1 centre and the lack of a validated outcome measurement tool. Our study attempts to build upon this previous work by sampling participants from 7 different fracture clinics, ensuring a sufficient sample size to achieve adequate study power, expanding the population to include any person who sees patients in the fracture clinic and using a validated survey to measure study outcomes.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of our study, it has some important limitations. First, our study used a nonexperimental pretest–posttest design, which produces a lower quality of evidence than randomized controlled trials. However, pretest–posttest study designs are the most common design used to assess IPV educational programs in health care settings.7 These designs are beneficial as they avoid bias that could result from contamination and allow all participants to gain rapid access to training, an issue of particular ethical importance given the high prevalence of IPV. Second, it is possible that our results were influenced by testing bias given that identical tests were administered at baseline and both posttraining assessments.8 However, participants were not provided with the correct responses to the survey at any point during the study and the use of a validated outcome measure is also a strength. Third, our study did not assess program compliance with the introductory video or online module components of the training and consequently we cannot be sure that all participants completed these before the in-person training. However, all participants attended the in-person training session, which is the most essential component of the program. Fourth, we used the approach of Norman and colleagues to approximate the MCID,20 which was developed for use with health-related quality of life measures, and we cannot be certain it is equally valid for use with the Physician Readiness to Manage IPV Survey. However, given the absence of an established MCID, it is the best way available to approximate the MCID. Fifth, while our study achieved an 86% follow-up rate, we were unable to obtain primary outcome data for 14% of participants (n = 19) of participants, which may have introduced response bias. However, our follow-up rate was consistent with, or in most cases better than, follow-up rates reported in the literature.7 Additionally, given the magnitude of the effect sizes, we believe it is unlikely that any bias would change the statistical significance of the results. Finally, our study did not assess the impact of the educational program on patients’ experiences in the fracture clinic. While our study showed that HCPs’ IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours improved after training, it is unknown whether these changes translated into improved patient care. A previous systematic review found evidence that IPV educational programs improve patient care when physicians are provided with training along with system changes or when programs are delivered online using problem-based learning approaches.17 Our program included several of these components (i.e., problem-based learning, interactive online modules, information about local services for people who experience IPV and an IPV resource list for patients). However, this same review also found that brief training for postgraduates that did not include these components resulted in improvements in knowledge but did not translate into behavioural changes. Future research should investigate the impact of the EDUCATE program directly on fracture clinic patients.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that an IPV educational program developed specifically for delivery in a fracture clinic setting improves IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and self-reported behaviours in orthopedic surgeons, surgical trainees, nonphysician HCPs and research and administrative staff. To implement this program, we have partnered with the Canadian Orthopaedic Association (which represents approximately 80% of the orthopedic surgeons in Canada) to make the EDUCATE program available to fracture clinics across Canada. The program can be accessed through www.IPVeducate.com.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: Anthony Adili, Gina Agarwal, Mohit Bhandari, Deborah Cook, Vanina Dal Bello-Haas, Diane Heels-Ansdell, Samir Faidi, Norma MacIntyre, Paula McKay, Brad Petrisor, Angela Reitsma, Patricia Schneider, Taryn Scott, Patricia Solomon, Sheila Sprague, Lehana Thabane and Andrew Worster report receiving grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Hamilton Academic Health Sciences Organization during the conduct of the study. Erin Baker, Richard Buckley, Kayla Cyr, Andrew Furey, Leah Kennedy, Jeremy Hall, Tanja Harrison, Melanie MacNevin, Aaron Nauth, Emil Schemistsch, Prism Schneider, Debra Sietsma and Milena Vicente report receiving a grant from the Hamilton Academic Health Sciences Organization during the conduct of the study. Mohit Bhandari reports receiving personal fees from Sanofi, Pendopharm, Ferring, DJO and Stryker, outside the submitted work. Vanina Dal Bello-Hass reports receiving a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, outside the submitted work. Aaron Nauth reports receiving personal fees and a grant from Stryker, Smith & Nephew as well as grants from DePuy Synthes, the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Osteosynthesis and Trauma Care and Physicians’ Services Incorporated, outside the submitted work. Brad Petrisor reports receiving a grant from Stryker, outside the submitted work. Gerard Slobogean reports receiving personal fees from Zimmer Biomet and Smith & Nephew and grants from the Department of Defense and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, outside the submitted work. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Sheila Sprague and Mohit Bhandari conceived the study. Sheila Sprague, Taryn Scott, Diana Tikasz, Paula McKay, Lehana Thabane, Diane Heels-Ansdell, Patricia Solomon, Deborah J. Cook, Gerard P. Slobogean, Patricia Schneider, Mohit Bhandari, Douglas Thomson, Trinity Wittman, Gina Agarwal, Vanina Dal Bello-Haas, Samir Faidi, Norma MacIntyre, Angela Reitsma, Aparna Swaminathan, Andrew Worster, Ari Collerman, Norma MacIntyre, Sarah Resendes Gilbert and Nneka MacGregor contributed to the study design. Prism S. Schneider, Richard E. Buckley, Leah Kennedy, Tanja Harrison, Brad A. Petrisor, Taryn Scott, Andrew Furey, Kayla Cyr, Erin Baker, Jeremy A. Hall, Aaron Nauth, Milena Vicente, Debra L. Sietsema, Emil H. Schemitsch, Melanie MacNevin and Anthony Adili acquired the data. Diane Heels-Ansdell, Lehana Thabane, Sheila Sprague and Taryn Scott analyzed the data. Sheila Sprague, Taryn Scott, Diane Heels-Ansdell, Lehana Thabane and Mohit Bhandari interpreted the data. Sheila Sprague, Taryn Scott and Diane Heels-Ansdell drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

Disclaimer: The analyses, conclusions and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of affiliated institutions or funding agencies.

Funding: The study was funded by research grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (KAL-147545) and the Hamilton Academic Health Sciences Organization. Mohit Bhandari was also funded, in part, by a Canada Research Chair in musculoskeletal trauma at McMaster University (Hamilton, Ont.), which is unrelated to the present study. The funders of the study had no role in its design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or the writing of the article. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/6/4/E628/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [accessed 2018 Jan 25]. Available: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/Chapter7-Chapter8-Chapter9.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhandari M, Dosanjh S, Tornetta P, III, et al. Musculoskeletal manifestations of physical abuse after intimate partner violence. J Trauma. 2006;61:1473–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196419.36019.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sprague S, Bhandari M, Della Rocca GJ, et al. Prevalence of abuse and intimate partner violence surgical evaluation (PRAISE) in orthopaedic fracture clinics: a multinational prevalence study. Lancet. 2013;382:866–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhandari M, Sprague S, Tornetta P, III, et al. (Mis)perceptions about intimate partner violence in women presenting for orthopaedic care: a survey of Canadian orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1590–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shearer HM, Bhandari M. Ontario chiropractors’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about intimate partner violence among their patients: a cross-sectional survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31:424–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shearer HM, Forte ML, Dosanjh S, et al. Chiropractors’ perceptions about intimate partner violence: a cross-sectional survey. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:386–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprague S, Swaminathan A, Slobogean GP, et al. A scoping review of intimate partner violence educational programs for health care professionals. Women Health. 2017 Dec;18:1–15. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2017.1388334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Reflections on experimental research in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15:455–64. doi: 10.1007/s10459-008-9117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women WHO clinical and policy guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [accessed 2018 Feb 11]. Available http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85240/1/9789241548595_eng.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madden K, Sprague S, Petrisor BA, et al. Orthopaedic trainees retain knowledge after a partner abuse course: an education study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:2415–22. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4325-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gadomski AM, Wolff D, Tripp M, et al. Changes in health care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors regarding domestic violence, following a multifaceted intervention. Acad Med. 2001;76:1045–52. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200110000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood DF. Problem based learning. BMJ. 2008;336:971. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39546.716053.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funnell MM. Peer-based behavioural strategies to improve chronic disease self-management and clinical outcomes: evidence, logistics, evaluation considerations and needs for future research. Fam Pract. 2010;27(Suppl 1):i17–22. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris JM, Jr, Kutob RM, Surprenant ZJ, et al. Can Internet-based education improve physician confidence in dealing with domestic violence? Fam Med. 2002;34:287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Short LM, Surprenant ZJ, Harris JM., Jr A community-based trial of an online intimate partner violence CME program. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:181–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaher E, Keogh K, Ratnapalan S. Effect of domestic violence training: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:618–24. e340–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside JM, et al. How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q. 2003;81:221–48. 171–2. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Short LM, Alpert E, Harris JM, Jr, et al. A tool for measuring physician readiness to manage intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–92. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAndrew M, Pierre GC, Kojanis LC. Effectiveness of an online tutorial on intimate partner violence for dental students: a pilot study. J Dent Educ. 2014;78:1176–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mason R, Schwartz B. Responding to domestic violence in clinical settings. Toronto: Women’s College Hospital; 2018. [accessed 2018 Nov 19]. Available: http://dveducation.ca/domesticviolence. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.