Abstract

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) delivers its protease domain across the vesicle membrane to enter the neuronal cytosol upon vesicle acidification. This process is mediated by its translocation domain (HN), but the molecular mechanism underlying membrane insertion of HN remains poorly understood. Here, we report two crystal structures of BoNT/A1 HN that reveal a novel molecular switch (termed BoNT-switch) in HN, where buried α-helices transform into surface-exposed hydrophobic β-hairpins triggered by acidic pH. Locking the BoNT-switch by disulfide trapping inhibited the association of HN with anionic liposomes, blocked channel formation by HN, and reduced the neurotoxicity of BoNT/A1 by up to ~180-fold. Single particle counting studies showed that an acidic environment tends to promote BoNT/A1 self-association on liposomes, which is partly regulated by the BoNT-switch. These findings suggest that the BoNT-switch flips out upon exposure to the acidic endosomal pH, which enables membrane insertion of HN that subsequently leads to LC delivery.

The translocation domain (HN) of Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs) mediates the delivery of the BoNT light chain (LC) into neuronal cytosol. Here the authors provide insights into HN membrane insertion by determining the crystal structure of BoNT/A1 HN at acidic pH, which reveals a molecular switch in HN, where buried α-helices are transformed into surface-exposed hydrophobic β-hairpins.

Introduction

Many bacterial toxins and viruses gain access to intracellular targets in their hosts by exploiting the endocytic pathway, such as anthrax toxin1, diphtheria toxin2, Ebola virus3, and vesicular stomatitis virus4. Some of the toxins and viruses detect acidification of the vesicle lumen and subsequently change from a water-soluble form to a membrane-embedded form to exert their functions. Botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), the most poisonous biological toxins for mammals, are speculated to exploit a similar mechanism to block neurotransmitter release at neuromuscular junctions that results in fatal botulism5. As some BoNTs, in particular type A1 (BoNT/A1), are powerful medicines as well as potential bio-weapons6,7, a better understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying BoNT/A1 membrane translocation has great potential for improving its therapeutic efficacy and developing antitoxins.

There are seven established BoNT serotypes, designated as BoNT/A to G, which include more than 40 subtypes8. BoNTs are members of single-chain AB toxins that also include diphtheria toxin and tetanus neurotoxin9. A BoNT molecule consists of a light chain (LC) and a heavy chain (HC) that are linked by a disulfide bridge10–12. LC is a zinc-dependent endopeptidase that is delivered into the cytosol where it degrades SNARE proteins to inhibit synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Membrane translocation of LC is mediated by HC, which can be subdivided into a translocation domain (HN) and a receptor-binding domain (HC) (Fig. 1a). The N-terminus of HN forms an extended “belt” that wraps around the LC and links HN to LC via a disulfide bond13. The BoNT HC binds a specific protein receptor and a ganglioside on the neuronal surface to enable toxin endocytosis14–19.

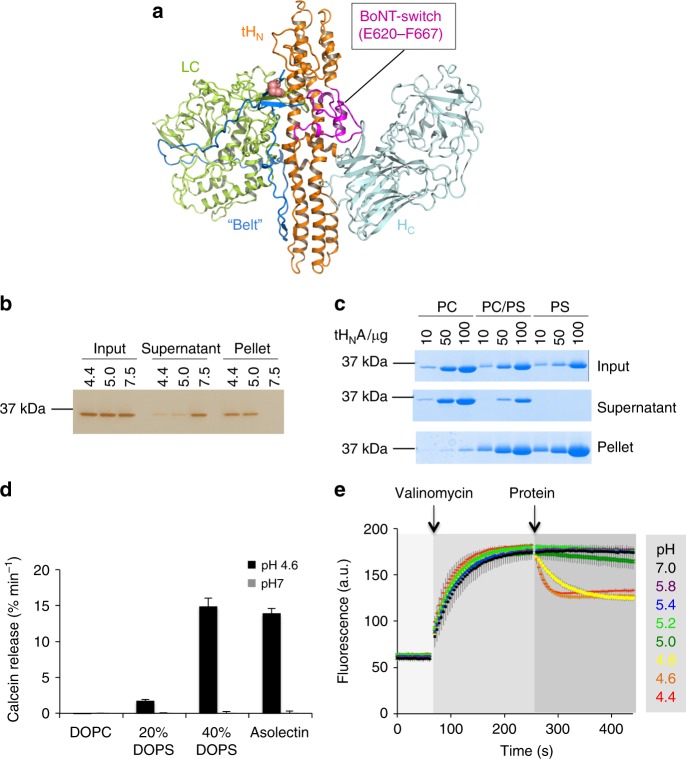

Fig. 1.

Biochemical characterization of tHNA. a The structure of BoNT/A1 (PDB code 3BTA). LC, the “belt”, tHN, and HC are colored green, marine, orange, and cyan, respectively. The disulfide linkage between LC and HN is shown as salmon sphere and the BoNT-switch is highlighted in magenta. b, c Co-sedimentation of tHNA with liposomes. tHNA was incubated with asolectin liposomes at pH 7.5, 5.0 or 4.4 (b); or incubated with liposomes containing 60/40 mol% PC/cholesterol, 30/30/40 mol% PC/PS/cholesterol, or 60/40 mol% PS/cholesterol at pH 4.4 (c). After liposomes were pelleted, the proteins in input, supernatant, and pellet fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. These experiments were performed in triplicate and quantification of protein band intensities are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. Uncropped images of gels are shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. d Calcein dye release assay. tHNA was tested with four different liposomes loaded with 50 mM calcein at pH 4.6 or pH 7.0, whereas liposomes were composed of DOPC alone, 80/20 mol% DOPC/DOPS, 60/40 mol% DOPC/DOPS, or asolectin. The rate of calcein dye release was determined based on the increase of fluorescence at 525 nm during excitation at 493 nm. Error bars indicate SD of triplicate measurements. e Membrane depolarization assay. Liposomes composed of 70/20/10 mol% DOPC/DOPS/cholesterol were polarized at a positive internal voltage by adding valinomycin in the presence of a transmembrane KCl gradient. Membrane potential was measured using the voltage-sensitive fluorescence dye ANS. After 3 min, tHNA was added at the indicated buffer pH. The data are presented as mean ± S.D., n = 3

The mechanisms underlying BoNT membrane insertion and LC translocation have been the subject of considerable debates. Earlier studies showed that BoNT/A1 translocated LC in planar lipid bilayer in the presence of a transmembrane pH gradient, an electrochemical potential, and a redox gradient20,21. It was proposed that acidic pH might induce a structural change of BoNT and promote its interaction with phospholipids17, which is similar to other pore forming toxins2,22,23. Although no conformational change was detected in BoNT at acidic pH in the available crystal structures24, it underwent an unknown structural rearrangement after binding to ganglioside-containing membranes25–29. Furthermore, the HN core lacking the “belt” (termed tHN thereafter, Fig. 1a) was shown to form an ion channel independent of pH, and no clear structural change was detected by spectroscopic methods at acidic pH30–32. Other regions of HN have also been proposed to be involved in membrane insertion33,34. However, the structural rearrangement of BoNT during LC delivery, particularly the trigger for membrane insertion of HN, has not been visualized.

To better understand the mechanism of BoNT membrane translocation, we determined the crystal structure of tHN of BoNT/A1 (tHNA, residues K547–K871) at pH 5.1, as well as a point mutation of tHNA (tHNAF658E) at pH 8.5. To our surprise, these two structures revealed a previously unrecognized amphipathic region of HN (residues E620–F667, termed the BoNT-switch) that undergoes a profound pH-dependent structural rearrangement to form surface-exposed β-hairpins. Furthermore, the BoNT-switch shares a high sequence similarity with the internal fusion loop (IFL) of Ebola virus glycoprotein 2. A combination of structural studies, biochemical assays, single-molecule subunit counting, and functional assays confirmed that, upon endosome acidification, the BoNT-switch triggers the transformation of BoNT/A1 into a transmembrane state for LC delivery, which is essential for its extreme toxicity.

Results

Acidic pH triggers membrane insertion of tHNA

The HN of BoNTs has evaded structural studies due to problematic protein folding during recombinant expression31,32. We and others found that HNA primarily formed inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli, which could be refolded when stabilized by detergent. However, we found that the beltless HN (termed tHNA) could be successfully expressed in soluble form and purified to high homogeneity (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Size-exclusion chromatography-coupled small-angle X-ray scattering (SEC-SAXS) showed that tHNA was monomeric at neutral pH and displayed a conformation comparable to that observed in the crystal structure of full-length BoNT/A110 (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). Thus, deletion of the belt region improves protein folding of HN without altering its tertiary structure.

Some earlier studies suggested that low pH and anionic phospholipids may promote the membrane interaction of HN30–32,35. We conducted a liposome co-sedimentation assay to investigate the effect of pH and lipid composition on tHNA–membrane association. We found that tHNA was co-pelleted with asolectin liposomes at pH 4.4 or 5.0, but not at pH 7.5, indicating that acidic pH enhances the association of tHNA with lipid (Fig. 1b). We then examined liposomes containing different ratios of anionic phosphatidylserine (PS) and neutral phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipids and found that tHNA binding to liposomes at pH 4.4 was greatly enhanced by increasing concentrations of PS. This demonstrates that tHNA shows selectivity for anionic lipids (Fig. 1c).

We further characterized the membrane insertion of tHNA using two complementary assays. First, we monitored the ability of tHNA to permeabilize calcein-entrapped liposomes. We found that tHNA increased the rate of calcein release at acidic pH when liposomes contained the anionic phospholipid 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DOPS) or asolectin, but not when liposomes contained only the neutral lipid 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) (Fig. 1d). We then studied the ability of tHNA to dissipate valinomycin-induced membrane potential in liposomes containing 20% DOPS at different pH (Fig. 1e)36,37, and found that tHNA induced membrane depolarization at acidic pH ( < 5.0). It is worth noting that this pH value is close to the estimated luminal surface pH of synaptic vesicles, which could be one unit lower than that inside the lumen (~5.5)38,39. These results consistently demonstrate that tHNA favorably interacts and inserts into membranes containing anionic lipids at acidic pH.

Acidic pH triggers a structural rearrangement of tHNA

To better understand how acidic pH triggers membrane insertion of tHNA, we crystallized tHNA at pH 5.1 and determined the structure at 2.7 Å resolution (Methods) (Table 1). Two molecules of tHNA form a homodimer in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 2a). Each tHNA is composed of two long coiled-coil helices that are wrapped around by several shorter helices at the two ends, and the overall structure of tHNA is similar to that observed in full-length BoNT/A1 crystallized at a neutral pH10. However, we observed a major conformational change in a central helical bundle (residues E620–F667) of HN. This region, which we term the “BoNT-switch”, is composed of disordered loops and three short helices (αA–αC) at neutral pH, but changes into five β strands (β1–β5) at acidic pH (Fig. 2b).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| tHNA | tHNAF658E | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | H 3 2 | P 63 2 2 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 167.66, 167.66, 222.83 | 158.27, 158.27, 123.97 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 |

| Resolution (Å) | 52.01–2.70 (2.83–2.70)a | 42.87–3.02 (3.20–3.02) |

| Rmerge | 0.064 (0.609) | 0.093 (0.616) |

| CC1/2 | 0.999 (0.711) | 0.999 (0.886) |

| I/σ(I) | 12.8 (2.0) | 15 (3.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.3 (99.1) | 99.9 (100) |

| Redundancy | 4.6 (4.1) | 9.1 (9.3) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 52.01–2.70 | 42.87–3.02 |

| No. reflections | 32906 | 18514 |

| Reflections used for Rfree | 1662 | 946 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.209 / 0.223 | 0.182 / 0.237 |

| No. atoms | 5176 | 2647 |

| Protein | 5144 | 2602 |

| Ligand/ion | 5 | 45 |

| Water | 27 | — |

| B-factors | 85.70 | 83.40 |

| Protein | 85.80 | 83.00 |

| Ligand/ion | 117.60 | 107.10 |

| Water | 65.50 | — |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.167 | 1.116 |

One crystal was used for each structure

aStatistics for the highest resolution shell are shown in parentheses

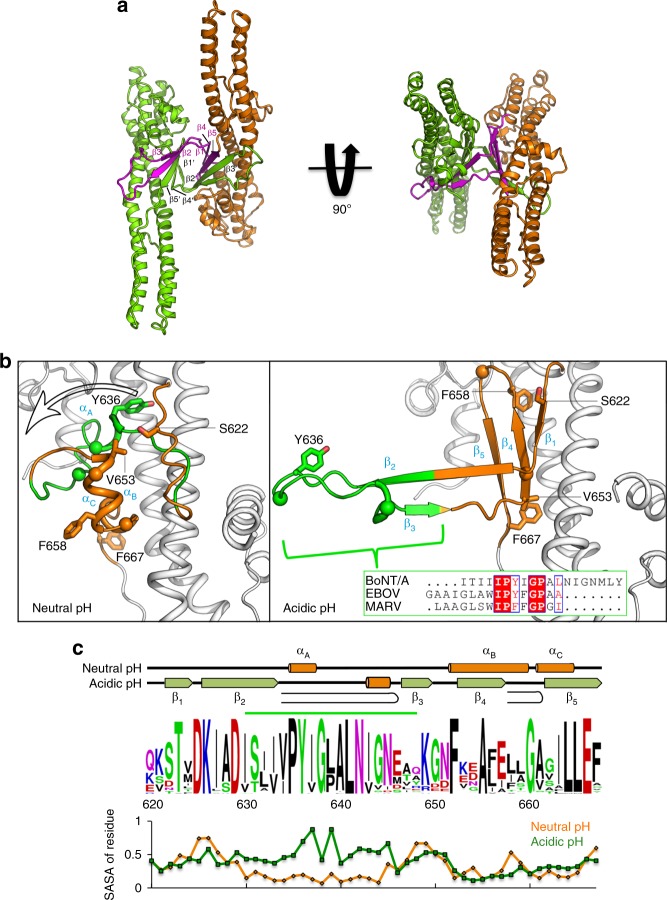

Fig. 2.

Crystal structure of tHNA at an acidic pH. a Structure of a tHNA dimer (orange and green) observed in an asymmetric unit. The BoNT-switch of chain A is colored in magenta. b The structures of the BoNT-switch at neutral (left) and acidic pH (right). The β2/β3 loop is highlighted in green. Residues discussed in the text are shown as sticks, Cα atoms of conserved glycines are drawn in spheres. (Boxed) Sequence alignment of the β2/β3 loop and the internal fusion loops of Ebola virus (EBOV) and Marburg virus (MARV) glycoproteins were generated with ESPript 3.0. c Amino acid sequences of E620-F667 (BoNT/A1 numbering) from 42 BoNT subtypes8, TeNT, BoNT/X, and eBoNT/J were aligned (Clustal Omega) and depicted as sequence logo. Individual sequences are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. The secondary structure of the BoNT/A1-switch at neutral and acidic pH is shown on the top. The β2/β3 loop is underlined in green. The solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) of the corresponding residues is shown at the bottom. SASA was calculated using the program POPS42. The SASA values are for the entire residue and represent fraction of exposed surface area

At neutral pH, αA helix and the surrounding loops (residues I630–Y648, named β2/β3 loop thereafter, labeled green in Fig. 2b) are partially buried in a hydrophobic groove located between αB (residues F652–S659) and the coiled-coil helices (Fig. 2b). The conformation of this region is similar among BoNT/B, D, E, and TeNT. These contacts are stabilized by Y636 that interacts with F585, M732, and I784 (Fig. 2b). At acidic pH, the αA protrudes outward to form the center of the β2/β3 hairpin. This leaves the hydrophobic groove exposed to solvent, thus helices αB and αC transform into the β4/β5 hairpin to partly shield the solvent-exposed surface. The low pH conformation is facilitated by several non-polar residues (V653, F658, and F667). These residues are solvent-exposed at neutral pH, but flip inward at acidic pH. Notably, the highly conserved Y636 that is important for stabilizing the local structure at neutral pH flips out to be solvent exposed at acidic pH. Interestingly, the original position of Y636 is taken over by F658. This finding suggests that F658 may contribute to the pH-dependent conformational transition. Additionally, the BoNT-switch contains several glycine residues (G638, G644, G654, and G660) that likely provide the conformational flexibility to accommodate such a dramatic structural transition (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, the Propka algorithm40 predicted that three acidic residues (E620, D629, and E666) located within the BoNT-switch have increased pKa values in the context of the neutral pH conformation38. Two of these residues, D629 and E666, are locked in hydrogen bonds to S794 and Y250, respectively, while these interactions are released at acidic pH (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, we suspect that these titratable charged residues could be involved in sensing low pH.

As this is the only crystal structure for the isolated tHNA and all the other available structures are for the full-length BoNT/A or LC/A-HNA10,41, it would be informative for structural analysis if we could obtain the structure of tHNA, without the influence of other BoNT/A domains, at a neutral pH. Interestingly, diffraction-quality crystals of tHNA could only be obtained at an acidic pH despite thorough crystallization screens at various pH. We suspected that the isolated tHNA domain may be prone to adopting the acidic pH conformation needed for LC translocation, and its neutral pH conformation could be stabilized by LC/A and/or HCA. Taking advantage of our new crystal structure, we set out to look for point mutations on tHNA that shift the structural equilibrium of tHNA more towards the neutral pH conformation as opposed to the acidic pH conformation. After extensive search and screening, we found that tHNA carrying a single point mutation of F658E could be crystallized at pH 8.5 and we determined its structure at 3.02 Å (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3a). This result is consistent with our structural analysis that suggested F658E may destabilize the acidic pH conformation, but does not directly affect the neutral pH conformation (Fig. 2b). We found that the structure of tHNAF658E is highly similar to the corresponding region in full-length BoNT/A that was crystallized at a neutral pH (root-mean-square deviation of ~0.96 Å). Notably, the BoNT-switch adopts an almost identical structure in tHNAF658E and the full-length toxin (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Taken together, the structures of tHNA at pH 5.1 and tHNAF658E at pH 8.5 allow us to directly visualize how the environmental pH regulates the conformation of the BoNT-switch.

The BoNT-switch is similar to the Ebola GP2 fusion loop

The structural rearrangement of the BoNT-switch causes a ~21% increase in the solvent-accessible hydrophobic surface in tHNA42, which is largely ascribed to the formation of the β2/β3 loop (Fig. 2b, c). The structural and sequence analyses of the BoNT-switch indicate that the solvent-exposed β2/β3 loop is favorable for interacting with lipids, as supported by the hydropathy analysis of the BoNT/A sequence43,44 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Interestingly, these hydrophobic patches in β2/β3, which are energetically not favored in an aqueous environment, are shielded by forming a homodimer in the crystal lattice, which buries a surface area of ~2,625 Å2 per molecule (PDBePISA). Specifically, the tHNA homodimer forms a two-side flattened β-barrel that is stabilized by swapping the β2/β3 hairpin between the two protomers, which forms an antiparallel β sheet with β1, β4, and β5 (Fig. 2a). Dimer formation is stabilized by hydrogen bonds primarily involving the main-chain atoms of β2 and β5 (Supplementary Fig. 5a). As a result, most of the exposed hydrophobic side-chains of the β-hairpins are buried within the tHNA homodimer in the crystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c).

Remarkably, we found that the β2/β3 loop contains a stretch of hydrophobic residues rich in aliphatic side-chains, which shares a high sequence similarity to a lipid-binding peptide of the glycoprotein 2 (GP2) IFL of Ebola virus, a member of the Filoviridae family of enveloped viruses. IFL is known to control viral-host membrane fusion at low endosomal pH by directly engaging the host membrane45 (Fig. 2b). The loops in both BoNT/A1 and GP2 contain an “aromatic-hydrophobic-glycine” tripeptide motif flanked by two proline residues, which would favorably interact with the interfacial region of lipid bilayers46. Amino acid sequence alignments among the 44 known BoNT subtypes, including the recently identified BoNT/HA47, BoNT/X48, and eBoNT/J (aka BoNT/En)49,50, as well as TeNT, showed that the sequence of the β2/β3 loop is highly conserved, suggesting a functional role for this loop in BoNTs (Fig. 2c). We noted that the second proline (P639) is conserved among BoNT/A, C, D, G, X, and TeNT, but this residue is replaced by a leucine in BoNT/B, E, F, and HA or an asparagine in eBoNT/J (Supplementary Fig. 6). Such variation may indicate that the structure of the BoNT-switch when inserted into membrane could be different from that of the viral-fusion-loop of GP2.

The BoNT-switch is important to the membrane insertion of HN

To further characterize the role of the BoNT-switch in membrane insertion of tHNA, we engineered a covalent tethering between loopA and αB by replacing S622 and V653 with cysteines (named tHNADS) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 7). The crystal structures showed that these two solvent-exposed residues are 5.3 Å apart (Cβ–Cβ distance) when BoNT/A1 is at a neutral pH, but they move away from each other (15.5 Å) upon the conformational change induced by acidic pH. Therefore, the disulfide bridge between S622C and V653C will inhibit the helix-to-strand transition of αB when oxidized, and the inhibition will be released when reduced. To monitor exposure of hydrophobic surface in tHNA, we used 8-anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (ANS) as an indicator that displays increased fluorescence intensity when it binds to hydrophobic patches in a protein (Fig. 3a). We found that ANS intensity in the presence of tHNA remained unchanged at pH 5–7, but dramatically increased at pH below 5.0. This is consistent with our structural data showing exposure of hydrophobic surface in tHNA at acidic pH. The transitional pH for tHNA (~4.82) is similar to that reported previously for full-length BoNT/A (~4.55)29. We then asked whether the structural change in tHNADS could be regulated by the engineered disulfide bond. The reduced tHNADS showed an acidic-pH-dependent increase in ANS fluorescence that was similar to the WT tHNA, indicating that the cysteine mutations on S622 and V653 did not affect the BoNT-switch. In contrast, the oxidized tHNADS did not exhibit a pH-dependent change in ANS fluorescence as there was only a subtle intensity increase at acidic pH. Therefore, the engineered disulfide linkage prevented the acid-induced release of the BoNT-switch.

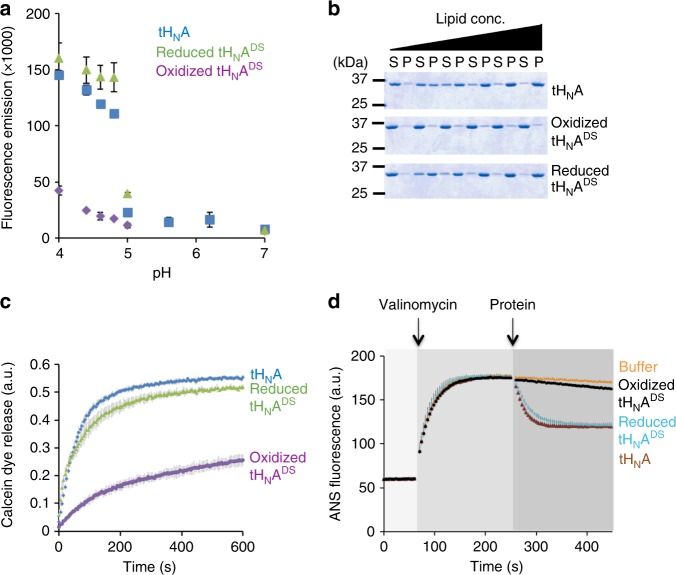

Fig. 3.

Modulating the conformation of the BoNT-switch using an engineered disulfide bond trapping. tHNADS was analyzed by four independent assays: a ANS binding; b liposome association: liposome co-sedimentation was conducted by incubating the WT tHNA or tHNADS with different concentrations of liposomes containing 20% DOPS and 80% OBPC. Supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Quantification of protein band intensities are shown in Supplementary Fig. 12. Uncropped images of gels are shown in Supplementary Fig. 13; c calcein dye release; and d membrane depolarization assay. 5 mM TCEP was added for the reaction of reduced tHNADS and no reducing agent was used for wild type or oxidized tHNADS. The data are presented as mean ± S.D., n = 3

In a parallel approach, we performed a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay to examine how the disulfide bridge affects the structure and stability of tHNADS (Supplementary Fig. 8). At neutral pH, the melting temperature (Tm) of the oxidized tHNADS, but not the reduced tHNADS, increased by ~15% relative to WT tHNA, indicating that the engineered disulfide bond stabilized tHNA. The Tm could not be measured at pH 4.6 for either WT tHNA or the reduced tHNADS due to high fluorescence intensity, because large hydrophobic surfaces in tHNA were exposed at acidic pH. However, the Tm of the oxidized tHNADS could be measured at pH 4.6, which only decreased by ~6% in comparison to the Tm at neutral pH, suggesting that the oxidized tHNADS is trapped in the neutral-pH-like conformation and insensitive to pH changes. These findings demonstrate that the BoNT-switch regulates the exposure of hydrophobic surface at acidic pH.

Using tHNADS as a unique molecular probe, we further examined lipid association of tHNA using a liposome co-sedimentation assay (Fig. 3b). The WT tHNA and the reduced tHNADS co-sedimented with anionic liposomes containing 20% DOPS at pH 4.6 in a lipid concentration-dependent fashion. In contrast, association of the oxidized tHNADS with liposomes was significantly reduced at all lipid concentrations tested. Furthermore, the oxidized tHNADS exhibited a marked decrease in both the rate of calcein dye release and the ability to dissipate the membrane potential of a polarized membrane in liposomes, while the reduced tHNADS behaved like the WT tHNA (Fig. 3c, d). These findings prove that the acidic pH induced structural change of the BoNT-switch is necessary for tHNA to transform from a water-soluble state to a transmembrane state.

The BoNT-switch regulates self-association of BoNT/A1

Since the tHNA homodimer observed in the crystal lattice could be affected by crystal packing, we used analytical size-exclusion chromatography to examine the effect of pH on self-association of tHNA in solution. We found that tHNA shifted to a higher oligomeric state at acidic pH ( < 5.4) in a concentration-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). Importantly, the oxidized tHNADS remained monomeric at pH 4.6, while the reduced form shifted to oligomers like the WT tHNA (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Therefore, tHNA self-association seems to be needed to protect the unique conformation of the BoNT-switch at acidic pH, whereas such protection could be provided by other BoNT domains in the context of the full-length toxin or by the vesicle membrane in vivo. Furthermore, the micromolar tHNA concentration used in this assay is much higher than the physiological concentration of BoNT/A1 at the neuromuscular junctions. Therefore, tHNA dimerization may not be directly relevant for BoNT/A1 function in vivo. In support of this, we found that the full-length BoNT/A1i (a genetically inactivated BoNT/A1 carrying R363A/Y366F mutations) does not exhibit pH-dependent self-association in solution (Supplementary Fig. 9d).

To investigate whether membrane binding may trigger BoNT/A1 self-association, we used single-molecule photobleaching to count the number of BoNT/A1 molecules recruited to single liposomes containing gangliosides. Photobleach step counting has been widely used to study protein oligomerization on the membrane51–53. Since BoNT/A1 contains several functionally important cysteine residues, we could not chemically-label BoNT/A1. To circumvent this, we fluorescently labeled a BoNT/A1-specific camelid heavy-chain-only antibody (ciA-D12) that binds to LC with high affinity (Kd ~0.2 nM) and does not affect BoNT/A1 function54. Importantly, the ciA-D12-BoNT/A1i interaction is not affected by acidic pH (Supplementary Fig. 10). An engineered cysteine residue (S142C) in ciA-D12 was labeled to > 99% efficiency with Alexa Fluor 647 maleimide (termed D12*). The D12*-BoNT/A1i complex was assembled and purified by size-exclusion chromatography.

The BoNT/A1i-D12* complex was reconstituted on 100 nm anionic liposomes containing 10% polysialoganglioside GT1b. The liposomes also contained 0.5 mol% biotin-labeled lipids to allow liposomes to be attached to a streptavidin-coated microscope slide while unbound proteins were washed away by rinsing. To allow co-localization of protein and liposomes, we included 0.5 mol% Rhodamine-labeled lipids and imaged the samples with two-color Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy. Liposomes were deposited under dilute conditions to achieve optical resolution of individual liposomes, which appeared as diffraction-limited spots (Fig. 4a). Under our incubation conditions (10 nM protein with 0.5 mg/mL lipid), we estimated that ~10% of liposomes were occupied by protein molecules. The low surface density and low liposome occupancy both help to minimize the probability of false co-localization of proteins.

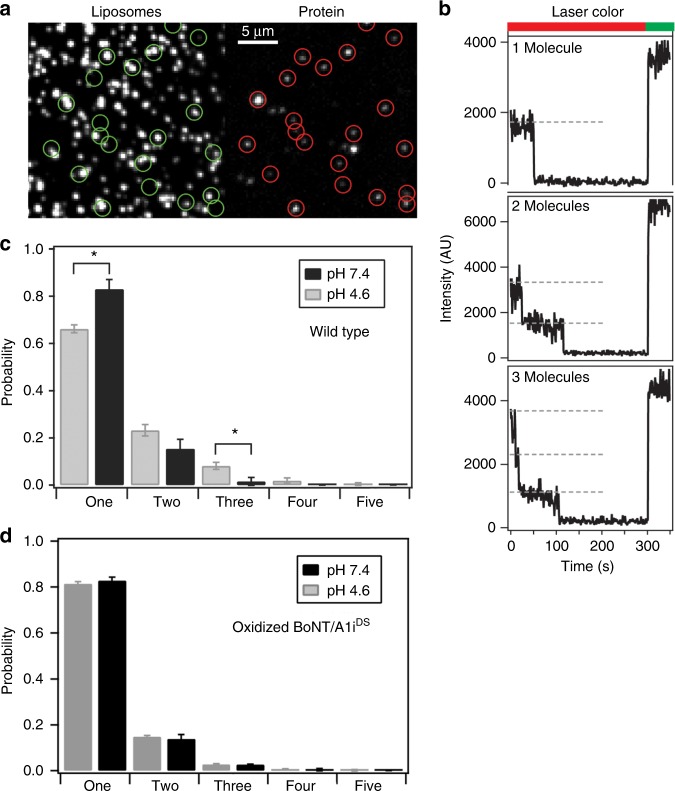

Fig. 4.

Single-molecule analysis of the distribution of BoNT/A1i on individual liposomes. a Representative TIRF microscope images showing co-localization of Alexa 647-labeled BoNT/A1i-D12* complexes (right) with rhodamine-labeled liposomes (left). In these experiments, < 10% of liposomes were occupied by protein to minimize co-localization. The circled spots on the right were used for photobleaching analysis only when co-localized with rhodamine fluorescence. b Representative time traces of fluorescence emission from spots used to assess the oligomerization state. The bar above the panel indicates the excitation with red laser used to first bleach the Alexa 647 followed by green laser to probe for rhodamine emission. Examples are shown for 1-, 2-, and 3-step photobleaching events. Dashed lines highlight individual bleaching steps. (c) Distribution of bleaching steps for BoNT/A1i-D12* at pH 4.6 (n = 935) and pH 7.4 (n = 482). The increase in 1-step events and decrease in 3-step events upon raising the pH to 7.4 were statistically significant (asterisk) with p = 0.0001 and 0.0065, respectively. The decrease in 2-step events was just above significance with p = 0.077. d Distribution of photobleaching steps for oxidized BoNT/A1iDS-D12* at pH 4.6 (n = 589) and pH 7.4 (n = 535). No significant differences were observed when the BoNT-switch was locked by a disulfide bond. Error bars indicate standard error of measurement (SEM) from replicate analysis

The number of BoNT/A1i-D12* complexes on a liposome was determined by counting Alexa Fluor 647 photobleaching steps for diffraction-limited spots that also contained Rhodamine emission (Fig. 4b). At pH 4.6, we found that a major fraction of BoNT/A1i-D12* fluorescent spots displayed single-step bleaching with a smaller fraction showing multi-step bleaching up to five steps (Fig. 4c). We observed 66.2 ± 1.7%, 23.2 ± 2.4%, 8.2 ± 1.5%, 1.9 ± 1.2%, and 0.5 ± 0.5% for one to five-step events, respectively. At neutral pH, we found a decrease in protein co-localization events. Specifically, two- and three-step events were reduced and higher order events disappeared entirely while the one-step bleaching events increased by 16.8 ± 3.8%. This finding suggests that, while BoNT/A1i binds to membranes predominantly as monomer at neutral or acidic pH on liposomes we tested here, an acidic environment increased the degree of BoNT/A self-association. Interestingly, low-pH-dependent self-association of BoNT was previously observed for BoNT/B on artificial membranes27.

To test whether locking the BoNT-switch could affect self-association of BoNT/A1 on membranes, we incorporated S622C and V653C into the full-length BoNT/A1i (termed BoNT/AiDS). BoNT/AiDS was oxidized and then assembled with the labeled antibody D12*. We found that the oxidized BoNT/A1iDS showed a similar liposome occupancy as the WT toxin, suggesting that locking the BoNT-switch did not significantly affect membrane association of BoNT/A1. We then examined the oligomerization state of BoNT/AiDS by analyzing the photobleaching time traces as described above. Notably, locking the BoNT-switch showed significant effect on oligomerization of the full-length toxin (Fig. 4d). The increase in protein oligomerization at pH 4.6 was completely eliminated in the oxidized BoNT/A1iDS, even though BoNT/A1iDS showed the same level of monomers at pH 7.4 as the WT toxin (82.8 ± 1.5%). Taken together, we found that acidic pH tends to promote BoNT/A1 oligomerization on liposomes, which is partly regulated by the BoNT-switch. The physiological relevance of BoNT/A1 self-association on the vesicle membrane in vivo warrants further investigation.

The BoNT-switch is crucial to the extreme potency of BoNT/A1

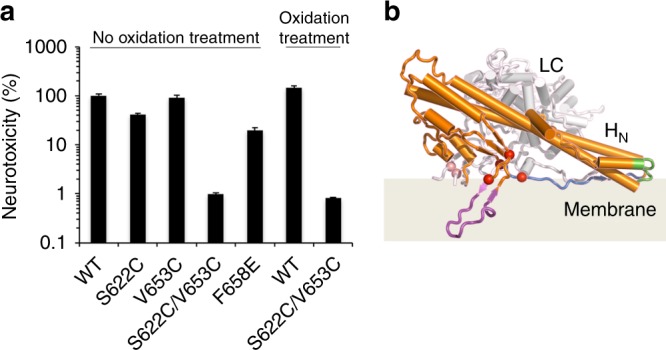

To explore the functional relevance of the BoNT-switch to BoNT toxicity, we incorporated the S622C and V653C mutations into active BoNT/A1 (termed BoNT/A1DS). Since an endogenous disulfide linkage between LC and HC is crucial to LC translocation55,56, we could not directly measure the toxicity of BoNT/A1DS under reducing conditions. Instead, we generated two single cysteine mutations (BoNT/A1S622C and BoNT/A1V653C) as controls. We then examined the neurotoxicity of BoNT/A1 mutants at motor nerve terminals using ex vivo mouse phrenic nerve hemidiaphragm (MPN) assays57 (Fig. 5a). Remarkably, the naturally oxidized BoNT/A1DS displayed a ~100-fold decreased toxicity, while BoNT/A1V653C and BoNT/A1S622C behaved like the WT toxin. When BoNT/A1DS was further oxidized with copper phenanthroline, the decrease in neurotoxicity was ~180-fold. BoNT/A1F658E has a ~5-fold decreased toxicity, which is likely due to the energetic costs of burying of an acidic residue in a hydrophobic pocket when tHNA transits into the acidic-pH conformation during LC translocation (Fig. 2b). These results prove that the structural change in the BoNT-switch as we observed in the crystal structure is essential to the extreme potency of BoNT/A1.

Fig. 5.

The BoNT-switch modulates neurotoxicity of BoNT/A1. a Neurotoxicity of BoNT/A1 variants was analyzed using the MPN assay. The paralytic half-times were determined and converted to the corresponding concentrations of wild-type BoNT/A1 using a concentration–response curve. The resulting toxicities were expressed relative to wild-type BoNT/A1 (n = 3–6, ± S.D.). b Proposed model for insertion of BoNT/A1 into lipid bilayer. The β2/β3 loop and the two putative membrane-interacting segments, F667–I685 and R827–R836, are colored in magenta, blue, and green, respectively. The inter-chain disulfide bond and four conserved carboxylates (D625, D629, E666, E670) are drawn as salmon and red spheres, respectively

Discussion

Like many other bacterial toxins and enveloped viruses, the capability of BoNT to trespass the endosomal membrane barrier is crucial for its function22,58. To achieve membrane insertion, these proteins commonly carry a buried hydrophobic segment as a molecular switch that is exposed only when the proteins sense the endosomal signals (e.g., acidic pH, enzymatic cleavage, membrane surface charges). Here, we identified such a molecular switch in BoNT/A1 that senses acidic environment and subsequently converts the water-soluble translocation domain into a membrane-competent state. We suggest that the highly conserved β2/β3 loop within the BoNT-switch may be the first part of HN to insert into the membrane (Fig. 5b). This model is supported by the observation that two previously proposed membrane-interacting segments of HNA (segments F667–I685 and R827–R836) and the conserved disulfide linkage between LC and HN56 are close to the β2/β3 loop33,34,43,44. Furthermore, conserved carboxylates (D625, D629, E666, and E670) that were suggested to sense acidic pH and interact with the anionic lipid in their protonated forms59 are positioned at the base of the β2/β3 loop, which would favorably interact with a negatively charged membrane at acidic pH.

Our model of membrane binding would require an acidic pH-triggered structural re-orientation of BoNT/A1 to position HNA on the membrane surface. Such a structural rearrangement is possible because the flexible HN-HC linker allows a 140o rotation between HN and HC when BoNT/A1 is bound to the nontoxic nonhemagglutinin (NTNHA) protein at pH < 6.5 in the medium progenitor toxin complex (M-PTC)60. The driving force for the structural change likely involves acidic pH and the electrostatic attraction between the electropositive surface of BoNT/A1 with the negatively charged membrane27. Interestingly, the HN-HC linker of TeNT is also modulated by pH, which may play a role in reorienting TeNT for the membrane insertion61. Furthermore, we speculate that the belt of BoNT/A1 may modulate the conformational change of HNA by interacting with and shielding the hydrophobic surface of the BoNT-switch. The belt is likely unfolded upon membrane binding and vesicle acidification that may help to release the BoNT-switch.

It is well known that some viral-fusion proteins, such as influenza virus hemagglutinin, vesicular stomatitis virus GP, and Ebola virus GP, contain a hydrophobic loop that is buried at neutral pH, but released at acidic pH to insert the fusion protein into the lipid bilayer3,46. Our complementary structural and functional studies reveal a surprising similarity between the β2/β3 loop of the BoNT-switch, which is conserved in almost all known BoNTs, and the IFL of Ebola virus GP2. Moreover, HNA carries a pair of long α-helices that resemble the coiled-coil viral-fusion proteins (e.g., influenza hemagglutinin and HIV-1 gp41)10. These viral proteins undergo dramatic structural reorganization of these helices after the fusion loop penetrates the membrane3,62,63. We speculate that the formation of protein-conducting channel of BoNT may similarly involve a large reorganization of the long helices within tHNA.

Interestingly, the β2/β3 loop of BoNT is situated at the middle of the long helices that likely break down into shorter helical segments following membrane insertion. In this scenario, our model may represent the first step of membrane insertion, in which the β2/β3 loop brings the long helices of HNA closer to the vesicle membrane and promotes its reorganization to form the translocation channel. Another possibility is that the β2/β3 loop may constitute part of the transmembrane hairpin and HNA may form β-hairpin channels reminiscent of anthrax toxin22. Formation of a β-hairpin channel requires oligomerization of BoNT, which is also consistent with our observation that acidic pH tends to promote BoNT/A1 oligomerization on liposomes, which is partly regulated by the BoNT-switch. It is worth noting that our data argues that the mechanism of BoNT membrane insertion is different from some other bacterial toxins, such as diphtheria toxin and colicin, which also have an α-helical translocation domain similar to BoNT. Those toxins do not have a viral-fusion-peptide-like switch, and they insert into membranes through exposure of a helical hairpin without a significant change in secondary structures64.

In summary, our studies demonstrate that BoNT/A1 contains a molecular switch that regulates channel formation and LC delivery, so it only happens in the right cellular location at the right time. The importance of the BoNT-switch to the neurotoxicity of BoNT/A1 suggests that blocking the conformational transition with an antibody or small molecule inhibitors holds promise as an alternative strategy to neutralize these extremely lethal toxins. This is also supported by a report that antibodies from the sera of some cervical dystonia patients with immune-resistance to BoNT/A1 bound to a region of BoNT/A1 (S659–G677) that is within the BoNT-switch65. These unique human antibodies are worthy of further characterization. Because of its functional importance and high sequence conservation among all known BoNTs, the BoNT-switch could be an ideal target for the development of the long sought-after cross-serotype therapeutic intervention for botulism.

Methods

Statistical method

No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and were not performed with blinding to the conditions of the experiments.

Construct design and cloning

The sequences corresponding to full-length BoNT/A1 carrying two substitutions at the active site (R363A/Y366F) (BoNT/A1i), and tHNA (residues K547–K871) from BoNT/A1-producing C. botulinum strain 62 A were cloned into expression vectors pGEX-6p-1 and pCDFduet-1, respectively. ciA-D12 was cloned into pGEX-6p-1. Sequences of PCR primers are provided in Supplementary Table 1. To facilitate protein purification, a His6-tag followed by a PreScission cleavage site was introduced to the N-terminus of tHNA. BoNT/A1i and ciA-D12 were produced with an N-terminal GST-tag followed by a PreScission cleavage site. All tHNA, BoNT/A1, BoNT/A1i, and ciA-D12 mutations were generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Agilent).

Protein expression and purification

All recombinant proteins were expressed in the E. coli strain BL21-RIL (DE3) (Novagen). Bacteria expressing BoNT/A1i and ciA-D12 were grown at 37 °C in LB medium in the presence of the appropriate selecting antibiotics. Expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-b-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) when OD600 reached 0.6. The temperature was then decreased to 16oC and expression was continued for 16 h. For the expression of tHNA, bacteria were grown at 37 °C in TB medium and expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG when OD600 reached 0.9. The temperature was then decreased to 19 °C and expression was continued for 16 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −20 °C until use.

For protein purification, bacteria were resuspended in Tris buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 400 mM NaCl) with 0.4 mM PMSF and lysed by sonication. His6-tagged proteins (tHNA wild type and mutants) were purified using a Ni-NTA (nitrilotriacetic acid, Qiagen) affinity column in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 400 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole and subsequently eluted in the same buffer containing 150 mM imidazole. The eluted fractions of each protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against a buffer composed of 20 mM Hepes (pH 8.0) and 50 mM NaCl, followed by His-tag removal using PreScission protease. The protein was further purified by MonoQ ion-exchange chromatography (GE Healthcare) in a buffer containing 20 mM Hepes (pH 8.0) and eluted with a NaCl gradient, followed by Superdex-75 size-exclusion chromatography (SEC; GE Healthcare, Germany) in 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0) and 150 mM NaCl. GST-tagged BoNT/A1i and the ciA-D12 were purified using Glutathione Sepharose 4B resins (GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 400 mM NaCl, and eluted from the resins after on-column cleavage using PreScission protease. The protein was further purified by Superdex-200 Increase or Superdex-75 SEC in 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0) and 150 mM NaCl for BoNT/A1i and ciA-D12, respectively. Each protein was concentrated to ~5 mg/ml using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (Millipore) and stored at −80 °C until used for further characterization or crystallization.

Wild type and mutated recombinant full-length activated BoNT/A1 were produced under biosafety level 2 containment (project number GAA A/Z 40654/3/123) recombinantly in K12 E. coli strain in Dr. Rummel’s lab66. BoNT/A1 variants carrying C-terminal His6-tag were purified on Co2+-Talon matrix (Takara Bio Europe S.A.S., France) and eluted with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole. For proteolytic activation, BoNT/A1 was incubated for 16 h at room temperature with 0.01 U bovine thrombin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Germany) per µg of BoNT/A1. Subsequent gel filtration (Superdex-200 SEC; GE Healthcare, Germany) was performed in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4).

The purified tHNADS and BoNT/A1DS were oxidized by copper 1,10-phenanthroline in vitro. Oxidation of the tHNADS mutant was confirmed by gel-shift analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7b).

The purified ciA-D12 (S124C) was labeled with Alexa Fluor C2 647 maleimide (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The labeled ciA-D12 was further purified by MonoQ ion-exchange chromatography in 10 mM Hepes (pH 8.0) and eluted with a NaCl gradient. The calculated dye to protein ratio was ~1 mole of dye per mole of ciA-D12. BoNT/A1i-ciA-D12 complex were prepared by mixing BoNT/A1i and ciA-D12 in 1:1.5 molar ratio and the complex was purified by size-exclusion chromatography using Superdex-200.

Crystallization

Initial crystallization screens were performed using a Phoenix crystallization robot (Art Robbins Instruments) and high-throughput crystallization screen kits (Hampton Research), followed by extensive manual optimization. The best single crystals of tHNA were grown at 18 °C by the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method. The protein at a concentration of 5 mg/ml was mixed in a 2:1 (v/v) ratio with a reservoir solution containing 1.4 M sodium potassium phosphate (pH 5.1) and 0.1 M potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate. Crystals of tHNAF658E were grown with a protein concentration at 3 mg/ml at 18 °C with a reservoir solution containing 2.4 M ammonium phosphate, 0.1 M Tris (pH 8.5), and 0.05 % n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside. The crystals of tHNA were cryoprotected in the original mother liquor supplemented with 30% (v/v) ethylene glycol. The crystals were dehydrated by air dry for 5 minutes and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. The crystals of tHNAF658E were cryoprotected with 2.5 M lithium sulfate.

Data collection and structure determination: After screening numerous crystals at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) or Advanced Photon Source (APS), the best X-ray diffraction datasets for tHNA and tHNAF658E crystals were collected at 100 K at beam line BL9-2, SSRL. The data were processed with iMOSFLM67. Data collection statistics are summarized in Table 1. The structure of tHNA or tHNAF658E was determined by molecular replacement using the Phaser software68 with tHNA of BoNT/A1 as the search model (PDB code 3V0A)60. Manual model building and refinement was performed in COOT69, PHENIX70, and CCP4 suite71 in an iterative manner. The refinement progress was monitored with the free R value using a 5% randomly selected test set72. The structures were validated through the MolProbity73 and showed excellent stereochemistry. Structural refinement statistics are listed in Table 1. Residues 858–871 of chain A and residue 871 of chain B of tHNA and residues 647–649 of tHNAF658E are invisible in the electron density map that likely indicates local flexibility. One and nine phosphate molecules were identified in the crystal structures of tHNA and tHNAF658E, respectively, that could be attributed to the high phosphate concentration in the corresponding crystallization buffer. All structure figures were prepared with PyMol (http://www.pymol.org).

8-anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid binding assay

The wild type or mutant tHNA was incubated at 0.1 mg/ml (~2.68 μM) with 100 μM ANS for ten minutes in either 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.0–5.6), 50 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 6.2), or 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.0). All buffers contained 100 mM NaCl. Fluorescence spectra were recorded at 25 °C in a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M2e spectrophotometer with excitation at 370 nm. The emission spectrum was collected from 420 to 640 nm. The fluorescence intensity was corrected by subtraction of background fluorescence from ANS in buffer lacking protein. Fluorescence emission was calculated as the area under the spectra. Error bars indicate SD of three replicate measurements.

Thermal denaturation assay

The thermal stability of wild type or mutant tHNA was measured using a fluorescence-based thermal shift assay on a StepOne real-time PCR machine (Life Technologies). Immediately before the experiment, the protein (2.7 μM) was mixed with the fluorescent dye SYPRO Orange (Sigma-Aldrich) at pH 7.0 or pH 4.6. The samples were heated from 25 °C to 90 °C in ~45 min. The midpoint of the protein-melting curve (Tm) was determined using the analysis software provided by the instrument manufacturer. The data obtained from three independent experiments were averaged to generate the bar graph. The Tm of tHNA wild type and reduced tHNADS at pH 4.6 is not determined due to high fluorescence signal at starting temperature.

Analytical size-exclusion chromatography

tHNA at protein concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1 mg/ml (~2.7–27 μM) were incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes in various buffers that contained 0.1 M NaCl and either 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.4–5.6) or 50 mM Hepes (pH 7.4). BoNT/A1i at 4 mg/ml (27 μM) was incubated in buffers at pH 4.4 or pH 7.4. Reduced tHNADS was prepared by pre-incubation with 5 mM TCEP. Protein oligomerization was resolved using Superdex-200 SEC.

Liposome co-sedimentation assays

Liposomes were prepared by extrusion method using Avanti Mini Extruder according to manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, lipids (Avanti Polar Lipid) were dissolved in chloroform while GT1b trisodium salt (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was dissolved in methanol. The lipids at the indicated molar ratios were mixed and then dried under nitrogen gas and placed under vacuum for at least 2 h. The dried lipids were rehydrated and were subjected to five rounds of freezing and thawing cycles. Unilamellar vesicles were prepared by extrusion through a 100 nm pore membrane using an Avanti Mini Extruder according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To study the pH-dependence of tHNA–lipid association, 0.2 μM protein was incubated with 0.15 mg/ml asolectin liposomes (Sigma-Aldrich) in 150 mM NaCl with either 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.4–5.0) or 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5) at room temperature for 2 h. The samples were centrifuged at 160,000× g for 40 min. The supernatant was removed and the pellets were resuspended twice in the same buffer and were re-centrifuged. Liposome-bound proteins were analyzed by comparing the supernatant and pellet fractions on SDS-PAGE.

Effect of lipid composition on tHNA–lipid binding was studied by mixing 0.27–2.7 μM of tHNA with 0.1 mg/ml liposome containing either 60% L-α-phosphatidylcholine (PC), 40% cholesterol; 60% L-α-phosphatidylserine (PS), 40% cholesterol; or 30% PC, 30% PS, 40% cholesterol (Encapsular Nano Sciences). The protein–liposome mixture was incubated in 0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.4) at room temperature for 2 h and centrifuged.

The effect of disulfide formation in the BoNT-switch on tHNA–lipid binding was studied by a low-centrifugal field protocol as described using vesicles containing 1-oleoyl-2-(9,10-dibromostearoyl)phosphatidylcholine (OBPC)74. OBPC has density of 1.2 g/cm3 and sediments easily in relatively low centrifugal field75. A volume of 0.2 μM tHNA or mutants were incubated with liposomes composed of 80% OBPC and 20% DOPS in 0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.6), 1 mM KCl, and 1 mM EDTA at room temperature for 2 h. The samples were spun progressively at 4000×, 9000×, and 16,000× g for 30 min each. Supernatant and pellet were separated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Calcein dye release assay

Dried lipid (20 mg/ml) was resuspended in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM calcein. Free calcein dye was separated from calcein-entrapped liposomes by desalting (Zeba). Fluorescence was measured on a Spectramax M2e cuvette module with excitation at 493 nm and emission at 525 nm. In the assay, liposomes were diluted either in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.6), 1 mM EDTA, or in 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 1 mM EDTA to give a final concentration of 0.2 mM and incubated until the fluorescence signal was stable. Wild type or mutant tHNA was added at 0.2 μM and the fluorescence intensity was recorded for 10 minutes. The reaction was stopped by adding 0.1% Trion X100. The percentage of fluorescence change was calculated as the ((F − Finitial) / Ffinal).

Membrane depolarization assay

Depolarization was measured as previously described with some modifications36. Briefly, liposomes composed of 70% DOPC, 20% DOPS, 10% cholesterol were prepared in 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0). To create a trans–positive membrane potential ( + 135 mV), liposomes were diluted in 200 mM KCl, 1 mM NaCl with either 10 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.6–5.8) or 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0). Membrane potential was monitored using 6 μM ANS. ANS is sensitive to membrane potential and has been used as a measure of the magnitude of the diffusion potential37. ANS is strongly fluorescent when bound to lipids and gives an additional increase in fluorescence intensity when a trans–positive potential is present. Valinomycin was added at time 0-second to give a final concentration of 30 nM. At 180-second, wild type, or mutant tHNA were added at 0.2 μM and the fluorescence intensity at 490 nm was monitored for 3 minutes with excitation at 380 nm. The experiments were repeated three times independently.

Mouse phrenic nerve hemidiaphragm assay

The MPN assay was performed employing 20–30 g NMRI mice (Janvier SA, France) as described previously19,57. According to §4 Abs. 3 (killing of animals for scientific purposes, German animal protection law (TSchG)), animals were sacrificed by trained personnel before dissection of organs and its number reported yearly to the animal welfare officer of the Central Animal Laboratory and to the local authority, Veterinäramt Hannover. First, mice were euthanized by CO2 anesthesia and subsequent exsanguination via an incision of the ventral aspect of the throat. The chest of the cadaver was opened, the phrenic nerve hemidiaphragm tissue was explanted and placed into an organ bath. The phrenic nerve was continuously stimulated at 5–25 mA with a frequency of 1 Hz and with a 0.1 ms pulse duration. Isometric contractions were transformed using a force transducer and recorded with VitroDat Online software (FMI GmbH, Germany). The time required to decrease the amplitude to 50% of the starting value (paralytic half-time) was determined. To allow comparison of the altered neurotoxicity of mutants with BoNT/A1 wild type, a power function (y(BoNTA1; 0.75, 1.5, 3.0, 6.0 pM) = 98.536 × −0.267, R2 = 0.9693) was fitted to a concentration–response curve consisting of four concentrations determined in 3–5 technical replicates. Resulting paralytic half-times of the BoNTA1 mutants were converted to concentrations of the wild type employing the above power functions and finally expressed as relative neurotoxicity.

Single-molecule analysis of oligomerization

ciA-D12 construct was kindly provided by Dr. Charles B. Shoemaker54. ciA-D12 contains two buried cysteines that are inaccessible for labeling. An additional cysteine (S124C) was introduced into ciA-D12 through site-directed mutagenesis. Purified ciA-D12 was labeled with Alexa-647 maleimide (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and subsequently purified with cation exchange. The labeling efficiency was determined to be over 99% using UV-Vis spectroscopy. BoNT/A1i was expressed and purified as described above. The complexes with D12* were prepared by incubating with a 1.5-fold excess of D12*. Free D12* was removed by Superdex-200 SEC.

Liposomes containing 10% GT1b, 69% DOPC, 20% DOPS, 0.5% rhodamine-PE, and 0.5% biotin-PE were prepared by extrusion through a 100 nm pore membrane. To form proteoliposomes, 10 nM BoNT/A1i–D12* or oxidized BoNT/A1iDS–D12* was incubated with 0.5 mg/ml lipid at room temperature for 1 h at the pH indicated. The mixture was then diluted 1000-fold and incubated for 5 minutes in a passivated, quartz microscope chamber functionalized with streptavidin. The biotinylated liposomes were retained and unbound proteins are washed away by exhaustive rinsing with buffer. At the low densities needed for optical resolution of individual liposomes, we could observe sufficient liposomes for statistical analysis, while minimizing the probability that a diffraction-limited spot would contain multiple liposomes. Samples were imaged using a prism-based Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscope. Samples were first excited with a laser diode at 640 nm (Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA) to photobleach Alexa 647-labeled BoNT/A1i–D12* or BoNT/A1iDS-D12* molecules followed by excitation with a diode pumped solid state laser at 532 nm (Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA) to probe for Rhodamine-labeled liposomes. Emission from protein and lipids was separated using an Optosplit ratiometric image splitter (Cairn Research Ltd., Faversham UK) containing a 645 nm dichroic mirror, a 585/70 band pass filter for Rhodamine, and a 670/30 band pass filter for Alexa 647 (all Chroma, Bellows Falls, VT). The replicate images were relayed to a single iXon EMCCD camera (Andor Technologies, Belfast, UK) at a frame rate of 10 Hz. Data were processed in MATLAB to cross-correlate the replicate images and extract time traces for diffraction-limited spots with intensity above baseline. Single-molecule traces were hand selected based on the exhibition of single-step decays to baseline during 640 illumination and the appearance of Rhodamine emission during 532 illumination.

SAXS data collection and analysis

Purified tHNA was exchanged into a buffer containing 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 55 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), and the protein samples were concentrated to 10 mg/ml. SEC-SAXS experiment was performed using Bio-SAXS beam line BL4-2 at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) in a similar manner to our previous report76. Experimental setup and structural parameters are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Briefly, the program SasTool (http://ssrl.slac.stanford.edu/~saxs/analysis/sastool.htm) was employed for data reduction to generate background-subtracted scattering profiles. The script fplcplots, implemented in the program AUTORG77, was used for consecutive Guinier analysis and assessing data quality. Sample was eluted as a sharp peak and no significant radiation damage or concentration dependence was observed during the elution. The theoretical scattering curve from an atomic structure (tHNA of PDB code 3BTA) was computed and was fitted with experimental data using the program CRYSOL78. Ab initio modeling was performed using the program DAMMIF79 and the averaged and filtered model from 20 independent ab initio models was generated by the program DAMAVER80.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) grants R01AI091823, R01AI125704, and R21AI123920 to R.J.; and by the Swiss Federal Office for Civil Protection BABS #353005630 to A.R. and R01MH081923 to M.E.B. NE-CAT at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) is supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41 GM103403). The Pilatus 6M detector on 24-ID-C beam line is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205). Use of the APS, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393).

Author contributions

K.-h.L. and R.J. conceived the project. A.R., N.K. and J.W. generated the active full-length BoNT/A1 variants and performed the MPN assay. G.Z. and M.E.B performed the single particle counting. T.M. carried out the SAXS measurements. K.P. collected the X-ray diffraction data. K.L., R.J., M.E.B. and A.R. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all other authors.

Data availability

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for tHNA and tHNAF658E have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 6DKK [10.2210/pdb6DKK/pdb] and 6 MHJ [10.2210/pdb6MHJ/pdb], respectively. All relevant data are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-07789-4.

References

- 1.Young JAT, Collier RJ. Anthrax toxin: receptor binding, internalization, pore formation, and translocation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ladokhin A. pH-triggered conformational switching along the membrane insertion pathway of the diphtheria toxin T-domain. Toxins (Basel) 2013;5:1362–1380. doi: 10.3390/toxins5081362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Virology. 2015;479-480:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruenberg J, Van Der Goot FG. Mechanisms of pathogen entry through the endosomal compartments. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:495–504. doi: 10.1038/nrm1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossetto O, Pirazzini M, Montecucco C. Botulinum neurotoxins: genetic, structural and mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12:535–549. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigalke H. Botulinum toxin: application, safety, and limitations. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013;364:307–317. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-33570-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigalke H, Rummel A. Medical aspects of toxin weapons. Toxicology. 2005;214:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peck MW, et al. Historical perspectives and guidelines for botulinum neurotoxin subtype nomenclature. Toxins. 2017;9:38. doi: 10.3390/toxins9010038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nestorovich EM, Bezrukov SM. Obstructing toxin pathways by targeted pore blockage. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:6388–6430. doi: 10.1021/cr300141q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lacy DB, Tepp W, Cohen AC, DasGupta BR, Stevens RC. Crystal structure of botulinum neurotoxin type A and implications for toxicity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:898–902. doi: 10.1038/2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swaminathan S, Eswaramoorthy S. Structural analysis of the catalytic and binding sites of Clostridium botulinum neurotoxin B. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:693–699. doi: 10.1038/78005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanetti G, et al. Inhibition of botulinum neurotoxins interchain disulfide bond reduction prevents the peripheral neuroparalysis of botulism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015;98:522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunger AT, et al. Botulinum neurotoxin heavy chain belt as an intramolecular chaperone for the light chain. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1191–1194. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao G, et al. N-linked glycosylation of SV2 is required for binding and uptake of botulinum neurotoxin A. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016;23:656–662. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam KH, Yao G, Jin R. Diverse binding modes, same goal: the receptor recognition mechanism of botulinum neurotoxin. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2015;117:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin R, Rummel A, Binz T, Brunger AT. Botulinum neurotoxin B recognizes its protein receptor with high affinity and specificity. Nature. 2006;444:1092–1095. doi: 10.1038/nature05387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montecucco C. How do tetanus and botulinum toxins bind to neuronal membranes? Trends Biochem. Sci. 1986;11:314–317. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(86)90282-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rummel A. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2017;406:1–37. doi: 10.1007/82_2016_48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strotmeier J, et al. Identification of the synaptic vesicle glycoprotein 2 receptor binding site in botulinum neurotoxin A. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montal M. Translocation of botulinum neurotoxin light chain protease by the heavy chain protein-conducting channel. Toxicon. 2009;54:565–569. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer A, Montal M. Molecular dissection of botulinum neurotoxin reveals interdomain chaperone function. Toxicon. 2013;75:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang J, Pentelute BL, Collier RJ, Hong Zhou Z. Atomic structure of anthrax protective antigen pore elucidates toxin translocation. Nature. 2015;521:545–549. doi: 10.1038/nature14247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peraro MD, Van Der Goot FG. Pore-forming toxins: ancient, but never really out of fashion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:77–92. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eswaramoorthy S, Kumaran D, Keller J, Swaminathan S. Role of metals in the biological activity of clostridium botulinum neurotoxins. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2209–2216. doi: 10.1021/bi035844k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiavo G, Boquet P, DasGupta BR, Montecucco C. Membrane interactions of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins: a photolabelling study with photoactivatable phospholipids. J. Physiol. Paris. 1990;84:180–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montecucco C, et al. Interaction of botulinum and tetanus toxins with the lipid bilayer surface. Biochem. J. 1988;251:379–383. doi: 10.1042/bj2510379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun S, et al. Receptor binding enables botulinum neurotoxin B to sense low pH for translocation channel assembly. Cell. Host. Microbe. 2011;10:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montecucco C, Schiavo G, Dasgupta BR. Effect of pH on the interaction of botulinum neurotoxins A, B and E with liposomes. Biochem. J. 1989;259:47–53. doi: 10.1042/bj2590047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puhar A, Johnson EA, Rossetto O, Montecucco C. Comparison of the pH-induced conformational change of different clostridial neurotoxins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;319:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Araye A, et al. The translocation domain of botulinum neurotoxin A moderates the propensity of the catalytic domain to interact with membranes at acidic pH. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0153401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer A, Sambashivan S, Brunger AT, Montal M. Beltless translocation domain of botulinum neurotoxin A embodies a minimum ion-conductive channel. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:1657–1661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.319400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galloux M, et al. Membrane interaction of botulinum neurotoxin A translocation (T) domain: the belt region is a regulatory loop for membrane interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:27668–27676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mushrush DJ, et al. Studies of the mechanistic details of the pH-dependent association of botulinum neurotoxin with membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:27011–27018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.256982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oblatt‐Montal M, Yamazaki M, Nelson R, Montal M. Formation of ion channels in lipid bilayers by a peptide with the predicted transmembrane sequence of botulinum neurotoxin A. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1490–1497. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fischer A, Mushrush DJ, Lacy DB, Montal M. Botulinum neurotoxin devoid of receptor binding domain translocates active protease. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000245. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Menestrina G, Forti S, Gambale F. Interaction of tetanus toxin with lipid vesicles. Effects of pH, surface charge, and transmembrane potential on the kinetics of channel formation. Biophys. J. 1989;55:393–405. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82833-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shiver JW, Donovan JJ. Interactions of diphtheria toxin with lipid vesicles: determinants of ion channel formation. Biochim. Et. Biophys. Acta. 1987;903:48–55. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(87)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pirazzini M, et al. On the translocation of botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins across the membrane of acidic intracellular compartments. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sankaranarayanan S, Ryan TA. Real-time measurements of vesicle-SNARE recycling in synapses of the central nervous system. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:197–204. doi: 10.1038/35008615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bas DC, Rogers DM, Jensen JH. Very fast prediction and rationalization of pKa values for protein-ligand complexes. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 2008;73:765–783. doi: 10.1002/prot.22102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masuyer G, et al. Crystal structure of a catalytically active, non-toxic endopeptidase derivative of Clostridium botulinum toxin A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009;381:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cavallo L, Kleinjung J, Fraternali F. POPS: A fast algorithm for solvent accessible surface areas at atomic and residue level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3364–3366. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wimley WC, White SH. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:842–848. doi: 10.1038/nsb1096-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lebeda FJ, Olson MA. Structural predictions of the channel-forming region of botulinum neurotoxin heavy chain. Toxicon. 1995;33:559–567. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(94)00192-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JE, Saphire EO. Ebolavirus glycoprotein structure and mechanism of entry. Future Virol. 2009;4:621–635. doi: 10.2217/fvl.09.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gregory SM, et al. Structure and function of the complete internal fusion loop from Ebolavirus glycoprotein 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104760108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dover N, Barash JR, Hill KK, Xie G, Arnon SS. Molecular characterization of a novel botulinum neurotoxin type H gene. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;209:192–202. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang S, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel botulinum neurotoxin. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14130. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang S, et al. Identification of a botulinum neurotoxin-like toxin in a commensal strain of enterococcus faecium. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:169–176.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brunt J, Carter AT, Stringer SC, Peck MW. Identification of a novel botulinum neurotoxin gene cluster in Enterococcus. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:310–317. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weninger K, Bowen ME, Choi UB, Chu S, Brunger AT. Accessory proteins stabilize the acceptor complex for synaptobrevin, the 1:1 Syntaxin/SNAP-25 Complex. Structure. 2008;16:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ulbrich MH, Isacoff EY. Subunit counting in membrane-bound proteins. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:319–321. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Groulx N, McGuire H, Laprade R, Schwartz JL, Blunck R. Single molecule fluorescence study of the Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Aa reveals tetramerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:42274–42282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.296103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukherjee J, et al. A novel strategy for development of recombinant antitoxin therapeutics tested in a mouse botulism model. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fischer A, Montal M. Crucial role of the disulfide bridge between botulinum neurotoxin light and heavy chains in protease translocation across membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29604–29611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pirazzini M, Rossetto O, Bolognese P, Shone CC, Montecucco C. Double anchorage to the membrane and intact inter-chain disulfide bond are required for the low pH induced entry of tetanus and botulinum neurotoxins into neurons. Cell Microbiol. 2011;13:1731–1743. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bigalke H, Rummel A. Botulinum neurotoxins: Qualitative and quantitative analysis using the mouse phrenic nerve hemidiaphragm assay (MPN) Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:4895–4905. doi: 10.3390/toxins7124855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leka O, et al. Diphtheria toxin conformational switching at acidic pH. Febs. J. 2014;281:2115–2122. doi: 10.1111/febs.12783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pirazzini M, et al. Neutralisation of specific surface carboxylates speeds up translocation of botulinum neurotoxin type B enzymatic domain. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:3831–3836. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gu S, et al. Botulinum neurotoxin is shielded by NTNHA in an interlocked complex. Science. 2012;335:977–981. doi: 10.1126/science.1214270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Masuyer G, Conrad J, Stenmark P. The structure of the tetanus toxin reveals pH-mediated domain dynamics. EMBO Rep. 2017;18:1306–1317. doi: 10.15252/embr.201744198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bullough PA, Hughson FM, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weissenhorn W, Carfí A, Lee KH, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the Ebola virus membrane fusion subunit, GP2, from the envelope glycoprotein ectodomain. Mol. Cell. 1998;2:605–616. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Popoff MR. Clostridial pore-forming toxins: powerful virulence factors. Anaerobe. 2014;30:220–238. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dolimbek BZ, Aoki KR, Steward LE, Jankovic J, Atassi MZ. Mapping of the regions on the heavy chain of botulinum neurotoxin A (BoNT/A) recognized by antibodies of cervical dystonia patients with immunoresistance to BoNT/A. Mol. Immunol. 2007;44:1029–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weisemann J, et al. Generation and characterization of six recombinant botulinum neurotoxins as reference material to serve in an international proficiency test. Toxins (Basel). 2015;7:5035–5054. doi: 10.3390/toxins7124861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Battye TGG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AGW. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brünger AT. Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures. Nature. 1992;355:472–475. doi: 10.1038/355472a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.White SH, Wimley WC, Ladokhin AS, Hristova K. Protein folding in membranes: determining energetics of peptide-bilayer interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1998;295:62–87. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(98)95035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wimley WC, et al. Folding of β-sheet membrane proteins: a hydrophobic hexapeptide model. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;277:1091–1110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matsui T, et al. Structural basis of the pH-dependent assembly of a botulinum neurotoxin complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2014;426:3773–3782. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Petoukhov MV, Konarev PV, Kikhney AG, Svergun DI. ATSAS 2.1—Towards automated and web-supported small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:s223–s228. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807002853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MH. CRYSOL—A program to evaluate X-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1995;28:768–773. doi: 10.1107/S0021889895007047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Franke D, Svergun DI. DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009;42:342–346. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Volkov VV, Svergun DI. Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. in. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003;36:860–864. doi: 10.1107/S0021889803000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for tHNA and tHNAF658E have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 6DKK [10.2210/pdb6DKK/pdb] and 6 MHJ [10.2210/pdb6MHJ/pdb], respectively. All relevant data are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files.