Summary

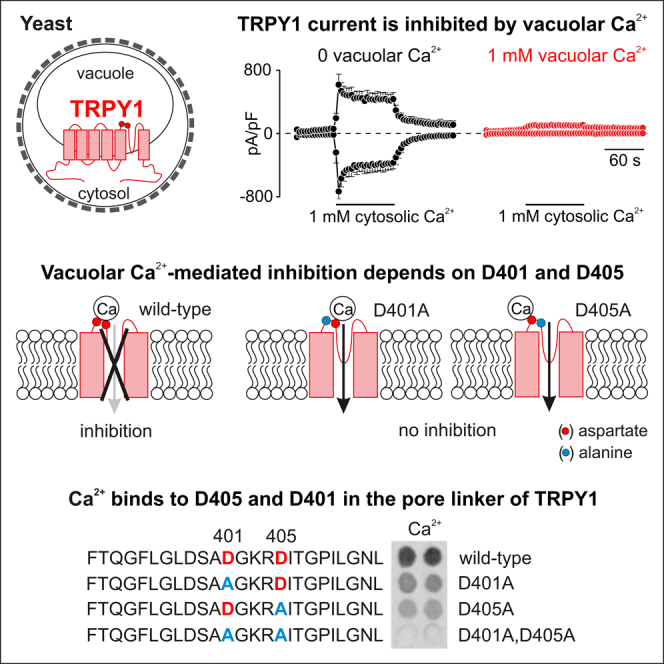

By vacuolar patch-clamp and Ca2+ imaging experiments, we show that the yeast vacuolar transient receptor potential (TRPY) channel 1 is activated by cytosolic Ca2+ and inhibited by Ca2+ from the vacuolar lumen. The channel is cooperatively affected by vacuolar Ca2+ (Hill coefficient, 1.5), suggesting that it may accommodate a Ca2+ receptor that can bind two calcium ions. Alanine scanning of six negatively charged amino acid residues in the transmembrane S5 and S6 linker, facing the vacuolar lumen, revealed that two aspartate residues, 401 and 405, are essential for current inhibition and direct binding of 45Ca2+. Expressed in HEK-293 cells, a significant fraction of TRPY1, present in the plasma membrane, retained its Ca2+ sensitivity. Based on these data and on homology with TRPV channels, we conclude that D401 and D405 are key residues within the vacuolar vestibule of the TRPY1 pore that decrease cation access or permeation after Ca2+ binding.

Subject Areas: Structural Biology, Protein Structure Aspects, Biophysics

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

The yeast vacuolar TRPY1 channel is inhibited by vacuolar Ca2+

-

•

Aspartate residues D401A and D405A are essential for Ca2+-mediated inhibition

-

•

Aspartate residues D401 and D405 are essential for direct Ca2+ binding

-

•

Ca2+ binding to D401 and D405 within vacuolar pore vestibule mediates inhibition

Structural Biology; Protein Structure Aspects; Biophysics

Introduction

The transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channel family is encoded by more than 100 genes (Venkatachalam and Montell, 2007). With the exception of the Ca2+-selective TRPV5 and TRPV6 the TRP channels are non-selective cation channels sharing the membrane topology of six transmembrane helices (S1–S6) and N- and C-terminal domains residing within the cytosol. By mediating cation influx, TRP channels shape the membrane potential and increase the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]cyt), translating environmental and endogenous stimuli into cellular signals. Most TRP channels fulfill their physiological function in the plasma membrane as cation influx channels, whereas some functional TRP channels are localized in the membrane of cytoplasmic organelles (Berbey et al., 2009, Chen et al., 2014, Dong et al., 2008, Lange et al., 2009, Oancea et al., 2009, Turner et al., 2003).

Calcium ions permeate TRP channels - with the exception of the Ca2+-impermeable TRPM4 and TRPM5 - and also potentiate, activate, or inhibit currents most probably by interfering with TRP channel domains facing the cytosol (Blair et al., 2009, Bodding et al., 2003, Doerner et al., 2007, Du et al., 2009, Gross et al., 2009, Launay et al., 2002, McHugh et al., 2003, Olah et al., 2009, Prawitt et al., 2003, Starkus et al., 2007, Voets et al., 2002, Watanabe et al., 2003, Xiao et al., 2008, Zurborg et al., 2007). Likewise the TRP channel TRPY1, encoded by the vacuolar conductance 1 (YVC1) gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and localized in the vacuolar membrane, is activated by Ca2+ interfering with cytosolic channel domains (Bertl and Slayman, 1990, Palmer et al., 2001, Wada et al., 1987). TRPY1 mediates vacuolar Ca2+ release, and the amount of cytosolic [Ca2+] required for TRPY1 activation can be substantially lowered in the presence of reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT), glutathione, or β-mercaptoethanol (Bertl et al., 1992b, Bertl and Slayman, 1990). In addition to Ca2+, TRPY1 is also permeable to monovalent cations (permeability ratio PCa/PK ∼5; Bertl and Slayman, 1992), revealing a single-channel conductance of more than 300 pS in 180 mM KCl (Chang et al., 2010, Palmer et al., 2001, Wada et al., 1987, Zhou et al., 2003). TRPY1 is suggested to be involved in the response to hyperosmotic and oxidative stress as well as glucose-induced Ca2+ signaling (Bertl and Slayman, 1990, Bouillet et al., 2012, Denis and Cyert, 2002, Palmer et al., 2001). However, the exact function of the TRPY1-mediated Ca2+ release is still elusive.

Binding of Ca2+ by some mammalian TRP channels including the Ca2+-activated TRPM4 has been described to be mediated by four coordinating residues within S2 and S3 close to the cytosolic S2-S3 linker (Autzen et al., 2018). These residues are not conserved in the TRPY1 sequence. All mammalian TRPs and the fly's TRPL are binding Ca2+/calmodulin in vitro, and Bertl et al. (Bertl et al., 1992b, Bertl et al., 1998a, Bertl et al., 1998b) suggested that Ca2+/calmodulin contributes to TRPY1 activation in yeast, but a negative charge cluster, D573DDD576, within the TRPY1's cytosolic C-terminus was shown to be crucial for the Ca2+-mediated activation of TRPY1 (Su et al., 2009).

In the present study, we characterized the dependence of TRPY1 current inhibition and activation on vacuolar and cytosolic [Ca2+] by patch-clamp recordings from yeast vacuoles and Ca2+ imaging in yeast. By alanine scanning and direct 45Ca2+ binding, we identified two aspartate residues within the S5-S6 linker facing the vacuolar lumen to be essential for Ca2+ binding and Ca2+-dependent inhibition of the TRPY1 current.

Results

Cytosolic Ca2+ Activates the Vacuolar TRPY1 Channel

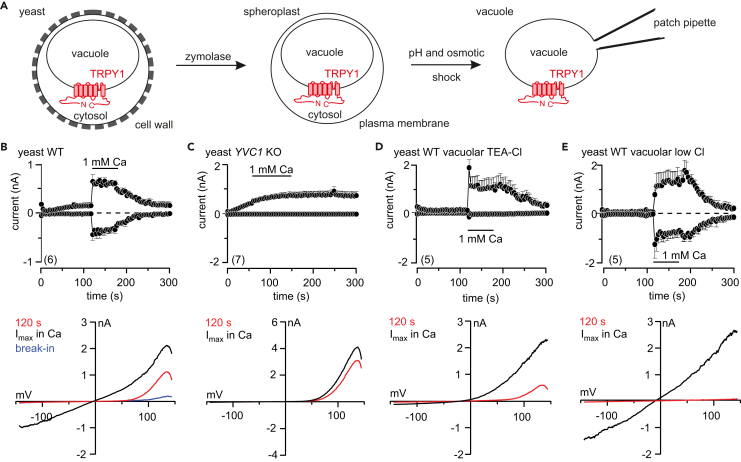

To get electrophysiological access to the yeast vacuole, the cell wall and membrane have to be removed (Figure 1A). At break-in and application of voltage ramps (150 to −150 mV), a small voltage-dependent outward rectifying current was recorded at membrane potentials above 80 mV (Figure 1B, bottom, blue current-voltage relation [IV]). Membrane potentials refer to the cytosolic side, and inward currents are defined as cation flow across the vacuolar membrane into the cytosol (Bertl et al., 1992a). Upon perfusion of the 150 mM KCl pipette solution, i.e., washout of vacuolar content, the outward current increases to maximum amplitude within 120 s (Figure 1B, red IV). Application of 1 mM cytosolic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]cyt) activates additional inward and outward currents (Figure 1B, Imax in Ca), which are absent in vacuoles isolated from YVC1 knockout cells (YVC1 KO; Figure 1C). These currents are carried by cations, as their inward portion disappears in the absence of vacuolar (pipette) K+ substituted by TEA+ (tetraethylammonium) (Figure 1D). In contrast, the voltage-dependent outward rectifying current appearing after break-in is carried by Cl−, as substitution of vacuolar Cl− by gluconate significantly reduces its amplitude (Figure 1E, red IV). TRPY1 inward and outward cation currents were already detectable at [Ca2+]cyt of 10 μM (Figures 2A and 2B), and Ca2+ non-cooperatively (Hill coefficient < 1) increased currents in a concentration-dependent manner with apparent EC50 values of 498 μM for the inward current and 391 μM for the outward current (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Cytosolic Ca2+ Activates Cation Conductance in Yeast Vacuoles via TRPY1

(A) Procedure to release the yeast vacuole for patch-clamp experiments.

(B–E) Inward currents at −80 mV and outward currents at 80 mV, extracted from 200-ms ramps (0.5 Hz) spanning from 150 to −150 mV, Vh = 0 mV, plotted versus time (top), and corresponding current-voltage relations (IVs) at break-in (blue), after 120 s (red) and at maximum current (Imax) in 1 mM cytosolic Ca2+ (black; bottom) measured in isolated vacuoles from wild-type (WT; B, D, and E) and YVC1-deficient (YVC1 KO; C) yeast. The membrane potentials refer to the cytosolic side, i.e., inward currents represent movement of positive charges from the vacuole toward the cytosol (Bertl et al., 1992a). 1 mM Ca2+ was applied to the bath (representing the cytosol) as indicated by the bars. In (D) K+ and in (E) Cl− were substituted by TEA+ (tetraethylammonium) and gluconate in the patch pipette, respectively. Currents and IVs are shown as means ± SEM and just means, respectively, with the number of measured cells indicated in brackets.

Figure 2.

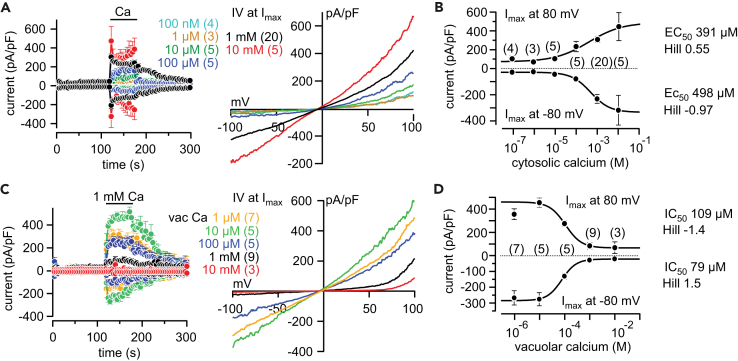

Concentration-Dependent Activation of Yeast Vacuolar TRPY1 by Cytosolic Ca2+ and Inhibition by Vacuolar Ca2+

(A–D) Inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, respectively, extracted from 200-ms ramps (0.5 Hz) spanning from 150 to −150 mV, Vh = 0 mV, plotted versus time (A and C, left), and corresponding IVs at maximum currents (Imax, A and C, right) activated by diverse cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]cyt, A and B) and 1 mM [Ca2+]cyt at the indicated vacuolar Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]vac, vac Ca, corresponding to the [Ca2+] in the patch pipette, C and D) in isolated vacuoles from wild-type yeast. Application of Ca2+ is indicated by the bar. In (B), maximal inward currents (at −80 mV) and outward currents (at 80 mV) are plotted versus the [Ca2+]cyt concentration. The sigmoidal fits reveal EC50 values of 498 and 391 μM [Ca2+]cyt for half-maximal activation of the inward and outward currents (B), respectively. In (D), currents at −80 and 80 mV activated by 1 mM [Ca2+]cyt are plotted versus the [Ca2+]vac. The sigmoidal fits reveal half-maximal inhibition by [Ca2+]vac of 79 and 109 μM for the inward and outward currents (D), respectively. Currents are normalized to the size of the vacuole (pA/pF) and shown as means ± SEM (A–D) and means (IVs in A and C), with the number of measured cells indicated in brackets.

See also Figures S1 and S2.

Vacuolar Ca2+ Inhibits TRPY1 Activity

To characterize the dependence of TRPY1 currents on vacuolar [Ca2+], we perfused the vacuole with 1 mM Ca2+ by the patch pipette. The currents activated by 1 mM [Ca2+]cyt were significantly reduced (Figures 2C and 2D). Figure 2C shows the vacuolar [Ca2+]-dependent inhibition of TRPY1 currents activated by 1 mM [Ca2+]cyt with apparent IC50 values of 79 μM for the inward current and 109 μM for the outward current (Figure 2D). We consistently found Hill coefficients > 1 (1.4–1.5, Figure 2D) suggesting that the channel is inhibited by the cooperative binding of two molecules of Ca2+. Inhibition of TRPY1 currents by vacuolar Ca2+ is still prominent at a pH value of 5.5 (Figure S1), considering the slightly acidic pH in the yeast vacuole (Preston et al., 1989).

Sr2+, Ba2+, and Mn2+ substitute for Ca2+ in TRPY1 activation (when present at the cytosolic site) and inhibition (when present at the vacuolar site) (Figure S2). In the absence of vacuolar Ca2+ ([Ca2+]vac), cytosolic concentrations of 1 mM divalent cations increased activation in the order Sr2+ (12%) < Mn2+ (15%) < Ba2+ (63%) with 100% current activation at 1 mM [Ca2+]cyt (Figures S2A and S2B). At 100% current activation (1 mM [Ca2+]cyt, and 0 [Ca2+]vac), vacuolar concentrations of 1 mM divalent cations inhibited in the order Mn2+ (33%) < Ba2+ (63%) < Sr2+ (68%) < Ca2+ (96%) (Figures S2C and S2D).

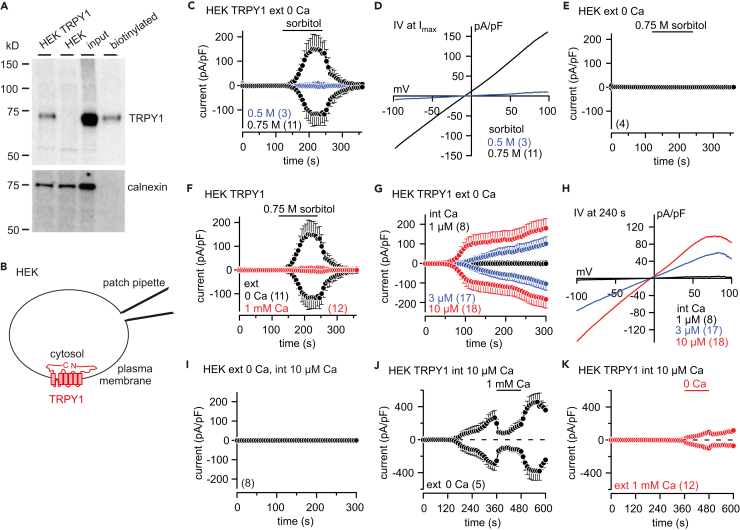

In HEK-293 Cells TRPY1 Retains Its Ca2+-Dependent Properties

In yeast, TRPY1 was shown to be also activated by hyperosmotic shock, i.e., in the presence of high extracellular concentrations of sorbitol or NaCl (Zhou et al., 2003). Hyper- or hypoosmotic shock induces shrinkage or swelling of the vacuole, respectively, which easily disrupts the whole-vacuolar patch-clamp configuration. To prove whether hyperosmotic shock-induced TRPY1 activity is also inhibited by Ca2+, we expressed the YVC1 cDNA in HEK-293 cells. As shown by western blot the TRPY1 protein is present in transfected cells and a significant fraction is detectable in the plasma membrane by surface biotinylation (Figure 3A). In the plasma membrane the channel regions facing the vacuole in yeast are now facing the extracellular bath, whereas, like in yeast, the N-terminus, C-terminus, S2-S3, and S4-S5 linkers are facing the cytoplasm (Figure 3B). As shown in Figures 3C and 3D, TRPY1 currents are activated in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ by increasing the osmolarity in the bath by application of 0.5 and 0.75 M sorbitol, whereas no currents were detectable in non-transfected HEK-293 cells (Figure 3E). Applying 1 mM Ca2+ to the bath significantly reduced the TRPY1 current induced by 0.75 M sorbitol (Figure 3F, red trace) indicating that TRPY1 integrates activating and inhibitory stimuli also in HEK-293 cells.

Figure 3.

Ca2+-Dependent Regulation of TRPY1 Currents in Transfected HEK-293 Cells

(A) Western blot of protein lysates from YVC1 cDNA-transfected (HEK TRPY1) and non-transfected (HEK) HEK-293 cells. Biotinylation of surface proteins shows that a considerable fraction of TRPY1 present in transfected HEK-293 cells (input) resides in the plasma membrane (biotinylated). The filter was stripped and incubated in the presence of an antibody directed against the intracellular protein calnexin as control.

(B) Orientation of TRPY1 (red) in the plasma membrane with N- and C-termini residing within the cytosol.

(C–K) Inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV, extracted from 400-ms ramps (0.5 Hz) spanning from −100 to 100 mV, Vh = 0 mV, plotted versus time (C, E–G, and I–K) and corresponding IVs (D and H) of maximum currents (Imax) from (C) or at 240 s from (G), activated by 0.5 or 0.75 M sorbitol (hyperosmotic shock; C–F) or indicated [Ca2+]cyt (int Ca; buffered with BAPTA; G-K) at 0 or 1 mM external (ext) Ca2+ in HEK TRPY1 cells (HEK TRPY1; C, D, F–H, J, and K) or non-transfected HEK-293 cells (HEK; E and I). The bars indicate application of 0.5 or 0.75 M sorbitol in C, E, and F, or 0 and 1 mM Ca2+-containing bath solution in K and J, respectively. The black traces in C and F are the same. Currents and IVs are normalized to the cell size (pA/pF) and are shown as means ± SEM (C, E–G, and I–K) and means (D and H) with the number of measured cells in brackets.

In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, TRPY1 inward and outward currents in HEK-293 cells are activated by [Ca2+]cyt (at 3 and 10 μM; Figures 3G and 3H), confirming the assumed orientation of TRPY1 in the plasma membrane. Non-transfected HEK-293 cells do not reveal any significant currents under these conditions (Figure 3I). TRPY1 currents activated by 10 μM [Ca2+]cyt in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ are readily inhibited when 1 mM Ca2+ was added (Figure 3J). Figure 3K shows that in the presence of 1 mM external Ca2+, almost no TRPY1 current appeared at [Ca2+]cyt of 10 μM, whereas after removal of external Ca2+ a significant current developed (Figure 3K).

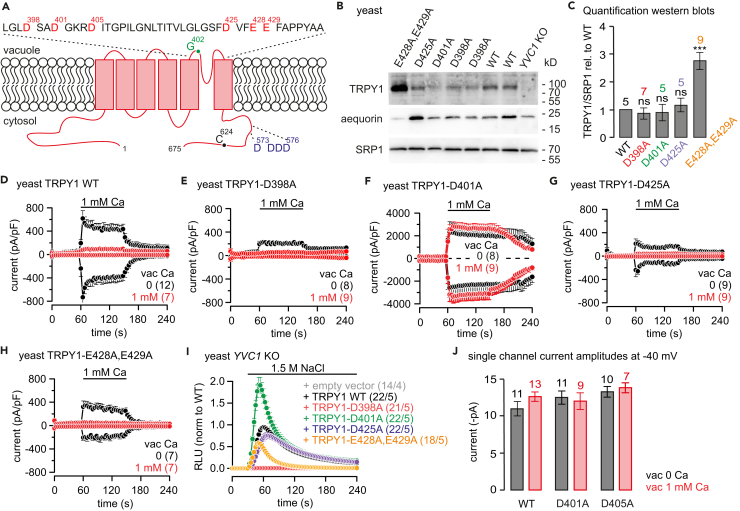

Aspartate Residues 401 and 405 Mediate the Ca2+-Dependent Inhibition of TRPY1

The mechanism of the inhibition of TRPY1 currents by vacuolar Ca2+ in yeast or extracellular Ca2+ in HEK-293 cells was not known. We noticed six negatively charged acidic residues in the S5-S6 linker contributing to the TRPY1 pore, D398, D401, D405, D425, E428, and E429 (Figure 4A), which we replaced by alanine residues. The cDNAs of all mutants and of wild-type TRPY1 (plasmids see Table 1) were expressed in YVC1 KO yeast (Chang et al., 2010). Wild-type and mutant proteins are detectable in western blot (Figure 4B). Only the transformation of yeast with plasmid pRS316-TRPY1D405A did not yield any colonies. Figures 4D–4H show currents of wild-type TRPY1 (Figure 4D) and of the TRPY1 mutants, expressed in YVC1 KO yeast (Figures 4E–4H), activated by 1 mM [Ca2+]cyt in the absence (Ca 0) or presence of 1 mM vacuolar Ca2+. As shown for vacuoles of wild-type yeast cells (Figure 2) 1 mM [Ca2+]cyt activates TRPY1 in the absence (Figure 4D, black trace), but not in the presence of vacuolar Ca2+ (Figure 4D, red trace), whereas TRPY1D398A failed to yield currents even in the absence of vacuolar Ca2+ (Figure 4E). The Ca2+-mediated outward current detectable in the absence of vacuolar Ca2+ most probably reflects changes of the vacuolar chloride conductance (see Figure 1). Expression of TRPY1D401A yielded a small constitutive current (Figure S3A, green trace), which could be significantly enhanced by 1 mM [Ca2+]cyt, leading to current amplitudes more than five times higher than mediated by wild-type TRPY1 (Figure 4F, black trace), but currents were no longer inhibited by vacuolar Ca2+ (Figure 4F, red trace). Beside smaller current amplitudes, TRPY1D425A and TRPY1E428A,E429A revealed the same Ca2+ dependence as TRPY1 wild-type (Figures 4G and 4H). Ca2+ imaging experiments obtained after expressing the cytosolic luminescent Ca2+ reporter aequorin in intact yeast confirmed the patch-clamp data (Figure 4I). TRPY1D401A induced the highest cytosolic Ca2+ increase upon hyperosmotic shock, whereas TRPY1D398A did not respond at all. Current-voltage relationships and statistics of whole-vacuole current amplitudes and yeast cytosolic Ca2+ signals are summarized in Figure S3. The reversal potential of vacuolar currents did not vary between TRPY1 mutants and wild-type, arguing against changes of ion permeability.

Figure 4.

Vacuolar TRPY1 Currents in YVC1 KO Yeast Expressing Wild-Type or Mutant YVC1 cDNAs

(A) Predicted transmembrane topology of the yeast vacuolar TRPY1 (675 amino acid residues) with negative charge cluster at the cytosolic C-terminus assumed to be responsible for TRPY1 activation (blue) (Su et al., 2009) and negatively charged residues within the S5-S6 linker facing the vacuolar lumen (red). The TRPY1G402S mutant (green) is constitutively active (Zhou et al., 2007), and the TRPY1C624S mutant (black) can no longer be activated by 2-mercaptoethanol (Hamamoto et al., 2018).

(B) Western blot of protein lysates from non-transformed yeast (YVC1 KO) or YVC1 KO yeast transformed with wild-type (WT) and mutant YVC1 cDNAs (as indicated). Filter was stripped and incubated with antibodies for aequorin (middle) and SRP1 (serine-rich protein; bottom) as controls.

(C) Antibody stain intensities of TRPY1 proteins in (B) were quantified relative to the antibody stain of the endogenous serine-rich protein 1 (SRP1) and normalized to the WT TRPY1/SRP1 ratio (summary of five independent western blots). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA): not significant (ns), ∗∗∗ p<0.001 compared to WT.

(D–H) Whole-vacuole currents at −80 and 80 mV extracted from 200-ms ramps (0.5 Hz) spanning from 150 to −150 mV, Vh = 0 mV, plotted versus time, activated by cytosolic Ca2+ (1 mM) at 0 (black) or 1 mM (red) vacuolar (vac, patch pipette) Ca2+ in YVC1 KO cells expressing WT ( D) or mutant (E–H) YVC1 cDNAs.

(I) Changes of cytosolic Ca2+ challenged by 1.5 M NaCl (hyperosmotic shock) monitored in transformed YVC1 KO yeast cells (as in D–H) as relative luminescence units (RLU). Bars indicate application of 1 mM Ca2+ (D–H) or 1.5 M NaCl (I).

(J) Single-channel current amplitudes of TRPY1WT, TRPYD401A, and TRPY1D405A in the absence and presence of vacuolar 1 mM Ca2+, analyzed at −40 mV from current traces of voltage ramps and voltage steps in whole vacuoles and excised (outside-out) vacuolar patches. Single channels of TRPY1D405A were analyzed from yeast cells transfected with single-copy pRS316 CEN plasmids without its own promoter (see Figure S4C). Currents are normalized to the size of the vacuole (pA/pF) and shown as means ± SEM with number of measured vacuoles (D–H) or the number of experiments (x) from y independent transformation (x/y; (I) indicated in brackets. Single-channel current amplitudes in (J) are shown as means ± SEM with number of independent experiments indicated. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revelead no differences.

See also Figures S3 and S4.

Table 1.

TRPY1 Plasmids Generated in the Laboratories of the Authors and Used in This Study

| Plasmid | TRPY1 Construct |

|---|---|

| Backbone: Yeast single-copy centromeric pRS316 vector | |

| pGS2062 | TRPY1 wild-type |

| pSB276 | TRPY1D398A |

| pSB277 | TRPY1D401A |

| pSB278 | TRPY1D405A |

| pSB279 | TRPY1D425A |

| pSB280 | TRPY1E428A,E429A |

| Backbone: Bicistronic eukaryotic expression (HEK-293 cells) | |

| pCAGGS-YVC1-IRES-GFP | TRPY1 wild-type |

| pCAGGS-YVC1D398A-IRES-GFP | TRPY1D398A |

| pCAGGS-YVC1D401A-IRES-GFP | TRPY1D401A |

| pCAGGS-YVC1D405A-IRES-GFP | TRPY1D405A |

| pCAGGS-YVC1D425A-IRES-GFP | TRPY1D425A |

| pCAGGS-YVC1E428A,E429A-IRES-GFP | TRPY1E428A,E429A |

The YVC1 gene encoding wild-type TRPY1 (NCBI accession number NM_001183506.1) was subcloned into the single-copy centromeric pRS316 vector (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989) under control of its own promoter and termination sequence. For some transformations (Figures S4A–S4C) the latter sequences were omitted. The eukaryotic expression vector pCAGGS has been described (Wissenbach et al., 2001).

Wild-type and mutant YVC1-transformed YVC1 KO yeast showed different amplitudes of vacuolar currents and cytosolic Ca2+ signals: D401A revealed larger currents and higher [Ca2+]cyt than wild-type TRPY1, whereas for TRPY1D425A and TRPY1E428A,E429A, currents and changes of [Ca2+]cyt were smaller (Figures 4D–4I). Western blots revealed similar amounts of TRPY1 protein in yeast transformed with wild-type, D398A, D401A, and D425A YVC1, relative to the endogenous SRP1, used as a control (Figure 4C). The higher amount of TRPY1E428A,E429A protein (Figure 4C) not mirrored by larger currents (Figure 4H) and higher [Ca2+]cyt (Figure 4I) might indicate that only part of the protein detectable in western blot is targeted to the vacuolar membrane.

Transformation of yeast with pRS316-YVC1D405A did not yield any colonies. To yield lower expression levels to prevent delirious effects of overexpression, we cloned the YVC1 gene (wild-type, YVC1D401A, and YVC1D405A) in single-copy pRS316 CEN plasmids without its own promoter. Under these conditions, cytosolic Ca2+-induced vacuolar currents were recorded from YVC1 wild-type and YVC1D401A- and YVC1D405A-transformed YVC1 KO yeast (Figures S4A–S4C). In contrast to wild-type TRPY1 (Figure S4A), the currents induced by cytosolic Ca2+ remained in the presence of 1 mM vacuolar Ca2+ in TRPY1D401A (Figure S4B; note the spontaneous current after break-in) and TRPY1D405A (Figure S4C).

Beside a smaller current amplitude of TRPY1D405A at 40 mV in the absence of vacuolar 1 mM Ca2+ (see Figure S4E), neither the mutations D401A and D405A nor the presence of vacuolar 1 mM Ca2+ significantly affected single-channel current amplitudes of TRPY1 analyzed at −40 and 40 mV (Figures 4J and S4E, respectively; example traces are shown in Figure S4D). Single-channel current amplitudes of TRPY1D405A were analyzed from yeast cells transfected with single-copy pRS316 CEN plasmids without its own promoter (see above). The unchanged single-channel current amplitude (Figures 4J and S4E) but significantly reduced whole-vacuolar current amplitude (Figure 4D) in wild-type TRPY1 suggests a prominent decrease of the open probability in the presence of vacuolar 1 mM Ca2+.

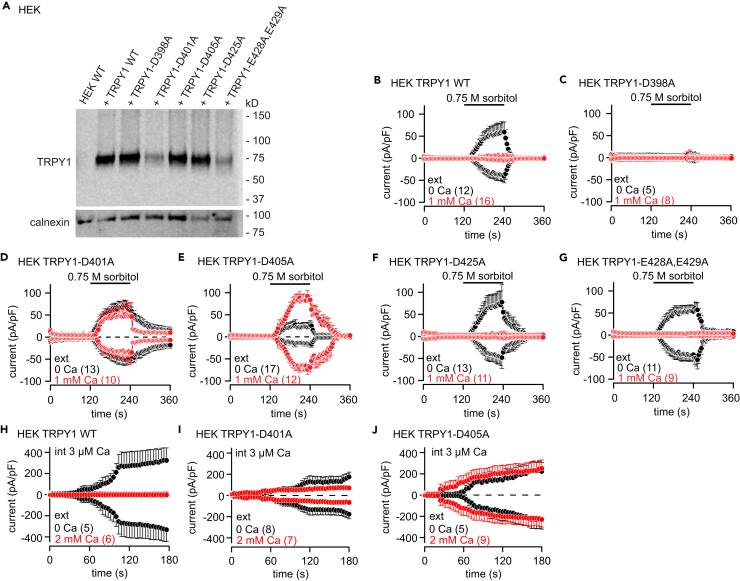

After expression of wild-type and mutant YVC1 cDNAs (plasmids see Table 1) in HEK-293 cells, all proteins including TRPY1D405A were detectable (Figure 5A), and we recorded hyperosmotic shock (Figures 5B–5G) as well as cytosolic Ca2+-induced currents (Figures 5H–5J). Current-voltage relationships and statistics of whole-cell current amplitudes are summarized in Figure S5. Compared with wild-type TRPY1 (Figure 5B) hyperosmotic shock did not initiate TRPY1D398A currents (Figure 5C), but the TRPY1D425A (Figure 5F) and TRPY1E428A,E429A mutants (Figure 5G) behaved like wild-type TRPY1, very similar as observed in the yeast vacuole (Figure 4). Like in yeast vacuoles TRPY1D401A yielded spontaneous currents (Figures 5D and S5A, green trace), and, compared with wild-type TRPY1 (Figures 5B and 5H), extracellular Ca2+ (1 and 2 mM, respectively) did not inhibit hyperosmotic shock and cytosolic Ca2+-induced activity of the mutant channels TRPY1D401A and TRPY1D405A (Figures 5D, 5I, 5E, and 5J). The latter mutant induced even larger current amplitudes upon hyperosmotic shock in the presence of extracellular Ca2+. Current-voltage relationships and statistics of current amplitudes are summarized in Figure S5.

Figure 5.

Wild-Type and Mutant TRPY1 Currents Recorded from HEK-293 Cells

(A) Western blot of protein lysates from non-transfected HEK-293 cells (HEK WT) and HEK-293 cells transfected with the YVC1 wild-type (+ TRPY1 WT) and the mutant YVC1 cDNAs as indicated. The filter was stripped and incubated with an antibody for calnexin as loading control (bottom panel).

(B–J) Inward and outward currents at −80 and 80 mV extracted from 400-ms ramps (0.5 Hz) spanning from −100 to 100 mV, Vh = 0 mV, plotted versus time, activated by 0.75 M sorbitol (bar, hyperosmotic shock; B–G) or 3 μM cytosolic Ca2+ (H–J) at 0 (black), 1 (B–G), or 2 mM (H–J) external Ca2+ (red) in HEK-293 cells transiently transfected with WT (B and H) or mutant (C–G, I, and J) YVC1 cDNAs. Currents are normalized to the cell size (pA/pF). Data are shown as means ± SEM with the number of measured cells in brackets.

See also Figure S5.

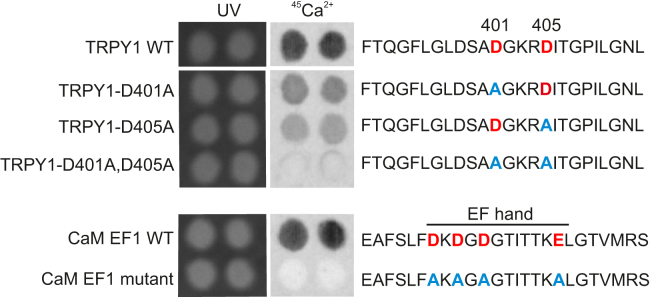

To prove whether residues D401 and D405 are required for Ca2+ binding 25-amino-acid (25-mer) peptides derived from wild-type (amino acid residues F390 to L414) and D401A and D405A mutant S5-S6 linkers of TRPY1 were synthesized and spotted onto hardened cellulose membranes and incubated with 45Ca2+ (Figure 6). The wild-type peptide significantly binds 45Ca2+, whereas the TRPY1D401A and TRPY1D405A peptides showed less and the double mutant (TRPY1D401A,D405A) no detectable 45Ca2+ binding. As control, we spotted a 25-mer peptide representing the first EF hand (EF1) of mammalian calmodulin (CaM; Figure 6). The 45Ca2+ binding by EF1 was completely abolished when its glutamate residues were replaced by alanine residues (Figure 6). The amounts of 45Ca2+ bound by EF1 and TRPY1F390-L414 are very similar, as estimated by the signals' intensities. Considering equal amounts of spotted 25-mer peptides (about 16 nmoles per spot), additionally estimated by UV absorption at 312 nm (Figure 6), close apparent binding affinities of the peptides for Ca2+ might be assumed. At physiological salt concentration, the non-cooperative Ca2+ binding affinity of the isolated CaM EF1 was estimated to be about 125 μM (Ye et al., 2005), which is very close to the value of 79–109 μM measured here for vacuolar Ca2+-dependent inhibition of TRPY1 (Figure 2D).

Figure 6.

Ca2+ Binding of TRPY1

Autoradiographs of 45Ca2+ binding by the 25-mer peptides derived from wild-type (amino acid residues F390 to L414) and D401A and D405A mutant S5-S6 linkers of TRPY1 (upper panel) and by the 25-mer peptides representing wild-type and mutant calmodulin EF hand 1 (CaM EF1, lower panel) as control (two out of four performed blots are shown). Peptides were synthesized and spotted onto hardened cellulose membranes (about 16 nmoles per spot) and incubated with 1.5 μM (1 mCi/L) 45Ca2+. Amounts of peptides spotted were additionally estimated by UV absorption at 312 nm. Aspartate (D) residues are marked in red and alanine (A) residues replacing aspartates are marked in blue. See also Figure S6.

Discussion

We performed whole-vacuole patch-clamp recordings and Ca2+ imaging experiments in yeast to study the Ca2+ dependence of TRPY1 using as controls a YVC1-deficient yeast strain (Chang et al., 2010) and HEK-293 cells heterologously expressing the YVC1 cDNA as functional TRPY1 channels in the plasma membrane. We show that inhibition of vacuolar TRPY1 is cooperatively mediated by the vacuolar [Ca2+] (IC50 79–109 μM), that it requires two aspartate residues (D401 and D405) in the S5-S6 linker facing the vacuolar lumen, and that these aspartate residues are directly involved in Ca2+ binding. The yeast vacuolar TRP cation channel TRPY1 may be assumed as a progenitor of TRP channels present in mammals, flies, and worms and underlies cation movements across the yeast vacuolar membrane. Additional TRP-related proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae like FLC2, encoded by the YAL053W gene, seem to be involved in endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release (Rigamonti et al., 2015). TRPY1 is activated by osmotic stress (Batiza et al., 1996, Denis and Cyert, 2002, Zhou et al., 2003), reducing agents (Bertl and Slayman, 1990, Wada et al., 1987), aromatic compounds like indole (John Haynes et al., 2008), and cytosolic Ca2+ (Bertl and Slayman, 1990, Wada et al., 1987). In the presence of DTT the EC50 values of TRPY1 activation by cytosolic Ca2+ are 498 μM (inward current) and 391 μM (outward current) with Hill coefficients < 1. Reducing agents such as DTT or β-mercaptoethanol lower the [Ca2+]cyt required for channel activation (Bertl and Slayman, 1990, Bertl and Slayman, 1992), and the cysteine residue 624 within TRPY1's C terminus facing the cytosol (Figure 4A) has been suggested to be involved in this process (Hamamoto et al., 2018). Reducing agents may mimic the redox environment in the yeast cytosol (Carpaneto et al., 1999, Lopez-Mirabal and Winther, 2008, Palmer et al., 2001), which might contribute to TRPY1 activation under certain conditions. Vacuolar TRPY1 currents are already activated at [Ca2+]cyt of 10 μM of cytosolic Ca2+ (Figure 2 and Bertl et al., 1992b, Bertl and Slayman, 1990, Bertl and Slayman, 1992), but the yeast [Ca2+]cyt has been estimated to be in the range of 260 nM (Halachmi and Eilam, 1989). Probably, hyperosmotic shock represents the initial physiological stimulus in intact yeast, which increases cytosolic Ca2+, which in turn facilitates TRPY1 activity. Palmer et al. (Palmer et al., 2001) suggested that the cytosolic activation of TRPY1 is Ca2+ specific, but we also detected activation by the alkaline earths Ba2+ > Sr2+ and by the transition metal ion Mn2+ (Figure S2).

High [Ca2+] within the vacuolar lumen presumably inhibits TRPY1 currents (Zhou et al., 2003), and 1 mM Ca2+ added to the bath eliminates TRPY1 single-channel currents in inside-out excised vacuolar patch-clamp recordings (Hamamoto et al., 2018). The present study shows that vacuolar Ca2+, as well as Sr2+ and Ba2+, strongly inhibit TRPY1 activity and that the amino acid residues D401 and D405 located in the vacuolar loop between S5 and S6 (Figure 4A) are crucial for Ca2+-dependent inhibition and direct Ca2+ binding. Mutation of the nearby G402 (Figure 4A) renders TRPY1 constitutively active (Zhou et al., 2007), indicating the significance of this area for proper gating. Hamamoto et al. described that luminal Zn2+ increased TRPY1 currents in vacuolar excised patches (Hamamoto et al., 2018). Zn2+ might be attracted to a single negatively charged residue and thereby prevent efficient coordination of Ca2+. In mouse TRPV3 and TRPV4, corresponding residues D641 and D682, respectively, were shown to be key residues for extracellular Ca2+-mediated channel inhibition (Voets et al., 2002, Watanabe et al., 2003, Xiao et al., 2008), and human TRPV1 D646 was suggested to be a high-affinity binding site for cations (Garcia-Martinez et al., 2000). However, D646 and D682 are part of the selectivity filter in TRPV1 and TRPV4, respectively (Deng et al., 2018, Liao et al., 2013), and, by sequence comparison, rather align to TRPY1D425 (Figure S6), whereas TRPY1D401 and TRPY1D405 are located in the vacuolar vestibule of TRPY1's ion-conducting pore. The residues E600, D601, E610, and E648 are involved in pH-dependent modulation of human TRPV1 (Jordt et al., 2000), with TRPV1D601 aligning to TRPY1D401 (Figure S6A). Although nothing is known about external Ca2+-mediated inhibition of TRPV1 and TRPV6, their S5-S6 linkers appear closer related to TRPY1 than TRPV3, TRPV4, TRPV2, and TRPA1 by sequence alignment (Figure S6A). TRPV6 residues D517 and E518, located in the upper vestibule and aligning with TRPY1D401, are shown to bind and guide Ca2+ into the channel pore of TRPV6 (Singh et al., 2017).

The structure of TRPY1 is not yet available. Therefore, we aligned the structure of TRPY1 according to the published structure of Xenopus tropicalis TRPV4 (Deng et al., 2018), which is inhibited by Ca2+ from the extracellular side (see above; Figures S6B and S6C). Our data show that TRPY1 D401 and D405 are decisive for the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of the channel. Both residues, D401 and D405, also highly conserved in TRPY homologs of other fungi (Ihara et al., 2014), are part of the outer pore domain of the channel and orientated to the lumen of the vacuole and are directly involved in Ca2+ binding. The alignment suggests that binding of Ca2+ to residues D401 and D405 might result in a reorientation of residues I455 and Y458, possibly involved in forming the lower gate of TRPY1, and thereby narrowing or occluding the lower gate (Figure S6B). According to the model, replacing D401 and D405 by alanine residues disables Ca2+ binding and thus prevents such structural changes in the presence of vacuolar Ca2+ (Figure S6C). As single-channel current amplitudes of TRPY1 are not affected (Figure 4J), we assume that Ca2+ binding to D401 and D405 affects the open probability by rearranging the main S6 segment, stabilizing a closed inactivated conformation of the channel by narrowing and occluding the lower gate.

The physiological pH value in yeast vacuoles is slightly acidic (Pearce et al., 1999, Preston et al., 1989). Vacuolar pH 6.0 does not alter the mechanosensitivity of TRPY1 (Zhou et al., 2003), whereas the current activated by cytosolic Ca2+ was reduced at a vacuolar pH 5.5, but the vacuolar Ca2+-dependent inhibition remained (Figure S1). The mammalian TRP channels TRPML1, 2, and 3 are located in endolysosomes, and thus exert their functions also in a cytoplasmic organelle environment as TRPY1. TRPML channels are involved in the release of Ca2+ and Fe2+ into the cytosol (Cheng et al., 2010), and TRPML1 has been shown to be regulated by lysosomal Ca2+ and pH (Cantiello et al., 2005, Li et al., 2017). Like for wild-type TRPY1 a significant fraction of the constitutively active TRPML1 mutant, TRPML1V432P, can be expressed in the plasma membrane of HEK-293 cells. Extracellular Ca2+ inhibits TRPML1V432P channel activity with an apparent IC50 of 270 μM (Li et al., 2017), which is in the range of the vacuolar [Ca2+], which inhibits TRPY1 (Figure 2). External (lysosomal) acidification reduced the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of TRPML1V432P, and an electronegative luminal pore domain was indicated as a unique hallmark of TRPML1's interaction site for lysosomal Ca2+ and H+ (Li et al., 2017).

The yeast vacuolar Ca2+ concentration was estimated to be 1.3 mM (Halachmi and Eilam, 1989, Iida et al., 1990) and the vacuole was assumed to function as a Ca2+ store with TRPY1 as Ca2+ release channel (Denis and Cyert, 2002). According to our results TRPY1 currents would be inhibited at 1.3 mM Ca2+, but a considerable amount of Ca2+ is bound by vacuolar polyphosphate (Dunn et al., 1994) and therefore most probably not available for channel inhibition. The remaining vacuolar free [Ca2+] of ∼30 μM (Dunn et al., 1994) would allow significant TRPY1 currents (Figure 2). Considering that monovalent cations K+ and Na+ are the major charge carriers used to record TRPY1 currents in the yeast vacuole and in HEK-293 cells, Ca2+ storage and release may not represent major functions of vacuoles and TRPY1 channels. Instead, upon hypertonic shock, which activates TRPY1, cation efflux from the vacuole might provide osmolytes to the cytosol and thereby counteracts water deprivation. The vacuolar Ca2+-dependent inhibition of TRPY1 might protect the yeast cell from cytosolic Ca2+ overload after hyperosmotic-shock-induced channel activation and increase of the vacuolar [Ca2+] subsequent to loss of vacuolar water.

Limitations of the Study

We studied the Ca2+-dependent modulation of the yeast vacuolar TRP channel and identified two aspartate residues in the outer vestibule as essential for Ca2+ binding and Ca2+-dependent inhibition. The structure of TRPY1 is not yet known, and we aligned the S5, pore linker, and S6 structure of TRPY1 according to the published structure of Xenopus TRPV4. Thus the mechanism we discuss for the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of TRPY1 reflects our experimental data along with a TRPY1 model, obtained due to an alignment to the available structure of another TRP protein. The suggested scenario awaits further support by structural data of TRPY1.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Wesely, Stefanie Caesar, Heidi Löhr, Karin Wolske, and Martin Simon-Thomas for excellent technical assistance; Yiming Chang for the YVC1-deficient yeast strain and initial preparation of vacuoles; and Stefanie Buchholz and Ulrich Wissenbach for cloning of YVC1 plasmids.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) RTG 1326 (M.A., G.S., V.F., A. Beck), Collaborative Research Center (DFG/SFB) 894 (A. Beck, M.J., V.F.), the Homburg Forschungsförderungsprogramm HOMFOR (A. Beck), and the Forschungskommission der Universität des Saarlandes (G.S., V.F., A. Beck). H.W. is a recipient of an Alexander von Humboldt research scholarship in the Flockerzi lab.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. Beck, M.A., and V.F.; Investigation, M.A., A. Beck, H.W., and A. Belkacemi; Resources, G.S., M.J., and V.F.; Project Administration, A. Beck and V.F.; Supervision, A. Beck, A. Bertl, G.S., and V.F.; Writing – Original Draft, A. Beck; Writing – Review and Editing, A. Beck, G.S., and V.F.; Funding Acquisition, A. Beck, G.S., M.J., and V.F.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 25, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Transparent Methods and six figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2018.11.037.

Supplemental Information

References

- Autzen H.E., Myasnikov A.G., Campbell M.G., Asarnow D., Julius D., Cheng Y. Structure of the human TRPM4 ion channel in a lipid nanodisc. Science. 2018;359:228–232. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batiza A.F., Schulz T., Masson P.H. Yeast respond to hypotonic shock with a calcium pulse. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:23357–23362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbey C., Weiss N., Legrand C., Allard B. Transient receptor potential canonical type 1 (TRPC1) operates as a sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak channel in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:36387–36394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.073221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertl A., Bihler H., Kettner C., Slayman C.L. Electrophysiology in the eukaryotic model cell Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Pflugers Arch. 1998;436:999–1013. doi: 10.1007/s004240050735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertl A., Bihler H., Reid J.D., Kettner C., Slayman C.L. Physiological characterization of the yeast plasma membrane outward rectifying K+ channel, DUK1 (TOK1), in situ. J. Membr. Biol. 1998;162:67–80. doi: 10.1007/s002329900343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertl A., Blumwald E., Coronado R., Eisenberg R., Findlay G., Gradmann D., Hille B., Kohler K., Kolb H.A., MacRobbie E. Electrical measurements on endomembranes. Science. 1992;258:873–874. doi: 10.1126/science.1439795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertl A., Gradmann D., Slayman C.L. Calcium- and voltage-dependent ion channels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1992;338:63–72. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1992.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertl A., Slayman C.L. Cation-selective channels in the vacuolar membrane of Saccharomyces: dependence on calcium, redox state, and voltage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1990;87:7824–7828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertl A., Slayman C.L. Complex modulation of cation channels in the tonoplast and plasma membrane of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: single-channel studies. J. Exp. Biol. 1992;172:271–287. doi: 10.1242/jeb.172.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair N.T., Kaczmarek J.S., Clapham D.E. Intracellular calcium strongly potentiates agonist-activated TRPC5 channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 2009;133:525–546. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodding M., Fecher-Trost C., Flockerzi V. Store-operated Ca2+ current and TRPV6 channels in lymph node prostate cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:50872–50879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillet L.E., Cardoso A.S., Perovano E., Pereira R.R., Ribeiro E.M., Tropia M.J., Fietto L.G., Tisi R., Martegani E., Castro I.M. The involvement of calcium carriers and of the vacuole in the glucose-induced calcium signaling and activation of the plasma membrane H(+)-ATPase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Cell Calcium. 2012;51:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantiello H.F., Montalbetti N., Goldmann W.H., Raychowdhury M.K., Gonzalez-Perrett S., Timpanaro G.A., Chasan B. Cation channel activity of mucolipin-1: the effect of calcium. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:304–312. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpaneto A., Cantu A.M., Gambale F. Redox agents regulate ion channel activity in vacuoles from higher plant cells. FEBS Lett. 1999;442:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Schlenstedt G., Flockerzi V., Beck A. Properties of the intracellular transient receptor potential (TRP) channel in yeast, Yvc1. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2028–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.C., Keller M., Hess M., Schiffmann R., Urban N., Wolfgardt A., Schaefer M., Bracher F., Biel M., Wahl-Schott C. A small molecule restores function to TRPML1 mutant isoforms responsible for mucolipidosis type IV. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4681. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Shen D., Samie M., Xu H. Mucolipins: intracellular TRPML1-3 channels. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2013–2021. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z., Paknejad N., Maksaev G., Sala-Rabanal M., Nichols C.G., Hite R.K., Yuan P. Cryo-EM and X-ray structures of TRPV4 reveal insight into ion permeation and gating mechanisms. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018;25:252–260. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis V., Cyert M.S. Internal Ca(2+) release in yeast is triggered by hypertonic shock and mediated by a TRP channel homologue. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:29–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerner J.F., Gisselmann G., Hatt H., Wetzel C.H. Transient receptor potential channel A1 is directly gated by calcium ions. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:13180–13189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X.P., Cheng X., Mills E., Delling M., Wang F., Kurz T., Xu H. The type IV mucolipidosis-associated protein TRPML1 is an endolysosomal iron release channel. Nature. 2008;455:992–996. doi: 10.1038/nature07311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J., Xie J., Yue L. Intracellular calcium activates TRPM2 and its alternative spliced isoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:7239–7244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811725106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn T., Gable K., Beeler T. Regulation of cellular Ca2+ by yeast vacuoles. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:7273–7278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Martinez C., Morenilla-Palao C., Planells-Cases R., Merino J.M., Ferrer-Montiel A. Identification of an aspartic residue in the P-loop of the vanilloid receptor that modulates pore properties. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:32552–32558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S.A., Guzman G.A., Wissenbach U., Philipp S.E., Zhu M.X., Bruns D., Cavalie A. TRPC5 is a Ca2+-activated channel functionally coupled to Ca2+-selective ion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:34423–34432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halachmi D., Eilam Y. Cytosolic and vacuolar Ca2+ concentrations in yeast cells measured with the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescence dye indo-1. FEBS Lett. 1989;256:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81717-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto S., Mori Y., Yabe I., Uozumi N. In vitro and in vivo characterization of modulation of the vacuolar cation channel TRPY1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS J. 2018;285:1146–1161. doi: 10.1111/febs.14399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara M., Takano Y., Yamashita A. General flexible nature of the cytosolic regions of fungal transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, revealed by expression screening using GFP-fusion techniques. Protein Sci. 2014;23:923–931. doi: 10.1002/pro.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida H., Yagawa Y., Anraku Y. Essential role for induced Ca2+ influx followed by [Ca2+]i rise in maintaining viability of yeast cells late in the mating pheromone response pathway. A study of [Ca2+]i in single Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells with imaging of fura-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:13391–13399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John Haynes W., Zhou X.L., Su Z.W., Loukin S.H., Saimi Y., Kung C. Indole and other aromatic compounds activate the yeast TRPY1 channel. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1514–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordt S.E., Tominaga M., Julius D. Acid potentiation of the capsaicin receptor determined by a key extracellular site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2000;97:8134–8139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100129497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange I., Yamamoto S., Partida-Sanchez S., Mori Y., Fleig A., Penner R. TRPM2 functions as a lysosomal Ca2+-release channel in beta cells. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra23. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launay P., Fleig A., Perraud A.L., Scharenberg A.M., Penner R., Kinet J.P. TRPM4 is a Ca2+-activated nonselective cation channel mediating cell membrane depolarization. Cell. 2002;109:397–407. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Zhang W.K., Benvin N.M., Zhou X., Su D., Li H., Wang S., Michailidis I.E., Tong L., Li X. Structural basis of dual Ca(2+)/pH regulation of the endolysosomal TRPML1 channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:205–213. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M., Cao E., Julius D., Cheng Y. Structure of the TRPV1 ion channel determined by electron cryo-microscopy. Nature. 2013;504:107–112. doi: 10.1038/nature12822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Mirabal H.R., Winther J.R. Redox characteristics of the eukaryotic cytosol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1783:629–640. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh D., Flemming R., Xu S.Z., Perraud A.L., Beech D.J. Critical intracellular Ca2+ dependence of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) cation channel activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11002–11006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oancea E., Vriens J., Brauchi S., Jun J., Splawski I., Clapham D.E. TRPM1 forms ion channels associated with melanin content in melanocytes. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra21. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olah M.E., Jackson M.F., Li H., Perez Y., Sun H.S., Kiyonaka S., Mori Y., Tymianski M., MacDonald J.F. Ca2+-dependent induction of TRPM2 currents in hippocampal neurons. J. Physiol. 2009;587:965–979. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.162289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C.P., Zhou X.L., Lin J., Loukin S.H., Kung C., Saimi Y. A TRP homolog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae forms an intracellular Ca(2+)-permeable channel in the yeast vacuolar membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:7801–7805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141036198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce D.A., Ferea T., Nosel S.A., Das B., Sherman F. Action of BTN1, the yeast orthologue of the gene mutated in Batten disease. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:55–58. doi: 10.1038/8861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prawitt D., Monteilh-Zoller M.K., Brixel L., Spangenberg C., Zabel B., Fleig A., Penner R. TRPM5 is a transient Ca2+-activated cation channel responding to rapid changes in [Ca2+]i. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:15166–15171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334624100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston R.A., Murphy R.F., Jones E.W. Assay of vacuolar pH in yeast and identification of acidification-defective mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1989;86:7027–7031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigamonti M., Groppi S., Belotti F., Ambrosini R., Filippi G., Martegani E., Tisi R. Hypotonic stress-induced calcium signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae involves TRP-like transporters on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Cell Calcium. 2015;57:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R.S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.K., Saotome K., Sobolevsky A.I. Swapping of transmembrane domains in the epithelial calcium channel TRPV6. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10669. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10993-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkus J., Beck A., Fleig A., Penner R. Regulation of TRPM2 by extra- and intracellular calcium. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;130:427–440. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z., Zhou X., Loukin S.H., Saimi Y., Kung C. Mechanical force and cytoplasmic Ca(2+) activate yeast TRPY1 in parallel. J. Membr. Biol. 2009;227:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s00232-009-9153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner H., Fleig A., Stokes A., Kinet J.P., Penner R. Discrimination of intracellular calcium store subcompartments using TRPV1 (transient receptor potential channel, vanilloid subfamily member 1) release channel activity. Biochem. J. 2003;371:341–350. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K., Montell C. TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:387–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T., Prenen J., Vriens J., Watanabe H., Janssens A., Wissenbach U., Bodding M., Droogmans G., Nilius B. Molecular determinants of permeation through the cation channel TRPV4. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:33704–33710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada Y., Ohsumi Y., Tanifuji M., Kasai M., Anraku Y. Vacuolar ion channel of the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:17260–17263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H., Vriens J., Janssens A., Wondergem R., Droogmans G., Nilius B. Modulation of TRPV4 gating by intra- and extracellular Ca2+ Cell Calcium. 2003;33:489–495. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissenbach U., Niemeyer B.A., Fixemer T., Schneidewind A., Trost C., Cavalie A., Reus K., Meese E., Bonkhoff H., Flockerzi V. Expression of CaT-like, a novel calcium-selective channel, correlates with the malignancy of prostate cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:19461–19468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R., Tang J., Wang C., Colton C.K., Tian J., Zhu M.X. Calcium plays a central role in the sensitization of TRPV3 channel to repetitive stimulations. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:6162–6174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706535200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Lee H.W., Yang W., Shealy S., Yang J.J. Probing site-specific calmodulin calcium and lanthanide affinity by grafting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3743–3750. doi: 10.1021/ja042786x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.L., Batiza A.F., Loukin S.H., Palmer C.P., Kung C., Saimi Y. The transient receptor potential channel on the yeast vacuole is mechanosensitive. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:7105–7110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230540100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.L., Su Z., Anishkin A., Haynes W.J., Friske E.M., Loukin S.H., Kung C., Saimi Y. Yeast screens show aromatic residues at the end of the sixth helix anchor transient receptor potential channel gate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:15555–15559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704039104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurborg S., Yurgionas B., Jira J.A., Caspani O., Heppenstall P.A. Direct activation of the ion channel TRPA1 by Ca2+ Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:277–279. doi: 10.1038/nn1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.