Abstract

Background:

It is still uncertain how surgical reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is able to restore rotatory laxity of the involved joint. The desired amount of restraint applied by the ACL graft, as compared with the healthy knee, has not been fully clarified.

Purpose:

To quantify the ability of single-bundle anatomic ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons in reducing the pivot-shift phenomenon immediately after surgery under anesthesia.

Study Design:

Case series; Level of evidence, 4.

Methods:

An inertial sensor and image analysis were used at 4 international centers to measure tibial acceleration and lateral compartment translation of the knee, respectively. The standardized pivot-shift test was quantified in terms of the side-to-side difference in laxity both preoperatively and postoperatively with the patient under anesthesia. The reduction in both tibial acceleration and lateral compartment translation after surgery and the side-to-side difference were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Alpha was set at P < .05.

Results:

A total of 107 patients were recruited for the study, and data were available for 89 patients. There was a statistically significant reduction in quantitative rotatory knee laxity between preoperatively (inertial sensor, 2.55 ± 4.00 m/s2; image analysis, 2.04 ± 2.02 mm) and postoperatively (inertial sensor, –0.54 ± 1.25 m/s2; image analysis, –0.10 ± 1.04 mm) between the involved and healthy joints, as measured by the 2 devices (P < .001 for both). Postoperatively, both devices detected a lower rotatory laxity value in the involved joint compared with the healthy joint (inertial sensor, 2.45 ± 0.89 vs 2.99 ± 1.10 m/s2, respectively [P < .001]; image analysis, 0.99 ± 0.83 vs 1.09 ± 0.92 mm, respectively [P = .38]).

Conclusion:

The data from this study indicated a significant reduction in the pivot shift when compared side to side. Both the inertial sensor and image analysis used for the quantitative assessment of the pivot-shift test could successfully detect restoration of the pivot shift after anatomic single-bundle ACL reconstruction. Future research will examine how pivot-shift control is maintained over time and correlation of the pivot shift with return to full activity in patients with an ACL injury.

Keywords: pivot shift, quantitative measurement of rotatory knee laxity, inertial sensors, image-based technique, ACL

A rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) significantly alters the kinematics and laxity of the knee joint.7,8,23 It is uncertain how ACL reconstruction, the standard medical intervention for active people, is able to restore the kinematics of the involved joint.7,43 The literature has demonstrated that the pivot-shift test, used for assessing rotatory and dynamic knee laxity, is associated with ACL deficiency and constitutes the most specific clinical tool for the examination of ACL ruptures.41 Moreover, the pivot-shift test correlates to subjective instability,24 reduced sport activity,22 and articular and meniscal damage.39 It should also be highlighted that full recovery of postoperative laxity is not always achieved when compared with the preinjury level of laxity.25,27

The pivot-shift phenomenon corresponds to tibial anterior translation, followed by a subsequent reduction of the lateral tibial compartment of the knee, replicating a symptom of dynamic laxity of the joint,33 and it reproduces the complex kinematics of the knee joint during multiplanar motion. Unfortunately, the main problem in using the pivot-shift test is the complexity of its quantification and its dependence on the specific surgeon’s sensitivity and experience.25,36,38

Innovative devices for the quantitative assessment of the pivot-shift test have been presented in the scientific literature, the most important being surgical navigation systems,26,31 image analysis systems,18,35 and inertial5,34,45,46 and electromagnetic sensors.37,38

In particular, using a navigation system has created the opportunity to quantify the significant postoperative reduction of the pivot-shift phenomenon after different surgical approaches,4,19,48 and it has also been used to show the nonsignificant influence of the degree of preoperative laxity on outcomes after reconstruction.28 Unfortunately, when using a navigation system, prior studies did not evaluate laxity outcomes in the healthy joint, as the insertion of intraosseous pins would be too invasive for a comparison. Even during in vitro studies in which a comparison with the native condition was possible, contrasting results were found comparing different surgical approaches to the preinjury condition.2 The quantitative evaluation of the pivot-shift test has been successfully conducted clinically using both a triaxial accelerometer and an electromagnetic system before surgery and at follow-up.3,9,38 However, the functional behavior of the ACL graft at the time of reconstruction is not well understood, and the desired amount of restraint applied by the ACL graft and as compared with the healthy knee has not been fully clarified.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine if anatomic single-bundle ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons would be able to restore rotatory knee laxity as measured by comparing postoperative laxity of the involved joint to the healthy knee joint. To accomplish this, an international multicenter prospective cohort study was conducted. It was hypothesized that a lower postoperative value of rotatory knee laxity would be detected after anatomic single-bundle ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons on the injured knee compared with the healthy knee.

Methods

This study was based on a multicenter prospective cohort study, the Prospective International Validation of Outcome Technology (PIVOT) trial, and involved 4 clinical centers, which all applied the same study protocol. Patients aged between 14 and 50 years who presented with a primary ACL injury and underwent surgery between December 2012 and February 2015 were considered eligible. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria for study eligibility are summarized in Table 1. Institutional review board approval was obtained from all 4 international centers before commencing the study. All the recruited patients provided written consent to participate.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteriaa

| Inclusion Criteria |

|

|

|

|

| Exclusion Criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

aACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

According to patient enrollment data, published elsewhere with preliminary data,44 a total of 107 patients with an ACL tear who underwent primary single-bundle ACL reconstruction were included in the PIVOT trial and were considered eligible for the present study. During data analysis, 18 patients were excluded because of incomplete laxity measurements. The remaining 89 patients (40 female and 49 male) were available for the study (Table 2). Concerning concomitant meniscal lesions, a displaced bucket-handle/longitudinal tear was found in 45 patients, a complex/horizontal lesion in 11 patients, and a radial/flap lesion in 15 patients (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Demographics of Patients (N = 89)a

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 23.4 ± 9.2 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 49 (55.1) |

| ACL injury pattern, n (%) | |

| Partial or mixed tear | 14 (15.7) |

| Complete tear in both bundles | 75 (84.3) |

aMixed tear refers to a partial tear in one ACL bundle and a complete tear in the other ACL bundle. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

TABLE 3.

Meniscal Lesions and Corresponding Surgical Treatmenta

| Medial Meniscus | Lateral Meniscus | |

|---|---|---|

| Lesion present | 36 (40.4) | 35 (39.3) |

| Tear type | ||

| Displaced bucket handle/longitudinal | 23 (25.8) | 22 (24.7) |

| Complex/horizontal | 7 (7.9) | 4 (4.4) |

| Radial/flap | 6 (6.7) | 9 (10.1) |

| Treatment strategy | ||

| No meniscus surgery | 2 (2.2) | 10 (11.2) |

| Meniscectomy | 10 (11.2) | 10 (11.2) |

| Meniscus repair with 1-2 sutures | 17 (19.1) | 14 (15.7) |

| Meniscus repair with ≥3 sutures | 7 (7.9) | 1 (1.1) |

aData are reported as n (%).

Surgical Technique

All patients underwent anatomic single-bundle ACL reconstruction performed with autologous hamstring tendons. To synchronize the same surgical technique for all the 4 sites involved in the multicenter study, a member of the PIVOT trial visited each site and reviewed critical steps of the technique. An oblique skin incision was made above the pes anserinus, and both semitendinosus and gracilis autografts were harvested and looped on a suture button device in a quadrupled fashion.42 After diagnostic arthroscopic surgery and the treatment of eventual meniscal lesions, the ACL footprints were identified, and tibial and femoral tunnels were created in the central position after identifying the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles according to anatomic landmarks.2 Specifically, the femoral ACL insertion was prepared, and the center of the anatomic footprint was identified with arthroscopic references. The center of the anatomic position was marked with a microfracture awl posteriorly to the lateral intercondylar ridge and in the center between the anteromedial and posterolateral bundles. The femoral tunnel was created through the anteromedial portal. The tunnels were reamed according to the size of the graft, which was fixed with a suture button in the femoral side and an interference screw in the tibial side at 20° of flexion.

No fluoroscopy or postoperative computed tomography was used to check tunnel placement to avoid patients’ exposure to radiation. All surgical procedures in the 4 centers were performed by senior surgeons, who were all trained in sports medicine with more than 10 years of experience in ACL reconstruction and were familiar with both single-bundle and double-bundle techniques.

Pivot-Shift Test

At all 4 sites, the pivot-shift test was performed preoperatively in the operating room with the patient under general anesthesia. The pivot-shift test was then repeated with nonsterile devices immediately after ACL reconstruction, after skin closure and wound medication, with the patient still in the operating room and under anesthesia to reproduce the preoperative condition. During both occasions, the pivot-shift test was performed by an expert orthopaedic surgeon, on the involved joint as well as the healthy joint, to define the side-to-side difference in laxity. The side-to-side difference was calculated by subtracting the value of laxity acquired on the healthy joint from the one acquired on the involved joint for each patient.

The pivot-shift test was performed as reported in the literature by Galway and MacIntosh12 in 1980 and Jakob et al21 in 1987. To optimize standardization of the maneuver, an instructional video reproducing pivot shift was shown to all the surgeons involved in the study before starting with the measurements.16

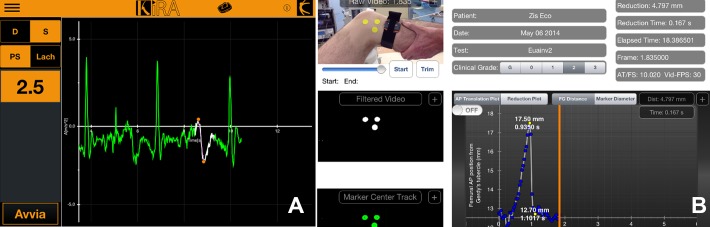

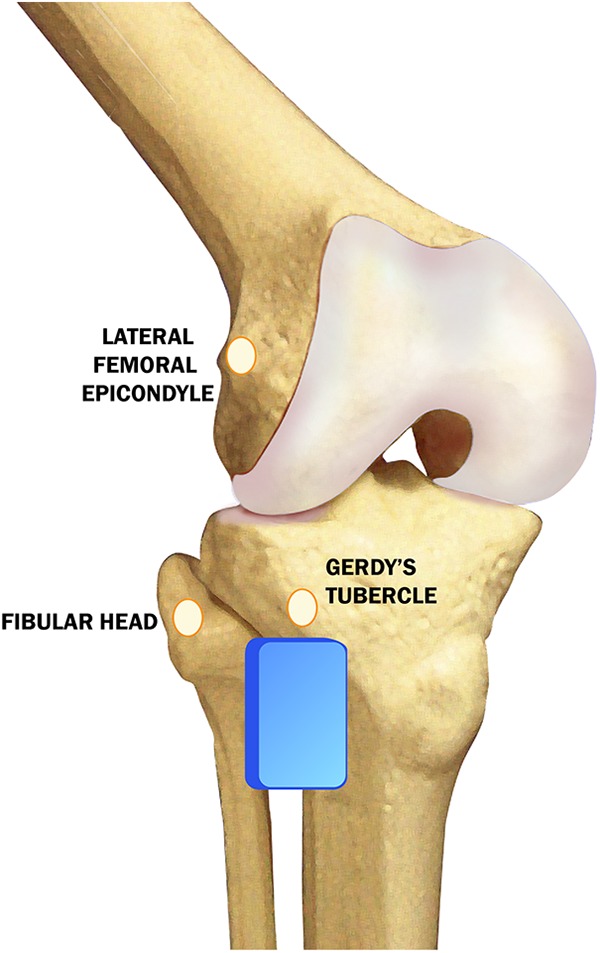

A quantitative assessment of tibial acceleration and lateral compartment translation relative to the femur during the pivot-shift test was performed using an inertial sensor and image analysis. The first device, called the KiRA (I+),45,46 uses inertial sensors to analyze tibial acceleration of the tibial reduction that occurs during the pivot-shift test. The device works with a sampling rate of 120 Hz. A specifically developed application was installed on an iPad (Apple) to analyze and plot the signal and to monitor and quantify the clinical test (Figure 1A). To reach optimal stability and data acquisition, it was necessary to fix the sensor on the skin surface in the proximity of the Gerdy tubercle (Figure 2) by a specific hypoallergenic strap.

Figure 1.

Software interface for (A) the KiRA device and (B) the image-based device. The graphs represent the trend of tibial acceleration and lateral compartment translation during the pivot-shift test, respectively.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the position of the KiRA device (blue box) and markers (yellows circles) required for image analysis.

A second device, an image-based system, has been simultaneously used to quantify the pivot-shift phenomenon.17,18 It uses a digital camera and a specifically developed application installed on an iPad that automatically processes the acquired signal to determine lateral compartment translation (Figure 1B). The device required the application of yellow skin markers, 1.9 cm in diameter (Color Coding Labels; Avery Dennison), which were applied in 3 positions: on the fibular head, on the lateral epicondyle, and on the Gerdy tubercle (Figure 2). The 2 devices were developed independently from one another.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for each quantitative measurement obtained during the assessment of dynamic rotatory knee laxity. Laxity data are presented as mean ± SD. The side-to-side difference was calculated by subtracting the value of laxity on the healthy joint from the value acquired on the involved joint. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparisons between preoperative and postoperative conditions and laxity differences by sex. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to assess the strength of the association that existed between age and the side-to-side difference in laxity.

Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were completed with SPSS Statistics Software version 23 (IBM).

Results

The side-to-side difference measured in the operating room just after ACL reconstruction was significantly reduced compared with the preoperative side-to-side difference in terms of dynamic rotatory laxity during the pivot-shift test for both the KiRA (P < .001) and the image-based system (P < .001) (Table 4). There was decreased rotatory laxity in the involved joint postoperatively, as measured by the 2 devices, when compared with the healthy side. This is demonstrated by the negative values of the side-to-side difference in the postoperative condition.

TABLE 4.

Preoperative Versus Postoperative Side-to-Side Difference in Laxity

| KiRA, m/s2 | Image Analysis, mm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P | Mean ± SD | P | |

| Preoperative | 2.55 ± 4.00 | <.001 | 2.04 ± 2.02 | <.001 |

| Postoperative (immediately after reconstruction) | –0.54 ± 1.25 | –0.10 ± 1.04 | ||

A comparison between the postoperative involved joint and healthy joint was also performed. Both devices detected a lower rotatory laxity value during the pivot-shift test in terms of tibial acceleration and lateral compartment translation of the involved joint when compared with the healthy knee (Table 5). For measurements performed with the KiRA, the comparison between the healthy and involved knees resulted in a statistically significant difference (P < .001), while image analysis demonstrated a nonsignificant difference.

TABLE 5.

Contralateral Versus Postoperative Involved Knee Laxity

| KiRA, m/s2 | Image Analysis, mm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P | Mean ± SD | P | |

| Healthy knee | 2.99 ± 1.10 | <.001 | 1.09 ± 0.92 | .38 |

| Involved knee immediately after reconstruction | 2.45 ± 0.89 | 0.99 ± 0.83 | ||

Moreover, when measured with the KiRA device, preoperative laxity of female patients was significantly higher (P = .0021) than that of male patients, whereas no statistical differences were found for postoperative laxity as well as for image-based system measurements both before and after ACL reconstruction (Table 6). No significant association was found between age and the side-to-side difference in laxity either before or after ACL reconstruction using the KiRA and image analysis.

TABLE 6.

Side-to-Side Difference in Laxity Between Female and Male Athletesa

| Female (n = 40) | Male (n = 49) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | |||

| KiRA, m/s2 | 3.71 ± 5.26 | 1.61 ± 2.20 | .0021 |

| Image analysis, mm | 1.82 ± 1.47 | 2.23 ± 2.38 | .9088 |

| Postoperative (immediately after reconstruction) | |||

| KiRA, m/s2 | –0.61 ± 1.05 | –0.48 ± 1.40 | .7113 |

| Image analysis, mm | –0.18 ± 1.09 | –0.03 ± 1.01 | .2310 |

aData are reported as mean ± SD.

Discussion

The main finding of this prospective multicenter cohort study was that dynamic rotatory knee laxity after single-bundle anatomic ACL reconstruction was efficiently reduced, with a lower value for both lateral compartment translation and tibial acceleration compared with the healthy joint. A significant reduction in the side-to-side difference in laxity between preoperative to postoperative measurements was detected by the 2 devices used for the quantitative assessment of the pivot-shift test. The clinical benefit of the quantification of the pivot-shift test is substantial, as it enables clinicians to have quantitative information concerning the reduction in postoperative dynamic laxity directly after surgery so as to optimize and personalize treatment after ACL surgery.

The study findings are in line with previous in vivo scientific work that has shown a reduction in laxity after ACL reconstruction by an examination of the pivot-shift test.28,47 Unfortunately, as these studies used a navigation system, it was not possible to quantify the side-to-side difference in laxity.

In the present study, the values for lateral compartment translation evaluated with image analysis on the involved joint immediately after surgery were not significantly different from the data acquired on the healthy joint, although when considering measurements with the KiRA device, the laxity values between the involved and healthy sides were significantly different (P < .001) and demonstrated a lower value of acceleration for the involved joint postoperatively. The fact that the various testing methods produced different results could be explained by 2 potential factors. First, there was a difference in the standard deviation of the acquired data that was greater for the image-based device compared with the KiRA. Second, a potential difference in kinematic sensitivity could affect the results. Third, acceleration and lateral tibial displacement of the tibial reduction during the pivot-shift test are 2 separate aspects of the pivot-shift phenomenon, and their correlation needs to be assessed.

Nevertheless, this apparent difference between the 2 joints detected by the KiRA device immediately after surgery was lower than the difference found in a previous study3 comparing the ACL-deficient joint with the healthy joint (side-to-side difference: 0.8 ± 0.3 m/s2; P < .01). The amount of rotatory overconstraint able to affect clinical outcomes of ACL reconstruction is still under discussion; therefore, the clinical relevance of such differences could be questioned.

Moreover, it is known that over time the graft loosens and that residual laxity plays an important role in remodeling the graft itself and might be responsible for premature loosening and failure of the performed reconstruction procedure.35 The evolution of knee stability over time is still a concern. Previous studies focusing on anterior-posterior laxity found a clinically important increase in sagittal plane of the involved joint during the first 2 years after surgery with both a bone–patellar tendon–bone allograft and autograft10 and cryopreserved tibialis anterior allografts40 in 9% to 22% of the knees.

Also, the viscoelastic properties of soft tissue tendon grafts used for ACL reconstruction have been reported in the scientific literature as critical variables for postoperative outcomes and the potential for graft elongation, thus resulting in decreased graft tension and higher laxity after surgery over time.11,20 From this perspective, it could be considered a positive aspect to have the graft slightly overconstrained. Clinically, rotational overconstraint may raise the concern of abnormal joint contact and kinematics, potentially leading to premature osteoarthritis onset and decreased physiological motion. The detected lower value of laxity for the involved knee could also be related to the required prudence in postoperative measurements. It would need to be re-evaluated at midterm or long-term follow-up, and its clinical relevance has to be investigated.

Lower postoperative values of laxity in the involved knee joint compared with the healthy knee are in contrast with previous studies that used the same KiRA device.3,15 These studies did not find any significant difference between the involved and healthy knee joints at time zero15 and at 6 months after surgery.3 Both studies confirmed the reduction of the pivot-shift phenomenon after ACL reconstruction. However, future research may better elucidate the persistence of such a laxity difference and its clinical relevance at a longer time of follow-up after anatomic single-bundle reconstruction using hamstring tendons, when the graft used for reconstruction is well integrated into the joint.

As an example, differences between operated and healthy knees were confirmed in a recent study6 that analyzed 18 patients at 9 years of follow-up after ACL reconstruction and lateral tenodesis using a robotic lower-leg axial rotation testing system. In contrast, patients who underwent only intra-articular ACL reconstruction demonstrated no significant differences between their legs. The findings of the present study seem to be in contrast with those of recent in vivo studies that have shown how single-bundle reconstruction was not able to fully restore normal rotatory stability during daily life motor activities in the operated knee compared with the healthy one.13,14 However, those studies had different follow-up periods, and the measurements were performed with different devices, thus emphasizing the importance of repeating the analysis at a longer follow-up.

Further confirmation of the validity of the 2 methods used in this study to quantify joint laxity was provided in a controlled laboratory study that showed how the pivot-shift test is reliably quantifiable by acceleration and/or tibial translation beyond its procedural variation.25 This is also in line with a systematic review30 that reported anterior-posterior translation, internal-external rotation, and acceleration as the main parameters for the quantification of the pivot-shift test. Both of the devices performed the measurements using fixed skin sensors. This could represent a possible source of errors connected with soft tissue artifacts. However, the 2 devices have been previously validated with clinical pivot-shift grades,36 in which both were able to detect differences between low- and high-grade pivot-shift test results. Moreover, the KiRA device has been validated with a navigation system,29 while the image-based device has been validated with an electromagnetic tracking system,1 with a good positive correlation in both of the studies. Additionally, standardization of the pivot-shift test has been proven to provide a more consistent quantitative evaluation, especially useful when designing multicenter studies.16

In the present work, we included patients with not only isolated ACL tears but also those with a combined meniscal lesion because this is a very common situation in cases of ACL injuries. A previous study32 found that ACL reconstruction with medial meniscal repair did not reveal significant differences in knee kinematics compared with the intact knee. Therefore, we believe that performing the meniscal repairs produced a minimal impact on the results. On the other hand, meniscal repair could have contributed to a reduction in rotatory laxity, and the effects of meniscal treatment on noninvasive kinematic evaluations should be therefore investigated in further studies.

The clinical relevance of this study is that single-bundle anatomic ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons was able to reduce dynamic laxity of the involved knee, with values comparable with those of the healthy side. Future studies will have to confirm if the results found at time zero after surgery will be valid even at a longer follow-up and to investigate the factors contributing to preoperative and postoperative laxity.

Conclusion

A significant reduction in the side-to-side difference in laxity between preoperative and postoperative measurements was detected by 2 devices used for the quantitative assessment of dynamic rotatory knee laxity. This finding implies that in patients with an ACL injury, single-bundle anatomic ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons can significantly reduce the pivot-shift phenomenon. Future research may better elucidate the persistence of the reduction in dynamic laxity at a longer time of follow-up after surgery.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: This work was supported by a grant from the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine and the Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation (grant No. 708661). S.Z. is a consultant for Smith & Nephew and DePuy. V.M. is a consultant for Smith & Nephew, has grants/grants pending from Mid-Atlantic Surgical, and receives educational support from Arthrex. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli.

References

- 1. Arilla FV, Rahnemai-Azar AA, Yacuzzi C, et al. Correlation between a 2D simple image analysis method and 3D bony motion during the pivot shift test. Knee. 2016;23:1059–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bedi A, Musahl V, O’Loughlin P, et al. A comparison of the effect of central anatomical single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on pivot-shift kinematics. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1788–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berruto M, Uboldi F, Gala L, Marelli B, Albisetti W. Is triaxial accelerometer reliable in the evaluation and grading of knee pivot-shift phenomenon? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:981–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bignozzi S, Zaffagnini S, Lopomo N, Fu FH, Irrgang JJ, Marcacci M. Clinical relevance of static and dynamic tests after anatomical double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borgstrom PH, Markolf KL, Wang Y, et al. Use of inertial sensors to predict pivot-shift grade and diagnose an ACL injury during preoperative testing. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:857–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Branch T, Lavoie F, Guier C, et al. Single-bundle ACL reconstruction with and without extra-articular reconstruction: evaluation with robotic lower leg rotation testing and patient satisfaction scores. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:2882–2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brandsson S, Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Kärrholm J. Kinematics after tear in the anterior cruciate ligament: dynamic bilateral radiostereometric studies in 11 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bulgheroni P, Bulgheroni MV, Andrini L, Guffanti P, Giughello A. Gait patterns after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bull AMJ, Earnshaw PH, Smith A, Katchburian MV, Hassan ANA, Amis AA. Intraoperative measurement of knee kinematics in reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:1075–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chang SKY, Egami DK, Shaieb MD, Kan DM, Richardson AB. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: allograft versus autograft. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feller JA, Webster KE. A randomized comparison of patellar tendon and hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:564–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Galway HR, MacIntosh DL. The lateral pivot shift: a symptom and sign of anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;(147):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Georgoulis AD, Papadonikolakis A, Papageorgiou CD, Mitsou A, Stergiou N. Three-dimensional tibiofemoral kinematics of the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient and reconstructed knee during walking. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Georgoulis AD, Ristanis S, Chouliaras V, Moraiti C, Stergiou N. Tibial rotation is not restored after ACL reconstruction with a hamstring graft. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;454:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hardy A, Casabianca L, Hardy E, Grimaud O, Meyer A. Combined reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament associated with anterolateral tenodesis effectively controls the acceleration of the tibia during the pivot shift. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoshino Y, Araujo P, Ahlden M, et al. Standardized pivot shift test improves measurement accuracy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:732–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoshino Y, Araujo P, Ahlden M, et al. Quantitative evaluation of the pivot shift by image analysis using the iPad. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:975–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoshino Y, Araujo P, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Musahl V. An image analysis method to quantify the lateral pivot shift test. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:703–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, Yamamoto Y, Tsukada H, Toh S. Navigation evaluation of the pivot-shift phenomenon during double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: is the posterolateral bundle more important? Arthroscopy. 2009;25:488–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jaglowski JR, Williams BT, Turnbull TL, LaPrade RF, Wijdicks CA. High-load preconditioning of soft tissue grafts: an in vitro biomechanical bovine tendon model. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jakob RP, Stäubli HU, Deland JT. Grading the pivot shift: objective tests with implications for treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:294–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaplan Y. Identifying individuals with an anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee as copers and noncopers: a narrative literature review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2011;41:758–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim K, Jeon K, Mullineaux DR, Cho E. A study of isokinetic strength and laxity with and without anterior cruciate ligament injury. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28:3272–3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kujala UM, Nelimarkka O, Koskinen SK. Relationship between the pivot shift and the configuration of the lateral tibial plateau. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1992;111:228–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuroda R, Hoshino Y, Kubo S, et al. Similarities and differences of diagnostic manual tests for anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency: a global survey and kinematics assessment. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lane CG, Warren RF, Stanford FC, Kendoff D, Pearle AD. In vivo analysis of the pivot shift phenomenon during computer navigated ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lie DTT, Bull AMJ, Amis AA. Persistence of the mini pivot shift after anatomically placed anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;457:203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lopomo N, Signorelli C, Bonanzinga T, et al. Can rotatory knee laxity be predicted in isolated anterior cruciate ligament surgery? Int Orthop. 2014;38:1167–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lopomo N, Signorelli C, Bonanzinga T, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Visani A, Zaffagnini S. Quantitative assessment of pivot-shift using inertial sensors. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lopomo N, Zaffagnini S, Amis AA. Quantifying the pivot shift test: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:767–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lopomo N, Zaffagnini S, Bignozzi S, Visani A, Marcacci M. Pivot-shift test: analysis and quantification of knee laxity parameters using a navigation system. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lorbach O, Kieb M, Domnick C, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of knee kinematics after anatomic single- and anatomic double-bundle ACL reconstructions with medial meniscal repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:2734–2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Losee RE. Concepts of the pivot shift. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;172:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maeyama A, Hoshino Y, Debandi A, et al. Evaluation of rotational instability in the anterior cruciate ligament deficient knee using triaxial accelerometer: a biomechanical model in porcine knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1233–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ménétrey J, Duthon VB, Laumonier T, Fritschy D. “Biological failure” of the anterior cruciate ligament graft. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Musahl V, Griffith C, Irrgang JJ, et al. Validation of quantitative measures of rotatory knee laxity. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2393–2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nagai K, Araki D, Matsushita T, et al. Biomechanical function of anterior cruciate ligament remnants: quantitative measurement with a 3-dimensional electromagnetic measurement system. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:1359–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nagai K, Hoshino Y, Nishizawa Y, et al. Quantitative comparison of the pivot shift test results before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction by using the three-dimensional electromagnetic measurement system. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:2876–2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Noyes FR, Matthews DS, Mooar PA, Grood ES. The symptomatic anterior cruciate-deficient knee, part II: the results of rehabilitation, activity modification, and counseling on functional disability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65:163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nyland J, Caborn DNM, Rothbauer J, Kocabey Y, Couch J. Two-year outcomes following ACL reconstruction with allograft tibialis anterior tendons: a retrospective study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prins M. The Lachman test is the most sensitive and the pivot shift the most specific test for the diagnosis of ACL rupture. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Prodromos C, Joyce B. Endobutton femoral fixation for hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: surgical technique and results. Tech Orthop. 2005;20:233–237. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sundemo D, Alentorn-Geli E, Hoshino Y, Musahl V, Karlsson J, Samuelsson K. Objective measures on knee instability: dynamic tests. A review of devices for assessment of dynamic knee laxity through utilization of the pivot shift test. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016;9(2):148–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Svantesson E, Hamrin Senorski E, Mårtensson J, et al. Static anteroposterior knee laxity tests are poorly correlated to quantitative pivot shift in the ACL-deficient knee: a prospective multicentre study. J ISAKOS. 2018;3:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zaffagnini S, Lopomo N, Signorelli C, et al. Inertial sensors to quantify the pivot shift test in the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Joints. 2014;2:124–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zaffagnini S, Lopomo N, Signorelli C, et al. Innovative technology for knee laxity evaluation: clinical applicability and reliability of inertial sensors for quantitative analysis of the pivot-shift test. Clin Sports Med. 2013;32:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zaffagnini S, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Signorelli C, et al. Anatomic and nonanatomic double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an in vivo kinematic analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:708–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zaffagnini S, Signorelli C, Lopomo N, et al. Anatomic double-bundle and over-the-top single-bundle with additional extra-articular tenodesis: an in vivo quantitative assessment of knee laxity in two different ACL reconstructions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20:153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]