Abstract

Background: We previously reported that modulation of cytokeratin18 induces pleomorphism of liver cells, higher cell motility, and higher drug sensitivity to sorafenib treatment of hepatoma cells. These relationships were established by in vitro experiments. The aim of this study was to determine the in vivo association between cytokeratin expression and tumor behavior, as well as cancer stem cells of hepatocellular carcinoma and intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma in Taiwan.

Methods: Cytokeratins and sal-like protein 4 expression was determined in 83 hepatocellular carcinoma and 30 intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma specimens by immunohistochemistry. The relationship between cytokeratins and sal-like protein 4 expression with hepatitis virus infection, clinicopathologic factors, and survival was analyzed. Further, the correlation among cytokeratins and sal-like protein 4 expression was studied.

Results: In addition to cytokeratin8/18, the expression of cytokeratin7/19 and sal-like protein 4 was noted in hepatocellular carcinoma; however, only cytokeratin19 expression had a significant correlation with poor overall survival and poor disease-free survival. The expression of cytokeratins and sal-like protein 4 was not correlated with hepatitis virus infection. The expression of cytokeratin19, but not 7, 8, and 18, was correlated with sal-like protein 4 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cytokeratin7 expression was decreased and the sal-like protein 4 expression was absent in all 30 intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma cases. The expression of cytokeratins had not statistically significant correlation with overall and disease-free survival in patients with intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Conclusions: The expression of cytokeratin19 was associated with sal-like protein 4 expression, as well as poor overall and disease-free survival in hepatocellular carcinoma patients in Taiwan.

Keywords: cholangiocarcinoma, cytokeratin, hepatocellular carcinoma, sal-like protein 4

Introduction

Primary liver cancer (PLC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Taiwan and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide 1. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), thought to originate from hepatocytes and cholangiocytes, respectively, are the two major forms of PLC and accounting for 85%-90% and 5%-10% of cases, respectively 2. Cytokeratin (CK) is a cytoskeletal intermediate filament. Different epithelial cells express characteristic combinations of CK polypeptides. In normal human liver, hepatocytes typically express CK8 and CK18, while bile duct cells predominantly express CK7 and CK19, as well as CK8 and CK18 3, 4.

Human HCC and ICC cells are morphologically different from hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. We have identified the pleomorphism of these cancer cells is caused by instability and disorganization of the cytoskeleton system. An unstable cytoskeleton may also play a role in tumor biology, including tumor transformation, tumor progression, local invasion, and distant metastasis. In our previous study, modulation of CK18 in human HCC was established 5, 6, and we showed that plectin, a versatile cytoskeleton cross-linking protein in a variety of tissues and cells, was deficient in human HCC 7. We recently reported that by affecting the expression and organization of CK18, a plectin deficiency partially augments the cytoskeleton and induces pleomorphic changes in liver cells 8, 9. In addition, plectin-deficient human liver cells exhibit higher cell motility and are associated with an increase in focal adhesion kinase activity that is comparable to the properties of invasive HCC 10. Moreover, we have shown that plectin deficiency and increased E-cadherin in hepatoma cells are associated with higher rates of cell motility, collective cell migration, as well as higher drug sensitivity to sorafenib treatment 11.

High recurrent rates of HCC impact the curative effect after hepatectomy. Many risk factors, including tumor size, tumor focality, histologic grade, and vascular invasion, have been shown to be closely associated with the recurrence and survival of HCC patients 12, 13. At the molecular level, the relationship between the expression of cancer stem cell (CSC) markers, such as CD133, CD90, CD44, EpCAM, CK19, and sal-like protein 4 (SALL4), and poorer outcomes in patients with HCC has been established 14-19. SALL4 is an oncofetal protein that is expressed in the human fetal liver and silenced in the adult liver, but SALL4 is re-expressed in a subgroup of patients who have HCC and an unfavorable prognosis 19. Recently, several CSC prognostic markers or therapeutic targets have been reported in human ICC 20, 21; however, very little information exists with respect to SALL4 in ICC.

The relationship between tumor transformation and CK18 modulation in HCC was established in our previous study using an in vitro experiment model 7, 9. The aim of this study was to determine the association between CK expression and tumor behavior in HCC patients of Taiwan. Using immunohistochemistry, the expression of CK8/18 and CK7/19 was examined and the results will be correlated with clinical data of HCC. Because CSCs have been proposed to be cancer-initiating cells, the expression of CKs will be correlated with the CSC marker, SALL4, in this study to understand the development of HCC. In addition, reports about the CKs and SALL4 in ICC are limited. We therefore determined whether or not the phenomenon in HCC is equivalent in ICC. We hope our study will provide a critical assessment about the development of human HCC and ICC in Taiwan.

Materials and Methods

Patients and tissue specimens

Unstained formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections of totally 113 patients, including 30 cases of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-associated HCC, 27 cases of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated HCC, 26 cases of viral infection-free (NBNC) HCC, and 30 cases of ICC, were included in this study. The specimens were obtained from the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) Biobank (TLCN No. 150099). The medical records were reviewed and characteristic, pathologic, and clinical data were extracted. This retrospective histological correlation study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Show Chwan Memorial Hospital (No. 1041105).

Immunohistochemistry

Using the Bond-Max autostainer (Leica Biosystems, 099253 Singapore), tissue sections were stained with CK7, CK19, CK8, CK18, and SALL4 monoclonal antibodies. The details of these immunomarkers are provided in Table 1. Slides stained with the previously mentioned antibodies were performed on the fully automated Bond-Max system using onboard heat-induced antigen retrieval and a Leica Refine Polymer Detection System (Leica Biosystems). Diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogen (Leica Biosystems) in all immunostains. Positive control used in each immunostain reaction: human breast tissue for CK7, human pancreatic ducts for CK19, human liver tissue for CK8 and 18, human seminoma tissue for SALL4. Negative control is to perform the immunostain with the primary antibody omitted and substitution of preimmune serum at the same protein concentration as the primary antibody. The images were captured by the Olympus BX51 microscopic/ DP71 Digital Camera System (Ina-shi, Nagano, Japan) for study comparison.

Table 1.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antigen | Clone | Product code | Antibody class | Supplier | Dilution | Antigen retrieval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK7 | Mouse monoclonal | NCL-CK7-OVTL | IgG1 | Leica | 1:200 | ER2 20 min |

| CK19 | Mouse monoclonal | BA17 | IgG1 | ZETA | 1:100 | ER2 20 min |

| CK8 | Mouse monoclonal | TA500021 | IgG2b | OriGene | 1:200 | ER2 20 min |

| CK18 | Mouse monoclonal | TA500015 | IgG1 | OriGene | 1:200 | ER2 20 min |

| SALL4 | Rabbit monoclonal | EP299 | IgG | ZETA | 1:200 | ER2 20 min |

ER1: Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 1 contains a citrate-based buffer and surfactant. ER2: Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 contains an ethylene diaminetetra-acetic acid-based buffer and surfactant.

Interpretation of CKs and SALL4 expression

The immunohistochemical staining slides were interpreted by two pathologists who were blinded to the clinical data. The interpretation was based on a semi-quantitative system; the staining intensity and proportion. At least 1000 cells in 5 randomly chosen areas of the tumor tissues were analyzed in each section at ×400 magnifications. The staining intensity was scored as 0 (negative), 1 (weak), 2 (intermediate), or 3 (strong). The staining proportion was scored as 0 (negative), 1 (1%-10%), 2 (11%-50%), or 3 (51%-100%) according to the percentage of immunoreactive tumor cells. The final score (immunoreactive score [IRS]) was calculated by multiplying the intensity score by the proportion score.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 24.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the interval falling between the date of surgery and the date of tumor recurrence or the date of the most recent follow-up with no proof of tumor recurrence. At the time of the previous visit for regular follow-up, a censor was performed on overall survival (OS) time. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the probabilities of OS and DFS, and the log-rank test was used to detect differences between the curves. A chi-square test and Student's t-test were used to analyze the clinical data, as indicated. A difference of P-value < 0.05 between groups was considered statistically significant. Spearman's correlation analysis was used to analyze the relationships among the expression of CK7/19, CK8/18, and SALL4.

Results

Expression of CKs and SALL4 in HCC tissues

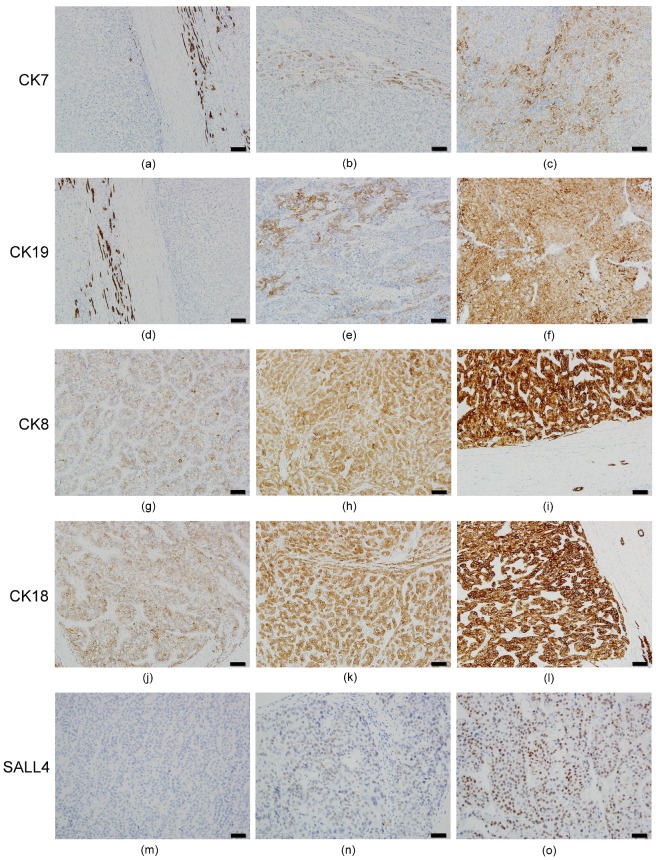

The results of HCC immunostaining are shown in Figure 1. Twenty-seven of 83 HCCs (32.5%) were positive for CK7 expression (Figures 1b and 1c), while 18 (21.7%) were positive for CK19 (Figures 1e and 1f). The results conflicted traditional dogma because CK7/19 was recognized as no expression in hepatocytes and HCC. Overexpression of CK7/19 in HCC was identified in this study; however, we noticed that there is no IRS=9 expression pattern for CK7/19 in HCC.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical expression pattern of CKs and SALL4 in HCC. All of the HCC cases had a negative (IRS=0) or decreased (IRS 1~4) expression pattern for CK7. (a) Negative expression in HCC portion (left side) and normal expression (IRS=9) in bile ducts (right side) for CK7. (b) IRS=2 expression pattern for CK7. (c) IRS=4 expression pattern for CK7. (d) Negative expression in HCC portion (right side) and normal expression in bile ducts (left side) for CK19. (e) IRS=4 expression pattern for CK19. (f) IRS=6 expression pattern for CK19. There is no IRS=9 expression pattern for CK19 in HCC. For CK8, IRS=3 (g), IRS=6 (h), and IRS=9 (i) are noted. For CK18, IRS=3 (j), IRS=6 (k), and IRS=9 (l) are noted. All of the HCC cases had positive expression (IRS 1~9) for CK8 and CK18, and no negative expression was found. For SALL4, negative (m), punctate (n), and diffuse intense (o) expression pattern are noted. Bar =100 um (100X) in figures a~l, bar =50 um (200X) in figures m~o.

All HCC specimens were CK8/18-positive; however, the extent of expression was uneven. Sixty (72.3%) and 49 (59.0%) cases had decreased expression (IRS 1~6) of CK8 (Figures 1g and 1h) and CK18 (Figures 1j and 1k), respectively. The normal expression pattern (IRS=9) of CK8 (Figure 1i) and CK18 (Figure 1l) was only 27.7% and 41.0%, respectively. The results were in agreement with our previous data 5-7, suggesting that CK18 is modulated and down expression in HCC.

For the SALL4 expression, only 20 cases (24.1%) were SALL4-positive (punctate [Figure 1n] or diffuse intense [Figure 1o]) in HCC, while non-tumor hepatocytes revealed no SALL4 expression.

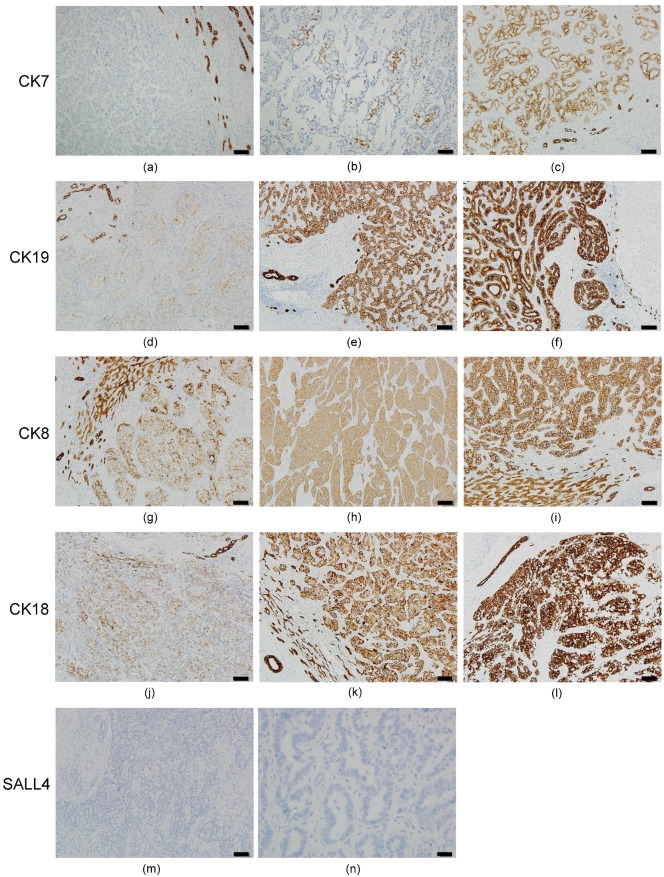

Expression of CKs and SALL4 in ICC tissues

The results of ICC immunostaining are shown in Figure 2. Of the 30 ICC cases, 100% had decreased CK7 expression (IRS 0~6) in the tumor portion (Figures 2a-2c). Six cases (20%) had negative CK7 expression (IRS=0) (Figure 2a). The expression rate of CK19, CK8, and CK18 were 100% in ICC, but the extent of expression was not uniform. Decreased expression (IRS 1~6) for CK19 (Figures 2d and 2e), CK8 (Figures 2g and 2h), and CK18 (Figures 2j and 2k) was 83.3% (25 cases), 30% (9 cases), and 23.3% (7 cases), respectively. Other cases had normal CK19 (Figure 2f), CK8 (Figure 2i) and CK18 (Figure 2l) expression (IRS=9). We also found that bile duct epithelium was diffusely strong positive (IRS=9) in all of the 30 ICC cases for CK7/19 and CK8/18. Surprisingly, all of the 30 ICC cases had negative staining for SALL4 in the tumor portion and bile duct epithelium (Figures 2m and 2n).

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical expression pattern of CKs and SALL4 in ICC. All of the ICC cases had a negative (IRS=0) or decreased (IRS 1~6) expression for CK7. (a) Negative expression in the ICC portion (left side) and normal expression (IRS=9) in the bile ducts (right side) for CK7. (b) IRS=2 expression pattern for CK7. (c) IRS=6 expression pattern in the ICC portion and normal expression in the bile duct for CK7. IRS=3 expression pattern presented in ICC for CK19 (d), CK8 (g) and CK18 (j). IRS=6 expression pattern presented in ICC for CK19 (e), CK8 (h), and CK18 (k). IRS=9 expression pattern presented in ICC for CK19 (f), CK8 (i), and CK18 (l). Negative expression was not found for CK19, CK8, and CK18 in ICC. All of the ICC cases reveal negative expression for SALL4 (m and n). Bile duct epithelium also presented negative expression for SALL4 (m, upper left portion). Bar =100 um (100X) in figures a~m, bar =20 um (400X) in figure n.

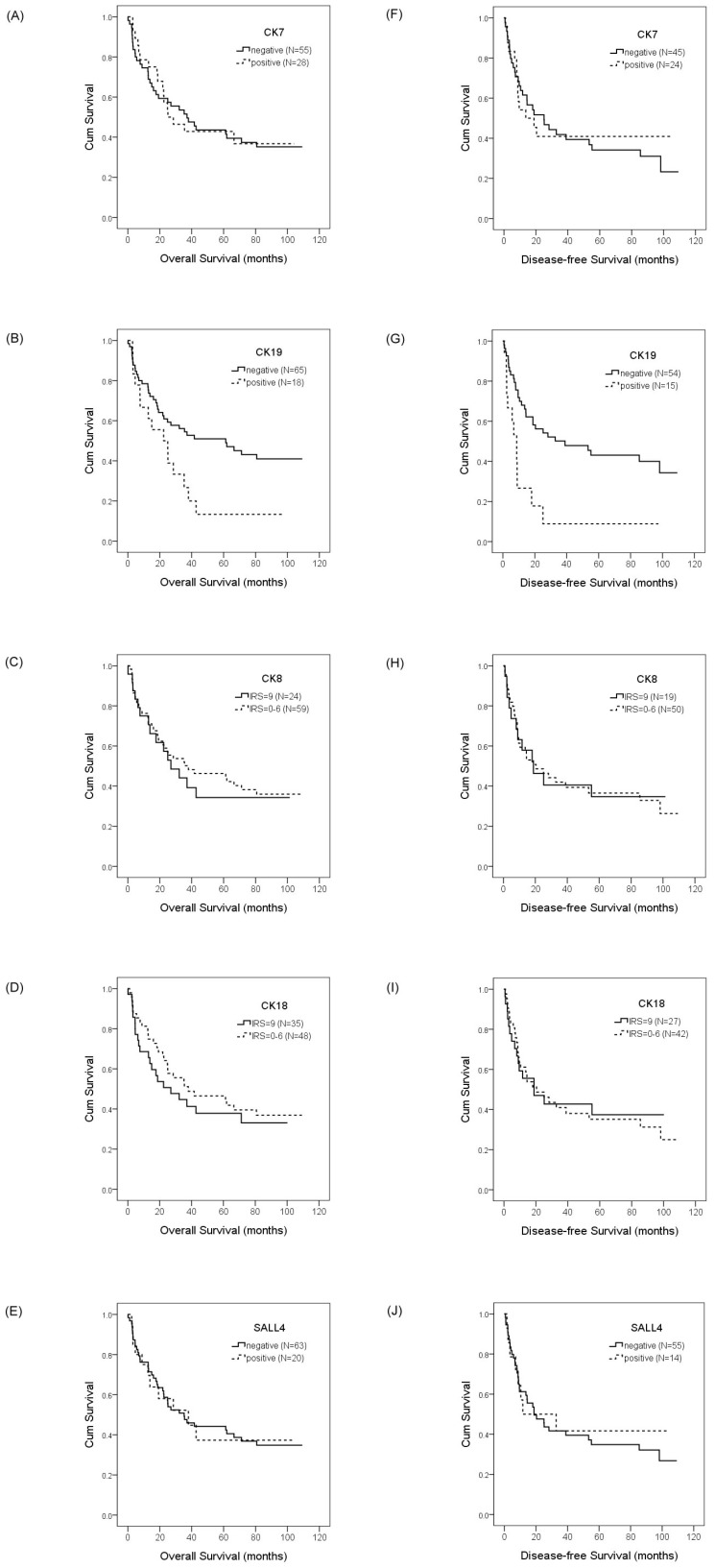

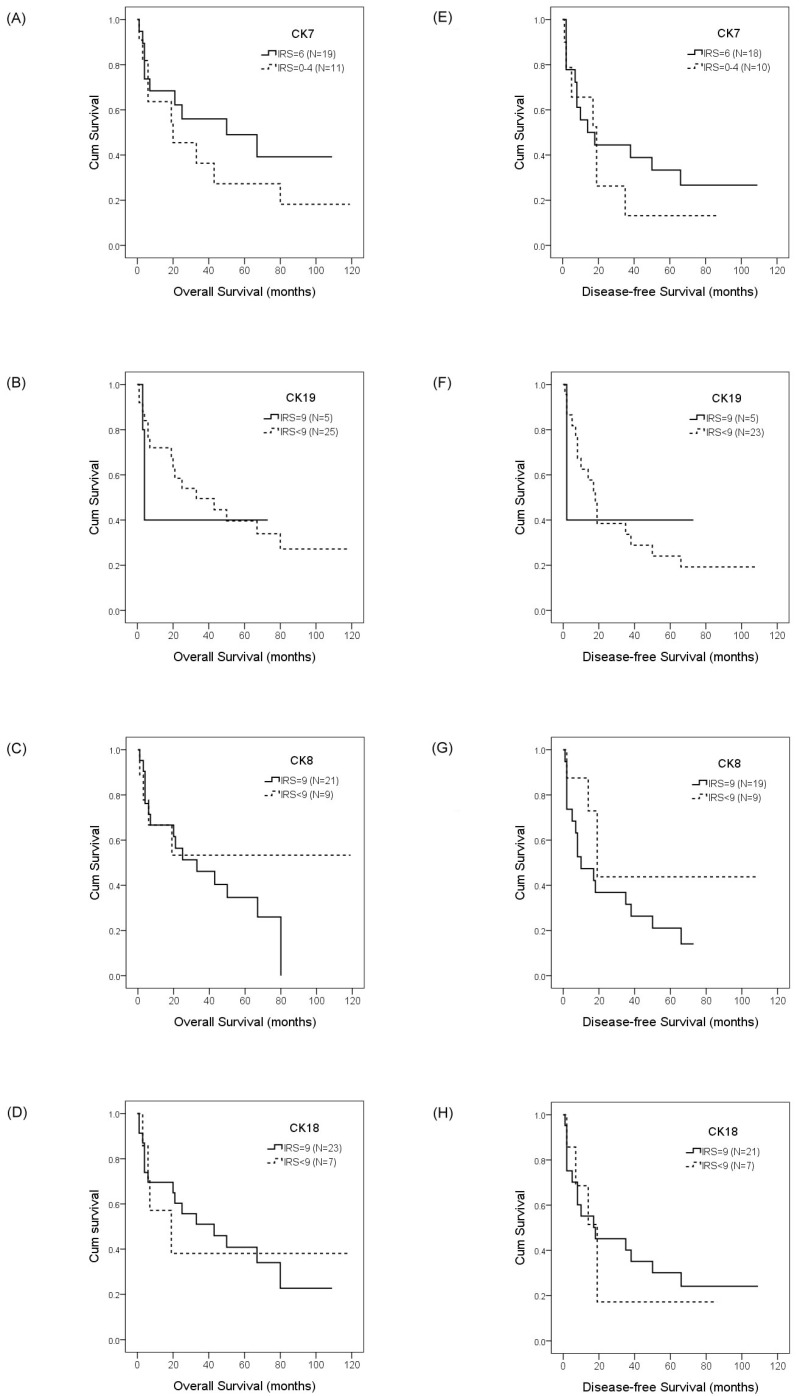

Expression of CKs and SALL4 as prognostic factors in HCC and ICC

To evaluate the prognostic value of CKs and SALL4 in HCC and ICC, we examined the correlation between the expression of CK7/19, CK8/18, and SALL4 and patient survival using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. Our data showed that HCC patients with a positive expression of CK19 exhibited shorter OS compared with negative expression (22.4 months vs. 61.3 months, p =0.028; Figure 3b), while the DFS was 8.7 months versus 39.0 months (p =0.001; Figure 3g). Our data also show that the expression of CK7, CK8, CK18, and SALL4 affect the OS and DFS of HCC patients, but without statistical significance (Figure 3). The expression of CK7, CK19, CK8 and CK18 may affect the OS and DFS of ICC patients, but without statistical significance (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Overall survival and disease-free survival rates of HCC patients with differential CK and SALL4 expression as estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. The overall survival rate in HCC patients with CK7 expression was less than patients without CK7 expression (25.1 months vs. 37.0 months, p =0.933)(A); with CK19 expression was less than patients without CK19 expression (22.4 months vs. 61.3 months, p =0.028)(B); with normal CK8 expression was less than patients with decreased CK8 expression (27.0 months vs. 38.0 months, p =0.692)(C); with normal CK18 expression was less than the patients with decreased CK18 expression (27.0 months vs. 38.0 months, p =0.442)(D); with SALL4 expression was greater than the patients without SALL4 expression (38.0 months vs. 35.3 months, p =0.999)(E). The disease-free survival rate in HCC patients with CK7 expression was less than the patients without CK7 expression (13.6 months vs. 25.1 months, p =0.784)(F); with CK19 expression was less than patients without CK19 expression (8.7 months vs. 39.0 months, p =0.001)(G); with normal CK8 expression was less than the patients with decreased CK8 expression (18.8 months vs. 20.4 months, p =0.930)(H); with normal CK18 expression was less than the patients with decreased CK18 expression (18.8 months vs. 20.4 months, p =0.854)(I); with SALL4 expression was less than the patients without SALL4 expression (11.7 months vs. 18.8 months, p =0.815)(J).

Figure 4.

Overall survival and disease-free survival rates of ICC patients with differential CK expression were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test. The overall survival rates in ICC patients with IRS=6 CK7 expression was greater than the patients with IRS<6 CK7 expression (50.0 months vs. 20.0 months, p =0.628)(A); with normal CK19 expression was less than the patients with decreased CK19 expression (4.0 months vs. 33.0 months, p =0.743)(B); with normal CK8 expression was less than the patients with decreased CK8 expression (33.0 months vs. > 50%, p =0.261)(C); with normal CK18 expression was greater than the patients with decreased CK18 expression (43.0 months vs. 19.0 months, p =0.953)(D). The disease-free survival rates in ICC patients with IRS=6 CK7 expression was less than the patients with IRS<6 CK7 expression (14.0 months vs. 19.0 months, p =0.848)(E); with normal CK19 expression was less than the patients with decreased CK19 expression (2.0 months vs. 18.0 months, p =0.854)(F); with normal CK8 expression was less than the patients with decreased CK8 expression (10.0 months vs. 19.0 months, p =0.146)(G); with normal CK18 expression was less than the patients with decreased CK18 expression (18.0 months vs. 19.0 months, p =0.789)(H).

Correlation between CK and SALL4 expression and hepatitis virus infection status in HCC

Based on the chi-square test, there was no significant difference between CK or SALL4 expression and HBV or HCV infection. The NBNC group was not statistically correlated with CK or SALL4 expression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation of CKs and SALL4 expression with hepatitis virus infection in HCC

| Viral status | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV (N, %) | HCV (N, %) | NBNC (N, %) | Total (N, %) | X2 | p | ||||||

| CK7 | 1.289 | .525 | |||||||||

| Negative | 21 | 70.0% | 16 | 59.3% | 19 | 73.1% | 56 | 67.5% | |||

| Positive | 9 | 30.0% | 11 | 40.7% | 7 | 26.9% | 27 | 32.5% | |||

| CK19 | 0.690 | .708 | |||||||||

| Negative | 22 | 73.3% | 22 | 81.5% | 21 | 80.8% | 65 | 78.3% | |||

| Positive | 8 | 26.7% | 5 | 18.5% | 5 | 19.2% | 18 | 21.7% | |||

| CK8 | 0.795 | .672 | |||||||||

| IRS 9 | 10 | 33.3% | 7 | 25.9% | 6 | 23.1% | 23 | 27.7% | |||

| IRS 0-6 | 20 | 66.7% | 20 | 74.1% | 20 | 76.9% | 60 | 72.3% | |||

| CK18 | 0.138 | .934 | |||||||||

| IRS 9 | 13 | 43.3% | 11 | 40.7% | 10 | 38.5% | 34 | 41.0% | |||

| IRS 0-6 | 17 | 56.7% | 16 | 59.3% | 16 | 61.5% | 49 | 59.0% | |||

| SALL4 | 4.130 | .127 | |||||||||

| Negative | 19 | 63.3% | 22 | 81.5% | 22 | 84.6% | 63 | 75.9% | |||

| Positive | 11 | 36.7% | 5 | 18.5% | 4 | 15.4% | 20 | 24.1% | |||

NBNC: viral infection-free

Comparison of clinicopathologic features between CK19-positive and -negative HCC

The results of an analysis of the relationship between CK19 expression and various clinicopathologic parameters are summarized in Table 3. Surprisingly we found that tumor size alone was associated with CK19 expression; the mean size of CK19-positive HCC was greater than CK19-negative HCC (10.2 cm vs. 7.4 cm, p=0.041). There was no significant difference between CK19 expression and HBV or HCV infection. The age, gender, smoking and alcohol consumption status, titer of α-fetoprotein, number of tumors, tumor grading, cirrhosis, vascular invasion, and metastasis were not statistically correlated with CK19 expression in HCC.

Table 3.

Comparison of clinicopathologic features between CK19-positive and CK19-negative HCC

| CK19 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | P value | |

| Age (years, mean±SD) | 63.7±13.4 | 59.7±14.6 | .267 |

| Gender (male:female) (male%) | 44:21 (67.7) | 10:8 (55.6) | .499 |

| Smoking (%) | 27 (43.5) | 6 (35.3) | .739 |

| Drinking (%) | 22 (35.5) | 6 (35.3) | 1.000 |

| Viral status (%) | .708 | ||

| HBV | 22 (33.8) | 8 (44.4) | |

| HCV | 22 (33.8) | 5 (27.8) | |

| NBNC | 21 (32.3) | 5 (27.8) | |

| AFP (ng/ml, mean±SD) | 28429.3±112825.1 | 17473.3±44124.4 | .689 |

| Tumor type (%) | .122 | ||

| Solitary | 52 (80.0) | 11 (61.1) | |

| Multiple | 13 (20.0) | 7 (38.9) | |

| Tumor size (cm, mean±SD) | 7.4±4.9 | 10.2±5.4 | .041* |

| Tumor grade (%) | .279 | ||

| Grade 1 | 4 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Grade 2 | 38 (58.5) | 8 (44.4) | |

| Grade 3 | 22 (33.8) | 9 (50.0) | |

| Grade 4 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (5.6) | |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 19 (29.2) | 4 (22.2) | .767 |

| Vascular invasion (%) | .462 | ||

| Absent | 24 (36.9) | 4 (22.2) | |

| Capsular vein invasion | 4 (6.2) | 1 (5.6) | |

| Portal vein tumor thrombosis | 37 (56.9) | 13 (72.2) | |

| Metastasis (%) | 9 (13.8) | 1 (5.6) | .683 |

| Expire (%) | 36 (55.4) | 15 (83.3) | .060 |

AFP: α-fetoprotein; NBNC: viral infection-free

Spearman's correlation analysis of CKs and SALL4 in HCC and ICC

We explored the association between expression among CK7/19, CK8/18, and SALL4 in HCC and ICC using Spearman's correlation analysis. In HCC, of all the markers examined, the only significant association was found between CK19 and SALL4 expression (Spearman rs = 0.359, p = 0.001) as well as CK8 and CK18 expression (Spearman rs = 0.783, p < 0.001). No correlation existed among the other markers. Therefore, the expression of CK19 was correlated with SALL4, while the expression of CK7, CK8, and CK18 was not associated with SALL4 expression in HCC (Table 4). In ICC, the test demonstrated that expression of CK19, CK8, and CK18 was strongly correlated, while expression of CK7 was not associated with other CKs. The expression of SALL4 was not included in this analysis because all 30 cases of ICC were SALL4-negative (Table 5). The correlation was significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Table 4.

Spearman's correlation analysis of CK and SALL4 expression in HCC

| CK7 | CK19 | CK8 | CK18 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK19 | Correlation Coefficient | .030 | |||

| p | .787 | ||||

| N | 83 | ||||

| CK8 | Correlation Coefficient | -.020 | .121 | ||

| p | .856 | .274 | |||

| N | 83 | 83 | |||

| CK18 | Correlation Coefficient | .103 | .062 | .783** | |

| p | .352 | .575 | <.001 | ||

| N | 83 | 83 | 83 | ||

| SALL4 | Correlation Coefficient | -.013 | .359** | .057 | .033 |

| p | .909 | .001 | .610 | .765 | |

| N | 83 | 83 | 83 | 83 |

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Table 5.

Spearman's correlation analysis of the CK expression in ICC

| CK7 | CK19 | CK8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK19 | Correlation Coefficient | .418* | ||

| p | .022 | |||

| N | 30 | |||

| CK8 | Correlation Coefficient | .421* | .512** | |

| p | .020 | .004 | ||

| N | 30 | 30 | ||

| CK18 | Correlation Coefficient | .453* | .570** | .750** |

| p | .012 | .001 | .000 | |

| N | 30 | 30 | 30 | |

* Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Discussion

In the current study, we determined the expression of CK7/19, CK8/18 and SALL4 in patients with HCC and ICC in Taiwan. The results demonstrated that CK7 and CK19 were expressed in 32.5% and 21.7% of 83 HCC cases, respectively. Despite being contrary to traditional dogma that CK7/19 is not expressed in hepatocytes and HCC, our data were in agreement with an earlier report that asserted CK7 and/or CK19 were/was expressed in 28% of Caucasian patients with HCC 22. We also notice that the expression of CK7/19 in HCC has recently been reported more commonly 23, 24. Of 83 HCC patients, 72.3% and 59.0% had decreased expression of CK8 and CK18, respectively. The results are in agreement with our previous study 5-7, suggesting that CK18 is modulated and down-regulated in human HCC. The frequency of SALL4 expression in HCC has in fact varied widely in different report, ranging from 1.3%-85% 25. Our data showed SALL4 expression to be 24.1% of 83 HCC patients. In the adjacent non-neoplastic liver, the hepatocytes and bile ducts did not stain for SALL4; the results are consistent with other publication 25. The expression of CK7/19 and SALL4 might indicate the stemness characteristics in HCC.

Considering the correlation between CK expression and patient survival in HCC, we found that only CK19 expression was significantly associated with reduced OS and DFS in HCC patients. Expression of other markers, including CK7, CK8, and CK18, might affect the survival outcome of HCC; however, there was no statistical significance. Recently, CK19 has been reported to be a key factor of aggressive progress and poor prognosis in HCC 23. The clinicopathological features associated with poor prognosis of CK19-positive HCC, including invasion and angiogenesis 23, increased tumor size, decreased tumor differentiation, metastasis, and microvascular invasion 26, as well as histologic features and TNM staging 27, and higher recurrence rate 22 were also reported. Surprisingly, our data revealed that tumor size was the only prognostic factor of CK19-positive HCC in Taiwan. Other clinical features, including titer of α-fetoprotein, HBV/HCV infection, tumor grading, cirrhosis, vascular invasion, and metastasis, were not correlated with CK19 expression in this study. Tumor size was strongly associated with cell proliferation ability, and epidermal growth factor-induced CK19 expression accompanied by increased growth ability in human HCC has been reported 28. Therefore, we suggest that poor prognosis of CK19-positive HCC might be associated with tumor size by activating the epidermal growth factor signal pathway.

Identification of CSCs and CSC-related therapeutic targets is necessary for improving HCC treatment outcomes. In addition to the correlation with poor prognosis of HCC, CK19 has also been reported as a CSC marker of HCC 18, 29. Because the association of CK and SALL4 expression has rarely been studied in HCC, we were interested to determine whether or not SALL4 expression in HCC is associated with the expression of other CKs in Taiwan. Based on Spearman's correlation analysis, the results showed that expression of CK19, but not CK7, CK8, and CK18, was associated with SALL4 expression in HCC. Few studies have shown that overexpression of SALL4 correlates with an increase in CK19 expression and markedly augment the size and number of CK19-branching structures 30, 31, and that SALL4-positive HCC is more frequently immunoreactive for CK19 32. In this study, we explored the combined detection of CK19 and SALL4 in human HCC, and showed that expression of CK19 was significantly associated with SALL4. Therefore, CK19 is a potent prognostic biomarker of HCC-CSC with stem cell characteristics, and is a therapeutic target for HCC. In addition to the CK19-SALL4 relationship, a strong associated expression between CK8 and CK18 in HCC was found in this study. The molecular mechanism underlying the associations between the expressions of markers in HCC is not clear, but is the focus of ongoing corollary studies.

A number of studies have demonstrated that elevated expression of SALL4 in tumors is associated with poor survival and resistance to chemotherapy of HCC patients 19, 25, 31-34; however, our data revealed that SALL4 expression is not significantly associated with OS and DFS of HCC patients in Taiwan. The discrepancy might due to the different interval of follow-up. There is a report that showed SALL4-positive HCC had worse short-term (< 1 year) DFS, but the long-term DFS or OS did not differ significantly between patients with SALL4-positive and -negative HCC 32. Because our follow-up interval was up to 120 months, it was reasonable to show that SALL4 expression is not significantly associated with OS and DFS long-term. In this study, we also found that the expression of CK and SALL4 did not correlate with HBV/HCV infection in HCC. The results were compatible with most published data 23, 26, 33.

In ICC, the expression of CK19, CK8, and CK18 was 100% in 30 ICC cases; however, 83.3%, 30%, and 23.3% of the 30 cases revealed decreased expression of CK19, CK8, and CK18, respectively. We also observed that all of the ICC cases had low or no expression of CK7 (IRS 0~6) when compared with normal bile duct epithelium and adjacent proliferative bile ducts (IRS=9). This finding was valuable for pathologic practice. Bile duct proliferation is often seen in liver diseases and mimics bile duct adenocarcinoma. Our finding may help pathologists discriminate bile duct proliferation from carcinoma and avoid a misdiagnosis. Even though numerous studies have indicated that CK7 is expressed in ICC, pre-malignant conditions, and normal biliary epithelium 35, 36, Zen et al. 37 reported that Tubulin b-III is more specific than CK7 for discriminating ICC from non-malignant biliary epithelium. Our data demonstrated that expression of CK7 was normal (IRS=9) in normal and proliferative bile ducts (100%), while all ICC patients had low (IRS 1-6 [80%]) or negative (IRS=0 [20%]) expression of CK7. Therefore, down expression of CK7 might be a suitable landmark for discriminating ICC from non-malignant biliary epithelium. At the tissue level, CKs have rarely been studied with respect to roles in association with patient survival in ICC. In this study, we reported that there was no significant correlation between OS and DFS and lower CK expression of ICC in Taiwan. Interestingly, we also found that the expression of CK8, 18, and 19 was significantly correlated in ICC, but CK7 expression was independent to other CKs.

Several CSC markers have been reported in ICC, but SALL4 is not mentioned in those publications 20, 21. In our study, the expression of SALL4 was not found in all 30 ICC patients, therefore the association between SALL4 expression and ICC patient survival could not be assessed. The bioinformation about SALL4 in ICC is limited; however, two main reports have indicated that ICC expresses SALL4. Oikawa et al. 31 reported that four of five cholangiocarcinoma specimens expressed SALL4, but bioinformatics analyses relating SALL4 expression to survival of patients has not been reported. Deng et al. 38 reported SALL4-positive immunoreactivity in 58% of 175 ICC cases, and strong SALL4-positive cases had shorter overall survival; however, SALL4 protein was expressed mainly in the cytoplasm rather than the nuclei. Recently, Zhu et al. 39 reported that knockdown of SALL4 inhibits malignant phenotypes of ICC cells by regulating PTEN/PI3K/Akt and Wnt/β-catenin signaling and repressing the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process. Our data in Taiwan differs from the publications in Japan and China; whether or not the discrepancies are due to ethnicity or other factors warrants further research.

Conclusions

Expression of CK7/19 and SALL4 in HCC patients of Taiwan was confirmed. The expression of CKs and SALL4, with the exception of CK19, was not associated with HBV/HCV infection and survival of HCC patients. A significant correlation between SALL4 and CK19 expression in HCC, as well as poor OS and DFS in CK19-positive HCC patients of Taiwan, supports the recent literature that SALL4 and CK19 may be useful markers of stemness in hepatic stem/progenitor cells and HCCs. For the first time, we have reported that ICC has decreased or negative CK7 expression and the expression of SALL4 was also negative. The expression of CK8, 18, and 19 was significantly correlated, and CK7 expression was independent of other CKs; however, there was no significant correlation between CK expression and survival of ICC patients in Taiwan.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate Ms. Chen, You-Yin for her skillful assistance in the laboratory. We also appreciate the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) Biobank and Taiwan Liver Cancer Network (TLCN) for providing the samples.

Funding

This work was supported by the Chang Bing Show Chwan Memorial Hospital [Grant number RD-105005].

Abbreviations

- CK

Cytokeratin

- CSC

Cancer stem cell

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- ICC

Intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- IRS

Immunoreactive score

- NBNC

Viral infection-free

- OS

Overall survival

- PLC

Primary liver cancer

- SALL4

Sal-like protein 4.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theise ND, Curado MP, Franceschi S. Tumours of the liver and intrahepatic bile ducts. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. pp. 195–261. [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Eyken P, Sciot R, van Damme B. et al. Keratin immunohistochemistry in normal human liver. Cytokeratin pattern of hepatocytes, bile ducts and acinar gradient. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1987;412:63–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00750732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai YS, Thung SN, Gerber MA. et al. Expression of cytokeratins in normal and diseased livers and in primary liver carcinomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989;113:134–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su B, Pei RJ, Yeh KT. et al. Could the cytokeratin molecule be modulated during tumor transformation in hepatocellular carcinoma? Pathobiology. 1994;62:155–9. doi: 10.1159/000163897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu YH, Pei RJ, Yeh CC. et al. The alteration of cytokeratin 18 molecule and its mRNA expression during tumor transformation in hepatoma. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol. 1997;96:243–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng CC, Liu YH, Ho CC. et al. The influence of plectin deficiency on stability of cytokeratin 18 in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Mol Histol. 2008;39:209–16. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu YH, Ho CC, Cheng CC. et al. Cytokeratin 18-mediated disorganization of intermediate filaments is induced by degradation of plectin in human liver cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;407:575–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu YH, Cheng CC, Ho CC. et al. Plectin deficiency on cytoskeletal disorganization and transformation of human liver cells in vitro. Med Mol Morphol. 2011;44:21–6. doi: 10.1007/s00795-010-0499-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng CC, Lai YC, Lai YS. et al. Transient knockdown-mediated deficiency in plectin alters hepatocellular motility in association with activated FAK and Rac1-GTPase. Cancer Cell Int. 2015;15:29–36. doi: 10.1186/s12935-015-0177-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng CC, Chao WT, Liao CC. et al. Plectin deficiency in liver cancer cells promotes cell migration and sensitivity to sorafenib treatment. Cell Adh Migr. 2018;12:19–27. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2017.1288789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ang SF, Ng ES, Li H. et al. The Singapore Liver Cancer Recurrence (SLICER) Score for relapse prediction in patients with surgically resected hepatocellular carcinoma. PLOS One. 2015;10:e0118658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Tsubota A. et al. Risk factors for tumor recurrence and prognosis after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:19–25. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930101)71:1<19::aid-cncr2820710105>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma S. Biology and clinical implications of CD133(+) liver cancer stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN. et al. Significance of CD90 tcancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:153–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo Y, Tan Y. Prognostic value of CD44 expression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2016;16:47–55. doi: 10.1186/s12935-016-0325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashita T, Ji J, Budhu A. et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1012–24. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H, Choi GH, Na DC. et al. Human hepatocellular carcinomas with "Stemness"-related marker expression: keratin 19 expression and a poor prognosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1707–17. doi: 10.1002/hep.24559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yong KJ, Gao C, Lim JS. et al. Oncofetal gene SALL4 in aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2266–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardinale V, Renzi A, Carpino G. et al. Profiles of cancer stem cell subpopulations in cholangiocarcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:1724–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kokuryo T, Yokoyama Y, Nagino M. Recent advances in cancer stem cell research for cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:606–13. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durnez A, Verslype C, Nevens F. et al. The clinicopathological and prognostic relevance of cytokeratin 7 and 19 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. A possible progenitor cell origin. Histopathology. 2006;49:138–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takano M, Shimada K, Fujii T. et al. Keratin 19 as a key molecule in progression of human hepatocellular carcinomas through invasion and angiogenesis. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:903–12. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2949-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SH, Lee JS, Na GH. et al. Immunohistochemical markers for hepatocellular carcinoma prognosis after liver resection and liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2017;31:e12852. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park H, Lee H, Seo AN. et al. SALL4 Expression in Hepatocellular Carcinomas Is Associated with EpCAM-Positivity and a Poor Prognosis. J Pathol Transl Med. 2015;49:373–81. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2015.07.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Govaere O, Komuta M, Berkers J, Spee B, Janssen C, de Luca F. et al. Keratin 19: a key role player in the invasion of human hepatocellular carcinomas. Gut. 2014;63:674–85. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng J, Zhu R, Chang C. et al. CK19 and glypican 3 expression profiling in the prognostic indication for patients with HCC after surgical resection. PLOS One. 2016;11:e0151501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoneda N, Sato Y, Kitao A. et al. Epidermal growth factor induces cytokeratin 19 expression accompanied by increased growth abilities in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2011;91:262–72. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawai T, Yasuchika K, Ishii T. et al. Keratin 19, a cancer stem cell marker in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3081–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oikawa T, Kamiya A, Kakinuma S. et al. Sall4 regulates cell fate decision in fetal hepatic stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1000–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oikawa T, Kamiya A, Zeniya M. et al. Sal-like protein 4 (SALL4), a stem cell biomarker in liver cancers. Hepatology. 2013;57:1469–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.26159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibahara J, Ando S, Hayashi A. et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of SALL4-immunopositive hepatocellular carcinoma. Springerplus. 2014;3:721–9. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin F, Han X, Yao SK. et al. Importance of SALL4 in the development and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2837–43. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i9.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung YK, Jang K, Paik SS. et al. Positive immunostaining of Sal-like protein 4 is associated with poor patient survival outcome in the large and undifferentiated Korean hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2016;91:23–8. doi: 10.4174/astr.2016.91.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zen Y, Sasaki M, Fujii T. et al. Different expression patterns of mucin core proteins and cytokeratins during intrahepatic cholangiocarcinogenesis from biliary intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct-an immunohistochemical study of 110 cases of hepatolithiasis. J Hepatol. 2006;44:350–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ainechi S, Lee H. Updates on precancerous lesions of the biliary tract: Biliary precancerous lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1285–9. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0396-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zen Y, Britton D, Mitra V. et al. Tubulin β-III: a novel immunohistochemical marker for intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2014;65:784–92. doi: 10.1111/his.12497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deng G, Zhu L, Huang F. et al. SALL4 is a novel therapeutic target in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:27416–26. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu L, Huang F, Deng G. et al. Knockdown of Sall4 inhibits intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cell migration and invasion in ICC-9810 cells. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:5297–305. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S107214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]