Abstract

Rationale: Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are emerging as a novel therapeutic strategy for the acute ischemic stroke (AIS). However, the poor targeted migration and low engraftment in ischemic lesions restrict their treatment efficacy. The ischemic brain lesions express a specific chemokine profile, while cultured MSCs lack the set of corresponding receptors. Thus, we hypothesize that overexpression of certain chemokine receptor might help in MSCs homing and improve therapeutic efficacy. Methods: Using the middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model of ischemic stroke, we identified that CCL2 is one of the most highly expressed chemokines in the ipsilateral hemisphere. Then, we genetically transduced the corresponding receptor, CCR2 to the MSCs and quantified the cell retention of MSCCCR2 compared to the MSCdtomato control. Results: MSCCCR2 exhibited significantly enhanced migration to the ischemic lesions and improved the neurological outcomes. Brain edema and blood-brain barrier (BBB) leakage levels were also found to be much lower in the MSCCCR2-treated rats than the MSCdtomato group. Moreover, this BBB protection led to reduced inflammation infiltration and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. Similar results were also confirmed using the in vitro BBB model. Furthermore, genome-wide RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis revealed that peroxiredoxin4 (PRDX4) was highly expressed in MSCs, which mainly contributed to their antioxidant impacts on MCAO rats and oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD)-treated endothelium. Conclusion: Taken together, this study suggests that overexpression of CCR2 on MSCs enhances their targeted migration to the ischemic hemisphere and improves the therapeutic outcomes, which is attributed to the PRDX4-mediated BBB preservation.

Keywords: Mesenchymal stromal cells, CCL2/CCR2, blood brain barrier, endothelium, PRDX4

Introduction

Stroke is the leading cause of mortality and disability worldwide, while the available therapeutic options are limited 1. Intravenous administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) has become the typical curative treatment for acute stroke patients since its approval by FDA in 1996 2. However, the tPA application is restricted by a narrow time window (4.5 hours within onset) and its relative high risk of brain hemorrhage 3, 4. In the United States, it is estimated that only about 5.2% of the AIS patients received tPA treatment, with some higher data in other systems 3, 5. Recently, endovascular intervention seems to extend the therapeutic window to 12 hours post-stroke, nonetheless patients who do receive the rapid reperfusion therapy still get long-term disability 6, 7. Thus, the investigation of additional therapies such as cell therapy for the acute stage and brain perfusion is compelling.

BBB breakdown and the resulting inflammatory infiltration are two major factors predictive of worse prognosis and outcomes 8, 9. Tight junction (TJ) - sealed endothelial cells are the primary barrier for the blood-born products to enter the cerebral parenchymal 10, 11. The current view is that ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury initiates TJ disassembly, activates the innate immune responses and challenges BBB with oxidative stress 12, 13. Upon ischemia attack, stressed endothelial cells and surrounding astrocytes release a series of chemical mediators like chemokines, tumor necrosis factors and interleukins, exacerbating the BBB breakdown 14, 15. Consequently, the compromised BBB permits the transendothelial movement of neutrophils/macrophages, causing additional detrimental effects and leading to a vicious circle. Therefore, maintaining the BBB integrity simultaneously blocking the detrimental effects of inflammatory infiltration may serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for cerebral I/R injury.

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) represent a promising cell-based therapy option for the post-stroke treatment 16. Even though there is emerging evidence suggesting that MSCs transplantation enhance functional recovery and improve neurological outcomes after stroke 17, 18, certain obstacles still limit their application and therapeutic efficacy. For example, it is commonly reckoned that the ability of MSCs to home and engraft into the target lesions determine their therapeutic efficacy 19, 20. However, isolated MSCs were found gradually lost their homing capacity to the targeted lesions during continuous passage 21, 22. In an experimental MCAO model, only a small portion of the intravenously injected MSCs enter the ischemic hemisphere through the disrupted BBB, the majority would be trapped in lungs and spleens 21, 23. Therefore, strategies for enhancing infused MSCs homing to the ischemic brain might benefit the therapeutic promotion.

The physiological and regulatory mechanisms underlying this homing process are not fully understood 24. It is commonly hypothesized that the injured tissues express and secrete specific chemokine ligands to mediate MSCs trafficking and infiltrating to the ischemic lesions, as is the case of monocytes recruitment to the site of inflammation 25. Recent evidences suggest that focal cerebral ischemia triggers chemokines expression and release, such as CCL2, by astrocytes, microglia and endothelial cells, which facilitates the transendothelial migration of immune cells and mediates the BBB disruption 26, 27. The CCL2/CCR2 interaction is also found essential for the therapeutic homing of intravascularly delivered neural stem cells 28. However, cultured MSCs are detected extremely low expression of certain surface receptors during continuous passage, resulted in loss of homing capacity 29, 30. In this study, we genetically modified MSCs to express CCR2 on the cell surface and hypothesized they would improve the post-stroke neurological recovery upon the engraftment.

Methods

Experimental Animals and Stroke Models

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of Sun Yat-Sen University. Male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats weighting 220g-250g were assigned randomly to different groups using a random number table. We have made all efforts to minimize the animal suffering. All animals were anesthetized by 1.5% isoflurane in a 30% O2/69% N2O mixture using face mask. Stroke model was induced by occlusion of one-side middle cerebral artery with silicone-coated sutures for 90 minutes as previously described 31. After surgery, the animals were placed in clean cages on a temperature-controlled heating block to maintain a body temperature of 37°C and monitored for respiration and signs of distress during recovery.

Transplantation Procedures

Our experimental design consisted of 5 groups: Group 1, sham group, Group 2, PBS alone (without MSCs administration), Group 3, MSCnaive transplantation group (2.0 x106), Group 4, MSCdtomato transplantation group (2.0x106), and Group 5, MSCCCR2 transplantation group (2.0 x106). All injections were done 24h after MCAO and cells were suspended in 0.5 ml of medium via the caudal vein.

Behavioral Tests

Neurological deficit was evaluated in all rats 1 day, 4 days and 7 days after MCAO in a blinded fashion. The experimenter was blinded to the group allocation and evaluated the neurological deficits using neurological score as described by Menzies: 0 - no apparent neurological deficits; 1 - contralateral forelimb flection, a mild focal neurologic deficit; 2 - decreased grip of contralateral forelimb, a moderate focal neurologic deficit; 3 - contralateral circling upon pulling by tail, a severe focal deficit; 4 - spontaneous contralateral circling 32. To evaluate the motor functional recovery, grip strength test and adhesive removal test were performed 4 days and 7days post-stroke as previously described 33, 34. The investigator was blinded to the experimental groups to perform the evaluation and conducted the statistical analysis.

Quantification of Infarct Volume

The fresh brains were removed and sliced into 1mm-thick sections. The slices were then stained with a 2% solution of 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) at 37°C for 30 min. The infarction area of each brain slice was measured by Image J analysis software. The infarct volumes were expressed (with correction for the edema) as a percentage of total hemispheres.

Evans Blue Dye Extravasation

Leakage of Evans blue dye (EBD, Sigma-Aldrich) in the ischemic brain tissue indicative of BBB disruption was analyzed 4 days after MCAO (Sham and PBS group) or 3 days after MSCs treatment (MSCnaive, MSCdtomato and MSCCCR2 group) using EBD. 2% Evans blue in normal saline (6 mL/kg BW, 150 L) was intravenously injected and allowed a circulation of 3 hours before the scarification. 1 ml of 50% trichloroacetic acid solution was added to the collected brain tissue to extract the EBD. To harvest the supernatant, centrifuge the mixture at 15,000g for 15 minutes and dilute it with 4-fold ethanol. The amount of EBD in the ischemic tissue was quantified at 610 nm according to a standard curve.

Brain Water Content

Rats were sacrificed 4 days after MCAO using a high dose of chloral hydrate (10%) anesthesia. The weights of brain samples were measured before and after dehydration respectively at 95°C for 24 hours. Brain water content was calculated by the equation: Percentage of brain water content = ([wet tissue weight-dry tissue weight]/wet tissue weight) *100%.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) Staining

Brain samples of each group were collected, fixed using transcardial perfusion and immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Standard streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase complex was used in IHC staining 35. The percentage number of Ly6G-positive or CD68-positive cells were determined in high-power fields (×200) of each brain slices. Images were analyzed using ImageJ. A minimum 500 cells per slice were counted. The utilized primary antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Measurement of Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Activity

At 3 days after MSC injection, brain tissues were collected and homogenized in 0.5% cetyltrimethylammonium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich). The insoluble tissues were passed through a nylon mesh and subjected to centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. Then we harvested the supernatant. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was measured using the MPO kit (Jiancheng, Nanjing, China), according to the recommended protocols.

ROS Assessment and Oxidative Chemistry Biomarkers

The in vivo ROS production was visualized on frozen rat brain sections 4 days after MCAO or 3 days after MSCs infusion using dihydroethidium (DHE; Sigma-Aldrich; 2 mM stock) staining, as previously described 36. Meanwhile, the general level of apoptosis in the ischemic hemisphere was also observed by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining on brain slices, using the TUNEL in situ cell death detection kit (Roche).

Besides that, total intracellular ROS levels were detected using fluorescent probes, CellROX, and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies).

Cell Culture and Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) Treatment

For MSCs collection, human bone marrow aspirates were obtained, along with their informed consents, from five independent healthy donors. MSCs were isolated from the bone marrow, cultured and identified the characteristics as previously described 37, 38.

The transformed mouse brain endothelial cell line bEnd.3 was used for in vitro BBB model. The cells were maintained as described elsewhere 39. The oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) and reoxygenation was used to mimic the cerebral ischemia-reperfusion damage in vitro. Briefly, the cell plates were placed in an anaerobic chamber (STEMCELL Technologies) at 37°C and the cell medium was replaced with salt buffer without glucose as well. 4 hours later, the cultural condition was switched to normal state.

Transduction of Vectors

The lentiviral expression vectors applied in this study were designated as pLV/puro-EF1a-CCR2-T2A-dtomato and pLV/puro-EF1a-dtomato. Lentiviruses particles were harvested from 293FT cells according to the manufacturer's instructions 40. MSCs (passage 3) from the same donor were transduced with CCR2 or control dtomato vector to avoid the effects of different genetic backgrounds. Three days after transduction, MSCCCR2 and MSCdtomato were sorted using FACS (Influx, Becton Dickinson).

Small Interfering RNA Knockdown

In vitro silencing of PRDX4 in MSCCCR2 was performed as previously described 41, using two sets of shPRDX4. shPRDX4-1: CCACACTCTTAGAGGTCTCTT; shPRDX4-2: GGCTGGAAACCTGGTAGTGAAA. MSCCCR2 (1×105 cells) were transfected with 20nM shPRDX4-1, shPRDX4-2 and scramble shRNA respectively using a commercial kit (Ribobio, Shanghai, China) after culture in 12-well plate overnight.

Transendothelial Diffusion

The endothelial permeability was assessed by measuring the diffusion of sodium fluorescein (Sigma-Aldrich) through the bEnd.3 monolayer using a method previously described by Perriere and colleagues 42. Endothelial cells were plated on 12-well Transwell polyester membranes (Corning Inc.) coated with collagen I (Sigma-Aldrich) and medium containing Na-F (1μM) was loaded onto the luminal side of the upper chamber and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Then, samples were removed from the lower compartment and examined using a fluorescence multi-well plate reader.

Migration Assays

The migrative capacity of MSCs was evaluated using an 8μm-pore transwell chamber system (Millipore). MSCs were seeded in the upper chamber (2.0 x 105 per well), while the lower chamber was loaded with recombinant CCL2 (50 ng/ml hCCL2 or 100 ng/ml rCCL2) or OGD-treated bEnd.3 cells (4.0 x 105 per well). After 4 hours of co-culture, we swabbed the MSCs remaining on the upper surface and stained the filters with 0.1% crystal violet. MSCs migrated to the lower surface were counted under microscopy.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescent staining, cells attached to the glass slides or brain sections harvested were fixed for 20 min with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, blocked for 30 min with PBS-3% BSA and finally incubated with proper primary and secondary antibodies in the dark (listed in Supplementary Table 2). Nuclei visualization was subjected to DAPI staining for 3 min. Images were acquired under the fluorescence microscopy or using an LSM800 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA from harvested brain tissue or cell lysates was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. QRT-PCR was performed using the SYBR Green qRT-PCR SuperMix (Roche) and detected by a Light Cycler 480 Detection System (Roche) as previously described 43. Each targeted mRNA level was normalized with respect to that of GAPDH. The sequences of primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Western Blotting

For Western blotting, cells or brain tissues were collected and lysed in 1×RIPA buffer. After centrifugation at 15,000 g for 5 min at 4 °C, we collected the supernatant as the protein lysate. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a 0.45-μm pore-sized polyvinylidenedifluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA and then incubated with certain primary and secondary antibodies. The utilized primary and secondary antibodies are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Flow Cytometry

MSCs were incubated for 30min with the appropriate antibody (Supplementary Table 3) in the dark at 4°C, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. All flow cytometric analyses were conducted with Gallios (Beckman Coulter) flow cytometers and the data were analyzed using the Kaluza (Beckman Coulter) software packages.

ELISA Assay

The concentration of PRDX4 in MSC culture medium was measured using commercial ELISA assay according to the instructions of manufacturer (Abnova, Taiwan).

Computational Analysis of RNA-seq

Genome-wide RNA-seq analysis of MSCs from three different donors was conducted in our previously published paper 44, which has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. SRP095307). Using DAVID Gene Functional Classification Tool (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) and Gene Ontology (GO) database (GO_0006979: response to oxidative stress), we explored the biological functions of the gene list and screened for antioxidant-related genes. Then, we log2-transformed all expression values of the selected antioxidant-related genes log2 (RPKM + 1), where RPKM is the number of reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads. The transformed values of RPKM were scaled by performing Z-score normalization within a group for the convenience of comparison between biological replicated experiments groups. A heat map was drawn with package R (version 3.1.1).

Extravascular IgG Deposition

For the extravasation of endogenous IgG molecules, the coronal brain sections were incubated with fluorescent secondary antibody against rat (Vector laboratories) for 1h as previously reported 45, 46. The IgG signal outside CD31+ vessels were quantified using Image J after being subjected to the threshold process.

Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as the mean ± S.E.M. from at least three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare mean responses among the treatments. SPSS Version 14.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA) was used for all analyses. P-value < 0.05(*) was considered significant.

Results

CCL2 expression following cerebral ischemia and reperfusion

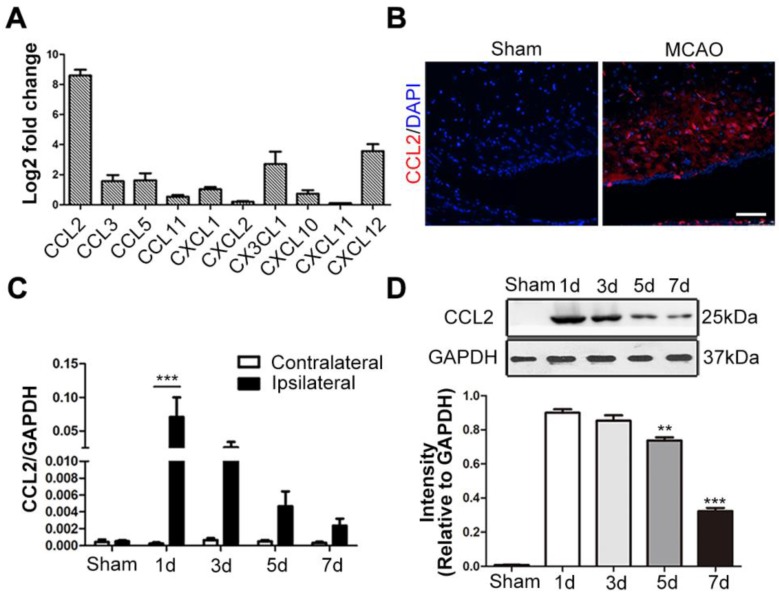

Since the chemokine/chemokine receptor axis is indispensable for MSCs migration, we detected the mRNA expression levels of various neuroinflammation-related chemokines secreted by the ischemic brain tissue, including CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, CCL11, CXCL1, CXCL2, CX3CL1, CXCL10, CXCL11 and CXCL12 47-49. Among these chemokines, CCL2 expression exhibited the most significant change 24h post-stroke, when compared to the contralateral hemisphere (Figure 1A). In situ immunofluorescence staining also confirmed its intense upregulation in the ischemic hemisphere (Figure 1B). Additionally, the highest levels of both CCL2 mRNA and protein expressions were observed at 24h post-stroke through the time-course analysis (Figure 1C-D).

Figure 1.

CCL2 expression following brain ischemia and reperfusion. (A) The mRNA extract from both contralateral and ipsilateral hemisphere were subjected to quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. Various chemokines related to CNS inflammatory responses were analyzed. CCL2 showed significant change fold in ipsilateral hemisphere compared to the contralateral control 24h after MCAO. n = 3. (B) Representative immunostaining images of sham-operated and MCAO rat brain sections stained for anti-CCL2 (red) antibody and DAPI (blue) for visualizing the nuclei. Scale bars: 75μm. (C) In the ischemic hemisphere, CCL2 mRNA expression level was detected peak at 24h post-MCAO through qRT-PCR analysis. n = 3. (D) Representative immunoblots depicted the protein expression level of CCL2 in the ischemic hemisphere. The experiment was repeated three times with tissue lysates of independent rats. Bar graphs displayed the gray intensity analysis of the representative blots. n = 3. All data are expressed as means ± SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and n.s. is non-significant.

Genetic modification of MSCs overexpressing CCR2

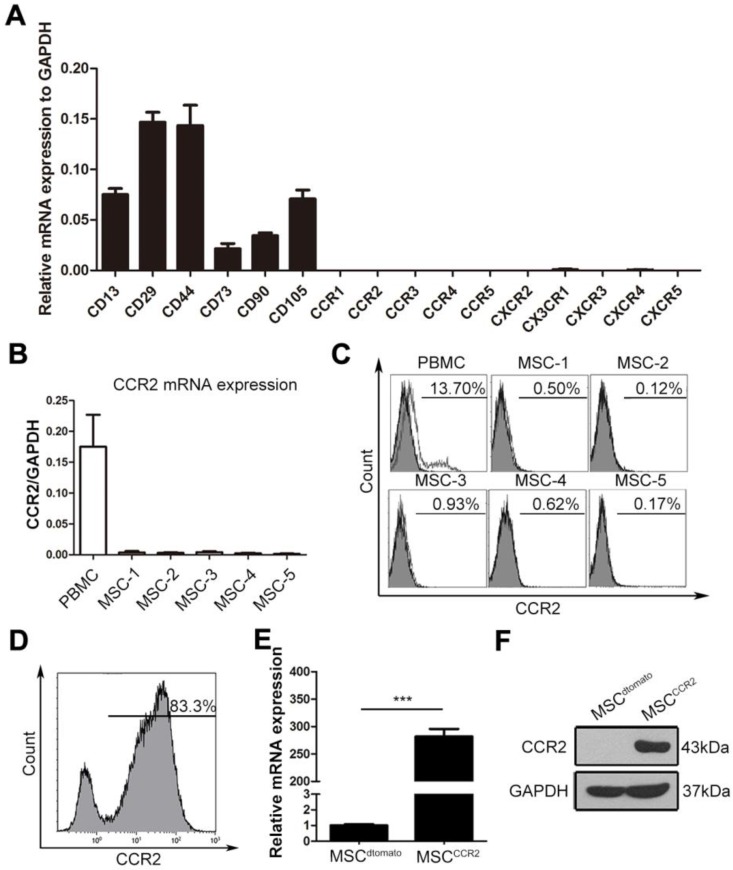

We then examined a set of C-C motif receptors, CXC motif chemokine receptors and C-X3-C motif chemokine receptor expression in cultured MSCs. The qRT-PCR assay showed the mRNA levels of these chemokine receptors were extremely low in the fourth-passage MSCs (Figure 2A), indicating the enforced expression of certain chemokine receptor might enhance MSCs homing capacity. High levels of CCL2 secreted by ischemic lesions indicated the potential requirement of its corresponding receptor CCR2. Thus, the CCR2 expression levels were reconfirmed in fourth-passage MSCs isolated from five independent donors using both - qRT-PCR and flow cytometry analysis. Compared with the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), MSCs at passage four expressed little CCR2 mRNA or surface CCR2 protein (Figure 2B-C). To increased MSCs homing capacity, MSCs were transduced with lentiviral vectors encoding CCR2 (referred to as MSCCCR2) or dtomato (referred to as MSCdtomato) (Figure S1). Cells expressing dtomato fluorescence were isolated by flow cytometry and determined CCR2 expression in mRNA and protein levels (Figure 2D-F). Furthermore, we detected whether the transgenic manipulations affected the intrinsic characteristics of MSCs. Flow cytometry analysis showed both MSCdtomato and MSCCCR2 expressed the typical MSC marker profile (CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90, CD105 and CD166) and lacked hematopoietic marker (CD34 and CD45) expression (Figure S2A). For the multilineage differentiation potential, transfected MSCs were subjected to adipogenic-induction medium or osteogenic-induction medium for three weeks. Alizarin red S staining and oil red O staining were conducted to confirm the osteogenic and adipogenic capacity of modified MSCs, respectively (Figure S2B). Adipogenic and osteogenic markers of differentiated MSCs were also detected by PCR (Figure S2C). These data suggest we have successfully overexpressed CCR2 in cultured MSCs without altering their biological characteristics.

Figure 2.

Expression profiling of chemokine receptors in cultured MSCs suggest genetically overexpressing CCR2. (A) The expression of CC and CXC chemokine receptors on fourth-passage (P4) MSCs were analyzed by qRT-PCR of mRNA samples from three independent donors. Surface markers including CD13, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD105, and CD90 were served as the positive control. n = 3. (B) The relative mRNA expression of CCR2 normalized to GAPDH was detected in MSCs from additional five independent donors by qRT-PCR analysis. (C) Flow cytometry analysis depicted that cultured MSCs (P4) were negative for CCR2 expression when compared with the positive control PBMCs. (D) MSCs with expression of CCR2 were isolated by FACS sorting. (E and F) CCR2 expression was confirmed by qRT-PCR (E) and western blotting (F). All data are expressed as means ± SEM; ***p < 0.001, and n.s. is non-significant.

CCR2-modified MSCs possess increased migrative capacity towards CCL2 in vitro and to the ischemic lesions in vivo

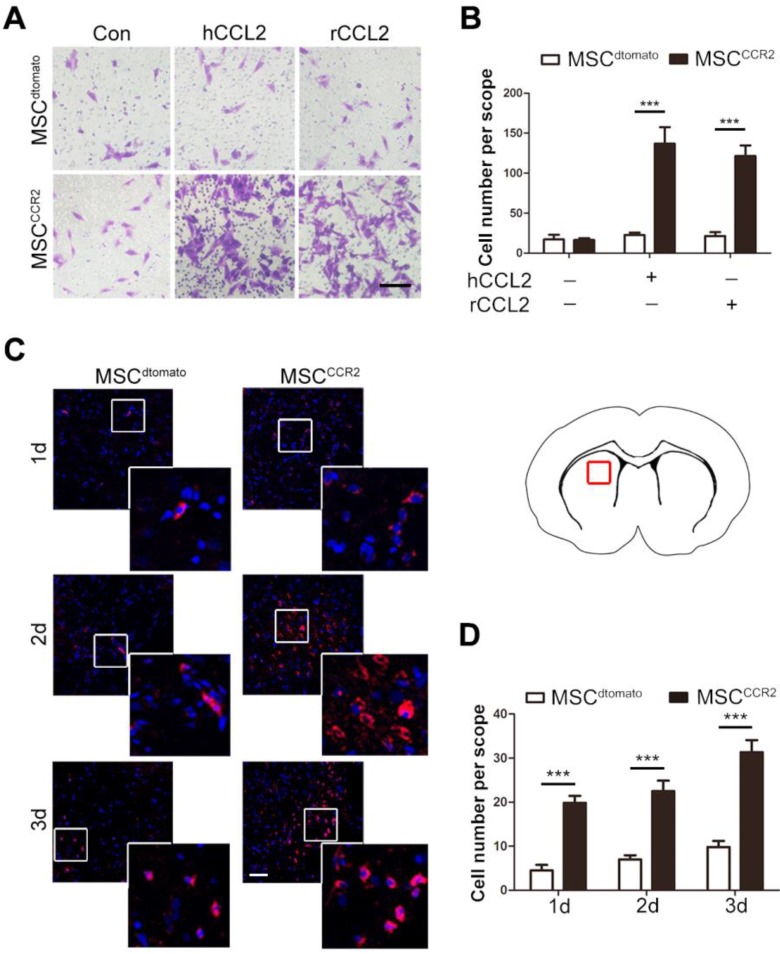

To further examine the homing capacity of CCR2-modified MSCs, we first observed MSCCCR2 migration towards the recombinant human CCL2 (hCCL2, 50ng/ml) and rat CCL2 (rCCL2, 100ng/ml) in the lower chamber, respectively. In vitro transwell assay showed only MSCCCR2 responded to CCL2 stimulation, while the number of MSCdtomato passing through the transwell membrane pores generally did not change. Besides that, MSCdtomato and MSCCCR2 showed similar but relatively low migration without exogenous CCL2 treatment (Figure 3A-B).

Figure 3.

CCR2-modified MSCs possess increased migrative capacity towards CCL2 in vitro and to ischemic lesion in vivo. (A) Transwell invasion assays were performed to detect the in vitro migration of transfected MSCdtomato and MSCCCR2 to recombinant human CCL2 (hCCL2) and rat CCL2 (rCCL2), respectively. Scale bar: 100μm. (B) Quantification of migrated cells showed the increase of MSCs stained by 0.1% crystal violet in CCR2 group compared to dtomato control. n = 4. (C) Representative confocal images of injected dtomato-positive MSCs located in the affected hemisphere at 1d, 2d and 3d post-injection. Scale bar: 200μm. (D) Quantification of migrated cells was conducted by counting dtomato-positive cells in six randomized fields. The experiments were performed in six replicates. All data are expressed as means ± SEM; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and n.s. is non-significant.

The data in Figure 1 have demonstrated the intense upregulation of CCL2 in ischemic brain tissue 24h post-stroke. Then, we investigated whether the enforced expression of CCR2 in MSCs could enhance their chemotaxis towards the ischemic lesions, presumably induced by tissue-specific secretion of CCL2. The brain slice samples were collected from MSCdtomato and MSCCCR2 group 1, 2 and 3 days post-injection. The considerable increase of dtomato-positive cells were detected in MSCCCR2 group when compared with MSCdtomato group (Figure 3C-D). Additionally, we reconfirmed cell identities of the detected dtomato+ cells. These cells were found expressing stem cell marker PDGFRα, but not NeuN or GFAP, convincing that these dtomato+ cells were transplanted MSCs (Figure S3). In sum, CCR2 overexpression obviously enhances the chemokine-mediated chemotaxis of MSCs in vitro and in vivo.

Transplantation of MSCCCR2 ameliorates ischemic lesions in vivo and enhances neurological functional recovery

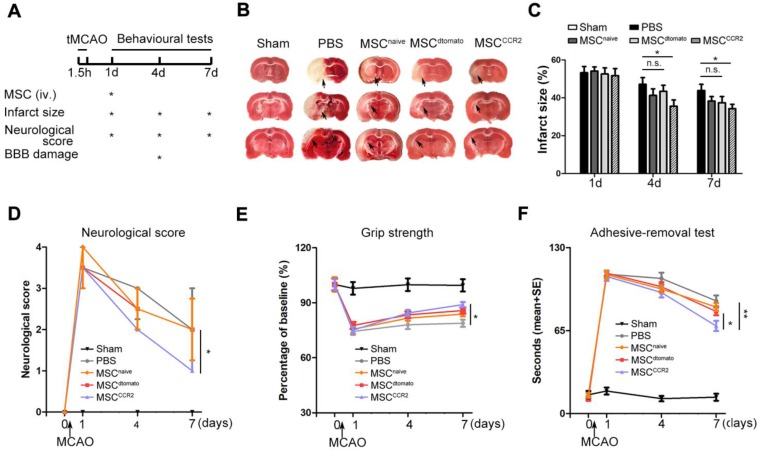

To quantify the therapeutic effects of MSCCCR2 treatment, a series of evaluations assessing the neurological outcomes were performed as shown in Figure 4A. To calculate the infarct size, brain sections of each group were stained with 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC). We observed significant difference in reduced infarct volume between MSCCCR2-treated and PBS-treated rats at day7 following MCAO (Figure 4B-C). Then, overall neurological function was assessed using Menzies score as previously described 32. MSCCCR2 group exhibited better recovery of the neurological deficits compared to MSCdtomato group at day7 post-stroke (Figure 4D). Grip strength was measured to reflect forearm motor function. MSCCCR2 group showed significant enhancement in forearm strength at day7, while MSCdtomato did not (Figure 4E). Sensorimotor deficits were also attenuated by MSCCCR2 engraftment, as demonstrated by adhesive-removal test (Figure 4F). In addition, we also observed the obviously improved long-term (1 month) therapeutic outcomes of MSCCCR2 compared to MSCdtomato (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that MSCCCR2 significantly improve the post-stroke neurological recovery in vivo at both structural and functional levels.

Figure 4.

Transplantation of MSCCCR2 ameliorates ischemic lesion in vivo and enhances neurological functional recovery. (A) Scheme of experimental design and workflow. (B) Representative TTC staining images of the coronal brain sections of sham-operated, PBS-treated, naive MSC-treated, MSCdtomato-treated and MSCCCR2-treated Rats 96h after MCAO. (C) Bar graph showed quantification of infarct volume determined by TTC staining on day 1, day 4 and day 7. n = 7. (D) Neurological deficit scores of different groups at day 1, day 4, and day 7 post-MCAO. n = 8. (E) The adhesive-removal test was performed at day 1, day 4, and day 7 after MCAO. n = 8. (F) Grip-strength test showed enhanced forearm muscle force recovery of MSCCCR2 group compared with MSCdtomato group. n = 12. All data are expressed as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and n.s. is non-significant.

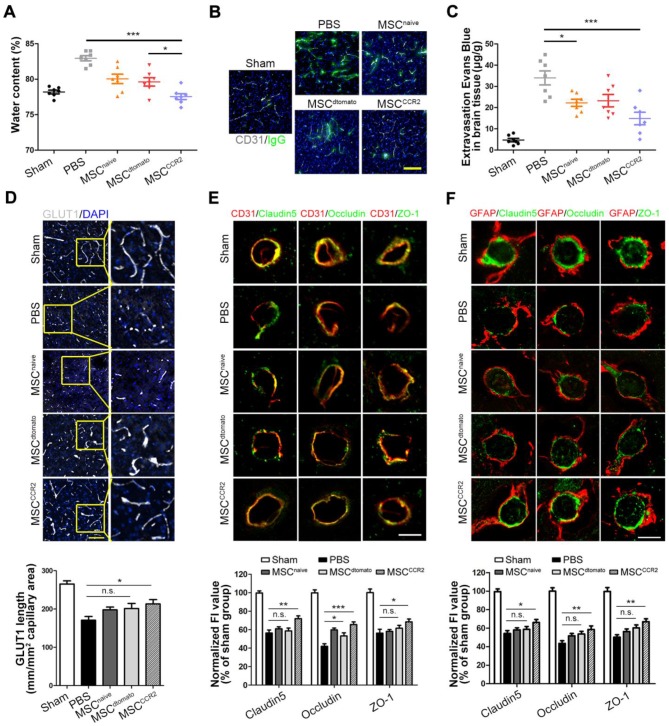

MSCCCR2 promotes neurological recovery through protection of the blood-brain barrier (BBB)

Next, we sought to unveil the underlying mechanism of MSCCCR2-mediated neuroprotection in stroke. Previous evidences suggested that loss of BBB integrity and the resulting brain edema are major factors contributing to poor prognosis, making BBB a rational target for therapeutic interventions 8, 27. In this study, we measured the water content to evaluate the brain edema. Water content reduction in the ipsilateral hemisphere of MSCCCR2 group was found more significant than that of MSCdtomato group at day4 post-MCAO (Figure 5A). Correspondingly, BBB disruption quantified by IgG and EBD extravasation were found attenuated in MSCCCR2-treated stroke rats compared to MSCdtomato-treated controls (Figure 5B-C, Figure S4).

Figure 5.

MSCCCR2 confers protection against blood-brain barrier (BBB) damage. (A) Brain swelling after 4 days of reperfusion. n = 7. (B) Representative confocal microscopy analysis of extravascular IgG (green) deposits in different groups of rats. Scale bar: 200μm. (C) Statistical analysis of Evan's blue intensity by spectrofluorometry showed the reduced BBB leakage after MSCs treatment. n = 7. (D) BBB integrity was detected by immunostaining of anti-GLUT1 (grey). Scale bar: 150μm. For the GLUT1+ microvascular length, we randomly selected six fields in the cortex per animal and three animals per group were measured using the “Neuron J” length analysis tool of Image J (NIH). (E) Co-immunofluorescence staining for CD31 (red) and tight junction marker including Claudin5, Occludin and ZO-1(green) in infarcted brain regions respectively. Scale bar: 25μm. The mean fluorescence intensity (FI) of the tight junction protein expressions normalized to the sham group. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used here for the statistical analysis. (F) Co-immunofluorescence staining for GFAP and Claudin5, for GFAP and Occludin and for GFAP and ZO-1 in infarcted brain regions. Scale bar: 25μm. All data are expressed as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and n.s. is non-significant.

Using in situ immunofluorescence staining, we then detected the BBB structural alterations in vivo. The glucose transporter GLUT1, a marker commonly regarded for BBB formation, was observed with the confocal microscopy 50, 51. The immunoblotting showed the reduced GLUT1+ microvascular length post-stroke was remarkably reversed by MSCCCR2 infusion, while only slight difference was found between the MSCdtomato group and PBS group (Figure 5D). Two factors necessary for the BBB integrity maintenance are continuous endothelial cell layer sealed by TJ and astrocyte endfeet 52, 53. Therefore, we analyzed the expression of TJ proteins (Claudin5, Occludin and ZO-1) in the neurovascular unit (NVU) using double staining with the endothelial marker CD31 or astrocyte marker GFAP. Cross sections of cerebral vessels in the ischemic hemisphere showed disrupted TJ proteins 4 days post-stroke, and MSCdtomato treatment ameliorated the discontinuity slightly. In the contrast, MSCCCR2 engraftment dramatically mitigated TJ proteins degradation and increased CD31 expression in the NVU (Figure 5E-F). As an essential component of NVU, the pericyte density was significantly decreased, while MSCCCR2 administration partially rescued this phenomenon (Figure S5). Compared with MSCdtomato, MSCCCR2 transplantation exhibits an enhances protective role in BBB integrity and endothelial recovery.

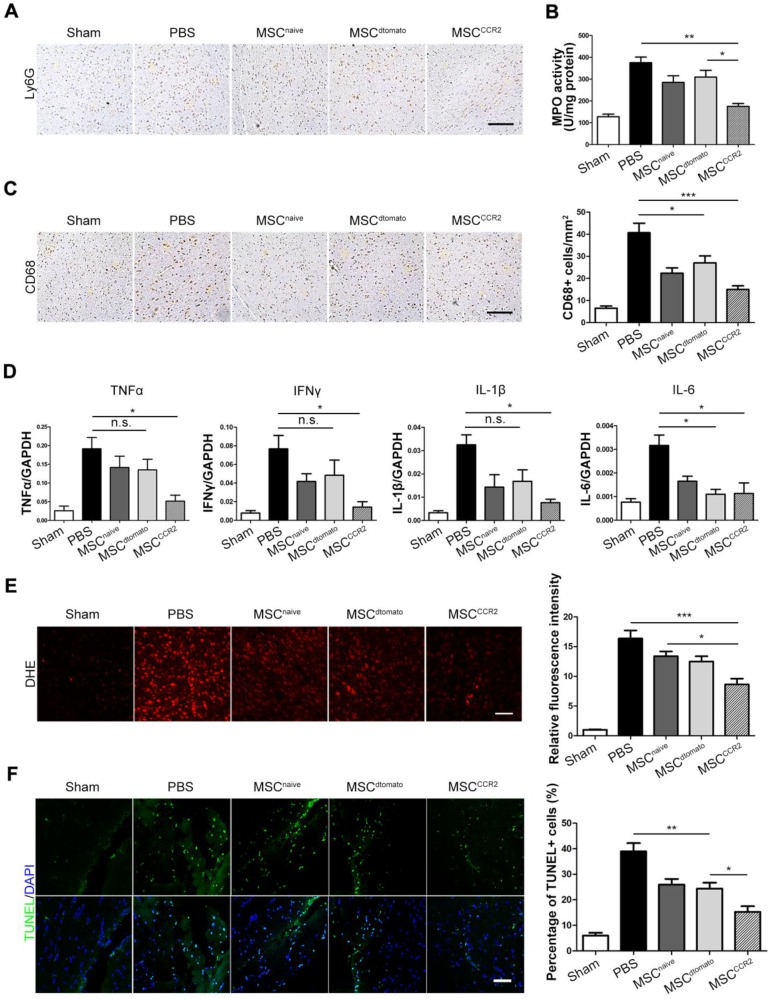

BBB protection alleviates inflammatory infiltration and represses ROS production

The consequent neuroinflammatory response after BBB breakdown is a critical determinant in stroke progression 54, 55. Therefore, we examined neutrophils infiltration in the ischemic hemisphere through anti-Ly6G immunohistochemical staining and quantified neutrophil activity using myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity assays. MSCCCR2 treatment displayed better therapeutic effect on attenuating neutrophils than MSCdtomato 3 days post-injection (Figure 6A-B, Figure S6). CD68+ microglia/macrophages were also counted in the ipsilateral side of each group of rats. The number of CD68+ cells was reduced in MSCCCR2-treated rats, while MSCdtomato group only showed slight difference from PBS group (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

BBB protection alleviates inflammatory infiltration and represses ROS production after ischemic stroke. (A) Ly6G+ neutrophils were identified by immunohistochemistry at 3 days post-injection. Scale bar: 150μm. (B) The level of MPO activity was determined using a chromogenic spectrophotometric method. n = 3. (C) Microglia/macrophage infiltration was detected by CD68 immunohistochemical analysis. Scale bar: 150μm. Six randomized fields were measured, and the experiments were performed in four replicates. (D) The mRNA levels of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β and IL-6 were determined by qRT-PCR. Results are representative of three experiments. (E) Fluorescent staining of brain slices with dihydroethidium (DHE) to detect ROS and DAPI for the nuclei. Right panel shows statistical analysis of DHE-positive cells (/mm2) in brain slices. n = 6. Scale bar: 100μm. (F) Fluorescent staining with DAPI (blue) and TUNEL (green) showed cell apoptosis 3 days after transplantation. Right panel shows the percentage of TUNEL-positive neurons in five independent scopes. Scale bar: 100μm. All data are expressed as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and n.s. is non-significant.

Elevated neutrophil and activated phagocytic system result in massive reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and exacerbate the BBB disruption in turn 56, 57. Then, we evaluated the downstream pro-inflammatory cytokines expression, including TNFα, IFNγ, IL-1β and IL-6, which are typically involved in neuroinflammatory response post-stroke 58, 59. We found notable decrease of these cytokines after MSCCCR2 engraftment; whereas MSCdtomato only slightly reduced their expression versus PBS group (Figure 6D). Furthermore, ROS production was quantified by dihydroethidium (DHE) staining of brain sections. MSCCCR2 treatment was found more antioxidant potency than MSCdtomato (Figure 6E). Since ROS-mediated cell apoptosis is a well-established tissue damage mechanism in stroke model 36, apoptosis levels in the ischemic tissue was determined using the in situ TUNEL staining. Consistent with the DHE staining data, MSCCCR2 were found superior to MSCdtomato in tissue recovery, presumably by targeting BBB (Figure 6F).

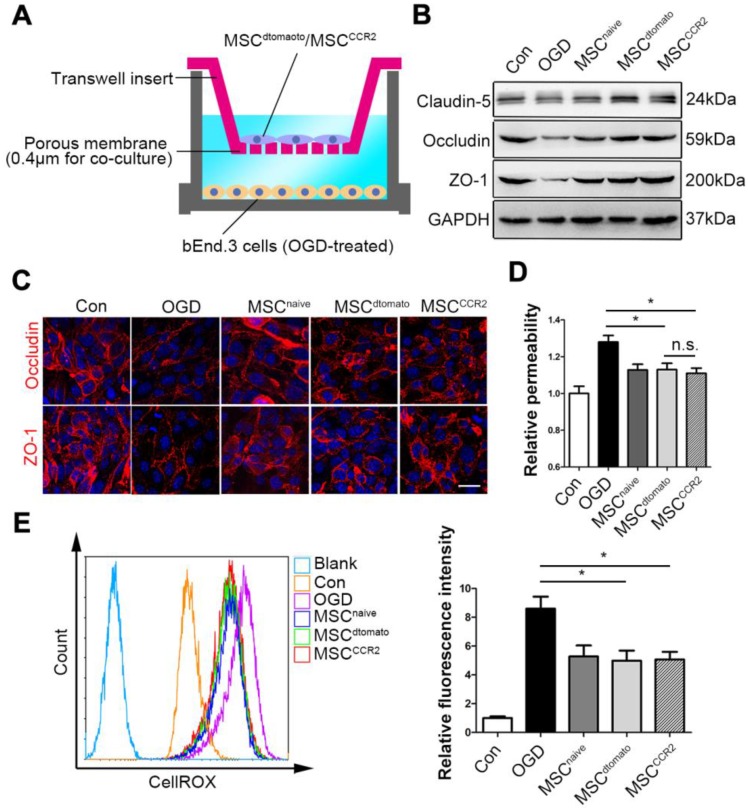

MSCCCR2 prevents the in vitro BBB from OGD-induced ROS generation and tight junction disruption

To verify the effects of MSCCCR2 on BBB protection and investigate them at a mechanistic level, we adopted an in vitro BBB model consisted of a monolayer of mouse brain endothelial cells (bEnd.3 cells), which was exposed to OGD to mimic the in vivo ischemic condition. We firstly confirmed that OGD treatment successfully increase CCL2 and other cytokines expression in brain endothelial cells (Figure S7), indicating this in vitro model worked well. Then, the OGD endothelial BBB were co-cultured with MSCCCR2 or MSCdtomato at a ratio of bEnd.3: MSC=2:1 (Figure 7A). In this co-culture system, MSCCCR2 and MSCdtomato showed similar protective impact on the endothelial preservation, since the short distance between MSCs and endothelial cells eliminated the influence of cell invasive capacity. Both western blotting analysis and immunostaining data demonstrated that co-culture with MSCCCR2/MSCdtomato inhibited OGD-induced TJ proteins degradation and rescued in vitro BBB continuity (Figure 7B-C). Endothelial hyperpermeability and excessive ROS generation result from OGD were also compromised by MSCCCR2/MSCdtomato treatment (Figure 7D-E). These results reconfirm our in vivo findings that MSCCCR2 therapy provides a potent protection against BBB disruption and a soluble factor is potentially involved in the antioxidant mechanism.

Figure 7.

MSCs prevent the in vitro BBB from OGD-induced ROS generation and tight junction disruption. (A) Illustration of the co-culture model of MSCs and in vitro BBB. (B) Representative western blotting images depicted the protein expression of tight junction proteins (Claudin5, Occludin and ZO-1) in OGD-treated bEnd.3 cells after co-culture with MSCs. (C) OGD-treated cells were labeled with anti-Occludin and anti-ZO-1 antibody (red) and analyzed by confocal microscopy to detect the tight junction structure. Scale bar: 20μm. (D) The diffusion of fluorescein sodium across the endothelium monolayer was detected to show the endothelial permeability. n = 5. (E) Density plot analysis of ROS levels in OGD endothelial cells with or without MSC co-culture were measured by flow cytometry. Statistical analysis of intracellular ROS levels showed that MSCs co-culture diminished OGD cells ROS generation. Data were based on three independent experiments. All data are expressed as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 n.s. is non-significant.

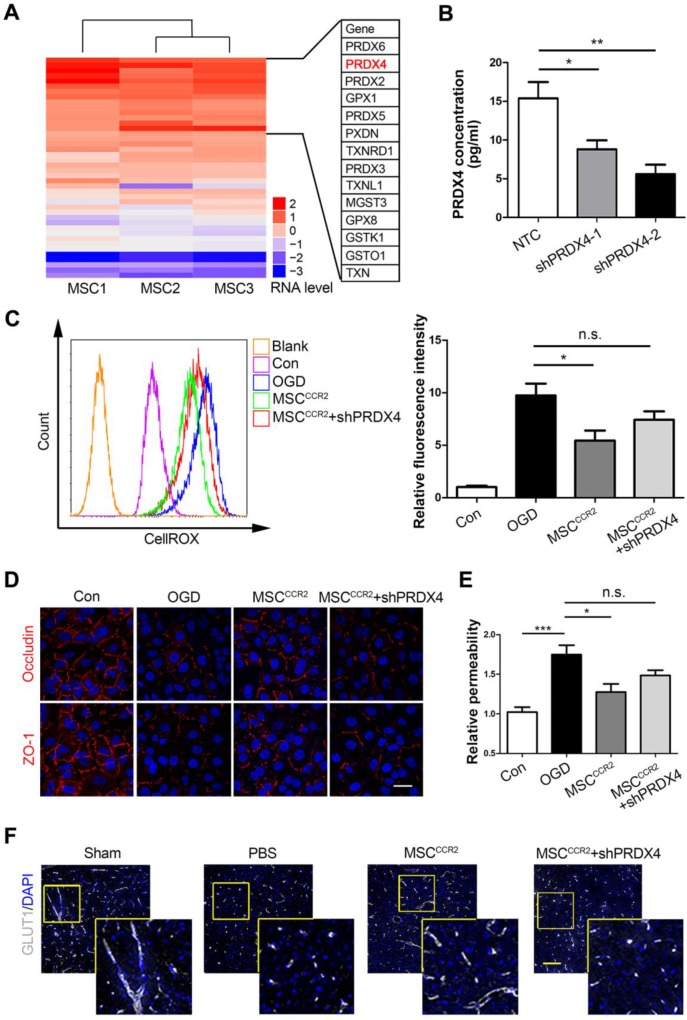

MSCCCR2 restores BBB integrity partially via a PRDX4-mediated antioxidant mechanism

Since pathways thought to initiate BBB disruption including proinflammatory cytokines, neutrophil recruitment and macrophage/microglia activation would converge on the same point, ROS generation 60, 61, we postulated the antioxidant effects of MSC transplantation might play a central role in endothelial preservation. In the previous study, we conducted genome-wide RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of MSCs derived from three different donors, the global transcriptional profiling data of which was deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. SRP095307). To examine the possible redox mechanism of MSCs, a series of antioxidant-related genes were screened through gene ontology (GO) analysis and DAVID gene functional classification tool. As the heat map shown in Figure 8A, the peroxiredoxin (PRDX) family of conserved antioxidant enzymes were highly expressed in MSCs. Since the co-culture data in Figure 7 indicated a potential role of soluble factor, the only known secretory member of the PRDX antioxidant family Peroxiredoxin4 (PRDX4) become a candidate for the redox regulation. Other members like PRDX2 and PRDX5 are located in the cytosol and excluded for the further studies 62, 63. Then, we further confirmed that genetic modification of dtomato or CCR2 did not alter the PRDX4 expression in MSCs (Figure S8). To investigate the potential antioxidant role of PRDX4, we transduced short interfering RNA (shRNA) against PRDX4 (shPRDX4-1 and shPRDX4-2) into the MSCCCR2. Compared to shPRDX4-1, the transfection of shPRDX4-2 reduced PRDX4 expression more efficiently in both mRNA and protein levels (Figure S9). Additionally, the PRDX4 concentration in MSCCCR2 medium was also significantly decreased by shPRDX4-2 treatment (Figure 8B). Then, we used shPRDX4-2 in the following experiments and referred it as shPRDX4 for convenience. ShPRDX4 treatment compromised the antioxidant effects of MSCCCR2 (Figure 8C), and subsequently reversed the in vitro endothelial protection effects (Figure 8D-E). Furthermore, the immunostaining of BBB marker, GLUT1, showed diminished length in the brain slices of MSCCCR2 + shPRDX4 group when compared to MSCCCR2 (Figure 8F, Figure S10A). To quantify the in vivo BBB continuity, the EBD extravasation was also detected increase after shPRDX4 transfection to the MSCCCR2 (Figure S10B). Taken together, the PRDX4-mediated antioxidant pathway might provide new clues for elucidating the potential mechanisms of MSCCCR2 restoring BBB integrity.

Figure 8.

MSCCCR2 restores BBB integrity via a PRDX4-mediated antioxidant mechanism. (A) RNA-seq data analysis of MSCs from three different donors. The heat map displayed genes encoding antioxidant proteins. This heat map was drawn with the RPKM value taking the logarithm of 2. Details of identified high-expressed genes were listed in the right table. (B) ELISA assay showed significant decrease of PRDX4 concentration in culture medium of MSCCCR2 treated with shPRDX4-1 and shPRDX4-2 respectively. n = 3. (C) ShPRDX4 treatment suppressed the antioxidant effects of MSCCCR2. (D) Transfection of shPRDX4 compromised the BBB preservative impacts of MSCCCR2 in vitro. Scale bars: 20μm. (E) The endothelial permeability was assessed by measuring the diffusion of sodium fluorescein. n = 5. (F) Representative immunostaining images of brain slices with BBB marker GLUT1. Scale bars: 75μm. All data are expressed as means ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and n.s. is non-significant.

Discussion

Stroke still causes majority of disability worldwide. Even though tPA treatment and endovascular intervention (EVI) are two widely approved thrombolytic therapies for patients with AIS, the narrow therapeutic window (4.5 h for tPA and 12 h for EVI) limit their clinical application 64, 65. Recent evidences suggest that MSCs transplantation could benefit stroke recovery and extend the therapeutic time window for the patients who miss the safe use of tPA or EVI 18. However, the intravenously injected MSCs typically distribute to the lungs and are detected at only low frequencies in injured tissues. Therefore, the strategies that enhance local recruitment will improve the effectiveness of cellular therapy through acceleration of tissue recovery 66. In the present study, we identified CCL2 as a highly expressed chemokine ligand in the ischemic brain, and thus overexpressed CCR2 in MSCs. We elucidated that these MSCCCR2 cells exhibited enhanced homing capacity to the ischemic hemisphere and notably improved the neurological recovery through BBB protection post-stroke.

Some studies claimed that the stem cell therapy could not only exert neuroprotective effects in the local microenvironment, but also modulate the splenic activation and peripheral immune responses 67, 68. However, it is still widely believed that the therapeutic effects of MSCs depend mainly on cell-to-cell interaction and/or juxtacrine activity, the ideal situation for the MSCs therapy is finding the infused cells recruited to the target lesions or tissue 18, 69, 70. This explains why some preclinical and clinical trials directly inject MSCs into the local lesions 71-73. However, this local administration is unsuitable for the AIS treatment, owing to the potential invasive damages. The intravenous route provides a relatively safe mode, but is lack of the satisfied homing efficiency to target lesions in vivo. Therefore, it is imperative to develop new approach for enhancing MSCs in vivo migration capacity.

The mobilization of infused MSCs needs the fine-tuned interaction between set of chemokine ligands secreted by ischemic tissues and the corresponding chemotactic receptors expressed on the surface of MSCs 24. In this study, we detected the expression of CCL2 peaked at 24 h post-stroke in vivo (Figure 1). In vitro study also confirmed that OGD treatment could increase CCL2 expression in brain endothelial cells (Figure S6). These results were consistent with some previous evidences 27, 28. CCL2 expression was detected within 6 hours post-stroke from different cell types like endothelial cells, astrocytes, neurons and microglia 74, 75. The presence of CCL2 was found highly correlated with post-ischemic inflammatory responses, including transendothelial migration of monocyte/macrophage across the BBB and the subsequent BBB disruption 74, 76, 77. Andres et al. also elucidated the transendothelial migration of intravascularly delivered neural stem cells in MCAO mice were reliant on CCL2/CCR2 interaction after cerebral ischemia 28. Here, we thus overexpressed CCR2 on MSCs via genetic modification. As expected, increased number of MSCCCR2 was observed in the ischemic hemisphere, exerting superior protection for the post-stroke neurological recovery at both structural and functional levels. We further revealed that the possible mechanism underlying these beneficial effects of MSCCCR2 might rely on the focal BBB reservation.

The BBB disruption along with the subsequent inflammatory infiltration is considered as one of the typical hallmarks of reperfusion injury post-stroke 78. Thus, preserving BBB integrity is vital for promoting neurological recovery following cerebral ischemia. Neutrophil migration initiates within 24 h post-stroke followed by monocyte/macrophage migration up to 5 days 79. Meanwhile, proinflammatory mediators including IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, IFNγ and ROS are generated by these inflammatory cells, leading to the endothelial TJ degradation and BBB damage in turn 14. Here, we found MSCCCR2 treatment preserved TJ proteins expression and maintained BBB endothelial structural integrity in MCAO rats (Figure 5D-F), presumably by increasing MSCs engrafted in the ischemic lesions. Moreover, ROS levels were found dramatically reduced in brain sections of MSCCCR2-treated rats using the DHE staining (Figure 6E). The antioxidant potency of MSCCCR2 was also confirmed in OGD-treated endothelial cells after co-culture with MSCs, indicating potential effects of certain soluble factors (Figure 7). The occurrence of oxidative stress is a well-known phenomenon after reperfusion, as well as an emerging therapeutic target 61. Here, we provided an alternative antioxidant candidate for stroke treatment. Using the RNA-seq analysis, we indicated that PRDX4 secreted by recruited MSCs mainly contributed to the antioxidant protection of BBB (Figure 8A). Besides that, previous studies demonstrated that knockout of either CCL2 or its corresponding receptor CCR2 would lead to diminished infarction volume and stabilized TJ complexes 74, 80, 81. Indeed, we also observed the in vitro competitive binding for CCL2 of both MSCCCR2 and CCR2-expressing endothelial cells (data not shown), which might reduce the CCL2/CCR2 interaction in the endothelial cells and consequently protect the BBB integrity. This effect could be another potential mechanism underlying the BBB preservation of MSCCCR2 that deserves further investigation. In sum, this study suggested a multi-target therapeutic role of MSCs in post-stroke redox regulation, BBB maintenance and anti-inflammatory responses.

Taken together, we transduce CCR2 to MSCs and improve their homing capacity to the ischemic hemisphere after the intravenous administration (Figure S11, left panel). Furthermore, we elucidate the adoptive infusion of MSCCCR2 enhances the therapeutic outcomes after stroke through a PRDX4-mediated antioxidant protection of BBB integrity (Figure S11, right panel). Other approaches to improve the therapeutic effects of MSCs like transplantation timing, route, and dosage deserve the further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Stem cell and Translational Research (2018YFA0107203, 2017YFA0103403), Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA16020701), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81425016, 81730005, 31771616, 81671178); the Key Scientific and Technological Projects of Guangdong Province (2014B020226002, 2015B020228001, 2015B020229001, 2016B030230001, and 2017B020231001); the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2014A030310049, S2013030013305, 2017A030310237, 2017A030311013); the Key Scientific and Technological Program of Guangzhou City (201803040011, 201704020223 and 201604020132); Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (GDUPS, 2013), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016M602583, 2017T100657).

Abbreviations

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stromal cells

- AIS

acute ischemic stroke

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- PRDX4

peroxiredoxin4

- OGD

oxygen-glucose deprivation

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

- TJ

tight junction

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- TTC

2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride

- EBD

Evans blue dye

- NVU

neurovascular unit

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- DHE

dihydroethidium

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- GO

Gene Ontology.

References

- 1.Lackland DT, Roccella EJ, Deutsch AF, Fornage M, George MG, Howard G. et al. Factors influencing the decline in stroke mortality: a statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:315–53. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000437068.30550.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caplan LR. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1240–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adeoye O, Hornung R, Khatri P, Kleindorfer D. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator use for ischemic stroke in the United States: a doubling of treatment rates over the course of 5 years. Stroke. 2011;42:1952–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zivin JA. Acute stroke therapy with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) since it was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Ann Neurol. 2009;66:6–10. doi: 10.1002/ana.21750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cramer SC, Stradling D, Brown DM, Carrillo-Nunez IM, Ciabarra A, Cummings M. et al. Organization of a United States county system for comprehensive acute stroke care. Stroke. 2012;43:1089–93. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, Thornton J. et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1019–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell BC, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, Dewey HM, Churilov L, Yassi N. et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1009–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khatri R, McKinney AM, Swenson B, Janardhan V. Blood-brain barrier, reperfusion injury, and hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2012;79:S52–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182697e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haley MJ, Lawrence CB. The blood-brain barrier after stroke: Structural studies and the role of transcytotic vesicles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:456–70. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16629976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obermeier B, Daneman R, Ransohoff RM. Development, maintenance and disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2013;19:1584–96. doi: 10.1038/nm.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haseloff RF, Dithmer S, Winkler L, Wolburg H, Blasig IE. Transmembrane proteins of the tight junctions at the blood-brain barrier: structural and functional aspects. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;38:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Jiang X, Zhang L, Pu H, Hu X, Zhang W. et al. Endothelium-targeted overexpression of heat shock protein 27 ameliorates blood-brain barrier disruption after ischemic brain injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E1243–E52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1621174114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang G, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Lu Y, Wang Y, Huang J. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells maintain blood-brain barrier integrity by inhibiting aquaporin-4 upregulation after cerebral ischemia. Stem Cells. 2014;32:3150–62. doi: 10.1002/stem.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iadecola C, Anrather J. The immunology of stroke: from mechanisms to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:796–808. doi: 10.1038/nm.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moskowitz MA, Lo EH, Iadecola C. The science of stroke: mechanisms in search of treatments. Neuron. 2010;67:181–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boltze J, Lukomska B, Jolkkonen J, consortium M-I. Mesenchymal stromal cells in stroke: improvement of motor recovery or functional compensation? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1420–1. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Li Y, Zhang RL, Cui Y, Chopp M. Bone marrow stromal cells promote skilled motor recovery and enhance contralesional axonal connections after ischemic stroke in adult mice. Stroke. 2011;42:740–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.607226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eckert MA, Vu Q, Xie K, Yu J, Liao W, Cramer SC. et al. Evidence for high translational potential of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy to improve recovery from ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1322–34. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagi H, Soto-Gutierrez A, Parekkadan B, Kitagawa Y, Tompkins RG, Kobayashi N. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: Mechanisms of immunomodulation and homing. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:667–79. doi: 10.3727/096368910X508762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sohni A, Verfaillie CM. Mesenchymal stem cells migration homing and tracking. Stem Cells Int. 2013;2013:130763. doi: 10.1155/2013/130763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gervois P, Wolfs E, Ratajczak J, Dillen Y, Vangansewinkel T, Hilkens P. et al. Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Ischemic Stroke: Preclinical Results and the Potential of Imaging-Assisted Evaluation of Donor Cell Fate and Mechanisms of Brain Regeneration. Med Res Rev. 2016;36:1080–126. doi: 10.1002/med.21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yavagal DR, Lin B, Raval AP, Garza PS, Dong C, Zhao W. et al. Efficacy and dose-dependent safety of intra-arterial delivery of mesenchymal stem cells in a rodent stroke model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93735. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acosta SA, Tajiri N, Hoover J, Kaneko Y, Borlongan CV. Intravenous Bone Marrow Stem Cell Grafts Preferentially Migrate to Spleen and Abrogate Chronic Inflammation in Stroke. Stroke. 2015;46:2616–27. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karp JM, Leng Teo GS. Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:206–16. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sordi V. Mesenchymal stem cell homing capacity. Transplantation. 2009;87:S42–5. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a28533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan YP, Sailor KA, Lang BT, Park SW, Vemuganti R, Dempsey RJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 plays a critical role in neuroblast migration after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1213–24. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mao L, Li P, Zhu W, Cai W, Liu Z, Wang Y. et al. Regulatory T cells ameliorate tissue plasminogen activator-induced brain haemorrhage after stroke. Brain. 2017;140:1914–31. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andres RH, Choi R, Pendharkar AV, Gaeta X, Wang N, Nathan JK. et al. The CCR2/CCL2 interaction mediates the transendothelial recruitment of intravascularly delivered neural stem cells to the ischemic brain. Stroke. 2011;42:2923–31. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rombouts WJ, Ploemacher RE. Primary murine MSC show highly efficient homing to the bone marrow but lose homing ability following culture. Leukemia. 2003;17:160–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wynn RF, Hart CA, Corradi-Perini C, O'Neill L, Evans CA, Wraith JE. et al. A small proportion of mesenchymal stem cells strongly expresses functionally active CXCR4 receptor capable of promoting migration to bone marrow. Blood. 2004;104:2643–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Liu H, Zhang H, Ye Q, Wang J, Yang B. et al. ST2/IL-33-Dependent Microglial Response Limits Acute Ischemic Brain Injury. J Neurosci. 2017;37:4692–704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3233-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menzies SA, Hoff JT, Betz AL. Middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats: a neurological and pathological evaluation of a reproducible model. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:100–6. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199207000-00014. discussion 6-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouet V, Boulouard M, Toutain J, Divoux D, Bernaudin M, Schumann-Bard P. et al. The adhesive removal test: a sensitive method to assess sensorimotor deficits in mice. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1560–4. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bacigaluppi M, Pluchino S, Peruzzotti-Jametti L, Kilic E, Kilic U, Salani G. et al. Delayed post-ischaemic neuroprotection following systemic neural stem cell transplantation involves multiple mechanisms. Brain. 2009;132:2239–51. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang MH, Cai B, Tuo Y, Wang J, Zang ZJ, Tu X. et al. Characterization of Nestin-positive stem Leydig cells as a potential source for the treatment of testicular Leydig cell dysfunction. Cell Res. 2014;24:1466–85. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleinschnitz C, Grund H, Wingler K, Armitage ME, Jones E, Mittal M, Post-stroke inhibition of induced NADPH oxidase type 4 prevents oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. PLoS Biol; 2010. p. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, Li W, Wang Y, Fan W, Li P, Lin W. et al. Islet-1 overexpression in human mesenchymal stem cells promotes vascularization through monocyte chemoattractant protein-3. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1843–54. doi: 10.1002/stem.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng Y, Chen X, Liu Q, Zhang X, Huang K, Liu L. et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells infusions improve refractory chronic graft versus host disease through an increase of CD5+ regulatory B cells producing interleukin 10. Leukemia. 2015;29:636–46. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benchenane K, Berezowski V, Ali C, Fernandez-Monreal M, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Brillault J. et al. Tissue-type plasminogen activator crosses the intact blood-brain barrier by low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-mediated transcytosis. Circulation. 2005;111:2241–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163542.48611.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Z, Wang J, Cai L, Zhong B, Luo H, Hao Y. et al. Role of the stem cell-associated intermediate filament nestin in malignant proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ke Q, Li L, Cai B, Liu C, Yang Y, Gao Y. et al. Connexin 43 is involved in the generation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:2221–33. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perriere N, Demeuse P, Garcia E, Regina A, Debray M, Andreux JP. et al. Puromycin-based purification of rat brain capillary endothelial cell cultures. Effect on the expression of blood-brain barrier-specific properties. J Neurochem. 2005;93:279–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.03020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, Cai J, Huang Y, Ke Q, Wu B, Wang S. et al. Nestin regulates proliferation and invasion of gastrointestinal stromal tumor cells by altering mitochondrial dynamics. Oncogene. 2016;35:3139–50. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qin A, Lai DH, Liu Q, Huang W, Wu YP, Chen X. et al. Guanylate-binding protein 1 (GBP1) contributes to the immunity of human mesenchymal stromal cells against Toxoplasma gondii. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:1365–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619665114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li P, Gan Y, Sun BL, Zhang F, Lu B, Gao Y. et al. Adoptive regulatory T-cell therapy protects against cerebral ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:458–71. doi: 10.1002/ana.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R. et al. Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron. 2010;68:409–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ransohoff RM, Liu L, Cardona AE. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: multipurpose players in neuroinflammation. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;82:187–204. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)82010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mennicken F, Maki R, de Souza EB, Quirion R. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in the CNS: a possible role in neuroinflammation and patterning. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:73–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown CM, Mulcahey TA, Filipek NC, Wise PM. Production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines during neuroinflammation: novel roles for estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4916–25. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chow BW, Gu C. The molecular constituents of the blood-brain barrier. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:598–608. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Winkler EA, Nishida Y, Sagare AP, Rege SV, Bell RD, Perlmutter D. et al. GLUT1 reductions exacerbate Alzheimer's disease vasculo-neuronal dysfunction and degeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:521–30. doi: 10.1038/nn.3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang J, Mancuso MR, Maier C, Liang X, Yuki K, Yang L. et al. Gpr124 is essential for blood-brain barrier integrity in central nervous system disease. Nat Med. 2017;23:450–60. doi: 10.1038/nm.4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chelluboina B, Klopfenstein JD, Pinson DM, Wang DZ, Vemuganti R, Veeravalli KK. Matrix Metalloproteinase-12 Induces Blood-Brain Barrier Damage After Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Stroke. 2015;46:3523–31. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chu HX, Kim HA, Lee S, Moore JP, Chan CT, Vinh A. et al. Immune cell infiltration in malignant middle cerebral artery infarction: comparison with transient cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:450–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McKittrick CM, Lawrence CE, Carswell HV. Mast cells promote blood brain barrier breakdown and neutrophil infiltration in a mouse model of focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2015;35:638–47. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Doll DN, Hu H, Sun J, Lewis SE, Simpkins JW, Ren X. Mitochondrial crisis in cerebrovascular endothelial cells opens the blood-brain barrier. Stroke. 2015;46:1681–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jin M, Kim JH, Jang E, Lee YM, Soo Han H, Woo DK. et al. Lipocalin-2 deficiency attenuates neuroinflammation and brain injury after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1306–14. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shimamura M, Nakagami H, Osako MK, Kurinami H, Koriyama H, Zhengda P. et al. OPG/RANKL/RANK axis is a critical inflammatory signaling system in ischemic brain in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8191–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400544111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin R, Cai J, Kostuk EW, Rosenwasser R, Iacovitti L. Fumarate modulates the immune/inflammatory response and rescues nerve cells and neurological function after stroke in rats. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13:269. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0733-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pun PB, Lu J, Moochhala S. Involvement of ROS in BBB dysfunction. Free radical research. 2009;43:348–64. doi: 10.1080/10715760902751902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kahles T, Luedike P, Endres M, Galla HJ, Steinmetz H, Busse R. et al. NADPH oxidase plays a central role in blood-brain barrier damage in experimental stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:3000–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hofmann B, Hecht HJ, Flohe L. Peroxiredoxins. Biol Chem. 2002;383:347–64. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wood ZA, Schroder E, Robin Harris J, Poole LB. Structure, mechanism and regulation of peroxiredoxins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mulder MJ, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Dippel DW, Investigators MC. Letter by Mulder et al Regarding Article, "2015 AHA/ASA Focused Update of the 2013 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Regarding Endovascular Treatment: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association". Stroke. 2015;46:e235. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP, Biller J, Coffey CS, Hoh BL, Jauch EC. et al. 2015 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Focused Update of the 2013 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Regarding Endovascular Treatment: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46:3020–35. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang X, Huang W, Chen X, Lian Y, Wang J, Cai C. et al. CXCR5-Overexpressing Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Exhibit Enhanced Homing and Can Decrease Contact Hypersensitivity. Mol Ther. 2017;25:1434–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yang B, Hamilton JA, Valenzuela KS, Bogaerts A, Xi X, Aronowski J. et al. Multipotent Adult Progenitor Cells Enhance Recovery After Stroke by Modulating the Immune Response from the Spleen. Stem Cells. 2017;35:1290–302. doi: 10.1002/stem.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schreiber S, Bueche CZ, Garz C, Kropf S, Angenstein F, Goldschmidt J. et al. The pathologic cascade of cerebrovascular lesions in SHRSP: is erythrocyte accumulation an early phase? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:278–90. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, Jiang Y, Jiang X, Guo X, Ning H, Li Y. et al. CCR7 guides migration of mesenchymal stem cell to secondary lymphoid organs: a novel approach to separate GvHD from GvL effect. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1890–903. doi: 10.1002/stem.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Borlongan CV, Glover LE, Tajiri N, Kaneko Y, Freeman TB. The great migration of bone marrow-derived stem cells toward the ischemic brain: therapeutic implications for stroke and other neurological disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95:213–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, Shou M, Lee CW, Barr S. et al. Local delivery of marrow-derived stromal cells augments collateral perfusion through paracrine mechanisms. Circulation. 2004;109:1543–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124062.31102.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ciccocioppo R, Bernardo ME, Sgarella A, Maccario R, Avanzini MA, Ubezio C. et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of fistulising Crohn's disease. Gut. 2011;60:788–98. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.214841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Molendijk I, Bonsing BA, Roelofs H, Peeters KC, Wasser MN, Dijkstra G. et al. Allogeneic Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Promote Healing of Refractory Perianal Fistulas in Patients With Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:918–27. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.014. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dimitrijevic OB, Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV. Effects of the chemokine CCL2 on blood-brain barrier permeability during ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:797–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Che X, Ye W, Panga L, Wu DC, Yang GY. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expressed in neurons and astrocytes during focal ischemia in mice. Brain Res. 2001;902:171–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Roberts TK, Eugenin EA, Lopez L, Romero IA, Weksler BB, Couraud PO. et al. CCL2 disrupts the adherens junction: implications for neuroinflammation. Lab Invest. 2012;92:1213–33. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mahad D, Callahan MK, Williams KA, Ubogu EE, Kivisakk P, Tucky B. et al. Modulating CCR2 and CCL2 at the blood-brain barrier: relevance for multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. Brain. 2006;129:212–23. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Candelario-Jalil E. Injury and repair mechanisms in ischemic stroke: considerations for the development of novel neurotherapeutics. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:644–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kriz J, Lalancette-Hebert M. Inflammation, plasticity and real-time imaging after cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:497–509. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0496-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strecker JK, Minnerup J, Schutte-Nutgen K, Gess B, Schabitz WR, Schilling M. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1-deficiency results in altered blood-brain barrier breakdown after experimental stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:2536–44. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dimitrijevic OB, Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV. Absence of the chemokine receptor CCR2 protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Stroke. 2007;38:1345–53. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259709.16654.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.